Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Two Rivers Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

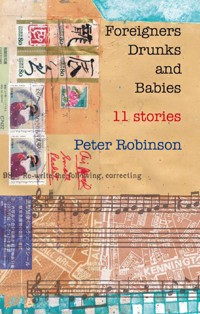

The stories brought together in Foreigners, Drunks and Babies cast the slanting light of a poet's sensibility on the Imperial Academy of an ancient Eastern empire; detail the musical education of a northern realist parish priest and his sons; travel through the West of Ireland with a couple facing various extinctions; spy on the shadowy private life of a Cold War warrior; engage in hand-to-hand fighting with a classroom full of Soviet teachers; follow the adventures of an Italian girl visiting her sick boyfriend in hospital; discover how hard it can be to get a passport for your first-born; find out why everyone pretends you're not there; investigate a seemingly victimless crime; reveal reasons for a Japanese girl's committing suicide; and realize that there's no need to be forgiven for things you didn't know you hadn't done. In this first collection of his imaginative fiction, Peter Robinson, winner of the Cheltenham Prize, the John Florio Prize, and two Poetry Book Society Recommendations for his poems and translations, brings a characteristic perceptiveness, rhythmical accuracy, and vividness of evocation to these eleven examples of what he's been doing in the gaps between his other writings. His new and returning readers may be both surprised and entertained.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 275

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Foreigners, Drunks and Babies

Peter Robinson was born in Salford, Lancashire, in 1953 and grew up mainly in Liverpool. He has degrees from the universities of York and Cambridge. After teaching for many years in Japan, he returned to Europe in 2007 and is currently Professor of English and American Literature at the University of Reading. The poetry editor for Two Rivers Press, author of many books of verse, translations, prose, and literary criticism, he is married with two daughters.

BY THE SAME AUTHOR POETRY

Overdrawn Account

This Other Life

More About the Weather

Entertaining Fates

Leaf-Viewing

Lost and Found

About Time Too

Selected Poems

Ghost Characters

The Look of Goodbye

English Nettles

The Returning Sky PROSE

Untitled Deeds

Spirits of the Stair TRANSLATIONS

The Great Friend and Other Translated Poems

Selected Poetry and Prose of Vittorio Sereni

The Greener Meadow: Selected Poems of Luciano Erba

Poems by Antonia Pozzi INTERVIEWS

Talk about Poetry: Conversations on the Art CRITICISM

In the Circumstances: About Poems and Poets

Poetry, Poets, Readers: Making Things Happen

Twentieth Century Poetry: Selves and Situations

First published in the UK in 2013 by Two Rivers Press

7 Denmark Road, Reading RG1 5PA

www.tworiverspress.com Copyright © Peter Robinson 2013 The right of Peter Robinson to be identified as the author of the work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN (pbk) 978-1-901677-93-5

ISBN (ebook) 978-1-909747-01-2 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Two Rivers Press is represented in the UK by Inpress Ltd and distributed by Central Books. Cover design and illustration by Sally Castle

Text design by Nadja Guggi

Ebook conversion by leeds-ebooks.co.uk

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

An earlier version of ‘Pain Control’ was published on the Brodie Press website in 2006 and ‘A Mystery Murder’ first appeared in The London Magazine (Oct–Nov 2011), reprinted here with kind permission. A great many family, friends, and colleagues have helped in the writing and revising of these stories. I warmly thank them all. And by way of the customary disavowal, let me echo the epigraph to ‘Foreigners, Drunks and Babies’: ‘there are no such people.’

PETER ROBINSON

Foreigners, Drunks and Babies

Eleven Stories

Contents

The Academy Report

Music Lessons

Driving Westward

Lunch with M

Language Schooling

Pain Control

National Lottery

From the Stacks

A Mystery Murder

Foreigners, Drunks and Babies

Indian Summer

for my family

The Academy Report

As, my Lady, you are already too aware, it was in the thirty-sixth year of the late Emperor your father’s reign that the decree came down to our Academy enclave. We were debating, as I well recall, which writer should receive the annual prize in the Imperial Poetry Competition. It was a chore involving much tiresome elaboration of bogus aesthetic principles, rolled out to defend the trifling work of one or other nonentity. Yet, as all of us on the committee perfectly knew, the prize would be awarded to that poet among the three or four most prominent figures who could mysteriously summon the most threatening patronage … The arrival of your father the Emperor’s messenger from the Library on the hill above our lodgings formed a welcome interruption to those tedious deliberations. (But perhaps your ladyship will allow an old man to confess that his habit was, and has always been, to keep out of the poetry prize debate, to peruse a small scroll under the table, and lazily raise a hand when the inevitable winner had emerged as if by prestidigitation from the toppling pile of manuscript there in our midst.)

Interrupting those deliberations, as I say, was the Emperor’s messenger with a request which, given the enormity and burden being placed upon our institution by his Majesty, would first astonish then utterly take us aback. Initiating what would come to be called The Great Anthology Project, our Divine Ruler thereupon required us with all due speed to survey the entire contents of the collections of verses available for sale or held in the many libraries of the Empire. We were to determine for each and every poem found therein whether it fell into the progressive or the retrograde. These were categories that, it need hardly be elaborated for your sake, were minutely specified by his late Majesty, one of the greatest writers and thinkers of this or any other age. Furthermore, after having specified to his satisfaction what exactly was to constitute a progressive or a retrograde poem, his Majesty commanded us to place a distinguishing mark alongside the title of each and every work as – dare I call it? – an Imperial instruction or warning for future generations of readers. The two distinguishing marks, to be embossed onto the paper, were, as you only too well know, a black dagger for the retrograde, and a red poppy-shaped star for the progressive.

Please forgive me if I am labouring the obvious, or, for that matter, elaborating things my Lady knows with all the wisdom and insight of her young years. Your servant is an old man, and I must beg that your Majesty forgive me if I continue to describe what occurred in my hopelessly pleonastic style. It is the only means at my disposal for keeping on at all. There were, as you are too aware, initial difficulties following out the Anthology Decree. As your father the late Emperor wrote in a language not used by ordinary mortals and, while interpreting his works was in truth one of our functions, for this once a certain friction could be sensed among our ranks about what precisely the exclusive categories covered. Moreover, it would not be too much to say that the terms themselves, when scrutinized by a hall full of sages, began to achieve a certain amorphousness of definition. Did the progressive hold exclusive claim to the adventitious and the innovative? If the retrograde were somehow shown to be resourceful, would that automatically transport it into the progressive category? And if a progressive work were also revealed to be conserving certain images from earlier poems, would this oblige it to carry the scar of a black dagger beside its title? My Lady will have already fully appreciated our difficulties without need of my numerous pedantic and painfully pedestrian examples.

Nor did it seem we were to make exception for poems that had once upon a time been hailed as progressive. No, our rule was to be applied across all provinces and for all times. Even before we had begun hiring and training a veritable army of scribes to carry out our task, there were some first signs of the dangers to come. One of our members resigned from the Academy leaving behind a letter in which he lamented the purism that sought to isolate these two (as he benightedly saw it) interdependent concepts. He further inquired whether it made sense to imagine that conserving a style could possibly mean denying it the power to evolve, or whether, for that matter, the new could carry meaning without a vital tradition in which it might be appreciated. They are indeed commonplace arguments, my Lady, but we feared to show his resignation letter to the Emperor. What became of him? The Academy has never in fact been informed of his fate, but suffice to say he disappeared. My heartfelt prayer is that he was able to take his own life in virtuous peace before the forces of correction discovered his whereabouts.

Yet a further difficulty, and one which proved in effect insurmountable, was what to do about your father the Emperor’s own oeuvre. In its sustained lyrical force it is unparalleled; yet it frequently seems shadowed with memories of his Majesty’s enormous reading in the anthologies of his ancestors. His works are full of instruction and sentence, informed with the wisdom of the sages, yet, presented in the highest and most purified dialect, their subtlety is sadly lost on hosts of the Empire’s readers. My Lady, I hope you will allow me to take this occasion to deny categorically the ugly rumour that I know has circulated regarding his deathless compositions, namely the calumny that they were actually assembled by a committee of academicians especially selected for the task. To my knowledge, no such committee has ever existed; and, as you yourself know, the late Emperor was not one to accept advice on life-and-death matters of state, so why ever would he let the inhabitants of our frankly marginal ivory tower tell him how to attune his innermost thoughts?

Naturally, your late father’s work still is – and always will be – held in the highest esteem by the Academy; but, when attempts were made by certain of my late colleagues to interpret the exclusive categories with reference to his Majesty’s work, a further unforeseen difficulty arose. If, as we unanimously agreed, the Emperor’s poetry would be the yardstick of the progressive, then, given that ordinary mortals were not allowed to speak in such tones, did this not imply that all other poetry would be consigned to the retrograde? It seemed impossible that this could be the import and purpose of the Anthology Decree.

Indeed, there was no indication in the Emperor’s commands to us that his poetically inclined subjects, guided by the two categories, should not continue to draw benefit from both the innovative and the conservational. Yet one of the earliest unforeseen consequences of his instituted policy was that debates taking up vast reams of manuscript and scroll began to appear concerning which of the two types of poem the Emperor truly favoured – with his own verse cited and dissected in support of both camps. Indeed it wasn’t long before controversies were flourishing about what type of poem best illustrated the Emperor’s theories and would, therefore, be more likely to receive the accolade in the annual Imperial Competition. My earlier remarks on that yearly chore have surely underlined sufficiently the naïvety of those speculations. Yet some of them were certainly ingenious: it had been pointed out that since the Emperor was then himself the most recent in a Dynasty that has survived centuries of philistine intrigue, he instanced in his own person the flowering of the retrograde. Others proposed the case that the very unintelligibility of his verse to ordinary mortals was a mark of its being indubitably in the realm of the red poppy-shaped stars. It hardly needs adding that had either of these risible arguments reached the ears of the Emperor himself they would have been treated with a minimum of leniency in the inevitably fatal interview between pathetic tyro and divine Authority.

Yet, as you know to your sorrow, my dear Lady, the Emperor’s way of life had begun to alter alarmingly some few years before he delivered (may I be allowed to suggest?) his baleful Decree. Perhaps you yourself have never been informed that he had taken to wearing a monotone monk-like garb through every season. He had further delegated all ceremonial functions to a brilliant actor who would impersonate him when visits occurred from the heads of vassal fiefdoms and the like. After begetting his only child and heir (your most forgiving Majesty), he devoted himself entirely to his studies, building for his Empress the pleasant suburban seaside villa in which you spent your quiet, yet all but fatherless childhood. As you may or may not know, he had commanded your loving mother never to set foot on pain of death in the grounds of his Library on the hill, or, for that matter, the Academy enclave on its lower slopes. There he lived with his retainers and librarians, sometimes talking late into the night with the one or two promising academicians who belonged to his sparse inner circle. Now and then vague rumours would reach us of the subjects they might treat in those nightlong conversations. At word of them, we stood abashed.

Our work continued apace, and, after some years, his cherished Academy was able to report a degree of achievement to the Emperor. We had managed to evaluate the works held in public libraries as well as most of the material then offered in the marketplace. We were already making headway with gaining access to private libraries, and had, on an ad hoc basis, you will understand, begun to standardize individual copies held by private citizens. We were not displeased to note how well the Academy had responded to these unprecedented challenges, and sincerely hoped that the Emperor would agree. Sadly, however, submitting our interim report on those labours had the opposite effect to that intended. The Emperor soon made it known to us he wished his project extended to all works announced as forthcoming from the Empire’s publishing houses.

The mute and glorious departed could not, of course, object to having their verses marked with our daggers and poppies. The few living whose works were illustrious enough to be readily accessible found they were obliged to stomach the indignity without any court of appeal. But the extension of our mandate to works not quite yet available introduced a new dimension to our difficulties. Having one’s verses branded with a thicket of daggers would seriously damage their reputation and, consequentially, sales. Our peaceful Academy enclave situated within the Imperial Botanic Gardens became the stage for protests by schools of young poets carrying banners and wearing various colours of helmet. When they were not trying to interrupt our efforts, they were staging pitched battles between their rival factions. It was all most unseemly. Satirical verses were circulated anonymously in which we were personally attacked. None of us escaped. Some members were physically jostled on their climb up the hill-slope towards the Library’s outer gates. Cases emerged of our scribes being offered, and of receiving, bribes to increase the number of red poppies in a given slim volume. This, I fear, is what may have happened in the unfortunate case of the book thought to contain verses dedicated, with however extreme obliqueness, to your Majesty when still a budding girl. Of its luckless author’s fate I’m afraid I can tell your Highness nothing.

Rumours of our difficulties at the Academy enclave reached the ears of political cliques in and around the capital. The quality of their writing in general need not concern us, even less the specific merits of their various ventures into the composition of tendentiously original folktales. What did cause rising concern at the time was the impact of their ignorance of literary refinements on the already vexed questions surrounding our work. There was quite naturally a concerted effort to associate each of the two categories with specific court factions – something which, I hasten to note, was never part of the Emperor’s original definitions – thus clouding further the issues involved, and further complicating the emotions stirred by each specific adjudication.

This was bad enough, but it was aggravated by the eventual involvement of the priests who, until then, had been benignly smiling upon our efforts from their temples on the far side of the city, beyond our famous river rolling between its populous cliffs and the main thoroughfares of the markets. Taking advantage of their autonomy and elaborate structures of protection and defence, the priests weighed in on the side of the retrograde, arguing with a certain justification that the category was unfairly discriminated against. Some of their followers are, of course, utterly fanatical. There were death-threats hurled at academicians who appeared over-inclined to award red poppies. This was when my dear wife and our poor children were still with me. There were attempts on the lives of rival anthologists – not for the usual reason (one or another poet being somehow overlooked), but because they were either thought too inclined to include works bound to be garnished with a dagger, or else favour ones as likely to be stamped with a star.

Naturally these death-threats further depleted our numbers, whether because their victims went into hiding or because the threats were carried out, I do not wish to speculate. How I have survived, my Lady, I nightly ask myself among my prayers. Perhaps those years of quietly studying one of our classics under the table at the Poetry Competition debates has stood me in good stead. But word, my Lady, has recently reached me from your outer provinces beyond the White Mountains that some whose self-esteem has been so trampled by these developments are gathering supporters around them. I fear our Literary World may be descending into a vicious chaos. No, it has not happened; but I fear it. My Lady, I fear it.

Finally, your Majesty, I must compel myself to speak about the treasury. Although the monies accruing from the tax on literature are not vast, and despite a certain slight increase in public interest when the Emperor’s Decree was first made public, there has been a sharp subsequent decline in revenues from the markets. One plausible explanation for this may be that the black daggers have driven readers away from certain kinds of poem while the red poppies have not succeeded in igniting an enthusiasm for other kinds. The Academy’s various efforts to promote literature among the distracted populace (such as the institution of an Imperial Poetry Day) have made little real impact – beyond the inevitable one of flattering those featured poets who enjoy powerful patronage while fuelling the already smouldering resentments of those who do not. Many of the hoi polloi with whom I have been in any sort of contact during this difficult period have expressed their bemusement or indifference. Admittedly, their understandings of the matter have little significance, and need not detain us here.

However, the cost to the Academy of recruiting and training scribes and clerks, the journeys undertaken through the length and breadth of the Empire, the additional expenses incurred in policing the Academy enclave and providing protection for academicians, has been nothing short of ruinous. Though requests were made to the Emperor for subventions in his declining years, it was by that stage far too late. He had turned away from the world. He was intent on the composition of his deathless cycles of last poems. It has been whispered he expired a disappointed man. Yet who could have predicted that so much misery and waste of talent would come from an effort to determine once and for all certain literary values? Who could have thought that to let such values flow with the times and to leave them in the casual care of those who need them most would prove the safer and more enlightened policy?

And thus, my Lady, it is with the most miserable regret and humble supplication that I write on behalf of those who remain in the Academy to beg your indulgence in granting our request. We most dearly beg that your Majesty temporarily suspend (should your Majesty think fit) the operation of the late Emperor your father’s Anthology Decree.

Many years have now passed since I submitted the Academy’s report to my Lady (who would so quickly blossom into such a fine teller of tales) and it had, I am pleased to relate, more than the desired consequence. Not only did our young Empress revoke her father’s Decree; in her wisdom, she ordered us to set about removing the daggers and poppies from all the poetry collections that had been – I allow myself the liberty of a man surely on his deathbed – defaced by that meddlesome Imperial command. She even designed a scalpel-like knife, adapted from one of those used by her Court beauticians, to help us fulfill our duty to the Empire’s culture. It was yet again an arduous task, once more almost bringing our long-suffering Academy to its knees, what with such considerations as the hire and control of workers travelling far and wide to undertake so menial an operation. Without an interim subvention from the Empress herself, the so-called Special Poetry Award, I am by no means sure that we would have been able to bring to completion her far more enlightened Decree.

We did our best; but let me end with a word in your ear. Should you, dear understanding reader, by chance or good fortune come across any of the very few copies that must have escaped our vigilance, be sure to treat it with the utmost care. The two or three so far surfacing in the markets for such things have been described in catalogues and leaflets, like the one I’m holding at arm’s length before me, as, and I quote, ‘quite literally priceless’.

Music Lessons

Mr King would soon blow full time. You can see the whistle gleaming in his hand. He puts it to his lips. Mr King’s face is gaunt and wrinkled, permanently yellowed from jaundice. He was a fighter pilot in the war.

At the far end of a cindery field stretching down one side of a raised canal bank, your team is mounting its final attack. Your side’s a goal down, but there’s still time. You’re the goalie. Sometimes you play on the wing. It’s cold standing in the goalmouth. Your clogged soles suck and squelch as they lift out of the ill-drained pitch.

Inflating his cheeks, Mr King blows a single, high-pitched note and he shoos the boys off with his arms. Your stomach feels as heavy as your feet. The metal rugby boot studs clatter on flaked, subsiding flags. It’ll take a bare twelve minutes to get back home.

You cross the vicarage’s oval front lawn and ring its blue front door bell. Mum welcomes you back, but you’ve scurried right past her in the porch, and make down the hallway for the dining room. There the upright piano silently takes up its corner. You’ve got just half an hour.

First, the theory: taking a tram-lined exercise book from the scuffed leather case with its metal bar fastener hooked over the handles, you sit down at the dining table. The book of questions and the clean pages of staves lie cushioned on the thick brown felt, covered by a tablecloth at meal times. The felt is to save the wood from further heat rings, spills and scratches.

It will take you fifteen minutes to finish the exercises if you keep concentrated on the job. Some stewing steak, browning in the pressure-cooker, loudly sizzles. It’s going to be hotpot, and you can’t wait.

Counting the lines and spaces, you transpose phrases from one key to another; calculate major and minor intervals; guess the time-signatures for a few groups of notes, scratching in the bar lines, double ones at the end of each example. With no time to play over the passages, you complete the tunes by writing in resolving scales, mechanically arriving at runs of notes that dip under or hover over the tonic, sliding through a dominant seventh below, or a tone above, rising or toppling on to each final chord. You check the agreements with key and time signatures, then put the top back on the fountain pen and blot the page with a soft sheet that sustains yet another bluish ghosting of notes and other marks.

Slumping back in the chair, you snatch a moment to survey your handiwork. There are the lines of crotchets, quavers, semi-breves and minims, the clefs, rests and signatures, with here and there a crossing out or smudge. But you can’t help regretting that the tails and strokes, the filled-in ovals sitting on or straddling the lines, never look so sure or evenly spaced as in the printed scores.

If only they could look right too! Closing the manuscript book and questions and returning them to the scuffed music bag brings a further sinking to the heart. Will you ever learn? But there’s no time like the present, so you sit down at the piano and lift the keyboard lid. The maroon hard cover of Hymns Ancient and Modern, the detail from Piero della Francesca’s ‘Nativity’ on The Penguin Book of English Madrigals, assorted dingy piano tutors, a bowl of fruit, and a white table lamp (which shivers distinctly at each note struck) top the dark wood box of the instrument.

Now the most likely piece lies open on the stand, the brass hooks restraining its pages. For the first time this week you study the score. Initially Miss Austin had given you Edith Horne’s exercises, scales that are to familiarize fingers with the keys: the yellowed and dirt-ingrained ivory of the white notes, the more remote and less frequently visited black ones. The C above middle-C makes only a light, high, almost inaudible tinkling sound. The G below it stays down when you press it, and has to be deftly flicked level with its neighbours by a fingernail after the note has been struck. When the scales and exercises don’t produce the slightest improvement in your application, you’re tempted with books of tunes a boy might be expected to like: popular lyrics, light classics, film themes … Now you’re groping your way through The Sound of Music.

This Wednesday, as your eyes attempt to decipher the thick black towers of bass-clef chords, to co-ordinate them with the slopes and ranges of the melody, you’re trying to make out through a cacophony of forgotten incidentals, unsyncopated hands, and halting rhythm, ‘Doe, a deer, a female deer’ – its catchy lilt and cadence; later, Herb Alpert’s ‘Spanish Flea’; and, with only a few minutes still to spare, ‘Somewhere over the Rainbow’. But it’s too late to hope for better now. You race out through the kitchen and, for Mum, let fall a loud ‘Goodbye.’ She’ll have responded with a ‘Goodbye, dear’ – but too slowly for the words to reach you before you slam the back door, their sound hanging as if unwanted in the all but empty vicarage, like a cough between movements in some hushed concert hall.

You leap down the stone steps of the back door porch and feel the small cobbles of the yard through the soles of your shoes, cobbles that had rung to the hooves and wheels of the minister’s horse and trap. The grille-like fodder baskets are still there in the stables where Dad parks the family’s grey-green Morris Oxford. The upper floor was really once a hayloft. You’d seen the trapdoors in the ceiling above the fodder baskets where they used to push the hay. The place is strictly out of bounds.

‘The floorboards aren’t safe,’ Dad said, ‘and there’s an end of it.’

The great blue double doors to the yard stand open and you walk on round the oval path of the vicarage garden. It’s like a tiny racetrack made of red shale. There you and your brother would go for spins on bikes and crash, scraping your knees, which would be streaked with two kinds of red, the blood and the grit.

St Catherine’s Street is unadopted, its cobbles reaching past the church gate as far as the vicarage drive, but no further, petering out into cinders, rocks, and mud. At the bottom of the street, with Mr Hill’s corner shop still open for everything, you can see where the brew falls sharply to lock-ups and allotments: ramshackle planking and tarpaulin with smashed fences and overgrown plots, places for playing war with friends from school.

Rathbone’s bread factory is more distant, beside the flights of locks in the canal; on the other bank, beyond its tow path, there rise the Wigan Alps, a high plateau of pale grey slag, the peaks giving this landmark its wry local name. Across these ashen tracts towards the railway lines are red brick ruins of abandoned workings, dilapidated pit-heads; their cable wheels and conveyors, corrugated iron roofs, and steel winding gear all dismantled for scrap. Only the walls of former outbuildings, stores, baths, and the offices have been left to the gangs of the surroundings, the Mount Pleasant district.

When Mum and Dad invited you boys into their bedroom one morning and told you the family was moving to a new parish in a town called Wigan where the coal mines were, you didn’t want to go. It was frightening to think of living in a place covered with bottomless holes in the ground. But they’d said not to be silly: it was quite safe. Now you’d seen the curious circular walls, three times your height, with the sharp glass of bottles cemented on their tops, and had been told by Hawthorne, one of the boys at school, that these were the old pits.

Not even the bravest or stupidest in the gang would climb those walls. It would be worse than falling into the canal, being sucked down, dragged under by the water rushing through the vents in the slimy green lock gates, or trapped in the mud at the bottom where brass beds and mattresses, bike frames and prams, even old pianos, all brown with rust and mud, would catch a boy’s heavy feet and hold him under until, as it said in the Bible, he woke up dead.

The steps lead through a crack in the terrace next to Hawthorne’s house. There are three long flights, and two main roads to cross. You always want to walk slowly, be as late as you dare, since every moment will lessen the harrowing; but gravity, which you’d done in science with Mr King, makes it hard not to go down those steps without breaking into a scamper. Dropping, as tardily as possible, you recite the terms you expect to be quizzed on. Some you’d already learned from the theory book. They were in Italian: allegro, prestissimo, andante, vivace, con brio, molto lento, poco a poco, da capo al fine. But there were always more of these mysterious expressions to repeat once more to the end.

With a regular beat, the soles of your shoes strike the worn stone steps, sometimes splashing in the shallow remnants of recent breaks in the weather the south Lancashire plain’s been enjoying. How many times have you descended into Hell? That’s what your brother Andrew calls it. And how many times will you have to rise again? A memory catches you unawares as you trip down a further flight of steps. You’re about the height of a bedside table. There are grey-carpeted stairs leading to the right and a bedroom door near the top of them. It opens into a small room filled with a vast double bed. The bed has a curved utility-style veneered headboard. Lying under the covers is your dad, his head down at eye level. Someone must have told you he is ill.

There’s a small round metal tin on the table near Dad’s head. Fiery-devil it says on the tin. The lid shows a bright red dancing figure with glinting eyes and a leering mouth, a sharp toasting fork in one hand and an arrowed tail. Why do you remember that? Is it because Dad was a curate then? Perhaps you asked Mum what the tin was. ‘Embrocation,’ she said: something she rubs on his back. But how can something with the Devil on it make him feel better?

That was the first time you thought of your father as mortal. He was ill. He might die. Even though he was a clergyman he too could go to Hell if he were bad! How many times have you climbed those flights of steps, after promising to practise as you leave the lesson, and then let it slip as soon as you’re home, so that the music case can just go and rot for another week? People could encourage you, or they could threaten. It was as though the latter, or personal dislike, or an aversion of some kind, would make you not even so much as lift a finger.

So it’s with bone-idle stubbornness that you view the prospect of learning to play the piano. For six days out of seven you’ll bask in that attitude. Then, for a few hours on Wednesdays, you have to sweat it out.

‘You’ll regret it when you’re older,’ Dad said. ‘I never had your opportunity when I was a boy, and I regret it, bitterly.’

But why then did Mum, who had musical parents, hardly ever play?

‘I love all kinds of music,’ she’d say. ‘If only I had more time …’