56,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

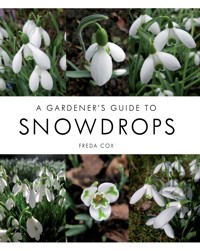

Snowdrops are one of the best loved, most popular and widely grown of all bulbous plants. This book celebrates their beauty and magical annual resurrection. This newly updated and expanded edition of this best-selling book introduces the twenty known species and has been updated to cover more than 2,400 named snowdrops. Discover the vast range of shapes, sizes and markings of these beautiful flowers. With information on cultivation and planting, detailed descriptions, informative drawings and interesting anecdotes this will be an invaluable companion for all gardeners, and will inform and delight both the aspiring and seasoned galanthophile. A comprehensive directory of names, descriptions and illustrations of hundreds of beautiful snowdrops. Beautifully illustrated with 86 plus a directory of 2002 colour illustrations. Freda Cox is a writer, established botanical artist and committed galanthophile.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 803

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

A GARDENER’S GUIDE TO

SNOWDROPS

FREDA COX

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2019 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2019

© Freda Cox 2019

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author's and publisher's rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 450 6

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Preface

PART 1

1 The Snowdrop

2 Morphology

3 Taxonomy

4 Snowdrops Around the World

5 Pests and Diseases

6 Galanthophiles, Gardens and Growers

PART 2

7 Snowdrop Species

8 Snowdrop Directory

Glossary of Terms

Bibliography

Useful Addresses

Index

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks must go to the many people, too numerous to mention, who helped with information and photographs including Jim Almond; John Amand; Paul Barney; Jože Bavcon; Michael and Anne Broadhurst; Andy Byfield; Ian Christie; Sir Henry and Lady Elwes; Hagen Engelmann; Sir Peter and Lady Erskine; Rik Goodenough; Freddy van Houtte; Melvyn Jope; Cyril Lafong; Ruslan Mishustin; Gerard Oud; Calvor Palmateer; Harry Pierik; Angelina Petrisevac; Mark Smyth; Eddie Tijtgat; Petra Wagner; Carolyn Walker; Anne Wright; and all the other breeders and Galanthophiles, with a special thank you to Thomas Seiler for his support, and Werner Reinermann for providing so many beautiful photographs of new Galanthus. Also to garden owners for their photographs.

A big thank you to my young granddaughter Mia Hawthorne (11) for her expert secretarial help with cross-referencing, and all the rest of my family and my many friends for their patience and understanding with all my moans, groans and complaints about numerous problems. I appreciate you all and your help and support are invaluable.

Dedication

I owe a great debt of gratitude to Ian and Ingrid Jacobsen, whose advice, support, help and encouragement provided the impetus to persevere with this new edition. A big welcome to Elsie-Mae Hawthorne who has joined my family since the first edition of this book was published. A future Galanthophile perhaps?

PREFACE

When I wrote A Gardener’s Guide to Snowdrops in 2012–13, there were around 1,500 named snowdrops. Today there are over a phenomenal 2,500. In this updated edition I have included descriptions of almost 2,500 named snowdrops, with drawings of over 2,000. Some small nuance in the shape of the flower or marking heralds a new name as keen Galanthophiles from different countries search out and introduce new flowers virtually every day.

Despite many hours spent researching and drawing as many named snowdrops as possible, I still find the little white flowers quite magical – although I have to admit there have been times when I wished not quite so many had been named.

I still think nothing compares to the excitement and anticipation of seeing those very first snowdrops emerging through the frozen earth, or great swathes of white naturalized around the countryside in the depth of winter. We already have heavily green-marked and yellow-marked snowdrops, but give me the tiny common G. nivalis any day. I don’t want orange or pink snowdrops. Coloured flowers could never be worthy of the name, so would we then have to call them sugar plum fairy pinkdrops or orangedrips? What would spring be without the tiny white flowers heralding the New Year in all their simple purity and beauty? It wouldn’t be quite the same if these flowers were pink or orange. However, this will not stop eagle-eyed Galanthophiles searching for new variations and new names and this extensive list will continue to grow through the coming years – as will the astronomical prices some of these new snowdrops achieve.

Snowdropomania continues apace with autumn-flowering species now very much in evidence in many gardens, extending the season even further. We can have snowdrops in flower for over eight months of every year if we so desire.

Snowdrops have become a massive success story and one set to continue for many years to come. It will hopefully not end in the same disastrous way that Tulipomania did in the seventeenth century. The intrinsic value of this beautiful flower is in its simple beauty, and the ease with which the flowers can spread into vast colonies. Could we really ask for anything more beautiful?

PART 1

CHAPTER 1

THE SNOWDROP

The humble snowdrop: such a pure and simple flower, but what elegant beauty. Each one brightens the gloom of a winter’s day and nothing is guaranteed to lift one’s spirits more than seeing the very first snowdrops appear each year. Small, undemanding and delicate-looking, they never fail to produce stunning displays, naturalizing in their millions through woodland, fields, lanes and gardens, brightening borders and spilling through hedges onto wayside verges. Within days of the first buds opening, carpets of ice-white flowers spread in great drifts beneath gaunt winter trees.

Snowdrops are heralds of new life and rebirth, appearing as the year’s cycle begins anew, marking the gentle waking of the garden from its deep winter sleep. Spring is coming! Great excitement and eager anticipation greet the arrival of snowdrops each year and snowdrop lovers, ‘Galanthophiles’, wait expectantly for the first tiny shoots to pierce the ground – two grey-green leaves enclosing a small white bud, opening into a pendent flower.

Snowdrops are one of our best-loved and most recognized bulbous plants. These delicate but extraordinarily tenacious little flowers miraculously appear each year as if by magic, their strong protective sheaths forcing through unyielding, frozen earth. A delicate hint of honey perfume is borne on the breeze in winter sunshine, while the flower provides much needed nectar for early insects, which in turn aids pollination.

Drifts of naturalized snowdrops at Painswick Rococo Garden, Gloucestershire.

Snowdrops naturalized along the banks of the Cound Brook, Shropshire.

Snowdrops mainly flower between mid-January and mid-March although certain species flower as early as September, with others continuing into April. This creates a snowdrop season that can extend up to eight months each year.

At the time of writing there are twenty known snowdrop species with a possible new species to be confirmed in the not-too-distant future. There are around 2,500 different hybrids and cultivars, although this number continues to rise as snowdrop enthusiasts hunt out different variations, adding new names to an already extensive list.

Galanthophiles and Snowdropomania

The record-breaking ‘Elizabeth Harrison’, a single bulb of which sold for £725 on the eBay auction site in February 2012. (Photo courtesy Ian Christie)

The renowned horticulturist E.A. Bowles is credited with introducing the term ‘Galanthophile’ in the 1900s. More precisely he termed the new generation of snowdrop enthusiasts ‘Neo-Galanthophiles’, and applied the word ‘Galanthophile’ to nineteenth-century collectors. However, the attraction in Bowles’ time was very low-key compared to the snowdrop frenzy and crazy prices paid for bulbs today. Seventeenth-century ‘Tulipomania’ seems to have hit the snowdrop world. Then a ‘Semper Augustus’ Tulip sold for 6,000 florins, equivalent today to around £750,000. Now a single, tiny snowdrop bulb can sell for many hundreds of pounds.

In February 2012 one bulb of the yellow-marked G. woronowii ‘Elizabeth Harrison’ set a new record selling for the astronomical price of £725. This broke previous records of £357 for G. ‘E.A. Bowles’ in January 2011, and £360 for G. ‘Green Tear’ in March 2011. It appears new records are created every year, right up to an incredible £1,390 paid by someone in a competition to have a snowdrop named for them. Many of the more sought after snowdrops regularly sell for between £50 and £100 each, but thankfully common G. nivalis are still relatively inexpensive to buy and quickly spread into impressive colonies.

Snowdrop aficionados or Galanthophiles regularly travel hundreds of miles, even visiting different continents to see specific plants, collections, gardens, and attend talks and events. Despite freezing temperatures, torrential rain and often heavy snow they can be seen crawling about on hands and knees or even lying flat in the mud to examine a particular snowdrop’s markings more closely.

It is a sad and damning reflection that a few fanatical and unscrupulous collectors are not immune to stealing. A number of gardens have reported thefts of rare snowdrops by people who obviously knew exactly what they were looking for. Many gardens now remain closed, sadly denying genuinely honest and interested people the chance to see spectacular displays. Most collections now have stringent security measures in place.

Naming the Snowdrop

The derivation of the name ‘Snowdrop’ may never be known. Closest is the Swedish ‘Snödroppe’, but some say it comes from the German ‘Schneetropfen’, a popular style of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century drop earring. The German ‘Schneeglöckchen’ and Dutch ‘Sneeuwklokjes’ refer to snow-bells.

Other names include ‘Fair Maids of February’, ‘Candlemas Bells’, ‘Dingle Dangles’, ‘Eve’s Comforters’, ‘Snowflowers’ and ‘White Ladies’. In France they are ‘Galantine d’hivre’ or ‘Pierceneige’; in Italy, ‘Bucaneve’; and in Hungary ‘Hóvirág’.

Galanthus comes from the Greek ‘gala’ (milk) and ‘anthos’ (flower), while ‘nivalis’ means ‘of the snow’.

Legend and Superstition

Many superstitions and legends surround snowdrops. It was either lucky or unlucky to take the flowers indoors and could herald a death. In some areas taking the first snowdrop into the house was unlucky but after that all would be well.

The name ‘Eve’s Comforters’ is said to have arisen when Eve was weeping in Eden as no flowers grew in winter. An Angel breathed onto a passing snowflake and snowdrops sprang up everywhere. The Victorians associated snowdrops with death, saying ‘they grew closer to the dead than the living’, and they resembled shrouds or a corpse in its shroud. The herb ‘Moly’ is referred to in Homer’s Odyssey and in 1983 Duvoisin suggested this was the snowdrop.

Greek legend tells that the earth turned to winter when Persephone was taken to the Underworld. Snowdrops were one of the plants she brought back on her return but as the flowers came from the Underworld many considered them unlucky.

According to German legend, the snow asked God for a colour and he told it to ask the plants and animals for one of their names. The snowdrop was the only one willing to share its name and so snow became white.

Garden folklore tells that before moving snowdrops one should always tell them what is happening otherwise they won’t thrive afterwards.

Snowdrops traditionally signify hope and virginity. In Victorian times young maidens carried snowdrops as a sign of purity, while if a gentleman was given a few of the flowers it was a sign his advances were too ardent.

Medicinal Properties

There are no records showing when snowdrops were first used medicinally. Herbal remedies were widely used throughout the ancient world. The ancient Druids were highly skilled in using herbs for healing and looked upon snowdrops as potent heralds of their spring festival, Imbolc.

The whole of the snowdrop plant is toxic and the bulbs particularly so. If ingested they cause stomach cramps, diarrhoea, dizziness, nausea and vomiting. Although there have been instances of this causing death, most people recover.

At one time rubbing snowdrop leaves on the forehead was said to relieve headaches and there are reports from Russia that a decoction of the bulbs was beneficial in treating poliomyelitis. G. nivalis is reputed to be an emmenagogue, stimulating the menstrual flow, possibly resulting in abortion in the early stages of pregnancy.

It is important to note that any natural or herbal treatments should only be used under the strict supervision of a qualified practitioner.

Snowdrop leaves and bulbs contain the active substance Galanthamine, used in a group of anticholinesterase drugs. Galanthamine was originally obtained from wild snowdrops, in particular G. woronowii, in the Balkans.

In the 1950s scientists began extracting Galanthamine from G. nivalis, giving rise to the drug ‘Nivalin’. Galanthamine has important properties that aid treatment and management of Alzheimer’s, poliomyelitis, severe injuries to the nervous system, and nerve associated pain. Expensive synthetic processes were introduced but then withdrawn from patients in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease due to cost.

Naturalized Galanthus nivalis, Cound Brook, Shropshire.

Galanthamine also occurs naturally in Narcissus species and research is ongoing regarding the viability of producing reliable supplies from this source as well. If successful it could drastically reduce the cost of such drugs. Snowdrops also contain the glycoside scillaine (scillitoxin), and another alkaloid, narcissine (lycorine).

The mannose-binding specific lectin in G. nivalis – agglutinin, or GNA, is used in medicine, bacteriology and agricultural biotechnology research. Being toxic to certain insect pests it creates effective insecticides. The gene was cloned in 1991 and has been modified and transferred to a number of crops including wheat and rice. Research continues into establishing the potential for further insect-resistant genes that can be introduced into plants to make them increasingly pest resistant. Research is also under way to establish whether the snowdrop lectin GNA can be beneficial in treating HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus).

A Brief History

It is uncertain when snowdrops were first recorded. There is a possible reference to the snowdrop as ‘Leukoion’ by Theophrastus (372–287 BC) although this is not conclusive, as the name was also applied to other plants. An old glossary of 1465 is considered to refer to the snowdrop as ‘Leucis i viola alba’ – the white violet.

Records show that snowdrops were cultivated in Britain in the 1500s. John Gerard (1545–1611/12) referred to them as ‘The timely flow’ring bulbous violet’ and the original 1597 edition of his Herball includes an unmistakable drawing and description of the snowdrop.

Other old manuscripts listing snowdrops include Commentarii in Sex Libros Pedacii Dioscoridis (1544) by Pietro Andrea Mattioli (1501–77), although here the snowdrop is depicted with numerous leaves. Carolus Clusius (1526–1609) refers to the fragrance of a G. plicatus received from Constantinople, also known as ‘Clusius’s Snowdrop’.

The name ‘snowdrop’ appears for the first time in 1633 in Thomas Johnson’s revised edition of Gerard’s Herball, with a footnote for ‘timely flow’ring bulbous violet’ – ‘Some call them also snowdrops’, including an unmistakable drawing.

There are numerous other references including Sir John Evelyn (1620–1706) in his Kalendar of Horticulture, 1664; Robert Furber (1674–1756) in the Flower Garden Display’d, 1732, refers to the ‘Greater Early and Single Snowdrop’, and does so again in 1733, in A Short Introduction to Gardening; or, A Guide to Gentlemen and Ladies in Furnishing their Gardens. The plant finally received its generic name, Galanthus, with the species epithet nivalis from Linnaeus in his 1753 Species Plantarum.

It is most likely naturalized colonies of snowdrops evolved from garden escapes. ‘Wild’ snowdrops were recorded by William Hudson (1734–93), the English botanist, in his 1778 Flora Anglica, as growing in meadows, hedges and orchards. William Withering (1741–99) noted snowdrops in Gloucestershire and Worcestershire. Sir James Edward Smith (1759–1828) listed a number of sites for snowdrops in his extensive 1804 Flora Britannica; in 1841, Jane Loudon (1807–58) published The Ladies’ Flower-Garden, listing two species of snowdrop, G. nivalis, which she considered to be an English native, and the ‘Folded’ or Russian snowdrop, G. plicatus, which she stated was first brought to England in 1592.

G. nivalis ‘Flore Pleno’, the double snowdrop, appeared in 1703 although its origins are obscure. Nineteenth- and twentieth-century plant hunters introduced new species and varieties, while travellers brought bulbs home with them. G. plicatus for example, was brought back to Britain by soldiers returning from the Crimea.

In 1879 the Gardener’s Chronicle recorded nine types of G. nivalis, together with G. elwesii, G. plicatus and G. reginae-olgae.

The first accurate classification was by Swiss botanist Pierre Edmund Boissier (1810–85) in his 1882 Flora Orientalis. He included G. nivalis, G. graecus, G. reginae-olgae, G. elwesii, G. plicatus and G. latifolius. By 1894 Günther Beck (1856–1931) was listing thirty-five Galanthus, while Paul von Gottlieb-Tannenheim in 1904 noted three species and eight subspecies.

With numerous hybrids and new cultivars being introduced and snowdrops becoming increasingly popular, the Royal Horticultural Society held its inaugural Snowdrop Conference in 1891. James Allen (1832–1906) was a speaker. He was an amateur horticulturist who grew more than one hundred varieties and possessed the largest collection of snowdrops in England at the time.

Edward Augustus Bowles (1865–1954), a self-taught horticulturist and botanical artist, wrote about snowdrops in 1914 and 1918, and contributed to the important 1956 monograph Snowdrops and Snowflakes by Sir Frederick Stern (1884–1967).

Otto Schwarz (1900–83) wrote a treatise on snowdrops in 1963, grouping them by leaf colour, and in 1965 Zinaida Trofimovna Artjushenko produced an even more detailed account finally listing seventeen species and two subspecies.

More recent publications include Peter Davis’s account of Turkish Galanthus in Flora of Turkey, 1984; Zeybek, who lists twenty-four taxa in his study of Turkish snowdrops, 1988; Aaron Davis, The Genus Galanthus, 1999; Bishop, Davis and Grimshaw’s Snowdrops, 2001; Hanneke van Dijk, Galanthomania, 2011; Schneeglöckchen (2011) by Günter Waldorf; and A Gardener’s Guide to Snowdrops (2013) by the author.

Galanthus nivalis ‘Flore Pleno’.

In Victorian times interest in snowdrops reached feverish proportions before declining. In the last sixty years snowdrops have seen a renaissance. New snowdrops appear almost daily, astronomical prices are achieved and twin scaling and micropropagation increase saleable stocks. It looks as if the trend will continue for many years to come.

General Overview

Snowdrops are bulbous perennial geophytes in the Amaryllidaceae family. They are hermaphrodite, having both male and female organs. Bulbs produce a pair of basal leaves, although occasionally there may be three or more. Leaves are usually present at flowering but sometimes only appear after flowers have faded, especially with autumn species.

There is generally one stem or ‘scape’ to each bulb, but sometimes two and occasionally three. Although the flowers are often said to have ‘petals’, these are in fact ‘tepals’, so named when the perianth cannot be clearly differentiated into a petal or sepal. Botanically the flowers are described as having tepals or segments.

Snowdrops from Walter Nöldner’s Aus Wald und Flur, 1937.

Autumn-flowering Galanthus reginae-olgae. (Photo courtesy Harry Pierik)

Snowdrop flowers are commonly white, solitary, pendent and suspended from a slender pedicel. Three larger outer segments surround three smaller inner segments, which usually have a green mark just above the notch or sinus. The under surface of the inner segments is generally delicately striped green.

Snowdrops vary in height from 5cm (miniatures) up to 30cm+ (giants). Flowers can be single or double, pendent or upright, and vary in shape, size and number of segments. Snowdrops are now being selected with cream colouring or flushed pale orange, and there is even talk of pink snowdrops. Many have heavily green-marked flowers, or additional flowers on the scape.

Inner segments usually have green apical marks but there can also be a mark at the base, or a single mark across the whole segment. Outer segments can also be marked green. Sometimes marks are yellow instead of green. There are pure white albino snowdrops, poculiform snowdrops with all segments roughly of equal length, and inverse poculiform snowdrops where outer segments tend to replicate inner segments.

At present there are twenty known species and around 2,500 different named snowdrops. While many look very similar and often even identical, many do show distinctive differences. Autumn species begin flowering around September and other species and varieties will continue to flower until the following April.

Distribution

In the wild, snowdrops grow naturally throughout a large part of central and southern Europe and western Asia, with the widest diversity of species found in northern Turkey and the Caucasus. They grow in areas showing distinct climate changes with hot summers and cold winters. They dislike very hot, dry conditions and shallow soils, tending to prefer cooler, damper, north-facing situations and sloping sites.

Snowdrops appear to prefer growing above calcareous rocks and limestone although they will happily grow in most fertile soils. They enjoy humus-rich soil with a high proportion of organic matter, and shady, damp conditions, particularly in the growing season. During dormancy bulbs can cope with drier conditions providing the soil does not dry out completely for extended periods.

Their natural habitat is woodland, meadows and rocky crevices from sea level up to around 2,700m. Some are true alpine plants, growing above 2,000m, while many species are found around the 1,000m line.

Snowdrops can stand extremely cold winters and have adapted well to the northern European climate, although they are not found naturally in Scandinavia.

Swathes of G. nivalis spreading beneath spring blossom trees. Kyre Park, Worcestershire.

Identification

As snowdrop species and cultivars are often notoriously difficult to determine, identification can be a minefield, even for the most dedicated Galanthophile.

Many snowdrops have been named but are rarely seen; some disappear after only a few brief months. Galanthophiles often disagree as to what a particular snowdrop is, or what it should look like anyway. A number of the 2,500 currently named snowdrops look extremely similar, and some say they are in fact identical. In some instances descriptions and illustrations vary from nursery to nursery – this all compounds the confusion. Certain snowdrops are considered to be extinct by some experts and no longer available, although some Galanthophiles claim they grow them.

There have been numerous instances where different snowdrops have been given the same name and distributed before the anomaly was realized and one subsequently renamed. Often snowdrops continue to be grown under the two names. For instance: G. ‘Nancy Lindsay’ should now rightly be called G. ‘Sutton Courtenay’ but many people still grow it as G. ‘Nancy Lindsay’.

Then of course there is the big G. ‘Primrose Warburg’ debate. John Grimshaw now states categorically that G.‘Primrose Warburg’ is definitely G. ‘Spindlestone Surprise’, despite some growers still coveting their G. ‘Primrose Warburg’, insisting they are different and superior plants.

Another pitfall is that some years a snowdrop can come up looking distinctly different to how it should. A prime example is the yellow-marked G. ‘Lady Elphinstone’ whose markings can vary between yellow and green depending largely on how the lady chooses to present herself that year, or how she feels after being moved.

Markings on green tipped snowdrops can be variable and often they emerge without green tips for a season, but the following year they are back.

Inner segment markings can also be unpredictable. G. ‘Blanc de Chine’ is an albino snowdrop but some years will show a green spot either side of the sinus. G. ‘Ecusson d’Or’ should have yellow marks on the outer segments but some years these are absent. Yellow snowdrops will show a far stronger yellow colouring in some seasons. Certain snowdrops also take time to settle before producing their true marking, often up to three years.

Experts agree that all Galanthus species can be very variable, whilst one experienced Galanthophile, Martin Baxendale, states:

The history of snowdrops is littered withmisidentification sometimes by even the mostexperienced growers.

Need I say more?

CHAPTER 2

MORPHOLOGY

Bulbs

Snowdrop bulbs are spherical to ovoid with a narrower neck or ‘nose’. The basal plate is a flattened area at the base of the bulb from which roots develop. Bulbs are formed from swollen leaf bases compressed together (termed bulb scales), and these store starch created by photosynthesis in the leaves above. Snowdrop bulbs are covered in a thin, brown, papery outer layer or ‘tunic’, although this can be missing, or only have remnants remaining. The tunic is formed from old shrivelled bulb scales slowly pushed outwards as new scales are formed in the centre.

Secondary shoots grow from bulb scale axils, developing into side bulbs around the basal plate, which then go on to produce new plants. Snowdrops also increase from seed.

After flowers have faded, leaves continue to grow, supplying nutrients back into the bulb. A new shoot quickly develops inside the bulb for the following season and the bulb then remains dormant throughout the summer months. With the approach of cooler autumn temperatures new roots begin to grow. The newly formed shoot and bud are protected by a strong cylindrical sheath, a modified leaf, which splits as the shoot reaches the surface, allowing the bud to emerge.

Each bulb usually produces a pair of leaves, a single flowering stem or scape, and one pendent flower.

Leaves

Although the shape and markings of snowdrop flowers are extremely significant, these can and do vary in the same species. Leaves are an important aid to identification.

Taxonomically the shape of the leaf base is the plant’s most distinctive feature. Snowdrops generally produce a pair of leaves, sometimes three, and certain cultivars even more. There are three distinctive leaf forms denoting different species of snowdrop, G. nivalis, G. plicatus or G. elwesii. This ‘vernation’, referred to as ‘applanate’, ‘explicative’ or ‘supervolute’, is an important feature in helping distinguish between species, and also helps determine parentage of hybrids and cultivars.

• Applanate: two opposite leaf blades pressed flat against each other in the bud and as they emerge.

• Explicative: leaves held flat against each other but with the leaf edges folded back, or sometimes rolled.

• Supervolute: one leaf clasped tightly around the other inside the bud, often remaining so at the point where leaves emerge from the bulb.

Vernation of snowdrop leaves.

As plants mature much of this vernation becomes indistinguishable, requiring careful examination. It is usually, although not always, detectable at soil level. Depending on the snowdrop type, leaves can either be very lax, semi-erect to arching, or erect as they develop, further aiding identification.

Each leaf has a median line that varies from very pronounced to almost indistinguishable. Leaves are generally smooth or slightly grooved or puckered, and vary in colour from light to dark green, blue-grey or glaucous – caused by a thin coating of wax. Leaves are often darker on the upper surface and paler beneath. Leaf tips vary from acute (pointed) to obtuse (rounded). They can be flat or cucullate (slightly hooded). In most snowdrop species leaves are present at flowering. Some species, such as G. reginae-olgae, have only small leaves at flowering, while in others, such as G. peshmenii, leaves usually only develop after flowering. These are generally autumnflowering species.

Leaves continue to develop after flowers have faded, becoming longer, wider and more lax, continuing photosynthesis to supply nutrients back into the bulb. Because of this, snowdrop leaves must be left to die back naturally and should never be removed. The leaves disappear completely within a few weeks of flowers fading.

Variations in snowdrop flower shapes.

Scape

The emerging bud is protected by a strong, almost transparent sheath or ‘spathe’ which splits as the bud breaks the surface of the ground. A single slender stem, the scape, emerges from between a pair of leaves. At the top of the scape the bud is held erect on a slender pedicel. The pedicel can be upright and short, or long and arching. In most snowdrops the bud soon drops into a pendent position. Some snowdrops produce two scapes per bulb.

Inflorescence

This refers to the flowering parts of the plant. Most snowdrop flowers are pendent and made up of six segments arranged in two whorls of three, which are not joined to each other at the base. These are referred to as the inner and outer perianth segments. Each scape generally produces one flower, although more snowdrops are now being developed with two flowers and in rare instances even three. Some flowers have long, slender pointed segments, others are shorter and more rounded resembling a spoon or peardrop shaped flower. Some have very globular flowers with very broad, rounded, ribbed and textured segments. Flowers can have more than six segments, as in G. nivalis ‘Flore Pleno’, the double snowdrop, where inner segments are multiplied to form a ruff. In some areas G. nivalis ‘Flore Pleno’ are more common than the single G. nivalis.

Spiky double snowdrops have very slender segments and often point outwards or upwards from the pedicel. Poculiform snowdrops usually have all six segments of equal length, while in inverse poculiform flowers the outer segments are similar to the inner.

The three larger, equally sized outer perianth segments are convex, spoon or bowl-shaped (cunneate), usually white, and often lightly longitudinally ridged. They taper towards the base, often forming a ‘claw’ where they join the ovary. Very pronounced claws are referred to as ‘unguiculate’. If the claw has slight furrowing this is termed ‘goffering’. Some snowdrops have green marks on the outer segments which can vary from very small to almost covering the whole segment.

Variations in snowdrop inner segment markings.

The outer perianth segments surround three smaller, white, inner perianth segments. They can be rounded or slightly pointed at the apex, with a small notch or sinus. The sinus is present in most, although not all snowdrops. Inner segments are less curved and more tube-like than the outer and generally have green marks above the sinus, although these can be absent. These marks are usually small and take the form of an inverted ‘U’ or ‘V’, heart, or Chinese bridge shaped mark. Depending on the species or variety the mark can be a thin line, a spot either side of the sinus, X-shaped, scissor-shaped, or heart-shaped. There may be two marks, one at the apex and one at the base of the inner segments, or the mark can cover almost the entire segment in which case it often pales or ‘diffuses’ towards the base. The shape and coloration of marks are important in helping identify different snowdrops. The underside of the inner segments is generally ribbed and finely striped green.

Some snowdrops have yellow or apricot coloured markings instead of green, for example G. ‘Wendy’s Gold’. In some snowdrops the colour diffuses across the segments. New snowdrops are being introduced where flowers are tinged cream or orange and even pink.

The temperature inside the inner segments is up to two degrees warmer than the outside air temperature, thus giving a further measure of protection for the delicate reproductive parts of the plant. Snowdrop flowers remain in bloom for a long time compared to many other bulbous plants. Under normal conditions flowers will usually last for a good month or more. The flowers produce a delicate honey perfume as well as providing an important source of nectar for early bees, particularly bumblebees, and snowdrop flowers are specifically adapted for pollination by bees.

Fertilization

The inner segments of the snowdrop surround six stamens that in turn surround the slender, straight style. The filaments are straight and usually shorter than the perianth segments. Stamens are not attached to each other and are only attached to the flower at the receptacle. Orange-yellow anthers open by way of two terminal splits that gradually extend towards the base. Anthers mature at the same time as the stigma and the orange-yellow pollen is released when flowers are moved either by the breeze or by insects. A barely discernible nectary at the base of the style and filaments secretes nectar, attracting insects. Bees coming for the nectar touch the stigma, which is longer than the anthers, with pollen from flowers previously visited, thus effecting pollination. If the flower has not been pollinated by insects the stalks of the anthers loosen and the anthers meet so that pollen falls onto the stigma. As the weather warms, flower segments open wider to allow fertilization, closing again as temperatures cool.

The small swelling at the top of the snowdrop flower is an inferior three-celled ovary made up of three fused carpels. These ripen and split into a three-celled, oval to spherical capsule, formed from the receptacle and ovary. Tiny, oval creamy-white seeds have fleshy tails (elaiosomes), which shrink as seeds mature. After pollination the flower fades and the scape drops into a prostrate position until it touches the ground. The capsule swells until it eventually opens to release seeds that contain substances ants find very attractive, thus helping with distribution.

Propagation

Snowdrops spread quickly from small bulblets that form around the basal plate of the parent bulb, developing into new plants. Most snowdrops also reproduce from seed and can hybridize to form new seedlings that can continue to cross, potentially giving rise to new cultivars.

Some clones are sterile and don’t produce seed while other snowdrops can be extremely prolific. The excitement comes in never quite knowing what will happen until a new flower is produced.

Snowdrops flowering during the main period, mid-January to mid-March, produce ripe seed between late April and June. Germinated seeds develop into a small bulb with a single leaf by the following season. The bulb increases in size, producing two leaves in the second season, followed by a flower in the third or fourth year. Sometimes flowering can take up to six years.

To isolate seed of special snowdrops, a small muslin bag can be placed over the capsule and secured to the scape. Seed can be harvested when ripe, usually when it has turned yellow around mid-May to mid-June. Clean, store and label seed; it will keep for up to a maximum of one year if kept cool and dry. However, best results are obtained by sowing while still fresh.

Seed can be planted into the ground in shallow drills or sown in pots or trays of compost and placed in an open frame. Label and water well but gently. Keep moist but not waterlogged and don’t let pots dry out. Germination takes place in late winter with a small grass-like leaf.

After germination keep seedlings moist, and a monthly application of a weak solution of tomato feed is beneficial. Once leaves have died back re-pot in new sterile compost in the second year. Plant into permanent positions in the third year.

Snowdrops do not need dead heading unless stray seed is likely to come close to established groups of special snowdrops.

Cleaned bulb prepared ready for chipping.

Neck of bulb cut back to top quarter.

Bulb placed cut side down and divided into four parts.

Each bulb quarter is divided again to give eight scale sections.

Each group of scales is further divided again to give sixteen scales.

Scales after between four and twelve weeks showing formation of new bulblets.

Chipping and Twin Scaling

Chipping and twin scaling, particularly of rarer and slow-to-establish snowdrops, can give excellent results and bulk up stock more quickly.

Use healthy, dormant bulbs usually around June. Mix 80ml of water into 1,000ml of vermiculite (enough for about three bulbs). Stir well and set aside. Make a solution of systemic fungicide as directed on the pack. Sterilize all implements with methylated spirits. Take a bulb, carefully remove the tunic, and using a sharp knife or scalpel cut away roots and basal plate until it is level with the first scale layer. Cut back the neck to approximately the top quarter of the bulb, or the neck can be left, as this will often produce small bulblets. Remove any damaged or discoloured patches.

Large swathes of naturalized snowdrops colonize areas of countryside but it is illegal to dig up or remove bulbs without the permission of the landowner.

Holding the basal plate upright, slice the bulb vertically and continue slicing until it is divided into equal sections. Depending on the size of the bulb there can be between two and thirtytwo sections or chips. Each cut section must contain a small portion of the basal plate. Sections should be large enough so that they can be carefully sliced downwards between the scales so each section produces two scales – twin scaling.

Submerge sections in fungicidal solution for half an hour, drain and wash with sterilized water. Blot off excess moisture with kitchen roll and place sections into a clean polythene bag of vermiculite, making sure sections are separated. Label with the snowdrop name, date taken and number of chips. Seal the bag leaving a good pocket of air, and put in a warm dark place, maintaining a temperature of around 20°C.

Check regularly, removing any that show signs of mould. Infected bags should have remaining sections re-soaked in fungicide for 30 minutes before being placed in a new bag with fresh vermiculite.

After approximately four weeks scales begin to splay out and tiny bulblets appear between individual scales. These are generally ready for re-potting after three months. If nothing has appeared after four to six months material can be discarded along with sections which have not produced bulblets. Losses are inevitable but results are usually good, especially as experience grows.

Plant into 7 or 9cm sterilized pots half filled with a fiftyfifty mix of general compost and vermiculite, or seed compost with horticultural grit. Add a thin layer of sand. Insert the basal end of each section into the sand, making sure sections are not touching. Each pot will hold five or six slices. Gently spray with fungicide and top up with compost.

Label, water carefully, place under glass in a shady situation and protect from frost. Pots should not dry out completely although generally require little, if any, further water until growth appears at the commencement of the normal growing season. Leaves may not be apparent until the second season of growth.

Collection of Wild Bulbs

Wild snowdrops have been massively over-collected, decimating native habitats and putting many snowdrops at risk with stocks seriously depleted. In some areas snowdrops are considered to be under threat of extinction. Wild collection is now generally carefully controlled by legislation and snowdrops in certain areas are only collected at specific times allowing for regeneration. Careful monitoring ensures trade is sustainable, and recent years have seen schemes encouraging commercial cultivation of snowdrops.

Cites

In the early 1990s wild collection of snowdrops came under control of CITES – The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. This is an agreement between governments worldwide to help ensure the survival of endangered species. In most countries it is now illegal to collect snowdrops without a CITES permit, whether bulbs, living or dead plants. It allows limited trade in three species, G. nivalis, G. elwesii and G. woronowii from Turkey and Georgia. All snowdrops are listed under CITES Appendix 2.

Wildlife and Countryside Act (1981)

It is illegal to collect any bulbs from the wild in the UK without the landowner’s permission. This is covered by the 1981 Wildlife and Countryside Act in the UK, and in Northern Ireland the 1985 Wildlife (Northern Ireland) Order. Under the 1968 Theft Act it is a serious offence to remove plants from the countryside for commercial purposes without formal authorization. Severe penalties are imposed by the UK National Wild Crime Unit and by the police.

CHAPTER 3

TAXONOMY

Kingdom: Plantae

Class: Angiospermae

Subclass: Mesangiospermae

Superorder: Monocots

Order: Asparagales

Family: Amaryllidaceae

Subfamily: Amaryllidoideae

Genus: Galanthus

All plants belong to the plant kingdom, Plantae, with a specific order of taxonomy descending through Class, Subclass, Superorder, Order, Family, Subfamily, Genus, Species and Subspecies. In the main it is the lower ranks that are of interest to most horticulturists.

Carl Linnaeus (1707–78) was the first botanist to standardize a complicated and unregulated system for naming plants by introducing a binomial, two-part, classification in 1753. The genus name is placed first, grouping plants with a common ancestry, in this case Galanthus.

There can be different species within the genus, each with its own specific type characteristics applying to that particular species. This forms the second part of the name and is usually more descriptive, e.g. Galanthus nivalis (‘of the snow’), G. elwesii (found by Elwes), G. ikariae (the Greek island of Ikaria where it was found), G. gracilis (‘graceful’). Both genus and species names are usually written in italics.

The next rank is subspecies, having similar characteristics to a species but morphological variations that set them apart, such as distinctively shaped marks or flower segments, or different flowering times. Subspecies are denoted by subsp. or ssp. after the species name, e.g. Galanthus elwesii subsp. elwesii.

In nature most snowdrop species grow in their own distinct geographical locations, which rarely overlap. This means subspecies are fairly limited in the wild as two different species rarely get the chance to interbreed.

A variety comes below the species order and is denoted by the abbreviation var. (Latin varietas). Varieties show noticeable differences to one another in some of their characteristics, will hybridize with one another, have usually occurred naturally without man’s intervention, will breed true from seed, and can only be named from wild populations. Varieties are further reduced to subvarieties, or subvar. (Latin subvarietas). Subvarieties are beneath varieties but above forms. Forms (Latin forma) are denoted by the epithet f. Forms show only minor differences in one characteristic, but are still noticeably different from another form.

Different snowdrops tend to be planted in close proximity in gardens, making it easier for hybridization.

G. ‘Welshway’.

G. ‘S. Arnott’.

G. ‘Titania’.

G. nivalis poculiform snowdrop.

G. ‘Gemini’.

G. ‘Lady Scharlock’.

G. ‘Viridapice’.

G. ‘Lapwing’.

G. nivalis Sandersii Group.

G. ‘Robyn Janey’.

G. ‘Heffalump’.

G. ‘Diggory’.

Clones represent a plant or group of plants derived from asexual reproduction or vegetative propagation, which are the genetically identical offspring of a single parent.

Cultivars

Cultivars are plants specifically bred or selected for certain characteristics that retain those characteristics when propagated on. They can be selected from wild populations or arise spontaneously. Increasingly they are the product of man’s intervention with breeding and propagation programmes on cultivated snowdrops. The resulting plant must be distinctive. It should have its own distinguishing characteristics that are different from other named cultivars, and these characteristics must be maintained when repeatedly propagated from generation to generation.

Regular flowers of cultivar G. ‘James Backhouse’ which often exhibits aberrant segments.

Hybrids

Not all snowdrops produce seed but for those that do, hybridizing can give exciting and interesting – although unpredictable – results. Many snowdrop species are inter-fertile, possibly because they originated from a common ancestor. G. nivalis, G. plicatus, G. elwesii and G. gracilis are certainly inter-fertile and many of the other species may also cross.

Hybrids occur when two or three different species of the same genera are crossed sexually, producing a new plant showing a blend of parental characteristics, or with one more pronounced than the other. Hybridization is often carefully engineered to select and enhance specific features of the parent plants. Natural hybrids occur in the wild. Those occurring naturally in cultivation are termed ‘spontaneous’ hybrids, while those created with man’s intervention are known as ‘artificial’ hybrids. Hybrids also occur between subspecies of a species and are known as intra-specific hybrids.

The list of snowdrop hybrids and cultivars is long and perplexing with much misidentification. Many commercially successful new snowdrops are being bred, and often sell for extravagant prices. However, it can take many years to produce a good snowdrop by crossing and re-crossing. It is also important to use a methodical approach and keep accurate records.

When a new hybrid becomes available it is attributed a name. This is not written in italics, begins with a capital letter, and is enclosed within single quotation marks, e.g. Galanthus nivalis ‘Bitton’. If parentage of the plant is unknown, only the genus and cultivar names are used, e.g. Galanthus ‘Atkinsii’.

Plant names regularly change. New research and information leads to plants being re-grouped, placed in a new species or subspecies, or even transferred to a different genus. New names follow and the original and obsolete name then becomes a synonym of the new plant. It is extremely frustrating when a plant name of many years’ standing changes. Confusing as this is, it is generally for the better, ironing out past inconsistencies to further clarify the whole system.

In their natural habitats most snowdrop species grow in precise locations, generally too far apart for hybridization to take place. (This is not the case in gardens where different species often grow in close proximity.) Hybridization in the wild appears rare with snowdrops; to date the only fully recorded wild hybrid is between G. nivalis and G. plicatus subsp. byzantinus, giving rise to G. ×valentinei nothosubsp. sublicatus. Others may include G. nivalis × G. reginae-olgae subsp. vernalis; G. nivalis × G. plicatus; G. plicatus × G. gracilis; and G. gracilis × G. elwesii. None of these has been fully researched and remain as yet unproven amongst wild species.

Galanthus ×valentinei

Syns. G. nivalis ‘Valentine’, G. nivalo-plicatus

‘Valentine’ Denotes all hybrids between G. nivalis and G. plicatus.

Leaves generally slender as in G. nivalis, flat or explicative margins. Sometimes second scape. Outer segments occasional green mark at apex. Inner segments variable marks at apex. This hybrid was known to both Allen and Burbidge under its synonyms. Beck gave it hybrid status under the name × Galanthus valentinei, now G. ×valentinei.

G. ×valentinei nothosubsp. valentinei

Hybrids between G. nivalis and G. plicatus subsp. plicatus

Not so far found in the wild, but common in cultivation giving rise to such well-known snowdrops as G. ‘S. Arnott’ and G. ‘Magnet’. Leaves applanate, matt, grey-green. Inner segments typically single apical mark, occasionally small green mark at base, sometimes spreading across segment. January–March.

G. ×valentinei nothosubsp. subplicatus

Syns. G. nivalis subsp. subplicatus, G. plicatus subsp.subplicatus

Hybrids between G. nivalis and G. plicatus subsp. byzantinus.

Almost identical to G. ×valentinei nothosubsp. valentinei. Very variable, naturally occurring hybrid, Northwestern Turkey, particularly around Istanbul, deciduous woodland, scrub, grass, rocks and near rivers and streams, 30–150m. Spreads by division of bulbs and seed. Shares characteristics of both parents although these can be very variable in different hybrid groups. Leaves applanate to applanate-explicative, matt, grey-green, glaucescent. Inner segments, green inverted ‘U’ or ‘V’ shaped mark above sinus, often one–two small green marks at base, occasionally mark diffusing across segment towards base. Spreads by offsets or seed. Easy. January–March. Occurs in gardens and cultivated since c.1970. Different clones show distinct differences, forming strong, attractive plants, well suited to the UK climate.

G. nivalis × G. elwesii

Leaves supervolute, generally narrower than typical G. elwesii. Inner segment marks tend to be stronger at apex, paler and smaller at base.

G. plicatus × G. gracilis

Leaves often lax, glaucous, revolute or explicative. Outer segments rounded. Inner segments clasping, tube-like, large green mark across segment, often to base, above large, narrow sinus. Often two scapes.

G. elwesii × G. gracilis

Crosses possibly occur in natural populations in Greece but are not common in cultivation. Examples include G. ‘Ruby Baker’ and G. ‘Colesborne’. Plants usually smaller, leaves supervolute, some G. gracilis twisting, inner segments tube-like, large sinus.

G. elwesii × G. rizehensis

Probably the only garden hybrid between this cross to date is G. ‘Early to Rize’. Leaves supervolute, margins subrevolute, paler median line.

Galanthus ×allenii

Probable G. alpinus × G. woronowii discovered by James Allen. Named in 1891 by John G. Baker in honour of James Allen (1830–1906). At the time considered either a species or hybrid, but later classed as hybrid. James Allen grew this, noting it came via an Austrian nursery in 1883 from wild collected bulbs, possibly but not necessarily from the Caucasus. However, it is not definitively known where this hybrid originated and it could be a garden hybrid. Probably G. alpinus × G. woronowii, although true parentage remains unknown. G. ×allenii is unknown, or extremely rare and so far unrecorded in the wild. Widely cultivated, attractive, popular. Leaves supervolute, broad, smooth, matt grey-green glaucescent, central midrib. Inner segments variable green inverted ‘V’ shaped mark above sinus. Slow to bulk up, can suddenly disappear or fail to grow for no apparent reason. Strong bitter almond perfume. February–March.

Galanthus ×hybridus

Syns. G. ×grandiflorus, G. ×maximus

G. elwesii × G. plicatus. Originally known as G. ×grandiflorus, and supposedly hybrid between G. nivalis and G. plicatus. Shows intermediate characteristics between G. elwesii and G. plicatus. Robust plants, large, attractively shaped flowers. Leaves applanate or supervolute, erect, broad, often glaucous, variable explicative margins. Inner segments generally large mark. Often second scape.

Cultivars include G. ‘Merlin’ and G. ‘Robin Hood’.

Additional Hybrids

Possible hybrids have occurred between G. ikariae × G. elwesii; G. elwesii × G. allenii; G. reginae-olgae subsp. vernalis × G. gracilis; G. nivalis × G. woronowii.

Cultivating Snowdrops

In their native habitats snowdrops grow from almost sea level up to 2,800m, naturalizing into vast colonies. They grow in deciduous, evergreen and coniferous woodland, generally toward woodland edges, and in grassland and meadows at higher altitudes.

In the wild they prefer the cool, moist conditions of north-facing slopes, humus-rich soils and areas of high rainfall. Many benefit from snow melt or grow near rivers and streams. Although they enjoy damp ground and most will survive short periods of flooding they will not tolerate ground that is continually waterlogged.

Galanthus reginae-olgae in November in the Taygetos Mountains, Peloponnese, Greece. (Photo courtesy of Wol Staines)

Typical habitat for Galanthus reginae-olgae in the Taygetos Mountains, Peloponnese, Greece. This snowdrop prefers woodland shade on north-facing slopes around 1,000m, and running water. (Photo courtesy of Wol Staines)

Some species such as G. peshmenii and G. cilicicus favour drier conditions and can grow in more arid areas, although snowdrops do not like drought conditions for too long during dormancy. In Mediterranean areas for instance they grow in the cooler mountainous regions rather than lowland areas. Snowdrops can withstand temperatures as low as −20°C but no colder than −30°C.

In cultivation snowdrops tolerate a wide range of conditions and happily grow in many soil types. They prefer deep, rich, moist soil but not wet ground, and good drainage is important. They benefit from moist conditions during the growing period and drier when bulbs are dormant in summer. Neutral to alkaline soils are best but they grow well on chalk and also clay providing it is not too heavy. Although in general snowdrops dislike ground that is too acid, yellow snowdrops often grow better in acid soil.

Many specialist growers supply quality, disease-free snowdrops and recommend planting ‘in the green’, when flowers have faded but leaves are still growing. Recently it has been suggested that better results are achieved by planting fully dormant bulbs when leaves have completely died back.

Dormant bulbs must be firm and not shrivelled or mildewed. As snowdrops dislike being dried out for extended periods, buying pre-packed bulbs can result in poor results and often these snowdrops take time to establish.

Pot-grown snowdrops are readily available and although more expensive have the advantage of less disturbance to the plants. It is also advantageous to see plants in flower so you know they are exactly what they claim to be.

However they are bought, snowdrops should be planted as soon as possible after purchase, 8–10cm deep and 8cm apart. A light application of bonemeal and sharp sand encourages bulbs to establish and an application of leaf mould is also beneficial. Snowdrops can take time to settle after being moved but once established they provide endless years of pleasure. To maintain a good succession plant a few new bulbs each year. Autumnflowering species are not generally as vigorous as spring and require slightly drier conditions and more sunlight.

Specialist collectors often keep snowdrops segregated in pots in plunge beds of sand, or under glass. G. fosteri, G. reginae-olgae, G. peshmenii and G. cilicicus all benefit from being grown under glass.

Snowdrops take time to establish after planting before they give of their best. The Rococo Garden, Painswick, Gloucestershire.

Most gardeners use snowdrops as part of mixed planting schemes where plants enhance and complement one another. They grow well in borders and beneath shrubs where other plants take over as snowdrops die back. In herbaceous borders both plants and snowdrops benefit from being divided every four years. Snowdrops can edge paths, grow beneath specimen trees, brighten alpine beds and create seasonal displays in containers. Rock gardens are ideal when plants require extra drainage. Niches against rocks provide added protection for tender species of snowdrop as well as creating a natural environment, as wild snowdrops often grow between limestone rocks. Rock gardens are also commonly mulched with fine gravel aiding drainage and also giving extra protection against slugs and snails.

Well-constructed plunge bed at Olive Mason’s garden, Worcestershire.

Glass frames in Ray Cobb’s Nottinghamshire garden.

The colourful winter garden at Olive Mason’s garden, Worcestershire.

Snowdrops integrate well with many other plants including the following: winter-flowering iris; Arum italicum; hellebores; purple-black Mondo Grass – Ophiopogon planiscapus ‘Nigrescens’; Cyclamen; smaller Narcissus species; and other winter- and spring-flowering bulbs such as Crocus, Scilla, Eranthis hyemalis, Anemone blanda and fritillaries. Taller snowdrops integrate well with gently moving grasses such as Stipa tenuissima where the grass forms a delicate moving screen revealing glimpses of ghost-white flowers. Snowdrops such as G. ‘Magnet’ have exceptionally long, slender pedicels creating delicate movement.

It is a wise precaution to mark bulbs, especially rarer snowdrops, so they are not inadvertently disturbed or destroyed when digging.

Snowdrops are one of the best plants for naturalizing in open grassland or woodland, grassy banks, slopes and wilder parts of the garden creating good displays in difficult-to-manage areas. Many, such as G. nivalis and G. elwesii, will develop into vast colonies. When plants become too congested they can be thinned out and re-planted, but it is usually many years before this becomes necessary. If re-planting named snowdrops, particularly the more expensive varieties, label them carefully.

When naturalizing dormant bulbs, plant in irregular groups and water well after planting. Spreading compost and sharp sand in the base of the hole gives bulbs a good start. Space bulbs and fill in with compost and soil. With plants keep the ground level as it was before moving, usually denoted by a slightly paler colouring on the shoot. Always let leaves die back naturally to replenish the bulb. Water well after planting or moving. Aquatic lattice pots are also much favoured for planting snowdrops into the ground as it enables pots to be lifted when necessary with minimal disturbance to roots.

Offset removed from parent bulb.

Snowdrops ready for planting.

Naming Snowdrops

It is of paramount importance that a new snowdrop proves its worth before being named. It must be completely new and not one already available under another name. It must be reliable and distinct, continue to come true each year in different situations, and most importantly, it must be different and worthy enough to warrant a name.

The naming of plants is strictly regulated by the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature for Wild Plants and the International Code of Nomenclature for Cultivated Plants, also known as the Cultivated Plant Code. These set out rules, recommendations and guidelines for naming and registering new plants which must be strictly adhered to. The ICNCP has also established a system of recording permanent reference specimens of the plant type. These can either be pressed herbarium specimens or meticulously accurate illustrations.

It is sensible to register newly named snowdrop cultivars with the Royal General Bulb Growers’ Association (KAVB), Hillegom, Netherlands, established in 1860. The Koninkljke Algemeene Vereenniging voor Bloembollencultuur maintains a database register of bulb cultivars that can be accessed via their website.

The ICRA (International Cultivar Registration Authority) was set up in an attempt to regulate and simplify the naming of plant cultivars and prevent the duplicate use of cultivar and group epithets. Data is updated every four years. It is a voluntary international system and registering a cultivar name does not protect that name or infer any legal right. These are dealt with under the National Plant Breeders’ Rights or Plant Patents. ICRA will check the name is not already in use in that specific genera of plants, and that is has not been used previously. It is important that a full description of the plant is submitted with the new name, including the plant’s parentage, etc.

The International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants offers legal protection to plant breeders when introducing and registering new cultivars. The Royal Horticultural Society’s joint Rock Garden Plant Committee makes awards for outstanding plants and will offer advice on new snowdrops.

Any new name must consist of the plant’s scientific botanical Latin name, in this case Galanthus, followed by a unique epithet that is generally a vernacular term enclosed in single quotation marks. Before 1959 Latin names were often also used for cultivar epithets, leading to great confusion when they were misrepresented as botanical names. After 1 January 1959 the particular epithet had to be in a modern language. If the new name complies with all the correct criteria, it then has to be printed in a legitimate, widely available publication before it becomes accepted. If you are sure your new snowdrop fulfils all the correct criteria then, and only then, is the time to think of a name.

There is still much room for improvement in snowdrop naming and listing. This is where establishing and recording details of a basic ‘type’ for each snowdrop, including an illustration, has great advantages for reference. Many old snowdrops have received new names in an effort to increase clarity and conformity among cultivar lists and names.

SNOWDROPS ALL WORTHY OF BEING NAMED

‘S. Arnott’.

‘Augustus’.

‘Brenda Troyle’.

‘Cedric’s Prolific’.

‘Diggory’.

‘Dionysus’.

‘Galatea’.

‘George Elwes’.

‘Hill Poë’.

‘James Backhouse’.

‘Lady Elphinstone’.

‘Little Ben’.

‘Mighty Atom’.

‘Bloomer’.

‘Trym’.

‘Pusey Green Tips’.

‘Silverwells’.

‘Wendy’s Gold’.

CHAPTER 4

SNOWDROPS AROUNDTHE WORLD

Although native to Europe, snowdrops are now successfully grown in many other countries around the world, even though, due to local legislation, they are still difficult to obtain or import in certain areas.

Hardiness Zones

The US Department of Agriculture (USDA) formulated numbered hardiness zones in 1960 in an attempt to standardize information. This system is now widely used across the world. Zones from one to ten denote climatic conditions of geographical areas in which specific plants grow, depending on the plant’s ability to withstand temperatures in that zone. Zones are calculated in degrees Celsius with reference to the average annual minimum temperatures as defined by latitude, altitude and coastal regions. Certain local factors can affect conditions.

Snowdrops grow best in USDA hardiness zones four to seven, but can grow in zones two to nine. Along the Dutch and Belgian coasts the hardiness rating is eight, decreasing to five on the eastern border between Poland and Belarus. Within these zones certain areas such as the Alps and Carpathian mountains may fall to zones three or four due to their high elevations. Again, due to the effects of the Gulf Stream, some areas such as Arctic parts of Scandinavia are higher than expected, not falling below zone three, apart from one small area, Karajok in Norway, which is zone two. There are obviously variations within these zones.

European Hardiness Zones

UK zones are high on the USDA scale, varying between seven and ten due to the moderating effects of the Gulf Stream. Central Europe shows the transition from an oceanic to a continental climate and zones mainly decrease eastwards.