11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

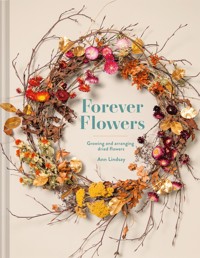

Learn how to grow and dry flowers, plants and herbs to createdried floral arrangements that will breathe fresh life and style into your home without breaking the bank! In this contemporary reimagining of a timeless craft, Ann Lindsay Mitchell guides you through the method of drying flowers in three achievable steps: growing, drying and arranging. This excellent source of practical advice is explored through an encyclopaedic list of flowers and foliage with specific information on how to grow, cut and dry them to best effect. From coffee table posies and large arrangements to hand tied-gift bunches and wedding bouquets, beautiful photography accompanies guidance to creating arrangements with your newly dried flowers. Filled with delicate watercolour illustrations alongside stunning photography of both simple and elaborate floral arrangements, Forever Flowers is an exceptional guide to growing, drying and arranging. Suitable for both experienced professionals and hopeful newcomers to the art of drying flowers, the information in the book is an invaluable resource for all to reference and return to. Anyone can create everlasting arrangements for friends, home or occasions that can be cherished for years to come.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 158

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Introduction

Drying

Greenery

Drying methods

Plants

Annuals

Perennials, biennials, bulbs and small shrubs

Shrubs and trees

Wild plants and herbs

Cultivated vegetables and herbs

Other farm crops

Arrangements

Preparing material

Arranging

Index of plants

INTRODUCTION

I was perched leaning over an old mahogany desk within the library of the Royal Botanic Garden in Edinburgh, gingerly leafing through the very precious 200-year-old diary of an intrepid plant collector. Within the pages of spidery handwriting, the carefully recorded observatory descriptions crept up the edges of the wafer-thin paper, as though to use every inch of space.

Suddenly, a skeletal leaf slid sideways towards the spine of the book, leaving a residue of seeds clinging to the page. Although initially startled, as one is emphatically not supposed to disturb such valuable books, I then gazed at the leaf and pondered. Was I the first person to turn the page since the diarist had inserted the leaf? I was entranced. The lacy leaf was exquisite. Perhaps the seeds might, even now, be viable.

Who had picked this specimen? What memories did it hold? What patch of earth had nurtured something so ethereal? What birds and insects, perhaps, had brushed against this plant?

Gazing at a flower or leaf picked centuries ago, or even months or a year ago, is a magical moment. Memories galore are contained within.

Drying flowers can be just like that. They may not last for centuries, like the leaf I hardly dared breathe upon, but they certainly do last for many moons. And ‘they are light enough for the fairies to hold’, as one small girl told me solemnly.

So, in an age where not enough is valued for longevity, drying flowers happily bucks short-sighted trends.

For those with a garden, all summer long there is a delectable surfeit, and then all too abruptly it is over. Flowers in winter seem a real winner in tricking nature and preserving memories and one’s handiwork.

Nothing boosts morale better than looking into the midst of a bunch of brilliant helichrysums in late January – except a ticket to the Caribbean. But they do require effort and a little know-how. Even seasoned gardeners balk at the idea of which plants to grow, when to pick, how to dry, where to dry them, how to store them and then, finally, how to arrange them. Where on earth do you start?

Well, before you sink your hands into the earth, read the beginning of this book, and the whole subject should become clearer.

The middle sections, on the actual plants to grow, can be dipped into and items picked up from time to time, rather like a cookery book. The plants are listed in alphabetical order under their Latin names, and common names are given in brackets.

The end section is an easy beginners’ guide to what to do with the plants when they have been grown, picked, hung, pressed and dried.

Whether you have a large garden, a small one, a patio, or just some pot plants, you can still make use of this book.

Ever since that startling moment with the leaf within the old diary, I often enclose a pressed flower within the pages of a book, just to remind myself of when and where I read it. Many an old second-hand gardening book handed on to me has no surprise more heartwarming than the unexpected fluttering out of a few petals and leaves within the relevant chapter; a true connection with the original owner. And nothing seems to please friends and family more than doing the same when offering a book as a present.

DRYING

Flowers

Keep upmost in your mind the word ‘quantity’ when the idea of drying flowers is about to become a reality; imagine drying in armfuls rather than small bunches. By the very act of drying, many leaves, flowers and seedheads may shrink by around 50 percent. This does not mean that you have to find an armful rather than a bunch every time you hang something up to dry, but it does mean that you should dry much, much more than you think you may use. You certainly will!

For many people, the attraction of dried flowers in shop windows is that their generous profusion looks so temptingly lush, bountiful and extravagant. It is often disappointing therefore, as you may well have discovered, to buy one pretty bunch, take it home, and try to arrange the flowers. Many people try to spread this one small bouquet around, striving to make it look as generous as possible by popping the odd half-dozen flowers into at least a couple of containers. This is a mistake, and hints on how to arrange are detailed later in this book. The main point is, though, that one small bunch ends up looking quite lost, unless you add to it yourself with greenery, seedheads and even ‘weeds’.

Dried flowers can be expensive, because they are both labour-intensive and prey to unseasonal wet and windy growing seasons. These high prices are a great incentive for growing and drying your own flowers; unless you have a great deal of money to spare you will never achieve the beautiful image of great vases of flowers, unless you grow them yourself.

So, how do you launch yourself into drying in quantity?

An easy first step is to pad out the shopbought blooms with as much dried greenery as possible, and if you can’t dry many flowers because you have no garden or time, then gathering greenery and drying as much as possible (many weeds dry well) is a good start. You will undoubtedly use it all.

This book contains many different plants from which you can easily dry the flowers, leaves or seedheads, or sometimes all three. Also included are herbs, which, while obviously not being dried flowers, will provide an interesting scent for at least the first month or so.

For those with a garden

If you have a garden, then you can grow as many of the plants listed in the book as you like. The majority can be grown in any soil, and under most climatic conditions. Within your garden there may already be many species which you were unaware could be dried; or perhaps you did not realize that some are so easy to grow, or where you can obtain the seeds. All this information is contained within this book.

Be encouraged to grow plenty, and attempt to dry as much material as you can. Look around also for material which you do not have, or which you have not enough room to grow. Read on for ideas on how to increase your stock for drying.

For those without a garden

If you do not have a garden, but have perhaps a patio or terrace, try growing some of the annuals as pot plants, and try also pinching leaves for drying from, for example, coleus or ferns, and pressing them. Few prolific pot plants will miss the odd leaf. Potgrown hydrangeas and Dianthus caryophyllus can provide a couple of blooms. Alliums, Acanthus mollis and celosias can be grown very well in outdoor pots.

Alternatively, you can buy flowers from a florist specifically in order to dry them. For example, bunches of gypsophila, or herbs, can often be bought at the end of a Saturday for reduced prices. Check through this book for which plants and flowers will dry, and then you may be in a position to snap up a few bargains.

If all this effort to gather armfuls of material to dry is still beginning to sound rather expensive and extravagant, and you can neither grow your own nor afford to buy flowers specifically for drying, then look around for free flowers.

The simplest way might be to ask friends with large gardens (or larger than yours, anyway) to spare a few for you. You can always return a dried assorted bunch one day as a present. Also, keep your eyes open for any garden or public park that has a professional gardener wandering around inside it. The most likely places are the public parks that contain flower beds, although many leaves, branches and seedheads of weeds can be dried as well. Gardeners are usually the most generous of people, only too willing to give away samples of their care to anyone who shows interest: ‘that freemasonry of gardeners’, as Vita Sackville-West described it.

Other possible sources in Britain are National Trust gardens, and others which throw open their gates under charitable schemes once or twice a year. By offering a donation to the charity scheme supported by a particular garden, you might well be fortunate.

Most professional gardeners, and here I include anyone who is being paid for lifting a fork, are a jump ahead of us amateurs. Herbaceous borders are quite properly chopped down and tidied up before they are past their best, unlike my own, since I cannot bear to cut down anything until the last flower has vanished. If you keep an eye firmly attuned to the cycle of the gardening year, you could, for example, negotiate a bunch of delphiniums, Stachys lanata or Aconitum still in reasonable enough condition to dry.

If you can persuade someone to let you have some prunings to take home, you will probably have to be willing to go along and collect them as soon as they are chopped down, or very soon afterwards. Not only will gardeners want to dispose of rubbish as fast as possible, but your precious flower heads will quickly be damaged after lying in a wheelbarrow for a few hours.

Roses are well worth considering. Most parks grow hybrid teas and floribundas, many of which can be dried. When roses are pruned in the autumn they are still usually producing buds, and it is buds that can best be dried. The most tactful way to accept a gift of rose prunings is to welcome the lot, take home the entire barrowload and sort them out. And, since rose prunings are usually burnt or shredded, you are not depriving next year’s blooms of sustenance. Consult this book for plants which produce material that can be dried, then look out for those plants in other gardens or parks; cultivate your garden contacts as you would cultivate your flowers.

Finding more material for nothing

In your efforts to bulk out your collection of material for drying, do not ignore flowers, leaves and seedheads from the wild. While not wishing to encourage anyone to rip up rare plants, there is a wealth of material growing not only in the countryside, but on road verges, riversides and derelict ground, which can be dried beautifully. No item suggested in this book is an endangered species, but even so, always make sure that you never pick the only flower or seedhead of that type, and never pull anything up by the roots. Read the section on wild plants and herbs (here) and start searching.

GREENERY

Most people will be surprised by the amount of greenery that I recommend for drying. Why, apart from the fact that most of it is plenteous and encouragingly free, does one need to dry and preserve so much that remains green?

My offer, once, to arrange the flowers in our local church (so cold in this northern spot that the water usually freezes in the vase during the winter months) with the suggestion that I should bring a posy of dried flowers was politely declined. The lady in question assured me that she did not care greatly for dried flowers and never had, despite her obvious and extensive knowledge of gardening and flowers.

However, a couple of weeks and several feet of snow later, she must have concluded that this was not such a bad notion after all, as a narrow-necked embossed brass pitcher had been filled with a rigidly symmetrical array of teasels, bullrushes and honesty seedpods. My three-year-old son had to be restrained from using one as a sword! Once installed, the flowers stayed and stayed, I recall, for weeks.

A month later, I realized that what was predominantly wrong with this arrangement was its sterility, which arose from the lack of any form of green – the symbol of growth.

You can judge this for yourself. Buy or pick a small bunch of flowers, dried and devoid of green. Then surround them with a few ferns, for example; the difference is magical. Another bonus in having plenty of leaves around a bunch of flowers is that not only do they make a smallish posy go a lot further, but they make life much easier when you are trying to concoct an effective arrangement.

This is not to say that all dried arrangements will always need green. Stunning things can be done without a trace of greenery, as can be clearly seen from the photographs in this book. It is just that greenery is essential to complement many dried flowers, and somehow produces arrangements that, in the long term, are softer on the eye.

Most of the selections listed in this book can be successfully dried by pressing. A few can be hung-dried. Once again, think in bulk, and press or hang as much as you can.

What appeals to me most is the rather effortless, English country-house look of a bundle of sweet-smelling blooms, freshly gathered while wandering up the garden path and lowered promptly into an informal container. To achieve this confident look, I finally found that it is best to treat dried flowers in exactly the same way as fresh ones, and to pick and select leaves to surround the flowers and mingle with them. Not only are lots of leaves, even when still stiff from being pressed, perfect for bulking out a small selection of flowers, they are also adept at hiding bare stems or wire.

On the other hand, some of the wispy arrangements in this book demonstrate just how exquisite a single bloom can be. Eric Bremner, whose inspirational arrangements enhance this book, quoted a Japanese friend and Ikebana expert who told him to ‘leave spaces so that the butterflies drift through’ – he loved that idea and so do I.

You can never have enough greenery. It is amazing how even a tiny bunch of flowers surrounded by leaves looks passable as a present. Even if you have masses left over – I once pressed a forest of ferns under the spare-room carpet, which came into their own as a complete arrangement for a seldom used fireplace – you will find a use for them. You will always be grateful to stumble across an extra unexpected bunch.

DRYING METHODS

Picking and preparing for drying

The golden rule is to pick a little every day, if you are collecting material from your garden. This way it takes only a few minutes of your time and yet the material will mount up very quickly.

Try to hang, prop upright, or press as soon as you pick, or at least on the same day. If you cannot, then stand your flowers in cold water in a cool place.

Each plant listed in this book has instructions on exactly when to pick, but geographical situations, gardens, plants and the weather can be so variable that it is impossible to give foolproof instructions.

If in doubt, pick a couple of flowers at different stages, stick on a couple of labels with, for example, ‘open’ and ‘half-open’ written on them, and dry the flowers to see what happens. One or the other will look preferable, but I confess that I rarely have the ruthlessness to throw anything out … it just finds its way to the back of the bunch. Single petals can be used to decorate cards, or form the basis of potpourri.

Stripping off leaves Most flowers or greenery need to have their leaves stripped off, at least at the bottom of the stem. I tend to leave one or two leaves up by the flower head, and at least 5–7.5cm (2–3in) of leafy stem. After all, one can always strip them off later. You must, however, always strip off leaves from the base of the stem, where the tying is done. If the material is to be propped upright, you must strip off the leaves below the upper level of the vase, leaving only bare stems within the container. Crushed leaves always look unattractive and prolong the drying time; they also cause the base of the stems to rot.

For pressing, it is wise to leave a clear 2.5cm (1in) or so of stem, otherwise there is nothing to use as a stake for sticking into wire.

Arranging for drying

Flowers that are to be hung, or propped upright, should be arranged on a table, or in your hands, so that the heads are not all crushed together, but staggered, and then tied up so that they look like a bunch. This will save time later on.

Trim off the stems so that they are all the same length, as this makes storage and arranging a lot easier.

For large flowers, such as peonies or hydrangeas, hang no more than three or four together. For small flowers, such as Lonas inodora, Xeranthemum or Centaurea cyanus, you can arrange them into small posies, by type, so that the effect is akin to the head of a larger flower. In this way you can make almost ‘instant’ arrangements later on.

For larger branches, such as the seedheads of Buddleja, use their natural V-shape to hang over a nail and leave them to dry.

You can also secure stems to a clothes airer using pegs and leave in an unused corner of a room to dry.

Danger signs

If you are aiming to dry as much material as possible outside, or in a room relying on being heated by sunlight, and we have a less than perfect summer, watch carefully for the remotest sign of mildew or mould.

If this does happen – and it will almost certainly start near to the base of the stems – you must be totally ruthless and throw away anything affected, and all those adjacent. Then, if possible, move any other nearby bunches to a faster-drying spot.

Sunlight, of course, bleaches very effectively, but perhaps consider turning this to your advantage? Many bleached items look wonderful grouped together.

Storing and saving time

If you have a shady room with a ceiling large enough to hold all your dried flowers, the easiest thing is to leave them there until they need to be used. Hung up, they can come to no damage, and will not be forgotten.

If space is limited, and you have to operate a shift system in the airing cupboard, for example, then store the dried bunches, wrapped in paper, in cardboard boxes.