Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Ratgeber

- Sprache: Englisch

• Why are girls self-harming and suffering eating disorders in record numbers? • Why do girls feel they have to be 'little miss perfects' who are never allowed to fail? • Why are girls turning against each other on social media? • What should we tell girls about how to deal with challenges of every day sexism and violent, misogynistic pornography? • How can parents, teachers and grandparents inoculate girls so they can push back against the barrage of unhealthy messages bombarding them about what it means to be female? Whether they are praised for being pretty rather than smart, or accused of being 'bossy' rather than leaders, teaching girls how to be comfortable with themselves has never been more challenging. Laid out in clear simple steps, Girls Uninterrupted shows the practical strategies you need to create a carefree childhood for your daughters and ultimately help build them into the healthy, resilient women they deserve to be.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 401

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

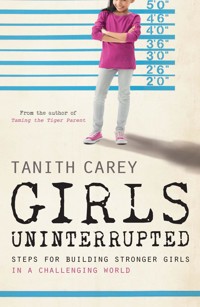

GIRLS

UNINTERRUPTED

GIRLS

UNINTERRUPTED

STEPS FOR BUILDING STRONGER GIRLS IN A CHALLENGING WORLD

TANITH CAREY

Published in the UK in 2015 byIcon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,39–41 North Road, London N7 9DPemail: [email protected]

Sold in the UK, Europe and Asiaby Faber & Faber Ltd, Bloomsbury House,74–77 Great Russell Street,London WC1B 3DA or their agents

Distributed in the UK, Europe and Asiaby TBS Ltd, TBS Distribution Centre, Colchester Road,Frating Green, Colchester CO7 7DW

Distributed in Australia and New Zealandby Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd,PO Box 8500, 83 Alexander Street,Crows Nest, NSW 2065

Distributed in South Africa byJonathan Ball, Office B4, The District,41 Sir Lowry Road, Woodstock 7925

Distributed to the trade in the USAby Consortium Book Sales and Distribution,The Keg House, 34 Thirteenth Avenue NE, Suite 101,Minneapolis, MN 55413-1007

Distributed in India by Penguin Books India,7th Floor, Infinity Tower – C, DLF Cyber City,Gurgaon 122002, Haryana

ISBN: 978-184831-820-5

An earlier edition of this book was published under the titleWhere Has My Little Girl Gone? by Lion Hudson in 2011.

Text copyright © 2015 Tanith Carey

The author has asserted her moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Typeset in Joanna by Marie Doherty

Printed and bound in the UK by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

For my daughters, and yours.

CONTENTS

Introduction

PART ONE

Building a Strong Foundation

Us as parents

The tween years

The role of mothers

The role of fathers

The role of schools

PART TWO

How Building Self-Worth and Communication is Your Daughter’s Best Defence

Self-worth

Connection and creating a sanctuary

Values and boundaries

Emotional intelligence

How to help your daughter find out who she is

How to build communication

What to do if things go wrong

PART THREE

The Influences Around Us

Pornography: Growing up in a pornified society

Pop videos: The pornification of pop

Pretty babies: Make-up and drawing the line between make-up and make believe

Body image: ‘When I grow up I want to be thin’

Branded: Resisting fashion and beauty advertising

Self-harm: How to stop girls becoming their own worst enemies

Connected: Growing up with the internet

Engaged: How to help your daughter use mobile phones safely

Friendships: Best friends or worst enemies

Wired children: Childhood and social networks

Television: Switching off bullying

Fashion: How clothes don’t make the girl

Material girls: How to fight back against the pressure to buy

Toys: Want to play sexy ladies?

Harassment, misogyny and abuse: Keeping girls physically safe

Feminism: Teaching your daughter the F-word

Sources and Research Notes

Further Reading

Acknowledgements

Index

About the Author

Tanith Carey writes books which aim to lucidly set out the more pressing challenges for today’s parents – and set out achievable strategies for how to tackle them. Her previous book, Taming the Tiger Parent: How to Put your Child’s Well-being First in a Competitive World has been called ‘a critique to re-orientate parenting’ by Steve Biddulph. As an award-winning journalist, Tanith writes for a range of publications including the Guardian, the Daily Telegraph, The Sunday Times, the Daily Mail and the Huffington Post. This is her seventh book.

INTRODUCTION

When I chat to my two daughters, thirteen-year-old Lily and ten-year-old Clio, we cover all the usual topics: how their school day went, what’s for dinner, why can’t we get Honey, our dog, to behave.

But throughout the course of our conversations, lots of other, slightly trickier subjects also crop up, like: why is Miley Cyrus naked in her latest video, but for a pair of Dr Martens? ‘I mean, I get why she’s sitting on a wrecking ball,’ Clio has said, ‘because that’s what she’s singing about. But why she doesn’t she have any clothes on?’ From time to time, Lily has also wondered why every year at her primary school fair there is a ‘beauty’ tent for girls to get their nails manicured, when boys never have to bother about how they look.

So was I pleased when, the other day, Clio asked me why Rapunzel just didn’t cut off her own hair and make it into a rope to get down from the tower, instead of waiting for a prince? Am I delighted that Lily’s favourite game as we wait in tube stations is ‘spot the model whose been airbrushed’? Frankly, yes.

Does it make me a humourless, ball-breaking man-hater? Am I brainwashing my poor little girls with politically correct feminist theory? Some people might think that. But I believe I am simply encouraging my girls to open their eyes to a world which might otherwise give them deeply unhelpful messages about who they are, and how they should feel about themselves.

My daughters are not weak and defenceless – and neither are yours. But in a world where many pubescent girls say they are more worried about getting fat than their parents dying or the outbreak of nuclear war, my view is that our daughters need help to work out why so many of their gender think this way – so they don’t end up thinking like that too. They need to know that, in the words of the late Anita Roddick, there are over 3 billion women who don’t look supermodels and eight who do. Because if our daughters are allowed to believe what they see all around them, they will be fooled into believing they have failed before they’ve even begun.

It is the best of times and the worst of times for our daughters. On one hand they have never been healthier, better educated or enjoyed more opportunities in the workplace. When I was born in 1967, women were already making huge strides towards equality. The arrival of the pill meant women finally had a choice about when or whether they wanted to have babies. The stereotypes of females as ditzy airheads, sex objects or housewives whose main job was to serve husbands was starting, finally, to crumble. In their place stood ‘woman’ as she had never been allowed to be: every bit as strong, capable and intelligent as a male. So by rights, my daughter Lily, born 34 years after me in 2001, should be growing up in a world where women are enjoying the benefits of that radical shift.

When I held my baby girl in my arms for first time, I really believed she had been born into a world of endless possibilities, where being a female would never hold her back.

But, already, there were hints that that promise had failed to turn into reality. With the benefit of hindsight, I now see that by the time I became a mother, there were already the first signs that the progress we had taken for granted was starting to go off the rails.

By the early 2000s, the fact that a woman could choose to wear anything she liked was becoming twisted into the idea that in order to appear truly confident it was best to wear virtually nothing at all. Women stripped thinking it made them powerful, only to find that, far from getting respect, their willingness to liberate themselves from their clothing was turned back against them in lads’ mags and music videos. Sex tapes which once ruined careers now created them, perpetuating the idea that sex was a quick way to buy legitimate celebrity and make money. Brazilian waxes to strip adult women as naked as little girls, and which also mimicked the hairlessness of females in porn, had started to be seen as ‘empowering’. Yet, as questionable as I personally felt these decisions were, at least these were adult women, making adult choices.

But when little girls started to get sucked in by this undercurrent, and began judging themselves by adults’ sexual standards fashioned by porn, a whole new set of previously unseen and extremely toxic effects started to emerge.

To be honest, before I wrote the first version of this book on the creeping effects of this culture on our daughters, Lily was seven and I was in shock. Like many parents, I initially believed that if I pressed enough towels to the door I could keep those toxic fumes of early sexualisation out of my home. But then one day Lily came back from primary school and told me some of her playmates had been calling each other fat in the playground and that, as a result, she and her friends had been swapping diet tips. Then a few weeks later Clio, then four, came home from a school dance club, singing that she had ‘gloss on my lips and a man on my hips’. It seemed her dance teacher had not thought to question if it was a good idea to devise a ‘bootylicious’ routine set to the Beyoncé song ‘Single Ladies’ for a group of nursery age children. It was then I knew I couldn’t stop the fumes, because they were already in the air my girls were breathing.

So I realised that if they were to stand a chance of growing up strong, I couldn’t hide them from these things. Instead, I’d have to raise them in such a way that they could manage and filter these messages themselves.

When I talked about how to do this in the last edition of this book, there were some voices asking what all the fuss was about. One sociologist on ‘Woman’s Hour’ demanded to know why I was denying my girls the right to their sexuality. In fact I was helping them push back against a culture which was defining their sexuality before they had a chance to define it for themselves.

‘Moral panic’ is a phrase I often hear wheeled out to silence concerns about how girls are affected by these messages. But is it really prudish or panicky to ask that our children enjoy uninterrupted childhoods where they are not beset by self-consciousness about how they look as soon as they are old enough to recognise themselves in the mirror?

Modern life – and the way we adults express ourselves in it – may be evolving at a breakneck speed, but our daughters still need to go through the same developmental milestones in the same order as they always have to become emotionally healthy adults. Just because a child has the opportunity to dress up like a grown-up on the outside, doesn’t mean she is ready to be treated the same way on the inside.

My girls, and yours, probably see more images of physical beauty in one month than we saw in our entire childhoods. They are growing up in a world where their worth is measured by how closely they match those ideals. No matter what’s going on in their brains, beauty has become an obligation. Yet even if they achieve those ideals, it’s never enough. Girls today are caught in a double bind. If they fail in this beauty contest they are made to feel like they don’t count. If they succeed, ‘pretty’ becomes all that they are.

As a parenting writer with a wide-ranging remit to investigate the ongoing effects of these developments on our children, I have been in a privileged position to see how the situation is evolving. From this vantage point, I have not only seen how sustained this assault is, I have also seen how fast-moving it has become. When I originally wrote on the subject, sexting was almost unheard of. Now the latest research says teens accept it as a way of life. Self-harm, scarcely known in schools a few years ago, has soared – there has been a 41 per cent increase in calls from children to their helpline about self-harm over the last year alone, according to Childline.

But self-harm has not just ripped through our classrooms in the form of cutting. Virus-like, the internet has enabled it to morph into the new phenomenon of cyber self-harm, where children post hurtful comments about themselves in order to attract strangers to troll them and help put their self-loathing into words. When I last assessed the situation, size eight was the Holy Grail of thinness. Now it’s size zero. ‘Thinspiration’ and thigh gaps have also become aspirational, making our girls believe they should disappear, quite literally, into thin air before they’ve even grown into their bodies in the first place.

Then of course there has been the evolution of pornography. Naturally, it’s porn’s job to be graphic. That’s the whole point. What was surprising a few years ago was how easily accessible it was to anyone, of any age, who could type the word ‘sex’ into Google. What’s surprising now is how much more violent and degrading porn is becoming in order to maintain the novelty factor.

The pace of these changes, powered by a constantly evolving internet, is so fast, we can’t simply firefight one crisis after another. Instead, as parents, we need to be a firm centre in the middle of this storm. That’s why this book takes a three-pronged approach.

So that we start off from the best possible position to protect our girls, the first section deals with how to organise our own attitudes and ideas, so that the conscious, and unconscious, messages we send to our girls are healthy, clear and consistent.

The second part looks at how, by building self-worth in our children, we can go some way towards inoculating them. If we can create a strong core of self-belief in our girls’ formative years, they will be better able to stand firm against the pressure to reduce them to nothing more than their physical beauty. By really opening up channels of communication in the tween years, we have a chance of staying closer to them when the going really gets tough. The good news is that the latest research shows the best defence against bad influences is you, the parent. One upside of the sexualised culture is that fewer topics are off limits when we talk to our children – and there really are age-appropriate ways to tackle every subject, from sexting to STDs.

The third section looks at the world through the eyes of our children. It looks at how they see it – and how we need to teach them to discover for themselves how to discern what’s good and bad. From sexting to self-harm, from phone addiction to friendship problems, this part will look at the most common challenges parents face when trying to keep their girls strong. It will help you comprehend those challenges so you are in the best position to understand them. Then it gives you the practical tools to help you and your daughter push back. It will offer dozens of achievable ways you can help to tone down, if not turn off, the effects of ‘raunch culture’.

For the sake of our girls, we can’t forget about the well-being of boys. They are their future friends, boyfriends and husbands, after all. Just because girls were the first in the firing line doesn’t mean that our sons aren’t suffering too. Boys are also pressured to behave in the macho ways they see displayed in pop, porn and video games. They are fast creeping up on girls in terms of how much they worry about their appearance. They are expressing their need to conform to stereotypes with ‘bigorexia’ – the need to bulk up to look buff. They are also often miserable because they are struggling to connect with girls the way they’d like to. In the same way that we are talking about femininity, boys also need a chance to talk about masculinity. Ultimately our goal should be for both sexes to have dignity during their childhoods.

But until that happens, we need to help our children become strong and insightful enough to wage that campaign. As a mother of girls, my focus in this book is on my daughters, but there are still plenty more books to be written by fathers of sons, to make boys just as self-aware.

None of this can happen overnight. The sooner we begin, the better. The tween years – the ages between seven and twelve – offer a critical window when parents can help girls develop an unassailable sense of self. It’s during this period that our power to positively influence our children is also at its peak – before the inevitable separation of adolescence means our daughters’ peers begin to drown us out. If we really work at staying connected to our girls in those years, we have a better chance of being able to guide them when life becomes more challenging.

Our society won’t stop sending these destructive messages. But by becoming aware, we can filter the air around our children so they can breathe deeply and grow stronger.

Don’t see helping girls reject these negative messages as one more job to add to your already packed to-do list. By becoming a conscious parent, by talking more and providing daily subtitles to help your child to understand life, you will communicate better and the conversations you have will be livelier and more invigorating. Your bond will be stronger. Your girl’s knowledge of herself will be deeper and her respect for you will be more profound.

The younger you start, the stronger the roots she will have to grow sturdy enough to resist the temptation to degrade or sacrifice any part of herself when the pressure piles on in her teenage years. But all is not lost if we miss that window. Just by becoming a more aware parent today, you can help make your daughter more media-aware and emotionally literate. In the two minutes you take to show her how a magazine photograph of an ultra-skinny perfect model has been airbrushed, you have taught her not to hold herself up to an image of perfection that doesn’t exist. By talking about and explaining what’s happening around her today, you can shelter her against the drip, drip, drip erosion of her self-worth. That’s why this book offers many suggestions for parents of girls of all ages. With the best will in the world, it would be impossible to put them all into practice. As you know your daughter best, you need to pick the most appropriate ones for you and your family.

Parts of this book will be upsetting. Facing up to what’s out there – and making our girls more resilient and robust – isn’t going to be easy. You may even have to come back to the sections meant for older girls if they are too much for now. As you read, you may also have to question if the creeping sexualisation of society has affected your values too. You may have to ask yourself if you have unknowingly added to the pressure by joining in the push to make our daughters the brightest and the best. But if all this helps your girl to be a little more true to herself – rather than feel she has to fit into today’s stifling stereotypes of ‘sexiness’, beauty and perfection – then you will have won back her freedom to live without these restraints and develop at her own pace.

If we don’t face up to it, the price is high. When girls wander through life thinking there is something wrong with them it makes them feel anxious, lost and powerless. Unsure of how to make themselves feel whole, too many try to fill this emptiness with fixes like diets, meaningless sex, self-harm, oblivion drinking and drugs. The problem is that because these influences are inundating them at such critical times in their lives, these wounds don’t always heal, and without being shown how to fill this void, they will carry these insecurities into their adult lives.

Public Health England says that one in ten children now has a mental health issue, and a third of teenagers feel ‘low, sad or down’ at least once a week. According to the All Party Parliamentary Group on Body Image: ‘One in four seven-year-old girls have tried to lose weight at least once.’ More than a quarter of children say they ‘often feel depressed’ – and the thing that makes girls most unhappy is how they look. It’s heartbreaking that as early as nine and ten, our daughters are already judging themselves as losers in the beauty contest of life.

One of the most insidious and least recognised effects is that our girls are also losing their voices. By the time they are ten, 13 per cent of girls aged ten to seventeen would avoid giving an opinion. The reason? They don’t want to draw attention to themselves because of the way they look.

As a mother of two girls myself, I wrote this book because I do not want my children, with all their accomplishments and wonders, to be judged solely on appearance – and to feel silenced when they want to talk back and defend themselves. I do not want them to be exposed at every turn to a hyper-sexualised culture where sex is only a commodity and women are rated mainly on how ‘hot’ they are, or most of their headspace gets used up trying to work out what’s wrong with them, when they are more than good enough as it is. My daughters don’t deserve to feel like this – and neither do yours.

PART ONE

Building a Strong Foundation

US AS PARENTS

Mum and dad, can I have a nose job please?’

It’s just after 10am in Harley Street, and the doors have opened at one of the capital’s larger plastic surgery clinics. At the reception, patients are being greeted by a rank of identikit receptionists in black suits and red lipstick, like the all-girl rock band in the ‘Addicted to Love’ video. Now dotted around the beige upholstery, the first intake of customers is busy leafing through a stack of celebrity magazines. My job this morning is to ask them why they are here. After all, the number of people undergoing plastic surgery in the UK is rising at the fastest rate in history. So why exactly has this need to look perfect become such an epidemic – and how, at a time of economic hardship and high unemployment, do people find the money?

Because my brief was just that, I had no other expectations. But as the waiting room began to fill, it was striking to see that so many of the women here were in their late teens or early twenties.

Flawlessly made up and doe-eyed, Amelie has the petite face and body of a young Audrey Hepburn – and the pert boobs, outlined in a skin-tight T-shirt, of a glamour model. In fact, she works as a cosmetics sales assistant in a nearby department store, and she is back for a post-operative review after getting her 32B boobs boosted two cup sizes ‘for confidence’.

The £4,500 cost of the operation is probably not far off a quarter of her yearly take-home salary. But, like so many of her generation who can’t afford to move out, Amelie lives at home – and anyway her mum and dad paid for the surgery.

‘I told them I wanted them done and they said: “OK, if that’s what you want.”’ she explains matter-of-factly, as if her parents were paying the down-payment on her first car. ‘They didn’t worry. They said: “If it makes you feel better about yourself, then that’s fine.”’

In the other corner of the room, I approach Elaine, 20. With her tongue stud and skinny jeans, Elaine looks like more like an off-duty member of a girl-band than the legal secretary she is. She recently had a nose job, once again paid for in part by a loan from the bank of mum and dad.

‘I know it’s going to sound really funny, but there was nothing wrong with my old nose,’ she insists. ‘It just looked a bit funny in pictures. My friend had it done when she was eighteen. Plus everyone’s doing it. Surgery is getting younger these days. Six of my friends have had boob jobs. One went up to a double F and she loves all the men paying her attention. As soon as you find out from your friends that it doesn’t hurt that much, there’s nothing to stop you. The moment I woke up from my nose job, I asked about a boob job. I am still thinking about it.’

Because it’s her first session, Courtney, eighteen, is being accompanied by her mother this morning. They have travelled from Kent to start a course of £1,200 laser treatments to get rid of Courtney’s stretch marks. Again, flawlessly made up to airbrush standards – and a size six in skinny jeans and a T-shirt which is cutaway to reveal her tiny waist – Courtney continually smoothes down her waterfall of glossy auburn hair.

As if she is about to being cured of a life-threatening disease, Courtney explains that she developed ‘terrible red lines’ across her stomach and thighs when she put on two stone after starting the contraceptive pill. Now, with just a few months to go before the start of a performing arts course, both mum and daughter are frantically trying to get rid of them for fear they should stand in the way of her career.

Once she’s gone in for her treatment, mum Justine confides why, as a responsible parent, she felt she had no choice but to do something. ‘It’s true the treatments are quite expensive. But what choice have you got when something like this is ruining your daughter’s life? It’s wrecked her social life. When her friends ring her and ask her to join them on sleepovers, she says no because she can’t bear anyone to see her in her underwear.’

‘I saw her sitting there with the tears streaming down her face. It was heartbreaking. She kept saying: “Why has this happened to me, Mum? How could this happen to me?”’

University student Louise is also here courtesy of her parents’ generosity, although with only the tiniest bump on her nose, it’s hard to foresee how her life will change post-rhinoplasty. But her elder sister had already been treated to surgery by their parents to tidy up some loose skin after losing weight, and, so that they were absolutely fair, her parents told Louise that she could think of something to have done too.

It was just a snapshot. But as I interviewed more girls during my research for this book, I found almost every young woman has a notional shopping list of some fault she feels has to get ‘fixed’. Indeed, a study by Girlguiding UK found that 12 per cent of 16- to 21-year-olds would consider cosmetic surgery. The result is that market researchers now consider young people the prime plastic surgery growth market. In recent years, Mintel has found that it’s the number of young people considering cosmetic surgery that has gone up most sharply. Almost six in ten 16- to 24-year-olds – young people in the prime of their looks and attractiveness – want surgery to improve or ‘correct’ their looks.

The only thing that stands in their way is money – but with parents increasingly willing to foot the bill, that’s becoming less of a barrier to ‘fixing’ what they believe is wrong with them.

Of course, it’s painful for any parent to witness the anxieties teenage girls go through about their looks. But what was sobering was the quality of the reasons these young women had for going under the knife. As I remembered, plastic surgery used to be undertaken to fix flaws that caused crippling insecurities and unhappiness. Yet the main explanations I heard that day were that their friends had had something done too, they wanted to look better in pictures – or just because they could.

Today, such treatments are seen as quick, easy and less invasive – with women feeling that if they are out there, it’s their obligation to use them to fit into today’s beauty standards. None of the women in the waiting room cited celebrity culture. But then it’s so pervasive and ingrained that most girls grow up never having known any other ideal but perfection. Most learned about makeovers from TV shows at their mothers’ knees.

But far from trying to talk their girls out of it, or attempting to put these concerns into perspective, what surprised me was how many parents were prepared to foot the bill. Whatever objections they raised in private or in the run-up to the operations – which I was not privy to – they still handed over their credit cards.

Like mentors on The X Factor, in the final analysis they went along with the belief that cosmetic enhancement – and a perfect cookie-cutter appearance – is what a modern girl needs to get on in life.

For even younger girls, the trend is echoed in the rise in the child beauty industry. Ten years ago, there were virtually no mini beauty contests in Britain. While the French Government has now moved to outlaw them, there are now more than 30 in the UK, thanks, in part, to the instant fame bestowed by reality television programmes like Toddlers and Tiaras.

More than 12,000 girls are entered into the Miss Teen Queen UK pageant every year alone. Yet none of this would be happening without the parenting drive and cash to make it happen. As Cheryl, a mother I interviewed after she proudly paid for not one, but two of her daughters to have boob jobs the moment they turned eighteen, told me: ‘To me, [the operations] are the best things the girls have ever done.’

Rather than question the culture that made her girls sob into their pillows every night because they saw themselves as ‘flat-chested’, Cheryl, 49, insisted: ‘I think it shows I’m a better parent. After they had the op, it was like watching two flowers unfurl.’

Far from curing this restlessness about their appearance, it seems that fixing one perceived flaw just leads girls to worry about another. Before the wedding of Cheryl’s older daughter a few years later, perhaps it should not have been a surprise to hear that the bride-to-be prepared for her big day by getting her lips plumped and her Botox done, despite being barely in her twenties.

It would be unfair to single out any one mother too much. Despite how some of our values are affecting our daughters, we parents are responding to the influences around us. Most mothers genuinely believe they are doing their best to help their girls get on in life.

This attitude that girls need constant improvement is even catching on in primary schools, the one bastion where we might hope learning is prioritised over looks. Yet over the last five years, prom nights have become de rigueur for children as young as seven, and proud mums and dads don’t hesitate to fork out small fortunes on make-up artists, Barbie-doll dresses and limos. Indeed, when I wrote my last book on girls, most weeks there were stories in the papers of mums putting put six-year-old children on strict calorie-controlled diets, bleaching their teeth and signing them up for pole-dancing lessons, lest they lose out in life.

The stories which hit the headlines were, of course, extreme examples that few parents reading this would identify with. Yet, though the manner and style of presentation might vary, this is a tendency filtering through all sections of society. They may be less newsworthy, but I’ve known mothers at the nation’s most exclusive schools who talk proudly about how they paid to have their thirteen-year-old daughter’s teeth veneered to give them a ‘Hollywood smile’, or how they took them to a top salon to get £250 highlights because their daughter’s ‘mousy’ brown locks ‘didn’t make them stand out’.

But just as I had to look deeper at my own values, and examine whether my best intentioned references to ‘healthy foods’ and my regular gym sessions had made my daughter Lily start to believe that it’s part of a female’s job description to fret about her body, it helps to go back to the source.

Take yourself back to the moment you knew you were having a baby girl. Was your first thought to imagine how pretty she was going to be, or the lovely dresses you were going to put her in? If you’re also the parent of a boy, ask yourself if you felt something similar when you learned you were having a son. Would it be fair to say that his outfits and how handsome he might be were lower on your list of initial concerns? It’s a tough thing to admit, but if we are going to fight against our girls being judged on how they look, we have to start by examining our own expectations – and how they have been shaped in us over the last twenty or 30 years. After all, if we were born during or after the sixties, we were the first generation to grow up in a world dominated by television. As TV became our main national pastime, as children we quickly picked up that, for a woman, being thin and beautiful equals being sexy and successful.

In our lifetimes, we saw the explosion of reality stars, WAGs and manufactured girl bands who have sent the lesson that you can be rich and famous without talent. Pretty and pushy is all you need. The fact is that as mothers we have been under siege too. We have also been affected by the media messages which tell us that we can never be beautiful or thin enough. As these celebrities have racked up continuous attention and impressive wealth – and reality TV has made this feel within the grasp of everybody – have we not also signed up to the idea that females needs to look a certain way to get on in life?

Even as grown women, we may never have known the peace of feeling good about our bodies. As I write, a record-breaking two out of three women have tried to lose weight in the past year – up from 63 per cent the previous year to an all-time high of 65 per cent, according to Mintel. Without realising it, have we also come to covet a celebrity lifestyle and appearance for our own children and equate beauty and thinness with power?

Of course, through the ages, parents have always prized their daughters’ attractiveness. Because the faces of our children – their smooth skin, shiny hair, large eyes and soft features – are the prototype for adult perfection, little girls are, by their very nature, beautiful. This is such a difficult area for parents, because we are damned if we do address appearance with our girls, and damned if we don’t. We can’t pretend that looks don’t matter one bit. The acute sensitivity of girls on this topic is such that those with parents who never mention it assume it’s because they are ugly. So simply not attaching any importance to appearance whatsoever is not the answer.

However, it’s how much importance we attach to looks in a society already obsessed by looks – where everyone is measured on a sliding scale of perfection – that is now key. So while we should feel free to acknowledge beauty, we have to be even more careful that we try not to fall in with the trend of making it the most important quality about our girls. We need to make it clear that their beauty is a small part of what they are – not who they are.

Starting early in their lives, it’s vital to prize other values – like kindness, honesty, generosity, self-awareness and self-acceptance – that often get drowned out in a culture of superficiality. Rather than encourage the draw towards celebrity and consumerism, we need to try to divert them away from the identikit ideal of feminine attractiveness – perma-tanned skin, hair that will only pass muster if it’s glossy enough for a shampoo ad and a lithe, fat-free body – towards qualities which are not visible. If, as their most important role models, we endorse society’s message that looks are the most important thing about them, we don’t equip our children for success. We set them up for a lifetime of disappointment.

Why parents feel powerless

Being a parent of girls is a tough job. But it’s even tougher for the families of today who are trying to screen out so many more negative influences on their daughters’ healthy development. Compare, for a moment, the influences on your own childhood, with those on your daughter’s.

Probably, during your childhood, if you watched TV alone, it was mainly in the prescribed after-school period, or on Saturday morning when there were shows created for kids your age. Certainly when I was growing up in the Seventies, there was just one TV, and the whole family would gather round to watch variety programmes designed for everyone, like This is Your Life or The Morecambe and Wise Show. True, there was sexism, much of it a spill-over from the Carry On humour of the Sixties. Sometimes, the TV showed women as passive sex objects, like in Miss World. But still, the only place you could be guaranteed to see a topless woman was not on TV, but on page three of the Sun.

Though it may have been implied, there wasn’t nearly as much sex in our media – and certainly nothing of the intensity we have now. Anything much stronger than a kiss or a mild swear word was unheard of before the 9pm watershed, which was rigorously policed. Compared with children growing up today, our childhoods were androgynous.

Because it’s all happened relatively quickly, it’s hard for us as parents to take on what our daughters’ childhoods are really like, and how the world looks from their point of view. With sexuality and body image now so deeply woven into music, advertising, TV, magazines, fashion and the internet they face, it’s understandable that many parents already feel defeated. They feel society has moved on and that it’s a fact of life they have to live with.

When I first wrote about this three years ago, the families I spoke to handled creeping sexualisation in a variety of ways. Generally, they sat on a sliding scale between prohibitive – believing they could screen it all out – and permissive – thinking they had no choice but to go along with it. In the period since then, I have noticed that we are not as shocked anymore. That, worryingly, we have come to accept aspects of sexualisation, like girls of eight looking and acting like teens, without question. It is on the way to becoming normal. So, before we start looking at where we need to go from here, it may be worthwhile to look at where we, as parents, are starting from. While the range of viewpoints that follow may not be a definitive list, look through to see if any of these preconceptions match your own:

‘There’s nothing we can do – so why try?’

Among the many parents I interviewed for this book, there was a real sense of fear and powerlessness. Many had taken the route of weary surrender. ‘There’s nothing we can do’ was a common refrain. Indeed some have already given up or accepted growing up sooner as the status quo.

Mothers and fathers told me they didn’t know where to start because the internet and the media felt too vast and out of control. Everything was moving too fast. These are parents who feel drowned out as advertisers, retailers, programmers, video makers and negative peer pressure ride roughshod over their influence.

According to a survey of 1,000 parents of children aged under eighteen, one in five parents feel they have little or no control over what their children see on the web anymore, and a quarter feel they have lost control over what their children do on social networking sites.

The parents in this category often start off being restrictive but lose hope when they start to believe they are fighting a battle on too many fronts. Indeed a report by the British Board of Film Classification found that, by the time their children were fifteen, most parents believed it was ‘game over’ and that kids were so tech-savvy they could no longer control their child’s viewing in any way.

But it’s far too soon – and far too dangerous – to fall into a state of paralysis. While it’s true that we can’t shield our children, we can inoculate them from the effects by decoding – in an age appropriate way – what is happening all around them. By helping girls to question the pressures placed on them, we really can help them work out for themselves what is good and bad for them. Furthermore, far from being impotent, parent power is still a force to be reckoned with. While responsible corporations do like profits, they also hate bad publicity. Deep down, I still believe society knows it has a responsibility to collectively look after our children. So we need to ask why the vast social networks, making billions in advertising, don’t have the moderators to monitor or act on the cyberbullying, trolling or images of violence and cruelty that run riot on their sites.

It took just one mother of two, Nikola Evans, to get Asda to apologise for and withdraw a display of padded bras for girls as young as nine from an aisle at their Sheffield store. Following a national outcry from parents and campaigners, Primark removed padded bras for seven year olds from its shelves, while Tesco also stopped selling ‘toy’ pole-dancing kits.

Advertising, TV and other forms of media also have complaints bodies – but they are, all too often, woefully underused. Remember, all it usually takes is a single complaint to launch an investigation and move society an inch closer to being more conscious and accountable for the welfare of our girls.

‘If I just say no, it won’t happen to my child.’

Early in our daughters’ childhoods, when they are still babies and toddlers, it’s reassuring to tell ourselves that if we don’t buy them Bratz dolls, park them in front of the internet or computer games for hours or dress them in T-shirts with slogans like ‘So many boys, so little time’, we can protect them from negative messages that damage their well-being. But these influences are not a tap you switch off. They are in the air they breathe, and as your child gets older, peer pressure will play an increasingly large part in the decisions your daughter makes.

If we simply try to prevent our girls from ever seeing or hearing negative messages, they will never get the chance to work out for themselves how either to spot – or to cope with – the dangers. We also risk them becoming so intrigued by the forbidden that, once they are out of our control, they become eager to try everything we’ve tried to keep them away from. Most of all what children need is to learn to judge for themselves.

Ultimately, it’s more realistic to equip your child and warn her what’s coming. Explain where the pressures come from and the commercial realities behind them. Explain that marketers target young girls because they are the most naïve consumers, and that the ads only work by playing on girls’ insecurities and desire to fit in. Make it an ongoing conversation, and help her to see the bigger picture. By decoding what is going on around her as she experiences it, you will help her reject these messages.

‘I don’t want to tell her anything because it will take away her innocence.’

Many parents also feel understandably confused and panicky about how much information to give to prepare their children. They feel afraid of robbing their daughters of their innocence by telling them of the pressures they might come under.

As parents, so many of us find it painful to acknowledge when our girls are ready to start learning more about sex. I spoke to many mums who couldn’t bear the thought of sex education classes, even in Year Six, because they believed there was no need. But the risk is that if we don’t tell children about sex, then the internet will get in there first – and sooner than we think. If our girls do end up learning about sex – as so many do – by stumbling across pornography before they’ve even had their first kiss, this is going to be as far away from the healthy messages you want to give them as possible.

Talking to your children about sex won’t encourage them to go and do it. Quite the opposite. More than 250 studies have found that the best way to protect girls against early sexual behaviour is for them to be responsibly informed about sex in the first place.

Frightening though this may feel, there really are always warm, non-scary, age-appropriate ways to talk about everything. But don’t keep steeling yourself to launch into the big ‘birds and the bees’ chat that never quite happens. Make it an ongoing dialogue with your daughter, and add more detail as and when she needs it. Let her know that sex should have context and meaning. As parents, we need to accept that it’s a conversation that may feel strange to start off with. But it’s better to accept what’s happening, because it will happen whether we want it to or not. Once you get going, you may even warm to the subject – although don’t tell her more than she needs, you will end up confusing her. In the final event, you won’t be with your daughter when she makes her sexual choices – but if you’ve talked her through them, she’s likely to choose the safer, more meaningful options.

‘My daughter’s a good girl. She’s not interested.’

This was a common refrain. In fact, very few parents I spoke to – even those with older girls – were aware of their children seeing sexual content like pornography as anything other than a one-off or completely by accident. The fact that girls are excellent secret keepers helps parents live in this bubble.

Among the many studies to paint a rather different picture is a report by LSE which found that while 57 per cent of children between the ages of nine and nineteen have seen porn, only 16 per cent of their parents knew. When it comes to knowing whether or not their daughters are having sex, parents are also wide of the mark. Studies have found that in 50 per cent of cases, mums and dads who believed their children were virgins were wrong.

So be realistic. Difficult though it can be to face up to, you’ll be in a stronger position if you accept your children as sexual beings, than if you avoid the uncomfortable truth that they are.

‘Everyone else’s kids are doing it – so I can’t stop mine.’

Many parents feel that however much they protect their girls, they will just hear it all from their peers at school anyway, so what’s the point? Others say they don’t speak up because other parents aren’t saying much either, so that probably means it’s OK.

Underlying this is also the worry that they won’t look ‘cool’ if they are the only ones who don’t let their daughters sign up to social networks or see films that are rated for an older audience.

But just as you would hope your child would stand up to peer group pressure, it’s important you do the same. Make your own decisions. It takes a strong parent to say no when most of the others are saying yes. I know of one mother who vetoed a plan by a group of other mothers to have a ‘makeover tent’ at their primary school fête. She says they now ignore her, but she’s impervious because she truly believes she did the right thing for her nine-year-old daughter.

When it comes to going against other parents, what’s more important? The fact that, at worst, you might be viewed as the killjoy at the school gates, or protecting your child and possibly helping other parents be more conscious about the messages they are sending out?