Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

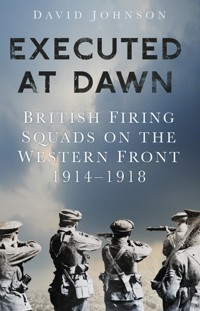

Much has been written about the 302 British and Commonwealth soldiers who were executed for military offences during the First World War, but there is usually only a passing reference to those who took part – the members of the firing squad, the officer in charge, the medical officer and the padre. What are their stories? Through extensive research, David Johnson explores the controversial story of the men forced to shoot their fellow Tommies, examining how they were selected; how they were treated before, during, and after the executions; and why there were so many procedural variations in the way that the executions were conducted.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 309

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

In memory of my mother

Winifred Johnson

11 January 1923–21 February 2014

CONTENTS

Title

Dedication

Introduction

1 The Organisation of the Executions:The Regulatory Framework

2 The Selection of the Firing Squad

3 The Firing Squad

4 The Army Chaplain

5 The Medical Officer

6 The Military Police and the Assistant Provost Marshal

7 Abolition of the Death Penalty in the British Army

8 The Campaign for Pardons for Those Executed

Conclusion

Appendix 1: Statement Made by Dr John Reid, Armed Forces Minister, on 24 July 1998

Appendix 2: Written Ministerial Statement by Des Browne, Secretary of State for Defence, on 18 September 2006

Appendix 3: Report of an Adjournment Debate Held in the House of Commons on 3 March 2009: The Story of Private James Smith

Appendix 4: The Last Letter Home from Private Albert Troughton of the 1st Royal Welch Fusiliers, who was Executed on 22 April 1915, Having Been Found Guilty of Desertion

Bibliography

Copyright

For Those Shot For Cowardice

by A.R. (David) Lewis

Their voices echo down the years, demanding justice:

‘It’s the noise, echoing, rebounding in the muddy trenches,

the shells continuous, shrieking, exploding in front and rear.’

I just wandered off, not knowing who, or what I was.

I’m not afraid to die, it’s living in this hell,

that causes the problem – I start to shake – my mind goes dead.’

Then the finger pointing General ‘No time for cowards,

court martial them. Stamp out this cancer’

Court martial’s obligatory verdict guilty – punishment death.

Shell shock – trauma – just excuses for cowards.

Then the voices of the firing squads are also heard.

‘The poor devil was legless, his brain already dead.

His bowels running out of control. He called for his Mam,

as we tied him to the chair he talked to her’

‘What are they doing to me, Mam?

I can’t see you, Mam, they have covered my eyes.

Sorry Mam, I have messed myself. Help me, Mam.’

The executioners once more, ‘What a way to die,

his blood mingling with the filth in his trousers.

God forgive me my part in his death.’

And still the voices of the dead cry out.

‘I’m not a coward – no blindfold for me,

I will look death full in the face – I am not guilty.

Shot as a coward, no pension for my wife.’

Dead – Not Dishonoured

by A.R. (David) Lewis

At four in the morning, the shelling restarted.

Their shrieking and screaming, the only sound heard.

Stand to at five, advance at five thirty.

Knee deep in mud the soldiers waited,

to hear the whistle, the command to advance.

The young lad waited, head bowed, trembling.

Praying ‘Please let’s go – get out of this noise.’

Lips not moving, mind chanting ‘Let’s go, let’s go.’

Not afraid to charge forward to meet his fate,

the mud, the noise, the waiting caused his trauma.

The enemy now returned the shelling, increasing the bedlam,

adding the crunch and exploding noises.

The Soldiers cursed, and finished their smokes.

The young one now visibly shaking, not in control.

He dropped his rifle, turned and ran.

The regulation court martial just a formality.

The verdict ‘Guilty’. The sentence ‘Death.’

Shell shock not mentioned, cowardice was.

The dishonoured young man to die at dawn.

His breakfast half a mug of rum, and five bullets to follow.

David Lewis is a prolific writer of prose and poetry (visit www.proprose.co.uk) who was born in 1919 and served with the Welsh Guards from 1938 to 1946, taking in both Dunkirk and the Normandy landings. David Lewis has kindly contributed three of his poems, which I am proud to include in this book. With his agreement, I have included two of these on the preceding pages and the third can be found at the end of the book. David has maintained a long-standing interest in the Shot at Dawn campaign, which he still considers to have some unfinished business in the sense that the complete story has not yet been told.

INTRODUCTION

In 2009 I went on a tour of the Western Front, visiting Ypres, Passchendaele, the Messines Ridge, Ploegsteert, Arras, Vimy Ridge and the Somme, and I saw the execution post at Poperinghe. Reading about those places is one thing, but actually to be there is a truly powerful experience that I would recommend to anyone. Words cannot describe the emotional effect of visiting the immaculately maintained military cemeteries with their rows and rows of white headstones stretching off into the distance, or indeed attending the moving ceremony held at the Menin Gate in Ypres every evening. The headstones mark the final resting place of thousands of men killed in action, but in addition they also contain the graves of those who were executed, shot at dawn, by the British Army.

Poperinghe New Military Cemetery. As a major military centre just behind the lines that was relatively safe and close to Ypres, the town of Poperinghe (now Poperinge) was the location of numerous courts martial and executions. (Courtesy of Paul Kendall, author of Aisne 1914 and Bullecourt 1917)

† † †

In the First World War, 302 British and Commonwealth soldiers, representing about one in ten of those condemned, were executed for military offences committed whilst on active service on the Western Front (Babington, 2002) and we know the names and the circumstances of those shot thanks to the research of Julian Putkowski and Julian Sykes in Shot at Dawn, first published in 1989, and that of Cathryn Corns and John Hughes-Wilson in Blindfold and Alone in 2001.

The books written so far have tended to focus on the controversy surrounding their cases and the court martial processes involved, and therefore it is not my intention in this book to go over that ground again, except where it is necessary for contextual purposes. My focus is on military executions post-confirmation of the sentence, and it seems appropriate therefore that the book should consider the issues of abolition and pardons. In doing this the book will examine the executions from the perspective of the members of the firing squad, the officers in charge, the army chaplains, the medical officers and the others who would have been present apart from those who took part, because, unsurprisingly, much less is known about them.

Soldiers have always had a natural reticence to speak to their families about the fighting that they have been involved in and the horrors that they have witnessed. If speaking about killing the enemy is so difficult, then how much harder it would have been to speak about witnessing or taking part in the execution of one of your own, perhaps even someone that you had known or had enlisted with in one of the so-called ‘pals battalions’. It is almost impossible to imagine what it must have been like living with those images in your mind – particularly in smaller communities where relatives and friends of the deceased may have frequented the same shops, factories and public houses as you, and as a result may have asked you awkward questions in an effort to find out how a loved one had died.

Unfortunately many of those who took part in British military executions were themselves killed in later combat and therefore the story of their involvement may be thought to have died with them. However, it has been possible to discover some of their names and some of their stories. Investigating events that took place a century ago means that there are now no opportunities for primary research, as even those who fought and survived are now all dead, and the opportunity to speak to them has long passed. This book, therefore, relies on secondary research drawing on what has already been published, together with personal and regimental diaries and letters, where these exist. It is through that research that the book will seek to explore and tell the stories of how those involved were selected, how they were treated before, during, and after the executions, and why there appears to have been so many procedural variations in the way that the executions were conducted on the Western Front.

I believe that all research must have a question at its heart, and it is this last point that fulfils that role. The British Army was at the time of the First World War, as it is now, a highly regulated organisation, with the smallest detail of army life set out in the Army Acts, military law and the King’s Regulations, and so it is not unreasonable to assume that executions would have been regulated and consistent, in accordance with a form of established ‘standard operating procedure’, to ensure that they were conducted as humanely as possible.

In turn, it would not be unreasonable to ask why a century later this might still be of interest to anyone. The truthful response is that although this book will not change anything, I believe it is a worthwhile subject to explore because it will add to the knowledge and understanding of yet another aspect of the First World War. Executions are an aspect of the First World War that still remains a source of discomfort to many, and yet they are a part of the story of that conflict and continue to cast their long shadow over a century later.

The book will also discuss the related issues of the abolition of the death penalty in the British Army and the campaign to secure pardons for those executed.

In addition, there is a link between this book and my previous one (One Soldier and Hitler, 1918, hardback/The Man Who Didn’t Shoot Hitler, paperback), which is a biography of Private Henry Tandey, VC, DCM, MM, the most decorated British private soldier to survive the First World War. In that book I wrote about the case of Drummer Frederick Rose of the 2nd Battalion of the Yorkshire Regiment (later to be known as the Green Howards) who was executed for desertion.

Drummer Rose would almost certainly have been known to Henry, as they served in the same battalion and would have headed off to Flanders together in August 1914. However, in December 1914 Rose had deserted his battalion and remained absent until December 1916. He was sentenced to death and executed by firing squad on 4 March 1917, by which time Henry was hospitalised in Britain for treatment to a wound received at the Battle of the Somme. Therefore, he was spared having to witness, or even be a member of, the firing squad. But it made me realise how close Henry had come to being part of one of these executions. As Henry did not appear to have kept a diary, sent letters to family or friends, or talked to them about his experiences, it is impossible to know his views on the death penalty or of taking part in a firing squad, but it set me thinking, and the result is this book.

I have not set out to be judgemental about the individuals that have been identified because they were largely behaving according to the standards of the time. I approached this book from a neutral position, allowing the theory or narrative to emerge from the research, and what I started to find was that there is still much to be debated about the conduct and behaviour of the British Army and politicians, not just in the war years but in the subsequent decades too.

† † †

Whilst writing, a number of times I have experienced the feeling of reaching a plateau in my work. I have been in this position enough times to know that something is needed to push my work onto the next level, and fortunately something always seems to come along that provides that necessary impetus. In this case it happened at a time when my work, while not exactly stalled, could be said to be progressing slowly, and my thoughts by way of self-distraction turned to whom I could ask to write the foreword. Eventually, through researching the Shot at Dawn campaign, I made contact with Mac Macdonald of the organisation FLOW (Forces Literary Organisation Worldwide), which has as its mission:

To help anyone who has suffered from the effects of war, including the suffering shared by family members and friends too.

The organisation believes, based on research that proves its therapeutic value, that the writing of a poem or a piece of prose provides an opportunity to release deep emotions in a safe environment, and that reading what others have written helps individuals to take comfort from the thought that others have been through similar experiences. The website is well worth a visit: www.flowforall.org.

FLOW’s website includes some material from the Shot at Dawn campaign and, with the help of Mac Macdonald, I was able to contact Mr A.R. (David) Lewis who was very supportive of my work on this subject and as a result gave me his generous permission to use his poems in this book. I am also very grateful to Mac Macdonald for passing on to me a file of documents relating to the Shot at Dawn campaign.

Many other people have generously helped me, and thanks and acknowledgements are due to the following:

John Hughes-Wilson, David Blake (Museum of Army Chaplaincy), Richard Callaghan (Royal Military Police Museum), Julian Putkowski, Scott Flaving (Yorkshire Regiment), Shaun Barrington, Jo de Vries and Rebecca Newton (The History Press), Mainstream Publishing for permission to quote from To War with God by Peter Fiennes, Colin Williams and Neil Cobbett at The National Archives, the staff at the National Army Museum, and last but not least my wife Val.

I have made all reasonable efforts to ensure that all quotations within this book have been included with the full consent of the copyright holders. In the event that copyright holders had not responded prior to publication, then should they so wish, they are invited to contact the publishers so that any necessary corrections may be made in any future editions of this book.

I believe that all research must inevitably raise more questions than it answers, and I hope that others may be motivated to debate and further research the issues raised in this book, and to come forward with any additional evidence that will either confirm or disprove my analysis.

David Johnson

1

THE ORGANISATION OFTHE EXECUTIONS: THEREGULATORY FRAMEWORK

The condemned man had spent his last night on this earth in a small room that was barely furnished with a table, two chairs and a straw bed. By the light of a guttering candle he had written his final, painful letters to his family and friends, and laid out his few personal possessions on the table. The small room was further diminished in size by the presence of two guards, who stood with bayonets fixed by the door and the single window to prevent his escape.

Occasionally through the night, the chaplain came to spend time with him, but otherwise he sat alone with his thoughts. With his letters written, he decided that he would spend his last hours awake and, so, moving his chair so that he could watch for the approach of dawn through the window, he started on the bottle of rum that had been left on the table. Inevitably, he fell asleep, only to be roused by the sound of footsteps and voices outside the door.

It was just before dawn and the sky was starting to get light as a small group of men was marched into an unused quarry. They were then left to stand around smoking and looking anywhere but at each other, not wanting to catch another’s eye, the smoke from their cigarettes and pipes drifting upwards to add to the slight mistiness of the morning. Some stared at the ground, some examined their hands, and some stared into the middle distance. Most definitely, nobody wanted to speak, as they all knew what they were there to do.

A short distance away stood the lonely figure of the young lieutenant in charge of the firing party, his face pale from the knowledge of what was to come. He smoked ferociously and stamped his feet in an effort to keep warm while he nervously checked and re-checked his service revolver, worried that this morning of all mornings it might jam.

Two companies of the condemned man’s regiment then marched silently into the quarry and took up position across its open end, and, in response to a shouted order, stood at ease.

Soon, too soon for some, they heard the approach of a vehicle, and a motor ambulance appeared at the edge of the quarry. The members of the firing squad were then called to attention, facing away from the stake that none of them had been able to look at, with their rifles placed on a tarpaulin on the ground behind them.

The condemned man, thankfully very drunk and therefore apparently senseless as to what was about to happen, was all but carried from the back of the ambulance by two military policemen, accompanied by an army chaplain. The man was so drunk that his arms did not need to be tied behind his back or his legs bound at his ankles as he made the short, stumbling walk to the stake supported by the military policemen. On arrival at the stake, and held between the two beefy redcaps, his arms were momentarily released before being tied behind it, but being drunk, he could not feel the rough surface against the skin of his wrists and hands. A further binding held his ankles to the stake. As the man drunkenly muttered to himself, a blindfold was placed over his eyes and the medical officer stepped forward to pin a small, white square of fabric over his heart.

Meanwhile, the lieutenant had loaded a single round of ammunition into each rifle with the help of an assistant provost marshal, and then mixed them up. As was usually the case, one of the rounds was a blank. When the rifles were ready, the lieutenant took up his position and signalled to the chaplain to begin saying the condemned man’s final prayer. The assistant provost marshal, by a pre-arranged and silent signal, ordered the firing squad to turn, pick up their rifles, and prepare to fire as each worked the bolts of their rifles with trembling hands. At the same time the watching companies of men were brought to attention. When the rifles were ready, the lieutenant took up his position and signalled to the chaplain to finish the condemned man’s final prayer.

The chaplain solemnly intoned ‘Amen’ and turned and walked away with his head bowed. The lieutenant then unsheathed his sword and raised it in the air. Fingers tightened on triggers and when the sword was lowered a thunderous volley rang out. Some bullets, whether deliberately or as a result of incompetence, missed the staked figure completely and threw up spurts of dust from the quarry wall behind. Some found their target and the condemned man sagged forward, at which point the medical officer approached him to determine whether life had been extinguished. With a look of disgust he signalled to the lieutenant that the man was still alive. The lieutenant, with a trembling hand, then stepped forward to finish him off with a revolver shot through the side of the head.

The watching companies were swiftly marched out of the quarry, with their sergeants silently defying them from looking anywhere but straight ahead. The firing squad was then brought to attention and marched back to its breakfast, also without a sideways glance at the dead man, followed by the lieutenant, the assistant provost marshal, the military policemen and the medical officer. They left two ambulance bearers to take down the body, which was then wrapped in a cape ready for burial, and to clear away the bloodied straw from around the stake. When they were finished, they placed the body on a stretcher and carried it to the burial site, where the chaplain presided over a short funeral service.

What you have just read is my fictional account of a British Army execution on the Western Front. It contains all the elements that you would expect, but how were these executions really organised and regulated?

† † †

It is unlikely that those who went off to the Western Front could ever have imagined the horrors they would have to face, whatever their rank or experience. The men of the British Expeditionary Force, and those who volunteered in August 1914, were naively convinced as they cheerfully marched off to war that it would be over by Christmas, while the generals, equally naively, thought that the cavalry would prevail – indeed, right up until the final days of the war, Sir Douglas Haig, the commander-in-chief, was still looking for ways to unleash his cavalry on the Germans. Nobody foresaw that this would be a more static war of trenches, mud, machine guns, barbed wire and artillery barrages.

Soldiers going to the Western Front and to the other theatres of the First World War would have been trained in the very many ways to kill the enemy using their rifles, bayonets, grenades, machine guns and artillery, yet nothing could really have prepared those men for the actual sights, sounds and conditions that they would encounter. Despite their training, throughout the war many British soldiers still could not bring themselves to shoot wounded, unarmed and retreating German soldiers, so how could that training help if they were unlucky enough to be involved as a member of a firing squad, brought together to execute one of their own? What would that have felt like? Thankfully, very few people will ever have such an experience and so we will have to use our imagination to try to understand and gain insight into that situation.

When the state decides to take the life of one of its own citizens, in what can be described as an act of judicial murder, it is a momentous judgement for all concerned. Who decided how that execution should be conducted and who should be present – or was it simply left to the individual whims and preferences of the assistant provost marshal or the commanding officers?

† † †

Those who volunteered for the army in August 1914, and those who joined afterwards, either as volunteers or as conscripts, left the civilian world behind them and found themselves in an alien environment, subject to what now seems, 100 years later, harsh military law which governed all aspects of the lives of the officers and soldiers in peace and in war, at home or overseas.

As a result of the outbreak of war, in September 1914 the normal system of military court martial was replaced by a system of summary court martial. Offences that carried the death penalty were then to be dealt with by a field general court martial presided over by a minimum of three officers, one of whom had to hold at least the rank of captain in order to act as president. All three had to be in agreement on any sentence passed. The recommended sentence was then passed up the chain of command, together with any mitigating circumstances and pleas for clemency.

The changes made in September 1914 are important because they allowed for the sentence, passed by the field general court martial, to be carried out within twenty-four hours – with no right of appeal. The reality for those sentenced to death was that the passage of time from sentence to its promulgation or announcement could be weeks if not months, whereas the time between promulgation and the actual execution was normally just a matter of a few hours.

On 8 September 1914, for example, Private Thomas Highgate at the age of 17 became the first British soldier to be executed on the Western Front for desertion, just two days after sentence had been passed, proving that the process could be quick. In fact, the time between Private Highgate being informed of the confirmation of his sentence and his execution was just forty-five minutes (David, 2013).

Driver Thomas Moore of the 24th Division Train (Army Service Corps, 4th Company) was executed on 26 February 1916, having been sentenced for murder, with his court martial having taken place on 18 February. The death sentence was only promulgated at 4.03 a.m., the company was paraded at 5.30 a.m., and just ten minutes later he was dead, which gave little time for any army chaplain to help him prepare for his end: Moore only had eighty-seven minutes from announcement to execution.

Sub-Lieutenant Edwin Dyett (opposite) was informed that the sentence of death had been passed upon him after he had returned to his battalion.

In contrast, the court martial for Sub-Lieutenant Edwin Dyett of the Nelson Battalion, Royal Naval Division, was held on 26 December 1916 for an alleged offence of desertion on 13 November (Moore, 1999). Under the Army Act, the fact that at the end of those proceedings Sub-Lieutenant Dyett was not released meant that he would have known that he had been found guilty, but at that stage he would not have been informed of the sentence, although he would have been aware of the penalty for desertion. The procedure thereafter, which had been set down in some detail, was, according to Moore:

• A character report from his company commander and an opinion as to whether the death sentence was appropriate in that case.

• A report from a medical officer as to his nervous condition.

• The commanders of the brigade, division, corps and army in which the individual’s battalion was assigned had to submit their recommendation as to whether the death sentence was necessary.

In the meantime, Dyett was returned to his battalion, where he was given the role of censoring the men’s letters. On 4 January 1917, while playing cards in the mess, he was told by an officer – in front of all those present – that a sentence of death had been confirmed by the commander-in-chief, Sir Douglas Haig. The execution took place on the 5th. It was to be a case that caused concern to many people, and was subsequently raised in Parliament.

Although Sub-Lieutenant Dyett’s case did not merit a mention in the commander-in-chief’s diaries (Sheffield and Bourne, 2005), there is an entry for 11 January 1917 that deals with eleven cases where the death penalty had been recommended. The eleven men were from the 35th Division and Haig confirmed the sentence on three of them: Lance-Sergeant William Stones and Lance-Corporals Peter Goggins and John McDonald, all from the 19th Durham Light Infantry. Where the rest were concerned, Haig commuted the sentence to fifteen years’ penal servitude, which he then suspended.

† † †

The 302 British and Commonwealth soldiers executed for military offences committed while on active service on the Western Front (Babington, 2002), cast a long shadow and their cases remain controversial to this day. As shocking as that figure might be, it represents only 10 per cent of the 3,076 sentenced to death (in fact some 20,000 offences that could have attracted the death sentence were committed over this same period). These statistics show, therefore, that some of those executed were undoubtedly unlucky to be in the wrong place at the wrong time, when those further up the command chain saw a need to make an example of them, thereby making it something of a lottery for those concerned and therefore inherently unfair. This seems to have happened in the case of the eleven men mentioned above: although all of them had been found guilty, it was the three more senior men that Haig decided needed to face the ultimate penalty. It is a pity that the records of those whose sentences were commuted were destroyed in 1924 because it would be interesting to read the reasons given and to see where their cases differed from those who were executed.

A previous diary (Sheffield and Bourne) entry, for 3 March 1915, details briefly that Haig had confirmed the death sentence on three men ‘of the Loyal North Lancs’ who had deserted, stating the reason: ‘The state of discipline in this battalion is not very satisfactory…’ This entry, and the decision it describes, raise some interesting points. Firstly, it seems to be subjective because there is no detail as to the basis of Haig’s conclusion about the state of the battalion’s discipline. A battalion’s discipline could encompass a broad spectrum of offences ranging from the soldiers’ appearance up to a reluctance to fight, and Haig’s diary entry does not clarify the shortcomings involved. Secondly, every soldier and officer in the battalion must therefore be considered to have borne a collective responsibility for the deaths of their three comrades because it is possible that, had the battalion displayed higher standards of discipline, they would have been spared, further highlighting the part that chance played in these matters.

As a final point about the number of sentences passed, it is also interesting to note that the British Army only executed thirty-seven men between 1865 and 1898 – during a time when it was fighting colonial wars all across the globe – and only four men during the whole of the Boer War from 1898 to 1902 (Irish Government Report, 2004). These statistics are important because they seem to imply that a significant increase in the prevalence of capital offences was caused by the horrors of the First World War. Although this undoubtedly played a part, it needs to be borne in mind that this was the first war for 100 years that saw the British Army fighting in Europe. This meant that, for many soldiers, home was just across the English Channel, making desertion an attractive option, whereas that would not normally have been the case if they were fighting in Africa or India. If you deserted then, where did you go?

† † †

In the early 1900s, court sentences were about punishment and deterrence, and society and the Church in general both accepted and supported capital punishment. In a civilian criminal court there could only be one sentence for the offence of murder, namely death, and once all the legal procedures were exhausted then the penalty was enacted. The situation in the military was different, and the vast majority of death sentences were passed for offences that would not be recognised as an offence in the civilian world.

With no right of appeal, the fate of the condemned man rested solely in the hands of his commander-in-chief, who would make his decision based on his view of the needs of the service rather than looking for mitigating reasons to commute the sentence. Those who did have their sentences commuted were either sent to prison or, in some cases, as a result of the Suspension of Sentences Act of 1915, the sentence would have been suspended and the individual returned to their unit with the certain knowledge that it could be enforced at any time. Where a sentence was suspended, the Act provided for the sentence to be reviewed at intervals of not more than three months, and if the individual’s conduct merited it, then the sentence could be remitted, thereby introducing the possibility of rehabilitation.

The Army (Suspension of Sentences) Act of 1915 meant that those who had their sentences commuted would serve the alternative sentence when out of the front line. This Act: ‘fulfilled the basic tenet of military law in that the penalty did nothing to precipitate a manpower shortage’.

An example of this can be found in a book by Lieutenant Max Plowman (2001) who had been a subaltern in the 10th Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment. He had served on the Western Front, and wrote that a deserter from his regiment had his death sentence commuted to two years’ hard labour, which he then served when out of the front line.

The First World War was fought in a dehumanising and brutal environment where individual life seemed increasingly to have little value except to the individual concerned and their family, friends and loved ones. Such an environment, then as now, also had the potential to lead to thoughtless actions and an emphasis on self-preservation. These, it could be argued, would also be present on the execution ground unless the procedure was regulated. So did the British Army, with its penchant for highly regulated ceremonial and an eye for detail, have in effect a ‘standard operating procedure’ to be followed for all executions, with nothing left to chance?

The Western Front from 1914 to 1918 was a world unlike any other that had gone before, or indeed came after, so there is always a potential risk of looking at it and judging it through today’s eyes rather than by the standards of those times. The risk of subjectivity could be avoided by utilising a set of regulations setting out the conduct of an execution, if they existed, thereby providing an objective means of examining the roles and experiences of those who took part against the norms of that time.

† † †

The existence of the death penalty in the military can be traced back to the fourteenth century, and was based on the twin aims of maintaining discipline and not alienating the local population, but, as mentioned above, with the important proviso that it should not cause a shortage of men. These principles of discipline and not alienating the local population can be seen in the following document that was issued to every soldier for them to keep in their Active Service Pay Book (The National Archives, WO 95/1553/1):

You are ordered abroad as a soldier of the King to help our French comrades against the invasion of a common enemy. You have to perform a task which will need your courage, your energy, your patience. Remember that the honour of the British Army depends on your individual conduct. It will be your duty not only to set an example of discipline and perfect steadiness under fire but also to maintain the most friendly relations with those whom you are helping in this struggle. The operations in which you are engaged will, for the most part, take place in a friendly country, and you can do your own country no better service than in showing yourself in France and Belgium in the true character of a British soldier.

Be invariably courteous, considerate and kind. Never do anything likely to injure or destroy property, and always look upon looting as a disgraceful act. You are sure to be met with a welcome and be trusted; your conduct must justify that welcome and that trust. Your duty cannot be done unless your health is sound. So keep constantly on your guard against any excesses. In this new experience you may find temptations in wine and women. You must entirely resist both temptations, and, while treating all women with perfect courtesy, you should avoid any intimacy.

Do your duty bravely.

Fear God.

Honour the King

Kitchener

Field Marshal

This paper was then supplemented by a further exhortation from the brigade to which the men were attached, in this case the 13th Brigade (WO 95/1553/1):

We shall shortly, probably, be engaged with the enemy.

Remember that the Germans hate the bayonet, and also that their theory that ‘determined men in sufficient numbers can do anything’ has already been proved, at Liege, to be a fallacy. In the face of modern weapons they cannot.

Remember also that heavy artillery fire looks terrible, but is far more alarming than harmful, and if you do not bunch, it will not do much damage. The Germans do bunch, hence their enormous losses.

Therefore remember three things:

1. If stationary, keep cool and shoot straight and steadily.

2. If moving, keep good intervals and distances.

3. If the opportunity offers, use the bayonet with all the vigour you can.

And, above all, remember that no man in the 13th Brigade surrenders. We must fight to the end, for the honour of our Country, and the credit of our Brigade and our Regiments.

If these words came from the mouth of General Melchett in Blackadder Goes Forth, they would, at the very least, raise a smile from an audience today because of this document’s seemingly comedic content. However, its author was deadly serious with the exhortation that ‘no man in the 13th Brigade surrenders’. It is likely that it was this exhortation that sealed the fate of Private Thomas Highgate.

† † †

The Army Act, which was first introduced in 1881, was updated every year thereafter and passed as the Army (Annual) Act by Parliament, thereby enabling the government to maintain a standing army. The Army Act of 1881 formed part of the law of England, with one difference being that it was administered by military officers and court, and emphasised that ‘in all times and in all places, the conduct of officers and soldiers as such is regulated by military law.’