Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

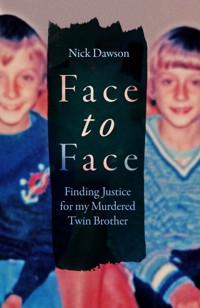

When his identical twin brother Simon was kicked to death, all Nick Dawson felt for the killers was hatred. Struggling in a world where his mirror image had vanished, he came to realise there was only one way to stop the torture - acceptance. Travelling to the absolute limits of personal darkness, Nick came face to face with his brother's killers. Now a champion of restorative justice, Nick heads behind bars, asking hardened criminals to change, to think of their victims, to make amends. In Face To Face he takes us with him on a journey into this hidden and unpredictable world.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 287

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Published in the UK and USA in 2025 byIcon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP email: [email protected]

ISBN: 978-183773-242-5ebook: 978-183773-244-9

Text copyright © 2025 Nick Dawson

The author has asserted his moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Typeset by SJmagic DESIGN SERVICES, India

Printed and bound in Great Britain

Appointed GPSR EU Representative:Easy Access System Europe Oü, 16879218Address: Mustamäe tee 50, 10621, Tallinn, EstoniaContact Details: [email protected], +358 40 500 3575

For Jules,Forever by my side, living this journey together x

CONTENTS

Prologue

1Eye to Eye

2Twins

3Murder

4Manhunt

5Killers

6Numb

7Collapse

8Ripples

9Face to Face

10Prison

11Connections

12Acceptance

Conclusion

Acknowledgements

PROLOGUE

For a long time, I thought this story had only one end. My twin brother gone, and me left wandering a desert of sorrow, anger and despair.

Simon was my identical twin. We looked the same, sounded the same, moved the same. When we looked in a mirror, I looked at him and he looked at me. And then one day the mirror shattered. Simon was murdered. He was beaten, robbed and thrown in a pond to drown. The reflection in the mirror was gone. Instead all I saw was brutality and ugliness.

When the world turns grey, colour becomes impossible to imagine, as if it never existed. Over time, as you rebuild, a few faint pastel shades start to appear, and then something a little more vivid. The palette slowly returns. Eventually, you can paint a picture. Actually, two pictures. One of what you lost, and one of what you have now. And that is what I am doing here, honestly, accurately and with Simon at their centre. In both these paintings Simon is alive. That’s how he feels to me, and, by telling you about him here, that’s how I want him to feel to you. I refuse to portray my beautiful twin brother in charcoal shades when to everyone he met he was, and is, a rainbow.

I’ll be honest. There have been times when my view of that rainbow has been obscured. That’s what happens when you look at life through a cloud of hatred and rage. It took me a while to understand that to find something resembling inner peace I might need to open my mind to a different way of thinking. That realisation came in the most unlikely of settings. I wasn’t on a psychiatrist’s sofa, or meditating in a mountain hideaway; I was in a prison sitting opposite Craig, one of Simon’s murderers.

From the exact moment of Simon’s death, Craig and I had both been travelling our own very different paths. Initially, they had diverged wildly. I was a lone twin. He was a killer. But we did have one thing in common. We were both serving life sentences. And it was that which would eventually create a desire in us both for our paths to cross.

Restorative justice, the idea that both the perpetrator of a crime and a victim can benefit from meeting one another, was the medium that would bring us together. It was a remarkable transformation. For many years, the only reason I wanted to be near to Craig was to kill him. Now we were sitting a matter of a few feet from one another, talking. Together, we unpacked the horrific events that led to Simon’s death. I revealed the long-lasting and catastrophic effects of the murder. He talked about his own life and how, on release, he hoped, in some small way, to try to make amends. If you think this was a moment of great personal liberation for me, celebration even, you’d be wrong. It could never have been that. The meeting was incredibly hard. There were times when I believed myself to be incredibly disloyal. I felt Simon looking down from above, wondering how I could possibly talk to his murderer. But at the same time, I knew Craig was no longer the evil monster I remembered from court sixteen years previously. A second chance wasn’t undeserved.

Since that time, as an advocate of restorative justice, I have spent many hours in UK prisons. I have met hundreds of criminals, many of them violent, despicably so. I have looked them in the eye and told them my story – Simon’s story – in the hope that they, too, will understand the impact of their crimes. Hopefully, they will go on to live a different kind of life. Perhaps even consider restorative justice themselves. More recently I have even become a prison visitor, a voluntary role ensuring that the conditions inmates live in are decent and that they receive the help they need. I totally understand how this appears to run completely counter to my experience. As someone who lost his twin to the most awful of crimes, why would I ever want to help those who so disrespect civilised society? But if we don’t step onto the other side of the tracks, how can we ever hope to understand those who dwell there? How can we help them not to make the same mistakes again and again? How can we stop other people hurting like I am? Prisoners are, like it or not, human beings like the rest of us.

There is, though, one thing I’d like to make clear. Forgiveness is a line I have yet fully to cross. Where Simon was once my companion, now I have emptiness. And I am far from alone. My family have all suffered intensely down the years, not only through the pain of loss, but through breakdown and mental illness. For all of us, demons lurk around every corner.

It doesn’t stop there. In the course of writing this book, I vowed to explore just how far the ripples of Simon’s murder extend. To hear the stories of Simon’s friends, their lives turned upside down, their guilt, their disintegration, has been as upsetting as it’s been illuminating. Those ripples will, sadly, continue for many decades, potentially on through the generations – something I have seen with my own children.

More positively, meeting so many incredible people who knew and loved Simon has also filled me up, in a way that for so long seemed unimaginable. While sometimes difficult to hear, their words have allowed me to better understand the person he was when he died. Lack of information is a torture for those who lose loved ones in tragic situations. Death is a jigsaw thrown on the floor. I thank them sincerely for helping me rebuild my brother’s life. I needed to touch him, feel him, capture the memories before it’s too late.

Whatever the circumstances of someone’s passing, it’s incumbent on those left behind to ensure they’re remembered. In the weeks following Simon’s death, I found a letter I wrote to Mum and Dad. Looking at it now reminds me why I have written this book. ‘Maintaining Simon’s memory is the most important thing,’ I tell them. And it’s true.

There was something else I wanted my parents to know – ‘Simon’s heart and soul lives on in me.’ As Simon’s identical twin, I’ve always felt I speak for him. His voice was taken away in such a cruel and heartless way. This book is a way not just for me, but for Simon to tell his story. For Simon to be heard. For Simon to be at peace.

Simon is dead. He was murdered by two attackers in the early hours of 29 August 1998. But he lives on in me. And now he lives on in this book.

Face to face again. At last.

1. EYE TO EYE

It was the first prison I had ever set foot in and my preconceptions were depressingly accurate. Cold and clinical. Constant jangling of keys. Incessant locking and unlocking, the thud of each door matching that of my heart as we were led to a waiting room – Mum, Dad and me, all determined to be there for Simon, to face his killer, and have our say. The sound of our pain, never-ending, would finally be heard, something I felt particularly keenly as Simon’s identical twin.

The Probation Service had kept our family informed as Craig and his co-murderer passed through the prison system. Eventually, in 2012, we were told we’d be able to attend their parole hearings and read out victim impact statements, personal reflections on how the murder had affected us over the years. There was never any doubt in my mind – I would do it. Right from the off, I wanted to be part of the process. Preparing and reading a statement provided a sense of purpose, of involvement, in a scenario from which I, and therefore Simon, had been separate for so long. Simon was my twin and I wanted him to be heard. My voice is his voice and always will be.

But, if I’m honest with myself, there was another element to attending the hearing. I was genuinely curious to see what Simon’s killers, Craig Roberts and Carl Harrison, were like after all this time. More than a decade had passed since the murder. Craig, in particular, intrigued me. He was sixteen, little more than a kid really, when he killed Simon, when he beat and kicked him to a pulp and threw him unconscious into a pond. Now he’d be a man. What did he look like? And how would he react to seeing Simon’s identical twin, face to face? Would he be ashamed? Emotional? Detached? What would he be? So many questions. So much curiosity. I craved the contact that would bring the answers. I had a definite and deep desire to connect; to meet the two men who had so cruelly taken away my twin brother’s life. Could they look me, a living, breathing version of Simon, in the eye and take in what I’d say to them? Were they monsters still? Would there be even an ounce of humanity in them?

I readied my statement with several weeks to go, discussing all kinds of feelings and thoughts with my wife Jules. She had travelled with me every step of this torturous journey, from the exact second I found out that Simon had been murdered, through press appeals where she had sat close and clutched my hand, on to the arrests and trial, and into an often deeply challenging aftermath.

While I was keen to be listened to, I was under no illusion that the hearing was not going to be anything other than a hugely difficult and deeply affecting experience. This wasn’t a matter of getting up one day, taking a leisurely drive to a prison, wandering into a room, sitting down and saying a few words to a stranger. I wanted to tell this man, this murderer – HIM – in unsparing detail about the wonderful brother he had so senselessly taken away and the ugly burden of hurt with which he had replaced him. Every sentence, every description, every emotion mattered. These weren’t sentences on a piece of paper; they were barbs buried deep in the skin of myself and my family. And we had carried them for years. I wanted my statement, my delivery, my demeanour to stand up to the extreme emotional rigour of the exercise. I had to make sure I was mentally ready.

The day came. Mum, Dad and I would all be giving statements to the parole board. It was an odd situation. A desire for the whole thing to be over mixed with a wish for it never to start. But it had to be done. We wanted, needed, it to be done, for Simon and for us. I felt immensely proud of Mum and Dad. They were going to the very depths of their emotions to ensure Simon’s voice was heard. That is true strength, so, so far removed from the cowardice of the murderous attack that had taken their son.

We stood, paced, shuffled – so much nervous energy – in that waiting room for what seemed like an eternity. Time is one thing nobody’s short of in prison. Eventually, a warder entered. Who was going first? So swept up were we in the emotion of the day that we’d never given such a basic element of the exercise a second thought. Instinctively, Dad got up. By now he was in his mid-seventies and becoming increasingly frail, but it would take a lot more than age and a few aches and pains to prevent him taking the lead and saying his piece for his son. The three of us stood and hugged.

‘Good luck!’ I had to say something.

Mum and I watched him exit the room, accompanied by the officer. We sat and looked at our feet. Some minutes later he returned. We barely exchanged words. We didn’t need to. The tears welling in his eyes, the choked expression, the sadness said everything. Just the briefest of nods. ‘I’m OK.’ He had to say something.

Mum was next. I could barely imagine what she was thinking as she was taken to a seat opposite one of the two men who had stamped on her son’s head before leaving him to drown. I had no idea what she was going to say. Each of us was very private about our statements. They hadn’t been shared. We respected one another’s need for the procedure to be personal. Something we were doing for Simon, yes, but for ourselves, too.

Mum returned. She’d aged ten years in fifteen minutes. Again, a glance. An acknowledgement of something that had had to be done. And then it was me. I was walked along a long blank corridor by the prison officer, a million thoughts ricocheting off the walls – how Craig might react, how I might react, how desperately I wanted to get my words out without collapsing into tears and breaking down. My legs were jelly by the time I reached the small flight of stairs that led to the meeting room, to the extent that I could barely manage to climb them. The officer noticed my struggle. ‘Would you like to sit down for a minute before going in?’ It wasn’t an option. I’d come this far. ‘No.’ I just needed to get in there. I was ready. The warder opened the door and I walked in.

I didn’t need a second look. It was unmistakably him. When you’ve spent hours staring at someone in a courtroom, someone who has violated your family in the most stark and shocking manner, you don’t forget. Craig might not have been a kid anymore. Indeed, he was a man in his thirties. But his features – the shape of his face, those eyes – were easily recognisable.

Adrenalin surged through me as I was beckoned to take a seat. In front of me was the parole board chair and two members. Craig, in classic prison attire – T-shirt, tracksuit bottoms and trainers – was flanked by his parole officer and solicitor. I could see straight away he was in tears, shaken no doubt by the sight of Mum and Dad and what they had told him. I could imagine in particular the emotional power of my mum’s statement. Its thudding impact.

There was only one thing I wanted to do – tell my story. I could feel inside me a pressure wanting release. Anger, upset, grief – a huge need to cry. I drew a deep breath and told myself this was about being strong, representing Simon, empowering him. I felt deeply that Simon wanted to speak from inside me. I became aware of the parole chair talking, no doubt delivering the same preamble my mum and dad had been given. White noise. Nothing more. I didn’t care what she was saying. I just wanted it to end so I could say my piece. And then it came – the silence. I looked Craig straight in the eye and began.

It is very hard to describe the impact of the brutal murder of your twin brother to someone outside your family. Words read out by an advocate, I feel, really don’t portray the pain and hurt that the victim’s family go through. That’s why, as Simon’s identical twin brother, I had to come to the hearing today, out of a sense of purpose for Simon, my mum, my dad and my brother Richard. And to try and portray the permanent hurt inside my family.

The murder of a loved one is so very, very hard to bear. For me, as Simon’s identical twin, it has been especially hard so far, and painful in many unique ways. I’ll never forget seeing him in the mortuary on that pouring wet day in early September 1998 – he was lying there, black, blue, massive black eyes, cuts all over him, freezing cold and hard as a board. It was Simon, my dead, badly beaten-up twin brother. It was like looking at myself dead, it really was.

I looked up. Craig was staring straight at me. I carried on.

Simon’s murder took a huge ‘chunk’ out of me. I am a changed personality in many ways, some of which I don’t actually realise myself. I am more withdrawn, more insular, and much less confident as a person generally. I have flashes of rage born out of anger towards the two people who killed my brother.

Simon’s murder continues to have an impact every day of every week. His death profoundly impacted my marriage and my relationship with my wife. We had only been married six months when Simon was murdered, and hence it had such a devastating impact so early on in our relationship. Our marriage has survived but continues to be impacted. Although we have two lovely children now, Simon’s death is always in the ‘air’, and now my children are growing up they want to know about what happened to the uncle they were never able to meet. How do I explain the senseless murder of my twin brother to my children?

I think of Simon’s death every single day. I dream about his loss frequently. I continue to receive counselling. I often visualise the beating that he took that night in my mind until I cry. A murder is a bereavement that is so very hard to move on from. I often describe it as a brutal ugly cloud that drags along with you wherever you are, exercising its demons and reminders just whenever it decides to.

The potential release of Craig Roberts, coming on top of Carl Harrison at the same time, is another massive hurdle that the family needs to face. It will be painful knowing that they have a chance to rebuild their lives again, to see family and friends, and to enjoy living a normal existence.

I still have a great sense of anger towards both prisoners for what they did to Simon on that night. I know that this anger will never subside. I would never, ever accept an apology or any kind of message from either of the prisoners.

The release is a devastating prospect in every sense. I’ll need to be particularly supportive of my mum and dad, who I know will suffer particularly badly around the time of release.

I don’t really yet fully know how I feel about the whole release, certainly tremendous anger and bitterness that they have a life to rebuild, while my brother looks down from heaven – crying at the life he has lost.

I had always imagined Craig’s face as that of a murdering evil monster. I had also suspected a slightly cynical, clinical even, edge to him. Although he was the younger of the two killers, we always perceived him, from what we saw and heard in court, as the more intelligent and felt he was the ringleader. Now, however, as I saw his reaction to my revelation of the desperate and everlasting grief he had caused, it was as if a veil was being lifted. There, instead of a thing of savagery, I saw a person, someone who was deeply ashamed of what he’d done.

A parole hearing doesn’t allow an offender to speak to a victim or their relatives, but, while Craig may not have been allowed to talk, seeing the remorse etched on his face made me think he was beginning to understand the true extent of what he’d done. It seemed like he no longer wished to live a life in blinkers, as if avoidance, hiding from reality, would eat him alive and stop him moving on. If there was to be a second chapter to his life, then the narrative had to be penned by his own guiding hand. At that moment, in that prison, that narrative was one of a grown man trying to recover from the person he used to be. Where I had always imagined a beast who should never be released, here was someone different, someone who had sat and listened in a respectful way. I walked out of the prison that day with an odd and unexpected feeling of achievement, a contentment that we had shown courage in attending the hearing, that we had been in control, able to see the offender and read our statements. I realised then that what I really wanted, needed even, was for this to be more than a one-way process. I had a connection with Craig. I wanted to meet him. I was ready to talk.

What I didn’t know was that Craig was on his own journey to exactly the same conclusion. In prison, he’d heard a talk by the father of a murder victim about restorative justice, where those who have suffered from criminal activity have the chance of discourse with the perpetrator. The impact of the talk had been significant, to the extent that he followed it up by putting in a request for his own victim’s family to meet with him. It was a natural progression – in prison he’d studied courses which had introduced him to the concept of social justice.

The core dynamic of restorative justice is that it comes from both sides – a synchronisation of a desire to address the past. Relatives may attend parole hearings, as we had, and maybe even find some satisfaction, but the prisoner’s silence is deafening. You read out a statement and that’s the end of the process. The inmate has no opportunity to verbalise their own regret or sorrow. If there is contrition, it cannot be spoken. Parole hearings wholly ignore, for both sides, the healing power of conversation. Restorative justice, on the other hand, allows for exactly that scenario, but is a system rarely used, especially in a case like mine where what’s being addressed is a crime of murder. In fact, in all the time the prisoners had been in jail, I’d never heard of restorative justice. I get why. Violent death is raw, and forever continues to be. ‘Would you like to meet the offender?’ isn’t a question many relatives of murder victims have any desire to be asked. But in my head I felt ready to talk to Craig. Forgiveness wasn’t in my mind. The journey I was on was one of acceptance, and talking to Craig would have to happen if ever I was to reach that stage.

There was another element, however unpalatable, that had been nudging its way forward in my mind. As Craig and his co-killer Carl began the procedure of being moved towards release, I was being forced more and more to wrestle with the question of whether they deserved a second chance. Potential freedom for my brother’s killers was extremely hard to reconcile. How could they be allowed a possible return to normal life when our wounds remained so open, so deep? And yet, maybe, despite my instincts, forged in the cauldron of bleak experience – Craig had been released from a custodial sentence the same day he took Simon’s life – it could be that anyone can make a serious mistake and be given a new start. Even murderers. Even the murderers of my twin brother. I’d always thought I wanted something positive to come out of Simon’s death. Perhaps Craig could be a starting point. Perhaps he could be someone whose reflections on his past might seep into the consciences of others like him and prevent more families going through what we’d been through. Even if that was just one family spared our horror, it would be a success. Strange to think that I’d gone from a hate-fuelled desire never to see Craig released to a recognition that maybe there was another way. But I could not deny I was ready to talk to him.

My victim liaison officer, Stella, called to let me know of Craig’s request. Not that I was going to rush into anything. I did have some caution. For every part of me that wanted to connect with Craig, another part was nervous. I knew from experience how easily revisiting the attack could upset me, make me angry. It still does and, I suspect, always will. Recently, I sat down with my daughter Keira and watched a video of my and Jules’ wedding, taken by a guest with a camcorder. I had never seen it before and wanted to recall various elements of the day, but more than anything to see moving images of Simon. I was deeply distressed, able to internalise the pain while my daughter was there, but the tears came afterwards, for the same reason I am so often overcome – the sheer unfairness of it all.

I can be overwhelmed by tears very easily if I let myself. It happens when I look at newspaper cuttings surrounding Simon’s death – particularly upsetting, especially the details of the murder itself. Not just the violence. The element of taking advantage of a misplaced trust – Simon, confused after leaving a nightclub in an unfamiliar area, had simply asked two people if they could help him find his way to a friend’s house – sickens me. Naively, he looked at those young men as two people who could give him a hand. They looked at him as someone they could assault, rob and, ultimately, kill. Simon was like that – unquestioning, happy go lucky. And where, ultimately, did that get him?

Any dip into the past is likely to make me remember things I have forgotten. A newspaper report is an impersonal matter to most people, a factual report. You’re meant to read it, flip the page and go on to something else. When it concerns yourself you are unable to do anything so simple. You are reading it in stereo. In one sense it’s a factual account of something that has happened. In another you are heavily entwined in every paragraph, every sentence, every word. One report I found not long ago told how Simon, according to Carl, had become increasingly concerned for his own safety – ‘getting paranoid’ as Carl put it. At one point, Simon had crouched down, possibly to sort his laces out, which was when the attack was launched. The report stated that Carl punched him on the chin and then started putting the boot in. Simon went to grab Carl’s legs, which was when Craig also dived in, kicking him. I had never read that detail before and it had me imagining all sorts of things about Simon struggling on the ground, trying to protect himself.

Another report detailed evidence from the pathologist, describing Simon’s injuries and the nature of the attack – ‘short, sharp, and brutal’ – most likely to have caused them. It revealed that Simon was, at best, semi-conscious when Craig and Carl threw him in the pond after subjecting him to a totally unnecessary frenzy of violence. I recall the pathologist’s evidence at the trial only too easily. As he described the trauma from sustained kicks and blows to Simon’s head, my mum had run from the courtroom.

Before I could truly accept a move towards restorative justice, I wanted to fully understand what it entailed, what it might do to me and, by extension, those around me. How would Mum and Dad react if I told them I was meeting Craig? Might the emotional pressure affect my mood, my demeanour, at home? Could it wreck the equilibrium I had battled so hard to build? And then there was Simon. I felt disloyal to him. What would he think if he saw me doing this? Sitting down to chat with one of his killers – a person who had inflicted such violence upon him and left him for dead. These were huge matters which had to be reconciled in my mind. I talked it all over with Jules. My parents, meanwhile, assured me that while restorative justice was never something they could countenance, they were OK with me accessing it. Eventually, after many months of debate and counter-debate, I made my decision.

The session was meticulously planned. We had two restorative justice facilitators, Mandy and Jenny, from the Victim Support organisation. They came to my house and we had six meetings, a series of preparation exercises, over several months. The idea was to explore what I wanted to get out of the ‘conference’, as a restorative justice meeting is called. What was I hoping for? Why now? And would I be able to deal with the consequences? There was, for example, every possibility I would come out of the conference having heard things that were deeply upsetting. Some of what unravelled I would likely not be able to share with my parents because it would simply be too distressing. Having made me ask serious questions of myself, they then liaised with Craig in prison. Why did he want to do this? What questions did he want to ask? How would he react if I asked certain questions of him? There’s a loose framework of questions in a conference but I was far from beholden to sticking to it.

Eventually, after a year of planning and preparation, and with the reasons for going ahead with restorative justice settled in my mind (and presumably Craig’s), the session was confirmed. Even then, however, after all the meetings and explanations, the late nights talking it through with Jules, there was a big part of me that felt totally lost as to what was to come. What would it really be like in that room opposite the man who had murdered my brother? I was fortunate then to meet Ray Donovan, who had been through restorative justice with the three killers of his son Christopher, again a mindless attack on an innocent young man. A week before his nineteenth birthday, Christopher was kicked unconscious in the street after being set upon by nine thugs. Left unconscious in the middle of a four-lane road, he was then hit by a car and dragged forty feet. Ray, who, along with his wife Vi, has shown immense mental fortitude and is someone I deeply admire, became a mentor to me. Having the support of a person who understood what I was about to go through was incredibly valuable. Ray talked about what to do and what not to do in the meeting. More pertinently, he reinforced something I already knew – it would be a very powerful and emotional day.

With a date set, Jules and I drove to the jail, HMP Woodhill, near Milton Keynes. Craig’s environment. It’s another, albeit inevitable, oddity of the justice system that the victims are the ones constantly asked to step into alien and deeply unsettling surroundings. My nerves had been on edge from the minute I woke that morning, not improved any when I reached the gates of the high-security facility only to find they didn’t have me down as being a visitor. The mix-up sorted, Mandy took me through to the meeting place, the chapel, an eerie setting made even more so by the nature of what was about to happen. She showed me the set-up, essentially a circle of chairs, close, no physical barrier. To one side was a small screened-off area in case I needed time out. Everything had been designed to be as natural, as comfortable, as possible, but the way a few chairs were set out could never disguise the weight of what was about to happen. In that moment, I was very nearly overcome. I walked round the circle and started to cry. I seriously questioned whether this was this the right thing to do, a thought which had come and gone a few times in the past few months. I could have pulled out at any stage if I’d had a wobble, and those doubts did rise to the surface on occasions. In fact, the initial date for my meeting with Craig had been two months earlier.

I convinced myself again that this was the right thing to do. I had travelled too far down this track to walk away at the last hurdle. Mandy and Jenny sat down beside me and Jules, and Mandy asked if I was ready. With tears again welling up, I signalled that I was good to go.

Craig walked in.

Where once had been a sixteen-year-old kid, now there was a man, well-built, muscular, with a strong, filled-out face. Flanked by his probation officer and a prison warder, he took his place. And so here he was, one of the two killers who had brought a savage end to the life of a young man adored by all he met. Except for those two of course. They had snuffed out Simon’s life, his light, for a watch and a bank card. They had stamped on his head with both feet, beaten him unconscious and laughed as they poured water over him to bring him round to get his pin number. Their snarling, twisted faces, distorted in a frenzy of drink and drug-fuelled violence, was the last example of ‘humanity’ Simon ever saw. Craig and Carl beat him up and killed him. He died with that rank vicious cruelty imprinted, quite literally, on his brain.

While I had seen a different, better, side to Craig in the parole meetings, I still carried those images with me. They weren’t going to disappear into the ether now. Craig had always been portrayed in the media as being at the forefront of the assault, always in denial, always trying to get off. At that time, he was simply a nasty individual. According to newspaper reports he had actually been wearing Simon’s watch when he was arrested. No matter how much I tried to neutralise my feelings I would never be able to comprehend how someone could look at something so personal, torn from the wrist of the person they’ve just violently murdered, and coldly and calculatedly attach it to themselves. Even with the distance of time it’s something that always makes me very angry.

At the trial I had actually harboured fantasies of revenge. You know the scene from Reservoir Dogs where a man is tied to a chair and his tormentor cuts off his ears? I honestly had the same thoughts about Craig and Carl. I used to dream about torturing them, inflicting pain on them, and eventually killing them. I went through levels of anger that I never knew I was capable of. ‘If I get my hands on them,’ I would say, ‘I will kill them.’ And now here was one of them sat not five feet away from me. I had requested his presence, as he had requested mine.