Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Serie: Folk Tales

- Sprache: Englisch

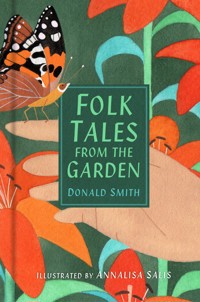

The garden is an oasis, a pocket of nature in our busy modern lives, full of plants, animals, insects – and a fair bit of magic. Folk Tales from the Garden follows the seasons through a year of stories, garden lore and legends. Explore the changing face of nature just outside your front door, from the tale of the Creator painting her birds and the merits of kissing an old toad, to pixies sleeping in the tulips, and an unusually large turnip.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 269

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2021

The History Press

97 St George’s Place,

Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire,

GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Donald Smith, 2021

Illustrated by Annalisa Salis

The right of Donald Smith to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9775 1

Typesetting and origination by Typo•glyphix, Burton-on-Trent

Printed and bound in Turkey by Imak

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

For William, Esther and Roberta Houston, and Willie O’Hara: my Irish storytellers

Contents

Introduction:

A Calendar of Stories

January

Twelve Months

Bringing in the Year

Ranting Roving Robin

February

First and Last

Town Mouse and Country Mouse

Rat and Weasel

March

Clever Crow, Wily Fox

Tim Vole

Fussy Wren

April

Cherry Blossom

Paradise Regained

The Tulip Pixies

May

The Marriage of Bride

Poppy May or Thumbelina

Five Queens

June

Say it with Flowers

A Midsummer Dream?

Not Kissing the Frog

July

Jack and the Magic Beans

Fruit of Love

Beauty and the Rose

August

Mr McGregor’s Garden

A Bride for Mole

The Butterfly that Stamped

September

Grian and Auld Goggie

Bird or Beast?

King of the East, King of the West

October

Apple Girl

Home or Away

Halloween Walking

November

Traveller Soup

The Enormous Turnip

Evergreen

December

Donald and Mary

The Green Knight

Robin Redbreast and Jenny Wren

Introduction

A Calendar of Stories

Most of us encounter plants, birds, animals and insects in gardens or parks. Folk Tales from the Garden celebrates this relationship through the changing seasons, with stories that have been created over generations.

During any given year, or even month, we can experience an astonishing variety of weather in Britain and Ireland, along with a constantly shifting balance between daylight and dark. These changes generate dynamic patterns of growth, decay and renewal. Life is always on the move, sometimes visibly and sometimes hidden from view.

These cycles are, of course, ‘out there’ in the natural world, but we also experience them in daily emotions and perceptions. That is hardly surprising since human beings are part of nature, yet we often appear unaware of our intimate connection. Robert Burns, Scotland’s national poet, described his connection with a field mouse whose home his plough had upturned as belonging to ‘Nature’s social union’.

My own garden sits on sloping ground below Arthur’s Seat, which is a royal park in Edinburgh. The landscape and climate of central Scotland are similar to that of our southern uplands, northern England, the Midlands, much of Ireland and the Welsh Marches. By contrast, the Scottish Highlands and southern England have significantly different seasonal timings and natural habitats.

North of my small walled garden is a patchwork of enclosed gardens dating from medieval times to the eighteenth century, when Scots embraced the ideal of rus in urbe, or ‘countryside in the town’, as embodied in gardens. In my more immediate area, there is a mix of suburban gardens, including nineteenth-century villas and twentieth-century bungalows.

To the south and east lie what were once enclosed estates. Their woods and parklands still survive in places, alongside built-up areas of modern housing, industrial estates and sports grounds. The land is criss-crossed by streams, or burns, stretching towards Duddingston Loch and the Forth shore, though these are blocked due south by Craigmillar with its wooded hill and castle. The south-facing chateau-style formal garden there brought much needed consolation to Mary Queen of Scots. In earlier times, all the surrounding territory was a royal hunting ground for Scotland’s medieval kings.

In different ways these gardens are a bridge between humans and nature. Each day, if I keep my senses alert, there is something different happening in my garden and across this wider environment. In addition to the seasonal changes, there are many people encouraging and sustaining natural diversity in the face of climate change. Alongside the private enclosed gardens there are community gardens, allotments and actively managed public green space.

Many storytellers, gardeners, poets and naturalists have inspired these pages – too many to name. But among the naturalists, I must mention David Stephen and Michael Chinery, whose books were prized childhood possessions, and the prolific all-rounders, Richard Mabey and Mark Cocker. The storytellers to whom I owe especial gratitude include tradition bearers Duncan Williamson and Ruth Tonge; fellow storyteller and gardener Grian Cutanda; literary masters Hans Christian Andersen, Rudyard Kipling and Beatrix Potter; anthologists Joseph Jacobs, Norah Montgomerie, Jean Marsh, Vigen Gurion, who introduced me to the Armenian Apocrypha, and Italo Calvino, who so meticulously and modestly points the way to those who heard and transcribed the peasant storytellers of Italy. It has also been a special pleasure to collaborate again with Sardinian illustrator Annalisa Salis, who has over the years become one of Scottish storytelling’s best friends.

My hope, of course, is that this book will encourage your own observations, memories, imaginings and creative interventions. Perhaps it is through our gardens – past, present and future – that we can make our peace with nature and repair the planet we have so foolishly tried to conquer and destroy.

JANUARY

January comes in dark, cloudy and damp. This began before Christmas, after a cold snap, fulfilling the gloomy prognostication – ‘Green Yule makes a full kirkyard’. Flues abound and in far-off China a new virus gestates.

We are past the year’s shortest day, but there is little sign, as yet, of any change in our northern latitudes, morning or evening. Oddly, short days mitigate against growth, yet all the other conditions are present. The vegetable bed still harbours turnips, winter cabbage, leeks and kale. Scottish winter gardens were once called ‘kailyards’, which came to signify all things homely, practical and parochial. The kailyard supplied soups and helped give flavour to slightly mouldy stored potatoes. But there is little impetus for warming broths when the temperature ranges between 6 and 12 degrees centigrade.

Some almond blossom shows prematurely, along with a few branches of flowering currant. Snowdrops appear in some locations and the crocuses are pushing through. The garden birds are active, though perhaps puzzled. Blue tits, sparrows, chaffinch, bullfinch, robin and wren can feed freely without depending on human supplies. There is fresh water aplenty. Each evening gossipy jackdaws gather over the higher roofs, ready at some mutually determined moment to fly to roost in the crags of Arthur’s Seat. Has that departure time shifted a little later? A first clue perhaps to the barely discernible lengthening of light, still overshadowed by cloud.

The digging impulse has petered out, but I do tackle the nettles that cluster in an old turf bank at the foot of the vegetable beds. Presumably at some point the beds were extended; the turf was cut and stacked at one end. The nettles love this rough bank and have rooted in deep. However often I dig them out, they come back. Of course, the old kailyarders would have welcomed these sturdy native nettles for soup and curative infusions.

I feel the lack of frost like an ache or absence. I imagine weeds waking far too early in earth that should be asleep and dreaming. The compost bins are overflowing, neither freezing nor fermenting, to the naked eye at least. The worms look pallid and sluggish. I treat them tentatively to a small keg of beer that was opened but not finished at Hogmanay. They definitely liven up and catch the party spirit despite dreich days.

It is time to take advantage of this unexpected and slightly dreary lull. A long-postponed clearance of badly overgrown ivy down the garden boundary becomes possible. We have new neighbours with a baby, and they will want to start afresh with their garden, unencumbered by my accumulated ivy thickets, entangled as they are with some neglected shrubs.

There are at least three kinds of ivy in this unpremeditated and uncontrolled hedge. One variety is flowering, and its leaves have become less variegated and more pungent. It is a heavy, hidden scent, dark and mouldering, though not poisonous. The plant’s latent energy seems to contain all the recessive strength of these unseasonable conditions when everything is on pause.

The plants range from thick-trunked bearers to trailing outriders, which then take root in their own right. Also in the mix are old briars, and Russian vines unwisely added at some haphazard juncture to ornament the boundary. All of this must go, to be replaced in early summer by climbing roses and small apple trees. That will provide colour and foliage of some kind all year round. I begin, armed with saw, shears and secateurs. But is this a long campaign rather than a single battle? Have I underestimated the scale of the task?

January begins traditionally with important rituals, such as Twelfth Night and Wassailing the apple trees while nourishing their roots with cider! As the month proceeds, Scotland prepares for Robert Burns Day on the 25th. In recent times, that natal feast of our national poet has become a week-long festival. Of course, we need winter festivals in the north from our New Year Hogmanay onwards. Burns becomes an excuse for recitations, dramas, toasts, music, song and haggis.

Haggis is a mix of oatmeal and offal cooked in a sheep’s gut. In harder times it was an ideal way to use every part of older animals that had been killed for our winter survival. Even the sheep’s head was used to add flavour to a winter vegetable soup – ‘sheep’s heid’ broth. Haggis should be served with ‘chappit [mashed] tatties’ – potatoes from the winter store – and turnips – ‘neips’ – also mashed. These delicacies are neither light nor especially delicate, but they do evoke a hardy spirit of survival in which farm and garden play their complementary parts.

At one time, turnips and kale were vital staple foods, essential to humans and animals for winter survival. Now people can eat them with sentimental relish, or culinary incredulity. Robert Burns reminds us of the need to hang together even through warmer days, because harder times may return to challenge our solidarity and good fellowship.

Twelve Months

Once upon a time, not in your time or my time, but it was once upon a time – there was a king who had two daughters. There were five years between the girls. Now, the first princess, Annie, was as cheery and as lovely as the day was long. She was always kind and considerate to everyone she met. But her younger sister, Jezebella, the second princess, was grumpy, spoilt and lazy. She was always whingeing and moaning as if everyone and everything was conspiring to make her life a misery. She stayed in bed most of the day watching Netflix and sending nasty tweets to her so-called friends.

Now the queen was very jealous of the king’s affection for her older daughter. She watched for every chance to slight Annie and make her look bad beside her younger sister, Jezebella. But it was almost impossible to do this, because the king was very loving to both girls, and besides, Annie was so nice that nastiness washed off her like water off a duck’s back.

Then one time, a week before Christmas, there was hunger in a distant part of the king’s lands. The weather had been terrible with deep frosts and blizzards of snow. The king, being a good king, set off immediately to help his people, leaving the queen in charge at home.

She did not act immediately but circled like a watchful snake homing in on her prey. ‘Dear daughter,’ she said to Annie, ‘you know that the king is away from home. But I am sure that when he returns, he would like to taste some fresh blackberries.’

‘That would be nice, mother, for sure,’ Annie replied, ‘but blackberries are out of season, especially in this cold weather. The garden is frozen over, even the walled fruit garden.’

‘Nonsense, girl, have you no consideration for your own father? Sometimes I think you have no feelings for him at all, unlike your dear sister who is so affectionate towards her parents. Of course there are blackberries out in the forest. Here is a basket for you to fill with fresh fruit. Bring it home so that your father can enjoy the berries when he returns.’

The princess did not wholly recognise her sister in the queen’s description, but she did not protest or complain. Instead, she wrapped up warmly and headed into the forest with the empty basket on her arm.

‘That’s the last we’ll see of her,’ thought the queen, gloating at the newfound power she had over the elder daughter now that her father was far from home.

But as Annie walked through the forest, the snow seemed to get deeper and deeper. You could hardly see the undergrowth where blackberries might grow, as it was all buried below mounds of white snow. Also, a fierce north wind was blowing through the bare branches, driving the falling flakes into her face. Darkness descended on the forest. The girl trudged on, but she was tiring and was about to give up and turn back when she saw what seemed like a glimmer of light ahead. ‘Perhaps,’ she thought, ‘there is a woodcutter’s cottage in this part of the forest.’ Annie’s step quickened and her courage rose.

As she drew towards the light it became stronger, and suddenly Annie was looking into a clearing amidst the trees. At its centre was a roaring log fire and round the fire sat a circle of little people huddled in rugs and shawls against the cold. The girl stopped, astonished at the sight.

‘Come away in, lass, and welcome!’ said a little old man with a long straggly beard and red woolly bonnet. ‘Come and warm yourself up beside our fire.’

She went forward gladly. The wee men and women made room for her and soon she was sipping a hot fruity drink from a wooden beaker.

‘Well,’ said the little old man, who seemed to be some kind of king. ‘What is a girl like you doing out in the forest on a night like this?’ Twelve pairs of little twinkling eyes settled on Annie.

‘My mother, the queen, sent me out to look for blackberries for my father,’ she explained.

‘Well, well, your mother, you say. Very queenly she must be. It’s not the time for blackberries,’ replied the little king kindly.

‘I know. I can’t find any berries in the garden or the forest.’

‘Maybe we can help,’ said the king, looking round the circle. ‘October, would you be so kind?’ He gestured towards a little old lady with curly white hair and cheerful russet cheeks like an autumn apple.

‘Of course, my dear,’ she said and gestured for the basket.

Someone beside Annie took the basket from her hands and passed it round the circle towards October, who then passed it on round. By the time it came back the basket was full to overflowing with blackberries. Annie could not believe her eyes.

‘There, there,’ said the wee king, ‘are you warmer now? You’d best be off home as this night is not going to get any better.’

‘Thank you,’ gasped Annie. ‘I don’t know how to thank you.’

‘No need,’ said October, chuckling. ‘When you’re old like me, it just comes naturally.’

‘But who are you?’ hazarded Annie, turning back to the little old man in the red woolly bonnet.

‘I’m December,’ he chuckled in reply. ‘A kind of Christmas king. And we are all earth helpers.’

So off Annie went with a swift, sure step, feeling the wind behind her, while even the snow seemed less deep. In no time, she was back at the palace, and presented the blackberries to her mother.

‘Where did you get these?’ spluttered the queen, who could not believe her eyes.

‘In the forest,’ said Anna, for something at the back of her mind told her not to mention the twelve little helpers by the fire.

‘Well, you’d better get off to bed, and don’t disturb your sister, Jezebella. She’s been trying to get to sleep like a good girl while you’ve been roaming about at all hours.’

Annie said nothing but went gratefully off to bed and fell into a deep dreamless sleep. Unless everything that had happened to her that night was a dream …

Christmas passed with little merriment and no word of the absent king. The queen was consumed by jealousy and determined to be rid of Annie. Jezebella could not care less as she was experimenting with her new toys, Instagram and Snapchat.

At the very end of December, the queen instructed Annie to go into the forest and gather the first snowdrops. ‘Your sister Jezebella and I are so sad that the king has not come home. We must be cheered up with some fresh flowers.’

‘But snow is still falling,’ said Annie. ‘I’m not sure there are any snowdrops yet. Not a single one has peeked through, even in the garden.’

‘Of course there are snowdrops, out in the forest,’ insisted the queen. ‘Have you no feeling for your own mother? Here is a basket to fill with the flowers. And don’t think of coming back until you have it full.’

So, Annie wrapped up warmly once more and headed into the forest with the empty basket on her arm.

‘That’s the last we’ll see of her,’ thought the queen, gloating that this time the elder princess would not escape a well-deserved end.

As Annie walked through the forest, the snow seemed to get deeper and deeper. You could not see the ground where snowdrops might come through, as even beneath the trees everything was buried below mounds of white snow. Also, a fierce north wind was blowing through the bare branches, driving the falling flakes into her face. Darkness descended on the forest. The girl trudged on, but she was tiring and was about to give up and turn back when she saw that same glimmer of light ahead. Annie’s heart rose and her step quickened.

As she drew towards the light it became stronger, and suddenly Annie was looking into that clearing amidst the trees. At its centre was a roaring log fire and round the fire sat the circle of little people huddled in rugs and shawls. Annie was delighted by that friendly sight.

‘Come away in, lass, and welcome!’ said the little king, with his long straggly beard and red woolly bonnet. ‘Come and warm yourself up beside our fire.’

She went forward gladly. The wee men and women made room for her and soon she was sipping a hot fruity drink from a wooden beaker.

‘Well,’ said December, the Christmas king, ‘what are you doing out again in the forest on a day like this?’ Twelve pairs of little twinkling eyes settled on Annie.

‘My mother, the queen, sent me out to look for snowdrops to cheer her and my sister up,’ she explained.

‘Well, well, your mother, you say. Very queenly she must be. It’s not the time yet for snowdrops,’ replied the little king kindly.

‘I know. I can’t find any in the garden or the forest.’

‘Maybe we can help,’ said the king, looking round the circle. ‘January, would you be so good?’ He gestured towards an old man with a white face and long, tangled white beard. As Annie looked, she realised his beard was full of icicles.

‘Of course,’ January said and gestured for the basket.

Someone beside Annie took the basket from her hands and passed it round the circle towards January, who then passed it on round. By the time it came back the basket was full to overflowing with snowdrops. Annie could not believe her eyes.

‘There, there,’ said the wee king, ‘are you warmer now? You’d best be off home as this night is not going to improve on the day.’

‘Thank you,’ gasped Annie. ‘I don’t know how to thank you.’

‘No need,’ said January, in a low rasping voice. ‘When you’re frosty like me for centuries on end, winter flowers come naturally.’

‘Bye bye,’ chuckled the little king. ‘We do enjoy your visits but it might be better not to come again soon.’

So off Annie went with a swift, sure step, feeling the wind behind her, while even the snow seemed less deep. In no time, she was back at the palace and presented the snowdrops to her mother.

‘Where did you get these?’ screeched the queen, grinding her teeth in disbelief.

‘In the forest,’ said Annie, for something at the back of her mind again warned her not to mention the twelve little helpers by the fire.

‘Well, you’d better get off to bed, and don’t disturb you sister, Jezebella. She’s been trying to behave like a good, well-brought-up princess while you’ve been gadding about in the forest.’

Annie said nothing but went gratefully off to bed and fell into a deep dreamless sleep. Unless everything that had happened to her that day too had been a dream …

But the queen, her mother, could get neither rest nor sleep. She was consumed by hatred, and desperate to rid herself of Annie before the king, her father, returned. What could she send the wretched girl to do that would be truly impossible and ensure she never came back? She tossed and turned all night.

‘Dearest Annie,’ she hissed the next morning, ‘I have word that our beloved king will be back in the next few days. You have done so well bringing blackberries and snowdrops, but what your father really desires and needs, and will have, is fresh strawberries.’

‘Strawberries!’ repeated Annie in disbelief.

‘Yes, for I have heard that on the far side of the forest there is a rare crop of winter strawberries. Anyone who tastes that fruit will enjoy long life and freedom from pain. So, take this basket and bring it back full.’ And she wanted to add, ‘or don’t come back at all’ but she clenched her teeth to stop the words coming out and smiled thinly at Annie without opening her mouth.

So, Annie wrapped up warmly once more and headed into the forest with the empty basket on her arm. ‘That’s the last we’ll see of her,’ thought the queen. ‘Finally. Strawberries are impossible in January, the silly little besom.’

As Annie walked through the forest, the snow seemed to have settled in deep, frozen drifts. You could not see the ground where anything might grow, far less strawberries. Also, a fierce north wind was blowing through the bare branches, driving frozen flakes like shards of ice into her face. Darkness descended on the forest. The girl trudged on, but she was tiring and was about to give up and turn back when she saw that same glimmer of light ahead. Annie’s heart rose and her step quickened.

As she drew towards the light it became stronger, and suddenly Annie was looking into that clearing amidst the trees. At its centre was a roaring log fire and round the fire sat the circle of little people huddled in rugs and shawls. The girl was so relieved to see them.

‘Come away in, lass, and welcome!’ said the little king, with his long straggly beard and red woolly bonnet. ‘Come and warm yourself up beside our little fire.’

She went forward gladly. The wee men and women made room for her and soon she was sipping a hot fruity drink from a wooden beaker.

‘Well,’ said the Christmas king, ‘what are you doing out again in the forest on a day like this?’ Twelve pairs of little twinkling eyes settled on Annie.

‘My mother, the queen sent me out to look for strawberries for my father to eat when he comes home,’ she explained doubtfully.

‘Well, well, very queenly she must be, but a strange sort of mother. It’s not the time for strawberries,’ replied the little king.

‘I know. I can’t find any in the garden or the forest.’

‘Maybe we can help,’ said the king, looking round the circle. ‘July, would you be so kind?’ He gestured towards a little woman with golden hair and bright blue eyes winking out from her nutbrown face.

‘Of course,’ she said and gestured for the basket. Someone beside Annie took the basket from her hands and passed it round the circle towards July, who then passed it on round. By the time it came back the basket was full to overflowing with fragrant summer strawberries. Anna could not believe her eyes.

‘There, there,’ said the wee king, ‘are you warmer now? You’d best be off home as this night is not going to improve on the day.’

‘Thank you,’ gasped Anna. ‘I don’t know how to thank you.’

‘No need,’ said July, in a mellow singsong voice. ‘When you’re sunny like me, from the top of your head to the tips of your toes, strawberries grow out of your fingers.’

‘Bye bye,’ said the Christmas king. ‘We do enjoy your visits but I feel this might be your last for a while. Take care and good luck.’

So off Annie went with a swift, sure step, feeling the wind behind her, while even the snow seemed less deep. In no time, she was back at the palace, where she presented the full basket of strawberries to her mother.

The queen was speechless, incredulous and choking with fury. ‘Where did you get these?’ she gasped like a beached whale.

‘In the forest,’ said Annie, and this time she told her mother the truth, right out. ‘I met these little people around a fire in their clearing.’

‘Little people? In a clearing?’

‘Twelve of them.’

‘Right, that’s it. Jezebella! Get out of bed this instant. If these little elves can make strawberries in January, then they can make gold and jewels. This instant, you lazy, pampered little besom. We’re going to the forest to get their treasure. As for you, Annie, we’ve heard quite enough.’

‘But its freezing outside, and dark.’

‘You’d better get off to bed, and I’ll sort you out when we return. From now on, you can pay for your keep by working in the kitchen. There’s no time to lose. Quickly, Jezebella. If she can do it, so can you.’

The queen headed off into the forest, dragging her complaining daughter behind her. They stumbled in the darkness, but the queen drove on as if possessed. At last, she had got the better of her older daughter.

The snow had settled in deep frozen drifts. You could not see the ground and a fierce north wind was blowing through the bare branches, driving frozen flakes like shards of ice into their faces. At last, soaked through and half-dead from cold, they found the clearing. It was empty and silent. In the centre were dead ashes from a fire inside a circle of blackened stones.

‘Where are they? Come here now!’ yelled the queen.

Her voice echoed into the forest and then died. Her daughter clung to her in sudden fear. The queen looked round. Which way had they come? Which way should they go? As she staggered off into the forest the wind redoubled, and the snow began to drift and to blanket the forest floor. Once you lay down, unable to walk any further, the snow would cover you over for the rest of the winter.

When the king eventually returned home it was as a widower. He grieved for his foolish wife and daughter, but Annie looked after the palace and everyone in it with wisdom and kindness beyond her years. And in each season of the year, working in the garden and wandering in the forest, she thought of Earth’s twelve helpers, and the different gifts they brought every month. But she always had a special place in her heart for blackberries, snowdrops and ripe summer strawberries.

Bringing in the Year

Long ago, men and women, boys and girls, animals and birds, lived through winter, spring, summer, autumn and winter again, much as we do, despite some climate changes. But it was different because, apart from winter ice, there were no fridges or freezers. So, our ancestors, even within living memory, had to dry, smoke, pickle and store, so they could get through the lean months when very little grew.

At the start of a new year, they looked forward to the season changing and the sun’s return. This was a moment to celebrate and to share some of their precious stores of food. Life would once again prove bigger than any one person’s needs, wants or desires. It was time to rest and party, even if things had been tough.

When was this new year? It might begin with the midwinter solstice, with Yule that became Christmas, Twelfth Night, Hogmanay in Scotland, New Year’s Day, or even well into January with ‘Old New Year’, as people stubbornly hung on to the twelve days ‘taken from them’ by the Gregorian Calendar.

Whatever the celebration was called, it involved visiting and hospitality, with food and drink from the winter stores. There were customs and traditions surrounding such visits; these were named first-footing, wassailing, guising or mumming, in different places. There were rhymes and songs calling on people to open up their doors:

O man, rise up and be not sweir [reluctant]

Prepare against the Gude New Year,

My New Year gift thou has in store,

Gif me thy hart I ask no more.

Wassailers might sing:

A wassail, a wassail, throughout all the town,

Our cup it is white and our ale it is brown,

Our wassail is made of the good ale and true,

Some nutmeg and ginger, the best we could brew.

In all cases, the visitors would insist that they were not beggars but ‘neighbours you have seen before’. Some would go on to sing in return for their supper, while others presented a mummers’ play with a hero, a villain, conflict, death and resurrection. Contributions of food and drink still applied though as the last act:

Blessed be the master o’ tis house, and the mistress too

And all the little bairnies that round the table grew.

Their pockets full of money, the bottles full of beer –

A Merry Christmas, Guisers, and a Happy New Year!

For gardeners, wassailing brought an extra benefit, when the guisers proceeded into the orchard and toasted the trees, often with cider in a wassailing bowl or bucket!

Old Apple Tree we wassail thee and hope that thou will bear,

For Lord doth know where we will be till apples come another year;

To bloom well and to bear well, so merry let us be,

Let every man take off his hat and shout out to thee, old Apple Tree.

Old Apple Tree, we wassail thee, and hope that thou will bear,

Hat fulls, cap fulls, three bucket bag fulls,

And a little heap under the stair.

Who could ask for more? Or for a more auspicious start to another growing season? With the upsurge of community gardens and orchards, these customs have found a fresh lease of life.

Ranting Roving Robin

It was late January in Scotland, when a wild storm blew in from the Atlantic Ocean onto the Ayrshire coast. With the storm came gale-force winds, hail, sleet and snow, blasting the towns and little villages across the south-west.

Among the victims was a recently built cottage in Alloway, which was surrounded by a market garden. The young gardener, William Burns, had worked hard with his own hands to build the cottage, as well as establish his gardening business on the outskirts of the prosperous county town of Ayr. His heavily pregnant wife Agnes was about to give birth to their first child.

As the storm’s fury mounted, the labour began, and William had to set out to fetch a midwife. But the River Doon was in full flood. He had to wade across and the carry the stranded midwife over on his back through the raging waters. William was a determined man and his son Robert, who was born that night, was always to admire and respect his father, even when pursuing a completely different path through life.