20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

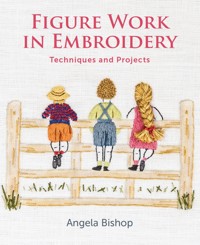

Figures can bring an embroidery to life, but they are tricky to do well. This book guides you through the materials, stitches, body parts and clothes to give you the confidence and skills to embroider a figure and experiment, using your creative inspiration. With over 400 colour photographs it gives key information for getting started, creating designs and preparing embroideries; techniques for making three-dimensional forms using stitching and padding techniques; clear instruction for mastering stitches and then ideas for using them creatively. Specific advice is given for embroidering the face, hair, hands and feet as well as ideas for using stitching embellishments, such as beads, sequins, buttons, ribbons, feathers and jewellery charms. Step-by-step projects demonstrate a range of beautiful styles and techniques.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 234

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

FIGURE WORKIN EMBROIDERY

Techniques and projects

FIGURE WORKIN EMBROIDERY

Techniques and projects

Angela Bishop

First published in 2020 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 2HR

This e-book first published in 2020

©Angela Bishop 2020

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 728 6

The book is dedicated to my mumand my sister for always supportingand encouraging my creative pursuits.

CONTENTS

Introduction

CHAPTER 1 Inspiration and Design

CHAPTER 2 Materials and Equipment

CHAPTER 3 Preparation Techniques

CHAPTER 4 Embroidery Techniques

CHAPTER 5 Stitching Techniques

CHAPTER 6 Embroidering Faces

CHAPTER 7 Embroidering Hair

CHAPTER 8 Embroidering Hands and Feet

CHAPTER 9 Embroidering Clothes and Accessories

CHAPTER 10 Simple Projects

CHAPTER 11 Advanced Projects

CHAPTER 12 Finishing Your Work

Appendix

Further Reading

Acknowledgements

Index

INTRODUCTION

EMBROIDERED FIGURES THROUGHOUT HISTORY

Embroidery is one of man’s oldest skills. Throughout history, embroidery has been used to create art with needle and thread, showcasing designs that would capture a scene from the time it was created, or with symbolic significance. The earliest embroidery is thought to be of Chinese heritage due to the cultivation of silk some 5,000 years ago; Western embroidery can only be traced back to the Middle Ages.

Due to the delicate and fragile nature of the materials used for embroidery, many historical pieces have been lost through poor preservation. Those that remain often include sophisticated designs, sometimes incorporating human figures.

Stitching a stumpwork figure in my studio.

One of the earliest surviving embroideries is a linen roundel dating back to the sixth to eighth century ce, which was found at an Egyptian burial ground; it is a design that portrays the Annunciation and Visitation with four naively designed figures. During 1827 in Durham Cathedral a stole and maniple dating back to the tenth century was discovered in the tomb of St Cuthbert, with an embroidery of a saint intricately stitched in gold and silk. Perhaps the most famous surviving embroidery from the early Middle Ages is the Bayeux Tapestry.

I will briefly describe some of the popular embroideries that can be seen in museums today – both historical and more contemporary pieces – which represent embroidered figures in different techniques.

The Bayeux Tapestry

Housed in Normandy, France, the Bayeux Tapestry is a 70m-long and 50cm-high embroidered narrative wall hanging commemorating the Norman Conquest of Britain, including the Battle of Hastings. Narrative historical hangings were a part of European embroidery tradition in the Middle Ages, but many have not survived.

The Bayeux Tapestry is made up of joined sections of simple needlework. It is thought to be of English workmanship and probably stitched by professional embroiderers. It is worked on a linen fabric using eight shades of coloured two-ply wools – yellows, greens, blues and terracotta reds – and is an impressive example of some six hundred embroidered figures. It is not a tapestry as it is not a woven textile. It is in fact the oldest surviving example of crewelwork embroidery (wool embroidery).

The characters are naïve and slightly obscure in design and is stitched using laid stitches for filling stitches, couching for outlines and stem stitch for details and lettering. The needlework serves as a historical document recording different types of clothing, daily activities such as farming, hunting and cooking, and even records the appearance of Halley’s Comet. The figures are generally designed in profile with simple facial features and more detailed clothing. This embroidery has become the inspiration for many other embroidery projects over time.

A panel of opus anglicanum with Mary Magdalene and a male prophet, England, c.1400. Dimensions: 32.7 × 19.5cm. Courtesy of Sam Fogg, London.

Opus anglicanum

Opus anglicanum (meaning ‘English work’) refers to work of the Middle Ages when English embroidery enjoyed international fame for its highly skilled, widely admired and technical proficiency in embroidered textiles fit for royalty and the clergy. Generally worked in high-quality silks, threads made from precious metals and jewels, the designs of this era famously showcase figures of saints and prophets intricately stitched in split-stitch shading. Fine details of faces, hands and feet are stitched in silk, with clothing often stitched in metal threads using the ‘underside couching’ technique that was invented in this era by the skilled embroiderers.

Embroidered items from this era are primarily ecclesiastical and some still survive today. The Victoria and Albert Museum recently exhibited one of the largest displays of opus anglicanum pieces. This exhibition dazzled the trained and untrained eye to the magnificence of the skills shown in this era, many of the items showcasing technical excellence in embroidered figures.

The Lady and the Unicorn tapestries

These five large artworks are true tapestries, as they are woven. Little is known about who produced them, but it is believed they were designed and constructed in the fifteenth century in France. Housed at the Musée de Cluny in Paris, I was fortunate enough to see them on a visit to Sydney when they were being displayed at the New South Wales Art Gallery. A tapestry is a woven fabric, where a loom is set up with dozens of warp threads (vertical threads) and woven with weft threads, which follow a colour drawing design underneath called a cartoon.

Considering how old these textiles are, the colours of the threads have withstood the test of time, with some conservation evident in areas. The colour combination of gold, burnt oranges, dusky blues and creams all blend well, giving these pieces a lavish feel. It is the intricate details of facial features, hair, hands and clothing the weaver has portrayed, which makes these tapestries so unique and beautiful.

Raised work

This popular form of embroidery during the seventeenth century (today we call it stumpwork), sometimes referred to as domestic embroidery, often contained figures in the designs of panels, boxes, caskets and mirror surrounds. Many of these items were worked by young girls, demonstrating their embroidery skills, and contained figurative characters dressed in costume. Popular themes included biblical figures; myths and legends; royalty or people of significance; and commemorative events.

Arts and Crafts embroideries

During the Arts and Crafts movement in the nineteenth century, following the counted thread technique of Berlin wool work, William Morris popularized the new needlework technique emphasizing delicate shading using satin and long and short stitches (today we call this silk shading). Known more for his decorative floral designs, a set of early embroideries consisted of twelve female figures used to adorn a house interior that was to be Morris’s marital home. These embroideries were designed to replicate the kind of tapestries designed for medieval buildings; thus crewel wool was used instead of silk. The panels were not all completed, but for those that were, the embroidery was worked on linen, cut out and applied to panels of embroidered wool.

Following the trend Morris began, other artists including Edward Burne-Jones, Selwyn Image and Walter Crane produced embroidered figure designs of pre-Raphaelite style muses and goddesses for silk embroidery, many worked by the Royal School of Art Needlework.

Mater Inviolata (Mother inviolate). © Royal School of Needlework, Photography John Chase, Design Ezio Annicini.

Litany of Loreto embroideries

The origins of these twelve embroideries are a mystery, but their design shows the influence of the pre-Raphaelite art movement and they are part of the Royal School of Needlework collection. Each representing an invocation of the Virgin Mary, these embroideries are stitched mostly in long and short stitch and worked on a rich cream satin background, using shades of beige, brown and white silks and enriched with gold threads, showcasing such technical detail that is difficult to comprehend how these artworks have been created.

Little is known about who designed or stitched these treasured art embroideries, but they are perhaps some of the most exquisite embroideries ever created and a beautiful display of embroidered figures.

Panel 4 of the Overlord Embroidery. ©The D-Day Story, Portsmouth UK.

Overlord Embroidery

The Overlord Embroidery is an impressive display of thirty-four embroidered panels, each measuring 2.4m long and 90cm deep. It is a modern-day narrative hanging displayed at the D-Day exhibition in Portsmouth, England. Inspired by the Bayeux tapestry, each panel tells a story about the D-Day landings in Normandy during the Second World War and captures the mood remarkably. Designed by artist Sandra Lawrence and commissioned by Lord Dulverton of Barsford, this embroidery was worked by twenty embroiderers and five apprentices from the Royal School of Needlework, taking five years to complete in the early 1970s.

This embroidery was worked using mainly appliqué techniques and surface stitching. More than fifty different materials were used, including 320m of cording. Much of the design displays appliquéd figures with different thicknesses of padding and layers of sheer fabrics to create colour definition in skin tones and three-dimensional form, creating contours of facial features and body parts. Eyes and lips have been defined using different appliqué methods, some having detail of colour stitched using satin stitch and long and short stitch to create eyebrow and lips. This is a remarkable piece of modern embroidery.

The Quaker Tapestry

The Quaker Tapestry is a series of seventy-seven stitched and framed narrative embroideries displaying three hundred years of Quaker insights and experiences. Housed at the Friends Meeting House in Kendal, Cumbria, the Quaker Tapestry is a crewelwork embroidery worked on specially woven woollen cloth. Inspired by the Bayeux Tapestry, this is the legacy of Anne Wynn-Wilson who had the vision to create this unique embroidery. It became an international community project involving 4,000 people from fifteen countries placing a stitch or two into a panel and managed by 300 embroiderers carrying out the main part of the work. The whole project took fifteen years to complete.

Each panel has been stitched by different volunteer groups from around the world and demonstrates some charming embroidered figures in most of the panels. Worked in 2-ply crewel wool, most of the faces are stitched using the base fabric as skin tone with outlined facial features and the clothing, displaying a selection of surface stitches mixed in a creative way giving texture and detail to the designs.

Figures have often been a part of embroidery designs through history but are frequently avoided by novice embroiderers due to a lack of confidence in being able to replicate one favourably. I have written this book to give you the inspiration, knowledge and courage to embroider a figure and experiment using your creative stash.

This panel is called World Conference 1991 and is one of seventy-seven panels known as the Quaker Tapestry. It is a modern community embroidery made by 4,000 people from fifteen countries. The exhibition of panels can be seen at the Quaker Tapestry Museum in the Friends Meeting House in Kendal, Cumbria, UK.

CHAPTER 1

INSPIRATION AND DESIGN

During my studies with the Royal School of Needlework, I gathered inspiration from a variety of sources: fashion and tabloid magazines; historical books; costume books; dressmaking patterns; greetings cards; artworks; fashion catalogues; Pinterest; Instagram; Google searches; photographs; museum exhibitions and displays; the list is endless. We are surrounded by people on a daily basis, so finding source material is not difficult for an embroidered figure project.

It is good practice to organize your inspiration material in the form of a sketchbook. Some textile artists make very creative sketchbooks and they can be an artwork in their own right. I tend to organize my inspiration in themes and stick pictures, fabric and threads in a sketch book, and sometimes scribble ideas as I do this, so I can refer back to my ideas at a later date.

When looking at subject matter, I am inspired by fashion eras, particularly the 1920s. I find the style, glitz and glamour of the era inspirational, enabling me to create fun embroideries that suit my theme of ‘stash-busting’, where I can create a project with mixed embroidery techniques and supplies.

Preparing a figure embroidery design.

CREATING YOUR OWN WORK

Thinking about designing an embroidery project can be overwhelming and often the idea of including a figure can be a daunting prospect when compared to thinking about a design with flora, fauna or architecture, but completing your own design with a figure that has a meaning for you can be very rewarding.

When you design an embroidery project there are key decisions you need to make and plan for before you start stitching. This thought and planning process, referred to as an ‘order of work’ will make the whole project easier and less daunting. Your project will then be better planned, less stressful and eliminate too many mistakes or ‘reverse stitching’. Some aspects to consider are:

What item do you want to create? Is it a functional item like a bag? A book-cover, or a picture?

If you are designing a picture, is it for a site-specific place? A present? An exhibition?

What figure do you wish to embroider?

What technique or techniques do you wish to include?

What items in your ‘stash’ do you wish to use?

What colour scheme do you want to stitch the project in?

Does the design have historical context or is it stylized?

What background fabric do you want to use? A printed fabric? Hand-dyed fabric? Fabric you have created? Plain fabric?

How will you embroider the piece? In an embroidery hoop? Slate frame? In your hand?

Does this piece need to be completed by a specific time? If so, be aware of how much time you can devote to the project and allow extra time for sampling or ‘reverse stitching’ in case things don’t work out the first time.

Where will you be stitching this piece? In the same work area or in different places? This will dictate the size and scale of what you might create.

Design something that is achievable and that you will enjoy. There is nothing worse than creating something that you do not enjoy or was too ambitious.

DESIGNING A FIGURE PROJECT

When designing a figure project, think about the anatomy of a human body and the basic body proportions. There are numerous guidebooks, videos and diagrams offering recommendations on how to draw a human body and its parts. I know embroidering a human figure is not the same as drawing, but during the design process, drawing an accurate design is key to producing an attractive embroidery project. I have researched many suggestions and ‘how to’ guides on drawing figures and although most are similar, there are some suggestions that resonate for me when thinking about how to stitch a realistic figure. If your figure is going to be more cartoon-like, emphasize some of the body parts to give it a less realistic appearance.

I find by tracing pictures of people from the source material I have it becomes easier to see different shapes and poses in figures and gives you a better understanding and more confidence in drawing a figure and its parts. I will share with you some of the guidelines I have found useful.

This stick figure diagram shows the standard proportions of a human body. Notice how the figure is equally divided into eight portions, giving a simple guide when drawing a human body in correct proportion.

THE HUMAN BODY

As a general rule, the human body is equivalent to seven-and-a-half to eight heads tall. When drawing a figure, it is often best to use the measurement of eight heads, making it easier to create alignments of body parts. I will present a diagram demonstrating how the human body is proportioned.

When drawing a figure, if what you have drawn does not look quite right, think about the proportions of the body parts and check that they are correct to make the figure appear natural. If you want your figure to be stylized or cartoon-like, think about how you draw these natural proportions differently to create a unique character. A good example of this is in graphic novels: figures are drawn with exaggerated heads, facial features or smaller bodies which are not of normal proportion, and this gives them a unique character.

This diagram shows the proportions of a ‘child’s pose,’ demonstrating how the human body almost fits into three equal parts.

Body proportions

•The torso is equal to the upper leg, the lower leg or the arms without hands.

•The forearms (elbow to fingertips) is equal to the gap between the knee and the heel.

•The forearm stretched (elbow to wrist) is equal to the foot.

•The forearm when bent looks shorter and the distance from inside the elbow to wrist is equal to a hand.

•Elbows generally sit at waist level.

•Wrists usually line up with the top of the thigh.

•Knees are generally halfway between the thigh gap and ankle.

The face

A face is such an important feature of the human body. The face presents the finer features that give a head its character. It is the most challenging part of the body to get right when drawing or painting, but probably even more difficult in embroidery due to the scale and the media being used. Creating the fine, curved features that a face has is not the easiest task with needle and thread, but with careful planning it can be possible.

The size of a figure dictates the size of the head, and if the figure is small so is the head; now the challenge is to decide how much detail to include in your design. Scale is key to making a face look as realistic as possible. When looking at embroidered figures, look closely to identify which features are included. Embroidered techniques such as stumpwork add detail to faces very precisely, creating a three-dimensional face by stitching filled fabric slips in such a way as to mould the padding to replicate a face accurately. Surface embroidery will also allow the embroiderer to create detailed facial features, by carefully selecting stitches and thickness of threads used. These will be demonstrated later in the book.

In the same manner as drawing a body, a human face has similar guidelines of proportions; if followed, they will give a realistic result. I will demonstrate this with the following diagram.

Hands and feet

Hands and feet can be created in embroidery in a few different ways. Like a face, the scale of the figure you are designing will dictate how much detail can be achieved. Feet are perhaps slightly easier, as you can consider adding footwear, but hands are not always straightforward. When looking at ecclesiastical embroideries, some of the details in hands and feet are incredibly realistic. This is achieved using the thread painting technique: coloured threads are carefully selected and mixed together to create shading, giving the result of realistic hands and feet. An experienced embroiderer can achieve this with close study of the colours and tones of thread. I will demonstrate alternative ways to include hands and feet later in the book.

Clothing

In a figurework project, clothing is perhaps where your creativity and stash can really be explored and utilized. Adding different fabrics, embellishments, making your own textile creation, using the background fabric you have chosen, will all add to the fun of dressing your figure. Padding underneath the clothing can also be considered to give the look you want to achieve. When considering a stumpwork figure, all body features have some three-dimensional form, but in appliqué, consider padding only underneath the clothing. Using the example of ecclesiastical figures, clothing is stitched to give a realistic three-dimensional finish in the same manner as the features of the body.

DESIGN COMPOSITION

Once you have chosen the item you are stitching and the figure you wish to include, think about the composition of your project:

What will the figure be doing?

Is there a location you wish to portray in your design as the background?

Will the figure be a feature in its own right and be stitched on a plain background?

What is the size and scale of the project?

What colours and textures will be included?

Is the figure the focal point of the design?

Facial features and proportions

•Eyes are set halfway between the hairline and the chin.

•The two eyes have the width of one between the two.

•The top of the ear is level with the eyes (men’s ears are usually larger than women’s).

•The bottom of the nose is halfway between the eyes and the chin.

•The mouth is halfway between the nose and the chin.

When asking yourself these questions you are considering the basic elements such as line, shape, colour and texture, which then leads to the principles of design: balance, proportion, emphasis, contrast, movement, pattern and unity. There are numerous books and online sources that show what ‘correct’ design is, but often our own eye tells us when a design is not quite right. If this is the case, don’t ignore it. You may need to work on the design more in order to perfect what you are creating. A good composition gives natural balance, leads the viewer’s eye to the image and draws attention to the important parts of the scene being created.

Many people find the design process challenging and hard work, which deters them from doing their own bespoke pieces. Don’t be disheartened: designing takes practice. Ask fellow embroiderers what they would suggest, do lots of research by looking at galleries to see how artists compose their artworks, and look at the work of other embroiderers and textile artists at shows or on their websites to see how they design a piece. Pinterest and Instagram are good online sources where artists show their work. Choose a topic, e.g. ballerina, and see how people have portrayed ballerinas in an artwork or embroidery. Such sources of inspiration are endless and can really stir up your creative juices.

When drawing a face, follow these guidelines to give a realistic result.

A grid showing the rule of thirds. Place the feature elements of your design within the intersecting points of the vertical and horizontal lines.

When designing a project, the techniques you consider may be determined by the instructions you have been given, or perhaps the subject would work well with a particular stitching technique. If this is not the case, as you are thinking about your design and layout, this is often a good time to consider searching through your stash to inspire you with textures, colours, threads, fabrics and embellishments that you may wish to include in your project.

When composing a figure design, think about the following to help you create an eye-catching piece:

Choose your format – round, square, rectangle, for example.

Consider the ‘rule of thirds.’ If the focal point (in this case a figure) is placed at the centre of the design area, it will split the picture up. If the focal point is off centre, this will balance and add interest to the picture, drawing the eye into the composition.

Divide the design area into nine equal blocks. The intersections of the lines are the points to consider placing your feature. If you are considering a horizon, place this on the top or bottom lines, never in the middle of the design area.

Think about objects in the foreground, overlapping objects, or obscuring features to create some depth and interest.

To fine-tune your design, create a line drawing of what you will be stitching, place the drawing in a location you often walk past and leave it here for a day or two. As you walk past it you will be unconsciously looking at it and your eye will draw attention to what is right or wrong with the design. Touch up areas you wish to improve and then commit to what you have put together.

COLOUR PLAN

Once your line drawing is complete, think about a colour plan. You may have already chosen your colours when searching through your stash but have not decided where on your design you will use which colour. Gather a selection of coloured pencils or paint and colour your line drawing in a couple of different ways to see which appeals the most. As you colour your drawing, think about light and dark areas; paying attention to the tones of colour in your design will help give your composition some balance and a realistic appearance.

If selecting colours for your project is daunting, and the words ‘colour theory’ cause fear, look around in your familiar surrounds and see what colours you have in your wardrobe or around your house. We have a natural affinity with colours without really being aware of this. When we choose our clothing or soft furnishings, we usually purchase what our eye was naturally drawn to when searching for what we wanted to buy. One way to understand how colours work together is to look in clothing shops and see how the colours in the printed fabrics are mixed together. This is also the case with soft furnishings – curtain fabrics, rugs, wallpapers are all resources that you can look at for inspiration in colour selection. Fashion and home magazines are also an excellent resource for looking at how colours can be combined.

Colour theory

Colour theory simply describes how colours work together. Many books have been written about colour theory, which explain to varying degrees how colours work with each other. There are basic ‘rules’ set out to explain the different ways colours can be mixed, but as with most rules, these can be altered or ignored. A useful resource for any artist is a colour wheel to help you understand the principles and reason why some colours work together and others do not.

Sir Isaac Newton invented the first colour wheel in the mid-1600s, during his work with white light. He discovered the visible spectrum of light by passing light through a prism, which led him to identify the colours red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo and violet. These colours naturally exist when we see a rainbow.

Primary colour stranded cottons: yellow, blue, red.

Primary colours: yellow, blue and red

These are the basic colours used to create all other colours. They cannot be created from other colours, as they are pure pigments.

Secondary colour stranded cottons: orange, green, violet.

Secondary colours: orange, green and violet

These colours are made by mixing two primary colours together.

Tertiary colours

Tertiary colours are made by mixing a primary and secondary colour together.

Looking at colours on the colour wheel and the way they lie next to each other will help you decide how harmoniously the colours you choose will work in your project. We refer to these colours as ‘complementary’ and ‘analogue’.

Complementary colours

These colours lie directly opposite each other on the colour wheel and generally work well together, creating interesting contrasts. When used together they will balance and harmonize in your design depending on their light intensity. The chart below shows the amount of each colour needed to balance with each other in order to be harmonious.

This demonstrates the quantities of colours used to harmonize in a design when creating contrasts.

Analogue colours

These colours sit side by side on the colour wheel, giving a calm colour scheme.

Other terms to understand when considering colour theory include:

Tint: a colour with white added, making it look lighter.

Shade: a colour with black added, making it look darker.

Tone: this refers to the brightness of a colour, how light or dark a colour is. It is colour with grey added. On an extreme scale, black is the darkest and white the lightest of colours.

Warm colours: generally reds, oranges, and yellows, but can be other colours that are vivid and appear to be coming towards you.

Cool colours: generally blues and greens, but can be other calming colours that recede from you.

Monochrome colours: tints of one colour; a tonal scale of a colour.