Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

The trail follows the emergence of democratic thought and action in Scotland from the 16th century onwards, linking pivotal events to locations along the way. It is a story of ups and downs, triumphs and tragedies, borne along by a stubborn, persistent advance. The evolution of democracy in Scotland is a fascinating story. Join Stuart McHardy and Donald Smith as they tell this story via a guided tour of the landmarks and monuments of Edinburgh, leading you from Edinburgh Castle to the Scottish Parliament, and through over 500 years of political development. From the antics of the Edinburgh Mob and the cruelties of Henry Dundas, to the more recent Vigil for a Scottish Parliament and the 2014 referendum on Scottish independence, this book will show you the democratic and historic significance of the places, people and ideas on the route. A comprehensive timeline, detailed map and photographs throughout make it easy to follow the route and discover the story of Scottish democracy. Scotland's Democracy Trail brings the key political events in Scotland's history to life, demonstrating just how relevant they remain today.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 116

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

STUART MCHARDY is a writer, occasional broadcaster and storyteller. Having been actively involved in many aspects of Scottish culture throughout his adult life – music, poetry, language, history, folklore – he has been resident in Edinburgh for over a quarter of a century. Although he has held some illustrious positions, including Director of the Scots Language Resource Centre in Perth and President of the Pictish Arts Society, McHardy is probably proudest of having been a member of the Vigil for a Scottish Parliament. Often to be found in the bookshops, libraries and tea-rooms of Edinburgh, he lives near the city centre with the lovely (and ever-tolerant) Sandra with whom he has one son, Roderick.

DONALD SMITH is the Director of Scottish International Storytelling Festival at Edinburgh’s Netherbow and a founder of the National Theatre of Scotland. For many years he was responsible for the programme of the Netherbow Theatre, producing, directing, adapting and writing professional theatre and community dramas, as well as a stream of literature and storytelling events. He has published both poetry and prose, and is a founding member of Edinburgh’s Guid Crack Club. He also arranges story walks around Arthur’s Seat.

Other books by Stuart McHardy:

Scots Poems to be Read Aloud: Yin or Twa Delighfu Evenin’s Entertainment (Luath Press, 2001)

The Quest for Arthur (Luath Press, 2001)

The Quest for the Nine Maidens (Luath Press, 2002)

School of the Moon: The Highland Cattle-Raiding Tradition (Birlinn, 2004)

Tales of the Picts (Luath Press, 2005)

On the Trail of the Holy Grail (Luath Press, 2006)

The White Cockade and Other Jacobite Tales (Birlinn, 2006)

Tales of Edinburgh Castle (Luath Press, 2007)

Edinburgh and Leith Pub Guide (Luath Press, 2008)

Tales of Loch Ness (Luath Press, 2009)

Tales of Whisky (Luath Press, 2010)

Speakin o Dundee (Luath Press, 2010)

A New History of the Picts (Luath Press, 2011)

Scotland the Brave Land: 10, 000 Years of Scotland in Story (Luath Press, 2012)

Tales of Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobites (Luath Press, 2012)

The Pagan Symbols of the Picts (Luath Press, 2012)

Scotland’s Future History (Luath Press, 2015)

Other books by Donald Smith:

John Knox House: Gateway to Edinburgh’s Old Town (John Donald Publishers, 1997)

Celtic Travellers: Scotland in the Age of the Saints (Mercat Press, 1997)

Memory Hill (Diehard, 2002)

Storytelling Scotland: A Nation in Narrative (Polygon, 2001)

A Long Stride Shortens the Road: Poems of Scotland (Luath Press, 2004)

Some to Thorns, Some to Thistles (Akros Publications, 2005)

The English Spy (Luath Press, 2007)

God, the Poet and the Devil: Robert Burns and Religion (Saint Andrew Press, 2008)

Between Ourselves (Luath Press, 2013)

Freedom and Faith: A Scottish Question (Saint Andrew Press, 2013)

The Ballad of the Five Marys (Luath Press, 2014)

Pilgrim Guide to Scotland (Saint Andrew Press, 2015)

Other books by Stuart McHardy and Donald Smith:

Arthur’s Seat: Journeys and Evocations (Luath Press, 2012)

Calton Hill: Journeys and Evocations (Luath Press, 2013)

Edinburgh Old Town: Journeys and Evocations, with John Fee (Luath Press, 2014)

First published 2015

ISBN: 978-1-910324-45-5

The authors’ right to be identified as author of this work under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

Map by Mike Fox

Photographs by Stuart McHardy unless otherwise stated

‘Freedom Come-All-Ye’ reproduced by kind permission of Kätzel Henderson

Typeset in 11 point Sabon by

3btype.com

© Stuart McHardy and Donald Smith

Dedicated to all those

who have struggled for Scotland

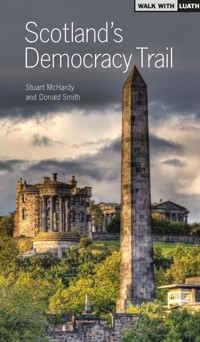

View of the beginning of the trail, taken from Arthur’s Seat

Courtesy of Ad Meskens, Wikimedia Commons

Contents

Map

Introduction by Stuart McHardy and Donald Smith

CHAPTER ONECastlehill

CHAPTER TWOGeneral Assembly Hall

CHAPTER THREEHigh Street, James Court

CHAPTER FOURParliament Square and John Knox’s Grave

CHAPTER FIVEThe Mercat Cross

CHAPTER SIXOld Assembly Close

CHAPTER SEVENNew Assembly Close

CHAPTER EIGHTThe Old Calton Burial Ground

CHAPTER NINERegent Road, The Governor’s House

CHAPTER TENCalton Hill, The Dugald Stewart Monument

CHAPTER ELEVENCalton Hill, The Vigil Cairn

CHAPTER TWELVERegent Road, The Vigil Plaque

CHAPTER THIRTEENRegent Road, The Royal High School

CHAPTER FOURTEENRegent Road, The Burns Monument

CHAPTER FIFTEENRegent Road, The Stones of Scotland

CHAPTER SIXTEENHolyrood

Timeline

Entrance to Edinburgh Castle

Courtesy of Chris Sherlock, Wikimedia Commons

Introduction

SCOTLAND’S DEMOCRACY TRAIL goes from Edinburgh Castle, down the High Street, across North Bridge to Calton Hill, and then on to the Scottish Parliament at Holyrood. Apart from its historic significance, the route encompasses Edinburgh’s most dramatic scenery and townscape.

The Trail follows the emergence of democratic thought and action in Scotland from the 16th century, linking pivotal events to locations on the way. It is a story of ups and downs, triumphs and tragedies, borne along by a stubborn, persistent advance.

The Trail moves back and forward in time showing the connections between influential ideas and key personalities in different periods. The roots of democracy run deep in Scotland – the leader of the Caledonians at the Battle of Mons Graupius in c. 8OCE was said by Tacitus to have talked of ‘Freedom’.

The pervasive influence of the 1320 Declaration of Arbroath must be acknowledged here, but our Trail concentrates on the footprint of democracy in our capital city. Attention is drawn to the roles of America and France in developing 18th century Scottish calls for parliamentary reform, but it is worth remembering that there were also Scots involved in the American Revolution, drawing on already established traditions of democratic thought.

As far back as the early 16th century, John Mair, a Scottish philosopher famed throughout Europe, postulated, among other things, that the people of a nation were more important than its kings, and that even non-Christian ‘savages’ had rights. Half a century later George Buchanan, after travelling extensively though Europe, became a Protestant and took the position of tutor to the young James VI. In his 1579 De Jure Regni apud Scotos (a dialogue concerning the due privilege of government in the kingdom of Scotland) he insisted that kings were not above the law. This was greatly influential in Scottish and British Protestant thinking.

To help make things clearer there is a timeline at the back of the book which gives a general historical background and then specific Scottish milestones.

The idea of Scotland’s Democracy Trail was suggested to the authors by the Minister for Culture and External Affairs, Fiona Hyslop MSP, on a visit to the Scottish Storytelling Centre with the Greek Ambassador to the United Kingdom in February 2014.

Stuart McHardy and Donald Smith

Edinburgh, June 2014

CHAPTER ONE

Castlehill

Map Location 1

STAND BESIDE THE narrow built-up passage that connects the town of Edinburgh to the fortress and Royal Palace of Edinburgh Castle. You can see today’s tourists crowding up into the approach. Historically this was a passageway of power. At the upper end, in Scotland’s premier stronghold and prison were sited royal sovereignty backed by military muscle, patronage through land and honours, a judicial right of life or death, and taxation, however inefficient. Below were the landowners with their townhouses and court offices, the merchants, the burgh citizens and the common people.

Looking down the Royal Mile

In medieval times and into the early modern period, hierarchy was the order of the day with the monarchy at the top of the pyramid. Only God ranked higher, though his earthly representatives in the Church struggled to influence ‘disobedient’ kings and queens who felt they had their own hotline to divine legitimacy. The monarchs would descend in procession down Castlehill to display their authority and wealth for all to behold and acknowledge. Sometimes their power was demonstrated by pageants, sometimes through imprisonments, executions and other ritual humiliations, all designed to overawe and entertain the mob.

Yet even in the medieval period the power of hierarchy was limited by obligations and duties that went up and down the scale. Rulers were bound into a contract with the ruled. Failure to play their part could lead to overthrow or worse. In practice most medieval monarchs struggled to exercise effective authority and desperately needed loyalty and practical support from those below to deliver on their appointed functions. In Scotland central government was perpetually short of cash and depended on financial contributions from churchmen, aristocrats (normally extracted under threat of confiscation) and the burgh merchants. Moreover, as Scotland had no standing army, defence against enemies within or without crucially required the willingness of the earls, knights and chiefs to muster in the cause.

One famous early incident illustrates this vividly. When struggling to retain their independence from England in the early 14th century, the Scots deposed King John Balliol, who had been selected by Edward I of England and came to be seen as his weak puppet, ‘Toom Tabard’ (meaning ‘empty coat’). Far from unanimously, the Scots crowned Robert Bruce in Balliol’s place, but his descendants refused to accept the legitimacy of this deposition, sustaining an intermittent civil war, with English support, for another 50 years.

In light of these events, the Community of the Realm of Scotland, composing of the Three Estates of Lords, Bishops and Burgh merchants, asserted in the 1320 Declaration of Arbroath that kingship in the realm of Scotland was conditional on the monarch performing his or her duties. Should Robert Bruce himself fail to deliver, the Declaration asserts, then he too would be replaced.

Unto him, as the man through whom salvation has been wrought in our people, we are bound both of right and by his service rendered, and are resolved in whatever fortune to cleave, for the preservation of our liberty. Were he to abandon the enterprise begun, choosing to subject us or our kingdom to the king of the English or to the English people, we would strive to thrust him out forthwith as our enemy and the subverter of right, his own and ours, and take for our king another who would suffice for our defence; for so long as an hundred remain alive we are minded never a whit to bow beneath the yoke of English dominion. It is not for glory, riches or honours that we fight: it is for liberty alone, the liberty which no good man relinquishes but with is life.

Royal succession might give you access to the throne but it did not guarantee keeping it. In England the earlier Magna Carta of 1215, which was imposed on a reluctant and unpopular King John, is a similar expression of ‘contractual kingship’. It was not until the 17th century that the idea of ‘absolute kingship’ developed in royalist opposition to more radical ideas about the rights of subjects or citizens. The medieval Stewart kings of Scotland swore a coronation oath that contained this pledge:

I shall be real and true to God and Haly Kirk and to the Thrie Estaitis of my realm. And ilk estait keep, defend, and govern in their ain freedom and privilege, at my guidlie power, after the laws and customs of the realm... and nothing to work na use touching the common profit of the realm without consent of the Thrie Estaitis.

One episode in this Castlehill location concerns the imprisonment in Edinburgh Castle of James III by his over-mighty aristocratic subjects. In fact Scots kings were frequently held hostage by lordly factions who could combine their armed followings to seize power by force. This happened especially when the ruler was a minor and each faction sought control over the Royal Court and its powers. In this instance however in 1482, the people of Edinburgh rose up to free the King from his captors. In response James granted the citizens a ‘Golden Charter’ enshrining their right to take up arms in defence of their freedoms and privileges.

The General Assembly Hall, as seen from the Mound

Courtesy of RepOnix, Wikimedia Commons

Tradition connects this lost ‘Charter’ with ‘The Blue Blanket’, a banner belonging to the Trades or Craft Guilds, which hung in the Chapel of St Eloi in St Giles’ Cathedral. This chapel, which survives in today’s cathedral without its earlier adornments, was maintained by the Guild of Hammermen or metalworkers, and their later offshoot, the Goldsmiths. Legend ascribes the original making of the Blue Blanket to the Crusades, but its likely origin is 1482. In 1513 it was carried at the Battle of Flodden from where it returned, despite the loss of Scottish life at that tragic defeat. Later the Blanket became a symbol of the Covenanters’ right to bear arms in their own religious and political crusade.

A 17th century version of the Blue Blanket survives in the care of the Convenery of the Trades of Edinburgh. In the 1980s a reproduction of this banner featured as the centrepiece of an Old Town community drama, and it was carried in the Edinburgh’s May Day procession once again in 2014. The inscription reads:

Fear God and honour the King with a long lyffe and prosperous reign and we that are Trades shall ever pray to be faithful for the defence of his sacred Majesty’s royal person till death.

In these earlier centuries Scottish kingship was not radically different from the European norms. But Scots rulers lived close to their subjects and could only reign effectively with a degree of popular consent and support. This was expressed through the Three Estates of the Lords, the Church and the burghs which were represented mainly by the merchants. It was also the fact that the kings of Scots spoke the same language, Scots, as the rest of the population.

In more remote regions, the earls and lords were effectively rulers in their own right. But people in the lowlands and burghs who saw the monarchs going about their business were loyal to Royal Government, on condition that it was exercised for the wellbeing, or commonweal, of the nation as a whole. Rulers were titled King or Queen of Scots rather than Scotland, emphasising the nature of this two-way relationship between monarch and people.