8,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

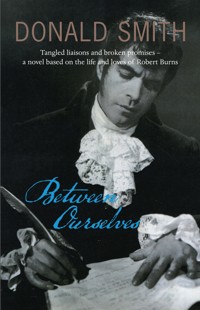

This tale of intrigue and betrayal goes to the heart of events surrounding the Treaty of Union in 1707. Daniel Foe (better known as Defoe), sent to Scotland to sway opinion towards Union, reports to his English spymaster. But Edinburgh is already a hotbed of counter-plots and nascent rebellion. Foe's encounters with a landlady who is not what she seems, and with a beautiful Jacobite agent, lead him to become a novelist, against his better instincts.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

A Warning to the Reader

IN 1706 SCOTLAND shared a Queen with England, Ireland and Wales, but still had its own sovereign parliament in Edinburgh. It was sixteen years since James vii and ii had been overthrown in a revolution, and within the next ten years there would be three attempts at armed revolt in Scotland culminating in the nearly successful Jacobite Rising of 1715.

In that same year of 1706 a journalist, recently imprisoned pamphleteer and failed merchant, Daniel Defoe, came to Scotland under secret instructions from the English Government. His mission was to persuade the Scots to give up their independence, and he was required to provide London with clandestine reports on affairs in the north.

Although most English people had no wish to unite with Scotland, it was felt vital to ensure the succession of one Protestant ruler for the united kingdoms of Britain and Ireland, Queen Anne being childless and ailing. The Scottish Government led by the Marquis of Queensberry favoured union with England, but there was clamorous patriotic opposition fronted by the Duke of Hamilton.

All of this took place many years before Defoe became famous as the author of Robinson Crusoe and Moll Flanders. In Scotland he was playing a bewildering number of roles, while still adhering to his Puritan faith and claiming the high ground of political principle. Having worked undercover, he even had the cheek to publish an ‘official’ history of the Union.

Who was Daniel Defoe? In the end he himself turned to autobiographical fictions to try and find out. The seeds of that late harvest, though, were sown in Edinburgh – making the English novel an early fruit of Union?

Yet why did Scotland surrender its hard won and long cherished independence? The historians remain divided. What is offered here is fiction, yet as Defoe himself shows the truths or apparent deceits of fiction may be uncomfortably closer to home.

Reader, you have been warned.

CONTENTS

A Warning to the Reader

Part One

Part Two

Part Three

PART ONE

GOD MADE ME a scribbler for his own inscrutable purpose. He plucked me from the debtors’ jail and placed me in his debt. My writing had not gone unnoticed or unpunished – it put me in the stocks. But now my talents were to be applied to my master’s purpose – his political purpose.

I had no other option than to obey. Yet this chimed with my own conviction. To go to Scotland and secure the unity of a new Protestant nation was a spur to my settled inclination, and also a confirmation of my vocation. But that only became clear much later. How long already I had languished awaiting such direction. I travelled north incognito yet brimming with hope and righteous energy. I was innocent of what lay ahead.

Now my book is published, my safe haven is reached. The History of the Union between England and Scotland by Daniel Defoe. I added the ‘de’ in deference to my French forebears. Would that I could dedicate that volume to my patron and protector Robert Harley, but our connection must remain undisclosed.

For the first time you have had an account of these proceedings – the great affair of North Britain. Yet I freely own the whole has not been revealed. My true part lies still in obscurity. The secret history of how Great Britain was made.

Good Mrs Rankin has written from Edinburgh to commend my poor efforts. Propriety, the most important thing, she avers, has been observed. A respectable widow has been allowed to live in peace and pursue her business. I can hear the firm Scots tones of my dear friend. But at times we were storm-tossed and close to shipwreck. That chapter is closed, to our mutual gain in the end, yours and mine.

Yet Isobel may have given me the opening I desire. What, after all, are our own lives, except a kind of story?

When she gave me her confidence I was moved, for her and for the orphan she had taken to her breast. I felt strangely possessed by their experience even though they were of the gentler sex. My sympathies were aroused and so I believe would be those of any manly reader. That is why I have written this private memoir, as if it were a fiction. You alone must judge who is the author and who a mere actor.

I fear it is like playing God.

You cannot understand this story without picturing the town of Edinburgh. Nowhere in Europe, including London, has built higher. The tenements are piled up six or seven stories on each side of the High Street, but clambering also in subterranean layers down through the rocky steeps of the town, north and south.

Descending from the rugged looming fortress on the Castle Rock you follow the stony backbone of the Royal Mile. Halfway to Holyrood Palace, you reach the Netherbow, principal Port or Gate of the old city. Beyond, they say, lies the world’s end, wolves and the English. In truth beyond the gate the mansions of Scotland’s powerful line the Canongate, forming a ceremonial way to the seat of royal power. Until, that is, Scotland’s kings moved to Whitehall and to Greenwich.

Around the Netherbow are bunched ancient medieval lands or tenements. With their twisting turnpikes, forestairs from the street, jutting timbered galleries, shuttered windows and carved stone facades, these buildings were once the lairs of merchants, courtiers and kings. But now they have been layered into urban lodgings, sedimented strata for the often less than great who pack this crag-constricted Scottish burgh. Edinburgh clutches status to itself like a tattered standard.

Mr Foe’s lodgings were adjacent to the Port, three storeys up. The narrow turnpike stair was dim and reeking of the ordure in the open causeway. But the room was warm, wood-panelled and open to the street, a snug cabin with easy access to the bridge.

‘I hope the room is suitable.’

‘It is ideal, Mrs Rankin.’

‘As soon as you are ready, come down and take a refreshment.’

‘Thank you. I shall.’

Half an hour later, having left his bags securely strapped Foe descended carefully to his landlady’s hospitable parlour. Kists, rugs, carved settles, painted beams and a faded though elaborate tapestry populated a room more spacious than his own private chamber. A cheerful coal fire burned in the hearth, drawing the room into itself away from the dirt and noise beyond.

‘A glass of claret, Mr Foe?’

‘I will, though I am more used to a jug of ale.’

‘What you Englishmen call ale is not what we describe as beer.’

‘Indeed not. Your ale, Mrs Rankin, is really small beer. A different brew altogether. You might drink a pint or two with equanimity.’

‘The Scots, Mr Foe, drink a pint or two of anything with equanimity.’

‘Surely sobriety is the rule in Edinburgh. Dissipation is a London fashion. I know that I will find much to admire in the capital of Presbyterianism.’

Sitting on opposite sides of the generous fire, the English visitor and his Scottish host sipped their claret from long-stemmed glasses that glinted in the flickering light of the flames. Foe was small in stature with a stomach spread by early middle age. Beneath an orderly, curling wig his features were precise and neat. A tailored coat and waistcoat bespoke careful preparation, with a dash of fussy self-importance.

‘Your business may bring you into closer acquaintance with our ways,’ observed Mrs Rankin. ‘I believe you have never been in Scotland before.’

Foe looked with interest at the small, well-formed figure on the other side of the fire. A plain yet handsome dress could not conceal the rounded fullness beneath.

‘My business here is private. Affairs of trade are uneasy due to the Union question and I am pledged to promote good relations.’

‘I keep a quiet house, Mr Foe, which is why my guests find this such a convenient lodging.’

‘Guests?’

‘Lady O’Kelly arrived today from Ireland. She went immediately to her room to rest.’ Foe tugged at his waistcoat. ‘She has had a long journey but I sent the lassie to ask her down,’ Mrs Rankin continued. ‘A refreshing glass will soon restore her colour. This will be her now.’

Dear Nellie,

You can see it just as I talk. As Mr Foe rose, quite the gentleman, in walked Catherine. Yes, Lady O’Kelly is our Catherine got up like a lady of fashion. Those clothes came dear and, being in trade, I could see Foe was impressed. She never blinked, bold as brass. My mouth must have been hanging open. It was like a stage play, not that we have ever seen one in Edinburgh.

‘May I present Lady O’Kelly of Balnacross. Mr Foe a merchant of London.’

Somehow I got that out and they sat down. Then she, Catherine I mean, interrogated the poor man. His business. His politics. His religion. Foe took it very smooth, almost too smooth I thought, Nellie, and you have a nose for those things. A dissenter, he said, without political conviction; he was here on private business.

Then he asked Lady O’Kelly, our Catherine, why she was in Edinburgh. That brought out the actress along with the hankie. Her husband had died three months ago (you remember Robert, Nellie, who was never a knight that I recall though he pretended to landed connection in Ireland). His only surviving relation had since passed away in Edinburgh and she was now here to settle the estate. Another snuffle.

Mr Foe was solicitous. I offered more refreshment and she downed two drams. Finally he made off to his room. Perhaps he did not like a woman to drink.

‘What are you doing here?’ I started, ‘Is Robert dead?’ I couldn’t hold back, Nellie, as you may credit. ‘You left with a name, an estate, a husband. Why risk that now, with a false play acting?’

‘I worked hard for these gains,’ says she. What a coarse way of speaking! I scolded and then she threw it back in my face. These were her words – and I want you to hear them yourself: ‘For all the management you had of me and of women like me, you still cling to society.’ I am sure I have it exact. ‘Don’t pretend to rank and then you will rise. Men of breeding wish to bestow, not to yield. Bedchamber intrigue is the true path to power.’

She always had a sharp tongue, that one. But it is true for all that, and I told her so despite her cleverness. I can’t repeat what she said next but it had bailies unbuttoned in High Street closes. Her Irish accent slipped then, Nellie, I can tell you. Our own Scots tongue can be very unbecoming.

At the end it came out. Robert is penniless and in trouble. You know what I mean – kings over the water trouble. Ever a gambler. Now Catherine is trying to recover their situation by getting into even deeper waters.

She asked me right out if I still had a connection with a certain nobleman. Could I arrange for her to meet with him? Then she offered me any favour I liked in return. Would you credit it? Who does she think I am?

But, Nellie, the worst is I felt afraid for her. Like some mother sheep that sees her lamb heading for a raging torrent. The years melted away – if I wasn’t telling you now I wouldn’t have believed it of myself

When I know any more I will write. Don’t mention it to any of our acquaintance. How many people here will remember her? She must remain discreet entirely.

Your own,

Isobel

Pens paper and ink on the table. Shirts in the – what did she call it – press. Brushes and razor on the shelf. Books, notes and letters – one so far – in the iron-hasped chest padlocked under the bed. Key in pocket.

Foe looked round his room and gave a quick nod of satisfaction. All was snug and trig, protected from the darkness. He could hear a wind picking up outside; perhaps it was raining. Magdalen Chapel was in the Cowgate, somewhere to the south below the High Street.

Treading carefully down the uneven turnpike He realised that it would be almost impossible to pass Mrs Rankin’s first floor rooms without being observed. And sure enough, ‘Mind the dark stairs, Mr Foe,’ she called, ‘I always leave this door ajar to cast some light.’

‘Thank you. Good evening.’

The heavy door swung onto the outside stair head and abruptly Foe commanded a sweeping view of the street. He stood for a second, like a surprised general reviewing his unruly parade. Wagons piled with market wares queuing to manoeuvre through the narrow Port. Horsemen weaving through the melee. Pedestrians, their faces lit by torches, muffled against the noise, the stench and the cold. On each side of the causeway a mass of shadows seemed to pushing towards the light and then ebbing back.

Foe launched into the throng, gathering his cloak protectively across his features. At the Tron Kirk he noticed an idler dangling a torch.

‘Are you a cadie?’

‘Na, I’m the toun crier.’

‘Will you light me to the Cowgate?’

‘Aye.’

The ragged youngster plunged ahead of him down a steep alley, the pitch dark broken only by his bobbing torch. They issued into a narrower, noisier version of the High Street.

‘Whaur noo?’

‘Point me towards Magdalen Chapel.’

‘Its doon there. Will I tak ye?’

‘This is far enough. I’ll find my own way from here.’

Having paid his dues, Foe was outside the chapel within a minute. Amidst the crumbling morass, a lop-sided door led into a clutter of lesser buildings leaning on the chapel wall. He lifted the knocker and struck twice.

‘You are Daniel Foe?’

‘I am.’

Foe was led down a gloomy passage into a cramped chamber, where two black-suited men sat before a meagre fire. One stood up.

‘You hae letters o introduction?’

These were roughly opened and scanned.

‘Please be seated, Mr Foe.’ This from the younger, smoother clergyman on the right. ‘You understand that our willingness to meet you implies no sympathy for the interests you may represent.’ He was tall and stiff, even when seated.

‘Be easy, gentlemen. My friends wish simply to hear your views, and to represent the warm esteem in which they hold the Kirk of Scotland.’

‘Are you committed to Christ’s true Kirk, Mr Foe?’

‘I have suffered for that cause.’

‘Mister Foe wis pilloried – fur a poem.’ The burlier grey-haired minister relished the smear of poetry.

‘I wrote in praise of the dissenting clergy in England, though this was not wholly understood.’ Foe exhibited suffering self-righteousness.

‘In Scotland we ken whit sufferin as a true Christian signifies.’

‘Whom do you represent?’ The seated and apparently senior man waved Foe and his own companion onto wooden stools.

‘You have my letters of introduction.’

A look passed between the two ministers.

‘These are from reputable men of God who have little power in England and less in Scotland,’ observed the taller man.

‘Yet they desire nothing more than the union of our two Protestant nations.’

‘We’re no a persecuted remnant, Mr Foe. There is ane Kirk o Scotland and we require oor rights an privileges as the national church,’ rejoined the grey head.

‘The Treaty of Union would guarantee those rights.’

‘What is your authority for that assurance?’

‘The English Government,’ asserted Foe.

‘Weill, you surprise me.’

‘Furthermore there is one advantage that even Dissenters enjoy in England. The advantages of trade. England prospers and the future wealth of Scotland lies in a trading union with her closest neighbour. That could redeem at a stroke all the losses suffered from the Darien expedition.’

‘An whit o Scotlan’s honour? That’ll no be so easily pit richt.’

‘For whom do you speak, Mr Foe?’

‘I am not at liberty to be so direct.’

‘We kin see that fur oorsels.’

‘But my friends… your friends, are at the centre of affairs, close to policy,’ assuaged Foe.

‘If, and I say if, the Church of Scotland were to consider a Treaty, our General Assembly would insist on a separate Act guaranteeing our position.’

‘I can see no difficulty. It could be passed with the Treaty.’

‘Make sure your superiors are clear on that point.’ The negotiating position was driven home.

‘Wioot it we would raise the country agin you.’

‘But we are rational men, Mr Foe, of some standing in the Assembly.’

‘I do not believe that a separate Act has been considered but it is my place and privilege to advise on these matters. If it can be ma-naged in all our interests, my friends would not be ungrateful.’

‘The Kirk maun be guided, though we canna speak fur the Covenanters.’

‘Covenanters?’

They had not entered Foe’s calculations.

‘Aye, no all the brethren are sae docile.’

‘The continuing Covenanters, or Cameronians as we say, remain unsatisfied with King William’s settlement in 1690.’

‘The Covenant wisna mentioned.’

‘They remain ready to take up arms, where they are strong in the southwest.’

‘Can I meet with the Covenanters?’ Foe cut in on their exchange.

‘The rule o law barely raxes that faur. We dinna deal wi outlaws.’

‘Of course. I shall look into it further,’ conceded Foe.

‘But we micht drap a hint in the richt lug.’

‘You have been of great assistance. Messages can be left for me at the White Horse Inn under the name of Deans.’

The younger minister rose in pious exhortation. ‘We must seek the Lord’s will for his people in these troubled times.’

‘Our times are in His hand. I will leave ahead to avoid suspicion,’ responded Foe. He turned back up the gloomy passage and out into the night.

‘He’s awa. Whit do you think?’

‘He’s smooth-tongued onyroads, but he micht be useful. Very useful.’

The Journal of Lord Glamis. There –I have committed those words to paper.

It is three days since I denied entry to Father Aeneas. Twice he came back. I had him turned away at the door. From my upstairs chamber I watched him drag his steps up the Canongate.

That beautiful head hung down.

Already I feel his loss. What do I miss most? The lean strong body. The raven black hair. The lowered eyes when he heard my confession. Was it not a sin that the gifts of nature should be so prodigal in a man denied fruits of the flesh?

I should burn this journal daily at the altar. Or after each week. Yet these words demand to be written; they cannot any longer be spoken.

This is what I must not tell anyone except myself. It will not please any reader. God does not spy. He already knows my intent.

When I gave the instruction to refuse Aeneas my door, I knew that the change had begun. This was the commencement.

On the outside I shall remain constant. Speaking. Commanding. Voting. Whoring. But anchors on which I rested are twisting on the sea bed. Shifting. I look for the image of my mother as she was in life but find nothing. Uprooted.

It is not my doing. Darien did this to me. It started where I pledged and lost so much in the swamps of Panama. That was to have been my fortune and Scotland’s empire. All gone like the last glint of spirits in a glass. Debts are nothing new to my patrimony. My ancestors lived and died with debt. Yet there was always a King to favour and reward.

Three days I have not prayed. Why confess. I have not held his sacred body between tongue and lips. Too dangerous.

An emissary is expected. The papers must come to me and not pass through another’s hands. I kept him as a private secretary.

What will Father Aeneas do? He has so many talents he will not starve, but if he does not return to Europe he could be exposed and hung. No track should lead back to me. I must not acknowledge him in the causeway. Those doleful eyes.

I shall play my part to the close. There has been nothing like this before, since everything is to be lost or gained. Can faith provide for that?