3,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Next Chapter

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

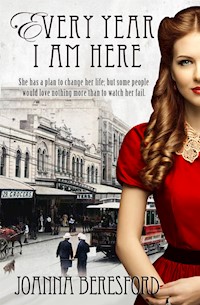

Irreverent and resourceful, Lillian Betts has her dreams. But in 1891, a woman with ambitions to rise into the city's upper echelon requires more than hopes and wishes.

One problem is Lillian's a maid, who's snatching illicit kisses with her employer's son. Another is her sister, who wants her help caring for illegitimate babies in exchange for premiums.

Taking a well-earned rest in Dutton Park, Lillian witnesses a mother deliver her baby in a grove of trees and abandon it. She must make a quick decision - one that may very well snuff out all her hopes of becoming a lady.

For secrets are hard to keep, and some people would love nothing more than to watch her fail.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

EVERY YEAR I AM HERE

JOANNA BERESFORD

Copyright (C) 2021 Joanna Beresford

Layout design and Copyright (C) 2022 by Next Chapter

Published 2022 by Next Chapter

Edited by Terry Hughes

Cover design: Helen Goltz.

Woman in red dress: By Inara Prusakova, Shutterstock

Background image: Brisbane c.1897. John Oxley, State Library of Queensland.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the author’s permission.

CONTENTS

Part I

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Part II

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Acknowledgments

You may also like

About the Author

For my dad, Alex

PARTI

A kind person with no children would like to adopt baby; small premium. Alice, Post Office, Valley.

ADVERTISEMENT IN THE QUEENSLANDER, 1891

CHAPTER1

DUTTON PARK, BRISBANE, AUSTRALIA, NOVEMBER 1891

Lillian heard the woman before she spied her. A primitive groan carried on the breeze, causing her to lower the paintbrush in her right hand. She scanned the scrub one hundred yards to her left. There a figure crouched, partly hidden behind a thicket of stringy-bark and banksia, with skirt and petticoat pulled up to reveal slender thighs.

Lillian sucked in a breath of tangy eucalyptus and tried to slink out of sight; she already had enough troubles of her own. However, her unwieldy corset prevented such a measure. There was nothing to do except remain upright. Besides, curiosity exceeded her usual sense of decorum as she watched the woman writhe on the ground.

Over the past hour, Dutton Park had become deserted. Not a picnicker or ferryman appeared to be about for Lillian to summon any help. It was unusual for a Sunday afternoon. Until that moment, she had been glad of the peace and quiet, painting her watercolour and pretending to be the fine lady she was not… yet. How had the stranger managed to escape her notice?

The seconds turned into excruciating minutes. In the branches, currawongs called to each other, piercing whistles soaring above a cicada chorus. A quick rustle beneath the leaf litter sent a thrill of alarm up her spine. The half-finished watercolour puckered on the open sketchbook and Lillian’s dream of being able to pull herself out of a miserable domestic position slid farther away. Green ants scurried by her boots. In that fugitive state, aware any movement might alert the struggler to her presence, at last relief was granted.

The woman’s long mane swung as she lurched then sank against peeling bark. Lillian watched her drag an olive-green shawl from her shoulders to wipe the sweat away from her face and neck. The stranger then dropped the wrap on to the ground and fiddled with it. Finally, she rearranged her skirt and petticoat and staggered back on to her feet.

The poor waif was simply dressed in a grey skirt and white cotton blouse still buttoned up to her throat. Even from that distance, Lillian could see the ordeal had left dirt smudged all over her cuffs and elbows. There was no way to get a good look at her face.

Still unsteady, the stranger weaved through the adjoining cemetery’s headstones and headed in the direction of small cottages marking the park’s perimeter.

Lillian waited until she had vanished from sight before rising to stretch her legs. They prickled all over with pins and needles as blood flow was restored, forcing her to hop from one foot to the other for relief. She bent down to snap the paintbox lid shut and packed it into her basket along with the brush. With the sketchbook tucked firmly into the crook of her arm, she wandered over to where the woman had struggled.

The infant was silent, wrapped tightly in the knitted shawl and nestled on a bed of leaves and twigs. Flies and ants had already begun to infest the puddled afterbirth lying nearby. A couple of larger insects crawled over the baby’s slick hair to suckle at sealed eyes. Lillian wished she could say she was surprised to see the sorry sight but she had witnessed each of her sister’s labours. The moment she’d laid eyes on the stranger, it was clear birth was imminent.

She darted another look at the cottages and shivered. Were they concealing witnesses to her conundrum? What on earth was she going to do? She’d specially chosen Dutton Park – a good mile’s walk from West End – because she had been craving some solitude. The shameful stray had usurped the last of her precious time. Why else would a mother have left her baby behind unless it was illegitimate?

Lillian thought again of her sister and her worries intensified. Patricia would be fretting about why she hadn’t yet returned from her walk, not because she was worried about her but because she wanted extra help with the children. Lillian felt frozen with indecision. She had a plan to change her life. It was possible to do such a thing in the colony – her mother had always said so, even if her own dream had shrivelled the moment her foot had stepped ashore.

Lillian finally stooped to bat the flies away from the newborn’s twitching nose. The gesture proved futile; the insects immediately returned to continue their scavenging. She crouched on her haunches and tugged the woollen wrap from the little one’s body to discover its sex. It was a boy and a healthy-looking one at that. The umbilical cord had roughly been severed; by scissors, a knife or teeth, Lillian couldn’t tell. His mother had at least had enough sense to tie it off tightly with a small piece of twine.

The baby’s fair-skinned belly rose and fell. Every part of him appeared to be located where it should, except for a large wine-coloured birthmark discolouring his right thigh. Lillian traced her finger around its irregular circumference. He wriggled in response, screwing his face up until he resembled a grumpy old man. She smiled and picked up a corner of the shawl that remained unmarred by dirt to wipe the muck out of his eyes and mouth. He was ugly in the squashed-up way newborns always were yet also quite adorable, especially the way he blinked up at her with old-soul eyes and began to squawk. She was already beginning to fall in love with him and the thought depressed her. Before his tiny siren could gain traction, she quickly wrapped his plump body up nice and secure again. As she tucked in the last corner, a piece of paper slipped from the layers. Lillian unfolded and discovered it to be a promissory note, to the value of one pound. She refolded it and slid it between her top two blouse buttons to lodge it safely between her breasts.

A crunching step on dry bark and a small movement flashed at the corner of her eye. Scared, Lillian glanced around her yet couldn’t see anything out of the ordinary. She gently laid her hands on the newborn and felt his warmth emanate from the yarn. There was the sound again. Instinctively, Lillian pulled her own shawl up over her mouth and her bonnet down and twisted back toward where she had been painting. Another girl, younger than herself, stood like an apparition. A buzz filled Lillian’s ears. The cicadas’ cacophony re-entered her consciousness. She snatched the baby from where he was resting and began to run. Her shawl flapped against her face as she neared the girl, who instinctively held her arms out in self-defence.

‘Please, you must take him,’ Lillian murmured, thrusting the precious bundle straight into them.

Without looking back, she hurried out to Gladstone Road – the thread to stitch her back to the safety of the West End and her sister. Unfortunately, the baby was of no use to Lillian, even though she missed him already. She’d never be allowed to keep him.

CHAPTER2

GOOD DECISIONS

With lungs on fire, Lillian raced along Gladstone Road, drawing ever closer to Patricia’s house. Her heart pounded as she put a mile between herself and Dutton Park. The younger girl had screamed with outrage the moment she found herself clutching the baby. Lillian imagined her finger pointing towards the city like a compass. Any Good Samaritan emerging from the cottages to see what the matter was would easily be convinced to set chase after the culprit who had committed such a callous deed. They would drag her straight to the police station if they caught her. Lillian shuddered at the idea of having to defend herself against charges of child abandonment. The fact she’d not been the slightest bit pregnant that morning did nothing to quell her distress. She was a worrier. Patricia always teased her for blowing situations with a justifiable explanation out of proportion. At that moment, Lillian’s nervousness knew no bounds but, despite her panic, she forced herself to throw a glance back over her shoulder. Nobody was coming.

She pulled the shawl fringe from her mouth, slowed to a trot and began to feel foolish. It was such a relief finally to reach Musgrave Park, so close to home, and stop for a moment on a park bench to take a rest.

Sweat beaded on her forehead and under her arms, soaking into her cotton blouse. Whether because of shifting the problem on to another girl or knowing how her brother-in-law would react if she’d brought the baby home, her stomach was churning. She collapsed on to a bench beneath a sprawling Moreton Bay fig tree until her heartbeat returned to normal and she felt well enough again to complete the last leg of the journey.

Lillian found her sister in the kitchen, head bent, darning a sock.

Patricia looked up and frowned before resuming stitching more vigorously than the task required. ‘Where have you been? You said you would only be gone for two hours. Why did you bother coming home at all if you weren’t going to spend any time with us?’

Lillian contemplated a pile of unwashed clothes in a wicker basket, cooking utensils scattered across the table, and her younger nephew, Thomas, kneeling on the floor rolling a toy train. She scooped him up and pulled him on to her hip. He clutched his train with his left hand and entwined the pudgy fingers of his right around the strands of hair at her nape.

‘Ow! Be gentle, little chum,’ she murmured against his apricot ear.

Lillian took a seat at the table and manoeuvred the small boy so he faced his mother. She tickled him until he erupted with laughter. The ploy to lighten her sister’s mood worked somewhat. Patricia set her darning down, licked her thumb and smeared it across her son’s cheek.

Still sitting, Lillian craned her neck to see into the adjoining parlour. ‘What’ve you done with Peter?’

Patricia studied Thomas’s face for signs of more grime. ‘Alf took him to the wharf to watch the sailboats. The yacht club’s holding a regatta today.’

‘Isn’t that nice of him?’ Lillian couldn’t hide her sarcasm any better than her sister knew how to suppress her irritation. She was sorry Patricia had ended up married to an oaf. At least from observing them she knew what not to accept from a future suitor. Hers would be a marriage of the heart and the purse.

‘He’s doing his best,’ Patricia snapped. ‘You can keep your judgement to yourself, thank you very much.’

‘Oh, so it’s all right for you to say mean things about him but not me? I see how it is.’ Lillian paused before trying to cajole another smile from her sister. ‘Very well, I’m sorry. I didn’t want to be out for so long.’ She meant what she said, even though none of it had been her fault.

Patricia pushed her sleeves all the way up past her elbows, revealing forearms browned by the summer sun. Long, delicate fingers that would have been far better suited to piano playing – if only they’d grown up in a different world – resumed flying rhythmically as she turned her attention back to the sock.

In a final effort to placate, before she’d have to admit the whole afternoon was a complete disaster, Lillian decided to confess the reason for her tardiness. Her conscience needed soothing. It was impossible to decide on her own whether the decision to pass the baby to a girl even younger than herself had been the right one or not. It certainly didn’t feel right. She didn’t need to be a mother herself to know that. The image of her unsuspecting saviour rose sharply in her mind. The girl wore an embroidered dress and hat, a mother-of-pearl comb pinned back her rich brown wavy hair and a pair of gold drops hung from her ears. A split-second glance had told Lillian everything she needed to know – the baby would be safe. The girl no doubt had a wealthy, respectable mother who would know what to do, not a poor, dead one like hers and Patricia’s.

For her sister, Lillian loosened the truth: the other girl had offered to carry the baby boy off to the Diamantina Orphanage, which conveniently sat across the road from the cemetery in Dutton Park. Her breath hitched, torn between choosing that ending instead of a much nicer one, where the girl took the baby to her mother instead, to adopt him instantly into the bosom of their luxurious home. In the end, Lillian felt it best to keep her explanation realistic. Even after sharing her contrivance, Lillian found the burden on her conscience only slightly allayed and it disappointed her.

‘Goodness! Poor little chap,’ Patricia said. ‘What a fright for you. Lucky somebody else was on hand to help. I suppose The Diam really is the best place for the child if his mother can’t care for him but doesn’t it only take babies when families can’t afford to keep them? What would a married woman be doing in the middle of a park giving birth by herself?’

Lillian raised an eyebrow.

Patricia tilted her head to one side and rolled her eyes. ‘Yes, well, it’s still unfortunate. I hope a nurse took him in. It’s hardly the baby’s fault.’

Lillian pointed to a slab of bread sitting on a wooden board at the far end of the table. ‘Can I have a piece?’

Patricia nodded. ‘Yes, do. I saved the last of the butter for you as well. After you’ve eaten, would you be a dear and bring in the dry washing so I can hang out the next lot? If you can fold it as well, that would be lovely.’

Lillian felt glad to be able to conclude the visit on a happy note. Easing Thomas back to the floor to continue playing with his train, she descended the three wooden steps beyond the back door and collected napkins from the line of wire strung up between two leaning posts. The honeysuckle climbing the side of the outhouse in the far left corner of the yard released a pleasant scent. Patricia’s vegetable patch was flourishing along the fence. Her sister had a successful green thumb, which was fortunate because her lazy husband wasn’t good at providing very much at all those days. At least Alfred’s industrious father had had the grim foresight to bestow on his son a deposit for the cottage as a wedding gift.

With his miserly approach to spending on his family, despite the fact Alfred had been out of work for eight weeks, he hadn’t yet felt the pinch like many others living in the West End. Lillian suspected Alfred also had other nefarious ways and means to make a pound, ways she hadn’t yet uncovered. To her disgust, she knew – indeed had seen with her own eyes – how he’d begun to enjoy the extra idle hours… by spending her own hard-earned money at the Terminus Hotel over on Melbourne Street.

The screen door slammed against the outside wall as she unclipped the last sun-warmed napkin.

‘Lillian. There you are.’

Alfred swayed on the top step. His voice grated. It was just as well there wasn’t another hour to spare to have to listen to him prattle on.

‘Alfred.’ She acknowledged him through gritted teeth and did her best to keep her expression neutral. ‘Did you enjoy watching the race with Peter?’

Patricia hovered behind her husband’s shoulder, her nostrils flaring. Lillian kept her own sharp tongue on a leash. What had happened to the determined person she used to turn to for advice? Who was this quivering ghost in the shape of her sister? It was a crying shame.

‘Yes, but unfortunately Peter tripped over his own feet and fell over. I had to bring him straight home to his mother because he wouldn’t bloody stop crying.’ Alfred looked down at his son with disappointment. ‘Would ya, boy?’

Lillian watched her elder nephew whimper behind his father’s legs. Fell or pushed? Alfred’s temper didn’t flare only at Patricia.

‘I really must be heading back,’ she said. Anything to avoid being caught up in his avalanche of self-pity.

Despite his injury, Peter burst past his father into the yard. ‘Aunt Lillie, I don’t want you to go!’

‘Sorry, Peter, but I must. I promise to come back next weekend like I always do.’ Despite his pleas, she urgently wished to rid herself of all of them.

‘Have you given Patricia your wages yet?’ Alfred asked.

Lillian grabbed her nephew’s small dimpled hands and swooped him around in wide circles. The promissory note scratched against her skin as she swung him back to happiness and disguised her scowl. ‘Yes I did.’ Well, most of it, except for two small coins well hidden under her bed. They were an investment in her future, one without the hateful Alfred in it. At the current rate, she feared she’d be a wrinkly old spinster by the time the plan could be put in motion.

‘Good girl.’

Lillian slowed and deposited Peter unsteadily back to earth. It was time to retrieve her basket and go. Loading her arms up with clean napkins, she walked to the back steps.

Alfred did not attempt to move.

‘Excuse me please, Alf. I have to say goodbye to Patricia.’

‘She’s busy.’

‘Alfred, please. She asked me to fold the napkins before I leave.’ Lillian was careful not to let a whine creep into her voice.

‘Listen to you. Haven’t you learned a few airs and graces working in that fancy house? Don’t forget I was the one who found you that position.’ His glare dared her to protest but she would not grant him the satisfaction of an argument.

‘See you next Sunday, Patricia!’ she called out instead, depositing the napkins on the step at Alfred’s feet. She crouched in front of Peter and pulled him into a hug. ‘Be a very good boy for me, won’t you? Do you understand?’

The little boy nodded.

‘Look after your mother.’

She pecked his cheek and straightened, pretending not to see the way Alfred warily watched them.

‘Aren’t you going to give your brother a kiss goodbye, too?’

She ignored him and hurried to the side of the house, rushing up the space between the wall and fence while Alfred’s derisive laughter trailed after her. Angry, she strode up on to the veranda, flung the front door open and flew up the narrow hall to snatch her basket.

Patricia looked aghast. Lillian quickly blew her a kiss as Alfred spun on the back step, knocked the clean napkins into the dirt, and lunged at her. Too quick for his grasp, she ducked back up the hall out of harm’s way.

‘Oi, get back here!’ Alfred shouted.

Mrs Lin, from the market garden further up the road, was wandering past the front gate. The elderly woman swung a startled glance between Alfred and Lillian as they erupted from the cottage. Her expression swiftly descended into disapproval. The whole street would soon know their sorry business.

Lillian scuttled past and curtly nodded a greeting, still expecting Alfred’s hand on her shoulder at any moment. Risking a quick glance back, she saw the front porch remained empty. He’d obviously been chastened by the presence of a witness and retreated, deciding she wasn’t worth the bother of a public chase. She knew he would not forgive nor forget her impertinence yet euphoria set in at having foiled him. Each instance where she managed to evade his authority held a hollow victory. However, a needle of discomfit pricked at her. Patricia would be the one to bear the brunt of his chagrin that evening. Lillian chided herself for being selfish but there were so precious few other outlets available to be able to express her frustration.

After such an eventful afternoon, with two lucky escapes, it was a relief to head back to her own lodgings. It had initially infuriated her when Alfred secured her a position at Rosemead. Before Alfred was dismissed, when his boss, Mr Shaw, had mentioned he was in need of reliable domestic staff, he’d wasted no time offering her up. Lillian had watched her brother-in-law sit at the kitchen table to fabricate a reference before sealing it in an envelope. He’d given her instructions to hand it over on arrival at the stately Kangaroo Point address.

She would not be indebted to Alfred. She would not! He was her sister’s first poor decision, not hers. Rounding the corner, Lillian paused to whisper a curse upon his head.

Brisbane River forged beneath Victoria Bridge as she crossed it, sidestepping hand-swinging promenaders and the Sunday devout. She decided to take advantage, before the light faded, to detour through Queen’s Park. Alfred’s hold began to weaken as the greenery pressed in on her senses. The injustice of being unable to kiss her sister goodbye abated. The scent of gardenias wafted across the late afternoon air, evoking memories of their mother’s favourite perfume; a large bottle had always sat on the tiny oak dressing table in their room. Lillian remembered watching her carefully squeeze a spray behind each ear as she readied for an evening of entertaining. Rather than producing sadness at the memory, the scent comforted.

Up ahead, the Edward Street ferry pulled into the wharf, which served to set Lillian’s spirits right once and for all. No dawdling, simply a step aboard for the final leg of the trip. It would not do to be late.

As she turned into Shafston Road, the Shaws’ immaculate mansion loomed up ahead. The large brick house decorated with lacy balustrade was set back into a sprawling front lawn and separated from the street by a white picket fence. Even as shadows began to fall across the grass court stretching alongside the property, Mrs Shaw and her daughter, Olivia, continued to play a tennis match. With a sigh, Lillian stepped over the property’s threshold and braced herself for another week of domestic drudgery.

A rush of wind overhead frightened her. She batted her hands in the air and looked up in time to see a black-and-white blur materialise into a magpie. The fiend alighted in the branches of a large elm planted inside the gate and stared down. Not wishing to receive another dive-bombing, Lillian raced to the back porch. Except for a cursory glance to see what the fuss had been about, the players ignored her, as was their custom. She would have received a greater shock if Mrs Shaw and Olivia had rushed over to try with their rackets to save her from the bird.

Still perturbed, Lillian entered the house and traipsed up two flights of stairs to the stuffy attic she shared with Catherine. Her roommate was a Scotswoman who spoke with a thick Glaswegian brogue and, other than her sister, was the only friend Lillian felt she had. With Patricia so busy with Alfred, her children, and keeping up the cottage, it had been a relief to find another ally. At three years older, Catherine always seemed to have a word of wisdom to help keep her spirits up.

For the moment though, the room was empty. In fact, the whole house seemed far too quiet. Mrs Menzies, who doubled both as cook and housekeeper, would be outside collecting herbs or feeding scraps to the chickens. In her hurry to get inside, Lillian hadn’t had time to look around the garden. She didn’t know when Catherine would return from visiting her friends. It couldn’t be much longer; dinner needed to be prepared and ready to serve by six o’clock.

Lillian unbuttoned her boots and slipped them off her stockinged feet. They had gathered plenty of dust from the roads that afternoon. She dipped her handkerchief into the pitcher sitting on the washstand. It still held some water from her morning wash. She’d been in too much of a rush to finish her chores and leave for Patricia’s to bother emptying it. Picking up a boot and dotting two eyes and a slip of a smile on to the leather, she then reached over to the dresser and retrieved a polish kit. Mrs Shaw might not worry herself about saving a servant from an avian attacker but she would notice immediately if Lillian dared serve her dinner up while looking the slightest bit shabby.

Beyond the closed door, the floorboards emitted a steady squeaking. Catherine must have returned. Lillian expectantly waited to greet her but Donald Shaw poked his head around the door instead. His face broke into a grin. From the hopeful look, he obviously believed she was happy to see him.

She clutched her quilt and froze. He’d never been so brazen.

‘Hello, Lillian.’

‘Hello,’ she murmured back.

Donald slid inside the room and sauntered over, taking one of the bedstead’s brass domes into his palm to caress it. Seizing an uninvited seat, he took in the meagre decorations around the room: a portrait of Catherine’s brothers hanging on the wall, a silver candlestick on the nightstand that had been Lillian’s mother’s, and a cast-off embroidered hand towel hanging off the washstand. Donald’s silk waistcoat and the gleaming gold watch chain hanging from his breast pocket made a mockery of the sparseness.

‘Did you have a pleasant time at your sister’s this afternoon?’

‘Yes, I did. Thank you for asking.’

‘I’m glad to hear it.’ He smoothed the worn pattern on her quilt with his long, well-manicured fingers.

Donald was Mr and Mrs Shaw’s younger son. At twenty, he was a full year older than she was. Lord knew her mother and Patricia had drummed in the message of abstinence the moment her monthly blood began to flow. It was unfair of him to dangle himself in front of her like a carrot on a string before a goat. She could have screamed. She could have run right out the door. The path was clear.

Lillian didn’t want to do either. After all, Donald had been the secret object of her desire since the moment he’d strolled, cock-sure, into the kitchen while she’d been working and stolen a thick slice of ham off a serving platter. He’d put a finger to his lips and winked at her right as Mrs Menzies – cantankerous woman that she was – turned around and caught him red-handed.

Lillian had struggled to contain her laughter.

‘Get away, you scallywag!’ Mrs Menzies had shouted.

The cold cut was intended for him anyway. It was of no consequence to Donald whether he took it by stealth or had it served up to him alongside the rest of the family. He’d simply bowed his head with mock contrition at the cook’s tirade and retreated to the dining room.

They were lucky, Mrs Menzies, Catherine and herself. Donald possessed a naturally sunny disposition. The trouble for Mrs Menzies was she had known him since he was a rambunctious child. Now he’d grown into manhood, he was well within his rights to order them all about, and yet he refrained. His spoilt little sister, Olivia, on the other hand, was a churlish, sly witch of a girl who took every opportunity to remind all of them of their proper station within the house.

Lillian felt light-headed with Donald sitting on her bed cheekily beckoning her to come sit a little closer. Did he forget she was the one who had the task of emptying his chamber pot each morning? She knew more about his bowel habits than he did, yet being the recipient of such unsavoury knowledge did nothing to discourage her affection for him.

She had a ridiculous urge to confess what had happened at Dutton Park that afternoon. Perhaps her callousness would shock him enough to leave her alone for good? What did he care about women’s private matters? He might even report her. She couldn’t risk losing such a bright flame in an otherwise dull existence.

Donald, who rode a strong mare and had been born with a cricket bat in his hands, would never understand the desperation that drove a young woman to discard her own flesh and blood. Lillian could scarcely make sense of the woman’s actions herself. Would he shudder if she pulled back the curtain on the reality life held for lesser mortals? All those very same reasons were precisely why she found him so attractive. Donald understood how to enjoy his privilege and made no apologies for it. He lent her a glimmer of hope that one day – if she made very good decisions – it would be possible to be able to do the same, despite their beginnings in life being so unequal.

Undeterred by her reluctance, Donald edged closer and slowly connected the tips of their fingers. She held her breath and kept her eyes firmly fixed on his. He did not make personal resolutions easy to keep.

‘I missed seeing your friendly face about the house today,’ he said.

‘I –’

His lips were upon hers quickly and hungrily. She pressed into his hands that were pawing at her blouse.

A steady thumping of boots shook them both immediately to their feet before Catherine entered the small space.

‘Och, no!’ The Scotswoman scanned the scene before her and, deciding no harm had yet been done, barged past to plonk down on her own bed. ‘Get out of here, Donald. Yer cannae get Lillian and me into trouble.’

He raised his palms to show the moment between them was well and truly dispelled and exited without objection. Lillian wished he wouldn’t let Catherine push him around; she was only a servant.

‘For Christ’s sake, Lil. Cannae ye at least be locking the door?’ Catherine lay back, flung an arm across her eyes and loudly yawned.

‘I didn’t invite him in.’

‘I dinnae care whit yer do but at least be careful, hen. Why yer’d want to spend any time with that cheeky bastard is completely beyond me.’

‘He’s not! Donald works very hard and has impeccable manners.’

‘If his manners are so impeccable, whit’s he doing in a room he shouldnae be with a maid whose reputation is the only thing of value she has?’

Lillian poked out her tongue and fetched her apron and cap from where they hung on a hook on the back of the door. Catherine had an answer for everything.

As her infuriating friend’s eyes were concealed, Lillian retrieved with some difficulty the bank note from where it had slipped down inside her corset. She crouched beside her bed and rummaged under the mattress to find a slit she had created months ago. The note slid between her other treasures: a cherished illustrated copy of her childhood favourite, Pinocchio, the only photograph ever taken of herself and a small cloth bag filled with hard-saved coins. She would need to find a better long-term solution for all these items but for now there was no time. She rose and finished tying her apron strings about her waist before securing the cap to her hair with several hairpins.

‘Catherine, aren’t you going to come down and help?’

‘Aye, in a wee bit. By the way, I’d be putting those paints back from where they came before anybody discovers yer’ve been thieving.’

Lillian’s basket and its paraphernalia jutted halfway out from beneath the bed, where she’d hastily kicked it as Donald entered.

She blushed. ‘I was only borrowing them.’

‘I won’t tell Mrs Shaw yer a crook if yer dinnae tell her I was taking a wee nap instead of getting ready to work.’ Catherine slowly lifted her arm and winked. ‘By the way, if I’d wanted to steal yer things I’d have done it a long time ago. Yer far too suspicious.’

So Catherine knew about her hiding place after all? Lillian sheepishly plucked the paint box from the basket. She quickly rinsed the brushes but left them and the sketchbook behind. She’d managed to save for the latter by withholding two measly pennies a week from Alfred and Patricia.

Heading down one flight of stairs to the first floor, Lillian ventured on to the landing and paused to make sure nobody else was about. The dull and steady rhythmic thwacking of a tennis ball on catgut strings satisfied her the ladies of the house were still busy playing tennis, despite there being scarcely any light left to see by. She continued along to Olivia’s room, carefully turned the brass doorknob to avoid squeaking and entered.

Shut safely inside the cavernous and rather luxuriously appointed room, Lillian crept over to the cherrywood writing desk stationed beneath the tall sash window. She pulled open the lid and slid the paintbox back on to a little shelf where it had been sitting that morning.

She never feared being caught; she was quite adept at arranging items so the owner never noticed a thing missing. Pickpocketing clients who had imbibed one too many glasses of Madame Claudette’s finest brandy was a skill all the children she had grown up with had quickly honed, even if Patricia liked to pretend she’d been above such dishonesty. Even if the men who frequented the bawdy house realised they’d been robbed, they were unlikely to report the petty crime to a constable. For her own part, how else was she going to further her education and interests if she wasn’t prepared to make use of the available equipment needed to be able to do so? A lady should be well-versed in literature and art and that was precisely what Lillian intended to be one day; a lady, and a sophisticated one at that. She didn’t know quite how just yet, but it was certainly going to happen. It infuriated her to see expensive materials go to waste when there was an opportunity to make some money from them. If she could demonstrate her artistic ability to the owners of one of the exclusive shops, perhaps the offer of an apprenticeship would be forthcoming. The cinders in her belly stoked into flames at the thought.

It had been obvious to all of Rosemead’s occupants that Olivia’s foray into watercolours was going to be brief. The spiteful girl had furiously balled up a failed landscape in front of her father when he’d dared to compliment her and thrown the offending page straight into the lit drawing-room fireplace. While Mr Shaw was a very successful and formidable solicitor, it appeared he was no match for his spoilt sixteen-year-old daughter. Lillian felt quite certain Olivia had long forgotten she even owned the paintbox. Still, she hoped Catherine wouldn’t use the knowledge of her misconduct to hold her to ransom later. It was true the Scot had never given any reason for Lillian to doubt her but one could never be too careful.

Shuffling steps sounded out on the landing. Lillian held her breath lest she was about to be caught without even a cloth in her hand for dusting. There should be no other reason at that time of the evening for her to be entering Olivia’s bedroom. Catherine was the one who took care of the linen and bed-making, not her. The fear of punishment made her shiver. Whoever it was passed by, much to her relief. She hastily exited and hurried down the final flight of stairs into the safety of the kitchen.

Mrs Menzies had reappeared and was busy setting a pie on the table next to a freshly picked bunch of parsley that needed chopping.

‘There you are, Lillian! Where have you been? And where’s Catherine?’

Mrs Menzies never seemed pleased to see either girl. Lillian supposed the chore of coordinating cooked meals for ten mouths every single night was enough of a reason for the woman’s prickly demeanour. The cook used the same accusing tone as Patricia had earlier. Unlike Patricia, Mrs Menzies would not relent for an embroidered excuse. Lillian wisely kept her mouth shut and did her best to look contrite.

‘Here. The family will be inside shortly for their tea. Go set the silver. Once you’ve done that, come back and start cutting up those herbs.’ Mrs Menzies wiped her hands on her apron and pointed at the parsley.

Lillian did as she was told.

When the family had assembled around the mahogany table, their patriarch, Mr Henry Shaw, closed his eyes and delivered grace with his usual aplomb. Lillian suppressed a laugh at Donald’s irreverent glances as his father’s tightly closed eyes sent bushy eyebrows dancing. It was frivolity on her part to think Donald might hold sincere affection toward her. Surely he thought of her as no more than a toy? Play with her he certainly had those past few months.

Even the sight of Fergus, Donald’s older brother, also still a bachelor – with his immaculately pomaded hair and handkerchief peeping from his breast pocket – failed to amuse her that evening. Ordinarily she found Fergus a source of fascination. He courted a carousel of women, being eligible with inheritable wealth and a position at his father’s firm. He also enjoyed horsing about with Alfred and the other chaps they’d attended school with more than ten years ago. That evening, though, her thoughts continued to be clouded by the baby she’d been forced to leave in the park.

‘Whit’re yer doing?’

The carpet came into focus and Lillian realised she’d been caught head down in a stupor. Catherine had slipped up behind her and she hadn’t even noticed.

‘Nothing.’

‘Olivia’s been staring daggers at yer, waiting for her glass to be refilled.’

Lillian glanced across the table and saw the sour girl scowling back. She hurried over with the decanter.

‘Best be getting yerself back to the kitchen before Cook throws a right wee fit,’ said Catherine as Lillian returned to her side.

She clutched at Catherine’s sleeve. ‘I’ve done a terrible thing.’

‘Well whitever it is, hen, surely it cannae be as bad as holding up the dinner service. Come on now.’

Lillian dutifully followed her back to the kitchen and refilled the decanter as Catherine retrieved a large dish of roasted vegetables from the sideboard. Despite the steaming aroma tantalising her nostrils, Lillian’s appetite had completely disappeared.

Outside, darkness descended the same way it had inside her.

CHAPTER3

KANGAROO POINT

Lillian awoke to find herself twisted up inside her sheets with her nightgown sticking to her back. She’d been dreaming of ants crawling all over her skin and found herself still clawing away at the imaginary creatures on her arms. A peek under the curtain revealed a still-black sky.

She couldn’t rightly leave in the middle of the night to go and make sure the poor baby had indeed been taken out of the park, but she wanted to very much. She could have left that baby on the steps of the Methodist church or the Anglican cathedral or the Diamantina herself. Had her hasty actions doomed her as an accomplice to murder? Surely the wretched mother was lying in her own bed somewhere and praying someone had used the pound note to feed, clothe and love her son? The other younger witness had looked so helpless when Lillian had shirked responsibility like a morbid game of pass the parcel.

She wrenched the bedclothes from her limbs and drifted back into an uneasy sleep.

Catherine shook her by the shoulders and peered down at her with concern. ‘Hey, yer were talking in your sleep.’

Lillian rubbed her puffy eyes. ‘What did I say?’

Catherine slid her arms inside her shirt sleeves. ‘I couldn’t tell whit yer were blethering on about. Must have been something to do with that terrible thing yer did.’

‘Pardon?’ Lillian struggled to sit up, startled.

Catherine laughed. ‘I’m only teasing, hen. Remember? Yer said as much last night but didnae mention whit it was you’d done.’

‘I did, didn’t I?’

‘Whit was it then, the terrible thing yer did?’ Catherine’s face was lit up with mischief as she finished buttoning her shirt.

Lillian racked her brain. ‘I… I let Donald put his hand underneath my skirt and touch my knee.’ The excuse sounded weak, even to her.

Catherine playfully squashed Lillian’s cheeks between her warm palms. ‘Scandalous. As if I didnae know about that already. For a wee moment I thought yer’d done something criminal.’

Lillian gulped. ‘Of course not.’

‘Whitever it is, yer’ll keep. I’ll get yer secret out of yer one way or another.’ Catherine retreated to her own bed. She reached for her boots, put them on and hurriedly laced them up. ‘See yer in the kitchen. Yer’d better hurry up.’

Catherine left as Lillian reluctantly rose, feeling weary from her disrupted night’s sleep. She filled the washstand bowl with water from the jug her bedfellow had already retrieved from the well and washed her face and body to get rid of the stale perspiration that had left her feeling sticky all over. Today marked one year since her arrival at Rosemead. The anniversary was an unpleasant reminder there were several months of stultifying heat ahead to endure in the poky attic. The thought did not cause much distress: she was used to being uncomfortable. She wiped herself down with a rough towel, patted at her eyes and got dressed. The temperature lowered by several degrees as she plodded downstairs.

As Lillian entered the kitchen a loud squeal shattered the morning quiet and immediately roused her from her fugue.

Mrs Menzies turned to Catherine. ‘Now who on earth do you think that could be?’

‘Maybe Olivia found a wee cockroach in her bed.’

‘We can only hope,’ said Lillian.

‘That’s enough from you two.’ Cook whipped a dishcloth at them. ‘Whoever it is, they’re somewhere out the front.’

The shrieking and shouting intensified, which spurred all three of them to hurry down the hall and burst out on to the wide veranda beside Mrs Shaw and Olivia, who were holding their hands to their mouths. The sight in front of them was worse than Lillian could have imagined.

Beyond the gate, an exquisitely dressed young woman was clutching her left ear with fright. The same magpie that had bothered Lillian yesterday afternoon was in the middle of a repeat bombardment on its newest victim. On its next descent, the bird succeeded in knocking the woman’s bonnet to a crazy angle. The lady had already fallen from her bicycle, which now lay twisted on the ground. Her efforts to retrieve it one-handed while attempting to ward off her attacker were proving ineffectual.

What made the spectacle truly disastrous was the moment Donald pushed through the onlooking huddle clutching a tennis racket and taking aim at the marauder. His bravado gave the victim time to seek shelter behind his hastily tucked-in shirt. Satisfied the bird was temporarily warded off, Donald bent to retrieve the bicycle and set it upright. He then offered his arm to the poor woman. She gratefully tucked her gloved hand into the crook of his elbow and held on for dear life.

Something about the sight of them standing together, Donald’s face etched with concern while keeping a wary look-out, made Lillian feel truly sick to her stomach. He wheeled the bicycle up the front path and leant it against the balustrading before ushering his prize past her. His mother and sister hurried anxiously inside after them. As the young lady had passed, Lillian noticed the pristine white gloves held to her ear had bright bloodstains seeping into them. The wheels were responsible, of course. While that naughty magpie had swooped at Lillian’s head the previous night, the gesture had merely been a warning. It was the passing carts, bicycles and dogs the creature detested above all else.

Mrs Shaw dispatched her to retrieve iodine and cotton wool from the medicine cabinet. Lillian returned to the drawing-room in time to see the visitor being gently guided to the ottoman. The young woman found herself immediately flanked on the seat by Olivia and Mrs Shaw. Lillian slunk into a corner and listened as the stranger told them both in faintly clipped English tones that her Christian name was Mary and that she and her family, the Forsyths, lived not far from the Observatory at Spring Hill.

Mrs Shaw launched a polite but steady stream of questions to ascertain that Miss Mary was the daughter of the respected doctor, Joseph Forsyth. As if her father’s esteemed position weren’t enough to pique interest, the guest went on to explain that her mother, Mrs Elizabeth Forsyth, was an active supporter of the Society of the Prevention of Cruelty as well as local suffragist activities.

‘A progressive lady indeed,’ Mrs Shaw exclaimed. ‘I myself am a longstanding member of the Diamantina Orphanage Ladies’ Committee; since its inception, actually. I should think your mother and I might have quite a bit to talk about if we were to meet. Tell me, dear Mary, which church does your family attend?’

‘All Saints on Wickham Terrace. It’s Anglican. You may have already been able to tell I’m English by my accent.’ Mary covered her self-effacing smile with her glove before remembering it was soiled with blood. Embarrassed, she quickly lowered her hand back to her lap and tried to cover it with the less affected one.