28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Knitwear is a highly influential, though sometimes overlooked, element of contemporary fashion. It's simple yet amazingly versatile textile structure offers endless possibilities for exploration. To develop a successful collection the knitwear designer must design both fabric and garment, employing a range of creative and technical skills. Written for fashion, textile and knitwear design students and young professional designers, Fashion Knitwear Design provides advice on the diverse skills needed to take a knitwear design from initial idea to finished product. It provides advice on key knitwear design skills; insights into today's global industry; explanations of structures, machines and yarn types, and a history of fashion knitwear design and technology. It is superbly illustrated with 173 colour photographs and 53 line artworks. Fashion Knitwear Design is written by a team of specialists who deliver Nottingham Trent University's highly respected fashion knitwear design courses, including the only undergraduate degree within the UK to focus solely on the subject.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 312

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

FASHION KNITWEAR DESIGN

Edited byAmy Twigger Holroyd and Helen Hill

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2019 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2019

© 2019 Amy Twigger Holroyd and Helen Hill, editorial and selection matter; individual chapters, the contributors

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 570 1

Frontispiece: Knitwear is a huge part of contemporary fashion, equally at home on the catwalk and within our wardrobes.

DESIGNER: VERITY MILLER. PHOTOGRAPHER: DAVID BAIRD FOR NOTTINGHAM TRENT UNIVERSITY

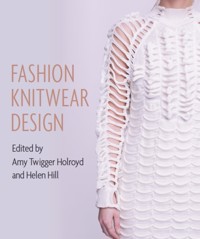

Front cover: DESIGNER: JACARANDA BRAIN. PHOTOGRAPHERS: EMILY DRINKELD/HAO FU

Back cover, left: DESIGNER: KATE BAILEY. PHOTOGRAPHER: SOPHIE DIONNE PYKE

Back cover, right: PHOTOGRAPHER: RASHA KOTAICHE

CONTENTS

Introduction (Amy Twigger Holroyd)

1 History and Context (Cathy Challender)

2 Research (Claire Preskey)

3 Yarns (Kandy Diamond)

4 Technology and Structures (Will Hurley)

5 Design and Communication (Jane Thomson)

6 Pattern Cutting and Silhouette (Juliana Sissons)

7 Construction and Manufacturing (Helen Hill)

8 Careers (Ian McInnes)

About the Authors

Acknowledgements

Websites and Further Reading

Index

INTRODUCTION

by Amy Twigger Holroyd

Take a look at what you are wearing today. Would you believe me if I told you that much of your outfit is knitted? There are, of course, the quintessential knitwear items: sweaters, cardigans, socks. But what about your underwear, your T-shirt, your sportswear? Although it might not be immediately obvious, the fabrics used for these items are also knitted. They share the same basic structure as that of a hand-knitted sweater, though they are produced on sophisticated industrial machines and at a much smaller scale. You might even be wearing knitted shoes: a recent innovation that exploits the knitted structure’s unique capacity for three-dimensional shaping. Knitwear, then, is a huge part of contemporary fashion. What may initially seem to be a rather obscure specialism is actually a huge global industry, generating the garments that populate every rail, shelf and drawer of our wardrobes.

Knitting offers endless possibilities for design. This fabric, with three-dimensional qualities, knitted in organic cotton by designer Yena Moon, was created through the simple yet ingenious placement of knit and purl stitches.

In terms of design, knitwear is a challenging and distinctive discipline, which blends the skills of the fashion designer with those of the textile designer. When we create knitwear, we design fabric and garment in one. Silhouette, texture, colour, pattern, construction, detailing: all are under the creative control of the designer. Exploring these various dimensions of design provides ample scope for the creation of innovative fashion outcomes, whether flamboyant catwalk statements in eye-popping colour combinations or understated and elegant garments that are intended to be worn for a lifetime.

The knitted structure that we manipulate to produce our designs has unique characteristics in terms of stretch and shaping. These qualities are perhaps most apparent in the case of seamless knitwear: three-dimensional garments formed through the process of knitting, without the need for conventional seams. But they are also exploited in garments made by using the more familiar construction processes of fully fashioned knitwear, in which garment panels are knitted to shape, and cut-and-sew production, in which pieces are cut from knitted fabric.

Whatever the case, the knitwear designer is working with a simple yet amazingly versatile structure, with endless possibilities for creative exploration. Knitted fabrics can have highly diverse visual, physical and tactile properties. They can be produced by using centuries-old craft techniques or state-of-the-art digital technologies. They provide the opportunity to connect with culturally significant traditions, even while pushing technical boundaries. The discipline, therefore, offers incredible scope for experimentation and the development of a unique approach to design.

Making the most of these possibilities demands a combination of creative insight and technical knowledge; the two are intertwined. In fact, researchers at the Open University who studied knitwear designers at work found that technical constraints had to be considered from the earliest stages of the design process. Another study found that knitwear design shares characteristics with both fashion design and engineering. Just like the fashion designer, the knitwear designer must be able to develop an original creative concept, generate garment ideas and resolve these ideas into workable designs by using their own in-depth understanding of the industry, the wearer and emerging trends. But, like the engineer, they must initiate and shape their ideas by using a deep awareness of how the designs might be produced, bearing in mind the distinctive capacities and limitations of the knitted structure. It is no wonder that the skills of the knitwear designer are in high demand.

Fig. 0.1 With this outfit, designer Kate Bailey has elegantly integrated metal components into a fine-gauge knitted fabric, challenging established perceptions of knitwear. PHOTOGRAPHER: SOPHIE DIONNE PYKE

Fig. 0.2 A classic men’s knitwear shape can be reinvented for a contemporary fashion context through the inclusion of intricate integral patterning. DESIGNER: HELEN KAYE. PHOTOGRAPHER: JAMIE GORDON

About the book

This book has been written by the team of specialists who deliver Nottingham Trent University’s undergraduate and postgraduate courses in fashion knitwear design. BA (Hons) Fashion Knitwear Design and Knitted Textiles is the only undergraduate course delivered within the UK to focus solely on fashion knitwear design, while the MA in Fashion Knitwear Design supports students to further develop their creative and technical expertise. With decades of experience in teaching fashion knitwear design, the university has an international reputation for excellence and an impressive roll call of alumni working internationally in all areas of the industry.

The nine authors have extensive and varied experience of professional knitwear design, encompassing design studios, manufacturing environments and trend-forecasting agencies; mass-market companies, designer labels and micro-scale businesses; and groundbreaking academic research. We have designed a diverse range of outcomes including knitted fabric swatches, knitwear collections, one-off items, shoes and non-wearable art pieces and have specialist interests including archives, sustainable design and innovative computer-aided design and manufacturing (CAD/CAM).

This expertise is captured within the eight chapters of the book, which take in the entire knitwear design process, along with the history of the industry and potential career routes. While each author has written about an area of particular interest, there are many threads that run across the book as a whole, and the content has been developed through discussion and collaborative reflection. As we have written the book, we have adopted an inclusive approach that covers a range of contexts, from micro-scale businesses to mass production and from student projects to professional practice. Whatever your place within the industry, you will benefit from a well-developed understanding of the way in which the industry operates and the diverse processes involved in taking a knitwear design from initial idea to finished product.

Fig. 0.3 The vast majority of knitwear is produced in a factory environment, such as that of the Jack Masters industrial knitting plant in Leicester. COURTESY: JACK MASTERS LTD

Fig. 0.4 Alternative contexts for knitwear production include small studios, where domestic and hand-flat knitting machines are often used.

Chapter by chapter

Chapter 1, by Cathy Challender, explores the history of knitting and knitwear, providing an overview of the developments that have led to today’s dynamic industry. It explores the early beginnings of the craft, from medieval hand knitting to the invention of the stocking frame and the technological innovations that transformed the possibilities of knitting during the Industrial Revolution. The major shifts in knitwear styles and production contexts that occurred throughout the twentieth century and into the current era are discussed, along with a history of knitting as a hobby activity.

Chapter 2, by Claire Preskey, focuses on the research that drives any design project. Starting with a discussion of the design brief that kick-starts the process, it then explores key avenues of research. Market research involves studying existing ranges, brand identities and consumer profiles, while trend research requires the designer to pick up on emerging cultural shifts. The designer also needs to gather personal inspiration to develop a unique concept from which to design. The chapter concludes with advice on how to communicate this research in a professional manner.

Chapter 3, by Kandy Diamond, provides an introduction to the knitwear designer’s raw material: yarn. It explores various natural, synthetic and regenerated fibres, explaining the link between their characteristics at a microscopic level and the properties of the knitwear that they are used to produce. The processes involved in turning these fibres into yarn are outlined, while a user-friendly guide demystifies yarn counts and types. The final section provides guidance to the designer on how to select yarns, weighing up a range of aesthetic, technological and practical factors.

Chapter 4, by Will Hurley, supports the designer to develop their knowledge of knitted structures and the technologies that are used to produce them. The key principles of weft and warp knitting are discussed, and an outline of the diverse range of knitting machines in use today is presented. An introduction to the basics of weft-knitted structures is followed by profiles of various single- and double-jersey fabrics, considering both the construction and the application of these fabrics in fashion contexts. To conclude, the chapter discusses the translation of designs by using digital industrial technologies.

Chapter 5, by Jane Thomson, investigates the development and communication of original knitwear designs. Picking up from Chapter 3, it discusses ways of responding to the material gathered during the research process in order to generate design ideas. Two sections then explore the central creative process of the knitwear designer: developing these ideas into coherent collections of knitted fabrics and knitted garments through drawing, sampling and working in three dimensions. A final section focuses on the communication of designs via fashion illustrations, garment flats and design boards.

Chapter 6, by Juliana Sissons, guides the designer through the process of creating a three-dimensional knitwear silhouette by using a range of approaches to pattern cutting. It describes the steps involved in flat-pattern cutting, creating and adapting basic blocks to generate two-dimensional pattern pieces. It then explains how to generate instructions, to guide the knitting of these pieces, including the calculation of the shapings required for fully fashioned construction. Alternative approaches to silhouette creation are discussed, including draping jersey or knitted samples on a mannequin, and geometric pattern cutting methods.

Chapter 7, by Helen Hill, completes the journey from design brief to finished garment, by outlining key aspects of knitwear construction. It starts by describing the different methods of manufacturing knitted garments, the machinery that is used and the global locations in which this manufacturing activity takes place. It then explains the stages of construction in detail, including instructions for the specialist process of linking. Focusing on the industrial context, the processes involved in preparing a design for production, including sampling and costing, are discussed. Finally, quality control, labelling, and care and repair are explored.

Chapter 8, by Ian McInnes, examines careers within the fashion knitwear industry. It discusses opportunities to design for established high street retailers and luxury brands, whether in-house or via suppliers. More independent roles are then considered, such as swatch design, freelance work, creating a fashion label and designing hand-knitting patterns. Finally, the alternative routes of trend forecasting, teaching and academic research are profiled. Case studies in every career-focused section provide valuable snapshots of the roles and responsibilities of specialists who have established themselves in various areas of the industry.

Fig. 0.5 The effective designer has a well-developed understanding of both the technical dimensions and the creative potential of knitting. Within this fabric collection, designer Charlotte Cameron has used a range of structures, including mock rib, bird’s-eye jacquard cardigan, plating and all-needle rib.

Fig. 0.6 This highly engineered jacquard fabric was created by Studio Eva x Carola, working in collaboration with circular-knitting-machine manufacturer Santoni to create innovative seamless textiles.

Looking forward

While the book offers vital insights into the practices of today’s fashion knitwear industry, it is important to note that this is a world in flux. The fashion and textiles industry, of which knitwear is a part, is slowly facing up to its responsibilities in terms of global challenges such as climate change. The environmental and social problems associated with the production of clothes are significant and well documented, with negative impacts occurring in all phases of a garment’s life cycle, from fibre production through to disposal. These problems have been exacerbated by the advent of fast fashion, which has brought about massive increases in the volume of garments produced, sold and prematurely discarded. Fashion is now widely acknowledged to be one of the most harmful industries in the world.

In response to these issues, brands and retailers are increasingly seeking to produce their knitwear in a more sustainable way, with consideration for energy use, pollution control and workers’ rights. Indeed, the responsible sourcing of materials and selection of production methods should be an important aspect of every designer’s work, and design strategies that aim to reduce waste and to slow consumption have great value. Some of these approaches are discussed in the chapters of this book. Yet these changes cannot, on their own, do any more than make a bad situation a little less bad; much more fundamental change is needed if we are to address the impact that our industry has on the planet and its people. In truth, we must question everything about the way that we produce, distribute, acquire, use, care for and dispose of our clothes.

Fig. 0.7 Amy Twigger Holroyd’s Reknit Revolution project aims to support home knitters to rework the knitted items in their wardrobes. In pursuing this project, Amy has shifted her design practice from creating collections of knitwear to developing resources that encourage others to act. PHOTOGRAPHER: JAMIE GREY AT RUGBY ART GALLERY & MUSEUM

To some, change may seem unthinkable; the established system appears entirely entrenched. However, as the historical perspective offered in Chapter 1 helps us to appreciate, the knitwear industry is not static; for centuries it has evolved, being shaped by economic, social and political forces and the potential of new technologies. These shifts will continue. In fact, as trend forecaster Helen Palmer explains in her case study in Chapter 8, ‘the fashion and textiles industry is due for a disruptive and radical transformation’.

As future professionals within the industry, the students and young designers whom we have imagined as the readers of this book will be at the forefront of this transformation. This prospect may seem scary. Perhaps it is frustrating to get to grips with the workings of a complex industry, only to be told that it is about to change. But the skills that you develop as a knitwear designer should stand you in good stead to navigate, and even lead, this process of change. The deep understanding of materials, technologies and construction that is developed through the knitwear specialism will always be needed, even if not in quite the same way as today. The questioning approach that is inherent in the practice of design is of great value in imagining how things might be done differently. And the cultural awareness that enables designers to anticipate and even steer tastes and trends will support your ability to see opportunities for change. In short, these uncertain times require creative imagination and technical understanding – core skills of the fashion knitwear designer.

CHAPTER 1

HISTORY AND CONTEXT

by Cathy Challender

Introduction

In order to fully appreciate the context in which fashion knitwear is designed, manufactured, sold and worn today, it is important to gain an understanding of the history of the industry. The role of the fashion knitwear designer, the range of technologies used to produce knitted garments, the traditional styles that are referenced time after time: all can be traced back through centuries of expertise and innovation.

This page from a ledger dated 1859 presents silk warp-knitted samples and manufacturing notes. It is thought to have belonged to Ball and Co., a warp-knitting manufacturer operating in Ilkeston and Nottingham.

This chapter provides an overview of the development of knitting and knitwear, from a medieval craft to contemporary practices, via the seismic shifts of the Industrial Revolution. It explores technological developments, from the stocking frame to today’s machines capable of seamless knitting, and outlines the different strands of the industry that have been created along the way. We will consider the changes in fashion that drove these technological changes, the iconic styles that have emerged and the influential designers who have pushed the boundaries of fashion knitwear over the years. The chapter concludes with an examination of hobby knitting, tracking hand knitting from a respectable Victorian pastime through to a newly reinvigorated twenty-first-century leisure pursuit.

The early industry

Although hand knitting is now primarily known as a hobby activity, it was once a common source of income across Britain and beyond. The practice gradually disappeared with the introduction of the knitting frame, which dramatically speeded up production. This first machine, invented in 1589 to produce fashionable stockings, laid the foundations for today’s technology.

Hand knitting

While the origins of hand knitting are not known, it is certain that the craft is relatively recent in comparison to weaving, which is believed to date back to Palaeolithic times. The earliest examples of hand knitting are fragments of a stocking, discovered in Egypt, dating from the tenth century ad, that display evidence of knitting being a well-established technique. Although we can only speculate about the development of knitting up to this point, earlier archaeological finds provide clues about potential influences. Socks, mittens and head coverings made by using nalbinding – a technique that produces a sturdy fabric that resembles knitting but is made in a different way, by using short lengths of yarn and one flat needle – date from the fourth or fifth century ad onwards.

While the Egyptian stocking proves that knitting would have been practised during medieval times, further evidence is frustratingly scarce. Most agree that knitting originated in the Middle East, spreading via trade and colonization to Europe and the Americas. Requiring no heavy equipment, the craft was easily portable. The types of articles made through knitting at this time would have been diverse, but understandably it is the most precious items, such as liturgical gloves, that have survived. A series of paintings known as Knitting Madonna, from the fourteenth century, show garments being knitted as a seamless tube on four needles, indicating the technique being used and suggesting an important and established industry.

The British seem to have taken readily to hand knitting. The established woollen industry supplied raw material, and the craft became an important source of income in the medieval period. British craftspeople gained a reputation for supplying superior-quality woollen caps and then stockings to Europe and the American colonies. The first knitting guilds were founded in Europe during the thirteenth century, growing in importance during the sixteenth century. These powerful organizations controlled the trade, enforcing standards and rules. The master knitters of the guilds were an elite who travelled, became educated in foreign knitting techniques and were closely allied to the fullers and wool merchants. Qualification as a master required the production of a cap, stockings, a vest and finally a highly complex patterned blanket. When the demand for knitted caps waned, several acts of parliament were passed to protect the knitters’ interests; one enforced the wearing of a woollen knitted cap on Sundays and holidays. Known as The Statute of Servants because the rich were exempt from adhering to it, the act was unpopular and had only limited success.

Fig. 1.1 This pair of woollen socks, made in Egypt in the fourth or fifth century, was constructed by using nalbinding, a knotless netting technique that predates true knitting. © VICTORIA AND ALBERT MUSEUM

During the sixteenth century, an emerging men’s fashion for very short breeches placed an emphasis on the leg. Stockings had previously been made of woven cloth; the elastic properties of hand-knitted stockings made them much more suitable for wear. Paintings from the period show the prominence of the stocking in the royal court, particularly for men. Stockings became increasingly splendid for those who could afford them, with the finest examples being imported at great cost from Spain or Italy. Less is known about women’s stockings at this time; propriety forbade even the mention of women’s legs or the stockings that women wore. Similarly, little is known about the highly refined silk and wool undershirts that were produced during the seventeenth century. A rare exception is a gory account of the knitted shirt supposedly worn by King Charles I at his execution in 1649. This ‘ghastly relic’ was described as a shirt of great perfection, no doubt the work of a master knitter.

Fig. 1.2 During medieval and Renaissance times, the knitting of woollen caps, such as those illustrated, was an important industry in Britain. The process of capping involved the knitting and felting (fulling) of caps to make them weatherproof; they were then shorn, to give a smooth appearance to the fabric.

The elite knitters were a minority, located in the European textiles centres or close to the royal courts. In most regions, the craft was practised as a necessary part-time supplement to other forms of income such as farming or fishing. Hand knitting was encouraged to allow the rural poor to be self-sufficient; to facilitate this, a number of knitting schools had been established in England and continental Europe as early as the sixteenth century. Yet, in reality, knitting provided only a meagre existence for the vast majority of knitters. By the eighteenth century, when stockings produced more quickly and cheaply by machine had begun to overtake the market, hand knitting remained in rural or coastal areas only, where knitting could still supplement incomes from crofting or fishing. The production of Guernsey frocks, a type of working garment adopted by sailors and fishermen from the nineteenth century onwards, provided work for hand knitters. Although the regional patterns for a fisherman’s sturdy, hand-knitted gansey could be elaborate, the knitting of ganseys was not a lucrative activity. The decline continued; by the middle of the nineteenth century, with the notable exception of the knitting performed by the knitters of the Shetland Islands, hand knitting as an industry was permanently diminished.

The stocking frame

The stocking frame, or hand frame, regarded by many as one of the most important inventions of the Renaissance, was invented in 1589, when the fashion for knitted stockings was at its height. Its inventor, Reverend William Lee of Calverton in Nottinghamshire, had aimed to create a machine that would enable him to emulate a hand-knitted stocking. He combined the shape of the upright weaving loom with an entirely new way of making the loops that form a knitted fabric. This method used a row of ‘bearded’ needles arranged horizontally, with one end of each needle fixed into a needle bed; rather than each stitch being worked individually, as in hand knitting, all of the needles formed loops simultaneously. This technology dramatically speeded up the process of knitting, far beyond the capacity of even the swiftest hand knitter.

Fig. 1.3 A portrait of Richard Sackville, Earl of Dorset, painted by William Larkin in 1613. Sackville, known for his lavish lifestyle and extravagant wardrobe, is depicted wearing hand-knitted silk stockings that are embellished at the ankles.

Fig. 1.4 This representation of a spring bearded needle from a Lee stocking frame (hand frame) depicts the needle’s three important parts: the shank upon which the old loop was formed; the beard, which retains the new loop and enables the old one to pass off; and the eye, which receives the end of the beard.

Lee’s first stockings were made of wool, knitted at a relatively coarse gauge equivalent to today’s 8 gauge knitting machines. Despite the inventive brilliance of the machine, Queen Elizabeth I denied Lee a patent because she felt that his invention would harm the livelihoods of British hand knitters. She indicated that, if Lee’s machine could knit silk stockings to compete with foreign imports, his request would be viewed more favourably. With help from skilled French artisans, Lee achieved this task: by 1599, his frame could knit silk stockings and waistcoats. Still denied support from the English court, he relocated to Rouen, a centre for textiles in France. He hoped for more favourable treatment from King Henri IV, but these hopes were dashed when the king was assassinated. Lee died in France without seeing the full reward for his efforts.

The use of the stocking frame was, however, growing. While a growing number of frames were soon being used in the East Midlands and as far away as Dublin, for producing woollen stockings, the majority of frames were based in London, close to the royal court. Here, silk stockings and other items were made with an eye to the latest fashions – now with the fabric at a much finer gauge. Despite the success of the trade, it was not until 1657 that the Worshipful Company of Framework Knitters was incorporated by Oliver Cromwell. The company controlled the organization of the industry and the taking on of apprentices; in the early days, it limited development with a succession of rules and regulations. In rural areas further from London, especially in the East Midlands, the company was less able to exert its influence. By the early eighteenth century, the use of the frame had progressed sufficiently for the towns and villages around Nottingham, Leicester and Derby to become a centre for stocking-making of all types.

The first frame-knitted stockings were knitted flat by machine and then seamed by hand; this was an important and distinctive feature. The calf and foot shapings were achieved through the manual removal of stitches from the selvedge needles, producing the same distinctive fashioning marks as achieved by hand knitting. However, the replication of hand-knitted stitches required laborious effort on the part of the framework knitter. The purl (reverse) stitches so easily formed by hand had to be made on the frame by individually laddering then reworking a stitch from the opposite direction. Rib fabrics, which combine columns of knit and purl stitches, are therefore particularly difficult to work on the early Lee frame.

A succession of technical developments during the eighteenth century enhanced the machine’s capabilities. The invention of the tuck presser in 1740, for example, introduced the possibility of patterning on the frame. In 1758, Jedediah Strutt from Derby patented the rib attachment – a second set of needles added to Lee’s stocking frame. The rib fabrics produced were more elastic, giving an improved fit that was in accordance with the fashion of the day. Just a few years later, the Petinet knitting machine enabled ornamental pierced patterns to be automatically added into the ‘clock’ of a stocking, at the ankle. In a further significant development, the stocking frame was mechanized by Samuel Wise in 1769. These improvements, together with the appeal of the fine fabrics that could now be achieved by the machine, meant that, by the end of the eighteenth century, frame-knitted stockings were more popular than stockings that were produced by hand.

The Industrial Revolution

The deep societal and economic changes brought about by the Industrial Revolution in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries transformed every aspect of British life – including, inevitably, the knitting industry. Technological innovations and a shift to factory production, coupled with changes in fashion, led to machines being used to produce a wider range of garments.

Fig. 1.5 The buildings that are now Ruddington Framework Knitters’ Museum in Nottinghamshire were formerly frame-knitting workshops. The distinctive long windows maximized the light available for performing the highly skilled craft of framework knitting. COURTESY: RUDDINGTON FRAMEWORK KNITTERS’ MUSEUM

A changing stocking industry

Before the Industrial Revolution, it took up to five hand spinners to keep the stocking knitter supplied with yarn. In the second half of the eighteenth century, spinning was moving out of the home and into the efficient production-focused environment of the mills. This shift was prompted by a succession of inventions, including those of James Hargreaves’ horse-powered spinning jenny in 1764, Richard Arkwright’s water frame in 1771 and Samuel Crompton’s spinning mule in 1779, which vastly increased yarn production. With yarn being readily available, it was the framework knitters – still working in the home – who were struggling to keep up with the demands of the industry.

Typically, men operated the knitting frames; this was an arduous and skilful task. It could take years to become a master knitter of fancy goods and earn enough to generate and sustain a sufficient income. Even then, framework knitting provided only a precarious livelihood. Women and children undertook preparation of the yarn; women also seamed the stockings. The specialist task of chevening (embroidering) women’s stockings was undertaken by women and girls, who were usually poorly paid outworkers or apprentices, housed under the supervision of a mistress. Some successful framework knitters of this period – along with men from unrelated trades – set themselves up as hosiers, renting frames out to other knitters, to work at their own homes, and organizing the supply and distribution of yarn and finished goods. If the hosier had sufficient workshop floor space, he might employ knitters and keep apprentices to work a number of frames within the workshop. Some hosiers acquired considerable fortunes; this imbalance of power caused considerable friction between the individual knitter and the powerful hosier. The introduction of frame rents, which essentially passed on all of the costs of production to the knitter, exacerbated this situation and led to the outbreak of Luddite riots in Nottinghamshire.

Fig. 1.6 G.H. Hurt & Son Ltd, manufacturers of fine lace shawls, was established in 1912 in Chilwell, Nottingham. Master knitter Mr Henry Hurt, the grandson of the company’s founder, is one of the few people able to work an eighteenth-century hand frame today. COURTESY: G.H. HURT & SON LTD

Various influences, including wars with the French that resulted in short supplies and trade embargoes, led to a downturn in the industry in the early nineteenth century. A change in fashion had a significant impact: the introduction of trousers for men rendered full-length stockings unnecessary. The fashionable and upper classes abandoned breeches and stockings for full-length trousers and half hose (socks); a trend for knee-high boots meant that not a glimpse of hosiery could be seen. Stockings could no longer command the high prices of preceding eras, and the inexorable decline of the stocking as a men’s fashion item had begun.

Another shift in fashion, however, was to drive a new wave of technical innovation. Responding to the fashionableness of expensive handmade lace, inventors concentrated on developing the stocking frame to produce a viable substitute. The earliest piece of machine-made lace is credited to hosier Robert Frost. Along with other early developments, this innovation provided work to framework knitters and thousands of female embroiders who decorated the resultant fabric. John Heathcoat developed the technology further and in 1809 patented his bobbin-net machine, giving rise to the wealthy Nottingham lace industry of the nineteenth century. Men working the lace-making machines earned several times as much as a framework knitter.

Fig. 1.7 This nineteenth-century framework-knitted sampler shows lace patterns for stockings, produced by Allen Solly & Co. Ltd of Nottingham. This influential family firm supplied many of the royal families of Europe.

Knitting innovations

While the British hosiery industry entered a period of stagnation during the nineteenth century, French, American and German inventors strove to increase the speed at which knitted fabrics could be produced. Their major innovations commenced with the invention of the circular frame in France in 1798. The needles of this machine were arranged in a rotating ring; this arrangement was well suited for conversion of the machine to be run by steam power. Although the British were slow to adopt this revolutionary machine, in America, it was further developed in the mid-nineteenth century in order to meet the growing demand for mass-produced knitted goods. At this time, the circular knitting machine could produce an amazing 350 courses of knitted fabric a minute.

In 1847, the self-acting or latch needle was invented by Matthew Townsend of Leicester, improving upon the bearded needle used in the original frame. The impact of this small yet revolutionary invention can hardly be imagined. Townsend’s needle was widely adopted by the circular-knitting-machine industry in the USA for its speed, versatility and simplicity of operation. And it was not just the large-scale circular knitting machines that utilized the new technology: small, circular, latch-needle machines such as the Griswold and the Harrison ‘Little Rapid’ were produced for domestic use. These machines were advertised in women’s magazines, targeting those wanting to earn extra money by knitting socks and other items at home.

Fig. 1.8 The latch needle, invented in 1847, revolutionized knitting technology and is still in use in the latest machines. The latch enables a stitch to be formed as the needle slides forward and backward, picking up the yarn and drawing it through the loop of the stitch from the previous course.

The invention of a series of patterning mechanisms enabled the knitting of patterns, textures and colour changes. Though initially and famously applied to the weaving loom by J.M. Jacquard in 1805, the punchcard patterning mechanism was applied to a wide range of knitting machines throughout the nineteenth century. Increasingly decorative novelty fabrics, affordable for the middle and lower end of the market, were produced. Another significant development was warp knitting. The first warp technology, invented in England during the eighteenth century, was an attachment for the hand frame and was used mainly to decorate stockings. In the nineteenth century, German manufacturers developed the potential of the warp attachment as a machine in its own right. Warp-knitted fabrics are ideal for items where more stability is required in the fabric and for cut goods such as gloves.

Fig. 1.9 Dating from the late nineteenth century, the Griswold hand-cranked, circular sock-knitting machine was used both for production in workshops and by the home knitter. Circular sock-knitting machines were put into active service in both world wars, for the knitting of army socks.

Transforming the frame

While knitters were still working the hand frame in their homes in the mid-nineteenth century, steam power and factory production were soon to transform the industry. Associated with a series of patents made starting in 1860, the Cotton’s steam-powered frame brought together good ideas previously pioneered by other inventors. While this innovative ‘straight-bar’ machine still employed bearded needles and had many parts that were similar to those of the hand frame, it used a flatbed to produce fully fashioned garments, automatically shaped at the selvedges, for the first time. At the time, the Cotton’s frame was considered to be the most important development since William Lee’s invention of the very first frame. In comparison to its forerunners, this machine was a giant. Its size, coupled with the move to steam power, necessitated the move from domestic production into large purpose-built factories, transforming the skylines of Nottingham and Leicester.

Fig. 1.10 Established in 1784, John Smedley Ltd is the world’s oldest knitwear manufacturer. The entire production operation is carried out on their site at Lea Mills in Derbyshire. COURTESY: JOHN SMEDLEY LTD

The Cotton’s frame had a major impact on manufacturing: first eight, then twelve and later up to thirty-six automatically narrowed stocking lengths could be produced at once. Furthermore, the number of men needed to operate the new machines steadily reduced. With the machine’s gentle knitting action, fine wool yarns could be used for the first time. These factors made the Cotton’s machine suitable for the increasingly important production of knitted underwear garments. While hand-frame knitters in the Scottish Borders had concentrated on making high-quality underwear for the home and export market since the 1830s, production using the Cotton’s frame meant that quality knitted underwear was affordable for the middle classes for the first time. Demand steadily grew for these items, driven in no small part by German guru Dr Gustav Jaeger, who advocated the use of full-body, woollen, knitted undergarments, known as combinations, to promote health. His ‘sanitary underwear’ was produced by John Smedley Ltd in Derbyshire until the Jaeger factory and brand were established. Jaeger was ahead of his time and soon inspired other manufacturers who recognized that the elastic, health-promoting properties of knitwear could be exploited across a range of intimate items.

While some making-up, trimming and finishing of hosiery and underwear would continue in the home, much of this activity would soon join the working of the knitting frames in the factory setting. This shift was driven, once again, by the invention of new technology and the introduction of steam power. Linking machines (also called linkers), used to join knitted fabrics together with a chain stitch, were invented by a Nottingham company, B. Hague, and first installed in a factory in 1866. Julius Kohler invented the cup seamer in 1874 to quickly join the selvedges of shaped goods. Standard lock-stitch sewing machines were also used for attaching non-elastic trims. These processes required skill; it took months of practice before women, paid by the piece, could earn sufficient remuneration for their work.

Fig. 1.11