9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Seren

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

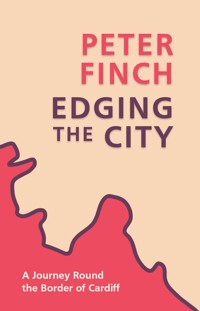

"What Edging the City does so effectively, though, is defamiliarize and enrich these landscapes, with allusion, digression and depth, all painted in seemingly effortless poetic prose. Finch lifts the apparently mundane to a place of real literary significance, giving some of these lesser-known quarters the attention they deserve."– Nation.Cymru Finch's writing is as jovial as it is fascinating…Edging The City is engaging in every sense of the word." – Buzz Magazine Peter Finch is perhaps the foremost chronicler of Cardiff, past and present. His response to the 2020 lockdown restrictions confining people to their local authority area was to begin walking the boundary of his. Full of insights and discoveries that will delight walkers and armchair travellers alike, Edging the City offers a view of Cardiff like no other.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 353

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Edging the City

Also by Peter Finch

Edging the Estuary

Real Cardiff

Real Cardiff Two

Real Cardiff Three

Real Cardiff: The Flourishing City

Real Wales

The Roots of Rock: from Cardiff to Mississippi and Back

Walking Cardiff

Poetry

The Machineries of Joy

Zen Cymru

Food

Useful

Poems for Ghosts

Selected Later Poems

Collected Poems (two volumes)

Seren is the book imprint of

Poetry Wales Press Ltd.

Suite 6, 4 Derwen Road, Bridgend, Wales, CF31 1LH

www.serenbooks.com

facebook.com/SerenBooks

twitter@SerenBooks

The right of Peter Finch to be identified as

the author of this work has been asserted in accordance

with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

© Peter Finch, 2022

Chapter heading images by Peter Finch

ISBN: 9781781726761

Ebook: 9781781726778

A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted at any time or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without

the prior permission of the copyright holder.

The publisher acknowledges the financial assistance of the Books Council of Wales.

Printed in Pelikan Basim, Turkey.

Contents

Introduction

The Precision of Borders

Finding Out Where They Are

Writing It All Down

The Walks

The Ferry Road Peninsula

Ely

The Caerau Hillfort

Culverhouse Cross

Michaelston

St Fagans

Capel Llanilltern

Rhiw Saeson

Ty’n-y-Coed

The Garth Mountain

Gwaelod

Castell Coch

Fforest Ganol

Caerphilly Mountain

Graig Llanishen

Graig Llysfaen

The Rudry Diversion

Cefn Mably

Buttercup Fields

Druidstone

Wentlooge

The Peterstone Gout Diversion

Lamby

The East Moors

The Tremorfa Diversion

The Foreshore Diversion

The Bay

The Barrage

Flat Holm

The Medieval Version

Running The Border

Sailing The Border

Endpiece

Sidebars

The Border Crossings

Eating My Way Around the Cardiff Border

Places Where Everyone Talks To You

Words For Mounds

The Coal Mines of Cardiff

Walking Kit

North Cardiff Trees

The Mountains of Cardiff

The Three Great Difficulties of Graig Llanishen in the Isle of Britain

Things That Follow You Around

Maps

Notes

Works Consulted

The Playlist

Acknowledgements & Thanks

About the Author

Introduction

Circumnavigating the city and then writing home had been on my mind ever since I’d encountered Iain Sinclair’s walk around the M25, London Orbital, which came out in 2002. But it was the Covid crisis that pushed it and the directive that for exercise citizens had to remain within the confines of their local authority. Stay Local. No border crossing. But what could that mean? Just how big was my local authority? How far out did it go and where did it end?

Back in the Cardiff booster days when asked how far out the city should stretch the then Council Leader Russell Goodway suggested Swansea. Present Council Leader Huw Thomas says he wouldn’t go quite that far. Either way Cardiff’s trajectory is for it to get larger.

Driven by pandemic restrictions ultra-runner Oli Smith had already decided to run the border for charity and was out there fundraising. In the wake of this, data journalist Callum Thomson suggested to me that as a Cardiff psychogeographer traversing the border might be an idea I could engage with. I took a look at the map.

Looking at Cardiff maps, of course, is something I’ve been doing all my life and in particular since I wrote my first book about the city at the start of the new millennium. Maps quantify, display, direct and enthral. They tell history, social as much as political. They show you what and they show you where. What they are not that good at is showing you how. Cardiff was there, a great lozenge shape. 7.93 miles bottom to top. 11.84 miles wide. You can cross it on foot in a day easily. Doing it by bike is a walk in the park.

Going around the outside rim, however, is not quite the same. The distance is considerably greater. Measured with a map wheel and following the precise zig and zag of the actual border it comes out at 41.59 miles. Finding walkable routes that follow this precise dotted line is another matter. Oli, who was hacking it in a single day, and much of that in the dark with a torch headband in place, took the view that climbing fences and wading small rivers was probably admissible in his adventurous and athletic circumstances. I felt that for the pedestrian something a little more formally legal and safer would be better.

I would follow the border by walking directly on it where this could be done. Where it couldn’t – and this happened fairly often – because perhaps the boundary ran up the centre of a river or crossed inaccessible private land, I would get as near as I could. I would travel within its range and, if not quite within sight of it, at least within its cultural footprint. Unless permitted I would not climb fences nor would I knowingly trespass. Where there was a formal route I would take it. Where not I would invent. I would also take a couple of minor diversions to points of interest a stone’s throw off. This is how the hillfort of Rhiw Saeson, Caerphilly Mountain top, Coed Coesau Whips, the Maenllwyd at Rudry and the spectacular Peterstone Gout (unforgivably part of Newport) all get coverage. The whole deal worked out at 72.76 miles (excluding my erroneous foray into the Port of Cardiff – described in Section 26 The Foreshore Diversion – which should not be duplicated). Purists will avoid these digressions. Their walks will be inevitably more accurate but inevitably less interesting.

Given its length and the fact that I also needed to write it up this border walk did not happen all in the same day. I spaced it over a period of months. Checking, walking, revisiting, walking again. Most of the thirty sections I’ve ended up with can be combined with each other to give great day walks of a length suitable for anyone. There is nothing here that should defeat, although a few hills rise excitingly. Elsewhere in the book there’s a list of refreshment stops strung around the whole fifty-five miles. Eating your way around the border is certainly possible. If you do please report back and we can compare notes.

The city’s area is around 140 square kilometres, 35,000 acres or 54 square miles. Some Texan cattle ranches are bigger. Before the border walk I imagined that the city would run out gradually as it approached its boundaries. Housing would slow and thicken with trees. There would be factories, warehouses, small industrial estates, shopping malls, hospitals, gateway roundabouts, sewage farms, electricity sub-stations, abandoned great houses, scrap metal yards, and dumping grounds for waste. And there are all of these things – these are quasi lands, fringe almost places, fuzzy interfaces between the suburban living and the industrial deceased. There would also be, I was sure, great new build housing estates as the City rolls into the future fulfilling its LDP (Local Development Plan1) original promise to build 41,000 new houses over the next two decades.

The problem with population forecasts is that they are forecasts. Recent work on the ever-evolving LDP2, the new RLDP (Revised Local Development Plan) of 2021 now projects Cardiff population growth between 2018 and 2026 to be a mere 8696 rather than the 39,346 they’d originally suggested. The 2026 total of 403,684 has now shrunk to 372,944. Why? Coronavirus, Brexit, error, don’t know. Maybe all these new houses won’t be needed after all.

I’ve tracked through some of the new estates. They sit up towards the City boundary with their cement and building detritus-filled streets, partially landscaped, starting to regreen. They are filled with shopless families who live here with their cars because, as of right now, the transport infrastructure needed for this kind of city-wide inflation has yet to be provided.

But what really surprised me were the vast tracts of flourishing farmland still in place. How Cardiff’s green belt, often thought to be massively under threat, appears in some quarters to be actually all there is. The northwest quarter, for example, is field after field and then field again with the M4 running traffic in a thin almost invisible line through the centre. Not quite the rural eighteenth century but with a flavour of that past extant still.

Traversing the hill ridges to the north I found much more that recalled how the pre-Cardiff world once would have been. Woodland succeeding woodland almost without break for mile after mile. But back in the south centre, where I start the walk, it’s not like that. Trees here down the Ferry Road peninsula need to be specially imported and nurtured well if they are to survive. The industrial city dockland might be in retreat but its replacement of apartment housing and intensified leisure hardly amounts to a regreening. For that we need planning regulation to be further adjusted in greenery’s favour.

This could all be now happening. As I write the Coed Caerdydd Project3, a co-operation between Council, Woodlands Trust and Welsh Government, is moving ahead with its prodigious new re-treeing of the city. The current 2658 hectare canopy of 1.4 million trees will ambitiously be expanded by a third. The target date for achieving this is 2030. New woodlands will be created. Schools and communities will be involved. Local tree nurseries will flourish. It could work.

Online maps for the whole Edging The City route and its diversions are here: Edging The City – Main Route - https://www.plotaroute.com/route/1864006

The Precision of Borders

“Territories allow people to be governed or taxed or imbued with loyalty by virtue of their shared spatial location, not their race or their kinship ties or their faith or their professional affiliation4.” – Professor of History and Guggenheim Memorial Fellow, Charles S. Maier.

But what is the border? I’m standing out here on the A48 between Cardiff and Newport where the map tells me it should be and evidence of border actuality is pretty much nil. Somewhere behind me is a sign that greets visitors to the capital and ahead is another welcoming arrivals to Newport. Yet between them is no fence or rising barrier, no wall with a gate, no watch towers, no mesh, naught. On the map there is a faint pecked line. On the ground which the map depicts there is nothing at all.

Cities are not states, of course. With a few notable exceptions – Singapore, the Vatican, and Monaco among them – they are not semi-autonomous countries anymore. They do not own their citizens as countries might do. In the long past territories were managed by the extent the tribe could travel. Borders were flexible, porous, ever shifting, constantly affected by fire and flood. Camps might have their edges defended but they would by necessity need to be swift in shifting when under attack.

Cities, when they evolved, were the first places to introduce formal barriers to the movement of their citizens. Early examples from antiquity, Uruk, Jericho and Troy, all had watch towers, gates and walls. Attack, if it came, was by siege. Defence was through weapons deployed along the battlements, the building of castles, keeps, towers and forts. In the absence of any actual historical castles the nearest equivalent to where I’m standing today would be the St Mellon’s Golf Club clubhouse with its stepped entrance porch, keg beer and bottles of IPA – but no boiling oil.

Borders for whole kingdoms, for countries, and for confederations were usually too geographically long to encourage definition through wall, ditch or palisaded bund. Although this certainly didn’t stop some ancient rulers from trying. Offa, King of Mercia, built a dyke (177 miles) along the edge of his territory although there is argument as to whether it was to defend against marauding Cymric tribes or to keep the Anglo-Saxons from straying. Hadrian’s Roman wall (73 miles) looks a defensive masterpiece but may well have been more a device for processing immigrants and collecting customs. The Great Wall of China stretched across an amazing 12,000 miles but was never entirely linked together and possesses a doubtful record as a defensive structure. The same fate befell France’s Maginot Line (280 miles) which looked impregnable but was never tested as the invading Germans simply went around it. More recently Trump’s Mexico border wall (1954 miles) failed simply by being too ambitious. Only the Soviets’ Berlin Wall at 27 miles long could ever have been said to completely function as a defining and impregnable border marker. It lasted twenty-eight years from 1961 to 1989 and it kept people in just as well as it kept people out. During those years the world knew where the Russian’s iron curtain with the west was situated for sure.

Cardiff’s border exerts no movement control over its citizens nor over anyone else. In fact, when looked at from a geopolitical perspective it actually exerts no control at all. It is a line on a map. Before the advent of maps the location of Cardiff’s borders was far less precise. But those in power always knew where they were. For a time borders were defined by the stone wall the town’s citizens erected. This was barricaded with gates and lookout towers. It was centred on a great one-time Roman but now Norman castle. There were two churches inside so in the event of attack God would be on Cardiff’s side. But then outer suburbs began to accumulate. Easier to get at space just beyond the walls became increasingly attractive. First Crockerton to the east and then Southey and the Moors to the south. Abandoning its built boundaries Cardiff grew larger.

Outside the readily demarcated boundaries of the early towns and cities – the curia of the Romans, the vills and manors of the feudal lords – villages, hamlets and farmsteads dotted the land. In a hierarchy of local judicial and administrative power they were grouped first into cantrefi or hundreds and those hundreds then marked out into parishes. Nomenclature shifts as you cross the land. Hundreds, wards, sokes, rapes, wapentakes, liberties. Which term you employed depended on where you were.

The parish, the most important early area division, began as a creation of the Church. Where you lived determined to which church you owed your annual tithe. This was originally a payment in support of the local clergy and was paid in kind. Following the Reformation the parish evolved to become a secular administrative unit with obligations to the poor and the ability to manage local taxation. Cardiff’s earliest were the Parish of St John, surrounding the Castle, and the Parish of St Mary, covering the streets running down to the South Gate.

Since Norman times Cardiff had been managed through a grant of authority and rights known as a Charter. These documents defined the town, its laws and enactments and the rights and obligations of its citizens. The earliest extant example dates from 1147 although it is certain that other charters now lost predated this. But maps that showed the extent of the town, its parishes, structures and features and from which its citizens could determine their own responsibilities remained a thing for the future.

Prior to the Inclosure Act of 1773, and in many places for centuries after, the boundaries of a parish were ingrained into the minds of local citizens by a custom known as the beating of the bounds. This was a walking of the parish border to show where it was. By custom beating the bounds was carried out annually at rogation, three days before Ascension. In some areas, for example in Llantrisant just north of Cardiff, the practice continues today. Markers on the route, great trees, stones, hedge rows, would often be given names. Customs developed where young people or new arrivals to the district were held upside down at certain points or had their heads struck against rocks in order that they might forever remember that this was where the boundary lay.

Carved stone markers indicating parish extent can be found in many lonely places. Sandstone pillars with initials on them or with metal plates attached. Some still exist in the wild reaches of Wales but few, if any, remain inside the confines of Cardiff. The City’s stone wall itself is almost entirely gone except for the run at the back of the raised flowerbed on Kingsway and the slab in the car park at the rear of Virgin Money on Queen Street. Its route is shown in the polished marble floor inside the St David’s Centre shopping mall and the existence of a gate marked by coloured tiles on the floor of a Quay Street car park (see p.233 for more). Reality retreats.

The past we once shared lingers in a few other markers. The Third Marquess of Bute, who regarded archaeology as essential, was keener than most on preserving what he could. He allowed the line of the Roman Fort to be shown when he reconstructed the Castle’s stone walls and kept the outline of Blackfriars Monastery in Bute Park by building low walls to run along the thresholds. The original monastery had been demolished following the reformation in 1538. The tiles and low walls on site today are probably not the originals but the shape is correct. An ancient boundary marked on the surface of the contemporary world.

At Thompson’s Park in Pontcanna the land that the heir to the Spillers Milling fortune, Charles Thompson, donated to the city in 1912 was delineated by seventeen boundary stones marked with Roman numerals. These are indicated on the maps of the period. The stones still exist, ten of them. Stones I, IV, XI, XII, XVI & XVII are missing. Cardiff’s earliest map was included in John Speed’s Theatre of the Empire of Great Britaine of 1611. This showed the town in elevation, with houses drawn in perspective and the walls, as mentioned earlier, rendered as they might have been by a child.

Borders became considerably less imprecise when maps showing the extent of a landowner’s estate began to be incorporated into legal documents. Who owned what, who leased it and at what rent were of increasing importance. David Stewart’s property survey carried out for landowner the Marquess of Bute in 1824 was one of the first to show a full rendering of the town border. This appears marked as ‘the old wall’ and runs from the castle to the canal basin wharf beyond the South Gate. Speculative surveyor and map maker Michael Spain O’Rourke’s plan of the larger Cardiff of 1849 depicts the border in similar style.

It isn’t until Thomas Waring’s four inch to the mile plan of the town twenty years later that Parish Boundaries begin to appear. Waring was Resident Engineer for the Cardiff Sewage Works, a surveyor, and architect of, among other things, the original Guildford Crescent Baths. His plan shows not only the lines of the Parishes of St John and St Mary but the Boundary of the Parliamentary Borough of Cardiff. This line runs along the centre of the Roath Brook. Albany Road is in the heart of the burgeoning town. The great houses of Penylan Hill are cast out into the country.

Ordnance Survey began its century long mapping project for the entire of Great Britain and Ireland in earnest at the end of the eighteenth century. New surveying equipment had become available. On the new surveys boundaries of everything were included – lakes, rivers, bays, lagoons, ponds, coasts, tide lines, parishes, hundreds, shires, counties, districts and regions. Areas of military sensitivity of possible use to the country’s enemies were left blank5. The Survey’s lines were precise. If they followed a stream or hedge, as ancient parish boundaries often did, then the dotted line would be supplemented with initials such as C.S., R.H., and C.W. (centre of stream, root of hedge, centre of wall). Their maps for Cardiff – viewable online at both the National Library of Wales and The National Library of Scotland – are things of beauty.

The formal border that defines the City and County of Cardiff today is the result of an accumulation of history, contemporary administrative precision, guesswork and whim. It follows the past as much as it decides the present. In some places it is within the flow of a river. In others it tracks the bank of a winding, serpentine, fractious stream. It jerks to square across the centres of fields. It leaps hedges as often as it slavishly follows them. It does precisely the same with roads and tracks.

I get the feeling, following it, that half of the route I am on was set in times well before those of the Romans. This border has outlasted centuries of land ownership shift, parish border manipulation, parliamentary constituency ratification and the thrashing of the tides.

On other occasions I find myself walking something that is incredibly new, decided arbitrarily by a map maker or plotted to earn even greater profits by a speculator of land. Industry through the centuries has also staked its claim, obliterating ancient boundaries with the territory mashing development of iron works, steel works, transport systems, interchanges, rail stations, canalised rivers and the creation of the quaysides that make up the port. The land of Cardiff becomes Cardiff because some of us have decided that it should be like that. It’s how we’ve acted since the Romans were here.

Back on Newport Road I still have no absolute idea where the border crosses. My phone GPS shows a blobby red arrow. Precise enough.

Finding Out Where They Are

The natural instinct of boundaries, and in particular ancient boundaries, is to avoid rather than confront. In The History of the Countryside Oliver Rackham reports a parish boundary between Butcombe and Wrington in Somerset as having two unexplained semi-circular deviations from the true along a field’s edge. Investigating on the ground he discovers that the Wrington semi-circles represent the edges of circular prehistoric enclosures. Hut circles. The parish line would not cut them through but rather went round. It followed the line of least resistance. I’ve found pretty much the same along the Cardiff boundary. For the most part the line follows natural features. In the northwest the Pentyrch boundary with RCT is marked by vibrant wiggle-disposed lines that track every twist and slew of any number of tributary streams. It runs mid-water, usually, as a guard against future riverbank dispute. As a boundary it is as old as the land it defines.

Along motorways and bypasses the border takes an edge rather than a centre and carefully cuts around bridges and embankments so that future maintenance responsibility lies with a single authority rather than be fought over by two. Hardly ever on this fifty plus miles ramble have I discovered a borderline running through the centre of a built structure. Despite near misses on Began Road, a few difficult moments near Taff’s Well, the Blaengwynlais Quarry border straddle, and a minor wobble near the Caesars Arms in Creigau the usual route is around.

Hay-on-Wye is a town not only right on the county border between Brecknockshire and Herefordshire but also on the line that separates the lands of England from those of Wales. Here the border manages to cut right through a house’s centre. Giving birth in this residence a century back a woman was dragged at the critical moment into the room’s English quarter so that her child could claim that country as their nationality. Being English then gave you advantage. Something I’m not sure totally holds today.

Planning regulations require that where a development straddles two local authorities an application for the entire proposal should be made to both. Only one fee is charged and that by the authority on whose territory the larger part of the development is situated. The LAs then work out where the border will go. Not down the middle of a room any longer, for sure.

Boundary changes have been with us as long as there have been boundaries. Originally these were fought over with weapons of war. These days it’s down to words, influence, and shouty voices. Local Government boundary change as an instrument of political advantage is always out there in the wings. Parliamentary constituencies are altered in response to growing (or dying) populations. Democracy demands fair and equitable representation. Boundary commissions are set up to recommend changes. Those changes are regularly fought over, always amended, and sometimes never enacted at all.

As Cardiff grew so did its outer borders. In 1802 Cardiff used an enclosure act to incorporate sections of the Great Heath, which had a racecourse and was thus the obvious choice. In 1875, powered by the industrial revolution and the need for more workers’ accommodation, the town annexed what are today the inner suburbs of Adamsdown, Splott, Canton, Grangetown and Roath. Back then they were mere villages. In 1922 Ely, Llanishen and Llandaf were added. 1938 brought Rumney and Trowbridge. 1951 added Llanrumney. 1967 Whitchurch, Rhiwbina, Llanedeyrn. 1970 Danescourt. 1974 Lisvane, St Fagans, Tongwynlais, St Mellons, Radyr, Morganstown. 1996 Pentyrch and Creigau. 2023 who knows.

The names the town chooses for its constituent parts have their own myths and evolutions. A Cardiff street directory from 1893 shows The Moors, The Town and Newtown, areas we do not recognise today. Proposals for changes in nomenclature sometimes fail. Nobody liked the 2016 plans to hive off a slice of Penylan and call it Ty Gwyn so that didn’t happen. However, about the same time other parts of the city were divided to formally create Thornhill, Pontcanna, Llanedeyrn and Tremorfa, districts I thought already existed.

We’ve got to look with care at the terms in use. Are these neighbourhoods, communities, districts, areas, suburbs, constituencies, or wards? The Roath Local History Society has tracked the history of the Roath name to discover that at various times it has meant almost half the city while at others it was either genuinely tiny or, for one brief period, didn’t exist at all. On that occasion the name Roath had been replaced with Plasnewydd, not a term dear to many inhabitants’ hearts.

Deep in the city’s local administration new entities are already emerging. Fresh neighbourhood localities have been created. Which of these six new divisions do you live in: Cardiff West, Cardiff North, Cardiff East, Cardiff South East, Cardiff City & South, or Cardiff South West? Turns out I’m in the north when I always thought I was in the east.

In 2012 there was a proposal to create a new parliamentary seat which included areas of both north Cardiff and the southern sections of Caerphilly. On this occasion it was defeated but that is how expansion begins. Or goes on. Down on the flatlands Newport presses back at the Capital City and, so far, after viewing evidence on the ground, it looks as if Newport is winning.

Out at sea the border is in another place altogether. Here among the tide’s boundaries are subject to a different set of rules. Cardiff’s sea border is a thing all to itself. Much of the UK foreshore is owned by the Crown Estate although in Cardiff a large amount has been leased to others. The shoreline itself has spent centuries advancing and retreating at the caprice of climate change. Alluvium deposit, erosion and human intervention all affect where it runs. Lying out there in the centre of the Severn Estuary when the river was a tumbling gush set in a narrow deep gorge. Receding to the current line of the railway when most of Cardiff’s southern face was salt marsh and mud. Bute and his fellow businessmen kept shifting the town’s edge south as they reclaimed acres of land from the sea’s tides in order to build docks on them. That foreshore path along the rocks and shrub used by sea fishermen south of the Queen Alexandra Dock was deep in the estuary waters as recently as the end of the nineteenth century.

The estuary we gaze out at today has so many authorities, managers, federations, supervisory bodies, conventions, associations, agencies, councils, actors and regimes regulating its existence that it resembles a creation of Franz Kafka. My copy of the Strategy for the Severn Estuary lists 135 organisations with an active interest in Bristol Channel matters. Boundaries abound. Area Sectors, Unitary Borders, Wetland Trust Perimeters, Port Authority Boundaries, Commercial Shipping Areas, Water Classification Regions, Licenced Dredging Boundaries, Sea Fish Trawling Zones, Historic Landscapes, SSSIs, RAMSARs, and then the line down the middle that demarks England forever from Wales.

A current battle sits out there on the south western corner of Flat Holm. Since 1066 the island has been included within the parish boundaries of St Mary’s in Cardiff. In 1975 it was leased from its owners, the Crown Estate, by South Glamorgan County Council. That lease transferred to Cardiff in 1995. Flat Holm was as much a part of Wales as Steep Holm to its south was part of England. This, however, hasn’t stopped the UK Boundary Commission allocating a few Flat Holm sea shore rocks to the Parliamentary Constituency of Bristol North West, England. The Commission’s map shows this audacious Argentinian-style land grab as “for development purposes only”. Whatever that might mean. Cardiff needs to strengthen its island defences.

Elsewhere southern extent of the city is precisely defined by its tideline. That originally being the high-water line of ordinary tides, changed in 1868 to the low water line of ordinary tides and resolved since 1965 as the mean tide line. After early employment of meresmen (boundary checkers) to track these lines the OS, whose job it was, surveyed the precise tide lines by sending gallant surveyors out onto the low-lying flats with their equipment and their boots. Special allowances were payable for water and mud damage to their clothes. Risks were run as tides would turn and cut the surveyors off. “Temporal uncertainty and meteorological conditions6” brought the accuracy of the surveyed line into doubt. It took until the advent of aerial photography for the precise seaward border to be formally settled. Today GPS and other satellite-based radionavigation systems make the extent of Cardiff unassailably confirmed.

Writing It All Down

Is walking a mild leisure pursuit or an obsession? I was from a family that rarely walked for pleasure. In 1960 I’d read in the newspaper, my father’s folded copy of The Daily Mirror, of a woman who was walking all the way from John O’Groats to Land’s End. Dr Barbara Moore. She wore a conventional mac and soft shoes. Crowds came out to cheer her as she went by. I found it unbelievable. To walk that distance, unaided, without buses or cars. She did it too. When it was announced that she’d reached Land’s End my mother dealt with this impossible achievement simply by refusing to believe it had happened. The following month Billy Butlin cashed in on the whole process by announcing a mass walk along the same route. 715 people set out and 138 reached the other end.

There was a buzz to all this. I began consider the possibility that my family’s sedentary practices might not be the best ones. Even my hero of the time, Jack Kerouac, king of beats and hitchhiker supreme did a huge amount of walking. He treated the entire process as a Buddhist experience.

In the early 80s on a trip to Cornwall I bought Roger Jones’ Green Road To Land’s End7, the story of the author’s walking expedition of 400 miles duration from Chiswick to Cape Cornwall. Distance, as Jones proves, is indeed possible. In his book he provides an inventoried account of his problems with walking boots, blisters, routes, weather, river-crossings, wrong turnings, people, overnight stays and the food he eats. While no William Nicholson, Nicholson Baker, or Georges Perec – and certainly no Marcel Proust – writers who all major on detail – Jones’ book was an entrée to a world of walking minutiae that was for me previously unencountered.

Back at the bookshop I was then running, Oriel in Charles Street, Cardiff, culture and language were viewed as more important than turnover. Writers and painters would gather to browse their long lunchtimes and endless Saturdays while listening to the Chieftains and Alan Stivell lapping out of the sound system. For increased alternative cultural currency I installed a twirly of Paladin Books. Paladin was a paperback imprint of Granada Books devoted to what today might be called cult interests but back then were popular centrepieces of the alternative society. A.H.A. Hogg’s Guide to the Hillforts of Britain, Rowland Parker’s Men of Dunwich, Janet and Colin Bord’s The Secret Country, Nic Cohn’s Awopbopaloobop Alopbamboom, Victor Pananek’s Design for the Real World and John Hillaby’s Journey Through Britain8. This last-mentioned title covered the author’s ramble right across Britain in an adventurous mountain and moor crossing of eleven hundred miles from Land’s End to John O’Groats. Up there with the poetry9, philosophy, revisionist history and new age psychiatry it was a constant seller.

Reading it again now through the fifty-year rear-view mirror it’s easy to see why. Hillaby is Jones with style, range extended, detail reduced, prodigious storytelling added and a way of describing the sheer unoccupied vastness of British (and particularly Scottish) mountain ranges that is absolutely unequalled.

When the new millennium dawned I came up with the idea of writing a book about the fragmented life of being in a city. It was a book I wanted to function, as near as I could make it, like the then brand new web sites that were filling our screens. Click and jump, narrative moved sideways, data added, expanded, viewpoint altered. A real picture of the city world would emerge. This was Real Cardiff #1. To date twenty-five further real titles have followed.

In the same year Penguin Books brought out Nicholas Crane’s length of the country walk in Two Degrees West – An English Journey10. Walking and then writing about it had become a recognised genre. Crane, however, added a new dimension. He would walk along the line of 2° West. This was the only line of longitude running through Britain marked on the maps of the Ordnance Survey. They called it the Central Meridian. Crane’s line went through no major tourist spots and barely bothered with big cities. He decided to restrict himself to a 2000 metre corridor astride this longitude line and walk. When he came to fences he climbed over. Rivers he waded. One lake he took a boat across and one tumultuously rainy night he hitched a half-mile lift to a B&B but mostly he just walked. It’s an amazing tale of planning, daring, innovation, and great writing.

Here was a man who’d set up some rules and wrote about his experiences as he followed them. A bit like trying to walk the streets of a city in alphabetical order (which I’ve tried and can report as impossible) or tracking that city’s border (which I’ve also tried as you, the reader, are by now aware. How successful I’ve been is something you’ll no doubt be letting me know, some of you).

Crane would go on to become an umbrella-wielding presenter on the TV series Coast and, in a great lean towards popularism, President of the Royal Geographical Society. He has also written just as entertainingly and informatively about his travels on foot right across Europe from Cape Finisterre to Istanbul on the edge of Asia. Clear Waters Rising – A Mountain Walk Across Europe11 is full of the same spirit which got the author down the Central Meridian. He’s also come up with one of the best expositions I’ve come across of why landscape is like it is and how it became so. The Making of the British Landscape12 is an essential handbook for anyone trying to understand the shape and history of the world around them.

It was Will Self, however, who dramatically changed my perception. In 2007 he published a fat hardback entitled Psychogeography13. This was essentially a collection of his Independent columns of the same name but it began with the startlingly-titled piece, Walking To New York in which the author does just that in order to test not only the personality of the places he traverses but their deep topography (to use Nick Papadimitriou’s term) as well. This turns out to involve “minutely detailed multi-level examinations of select locales that impact upon the writer’s own microscopic inner-eye”. It also includes knowing the place’s “ecology, history, poetry and sociology”. To that I’d add its politics, its music, the shape of its spirit and its weather. It also involves cheating. You can’t walk to New York from here, can you? There’s an ocean that gets in the way. Instead Self walks from his home in Stockwell, south London, to Heathrow where he catches a plane. He also walks, presumably, from JFK right into Manhattan but that section of his book skims some of the detail. Nevertheless the principle is there. Self has marked it out.

Many have written about circumnavigating capital cities. You can find their tales on the web. David McAnish did Paris14, one of psychogeography’s two main centres (the other being London), in six days. He reckoned it was only thirty-five miles right round. He wrote up his travails for The New York Times. He is more tourist than investigator. He goes round counter-clockwise returning to his hotel by Metro at the end of each stint. The grand Parisienne psychogeographic excitements of the Boulevard Périphérique, the remains of the vanishing nineteenth century Thiers Wall, and the unsettling interface between the city of lights and the festering suburbs that make up the encircling banlieues all get walk-on mentions but no detail.

Berlin is circled by the Ringbahn, a 37.5 kilometre rail line that takes in the former west and east Berlin city centres. Photographer and journalist Paul Sullivan followed its route sticking as close as he could to the actual tracks. Employing the spirit of psychogeography he navigated rivers and canals, waste spaces, down at heel cafes, ruined structures, miles of inner-city graffiti and wrecked industry.

He has encounters with security guards and pulls in a myriad cross-cultural references illuminating everything with his own dramatic edge-land photographs. The train journey would have taken him an hour or so. His feet managed it in a few days. The former would have provided a fleeting experience, the latter gives us a masterpiece15.

Iain Sinclair, poet, antiquarian bookdealer, and leading manipulator of contemporary London psychogeography has made more explorations across the UK capital than most. His seminal Lights Out For The Territory16 from 1997 set the standard. Described as a deranged David Bellamy or an off the wall De Quincey Sinclair explores a different city from the one most see. His is solid with literary association, jagged leys of spiritual power and startling discoveries. The companions he takes on his travels appear as characters in a novel. His Finnegan’s Wake of a plot remakes the oddball, the cult and the blatantly avant-garde as mainstream.

When it was first opened in October 1986 the M25, the London orbital motorway, an Anglo-Saxon Périphérique, a Ringbahn for cars, was designed to carry 100,000 vehicles daily. By 2003 that number had risen to 196,000. It’s continued to rise steadily ever since. Not all, of course, go all the way round. But just for the hell of it a number do. You can’t travel around the city like that in Cardiff. We have too many hills, too many rivers and too much sea.

Undaunted by the M25’s dimensions, in fact excited by them, Sinclair has gone on to walk the whole circuit remaining inside the motorway’s aural footprint, staying near it enough to be in its influence. London Orbital17 is the result. He walks mostly with a friend and provides the reader with a detailed dialogue of discovery. These city boundaries and the edges of their hinterlands are filled with the lost, the empty, the wrecked, the poor and the mad. They are dumping grounds for the yet to be reconstructed and the deserted. Sinclair’s circuit is carried out via a series of loops for which he provides no maps. Those wanting to follow in his footsteps will have a hard time. But as a psychogeographic adventure the book has few equals.

He begins at Waltham Abbey, the grave of King Harold, and within the shadow of the motorway. He walks anticlockwise. Stalks, he calls it. It’s 1998 and the millennium and all its mad festivities and panics have yet to happen. Two years later the work finishes on Millennium eve. “We hadn’t walked around the perimeter of London,” he writes, “we had circumnavigated the Dome.” It’s out there, at a safe distance, built on a swamp in East London, “Glowing in the dark”.

Sinclair’s passion for circumnavigation allows him to route around London again, a dozen or more books later, in 2012. This time he follows a railway, the Ginger Line, in a day. London Overground18. Thirty-three stations, thirty-five miles and an amount of sleight of hand to fit it all into a twenty-four hour remapping of the city.

“The world of flows is erasing the world of places” declare Diener and Hagen19, academics in the new discipline of Border Studies. Geography is done. The homogenised borderless landscape is upon us. Maybe. Say that to the immigration officers in Dover or the American guards with night sight rifles down on the Mexican Border.

The Border Crossings

Routes out of the city. List runs clockwise starting at the southern tip of the Ferry Road peninsular.

1. Pont y Werin footbridge

2. A4055 on stilts running west to Penarth

3. A4232 on stilts – the Grangetown Ely Link

4. A4160 – Penarth Road – by the Pumping Station

5. Leslie Hore-Belisha’s 1934 B4267 Leckwith Bridge

6. The 1536 stone bridge

7. The underpass from Trelai Park Leckwith Woods

8. Cwrt yr Ala Road under the A4232 at the Caerau hillfort

9. Caerau Lane

10.