Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

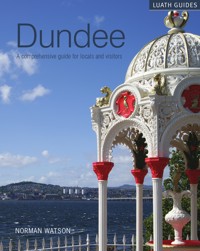

Where can you find five castles, an Antarctic research ship and award winning modern art and theatre venues side by side? Which Scottish city made its name producing the 'three Js' of jute, jam and journalism, was home to a higher population of working women than anywhere else in the UK in the late 19th century and gave us the world's worst poet? In this first ever comprehensive guide to the city join author Norman Watson on a journey street-by-street through Dundee, UNESCO City of Design, shortlisted City of Culture, and now proudly selected to host the world-beating V&A Museum. Explore key streets and buildings and meet famous Dundee residents, recalling stories of the city's past as a manufacturing monolith and looking to its bright future as a hub of learning and culture. Fully illustrated and featuring full colour maps, this guide to Dundee is the perfect companion for locals and visitors alike.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 256

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

DR NORMAN WATSON was a journalist with The Courier in Dundee for 25 years and wrote more than 5,000 news features for the paper. He remains a Courier columnist and is now publishing giant DC Thomson’s first ever company historian.

An award-winning author, his books include the best-selling Dundee: A Short History (2006), The Biography of William McGonagall (2010) and the internationally-acclaimed Dundee Dicshunury (2012).

As a historian Norman Watson has co-curated major exhibitions in Dundee, London and Edinburgh and in 2006 was invited to open the Scottish Parliament’s first-ever public exhibition.

In this fascinating eyewitness account of Dundee he traces its voyage of discovery from manufacturing monolith to a city as comfortable with the creative industries and life sciences as it was with jute, jam and journalism.

First published 2015

ISBN: 978-1-910324-66-0

All images by Norman Watson except where otherwise stated

Typeset in 8.5 point Sabon by

3btype.com

The author’s right to be identified as author of this work under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

© Norman Watson 2015

Contents

Map 1: Dundee City Centre

Map 2: Dunee and its Surroundings Areas

Acknowledgements

Foreword – Lord Provost Bob Duncan

Introduction

CHAPTER ONE The High Street

CHAPTER TWO Nethergate and Overgate

CHAPTER THREE Ward Road and Surrounds

CHAPTER FOUR The Central Waterfront

CHAPTER FIVE The Law

CHAPTER SIX Cowgate and Routes North-East

CHAPTER SEVEN West Port and Hawkhill

CHAPTER EIGHT Perth Road

CHAPTER NINE Ferries and Bridges

CHAPTER TEN Historic Suburbs

CHAPTER ELEVEN The Kingsway

CHAPTER TWELVE Eastern Dundee

CHAPTER THIRTEEN Museums and Galleries

CHAPTER FOURTEEN Parks and Gardens

CHAPTER FIFTEEN Sport in Dundee

CHAPTER SIXTEEN Dundee’s Castles

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

I would firstly and particularly like to thank Lord Provost Bob Duncan for kindly agreeing to write a foreword for this guide. He has been a tremendous ambassador for the city during his distinguished term of office.

I am indebted as always to the professional librarians, curators and archivists in Dundee for their help with this work and their support over many years. Among them, my friends Iain Flett of Dundee City Archives, Eileen Moran, Deirdre Sweeney, Carol Smith and Maureen Reid of Dundee Central Libraries and Rhona Rodger, formerly of The McManus Galleries, now with Perth Museum & Galleries.

I wish to offer my sincere thanks to Katrin Purps for her assistance. Katrin, from Berlin, was unstintingly helpful with advice on photography. In that respect thanks are also due to my brother John Watson, for playfully telling me off about my woeful camera skills and pointing me in the proper direction, such as holding the camera the right way up and facing the subject.

I am indebted to DC Thomson & Co for their help – especially Mr Murray Thomson – and to Catherine Cooper, formerly of that company, who was a splendid ally in combating administrative hiccups. My knowledgeable friend Stuart McFarlane bravely faced down my incessant questions on technological matters while Michael Freist kindly dipped into his mill memories on my behalf.

I am grateful to Muriel Duffy, warden, and the residents of Powrie Place Sheltered Housing Complex for their kindness. They returned the brazenness of my unsolicited visit with warmth and understanding.

My thanks, of course, go to my fellow Dundee historians and authors. We all try to move things on in our own way, but this necessarily requires a gentle synthesis of past works, my own included!

Foreword

by Lord Provost Bob Duncan

I AM VERY PROUD to say that I have lived my entire life in Dundee. I have seen the city undergo some magnificent changes and triumph out of hardship and negativity. When I was younger, Dundee was a city famous for its jam, jute and journalism. Many of my school friends went to work in one of the many mills, or to help make Keiller’s jam or delivering the news at DC Thomson’s.

I chose to go down the path of the creative industries, gaining an apprenticeship at the greeting card and postcard printers, Valentines. Dundee always had an international outlook and the global economy meant we had to move on – which allowed me to watch the city rise and develop into a thriving modern creative and educational hub.

Today’s Dundee is diverse, innovative and spirited. I am honoured to represent the city at this exciting time. We are now home to a cutting-edge life sciences research sector, a dynamic digital media industry and a vibrant arts and cultural scene. It is also one of only 16 cities on the planet to be named UNESCO City of Design, putting us on par with places like Montreal, Berlin and Helsinki. Whether it’s the fantastic quality of life on offer, the innovation and excellence demonstrated by the science and technology sectors, or the city’s thriving and eclectic music scene, there’s still much more to discover about Dundee.

So, like all successful communities, Dundee is constantly in transition. There is the £1billion project that will link the city centre with the waterfront setting, which includes an international centre of design excellence backed by the world famous Victoria and Albert Museum, to be known as the V&A Dundee. These changes will boost the economy and cement Dundee’s reputation with visitors from across the globe.

This book illustrates, elaborates and explains Dundee’s past and present. Read on to see how far we have come, and the exciting path we are travelling. Join us on the journey.

Lord Provost Bob Duncan City of Dundee

Lord Provost Bob Duncan, City of Dundee

Introduction

The City Churches.

MAP 1 ▪ F4

DUNDEE CELEBRATES ITS 825th birthday in 2015. It does so in ebullient good spirits as a UK City of Culture 2017 finalist, a proud UNESCO City of Design and excited host to the world-beating V&A Museum.

This guide is a celebration of this amazing city, anchored to its glorious south-facing estuarial location, seven miles from the sea, and brooded over by the rounded extinct volcano known as the Law.

Two paintings by Gregory Lange in the City Chambers set the scene for this Guide. They portray notable personalities in the history of Dundee and the city’s principal industries of jute, flax, shipbuilding and whaling.

It explores and explains the streets, buildings, trades, customs, traditions – and people – that have contributed to the city’s progress from the earliest settlement to the present day.

It offers a much-needed eyewitness account of the changes that have taken place: Dundee’s voyage of discovery from manufacturing monolith to a flexible, modern university city as comfortable today with research, discovery and learning as it once was with the ‘Three Js’ of jute, jam and journalism.

It shines a spotlight on the rich tapestry of social, political and cultural reforms, technological advances, ceremonies, festivals and special events that define and shape today’s city of 150,000 people, Scotland’s fourth largest.

In doing so it sprinkles across its easily-read chapters a rounded, authoritative account of the city’s remarkable history, while offering a new life and times of Dundee that is as much about the city’s present as the past.

The chapters will show that Dundee established itself through enterprise and energy. It built its harbours and docks and harnessed the waters of the River Tay. It pioneered trading routes to the Baltic and established the greatest whaling fleet in the Empire. Its heroic manufacturing output made Dundee the second city in Scotland and a world centre of textiles production. It outstripped Hull as the major importer of flax and overtook Leeds as Britain’s biggest producer of linen on the way to becoming the jute capital of the world – Juteopolis.

Its legacy remains – stunning mill architecture and gifts such as the Caird Hall, the McManus Galleries and the city’s parks.

Post-textiles, Dundee’s energies bent towards a brave new world of electronics. The incoming industries were to revolutionise where Dundonians worked and lived. There was the largest dry battery plant in Europe, Britain’s biggest supplier of watches, the largest single factory in Scotland, a firm that contributed to the development of Concorde, another which produced the first home computers – and one voted ‘The Best Factory in Britain’.

New housing smashed through ancient boundaries and suburbs were created. Vast swathes of the old Dundee were cleared away, transforming the physical appearance of the city. Sprawling estates soon peppered its periphery around Britain’s first ring-road, the idea of visionary city architect James Thomson, one of many Dundonians celebrated in this work.

Dundee waterfront from Newport.

MAP 2 ▪ G2

Dundee also survived the trauma of a fallen rail bridge, built another and opened a road crossing to Fife. It has returned Captain Scott’s Discovery to her home port to become not only an icon of Dundee’s pioneering past, but a totem of the city’s future dynamism. The brilliant branding of Dundee as the ‘City of Discovery’ acted as the impetus for the refurbishment which changed the face of the city. Discovery Point is just one of a multifarious museum provision that boasts two five-star attractions and a former European Museum of the Year. In addition, today’s waterfront is at the heart of an amazing £1 billion, 30-year transformation. The huge project will reconnect the city with its river and be crowned by the £81 million V&A, the world’s greatest museum of art and design.

The murraygate, looking east.

MAP 1 ▪ G7

Dundee has also become a two-university city with a medical school of world repute. It has more students per head of population than any other Scottish city, and of the total UK clinical medicine budget, the city receives more funding than Oxford or Cambridge. So, once a close-knit community of toiling workers amid lavish, swaggering mills, today Dundee is a world-class citadel of science with a global reputation for research, a leader in life and medical sciences, biotechnology, digital media, art and design – and alive with its vast student population day and night.

Its commercial centre has been reinvigorated by the stunning success of the Overgate Centre, ably supported at the other end of town by the Wellgate shopping centre, City Quay and the Gallagher Retail Park.

So Dundee has undergone a period of reinvention, increasing confidence and discovery. And as we move through the 21st century, its civic heart is beating strongly – its proud people with an unshakeable sense of belonging.

Norman Watson October 2015

CHAPTER ONE

The High Street

THE HIGH STREET is the hub of Dundee’s civic, social and commercial life.

From it radiate seven principal streets and the city’s busiest shopping centre; close to it buses and taxis convey passengers to and from all parts of the city; the railway station is within easy reach and there are few of the necessities or luxuries of life – a good mobile signal included – which cannot be obtained in its locality. Yet this High Street is barely 400 metres long from tip to toe.

Early parish church

As archaeology discovers and explains more, excavations suggest occupancy here as early as the 1100s. From a mention in a 13th-century charter and its prominence on the earliest known Dundee seal it seems the young settlement had a parish church dedicated to St Clement, the martyred patron saint of sailors. An ancient church of that name was later recorded on the south side of the High Street, where Hector Boece recalled in 1527, ‘the greater part of the town’s people resorted… where they worshipped the Saint with holy prayers’. There are mentions of St Clement’s being dismantled after the Reformation. By then it had ceased to function as a church following its destruction a decade earlier by the English army of Henry VIII.

The High Street, looking west.

MAP 1 ▪ G5

The old Town House, with its ‘pillars’.

The High Street in the 18th century.

Adam Town House

For two centuries this pivotal point of old Dundee was dominated by the Town House built in 1732 by Scotland’s greatest architect, William Adam. It was one of the finest municipal buildings in Scotland, but also acted as a showy statement by an ambitious mercantile burgh.

Constructed on the site of the city’s Old Tolbooth of 1562, the Adam Town House had seven arched openings with square pillars. At ground level, these arcades enclosed shops and recreated the luckenbooth style of a century earlier, as well as giving the building its local name, ‘The Pillars’.

The Council Chambers occupied the huge first floor of the Town House. The level below the 140ft steeple and four-dial clock contained the female prisoners’ quarters and, ‘In the evenings they could get a glimpse of the sun, and often held conversations with friends on the street.’ Debtors – the cheats and fraudsters – occupied the flat below and common criminals were shoved into the dark and miserable basement. Hangings took place outside.

The Town House was the High Street’s first decent building and it did not take it long to leave its mark on history. In 1745 it was commandeered by Jacobites attempting a return to power. In 1773 its roof was set on fire by prisoners trying to escape. In the 1790s its heavy wooden doors were barred to French Revolutionary protesters. In 1803 the Provost mustered the Dundee Volunteers before it as Napoleon threatened invasion. Then, in 1832, rioters set it on fire to ‘burn out the Tories’.

Debate over demolition

It was also in this great building, in 1788, that Dundee’s first recorded bank raid took place. The Dundee Banking Company was entered from the floor above and £423 was stolen. Two men were executed in Edinburgh for the theft, but it is believed the real culprit escaped after an ‘inside job’.

Stand between Boots and H Samuel’s, look towards the Caird Hall, and just 80 years ago the Town House would have been in your face. Yet it barely survived into the 20th century. When proposals were mooted in the 1920s to create a civic square in front of Dundee’s new Caird Hall, The Courier weighed up the city’s dilemma:

Is the Town House to remain as a monument to one of Scotland’s greatest architects, a centre around which the sentiments of Dundee citizens for generations have gathered; or is it to be wholly demolished, or transplanted stone by stone so that an unobstructed view may be afforded from High Street to the frontal of the new Caird Hall?

The Courier’s question hinted at architect James Thomson’s compromise whereby William Adam’s local masterpiece would be taken down and rebuilt at the west end of the High Street, close to the old Overgate. Other sites suggested were Dock Street and one of the parks. But as the Depression took hold and unemployment in Dundee soared to the record high of 30,000, the decision was taken, in 1931, to demolish the building to provide work for the city’s jobless.

So in the bat of an eye, in 1932, the Town House was removed to enable the creation of City Square, leaving it to be remembered and imagined today by scaled-down models at The Pillars public house in Crichton Street and above the clock at jeweller’s Robertson & Watt in the High Street. A bronze plaque depicts the building outside 21 City Square and the old Town House has the honour of being one of three bronze replicas representing the best of bygone Dundee on plinths fronting the Overgate Centre. But to ordinary Dundonians at home or abroad no building, not even the Old Steeple, typified ‘home’ as much as the Town House – and sparked memories of sweethearts cosily sheltered under its famous ‘Pillars’.

The Caird Hall from City Square – its columned north perspective was paid for by Sir James Caird’s sister Mrs Marryat.

MAP 1 ▪ G4

City Square looking north towards the Overgate Centre and Reform Street.

MAP 1 ▪ G4–G5

The demolition cleared away several historic sites, among them the medieval St Clement’s Well, which stood on the ground now taken up by the square. The town’s sailors once filled their casks at the well of Dundee’s patron saint.

Sir William Wallace and Alexander Scrymgeour at the siege of Dundee Castle in 1297, portrayed in a stained-glass window by Alex Russell at the City Chambers.

Relics survive

Some relics from the 1732 building also survive. Stained glass windows, drawn by Sir Edward Burne-Jones and created by William Morris – two of England’s greatest Pre-Raphaelite artists – are now sublimely backlit at The McManus Galleries. Burne-Jones’ sketches of Sir William Wallace for one of the windows are with Birmingham Art Gallery and there are other examples of his work in Dundee’s City Churches and the Broughty Ferry churches. Two griffin staircase bannister stops and a cut-glass chandelier, both in the City Chambers, are thought also to come from the Town House. Elsewhere, it is said some of the building’s interior wood panelling – ‘complete with umpteen coats of varnish’ – went to Dundee Football Club’s boardroom at Dens Park.

City Square.

MAP 1 ▪ G4–G5

City Square

City Square was opened in 1924 and completed over several years afterwards. It is home to the mahogany-panelled, marbled City Chambers and some council departments, including the Lord Provost’s office, councillors’ lounge and committee rooms. Stained glass here comes from two of Dundee’s twin towns; Orleans in France and Wurzburg in Germany. A visitor information board is located in the square and city ambassadors, in hi-vis, postbox-red jackets, are happy to field enquiries.

Approaching its centenary, the square remains a popular public oasis and hosts many events. In 2014 alone thousands packed it for a visit of the Edinburgh Tattoo, coverage of the Commonwealth Games, the Armed Forces Day parade, the BBC’s World War One on Tour, several university graduations and the international Dare to be Digital Festival.

Within the council presence on its west wing is Dundee City Archives, where local records stretching back 1,000 years are held. Material kept here includes records of Dundee from 1290 and the Robert the Bruce charter of 1327 elevating Dundee to the status of royal burgh. The archives benefit from the efforts of the Friends of City Archives, the first group of its kind in Scotland when it started in 1989. The Friends assist the main archives department by indexing many of the historical documents in storage.

A memorial from the Polish Army outside the City Chambers.

MAP 1 ▪ G4

Caird Hall

City Square is dominated by the pillared northern façade of the Caird Hall – once used by the BBC to depict the Kremlin in the Cold War!

One of the world’s largest emeralds was pressed by King George V in 1914 to make the electrical connection which remotely laid the foundation stone for the hall. The jewel belonged to Dundee’s greatest philanthropist, Sir James Caird (see panel), who proposed and paid for the new hall, subsequently opened in 1923 by the King’s son Edward, later Edward VIII. The emerald is thought to be the second largest ever discovered and now forms a rather unique centrepiece in the Lord Provost’s chain of office. The history of the gem is unknown.

Sir James Caird

Sir James Caird (1837–1916) sprinkled his massive fortune on charitable causes across his native city and beyond. Most famous for the £100,000 (today about £7million) he sunk into the huge hall that bears his name, Caird reached for his chequebook time and time again.

The greying, bearded jute baron built a cancer hospital, a women’s hospital, acquired rare Egyptian relics for Dundee Museum, bought Caird Park and the Caird Rest Home for the city, and left money after his death in 1916 for the town to buy Camperdown Park.

He sent Shackleton on his way to the Antarctic with a sum equivalent to £1.7 million, built an insect house at London Zoo and provided ambulances for the Balkan wars. If his sister could not equal his showy paternalism, her generosity matched his own. Gifts during Mrs Emma Grace Marryat’s lifetime included £10,000 to clear Dundee Royal Infirmary’s debts, £55,000 to purchase Belmont Castle at Meigle for the city and £75,000 to finish and equip the Caird and Marryat Halls. The Caird bequests amounted to over £1million, worth today about £100 million, and ensured the family name immortality in its native city.

Famous names in Dundee

The new Caird Hall could accommodate an audience of 3,300, making it one of the largest public auditoriums in Britain. To a gamut of boos, cheers and ’60s screams, it welcomed Winston Churchill, Bob Hope, Gracie Fields, Frank Sinatra, Mario Lanza, Cliff Richard, The Beatles, Led Zeppelin, The Rolling Stones and the Dalai Lama. It was converted to a cinema during the Second World War and Gone with the Wind played to full houses there for four weeks in 1941.

Caird Hall has recently reintroduced wrestling to its repertoire, rekindling memories of local hero George Kidd, who, after beginning his wrestling career in the late ’40s, dominated the lightweight championship for 26 years and thrilled Caird Hall audiences for as long. Kidd had over 1,000 bouts and only seven defeats. Raising the Caird Hall roof time after time, he retired undefeated as world champion at the age of 51, after defending his title on 49 occasions.

Glittering with comparable distinction among the hall’s firmament of stars is an immense Harrison & Harrison organ, one of the finest concert instruments in Britain. The organ gave its inaugural recital in June 1923 and was formally opened by the Prince of Wales the same year. Describing the visit, The Dundee Advertiser commented:

A touch of comedy which gently tickled the Prince was provided by an old woman. Grasping the young Prince by the arm, she exclaimed, ‘Eh, laddie, are ye no’ thinking of takin’ a wife?’

The small matter of matrimony later led the prince, then Edward VIII, to abdicate.

Events at the hall and its Louis XV-style Marryat Hall subsidiary can be viewed at the Box Office, 16 City Square, or on Dundee City Council’s easily navigable website.

With the Town House removed to make way for the square, Samuel’s Corner, on the junction of High Street and Reform Street, was adopted as Dundee’s time-honoured’ meeting place. ‘See you under Samuel’s clock’ was the promise!

New Inn Entry

New Inn Entry, a pend close to Samuel’s, was once home to many lawyers and Dundee’s first theatre, prior to its move to Yeaman Shore in 1800. The Post Office was also situated here in the early 1800s and The Courier was printed at New Inn Entry for about 11 years from 1861 – the year it became Britain’s cheapest daily newspaper. Jewellers Robertson & Watt at 73 High Street have been selling rings and watches on or near this site since 1841.

New Inn Entry leads to the Forum Centre, a maze of retail units constructed on the site of the former Keiller’s confectionary factory. Its High Street entrance opens into a cobbled courtyard. On the right, the Arctic Bar is a traditional tartan-carpeted Dundee pub with exceptional whaling photographs decorating its walls.

Samuel’s Corner.

MAP 1 ▪ H5

Gardyne’s Land

Close to Desperate Dan’s chest-bursting statue and behind the 18th-century frontage of 71 High Street, Gardyne’s Land is a timeless late-medieval group of linked buildings – possibly merchant homes – restored to provide backpackers’ hostel accommodation. Although constructed around 1600, finds of high-status imported pottery from the 12th to the 14th centuries hint at occupancy at the earliest period of the burgh. Excavations also revealed a 13th-century well, while surviving structural timbers were dated by dendrochronology to 1593. Details of the building’s restoration are displayed in the hostel office.

Gardyne’s Land, off High Street.

MAP 1 ▪ G5

Dundee’s most popular sculpture – Desperate Dan and pals.

Tony Morrow’s fiery dragon.

The memorial clock dedicated to Dundee’s mill girls.

There are three sculptures in this section of High Street. As well as Dan and his comic pals Minnie and Gnasher, who playfully represent the city’s links to publisher DC Thomson, the street is home to Tony Morrow’s dragon and a commemorative clock dedicated to the mill poet Mary Brooksbank (see panel).

The 11ft copper dragon, unveiled in 2003, draws on the legend of the chimeric monster slain after killing nine Dundee maidens. The clock is a timely memorial to female textile workers who once numbered 35,000 in the city. Aptly, it draws upon words from Brooksbank’s eponymous ‘Jute Mill Song’:

The former Clydesdale Bank building in the High Street.

MAP 1 ▪ G5

Oh dear me, the mill’s gaen fest, The puir wee shifters canna get a rest, Shiftin’ bobbins coorse and fine, They fairly mak’ ye work for your ten and nine.

Just to the east, the former Clydesdale Bank building at the High Street– Commercial Street junction is now part of the Optical Express chain.

Medieval meat market

The story of this site portrays the development and transformation of the city since medieval times. In 1561 a flesh market was erected here using stones from the demolished Franciscan monastery in the Howff. It was where ‘horses neighed, galloped, trotted and kicked, and the aged, the women and children were wholly at their mercy.’ In 1776 this meat market was demolished and a new Trades Hall was built in its place, following the Adam Town House in style. Its opening in 1778 was marked by a grand parade of Dundee trades. The shoemaker craft, or cordiners, created a 14-metre-long panoramic frieze on plaster of their part of the pageant. This unique and curious artwork, showing the cordiners accompanying their King Crispin in procession, is a treasured exhibit at The McManus.

Mary Brooksbank

The slender memorial clock in the High Street, opposite Castle Street, bears the words of a poem made famous by the Dundee mill poet Mary Brooksbank.

Brooksbank (1897–1978) was a three-time jailed political spitfire who became a gentle mill poet and one of the world’s first protest singers. One of a family of ten in a two-roomed house, she recalled being kept from school to look after her younger siblings, even though her father was idle. By age 11 she was boosting family finances as an underage shifter of bobbins in the Baltic Mill in Annfield Road. Her first political role was providing tea to striking dockers in a violent dispute in 1911. With local unemployment reaching 30,000 in 1931 she took to the streets as a Communist Party recruit, incited a riot and was rewarded with three months in Perth Prison.

Brooksbank’s secret writing only became public after she had retired, aged 50, to look after her invalid mother. She eventually published a collection of poems, Sidlaw Breezes, in 1966 when she was 68. Nae Sae Lang Syne, her autobiography, and a much rarer work, was completed when she was 75. Her most famous lines were written while she was in prison and are now etched around the mill lassies’ memorial clock. She is also remembered at the community library in Pitairlie Road, which is named in her honour.

Mary Brooksbank.

Stained glass in St Paul’s Cathedral.

MAP 1 ▪ H5

Admiral Duncan.

In turn, the Trades Hall gave way a century later to the triangular Clydesdale Bank building. This survives in the High Street opposite Castle Street, its alcoved women warriors topped by trident-totting Britannia, the female personification of Great Britain.

St Paul’s Cathedral

Close by, the graceful spire of St Paul’s Cathedral of the Episcopal Diocese of Brechin towers 65 metres over the High Street. The cathedral was built in 1853 by Sir George Gilbert Scott, the English Gothic-revival architect who also designed St Pancras Station and The McManus. It is regrettable that this lovely Victorian church, clinging to the ancient castle rock, is smothered by its surroundings.

On this high point of the city centre once stood Dundee’s castle, or ancient fortress. The 18th-century Castle Hill House, on the corner at 1 High Street, is said to incorporate remnants of the old fortification in its medieval underbuilding. Near it, apocryphally, the young Scottish patriot William Wallace slew the English garrison governor’s son, and so struck the first blow for Scottish independence.

Birthplace of Admiral Duncan

Steeped in history, this site was also once home to a house visited by the Chevalier James Stuart during the 1715 rebellion. Dundee was the largest Scottish town to declare for the ‘Old Pretender’ (it ‘swapped ends’ and swore allegiance to George II in 1745). The property was subsequently used by Alexander Duncan of Lundie, and here his war hero son Adam Duncan was born in 1731.

On a plinth before the cathedral stands a portrayal in bronze of Duncan, victor of the Battle of Camperdown in 1797. The admiral is seen in a nautical pose, holding a telescope in a sculpture by Janet Scrymgeour Wedderburn (see panel).

Household-name stores

At one time a trio of locally famous family stores dominated corner sites at the High Street–Commercial Street–Murraygate crossroads. The Neoclassical frontage on the northwest corner was constructed in 1906–1908 to house Dundee’s most iconic department store, DM Brown. This elegant draper’s became Edwardian Dundee’s Harrods. It boasted an ‘indoor street’ arcade and a pillared tearoom featuring carved Italian marble and the largest sheet of curved glass ever manufactured. The story goes that DM Brown, having acquired a Commercial Street frontage in addition to his premises in High Street, wanted to join the two by ‘turning the corner’. He was frustrated by a chemist who demanded an exorbitant price for his corner stance. Brown’s answer was to make a continuous row of display windows – the indoor arcade – all under cover and running behind the chemist’s corner. DM Brown was bought by House of Fraser in 1952 and changed its name to Arnott’s in 1972. It is now the home of Spanish fashion chain Zara, amongst others.

GL Wilson was opened in 1894, the year after Dundee became a city, and occupied the north-east corner of the junction, now Accessorize. Wilson’s was renowned for its magical Christmas Grotto, to which generations of young Dundonians were taken. Sir Garnet Wilson, who became the store’s owner and Lord Provost of Dundee during the Second World War, would often give the excited toddlers an extra penny as a gift. When GL Wilson closed over 40 years ago it was almost like a death in the family. Everyone shopped at ‘The Corner’.

Smith Brothers, on the opposite side and now The Body Shop, was famous for once supplying complimentary bowler hats to the town’s 60 cabbies. Smith’s provided 75 years of service before closing in 1970.

The High Street, Murraygate, Commercial Street crossroads.

MAP 1 ▪ G5–G6

The Murraygate

The Murraygate is another ancient thoroughfare and probably takes its name from Randolph, Earl of Moray, a relation of Robert the Bruce and the second signatory to the Declaration of Arbroath. It was Randolf in 1314 who captured Edinburgh Castle from the English during the Wars of Independence, famously using only 30 men.

Admiral Duncan