Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

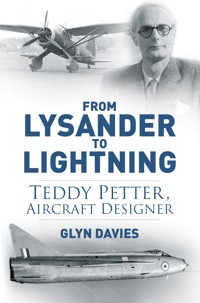

The Lysander, Canberra, Lightning and Folland Gnat are massive names in the world of aviation. Only three aspects bound together these top-class aircraft: they were each radical in design, they were all successful in Britain and overseas, and they were all born of the genius of Teddy Petter. This book tells the story of Petter's life and family, with his ability to inspire the loyalty of his teams, as well as his tendencies and his eccentricities, right down to his retirement to a religious commune in France. Here Glyn Davies not only explores Petter's life, but also expands on the nature of his remarkable aircraft and why they are so legendary.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 248

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Title Page

Foreword

Preface

Introduction

1 Four Generations of Petter Engineers, 1840–1935

2 The Westland Years: The Lysander, 1935–1944

3 The Westland Years: The Whirlwind and the Welkin, 1938–1942

4 The English Electric Years: The Canberra, 1944–1950

5 The English Electric Years: The P1 and Lightning, 1948–1950

6 The Folland Years: The Midge and the Gnat, 1950–1959

7 The Final Years, 1960–1968

Appendix 1 Basic Aerodynamics

Appendix 2 Basic Aerostructures

Notes

Copyright

FOREWORD

Few interests are as all consuming as aviation. To be able to fly has been the dream of mankind for centuries. It has been the stuff of folklore, the pursuit of the brave, and the goal of the engineer.

Warfare, travel, exploration and sport have all been affected. The pursuit of flight dominated the twentieth century to shape our modern world.

The story of aviation has largely centred on the deeds of the heroic pilots, but the miracle of flight is primarily due to the work of engineers. Only a select few aircraft designers have come to the fore to become household names, like R.J. Mitchell, Sydney Camm or Barnes Wallis.

One name that has remained in obscurity for some time is that of William Edward Willoughby Petter.

William Edward Willoughby Petter was the son of Sir Ernest Petter, founder and chairman of Westland. He was brought into the company by his father, and his rapid rise to a senior position was an unbridled display of nepotism. However, ‘Teddy’ Petter, as he was known, did not need any help to stand out as a talented engineer and his name is associated with several famous aircraft such as Lysander, Whirlwind, Welkin, Canberra, Lightning and Gnat.

He was intensely shy and reserved, totally ill at ease when in company or the centre of attention. He was camera shy, appeared to be incapable of giving praise and did not suffer anyone he deemed to be a fool, and in his opinion there were many, including some of his colleagues, who fell into that category. In 2015, Westland will celebrate 100 years of continuous operation as an aircraft company, and it was felt that this would be an appropriate time to produce a biography for Teddy Petter.

Professor Glyn Davies has indeed filled the gap; not only does he discuss the technicalities of aircraft design in some detail, but he also gives a deeper insight into the character of ‘a difficult man to know and a hard man to work with’.

I feel that some comment must be made concerning Petter’s involvement in the Lightning. He was primarily involved during the conceptual stage that resulted in its unique configuration, the awesome operational fighter came later.

This book is not simply a catalogue of the aircraft design and problems solved, it also relates a tragic human story. In later life Petter’s wife contracted Parkinson’s disease and, in the course of his efforts to find a cure, this strong-minded, intelligent man fell into the clutches of a medical religious charlatan. I suspect that by the time readers have finished with this book there will not be a dry eye in the house.

At last the Petter story has been told, and Teddy Petter can take the place in history he deserves

David Gibbings MBE, FRAeS, 2014

Retired Flight Test Engineer and WESTLAND Historian

PREFACE

In 1955 I started work in the advanced projects office at the (then) Bristol Aeroplane Company, working on the research aircraft type 188 (the all-steel thin-winged Canberra!) and the type 223 (to become Concorde). At this time the name W.E.W. Petter had already become legendary, and he was known to be a creative genius but with a strange, eccentric character. In 1959 I emigrated to Sydney for six years, returning as an academic to the department of Aeronautics at Imperial College, London. During my forty-five years at Imperial, I worked on many contracts with Industry but the name of ‘Teddy’ Petter never cropped up. His name was nowhere near as famous to the public as were his aircraft. The Lysander became known for its adventurous trips to occupied France, to deliver and take back intelligence agents; the Canberra was the first English jet bomber and was continually in the newspapers when it shattered numerous world records for long-distance flights to most countries around the globe; and the Gnat became famous when it was adopted by the RAF as its aerobatic display team, the Red Arrows.

These aircraft were all radical designs, being totally new in concept, and nothing like anything designed before or after. They were also commercially successful. Uniquely they were designed by one man at different companies as he moved from Westland at Yeovil to English Electric at Warton, and finally to Follands at Hamble. This man was clearly a radical thinker with a character to match. He was intolerant of second-class engineers, of managers, and of Government officials, so much so that eventually he had to move on to another company and leave his frustrations behind. His move to Follands at Hamble was his final one, where he became the Managing Director and subservient only to the Board of Directors. Only when Follands were taken over by Hawker Siddeley did he resign and leave England never to return. On retiring myself I did think that there was here a story to be told.

This book tries to capture the personality and ability of an innovative designer, but also why his aircraft were so original in their overall design configuration, their aerodynamics, their structures and their control systems. Some of these features are therefore described in depth, referring to detailed appendices where necessary. Petter’s designs are compared with other international contemporary aircraft, and shown to be well ahead of their time.

I did wonder why no biography had ever been written about this strange man, and discovered that in 1991 a book had been compiled consisting of articles from a dozen of his colleagues. This was never published, so I decided to write this biography using much of the material from the unpublished work. I hope I have done justice to a man who clearly inspired all who worked for him in industry, and yet whose final days were very sad, to say the least.

I should like to acknowledge the exceptional help given by Dave Gibbings of Westland Heritage, without whom I would not have taken on the task of this biography, and who provided much of the information and illustrations of Petter’s designs at Yeovil. Thanks also to Dennis Leyland of BAESystems Heritage for information and photographs of the aircraft at English Electric, Warton. It is not possible directly to thank Robert Page, Roy Fowler, and Adrian Page, as they are sadly no longer with us, but they compiled a biography of Petter in the form of contributions from twelve of his co-workers and others. It was never published, but is widely cited in this book. I am also most grateful to English Electric colleagues of Petter, Frank Roe (Aerodynamics, and former MD) and Alan Constantine (former Assistant Designer), for confirming or correcting parts of the English Electric chapters. I received much help from libraries, including the British Library, but particularly from Brian Riddle at the National Aerospace Library at Farnborough. I would like to thank Andrew Doyle, Head of Content at Flightgobal for the many cutaway drawings appearing in past Flight magazines. Hugh Evans should be thanked for acting as an intended reader of each chapter.

I must thank all my colleagues at Imperial College, and countless students and postgraduates who kept alive my interests in aeronautical research and design.

Finally I am most grateful to The History Press for taking a gamble. Biographies of the famous and gifted are common. Books about particular military aircraft, in great depth, including their operational history, are also common. To attempt both at once is not so common.

Glyn Davies, 2014

INTRODUCTION

The names of several Second World War aircraft designers are deservedly well known. R.J. Mitchell (born 1895) is for the Spitfire; Sydney Camm (b. 1893) has the Hurricane; and Roy Chadwick (b. 1893) designed the Lancaster. The name of ‘Teddy’ Petter (b. 1908) has become almost unknown, and yet his aircraft are nowadays legendary, such as the Lysander, Canberra, and Gnat. Additionally, Petter designed these aircraft at three different companies, Westland, English Electric, and Folland. Another unique feature of these aircraft was their radical nature; nothing like them has been designed before or after.

The story of this designer is of a rare individual with singular talents, and an inability to suffer fools and poor management. He was supportive of his good engineering teams, but his intolerance of a hostile management led to his resignation from three manufacturers, even though he was Managing Director of his last company, Folland.

This biography tries to capture the mercurial nature of a basically shy character, and also the radical nature of his designs. These are briefly compared with the worldwide aircraft at the time, in terms of their details and performance. This is naturally a technical judgement, backed by illustrations and diagrams, so appendices on aerodynamics and structures are included, should they be needed. It is hoped that this biography will lead to recognition of Teddy Petter amongst the truly great aircraft designers.

1

FOUR GENERATIONS OF PETTER ENGINEERS, 1840–1935

William Edward Willoughby (Teddy) Petter seems to have inherited his flair for engineering design, and spotting an opportunity, from several previous generations of his family, all from the West Country. In the 1840s John Petter (Teddy’s great-grandfather), an ironmonger at Barnstaple, had built up a considerable fortune, enough to buy for his son James Beazley Petter a business, Iron Mongers of Yeovil. James Petter (Teddy’s grandfather) was clearly a competent and energetic businessman, and was soon able to buy outright the Yeovil Foundry and Engineering Works. He invented a high-quality open-fire grate called the Nautilus in several versions ‘for the study, the dining room and the boudoir’.2 His works employed some forty men making castings and repairing agricultural machinery. The Nautilus grates were to become famous after being selected by Queen Victoria for installation in the fireplaces of Balmoral Castle and Osborne House in the Isle of Wight.1 His business did not make James a wealthy man, mostly because he had fifteen children to support, a large family even for the Victorian era. The third and fourth of these children were the twins Percival Waddams and Ernest Willoughby, the latter of whom was Teddy Petter’s father.

We have a clear account of Percival’s life written by himself,2 and it is obvious that this large family was brought up with strict Christian beliefs. His daughter has said that Percival’s faith enabled him to accept the early death of his two sons.2 At the age of only 20 Percival took over as manager of the engineering works in 1893. He had inherited the inventive streak and, together with B.J. Jacobs, the foreman of the foundry, he designed and built in 1894 ‘the Yeovil Engine’, a high-speed steam engine. More importantly, a year later he designed and built a small 2.5hp oil engine for agricultural use. It was immediately successful and the business expanded so swiftly that by 1904 over a thousand engines had been sold, ranging from 1hp to 30hp in size.

Teddy’s father, Ernest, seemed to think that his own talents were in enterprise and business, rather than sharing his brother’s engineering skills. He worked hard at becoming part of the establishment, and spent more time in London than Yeovil. In fact by 1924 he had stood for Parliament twice (unsuccessfully) and had become chairman of the British Engineers Association. He was given the task of organising the engineering section of the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley, for which the king conferred upon him a knighthood in 1925.

By 1901 the business was growing so rapidly that James Petter could not cope and eventually had a nervous breakdown. Ernest consequently joined his brother and together they bought the business off their father. With much effort they succeeded in raising £3,850 from friends and investors. They made Jacobs the chief engineer, a position he held until his death in 1936. By 1908 the sale of their engines had increased, with a very large number of orders from Russia, where they preferred a two-stroke engine to the older four-stroke versions. In 1911 the company was awarded the grand prix at the Milan International Exhibition for their machines, which now ranged from 70 to 200hp By now the Nautilus works employed 500 people and some 1,500 engines were produced annually. A new foundry was needed and built, completed in 1913, at which point it was one of the largest in Britain. Harald Penrose (who became their first test pilot) later recalled that Percival Petter, his wife and two daughters were present when the first turfs for the new foundry were cut at a site west of Yeovil. Mrs Petter consequently chose the name ‘Westland’ for the proposed factory and planned garden village.

The Petter twins, Percival and Ernest. Teddy’s father Sir Ernest is seated on the right.

In 1915 Lloyd George made a speech in Parliament in which he frankly exposed the inadequacy and unsuitability of the munitions available for continuing the war. A board meeting of Petters Ltd passed a resolution placing at the disposal of the government the whole of the new factory to make anything the government might call for. The War Office did not respond immediately, but the Admiralty asked for a conference, so Ernest and Percival went to London to meet five gentlemen, three of whom were Lords of the Admiralty, who stated that the great need of the Navy was for seaplanes, and they asked whether Westland were willing to make them.

The brothers explained that their ‘experience and the factory were not exactly in line with these requirements but we were willing to attempt anything which would help the country’. The sea lords replied, ‘Good. You are the fellows we want: we will send you the drawings and give you all the help we can. Get on with it.’ Percy recalled that they sent representatives to Short Brothers at Rochester, Kent, to find out what was expected.2 ‘I must confess that my heart nearly failed me when I saw the nature of the project.’ However, he then remembered a Robert Arthur Bruce, whom he had interviewed a year earlier, and who was then manager of the British and Colonial Aeroplane Company at Bristol. He was now the resident Admiralty inspector to the Sopwith Aviation Company at Kingston-upon-Thames. The Admiralty agreed to release him to knock the new factory into shape and realise the output of this manufacturing centre at Yeovil. The work considered for this new project needed a separate title from that of the established oil engine manufacturing company. Hence, although wholly owned by Petters Ltd, it would be operated as a self-supporting Westland Aircraft works, and Ernest Petter would be chairman. The split between the brothers was now official. Percival, the engineer, would look after the Petter engines and Ernest, the businessman, would guide Westland Aircraft Ltd.

One of the very first acts of this company was to recruit a young man named Arthur Davenport, who was appointed as chief draughtsman, and charged with a stay at Short Brothers. There he made necessary production drawings of the Short 184 seaplanes, for which an order for twelve had been placed. The fourth aircraft to be built at Yeovil saw action during the Battle of Jutland, operating from the seaplane carrier Engadine. It successfully reported by radio the movements of German fleet and consequently gave much confidence to the workforce at Yeovil that they were capable of building aircraft as good as those from any other source. Robert Bruce had proved to be a giant in capability, creating a large significant aircraft works from the small shops he had inherited. During the war he was instrumental in seeing over 1,000 biplanes built at Yeovil. They included sub-contracts for Sopwith landplanes, de Havilland DH4 Bombers and the DH9 two-seater bomber. For his wartime work Bruce was awarded the OBE.

After the war the aircraft manufacturers knew there would be no market for military aircraft, but assumed that civil aircraft would no longer be the toys of the wealthy sportsman. However, the public was not in the least air-minded and over a decade would pass before a market emerged, in spite of the Department of Civil Aviation funding competitions for small and large aircraft and seaplanes. Westland had no crystal ball, so in 1922, when the Air Council announced a light aircraft competition, Robert Bruce submitted a biplane and Arthur Davenport a monoplane. Both prototypes were built and flew in 1924. Thirty of the (Widgeon) monoplanes were eventually built but production ceased in 1929.

The depression years were a lean time for speculation but Westland kept going by re-engineering the DH9 biplane with a new fuselage and a Bristol Jupiter radial engine. This aircraft, named the Wapiti, was a commercial success and eventually more than 500 were built and used by the RAF in the north-west frontier of India and in the deserts of Iraq. The company then proceeded with a private venture, which started life as a Wapiti mark V, with a supercharged Bristol Pegasus engine. It became the first aircraft to fly over the peak of Mount Everest in April 1933. This conversion received several contracts with the Air Ministry and more than 170 were built by 1936. However, in 1934 a sea change rocked the company, which had hitherto enjoyed a period of stability with Robert Bruce as managing director and Arthur Davenport as chief designer. This change was forced upon the company by the chairman, Sir Ernest Petter.

The strutted monoplane the Widgeon, designed by the chief designer, Arthur Davenport, in 1923.

Ernest Petter was a strong-willed, domineering father who had ambitions for his bright son, Teddy. However, Teddy saw more of his mother than of his father, since Ernest spent so much time in London, and from her he inherited a strong religious conviction and a set of firm ethical principles, which played a major part in his upbringing. He was reticent and scholarly, and looked it. His appearance was to influence his relationships throughout his business and family life.3 He might have looked a scholar and introvert, but he turned out to be supremely confident in his own abilities, almost arrogant, and was to have many conflicts with government officials and captains of industry, who might have thought he was a pushover.

Teddy was sent away to prep school until he was 12, when his father decided he should go to Marlborough public school. According to Teddy’s brother Gordon, his father probably picked this prestigious public school as a reaction to his own lack of higher education, and to ensure that his eldest son had the best possible preparation for taking over the family business.3 Ernest also wanted Teddy to become proficient in such sports as rugby and cricket. Teddy’s first house master was a double blue and expected all of his pupils to demonstrate a similar prowess. Although Teddy proved to be an outstanding scholar, he did not enjoy any of the sports, having neither the requisite physique nor inclination. He is said to have preferred to spend time on intellectual pursuits, and was especially interested in the great philosophers Kant and Nietsche.3 For relaxation he read motor car magazines and took solitary walks in the Wiltshire countryside. His time at Marlborough did much to develop his aloof and withdrawn attitude as a defence against the many snubs he must have endured by not being one of the sporting set.

The young Teddy Petter, possibly taken at Marlborough College or at Cambridge.

He left school for Gonville and Caius College at Cambridge, where he read engineering. In the final year of the Mechanical Tripos he was awarded a first-class honours and a gold medal in aerodynamics. He led a reclusive life at college, but had one friend, John McCowan, who had rooms on the same staircase. They shared a passion for motor cars and acquired an old air-cooled sports car, in which they travelled to the McCowan’s farm in Yorkshire. It was at this farm that Teddy met an attractive French girl, Claude Marguerite Juliette Munier, the daughter of a Swiss official at the League of Nations in Geneva. She was to become his beloved wife, although his engagement was not welcomed by his parents, who were prejudiced against ‘foreigners’ and compared her unfavourably with the daughter from a well-heeled English family with whom his brother Gordon was seeking an engagement at the time. Gordon is on record as attributing his brother’s puritan strain to their mother and her Huguenot ancestors.

On graduating in 1929 Teddy agreed to his father’s suggestion that he join Westland as a ‘graduate apprentice’. He then served the statutory two years moving from workshop to workshop, and is believed to have insisted on no special favours as the chairman’s son. The chief test pilot, Lois Paget, said ‘I can’t stand that priggish young man.’ In fact in later years Teddy was to say: ‘I looked on this as sheer drudgery at the time, but knew afterwards that without workshop knowledge I would never have become a designer.’3 In the spring of 1932, Sir Ernest appointed Teddy, at the age of 23, as personal assistant to the managing director, Robert Bruce, who perhaps understandably did not welcome this appointment and ignored his presence in his office. Teddy consequently spent much of his time with John McCowan modifying an Austin 7 to win several sporting trophies. Despite this enthusiasm for sports cars, he never wished to learn to fly. The Westland chief test pilot, Harald Penrose, tried to get him interested but reported ‘his sole attempt at piloting revealed a lack of the required sensitivity coupled with hopeless judgement of speed and distance, so his efforts at approaching for a landing were abysmal’.4

Whilst serving his time as personal assistant, Teddy set the date for his marriage to Claude: August 1933 in her home town, near Geneva. John McCowan was best man, and Sir Ernest and Lady Petter attended somewhat grudgingly. Teddy’s two daughters, Camile and Françoise, were born whilst he was serving out his assistantship with Bruce, whose retirement was due in late 1934.

It seems that Bruce had an inkling that Sir Ernest would appoint Teddy as his successor, so in May 1934 he announced his resignation, to take effect within a month, whereupon Ernest announced that Teddy had been co-opted to the board and would be in charge of all design activities. Ernest later entitled Teddy to assume the title of technical director. This looked like a deliberate snub to the chief designer, Arthur Davenport, and Bruce’s son-in-law, Stuart Keep. Bruce insisted that Keep, at least, should also be appointed to the board, and when this was refused tendered his resignation to take effect immediately. Teddy became technical director at the age of 26, with the more experienced Davenport (aged 43) reporting to him, whilst Keep was made works manager. For several years the Air Ministry left Westland off their list of potential bidders for military aircraft because Petter was not considered a sufficiently experienced or dependable designer.

In fact Teddy had learned a great deal from Bruce in three years, especially his means of keeping tight control on design development by spending time at the boards of all of his draughtsmen and at the desks of his aerodynamicists and stressmen. Petter was not alone in this practice apparently as others such as Sydney Camm at Hawker and R.J. Mitchell at Supermarine operated similarly. Petter adopted this practice throughout his career and consequently was never hit by unexpected surprises. He was able to make informed decisions on who deserved promotion and who did not. One of his first important decisions was to scrap the Pterodactyl, a grotesque aircraft, which was essentially a flying swept-back wing and needed no tailplane or fin.

This was not a good time to expect profitable contracts for military aircraft. Sir Ernest gave a lecture to the Royal Aeronautical Society in Yeovil in which he emphasised the need to remove barriers leading to delays and heavy costs in the development of new aircraft. He asked for encouragement similar to that enjoyed by manufacturers on the Continent and elsewhere. Teddy was not, apparently, helped by his aloof attitude towards the Air Ministry officials, who found him supercilious and overbearing. Consequently, as no military aircraft contract looked to be forthcoming, Petter persuaded his father to put up company capital to pursue a private venture, a high-wing three-engined six-seater to compete with the De Havilland Dragon/Rapide.

From left to right: Arthur Davenport, Harald Penrose, test pilot, and Robert Bruce.

Unfortunately Ray Chadwick at Avros had already proceeded with such a design and had interested Imperial Airways and the Air Ministry. So, in his first year as technical director, Petter tried his hand at a wide range of aircraft designs, all without success. However, the Widgeon, designed by Davenport ten years earlier as a high-wing strutted monoplane, was going through several development cycles and it allowed Petter to start his career as a designer. In particular his new design, called the P7 (P for Petter?), exploited an adventurous Handley Page device for high lift, namely a wing leading edge slat which automatically deployed as the wing incidence was increased and the leading edge pressure intensified (see Appendix 1). The movement of these slats was also geared to the trailing edge flaps.

Westlands showed that this system was highly effective and mechanically reliable. This established Petter’s reputation as a successful designer. In 1935 the army co-operation squadrons were looking for a replacement for their Hawker Audax, and the Air Ministry included Westlands on its list of bidders for a military aircraft designed to have a very low stalling speed. Petter’s response was the P8, later to be named the Lysander. Hawkers had submitted their own replacement design and were awarded a contract for 178 Hectors, which was passed on to Westland as a subcontractor: a blessing for Westland and Petter in particular. Westland were now building the Hector and the Lysander. (It is tempting to speculate whether the name Lysander, to join Hector, was the choice of the scholar Teddy Petter.) The Lysander’s time was still to come, and it would eventually replace the Hawker aircraft in the RAF squadrons.

2

THE WESTLAND YEARS: THE LYSANDER, 1935–1944

On 16 July 1935 came the first of several events that would nearly break up the Petter family. At this time, Teddy was 27 and had been technical director for less than one year. Sir Ernest Petter had become the Westland chairman, and his replacement as managing director was Peter Acland, who had been in charge of the London office. Acland went on to play a major role in supervising production with Teddy’s help, thereby undercutting the general manager, Stuart Keep, who finally felt forced to resign. Westland needed more new workshops so Sir Ernest decided to look for expansion opportunities. He convened a shareholders’ meeting to vote an increase in Westland’s capital to £750,000 by creating more shares to provide funds for a merger with British Marine Aircraft, who had large workshops at Hamble, on Southampton Water. Teddy and Acland threatened to resign, so he decided not to proceed with the merger.

This conflict between Teddy and Sir Ernest would take a long time to heal. Teddy still had a scholarly, almost reserved appearance, a feature which emphasised his reputation for arrogance. He did, however, have a stubborn streak, as was to become evident in future conflicts with those who did not share his views. In the present case the conflict was with his father. The rift was to become even greater in 1938, when Sir Ernest negotiated a deal with John Brown shipbuilders to buy a controlling interest in Westland Aircraft. In the meantime Teddy was to take his P8 design as a successful bidder for the Air Ministry’s new military specification, A39/74.

The specific requirement for ‘The Army Co-operation Aircraft’ seems a rather curious one today. Its roles included general liaison duties (such as the transport of executive officers), limited bombing, message pick-up (scooping bags on ground), reconnaissance and spotting enemy artillery. However, in the 1930s all nations agreed on the need for rapid and efficient communication between senior military staff, especially as an army was advancing over a wide front. Today communication is very sophisticated: think of wars undertaken under the auspices of the United Nations, when more than a dozen nationalities, speaking several languages, have to fight a common enemy and not each other. This was not the case in the 1930s. Semaphore was still a conversational tool (and still is in the NATO navies). The design of an aircraft in this ‘army co-operation’ role, foreseeing a European war in the offing, was undertaken by several nations: Germany, France and Poland. Four are worth mentioning.

The earliest design was the French Brequet 270 in 1928. It was a biplane produced for the Armée de l’Air and had a high drag, which resulted in a maximum speed of only 147mph. Its range was 620 miles, a value considered desirable. A total of 100 were delivered to the armed forces in 1930 and 1932.