20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

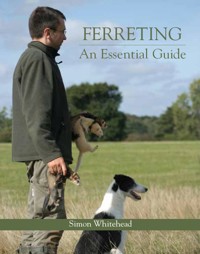

During the last twenty years there has been a dramatic increase in the rabbit population and this development has, in turn, been accompanied by a renaissance in ferreting. The appearance of an up to date, informative and instructional guide to this traditional form of rabbit control is therefore timely, and will be welcomed by those with an interest in country pursuits.Ferreting - An Essential Guide contains all the vital information you require in order to work ferrets successfully to catch rabbits using tried and tested traditional methods. It is based on the author's considerable practical experience, gained over many years, of ferreting both professionally and for sport.Outlines how to acquire, care for, and manage ferrets; examines how to effectively work a team of ferrets; discusses in detail netting, digging and the role of the ferreter's dog; analyses the behaviour and characteristics of rabbits, their feeding habits, and how their warrens are constructed and laid out; considers the essential equipment that is required in order to catch rabbits efficiently; analyses the latest electronic ferret finder sets and how they can be used. Written by an experienced professional ferreter and countryman. Ferreting is experiencing a renaissance, with more ferreters practising their art throughout the country. This up to date, informative and instructional guide will be welcomed by those who already work with ferrets, or who are on the point of taking up ferreting. Brimming with practical advice and tips, it is based on the author's considerable practical experience. Beautifully illustrated with over 124 colour photographs and 9 diagrams. Simon Whitehead is a professional ferreter, author and regular contributor to country sport magazines.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 326

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

FERRETING

FERRETING

An Essential Guide

Simon Whitehead

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2008 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2013

© Simon Whitehead 2008

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 664 2

Disclaimer

The author and the publisher do not accept any responsibility or liability of any kind in any manner whatsoever for any error or omission, or any loss, damage, injury or adverse outcome incurred as a result of the use of any of the information contained in this book, or reliance upon it.

Frontispiece picture courtesy Steven Taylor.

Contents

Dedication and Acknowledgements

1 Acquiring and Caring for a Ferret

2 The Ferreter’s Quarry: The Rabbit

3 The Ferreter and the Land that is Being Ferreted

4 The Ferreter’s Equipment

5 Ferret Retrieval Devices, Methods and Options

6 Working Your Ferrets

7 Why We Do It

Appendix: Ferreting and the Law

Glossary

Index

Dedication

This book is dedicated to all those who wish to promote the craft of the ferreter and to educate others in the skills involved in this traditional country pursuit.

Acknowledgements

The writing of this book has at times been a roller coaster of emotions, but I hope that the end result will be of interest to all those who ferret or enjoy country pursuits. I could not have compiled the book without the help, encouragement and assistance of so many friends. In particular, I would like to thank Steve Taylor for his countless hours, if not days, accompanying me around the countryside, experiencing his own journey with the camera; I hope his journey with the ferrets is as fruitful. His advice and excellent photographs are a testament to his passion for the countryside and the portrayal of its traditions. Also, thanks to Greg Knight, Craig McCann, Nigel Housden, Ivan Ambrose, Eaglemoss Publications Ltd and Bob Lee for their permission to use their photographs and illustration; Deben Group Industries for their help and support of the ferreting community; Bob, Kev, Torchie, Bill, John, Martin and Pat from Bridport Nets for their help, guidance and constructive comments relating to the netting section; and Ivan, Norman, Paul and Steve for their excellent help and much needed assistance over the years, long may it continue. And last, but definitely not least, my grateful thanks go to Jules, and our daughter, Grace. Jules has patiently tolerated my unusual lifestyle and provided me with unwavering support and encouragement.

The author and publishers are grateful to the following for the supply of photographs: Ivan Ambrose, Eaglemoss Publications Ltd/ The Hayward Art Group, Nigel Housden/Pinsharp Photography, Greg Knight (www.ruralshots.com), Bob Lee, Craig McCann and Steven Taylor.

CHAPTER ONEAcquiring and Caring for a Ferret

In the popular mind, ferreting has always been associated with the working class, being viewed as a rural pursuit that provided a chance for the workers to escape the harsh reality of their daily lives and sample the tranquillity and clean air of the countryside. In fact, workers engaged in ferreting out of necessity, in order to provide food for the table, although after long hours spent down the mines or in factories, the feeling of freedom they must have experienced once out ferreting is one that we cannot truly appreciate nowadays. However, contemporary ferreting still provides a way for people who are urban-based, due to work or family commitments, to sample what this green and glorious land has to offer whilst exercising the instinct we were born with, which is to hunt, whatever the quarry. In the following pages, we will consider in depth the art of working ferrets to catch rabbits.

Once the leaves start to fall, nature is warning us that the colder months are on the horizon and, with them, the ferreting season. To go ferreting, you will need some equipment and permission to hunt on private land, but, above all else, you will need a team of ferrets. Preparation for the new season should start just as the last one finishes, although unfortunately a large proportion of ferreters unwisely switch off from rabbit control come the end of the season. Some sell their ferrets, being unwilling to look after them during the vacant summer months, then restock the following autumn. These so-called ferreters are not worthy of the name; they are just people who go ferreting. Once the season has finished, just like a football team manager in the close season, a true ferreter’s thoughts will turn towards the team of ferrets required for the forthcoming season. Decisions have to be made. Am I happy with my team as it is? Should I breed from my existing stock or bring in new blood? Where should I strengthen the team or do I need to replace any old stock?

For my own ferreting, I require many ferrets, from the fast, flowing ferret to the slow, methodical worker that is stubborn enough to stay and grind the rabbit down. All these types have a place, as the warrens worked over the year will be as individual as the ferrets themselves. In direct comparison with modern-day football, ferreting is now a squad game.

Ferrets are the most underestimated of our working animals. Over the years, the price of dogs has gone through the roof, while the price of a ferret has unfortunately remained low, with the result that people may purchase them without due consideration for their subsequent welfare. Also, we shouldn’t forget that the ferret is a household pet across the nation. Since becoming a popular pet, their instinct to hunt has inadvertently been weakened. However, husbandry and sensible management of our ferrets should ensure that they reach the high standards we require. Only then will we be doing these little grafters the justice they truly deserve.

If you are a first-time ferreter, then you should set about learning as much as possible about ferret husbandry and management. Much advice will be given within these pages, but there are also many good books on the market that deal specifically with this subject. If you are an old hand, it doesn’t hurt to run through the basics once again. Getting the ferrets’ welfare right will go a long way towards ensuring that they will work efficiently in the field. It should always be borne in mind that, as with all of our domesticated animals, we are responsible for our ferrets’ welfare 365 days a year, through holidays in all weather conditions.

The apprenticeship of ferreting is a long and sometimes arduous journey. (Steven Taylor)

The manner in which our ferrets are kept is often dictated by our personal circumstances. The space available, the amount of ferrets kept and how often they are worked will suggest the best way to house them, although the basics remain the same despite differing circumstances. Ferrets require good housing and food, as well as plenty of handling, and it goes without saying that the more ferrets you have, the more time it will take to look after them. The average lifespan of the ferret is six years, although many now live longer than this. A working ferret’s age might be lower, especially if it is worked a fair amount, but with higher welfare standards this age is slowly rising.

Try to ensure that you start off with good stock from a trustworthy breeder. The sale of ferrets at markets and shows is sadly rising and while the demand for the ferret is there, people will continue to breed ferret after ferret whatever stock is available, purely for financial gain. If a ferret costs only a few pounds, is its value being truly appreciated? The question we should be asking ourselves if we decide to buy a ferret from one of these venues is: Will they be up to the task we require of them?

THE FERRET

But first, let us explore the make-up of the ferret itself. The ferret is a combination of a well-proportioned, elongated body, lean, muscular legs, feet with pads under them and sharp claws. The claws are vital to the ferret, as they need these for hunting, climbing and clawing at their food. Their everyday lives include a lot of climbing and exploration of their housing in order to keep them mentally and physically stimulated whilst not out hunting. The ferret’s head is streamlined, with a nose and whiskers that are designed to detect their quarry in the darkness of the underground hunting domain. Their eyesight isn’t the best because they are working a lot underground. The body and functions of the ferret have been designed and evolved to suit their surroundings.

Another rabbit, another learning experience. (Greg Knight)

The ferret has an insatiable lust for hunting. (Greg Knight)

Ferret Colours

The colour of the ferret ranges from the popular albino, a white or creamy animal with red eyes, to the black polecat ferret, which bears the closest resemblance to the wild polecat. There are over twenty different colours and combinations, but as far as working is concerned it is just a matter of dark or light, white or coloured – colour doesn’t distinguish between a good or bad working ferret.

The colour of a ferret doesn’t affect its ability to work underground as it is in darkness. The rabbit cares little for colour in its bid to survive its encounter with a ferret, but colour does affect the way in which we perceive how the ferret works above ground. As our climate is changing, so are the animals and plants that live on and underneath its surface. The undergrowth is no longer dying back or hedgerows lying bare and the trees losing their leaves in the early seasonal months of September and October, with the result that there is a lot of greenery around at any given time of year. As our surroundings change, so must we. I now work a lot of white or lightly coloured ferrets as opposed to the darker ones, due to the ease of detection once back on top of the ground.

Many falsely believe that a true ferret is white and the darker polecat ferret is in fact a wild animal. The polecat is a wild animal; its name is simply used to describe the colouration of the wild ancestor on the domestic version. When I first started ferreting, only a handful of colours was available but that was many moons ago and things have certainly changed since then. However, to say that one colour of ferret works better than another due to colour leading to specific personality traits is simply inaccurate.

THE JILL VERSUS THE HOB

The female ferret (known as the jill, bitch or doe) and the male ferret (known as the buck, hob, dog or jack) differ in many ways. The difference is not only physical in terms of size, shape and appearance, but also in their attitude to work as they can be affected by hormones when coming into and during their breeding seasons. In the present climate, we have ferrets of all shapes and sizes, from minute ferrets of both sexes to ridiculously large ferrets. Both extremes, I find, are unsuitable for ferreting. Among normal-sized ferrets, the jill is the smaller of the sexes, usually by about a third, but she is powerfully proportioned with a streamlined body and good mental strength that gives her an excellent attitude towards work. The jill works with gusto, reliability and dependability, but with her speed comes a lack of stamina. Her high standard of efficiency only lasts for a few hours of constant work. Of course, ferrets can work all day if pushed, but they will not work as efficiently when tired. A good ferret glides effortlessly around the warren, disturbing very little other than the rabbits’ sleep.

The base colours of the ferret, the albino and the polecat ferret. (Steven Taylor)

Jill ferrets come in all shapes and sizes. (Steven Taylor)

The hob, on the other hand, is a larger and more powerful animal, although the larger head and stronger physique of today’s average male ferret are simply too large for successful ferreting, as their size means that they cannot pass through the nets. In addition, fitting the standard ferret-finder collar is difficult and carrying them about is a logistical nightmare. The ferret is now kept better than at any time in its history, leading to larger and stronger hob ferrets. The hob has a large bearing on the genetic make-up of the litter. Nowadays, ferreters are trying to reduce the size of the hob ferret, not to the minuscule versions that resemble the stoat, but to the ideal size of the average well-proportioned jill ferret, while still retaining the typical mindset of the hob. The hob tends to have the attitude that if the rabbit won’t bolt (fee or escape), it will try to persuade it to do so, or alternatively it will stay with the rabbit until the ferreter digs them both out. This is not how everyone likes to go about things, so if you don’t like this attitude, don’t work this type of ferret. Once you have worked the same ferret or ferrets for a year or two, you have come to know their characters, strengths and weakness first hand and so can work them accordingly.

A range of different-sized hob ferrets. (Steven Taylor)

The polecat ferret, a reference to its colouration and not its genetic make-up. (Steven Taylor)

There are undoubtedly regional differences in the size of ferrets, the result of generations of ferrets being bred for and adapting to the type of work in their area. The rock-filled Peak District and the Lakes require a smaller ferret, lean enough to ft into the gaps and voids of rocky warrens and stone walls, whereas sandy areas or clay warrens require a larger ferret. While you can work any ferret in any area, a ferret that is too small for the larger tunnels may be overwhelmed, whereas a large ferret will struggle in the tight, confined tunnels of rock, chalk or similar hard substrates.

The main problem with ferrets that are too small is that a rabbit can easily kick them off; they haven’t the physical capability to stop a rabbit whilst running around in the pipes. I feel the modern fascination with the so-called greyhound or pencil ferret has changed many ferreters’ perceptions about how a modern ferret should be. Some ferreters advocate the inclusion of wild polecat blood into their ferrets’ bloodlines, but after experiencing this mix a few times, I don’t believe that you will ever beat a well-bred working ferret from pure working domesticated stock.

In the past, these regional differences went largely unnoticed, but with better modes of transport people and their ferrets started to move areas and so these differences gradually became apparent. This has had an impact upon attitudes to breeding specific types of ferret. Whereas once the vast majority of ferrets were bred from any available hob, specific breeding programmes gradually developed that led to the widespread use of suitable hob ferrets for siring litters.

The jill ferret is generally worked more frequently than the hob. Due to her size, she is able to pass through the nets without much disturbance and has a quicker work rate compared to the physically larger hob. Many ferreters like to work small jills, believing them to possess a mystical ability to get behind a rabbit that is stuck in its stop end and so force it to bolt. However, those who have dug a rabbit out of its stop end will know how hard it is to prise out. The shape of the stop end was built by and for the rabbit. If alone, the rabbit’s body fits snugly into its excavation with its body gripping the surrounding surface of the tunnel, holding it tight and protecting it from attack. It is impossible for even a small ferret to squeeze past the millimetre’s worth of gap between the rabbit and tunnel.

The hob may be a physically slower worker than the quicker jill, but this isn’t necessarily a bad thing and as a result the number of ferreters working more hobs than jills is on the increase. With a slower work rate comes the conservation of energy and when this is combined with the hob’s focused attitude towards work, you get a slow, methodical worker of consistent efficiency. Jills tend to work in a more manic style, fizzing about the warrens, in the process expending more energy, which impacts upon their endurance and efficiency. However, to an extent the size and sex of the ferret are immaterial – it is the size of the fight inside them that is vitally important.

Both male and female ferrets are affected by hormonal changes coming into the spring period; the hob usually comes into season first. If you do not intend to breed from a hob, it may be a good idea to have him castrated (neutered). Come February and March, the minds of the un-neutered ferrets tend to wander, but the neutered ferret will concentrate on the job in hand. Teams of ferrets, both familiar or strange to each other, will waste valuable time underground either squaring up, ready for a skirmish, or will flirt with each other instead of concentrating on getting the work done. It is unwise to work ferrets of both sexes together whilst in season as it is obvious what the result will be. In certain areas of the UK, working jills in season attract the attention of the wild polecat; I know of several litters over the years that were the results of a union whilst ferreting. A good ferret that knows its job inside out is worth its weight in gold but even these succumb to seasonal ‘distractions’.

The darker ferret is often overlooked against the greenery of our countryside. (Greg Knight)

Before you purchase your ferrets, you must decide what combination you intend to keep and how many of each. You can maintain your ferrets in courts of jills only, hobs only, or a combination of both. I usually keep all of my ferrets (jills and hobs) together in one court. Throughout the winter they live in harmony, but I have to act swiftly prior to the spring and summer breeding season, separating the entire (non-neutered) hobs and leaving only the castrated and vasectomized hobs in with the jills. Without swift action, you will end up with a litter of young ferrets (kits); it is surprising and rather saddening to hear just how many young ferrets are born this way, through ignorance of basic husbandry.

PURCHASING A FERRET

One of the most important but often most frustrating aspects of ferreting is the purchasing of ferrets. It is unfortunate that not all ferrets will work and that is why I have included a few words of warning to try to avoid the pitfalls that have caught out many a ferreter. You should never buy a ferret on a whim or at a show, as you will not have the slightest idea about its background. Think carefully before you buy any ferret – check out the homes, the parents and the state of their welfare, as opposed to the convenience of just buying any ferret from any background when it is available. Resist the temptation of falling for the tale of the ready-made, tried and tested ferret. If a ferret was that good, why would anyone want to part with it? It is preferable to start with a youngster bought from a reputable source, as you will know it hasn’t got any secret bad habits lurking in its history.

Picking the right ferret is just the start. Like all animals, its upbringing will play a large part in its future habits, both good and bad. The best age to purchase a ferret is undoubtedly when it is between seven and nine weeks of age. A kit (a young ferret under sixteen weeks of age) is at an age when you can raise it in the desired manner without any fear of it having already acquired too many bad habits. The reason why so many people purchase a youngster over an adult is of course its teeth. The teeth and jaws of a youngster are undeveloped so therefore do not have the power or sharpness of an adult and this will be noticeable when you start to train it in the ways of being handled.

THE YOUNG FERRET

Ferrets are usually born in the late spring/early summer, are weaned at around six weeks of age and then are generally rehomed at between seven and nine weeks of age. When properly reared, these youngsters will start to work slowly about November time, although, like every animal, some will be naturals while others will require a bit longer to get used to the reality of being a working ferret. Remember, how you treat these animals up to the end of their first working season will shape the rest of their working lives. Bad habits are easily made and take time to correct, if at all. A lot of ferreters fall into the trap of giving precedence to the ferret that seems to be working best, thus not giving experience to another youngster that really needs it. Not all ferrets will work to your standards, so a degree of weeding out will occur, although I have moved on a ferret or two myself only to see a year or two later that they have evolved into first-class workers for their new owners. Unfortunately, this happens from time to time to everyone who works with animals.

Future hopes and expectations are always high for young ferrets, though not all of them will make the grade. (Steven Taylor)

HANDLING

There is nothing more comical than a hutch full of ferret kits, all as mad as a box of frogs. Their naivety, youthful exuberance and energy ensure that they will spend large amounts of time mimicking their hunting skills on each other. It looks far worse than it is and is a vital part of their upbringing. But play-fighting and using their teeth on each other is one thing; using them on your hands is a definite no-no.

To pick up a ferret is simplicity itself. (Steven Taylor)

The ferret is an animal that needs to be handled, stroked and played with as much possible. Getting them used to your hands is the most important part of their welfare, for without the ability to pick up the ferret, how are you going to clean out their housing, never mind go ferreting? There are several methods of getting the ferret out of its nippy stage. The method I use has served me and my friends well over the years and although I am open to seeing new methods, I am amazed at some of the methods people have tried to convince me will work. One misconception is that all ferrets are born biters. This is utter nonsense. If the parents have been well-handled, fed and looked after, the genes inside the youngsters will carry the same traits. Young ferrets do not know right from wrong or the difference between a hand and a playmate or chunk of food, so in the following weeks and months you will be educating the kits about what is acceptable.

To get the ferret used to being handled, you must accept that both your and the ferret’s patience will be tested, as you are dealing with a little immature animal, just like a pup. Ferrets, like all animals, will detect the slightest nerves or hesitancy, so you must always pick them up in one swoop. Never play about in front of the ferret, pulling your hand to and fro, as this will just encourage the kit to jump and hang on with its teeth to the first thing it meets, which will be your hand. Talk calmly to the ferret as you pick it up.

To pick the ferret up is simplicity itself. Picking it up from the stomach area, between the front and rear legs, a kit will be resting in the palm of your hands, but if you are uncertain of its likely reaction or if it is a adult ferret, you can hold it around the neck, secure in the knowledge that it cannot turn around and bite you in such a hold. To hold a ferret safely in such a hold, you pick the ferret up by putting your thumb and forefinger gently around the ferret’s neck and the three remaining fingers behind the front legs and around the stomach area of the ferret. You should get the ferret used to being picked up in as many different ways as possible – place it on the ground, play with it and pick it up lots of times, as you need your ferret to be used to any eventuality whilst out ferreting..

The method I use to stop ferrets nipping is as follows. Play with the ferret as if you were a fellow ferret. Rough it up a little, tickle its stomachs or its ears and it will react by trying to bite you, quite normal for any youngster. When it goes to strike, either gently pinch its nose or gently flick it with your finger in order to shock the ferret. You are sending out the message that you are not there to be bitten. Other methods practised to eradicate biting include forcing a knuckle inside the ferret’s mouth, or simply handling the ferret and ignoring the nips, but, with this latter method, one day the adult will bite and it will hurt. Better to have a ferret that is bullet-proof than to be always thinking it may bite, which will undermine your confidence and the ferret will pick up on this.

Once a ferret is at the stage where it does not go for the strike, I put a little spittle or milk on my finger and let the ferret lick it off. When the liquid has gone, it is natural for the youngster to have a nibble. Again, repeat the gentle tap or flick to the nose. In my opinion, this isn’t cruel, but is what we must do in order to get the ferret to associate biting human beings with discomfort and to enable us to have a working relationship with it. I have been criticized by those who regard this method as being somewhat barbaric. Their preferred method is to play with the ferret and just let it bite. When it does, and believe me it will, they hold the ferret up to head height, look it in the eye and say in a stern voice ‘no’. This apparently stops the ferret from biting again. This method has never worked for me, but you can make up your own mind as to its effectiveness.

Do not forget, though, that the rate at which the ferret grows from a little eight-week-old kit to a full physical specimen at eighteen weeks is quick. The mental growth comes later, but trying to get a sixteen-week-old ferret to stop nipping is a lot harder and more painful, due to a set of fully grown teeth, than with a smaller, weaker youngster, so don’t leave this job too late.

All ferrets must be accustomed to having their handlers standing over them and being picked up without reacting. (Steven Taylor)

TRAINING

Ferrets require very little in the way of training, as their method of working is instinctive. Reinforcing this instinct by feeding the kits rabbit with its fur left on gets them accustomed to the smell, taste and texture of the rabbit. Correct handling from a young age will ensure that when they are getting overexcited on their first few trips, you should be able to pick your ferrets up without any accidents.

With daily handling, the ferret will grow up realizing that the hand isn’t on the menu. Accidents will happen, especially with excited youngsters, but this is no excuse – a bite is still a bite.

It is a good idea to get a ferret used to the ferret-finder collar before its first ferreting trip. By placing a collar on the ferret for short spells of time at home many weeks before it goes ferreting, it will adjust to the strange sensation of wearing the collar. This helps to reduce the time the ferret spends trying to rub off the collar, especially when it should be concentrating on finding rabbits.

One aspect of training often overlooked is getting the ferrets used to being stood over before they are picked up. Whilst ferreting, the novice ferret will experience a mixture of excitement and nervousness and when approached to be picked up it can often dart back down a hole if it is not used to being handled in this way.

This is a far more common problem than many would like to admit to. The ferret is a very small animal that has just been placed in an environment that is a world away from its hutch or run. The experiences it has just encountered will excite as much as frighten it, and this is when your training pays off. It is vital that the ferret gets accustomed to being picked up in as many different ways as possible, taught to go in, through and out of the pipes that make up a warren, but, most importantly, it must be used to being picked up from the ground. Put yourself in the position of the ferret and imagine what it looks like to be stood over by a giant whose hand is reaching down towards you. By acclimatizing a ferret to this action, it will not be intimidated by the approaching hand and will react well when coming out of the warren. Too many ferreters are impatient and grab a ferret when it refuses to clear the hole. This is a sure-fire way to getting a ferret to ‘skulk’. Skulking is when the ferret will appear at the mouth of a hole and refuse to come within arms’ reach, instead going back down the hole, simply to reappear once you have retreated. These youngsters need coaxing out, gently and calmly, and with practice and experience they will improve. If you aim to see things from the ferrets’ perspective as well as your own, you will begin to understand how to avoid instilling bad habits in the young ferret.

The carrying box is another object that requires familiarization, but this is done by simply placing the ferrets in the box whilst cleaning out their hutch at home. All being well, once the calendar has reached its eleventh month, the young ferrets should be ready for work.

COMING INTO SEASON

As the winter turns towards spring, the ferrets will come into season. The physical signs of a ferret in season are obvious. The hob is usually first; his testicles will drop while his aroma will increase. The jill’s vulva will swell and she will stay in season until mated or given an injection by a veterinary surgeon, or she will naturally come out of season around September. The breeding season of the ferret is governed by the hours of daylight over the hours of darkness (photoperiodism). Both sexes will exhibit different characteristics due to the hormone imbalance.

One of the many old wives’ tales connected with ferreting states that if you don’t breed from a jill she will die. The act of mating (coitus) stops the build-up of oestrogen; it is this act and not the birth of the litter that removes the ferret from her season. If you do not want a litter, you can remove the jill from her season by using a vasectomized hob ferret (hoblet). If a hoblet is not available a jill-jab is available from the veterinary surgeon that will have the same effect of removing the jill from her season. The jill usually comes into season twice a year and sometimes the removal – by whatever method – can result in a phantom pregnancy, resulting in all the characteristics of a real pregnancy (nest-making, producing milk, broodiness and character/mood swings), but without the litter of kits.

Neutering

Neutering is the only completely effective way of preventing any unwanted litters and fights between inmates, and of reducing the aroma of the summertime hob. At a time when a lot more ferreters are utilizing the working hob, neutered hobs (hobbles) can be kept with each other and with jills for the full year without the usual scraps, scrapes and pregnancies that will otherwise result. Sometimes confusion arises when taking a ferret to the vet to have an operation such as a vasectomy, or to be castrated. An entire hob is one that is left naturally alone; he will come into season and has the capability to breed with an in-season jill ferret, and get aggressive with other in-season hobs. A hoblet is a hob ferret that has been vasectomized. He acts exactly the same as an entire male ferret (hob) and can take the in-season jill out of season by mating with her, but because he has had a vasectomy, he is unable to get her pregnant. A hobble is a castrated male ferret. Having had his testicles removed he is incapable of breeding. Hobbles generally live in harmony the whole year round with both hobs and jills.

With the increased awareness of the importance of the jill’s season, the use of a vasectomized hob is becoming the popular way of removing the jill from her season. After a simple operation and a quarantine time of around six weeks, this hoblet can remove a lot of jills from their seasons during the summer months, proving a lot more cost-effective than the jill-jab. There has been a lot of controversy concerning the jills’ season and the thorny subject of removing them from it, but I feel you cannot take any risks with your ferrets’ health. How would you feel if your jills succumbed to the grim reaper a few weeks before you were due to start ferreting just because you had done nothing about their season?

It is important for young ferrets to be accustomed to the smell, taste and texture of rabbit before their first encounter whilst at work. (Steven Taylor)

THE FERRET’S DIET

When you decide to go ferreting, it is necessary to plan your ferrets’ feeding regime to gain maximum efficiency and results. This will depend upon the workload ahead, the warrens and their positions, the amount of hours spent working and the time of year you are ferreting. You will need to feed your ferrets to suit the day ahead.

In the past, the ferret’s diet has been, well, not the best, but it hasn’t always been bread and milk slops as popularly assumed. In several old readings I have found evidence of the ferret being fed meat or meat scraps, their natural diet. Nowadays, some owners advocate free-feeding, which I am sure works well for them and their ferrets, but the more I compare notes with different ferreters, the more I am coming to the conclusion that the best method is in direct comparison with feeding a hawk, that is, to feed to suit the day ahead, as noted above. After practising both free-feeding and specific feeding for a few years, I have learnt from my own experiences which best suits my methods and ferrets. However, the individuality of ferrets and ferreters ensures that what suits me will not necessarily suit you, so if you are happy with your personal set-up and arrangements, stay with them.

There is a world of difference between feeding to suit the needs of the day and starvation. The object is to have a keen, enthusiastic and ft ferret for the work ahead, not a weakened, famished one. If you starve an animal for any length of time, it dies, simple as that. In the past, the ferret was fed a poor diet at home, so that when it came across succulent meat under the ground it couldn’t resist it, but the end result would be counter-productive, as the ferret would gorge itself and then sleep it off.

Today, the ferret is fed a quality diet of fresh rabbit in the winter months or twelve months of the year if possible. The ferret thus becomes accustomed to the smell, taste and texture of the rabbit, so that when they meet underground, they are no longer strangers. What happens to many ferrets when they have been denied this regular experience with the rabbit, especially with its jacket on, is that they do not fully understand just what a rabbit is and what it means. Instinct will drive the ferret on to hunt, but when the rabbit is cornered in a stop end, for instance, if the ferret does not truly understand that the rabbit is its quarry it will go through the motions and eventually come off the live rabbit as the incentive isn’t there.

Once the ferret truly understands what the rabbit is, it will try to bolt it, sticking with it and trying to kill it. If successful, the ferret doesn’t stay there and eat the rabbit, it simply moves on in search of others. However, take the same dead rabbit and put it in the ferrets’ hutch or court and they are on it like a shoal of piranhas. The well-trained and fed ferret seems to understand the nature of the rabbit in different environments. Of course, ferrets will sometimes start to eat the soft tissue on a recently killed rabbit, such as the eyes or the area of neck it has bitten to kill the rabbit, but on the whole, they move on in search of more prey. In order to carry out successfully the regime of feeding for the day ahead, you must know your ferrets. Too little food and they will fade over the coming hours; too much and they will just go through the motions and miss that extra nip required to perform to their full potential.

The complete ferret (pellet) food is a revolutionary breakthrough for the ferrets’ needs, especially in the warmer months when flies can cause havoc with raw meat. The invention of dried food has given us a healthy and nutritional alternative if required, especially enabling the ferret to be enjoyed as a pet without the owners having to feed, handle or store raw meat, but it is not a substitute for the working ferret’s natural diet, the rabbit. My personal experiences have led me to feed pellets when necessary in the summer months, but when I can, and especially with the young kits, I feed the rabbit in all its glory, fur, meat and bone.

When feeding the ferrets, the amount of food is governed by the number of ferrets kept and their level of activity, as a more active animal will eat more. The ferret requires a balanced and high-quality diet, which usually is either a complete dry food specially designed for ferrets or a raw meat-based diet (rabbit, pigeon and so on) or a combination of the two. If feeding one of the many ferret complete diets (biscuit), follow the feeding guidelines on the packaging but remember that these are guides only. Although some ferrets are smaller than others, a half a mug full of ferret food in a plastic bowl should be suffice for two ferrets a day. The food will be eaten over many sittings and is fed ad lib, but if you notice some ferrets, especially hobs, sitting by the bowl and eating too much, just feed and remove the food after a couple of hours. Biscuit does appear to put a little more weight on a ferret than rabbit meat, due to the rabbit’s natural leanness.