Forced sterilizations and patient murders – Mainkofen during the Nazi regime. E-Book

Heinz Michael Vilsmeier (EN)

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: epubli

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

During the Nazi regime, people were primarily evaluated based on their economic utility to the "national community." Individuals with mental illnesses, intellectual disabilities, or those labeled as "asocial" were classified by Nazi eugenicists as "hereditarily ill," forcibly sterilized, gassed in extermination centers, lethally injected in so-called healing and nursing homes, or starved to death. In an interview, the former commercial director of the Mainkofen District Hospital in Deggendorf, Lower Bavaria, answers questions about how the Nazi murder program was implemented in the clinic he managed.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 118

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Forced sterilizations and patient murders – Mainkofen during the Nazi regime.

Heinz Michael Vilsmeier

in conversation with

Gerhard Schneider

E-book

Imprint

HAMCHA art integration

Heinz Michael Vilsmeier

Spiegelbrunn 11

D-84130 Dingolfing

First English-language edition as e-book: 2024

© Copyright by Heinz Michael Vilsmeier 2014 und 2024

Druck: epubli – ein Service der neopubli GmbH, Berlin

Historical photographs, graphics, facsimiles and diagrams from the photo archive of Gerhard Schneider,with kind permission.

https://interview-online.blog

Gerhard Schneider was not honored.

We live in a time when anti-democratic, nationalist, and racist ideologies are once again on the rise. Much feels reminiscent of the ascendance of fascism between the two world wars. Right-wing extremists openly espouse fascist views in public spaces. Increasingly, they succeed in embedding nationalist, racist, and authoritarian concepts in the public discourse of democratically constituted states.

An example of this is the debate on asylum and migration policy. Central to it is the racist term "Great Replacement," used by the New Right to mobilize against the immigration of non-whites and especially Muslims. The narrative of the Great Replacement, in its modified form, relates to the ideas of ethnic purity once advocated by National Socialists.

Democratic politicians and opinion leaders must face the accusation of not forcefully opposing the demagogic narratives of the right about an imminent foreign infiltration, but instead even surpassing them with xenophobic legislation. The culmination of this policy so far has been reached with the EU's "Migration and Asylum Package," which includes further restrictions on asylum rights, the construction of walls, barbed wire fences, and surveillance facilities, the establishment and equipping of paramilitary border guard organizations, the brutal rejection of refugees and asylum seekers at the external borders, and the expansion of brutal deportations, expulsions, and internments in camp-like facilities. Fascists present these measures as confirmation of their ethnic slogans.

How can it be that nationalist and ethnocentric ideologies, which were the breeding ground for the humanitarian catastrophes of the 20th century in Europe, are becoming socially acceptable again? My thesis is that xenophobia is still deeply rooted culturally, even among democrats, and it spans all political camps.

Es ist das systematische Verdrängen, Vergessen, Leugnen und Entlassen faschistischer Täter und Täterinnen aus der Verantwortung – nicht nur in Deutschland. Sie konnten untertauchen, weil staatliche Institutionen sie schützten. Zumindest in Deutschland galt das nicht nur für diejenigen, die in der NS-Hierarchie oben standen, sondern auch für die emsigen Überzeugungstäter und -Täterinnen in den Behörden, der Polizei, der Justiz und der Öffentlichkeit, die keineswegs immer nur Mitläufer*innen oder Befehlsempfänger*innen waren. – Das Personal der Heil- und Pflegeanstalten bildete diesbezüglich keine Ausnahme.

The following conversation with the former hospital director of the District Clinic Mainkofen, Gerhard Schneider, who tracked down the traces of the perpetrators in doctor’s coats and the nurses and caregivers who forcibly sterilized and starved their patients, provides insight into a psychiatry that systematically implemented ethnic-nationalist patterns of thought in practice. It sacrificed the values of humanity to a calculus in which the cost and benefit of a person for the "national community" was the decisive criterion for their worth. Based on this, a distinction was made solely between worthy and unworthy life, and actions were taken accordingly. Estimates suggest that around 300,000 people fell victim to the delusions of ethnic eugenicists.

Figure 1.Festive hall of the Mainkofen Sanatorium and Nursing Home during Nazi ruleSource: Photo archive Gerhard Schneider

After 1945, the veil of forgetfulness was thrown over the horrors in psychiatry. The perpetrators, with few exceptions, remained in their positions. They continued to be responsible for patients, whom they would have forcibly sterilized or murdered before the fall of the so-called Third Reich – often for many years, and not infrequently until the end of the patients' lives in the institutions. Moreover, and this had even more lasting consequences, they were responsible for training new medical and nursing staff until the mid-1970s. Thus, psychiatry in Germany was for decades significantly influenced by a mindset that between 1933 and 1945 was the basis for forced sterilizations and patient murders.

The most unscrupulous "luminaries" were often publicly honored, streets were named after them, certificates of honor were presented, and honorary citizenships were awarded – this was also the case in the cities of Deggendorf and Plattling, in whose catchment area the Mainkofen Sanatorium and Nursing Home is located.

It was quite different for those who tried to shed light on the darkness. They were prevented from investigating, denigrated as nest-foulers, and subjected to disciplinary pressure – such was the case with the medical director of the Eglfing-Haar Sanatorium and Nursing Home, Prof. Gerhard Schmidt. On a website of the Clinics of Upper Bavaria, it states: "...After World War II, Gerhard Schmidt was appointed director of the then Eglfing-Haar Sanatorium and Nursing Home. Schmidt immediately began documenting the horrific 'euthanasia' crimes committed in the institution. During the Nazi dictatorship, around 4,000 people were deported and murdered in killing institutions from the Eglfing-Haar Sanatorium and Nursing Home, systematically starved to death in so-called 'hunger houses' or killed with medication, including 332 children in the so-called 'children's special ward'. [...] There were only a few people who, directly after World War II, found the courage to investigate the crimes and, above all, wanted to inform the public. Prof. Gerhard Schmidt was one of these special and courageous individuals. Right after taking office, he began investigating, trying to alarm the public through an interview with Bavarian Radio. He had the crimes documented, the fates of the people in the hunger houses recorded and written down. [...] However, and this is still shameful and burdensome today, he was dismissed after only one year due to intrigues within the clinic, supported by the then current politics. He was not only dismissed but chased away in disgrace and dishonor."

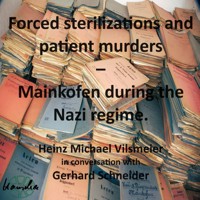

The perpetrators made documents that proved their involvement in forced sterilizations, the killings as part of Action T4, and the starvation of patients – men, women, and children – disappear. They removed the evidence of their crimes wherever possible. Patient records were systematically altered or completely destroyed. In the administrative basement of the Mainkofen Sanatorium and Nursing Home, files, patient records, and incriminating documents were burned for years on the orders of the clinic management. In Mainkofen, there was no one interested in uncovering the truth for decades.

Figure 2. Gerhard Schneider with patient records he found in the administrative basement and saved from planned destruction.

It was only when my conversation partner Gerhard Schneider, the future commercial director of the hospital, began his service as an administrative employee that he came across the piles of files and recognized their significance for potentially clarifying the Nazi crimes in Mainkofen. Gerhard Schneider saved many of the documents from destruction. He took them home, reviewed them, and documented the hidden stories of suffering and perpetrators within them. Gerhard Schneider knew he was treading on dangerously thin ice. It was only many years later, when he had risen to the position of hospital director, that he went public with his findings – and, as expected, he was initially attacked and branded a nest-fouler. But Gerhard demonstrated civil courage and fought to somewhat restore the dignity of the victims of the Nazi racial madness at the Mainkofen Sanatorium and Nursing Home.

Gerhard Schneider is the first to take an interest in and seek to shed light on the dark era of today's Mainkofen District Clinic. It is thanks to his efforts that the victims, on October 28, 2014, the anniversary of the first T4 transport to the Hartheim extermination center, finally received a place of remembrance on the grounds of the Mainkofen District Clinic. – Unlike the perpetrators, Gerhard Schneider has not yet been honored for his courageous commitment.

Once a flagship project of reform psychiatry.

HMV: Mr. Schneider, thank you for taking the time for a conversation today. In what generation are you working here at the Mainkofen Clinic?

GERHARD SCHNEIDER: My grandfather was employed here as a nurse from 1917 to 1954, precisely during the time period I focus on intensively, the time of National Socialism. (...)

HMV: That means your grandfather worked here almost from the very beginning of the clinic?

GERHARD SCHNEIDER: Yes.

HMV: ...I believe it was in 1914...

GERHARD SCHNEIDER: ...1911 is when it opened...

HMV: ...and he started here six years later.

GERHARD SCHNEIDER: Exactly.

HMV: Back then, as you mentioned in another conversation, Mainkofen was a reform project. As such, it was a flagship project in the field of psychiatry. – What distinguished Mainkofen at that time?

Figure 3. Postcard of the Mainkofen Sanatorium and Nursing Home, 2012Source: BKH Mainkofen website.

GERHARD SCHNEIDER: Yes, Mainkofen had a model character that extended beyond Germany at that time. The concept was presented at the World's Fair in Paris as groundbreaking and revolutionary. It represented a departure from "bed treatment," as practiced in Deggendorf and other "insane asylums" until then. "Bed treatment" means treating patients simply by keeping them in bed—though treating is a very euphemistic term. In reality, patients were strapped to their beds, and that was the entire therapy. There were no pharmacological options. This means patients were essentially just stored away for years and decades.

The revolutionary aspect of the Mainkofen concept was active occupational therapy, where patients were not just kept in beds or permanent baths, but rather were actively engaged according to their abilities, particularly in work therapy, and especially in agriculture.

Patients had access to fresh air and activities that were meant to give life a new purpose. The idea was for patients to have an occupation again, so they could feel needed once more. And this concept was realized in Mainkofen, especially through the agricultural approach.

Figure 4. Development plan, Mainkofen Sanatorium and Nursing Home, 1904.Source: Photo archive Gerhard Schneider.

Before it began, Mainkofen was a large agricultural estate. On this land was the Leeb farm, which I still knew as a child. It was an old, large farmstead with livestock.

The Mainkofen concept no longer relied on a prison-like corridor system. The patients were housed in numerous small cottages, where they lived together, in quotation marks, in small groups, where distinctions were already made based on diagnoses, and where the quiet patients were no longer locked up with the restless ones. In the individual buildings, patients were separated according to diagnoses and, of course, also by gender. Gender segregation in psychiatry was practiced until the 1980s.

Figure 5. Occupational therapy around 1930, female patients of the Mainkofen Sanatorium and Nursing Home.Source: BKH Mainkofen website.

And the second approach was total self-sufficiency. In Mainkofen, in addition to a large agricultural operation, there was also a nursery, a butcher shop, a bakery, etc. This means the entire food supply was to be produced by the hospital itself, with the help of employees but primarily through the involvement of the patients.

Figure 6. Occupational therapy around 1930, male patients of the Mainkofen Sanatorium and Nursing Home.Source: BKH Mainkofen website.

HMV: Who was the originator of this certainly progressive model at that time?

GERHARD SCHNEIDER: Around the turn of the century, there was a major reform psychiatric approach by Simon, who came from Erlangen. With family care, this approach also included the first attempts to introduce outpatient treatment. – Why should patients be locked up somewhere for their entire lives? Why not place patients with families, that is, with families outside, and then provide outpatient care from the hospital? This led to the next step, where many patients who would have likely been hospitalized for decades were placed with farmers, companies, and craftsmen, living with families and being cared for on an outpatient basis by caregivers from Mainkofen. This was revolutionary around nineteen hundred! Such approaches are only being rediscovered in recent years, following the "outpatient before inpatient" principle – especially in psychiatry.

HMV: Were the clinic's employees specially trained for this reform approach at that time?

GERHARD SCHNEIDER: Of course, one shouldn't imagine it as it is today, with 90 or 95 percent of the staff being skilled workers. Firstly, there was no standardized nursing education at that time, meaning these so-called nurses, who weren't even called nurses back then, but rather warders. This already indicates that the focus was not on therapy and care but on custody and supervision.

The so-called nurses were trained in in-house schools. It wasn't until the 1930s that there was proper nursing training, which at that time only lasted one year. – So the nursing staff consisted of 90 percent craftsmen, coming from various professions, from cobblers to butchers, from railroad workers to masons, and they were qualified internally. In Mainkofen, starting from the 1930s, these people underwent a one-year nursing training – the qualification, of course, can't be compared with the professionalism of today's training.

HMV: So they didn't bring nursing staff from the "insane asylum" in Deggendorf to Mainkofen?

GERHARD SCHNEIDER: Yes and no! ... We need to take a closer look at the history. Both institutions existed from 1911 to 1934. From then on, Deggendorf was no longer called "District Insane Asylum" but "First Lower Bavarian Sanatorium and Nursing Home," and Mainkofen was also officially called "Second Lower Bavarian Sanatorium and Nursing Home." – The difference was that due to modern psychiatry in Mainkofen, Deggendorf had degenerated into a pure custodial institution. The reason is that all admissions of patients deemed "still curable" were sent to Mainkofen, where they could demonstrate appropriate medical successes because a significantly larger proportion of patients could be discharged.

Figure 7. "First Lower Bavarian Sanatorium and Nursing Home," formerly "District Insane Asylum" in Deggendorf. Source: Photo archive Gerhard Schneider.

And in Deggendorf, there were the so-called nursing cases, meaning the medical involvement there was kept to a minimum. The goal there was not any kind of therapy because these patients were considered untreatable, incurable. – These patients were sent to Deggendorf. And anyone believed to have the potential for improvement or cure through what was then considered modern psychiatry was sent to Mainkofen. – In 1934, Deggendorf was dissolved and simply sold to the Wehrmacht. – According to the Treaty of Versailles, building new barracks was actually prohibited. To circumvent this, they were given camouflage designations, and in Deggendorf, they were called the "Deggendorf Reich Accommodation Office." – Ultimately, the "District Insane Asylum" in Deggendorf was occupied by the SA and later operated as a non-commissioned officers' school.

Figure 8. Mainkofen Sanatorium and Nursing Home.Source: Photo archive Gerhard Schneider.