Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

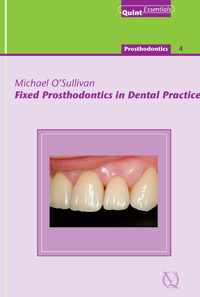

- Herausgeber: Quintessence Publishing Co. Ltd.

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Serie: QuintEssentials of Dental Practice

- Sprache: Englisch

The practice of fixed prosthodontics has undergone many changes in recent times with significant developments in dental materials and principles of adhesion. However, tooth preparation is still guided by the need to preserve tooth tissue, generate space for restorative material and reshape the tooth to a cylindrical form with a defined finish line. This book carries these principles as a common theme and delineates the stages of prosthesis construction.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 190

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Quintessentials of Dental Practice – 22Prosthodontics – 4

Fixed Prosthodontics in Dental Practice

Author:

Michael O’Sullivan

Editors:

Nairn H F Wilson

P Finbarr Allen

Quintessence Publishing Co. Ltd.

London, Berlin, Chicago, Paris, Milan, Barcelona, Istanbul, São Paulo, Tokyo, New Delhi, Moscow, Prague, Warsaw

British Library Cataloguing-in Publication Data

O’Sullivan, Michael Fixed prosthodontics in dental practice. - (Quintessentials of dental practice; 22. Prosthodontics; 4) 1. Prosthodontics I. Title II. Wilson, Nairn H. F. III. Allen, P. Finbarr 617.6′9

ISBN 185097330x

Copyright © 2005 Quintessence Publishing Co. Ltd., London

All rights reserved. This book or any part thereof may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 1-85097-330-x

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright Page

Foreword

Preface

Acknowledgements

Contributors

Chapter 1 Patient Assessment and Presentation of Treatment Options

Aim

Outcome

Introduction

Patient History

Dental Examination

Special Tests

Mechanics

Micromechanics

Macromechanics

Aesthetic Considerations

Risk Analysis

Diagnostic Wax-Up

Contingency Planning

Conclusion

Further Reading

Chapter 2 Objectives of Tooth Preparation

Aim

Outcome

Concepts and Principles

Preparation Objectives

Biological Considerations

Pulp Health and Tissue Conservation

Adjacent Tissues

Mechanical Considerations

Retention and Resistance Form

Mechanical Preparation Guidelines

Finish Line

Aesthetic Considerations

Conclusion

Further Reading

Chapter 3 Restorative Periodontal Interface

Aim

Outcome

Biological Width

Periodontal Restorative Interface in Restorative Dentistry

Restorative Margin Placement

Treatment of Marginal Tissues During Impression-Making

Surgical Procedures to Enhance Restorative Outcomes

Crown-Lengthening Surgery

Definition

Indications

Assessment

Technique

Healing

Grafts

Free Gingival Grafts

Definition

Indications

Assessment

Connective Tissue Graft

Definition

Indications

Assessment

Conclusions

Further Reading

Chapter 4 Provisional Restorations

Aim

Outcome

Introduction

Biological Factors

Pulpal Health

Gingival Factors

Diagnostic-Gingival

Therapeutic

Thermal

Mechanical

Aesthetic and Diagnostic

Provisional technique

Classification

Provisional Technique

Direct Technique

Indirect Technique

Combined Technique

Technique Selection Factors

Reline Materials

Conclusions

Further Reading

Chapter 5 Impression-Making and Gingival Manipulation

Aim

Outcome

Tissue Preparation

Tissue Health

Location of Finish Line

Technique

Impression-Making

Gingival Displacement

Mechanical

Mechanochemical

Rotary Gingival Curettage

Electrosurgery

Haemostatic Agents

Field Control

Impression Trays and Materials

Conclusion

Further Reading

Chapter 6 Clinical Maxillomandibular Relationships and Dental Articulators

Aim

Outcome

Maxillomandibular Relationship Records

Maximum Intercusping Position

Centric Maxillomandibular Relation

Clinical Techniques to Record Mandibular Relationships

Dental Articulators

Simple Hinge Articulators

Plane-Line Articulators

Adjustable Articulators

Semi-Adjustable Instruments

Fully Adjustable or Highly Adjustable Articulators

Setting the Maxillary Cast in the Articulator

Placing the Mandibular Cast in the Articulator

Mounting Casts of Dentate Arches Accurately in MIP

Index Method to Mount Casts in MIP

Reference Position Based on CMA Relationships

Preparing the Wax Pattern (Figs 6-10 to 6-12).

Checking the Mounted Relationship of the Casts

Materials for Making Inter-Occlusal Records

Materials

Waxes

Hard Dental Wax

Baseplate Wax

Polyvinyl Siloxane Interocclusal Recording Materials

Conclusion

Further Reading

Chapter 7 Shade Selection in Fixed Prosthodontics

Aim

Outcome

Introduction

Colour

Common Lighting Errors in Colour-Recording

Interference from Other Colours

The Object

Prescribing and Communicating Colour

Language

Hue

Chroma

Value

Communication of Colour

Diagram and Shade Tabs

Related Factors to Consider

Technique for Using a Shade Guide

Limitations of shade guides include:

Photograph or Slide Images

Meeting the Ceramist

Future Developments

Application of Colour Principles to Dental Porcelain

Surface Considerations

Altering Value and Chroma

Conclusion

Further Reading

Chapter 8 Evaluation of Completed Restorations

Aim

Outcome

Initial Assessment

Design of Restoration

Polish and Finish of Restoration

Marginal Integrity

Restoration Contours

Individual Surfaces

Buccal

Lingual

Mesial and Distal

Contact Relations and Embrasures

Intra-Arch Features

Arch Form

Occlusal Plane

Inter-Arch Features

MIP Contacts

Contacts on Lateral Movements

Horizontal and Vertical Overlaps

Access for Cleaning

Clinical Assessment

Marginal Integrity

Occlusal and Arch Relations

Colour-Matching

Conclusion

Further Reading

Chapter 9 Selection and Use of Luting Cements: A Practical Guide

Aim

Outcome

Introduction

Handling Properties

Physical Properties

Adhesion

Mechanical Properties

Biological Properties

Water-Based Cements

Zinc Phosphate Cement

Mizzy’s Flecks Cement®, Tenacin®

Mechanical Properties

Biological Properties

Physical Properties

Ease of Use

Polycarboxylate Cement

Poly-C®, Poly-F®, Durelon®.

Mechanical Properties

Biological Properties

Physical Properties

Ease of Use

Glass Ionomer (Glass Poly-Alkenoate) Cement

Ketac-Cem®, Aqua-Cem®

Mechanical Properties

Biological Properties

Physical Properties

Ease of Use

Resin-Based Cements

Crown and Bridge Metabond®, Panavia Ex®, Panavia F® and Variolink®, Calibra®, Nexus®

Mechanical Properties

Physical Properties

Biological Properties

Ease of Use

Restorative Substrate Preparation

Ceramic Materials

Metallic Materials

Compomer and Novel Cements

Dyract Cem®, RelyX-Cem®

Resin-Modified Glass Ionomer Cements

Vitremer Lute®, Fuji Plus®

Mechanical Properties

Physical Properties

Biological Properties

Ease of Use

Provisional or Temporary Luting Agents

Zinc Oxide and Eugenol Cements

Tempbond®, Tempak®

Non-Eugenol Cements

No-Genol®

Polycarboxylate Cement

Ultratemp®

Conclusion

Further Reading

Chapter 10 Resin-Bonded Restorations

Aim

Outcome

Tooth-Related Factors

Amount of Available Enamel for Bonding

Occlusal Loading

Resin Luting Agents

Types

Accuracy of Fit

Cement Lute Thickness

RBFPD Design and Tooth Preparation

Design of Metal Frameworks

Prosthesis Rigidity

Groove Placement

Parallelism of Preparations

Preparation Design

Posterior Design (Fig 10-3 and Fig 10-4)

Anterior Design (Fig 10-3 and Fig 10-4)

Number of Abutments and Pontics

Cantilever Resin-Bonded FPDs

Conclusions

Further Reading

Chapter 11 Restoration of Non-Vital Teeth

Aim

Outcome

Diagnostic Considerations for the Restoration of Non-Vital Teeth

Selection of the Restoration for a Non-Vital Tooth

Anterior Teeth

Endodontically Treated Anterior Teeth

Does the Tooth Need a Crown?

Sealing the Root Canal

Internal Bleaching

Does the Tooth Need a Post and Core?

What Type of Post and Core should I Use?

Tooth Preparation for Post and Core

Impression for a Post and Core

Direct Technique (Fig 11-8)

Indirect Technique

Cementation of Endodontic Posts

Direct Post and Core

Posterior Teeth

Axial Walls Mainly Intact

Technique

Moderate Loss of Coronal Structure

Technique

Severe Loss of Coronal Structure

Technique

Conclusion

Further Reading

Foreword

Good quality, aesthetically pleasing fixed prosthodontics that fulfil patient expectations are a potent, professionally rewarding practice builder. Achieving consistently high standards in fixed prosthodontics is, however, a substantial challenge, even for the experienced practitioner. This challenge may be best managed by having a good understanding of the evolving principles of modern fixed prosthodontics, underpinned by up-to-date knowledge of contemporary techniques and relevant materials.

Fixed Prosthodontics in Dental Practice, Volume 22 of the timely Quintessentials of Dental Practice series, meets this need. It is not intended to be a comprehensive tome; it is a succinct, authoritative overview of the key elements of fixed prosthodontics, with a focus on achieving good clinical outcomes. This book, in common with all the other volumes of the Quintessentials series, makes easy reading over an evening or two and has been prepared in a style to encourage readers to rethink their current approach – in this case, to fixed prosthodontics. From patient assessment through to the evaluation of completed restorations, this carefully crafted, attractively illustrated, multi-author text provides sound, evidence-based guidance, tempered by a wealth of experience shared by experts in the field.

This book provides new insight for students of all ages – yet another excellent addition to the very popular and rapidly expanding Quintessentials of Dental Practice series.

Nairn Wilson Editor-in-Chief

Preface

The practice of fixed prosthodontics has undergone many changes in recent times, with significant developments in dental materials and principles of adhesion. However, tooth preparation is still guided by the need to preserve tooth tissue, generate space for restorative material and reshape the tooth to a cylindrical form with a defined finish line. This book carries these principles as a common theme and delineates how it influences the steps of prosthesis construction.

It is intended to act as a guide that supplements existing prosthodontic knowledge and focuses on areas that are traditionally covered in less detail, such as assessment, shade-taking, assessment of completed restorations and decision-making for restoration of non-vital teeth.

It is hoped that having read this book the reader will have an increased understanding of:

The importance of patient assessment, with emphasis on assessment of abutments, edentulous spaces and occlusal forces.

Principles of preparation and how restorative space will have a significant impact on the success of both conventional and adhesive prostheses.

How periodontal factors and operating field control can enhance prosthetic outcomes.

The importance and multiple functions of provisional prostheses.

How correct simulation of maxillo-mandibular relations can improve the final prosthesis and reduce clinical time spent adjusting restorations.

The challenges of colour-matching ceramics and how to improve colour communication with the dental technician.

How to evaluate a completed prosthesis in a step-wise fashion.

How to choose a luting agent.

Decision-making in restoring endodontically treated teeth.

Michael O’Sullivan

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my colleagues at the Dublin Dental Hospital for their support in the preparation of this book. In particular I would like to thank Dr. Finbarr Allen for his editorial assistance and Professor Liam McDevitt, Dr. Frank Quinn and Professor Brian O’Connell for their ideas and encouragement. I would like to thank all the contributors to the individual chapters who toiled without complaint. The authors reflect a wide spectrum of prosthodontic backgrounds, which is helpful in establishing a consensus of opinion.

Finally I would like to thank Noreen, Fionn and Joe for their collective proof-reading and patience over the time it has taken to complete this book.

Contributors

Dr. Michael O’Sullivan

Senior Lecturer /Consultant, Department of Restorative Dentistry & Periodontology, Dublin Dental School & Hospital, Dublin, Ireland

Edward G. Owens

Private practitioner, practice limited to prosthodontics, Dublin 6

Dr. Paul Quinlan

Lecturer, Department of Restorative Dentistry & Periodontology, Dublin Dental School & Hospital, Dublin, Ireland and Private practitioner, practice limited to prosthodontics, Dublin 2

Dr. R. Gerard Cleary

Lecturer, Department of Restorative Dentistry & Periodontology, Dublin Dental School & Hospital, Dublin, Ireland and Private practitioner, practice limited to prosthodontics, Dublin 4

Dr. Kevin O’Boyle

Private practitioner, practice limited to prosthodontics, Dublin 4

Prof William E. McDevitt

Professor /Consultant, Department of Restorative Dentistry & Periodontology, Dublin Dental School & Hospital, Dublin, Ireland

Dr. John Fearon

Postgraduate, Department of Restorative Dentistry & Periodontology, Dublin Dental School & Hospital, Dublin, Ireland

Dr. Frank Quinn

Senior Lecturer /Consultant, Department of Restorative Dentistry & Periodontology, Dublin Dental School & Hospital, Dublin, Ireland

Prof. Brian O’Connell

Professor /Consultant, Department of Restorative Dentistry & Periodontology, Dublin Dental School & Hospital, Dublin, Ireland

Chapter 1

Patient Assessment and Presentation of Treatment Options

Aim

The aim of this chapter is to outline the process from initial patient contact to arrival at a treatment plan. An algorithm is suggested to assist methodical data collection and diagnosis.

Outcome

After reading this chapter, the clinician should be able to provide a framework within which to accumulate and interpret clinical findings in order to formulate a relevant treatment plan for individual patients.

Introduction

During the first consultation, both the patient’s presenting complaint and its history should be recorded in the patient’s own words and be as detailed as possible. The record should act as a focus during examination, and the final treatment option must fully address this complaint. A record must be made of any previous treatment for the same complaint to assist in the analysis of success or failure. A complete patient record consists of three phases:

patient history

dental examination

special tests.

Patient History

A complete patient history should include:

Dental history – a record of past attendance, treatments and associated complications following treatment. It should address any history of trauma and reasons for extraction of teeth. The former is significant as teeth may, as a consequence, be compromised, and the prognosis for treatment involving these teeth can be less favourable. Loss of teeth may be an indicator of caries or periodontal disease susceptibilities and suggest difficulties with replacement of missing teeth from ongoing caries or soft tissue recession and attachment loss.

Medical history – this can be recorded using a variety of methods, but before treatment the following questions must be addressed:

Will any element of the patient’s medical history affect dental treatment?

Will any element of the patient’s dental treatment affect his or her medical status?

Is the patient taking any medication that will affect dental treatment?

Will dental treatments affect the patient’s current medication regimen (including prescription medication)?

Social history – provides a background to the patient and identifies habits (for example, smoking and alcohol consumption) or pastimes (for instance, contact sports or hobbies involving hyperbaric conditions) that may influence treatment options.

Dental Examination

A dental examination should address:

Disease – the first step in preparation for prosthodontic treatment is to identify and eliminate disease in order to establish health. Disease should encompass both past experience and current status.

Periodontal health – a complete periodontal examination identifies the current status of the supporting tissues. Active disease must be addressed prior to prosthodontic treatment. The periodontal examination should also highlight areas that influence treatment outcome, such as teeth with furcation involvement or poor prognosis. The effects of previous periodontal disease should be taken into consideration – in particular, attachment loss and resulting recession, tooth mobility, irregular gingival margin heights and the absence of attached gingivae in any area (see Chapter 3). Effectiveness of home dental care should also be assessed and modified, if necessary, prior to definitive treatment planning (Fig 1-1).

Caries assessment – this should identify existing lesions and restorations present. The number and extent of restorations indicates past caries experience, and location may suggest rampant caries if the mandibular incisors or mandibular lingual surfaces are restored. Based on this exam, a preventative regimen can be targeted to the individual patient’s needs.

Pulpal health – the pulpal health of individual teeth should be assessed if they are heavily restored or have been traumatised. Tests should include cold/hot/electric pulp testing, in addition to percussion and radiographs. Findings from retrospective studies have determined that many prosthodontic failures occurred as a result of having to complete endodontic treatment after placement of the definitive prosthesis, so careful preoperative assessment is necessary. If teeth are endodontically treated, the following questions should be addressed:

Is the tooth restorable?

Are there signs or symptoms of periapical inflammation?

Is there associated pain?

Radiographically is there an intact lamina dura and is there apical bone loss?

If pathology is identified, is it resolving, static or worsening (Fig 1-2)?

Is the canal obturation homogenous, well condensed and extending throughout the length of the canal?

Fig 1-1 Periodontal tissue breakdown, as a result of (a) poor local hygiene or (b) iatrogenic causes.

Fig 1-2 Endodontic treatments must demonstrate resolution of periapical infection prior to restoration of teeth. (a) Pre-op radiograph of tooth 36. (b) Immediate post-op radiograph. (c) Three month post-op recall radiograph, demonstrating resolution of the apical pathology.

If concerns exist about the status of an existing endodontic treatment then re-treatment, or extraction, should be considered.

Mucosal health – the oral mucosa must be healthy before restorative treatment. Loss of mucosal continuity or discomfort must be controlled prior to definitive treatment planning. Such conditions include areas of ulceration or erosion, allergies and altered sensation such as ‘burning mouth syndrome’. Consultation with an oral physician may be required to treat the condition prior to restorative care. If the mucosal condition is not controlled it will cause discomfort during treatment and may hinder oral hygiene procedures, making treatment and its maintenance more difficult.

Craniomandibular articulation (CMA) health – a screening examination for joint derangement and muscle dysfunction must be completed to determine the need for more extensive investigation. The proposed screening exam acts as a good patient record and also brings any functional deficits to attention at an early stage (Table 1-1).

Table 1-1

Craniomandibular articulation health exam

1. Anterior tooth relationships: Class I, II, III (vertical and horizontal overlap).

2. Number of functional units in maximum intercusping position (MIP).

3. History of:

CMA noise, locking, pain

muscle fatigue /discomfort

difficulty in opening mouth, chewing, talking.

4. Tooth measurements.

5. Co-ordination of voluntary movements:

depression: good, poor left lateral: good, poor right lateral: good, poor.

The CMA screening exam should address the following questions:

Does a satisfactory end-stop exist in the MIP? Are there sufficient numbers and distribution of functional units?

Are the overlap relationships/dynamic occlusions/anterior guidance satisfactory? Can they be improved?

Is the patient excessively clenching or grinding the teeth? Does this pose a difficulty for the proposed treatment plan?

Is there evidence of tooth mobility or fremitus? Is there evidence of damage in the dentition as a result of parafunction?

Are teeth/CMA being overloaded?

Is there evidence of intracapsular discomfort/pain during function or during the testing mandibular movements and/or manipulations?

Is the range of mandibular depression and CMA comfort adequate for restorative procedures to be completed on posterior teeth over long treatment sessions?

Is further functional assessment of the CMA status required? If the answer is yes, a more detailed examination/referral to a specialist practitioner is indicated.

Special Tests

Mechanics

Mechanics can be subdivided into micro- and macromechanics. These are best evaluated in conjunction with mounted study casts of the patient.

Micromechanics

Micromechanics are concerned with individual teeth and, in particular, proposed abutments. The strength of any individual crown is primarily determined by the amount of dentine remaining coronal to the finish line. The main features of the preparation include height, width and irregularity and are summarised in Table 1-2.

Table 1-2

The micromechanical factors involved in determining the suitability of a tooth to receive a fixed restoration

Prognosis

Excellent

Unfavourable

Amount of dentine

Intact

Restorations

Post/core

Preparation height

Tall

<3 mm

Preparation width

Narrow

Wide

Preparation irregularity

Irregular

Regular

Root shape

Splayed

Conical

Root length

Long

Short

Attachment level

No attachment loss

Less than 1:1

Height – the greater the distance from the finish line of the preparation to the occlusal surface/incisal edge, the more difficult it is to dislodge an extra-coronal restoration (Fig 1-3). Tipping forces on short preparations will result in poorly tolerated shear stress being placed on the luting agent, while on tall preparations it will result in more favourable compressive loading of the luting agent. Methods of improving preparation height include periodontal crown-lengthening, orthodontic extrusion or moving the finish line apically without encroaching on the biological width.

Width – a narrow preparation has a smaller rotational path of dislodgement than a wider one. The inclusion of auxiliary retention should be borne in mind at the preparation stage. This includes axial slots, grooves and boxes that serve to decrease the radius of the rotational path of dislodgement (width/height relationship).

Irregularity – a symmetrical smooth preparation will resist rotation less than an irregular preparation.

Root structure – longer splayed roots are better able to resist occlusal forces and demonstrate reduced mobility in the event of attachment loss when compared to conical short roots (Fig 1-4). This becomes more critical when the tooth is to be used as an abutment.

Attachment level – the optimal tooth for prosthodontic purposes is one without attachment loss. Any loss is a compromise, in particular if there is a differential in mobility between abutments for a fixed partial denture. Attachment loss may also result in soft tissue loss. It is important to consider this, both aesthetically and from the preparation finish-line perspective, which may be on cementum – thought to be less favourable than preparations ending on enamel. In addition, as the finish line moves apically from the cemento-enamel junction the diameter of the tooth decreases. This may lead to increased risk of pulpal encroachment and the inability to reduce the required tooth tissue for restoration. Surgical crown lengthening may, however, be indicated if insufficient preparation height exists (see Chapter 3).

Fig 1-3 Effect of preparation height on loading of luting agents. Tipping forces on short preparations will result in poorly tolerated shear stress being placed on the luting agent, while on tall preparations will result in more favourable compressive loading of the luting agent.

Fig 1-4 Root structure and attachment level. (a) Longer splayed roots without attachment loss provide preferable support for fixed restorations. (b) Short, conical roots and teeth that have lost attachment may reduce the ability of the tooth to resist occlusal forces, particularly when used as abutment for fixed partial dentures.

Macromechanics

This primarily involves occlusion but also includes edentulous spans in the case of fixed partial dentures. The probable functional and parafunctional occlusal load should be assessed both statically and dynamically. The edentulous span should be assessed under the following headings:

Parallelism of abutments – if the proposed abutments diverge or are rotated, then additional tooth reduction will be required to ensure a common path of insertion. This additional tooth loss may damage the pulp. To manage divergence or convergence, consider a fixed-movable design, elective devitalisation of an abutment or orthodontic alignment.

Length of span – beam law dictates that if the span of a beam is doubled then its flexibility increases eight times. Increasing metal bulk in the restoration or using an alloy with superior mechanical properties (for example, increased proportional limit and modulus of elasticity) will reduce flexure. To facilitate an appropriate pontic form, the dimensions of the edentulous span should be appropriate for the tooth/teeth being replaced. This is best assessed using a diagnostic wax-up. Orthodontic tooth movement may be indicated to improve proportions.

Occlusal factors – in addition to requiring mesiodistal space, the pontic requires adequate vertical space (Figs 1-5 and 1-6). The pontic will have to compensate for any discrepancy in the opposing occlusal plane. It may result in a poor maximum intercusping relationship or compromised aesthetics. Furthermore, an overerupted tooth increases the risk of deflective contacts in lateral and protrusive movements. These deflective contacts generate horizontal shear stresses that are poorly tolerated by luting agents.

Fig 1-5 Inadequate mesio-distal width for a pontic site. (a) Insufficient mesio-distal space exists for prosthetic replacement of congenitally missing maxillary lateral incisors. (b) Creation of sufficient space is best achieved through orthodontic treatment.

Fig 1-6 Inadequate vertical space for a pontic site. (a-b) As a result of over-eruption of teeth 23 and 24 the pontic on the FPD from 35 to 33 has to compensate for the discrepancy in the occlusal plane (red line). (c) This results in an unaesthetic pontic and increases the risk of occlusal interferences.

Aesthetic Considerations

Aesthetics are examined both in the face and smile. Individual observations in each area should be noted to complete a problem list. When assessing aesthetic appearance in the face, the following questions should be addressed:

When assessing aesthetic appearance in the teeth and smile of the patient, the following questions need addressing:

What is the patient’s perception?

Is the patient happy with his or her dental appearance?

Are the patient’s expectations achievable?

Is a multidisciplinary approach required?

Is the maxillary midline correct relative to the centre line of the face or centre of the philtrum of the upper lip? Significant deviations may not be correctable by dental restorations alone.

What teeth are visible in repose and full smile (Fig 1-7)? Is this appropriate for the age of the patient? (In repose a young female should show 3–4 mm and a male 1–2 mm of the maxillary anterior teeth).

How far distally can be seen in repose and full smile, and is it symmetrical?

There are four aesthetic indicators notable in relation to the dentition:

Colour – note teeth both individually and collectively.

Dimension