22,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Serie: Ceramics

- Sprache: Englisch

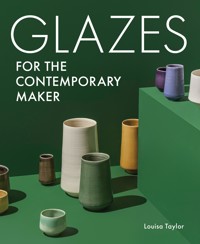

Quite simply, everything you need to know about glazes. Glazes for the Contemporary Maker is an essential guide for all ceramic artists and potters looking to expand their knowledge and gain confidence in this dynamic area of ceramics practice. The book provides a holistic approach and serves as an introduction to glaze chemistry, materials knowledge and methods of application via detailed step-by-step guidance and informative text. Packed with over 200 illustrated glaze recipes, it is an indispensable reference, which covers everything from shiny, opaque, matt, crystalline to special effect glazes that span across the temperature ranges. Supported by impressive examples of work by leading practitioners, this book provides inspiration and a source of practical tips and advice, allowing you to learn and initiate your own creative path through this exciting subject.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 253

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Albert Montserrat, Frog #1 White and Black Vessel (2021), Height: 19.5cm. Thrown porcelain vessel, finished with a combination of glazes and fired to 1300°C (2372°F/cone 10).

CONTENTS

Introduction

Chapter 1: Establishing your Glaze Practice

Chapter 2: Glaze Materials

Chapter 3: Preparing and Applying Glaze – Methods and Techniques

Chapter 4: Firing

Chapter 5: Glaze Testing

Chapter 6: Glaze Experimentation and Decorative Techniques

Chapter 7: Common Glaze Faults and Remedies

Chapter 8: Glaze Recipes

Glossary

Appendix 1: Orton cone reference chart

Appendix 2: UK-US material equivalents

Suppliers

Contributors

Bibliography

References

Index

INTRODUCTION

Glaze is an integral part of the ceramic process and offers great potential for intrigue and discovery. Through the alchemy of materials and application of heat, it is possible to orchestrate unique outcomes that act as a visceral record of the process and represent the artistic pursuit of the individual. The thrill of opening the kiln and being rewarded with a piece that exceeds expectations is very addictive and can be the driving force behind establishing a successful creative identity.

Anna Silverton. Group of porcelain vases in yellow and grey soft matt dolomite glazes (2021). H: 55cm. Finely wheel-thrown porcelain, fired to 1280°C (2336°F/cone 9).

On the flip side, there is a perception that glaze is a very technical or overly complex subject, and this can deter many from exploring it in greater depth. This assumption is not surprising considering the high-risk factor and failure rate that is often associated with this area of ceramic practice. Understandably, if a great deal of time and effort has been invested in the production of a piece, one is more likely to be risk averse when it comes to deciding on the glaze choice or its application. Here, the focus of this book is to help demystify the many different aspects of glaze practice and clearly explain the principles of glazing, the materials used and methods of application via detailed step-by-step guidance and informative text – drawing on my own experience of over twenty years as a ceramics practitioner. The aim is for you to feel sufficiently confident and assured to instigate your own glaze journey.

One of the biggest misconceptions about glaze is that you need to have a scientific mind to be successful, but in fact just a general interest in glaze is a great place to start. The whole process is very visual and soon you will find yourself wondering why certain results happen or how to control your glazes and develop them into something distinctively unique to you. As you gain understanding of specific glaze terminology and secure basic chemistry knowledge, this will stand you in good stead to progress to the next level of proficiency.

Throughout this book, the content is intended to be accessible, informative and to prompt intrigue. The principle here is to first instil a foundation and grounding within the subject that will elevate your knowledge to carry forwards and continue to build on. There are many different approaches you can take but key attributes to be successful at glazing would be to just have an enquiring mind – don’t be satisfied with your first results; continue to experiment, take risks and be inquisitive about the process. Try not to be deterred by what you don’t know – one of the great joys of glaze is that so much can be learned by simply having a go and establishing deep understanding and knowledge as you progress with experience. The aim of this book is to ignite a passion for glaze and be a go-to guide that will support you through your learning and ultimately, enable you to determine your own creative pathway through this dynamic field.

Louisa Taylor, Ven set of nesting bowls, H:15cm. Thrown and altered porcelain, fired to 1280°C (2336°F/cone 9). The glaze palette for this piece was inspired by museum collections of eighteenth-century porcelain wares.

Chapter 1

ESTABLISHING YOUR GLAZE PRACTICE

If you are coming to glaze as a complete novice at the very beginning of your glaze journey, or as an experienced practitioner keen to build confidence and new skills, you might be feeling a little apprehensive or even intimidated about what it entails. However, by adopting a pragmatic approach – as well as an inquisitive mindset – you will soon be able to unleash a flair for glazing and strong command of your own methods. Be sure to shake off any beliefs that glazing lets you down; much like other aspects of ceramic practice such as learning to throw a pot on the pottery wheel or constructing a hand-built form, the more time you invest in honing your techniques, the more likely it is that you will achieve successful outcomes. The aim of this chapter is to introduce to you the fundamental elements of what constitutes a glaze and how to develop and define your practice going forward.

Tessa Eastman, The Kiss (2021). H: 42cm. Glazed ceramic. Tessa Eastman’s lively sculptures are complemented by the application of highly tactile crater glazes and vivid use of colour.

ORIGINS OF GLAZE – A BRIEF HISTORY

Many glazes we use today have been developed over the course of time by civilizations dating back thousands of years. The earliest known use of glaze originated from Ancient Egypt (or Mesopotamia) around 4000 BCE in the form of Egyptian paste, or Faience. Sourced from natron, a naturally occurring rock consisting of soluble alkaline salts, the mixture was combined with copper-bearing minerals, formed into a paste and dried. The salts migrated to the surface, forming a crust. When fired, the paste melted into beads of opulent turquoise-blue glaze and was commonly used for decorative artefacts and jewellery (a recipe for Egyptian paste is included in Chapter 8). This technique later evolved into the practice of applying glaze materials to the surface of wares to create a fused layer of glass, although it was not uncommon for the glaze to flake off the ware after firing or craze badly.

The discovery of lead as a glaze material was an important advance and is believed to have originated in ancient Syria or Babylonia. Here, the practice involved dusting the wares with a fine, powdery coating of the lead ore, galena, which was then subsequently melted at low temperatures. Lead glazes were considered more durable and offered a superior quality to earlier alkaline predecessors. Various oxides such as copper, iron, manganese and cobalt were added to produce colourful glazes. This knowledge spread to China, with some of the earliest examples of lead-based glazes dating to 500 BCE, then reached the Middle East and Europe. Early English, lead-glazed slip-decorated pottery made in Staffordshire offers some particularly fine examples. There was no awareness of the dangers of lead poisoning until the nineteenth century.

In China, the development of the down-draft chamber kiln is said to have initiated the progression of high-temperature firings of above 1200°C/2192°F. The kilns were fuelled by wood and the potters observed how the fly ash that was blown around the kiln chamber during the firing settled on the wares and formed a glassy coating on the surface. The Chinese potters of the Han dynasty (206 BCE to 220 CE) are largely credited with the development of felspathic glazes and for improving kiln efficiency and design. Beautiful celadons and iron-rich tenmoku from the Song dynasty (960–1270 CE) are considered to be some of the finest examples of pottery in the world.

The medieval Islamic potters of the Middle East imitated the elusive qualities of Chinese porcelains by coating bisque-fired pottery with tin glaze and applying intricate decoration using copper, cobalt, iron and manganese oxides. These techniques filtered through to Spain after the Moors invaded in around 711 CE, and by the late medieval–early Renaissance period it became known as Maiolica ware (later, Majolica – from the nineteenth century onwards) named after the ports of Malaga in Spain and the Spanish island of Majorca (Mallorca). This highly decorative style of tin-glaze earthenware migrated across Europe where it was known as Faience in Italy (also Italian Maiolica), and Delftware in the Netherlands and British Isles.

During the fifteenth century, salt-glazed pottery was developed in Rhineland, Germany and this became an industrious glazing method that spread across Europe, becoming a common practice in the UK. Silica-rich slips and oxides were applied to the raw clay wares prior to firing. As the kiln reached high temperatures, salt was thrown into the chamber, where it vapourized and reacted with the silica present in the clay body and slips – forming a layer of glaze in the process. This action was repeated over the duration of the firing until a sufficient coating of glaze was achieved. Salt-glaze pottery has a distinctive orange-peel texture and colours range from tan-orange, greys and cobalt blues.

Throughout history, it is remarkable to consider that some of the most beautiful glazes in the world that we know and use in modern ceramic practice were achieved largely by trial and error, without any of the scientific understanding and knowledge of chemistry we have today. Much of this knowledge can be accredited to the German chemist Hermann Seger (1839–1894), who during the nineteenth century worked in industrial ceramic production and developed the Seger system of analysis – or unity molecular formula (UMF) as we call it today, to understand and group ceramic materials based on their molecular composition. This is discussed in more depth in Chapter 2, but it is a useful starting point to introduce the key components of a glaze as we proceed through the text.

WHAT IS A GLAZE?

A glaze can be defined as a layer of glass fused to a ceramic surface. It is typically applied as a liquid to bisque-fired ceramic and is quickly absorbed, leaving behind a coating of dry powder on the surface. It is then melted onto the body at a high temperature in a kiln. Glaze is not the only conclusion to a ceramic surface, but it is fundamental for wares intended for use. A glaze layer provides an impervious seal to render the ware hygienic and fit for purpose, to aid cleaning and offer stain resistance. This is particularly important for earthenware/low-temperature pottery which remains porous after firing. Glaze can help strengthen the ware, offering more resilience to the knocks of everyday use. Another application of glaze is for decorative and aesthetic purposes, to bring artistic expression through the surface, uniting it with the form. Glazes can offer a broad range of appealing surface finishes from high gloss, translucent, dry matt, opaque, to highly tactile volcanic and oozy qualities. It can also be used to mask an undesirable fired colour of clay body with a more attractive colour, as well as enhancing carved texture or under-glaze decoration.

Glazes can be categorized into the following temperature groups (discussed in Chapter 4). A suitable glaze will have good maturation between clay body and glaze:

A selection of glaze tiles from the earthenware temperature range, illustrating the broad scope of colours and variety that can be achieved.

UNDERSTANDING GLAZE

Most glazes comprise ceramic materials, called oxides, which derive from minerals and rocks and are combined together in variable amounts to promote specific attributes, such as high gloss or mattness. The basis of a standard glaze consists of three principal components – glass formers (silica), fluxes and alumina (stabilizers).

Silica (silicon dioxide SiO2) is the principal glass-forming ingredient in all ceramic glazes. It is found in abundance on the earth’s crust, with the minerals flint and quartz being the most common source for glazes. Silica is considered refractory – by this, we mean it has a very high melting point of 1710°C (3110°F). This temperature would be incredibly difficult to reach in a kiln and too high for most clay bodies, which would melt. Therefore, fluxes have to be added in order to lower the melting point of the silica to a more attainable temperature, and one that is suited to the clay body and intended glaze. When two or more ingredients are mixed in certain proportions to allow the lowest possible melting temperature, this is called a eutectic.

Fluxes are primarily a group of oxides including sodium, potassium, lithium, calcium, magnesium, strontium, barium, zinc, lead and boron (boron being the exception whereby it is both a glass former and flux), which help control the melting temperature point of silica. During the firing, the flux operates by surrounding the particles of silica, breaking down the silica chains or the bonds between the silica molecules, causing the glaze to melt.

It is common practice for more than one flux to be used in a glaze recipe, and this function can be described as the primary and secondary flux. The main role of the primary flux is to lower the melting point of the silica, but a combination of fluxes can also promote useful attributes in the glaze including strength and durability. The secondary flux can improve the melt and give chemical stability, as well as desirable characteristics to the glaze such as enhanced colour tone, craze resistance, crystal growth, high gloss or matt surfaces. Examples of primary fluxes include sodium, potassium and lithium for high-temperature glazes, and lead and boron for low-temperature/earthenware glazes. Common secondary fluxes include calcium, magnesium, strontium, barium and zinc oxides.

The combination of silica and flux alone is enough to produce a glaze, but the result would be very runny and difficult to contain on the ware. Therefore, alumina (Al2O3), consisting of clay-type material is the third element in a glaze. The purpose of alumina is to bring stability and viscosity to the glaze and aid adhesion to the ware. Increasing the amount of alumina in a recipe can have the effect of making the glaze matt, resulting in dry or satin matt finishes depending on the quantity added. Sources of alumina include china clay, red clay powder, ball clay and feldspars (which contain alumina naturally).

Each material within a glaze has a role to play, providing either the glass former (silica), flux or alumina component. However, some materials, such as the feldspar group, for example potash, soda, nepheline syenite, by nature can encompass all three components and have the potential to make a glaze in themselves, although a very unrefined one. Another important consideration is that the behaviour of the glaze materials is largely determined by their chemistry – the glass formers (silica) are acidic, fluxes are primarily alkaline and alumina is generally amphoteric (neutral).

To help understand the role of the silica, flux and alumina, a simple experiment to try is to take a typical glaze recipe, such as the one below, and play around with adjusting the ingredient amounts to see how this impacts the final outcome, from shiny to matt results. Here the percentages of the primary flux (Cornish stone) and alumina (china clay) were increased and decreased whilst the other ingredients remained the same.

The test tiles were made from stoneware clay and fired to 1280°C (2336°F/cone 9) in an electric kiln (oxidized).

Shiny: The large quantity of flux in this recipe has produced a smooth, shiny glaze.

Satin: By reducing the flux and increasing the alumina quality, this has produced a semi-matt surface.

Dry matt: The high alumina and low flux quantity in this glaze has resulted in a very dry, refractory surface.

Colour

Most glazes when fired without any colouring additions are somewhere between transparent to white, depending on the component ingredients and quantity parts. Colours in glazes are achieved by two sources (the specifics of each material will be discussed in more depth in Chapter 2). These include oxides of metal, for example copper, cobalt, manganese, iron, chrome, nickel; and glaze stains – colouring pigments that are commercially prepared by the ceramics industry. When considering your glaze aesthetic, the choice of colouring agent will play a significant role in the outcome of the work. Oxides offer a wonderful array of tonality and depth. Glaze stains enable the user to create consistent, bright colours such as reds, yellows and pinks that would be difficult to achieve with oxides.

Tanya Gomez, Undulated – Group of Three (2022). H: 33cm (tallest). Thrown and glazed porcelain. The midnight blue piece was fired in oxidization and the two remaining pieces were fired in reduction to 1280°C (2336°F/cone 9). Here the bold use of colour accentuates the softness of the thrown forms and undulating rims.

Opacity

A glaze can be made opaque (not see-through) by the addition of a specific group of minerals called opacifiers which enable the glaze to obscure the colour of the clay body underneath. They work by resisting full integration into the molten glaze and remain as finely dispersed particles in the glaze. Opacity can also be caused by the presence of very tiny bubbles, or crystals in the glaze, which refract the light and induce a cloudy or milky appearance. Oxides and glaze stains can be added to the glaze for colour. Opaque glazes are a good base for making pastel shades or used as a base colour for applying decoration.

Examples include:

Tin oxide – bright white, used for Maiolica glazes

Zirconium silicate – white

Titanium dioxide – creamy white and mattness

Agalis Manessi, Mrs Nobuko with Fur Collar (2019). Dia: 20cm. Hand-built terracotta. Maiolica (tin-glaze), hand painted with oxides and stains, mixed with glaze, on the raw unfired glaze.

Texture

Glazes can appear matt if they are underfired or applied too thinly and there is insufficient glass former and flux to create the melt. An over-saturation of colouring oxides can also have the same effect. A true matt glaze will typically have a micro-crystalline structure whereby it is made up of tiny, microscopic crystals that scatter the light. Ceramics materials that contain magnesium, such as magnesium carbonate, dolomite and talc will produce satin-matt glazes, and are improved further with slow cooling. Higher proportions of calcium, such as whiting, wollastonite, dolomite (which contains both magnesium and calcium), and alumina – china clay, feldspars, will also produce matt glazes by increasing the melting point of the glaze.

Matt glazes are rarely transparent because the components that make the glaze matt also make it opaque. A way around this is to glaze a piece in a shiny transparent glaze and use a sandblaster or sanding tool to abrade the surface to take away the shine. Colourful matt glazes that contain calcium and magnesium can appear muted, in comparison to barium carbonate which is used to promote colour response such as bright turquoise blue (in combination with copper), as well as a broad range of smooth matt glazes. However, barium is toxic and should be avoided for functional wares. Strontium carbonate is deemed a safer alternative, but the compromise is that the colours are not as bright (seeChapter 2 for more specific information).

Louisa Taylor, Lemon Decanter Set and Beakers (2016). H: 22cm. Porcelain, thrown. Matt glaze coloured with yellow stain is contrasted by the shiny glaze on the neck of the decanter.

GLAZE PROPERTIES

Glazes are often named after the fluxing ingredient, or material which gives the glaze its characteristic trait, such as dolomite glaze – smooth, satin matt, barium glaze – textured, mottled matt or tin glaze – bright white glaze. However, there are a number of common terms used in practice to define specific properties of a glaze, which you will also see used in Chapter 8 to describe each glaze.

These include:

Transparent – a clear, see-through glaze

Shiny – high gloss, reflective glaze

Opaque – obscures the clay body underneath

Satin/eggshell – silky to touch

Semi matt – somewhere between a shiny and matt glaze

Matt – smooth, almost dry glaze

Dry-matt – very dry and rough to the touch

Crystalline – fine network of needle-like spurs within the glaze

Oil spot – mottled texture

Special effect, for example volcanic, crawl, flaky – unique surface qualities

Ceramic glazes offer a dynamic interplay between light and surface quality, and this can be exploited to great effect. For example, a shiny glaze has a brightness which is very appealing, whereas a matt glaze will rebound shadows and imbue a softness that invites interaction. The choice of a shiny, matt, satin, dry glaze surface, or even how we apply glazes can influence the way we interpret a form. This opens up much potential for exploration to experiment with texture and decoration. Here you see four identical cylinder forms, made from porcelain and fired to 1280°C/2336°F/cone 9 in an electric kiln (oxidized). Each cylinder has been applied with a different type of glaze and demonstrates the practical applications and unique benefits the glaze offers:

Matt Horne, Metallic Red and Blue Bottle Form (2022). H: 15cm. Porcelain, thrown. Crystalline glaze and post-fired reduced to produce striking pink-coloured crystals with turquoise halo.

Transparent shiny glaze: high shine, glossy glazes are very practical and durable, especially for items intended for utilitarian/functional use. Transparent shiny glazes applied over any underglaze or slip decoration will enrich the colours.

Matt glaze: Smooth, satin-like surface. Less suitable for functional wares as susceptible to scratching, but can be applied to the outside of wares, as well as for sculptural and decorative use.

Colour glaze: Colour glazes can enhance a form by highlighting texture, or be a feature in their own right.

Decorative: Here, glazes have been stamped with oxides to create a lively and playful surface.

SOURCES OF GLAZE

Glazes can be made by following a recipe and weighing out component ingredients to which water is added (seeChapter 5), or alternatively bought as commercially prepared ready-made glazes, all of which can be purchased from a pottery supplier – a directory is included in the Resource section. It is also possible to make glazes from locally sourced materials such as wood ash, chalk and quartz. The main focus of this book is to equip you with the skills and knowledge to confidently prepare your own glazes. However, it is important to acknowledge the role of ready-made glazes and the advantages and disadvantages of both approaches are outlined below:

Ready-made

If you enjoy ceramics as a hobby or have ever attended a pottery class, you may already be familiar with the use of commercially prepared glazes to decorate your pieces. The benefits of using a ready-made – and the reason they are so popular – is because they are so easy to use, the results are generally reliable and the range of colours, finishes and effects available to buy is vast. It is not uncommon for professional potters and artists to use a combination of their own glazes as well as ready-made glazes for specific tasks. Ready-made glazes are supplied either as dry powder to which you add water, or as prepared tubs of ‘brush on’ glaze. A drawback of ready-made glazes is the much higher cost of the product compared to making your own glazes. Ready-made glazes are specifically formulated by the ceramics industry, which ensures consistency but can make it difficult to then adjust and alter the recipe. However, on the flip side one could argue that storing large quantities of raw glaze materials takes up a lot of studio space, as well as accounting for the time and effort to weigh out and prepare a glaze. Ultimately, this really comes down to personal choice and preference. An option could be to buy a powdered glaze such as a transparent glaze or smooth matt and adapt it yourself by adding quantities of stain or oxide to generate a spectrum of colours.

Brush-on glazes are as the name suggests – glazes that are commercially prepared and ready to use straight from the tub. They are formulated to be very easy to use and are blended with an organic additive, such as CMC gum (carboxymethyl cellulose), which helps carry the glaze material, giving a smooth coverage that burns away in the firing. A brush-on glaze is applied in two to three layers for best results which can be more time-consuming in comparison to dipping a pot; it is also more expensive in terms of coverage. It is important to make sure the glaze container is sealed after use because brush-on glazes are prone to evaporating and can be very difficult to reconstitute if they dry out. One of the great benefits of a brush-on glaze is that it can provide a useful point to apply a specific colour or effect that might be too difficult to achieve by conventional means. For example, you could add dabs of ready-made glaze such as a bright red for a punch of strong colour, or use a special effect glaze to bring a distinctive surface quality to the work. Like any aspect of glaze practice, there is much experimentation to be had, so don’t be deterred from using it as part of your practice just because you didn’t make it yourself.

Make your own

When you are new to ceramics, the prospect of making your own glazes and getting to grips with the chemistry can feel very daunting, but you should think of it as the next step in your progression as a maker and an opportunity to inject your own creativity and imagination into a glaze aesthetic. Of course, you might have some mishaps along the way – that is all part of the learning process, but the benefit of developing your own glazes is the integrity and distinct connection to the maker they hold.

One of the main reasons for making your own glaze is the cost implications, particularly for scenarios such as batch production or glazes needed for high-volume use. By buying larger amounts of raw materials, you will be able to make much bigger batches of glaze which will last longer and save money in the long run. Another factor to making your own glazes is that it gives you greater control over the final outcome by allowing for greater experimentation and opportunity to broaden your glaze palette. Once you become more familiar with the process, you will soon be able to build on your knowledge and gain confidence as you go along.

BUILDING A GLAZE IDENTITY

The development of a signature glaze colour, effect or style can involve a lot of hard work and patience to fully resolve, but the process of investigation is an extremely enjoyable and rewarding activity that firmly underpins an evolving ceramic practice. There are a number of important factors to consider before you embark on your glaze journey, all of which are instrumental to the final conclusion of your chosen aesthetic. These include the clay body the piece is made from, type of kiln you have access to (electric, gas or other), firing temperature (for example earth-enware/mid-temperature/stoneware) and whether the piece is intended to be functional, decorative or sculptural/experimental. For example, if your work is made from red terracotta clay, this clay body has a high iron content (4–7 per cent) and typically has a maximum firing range of around 1200°C/2192°F/ cone 5. Above this temperature it could melt and blister, therefore you should aim to work within the confines of its firing range. Perhaps you are making a large sculpture to be located outdoors; the hardy properties of a stoneware clay body and subsequent stoneware firing temperature of 1260°C+/2300°F/ cone 8+ will determine your glaze choice. Likewise, if you are making porcelain tableware and enjoy the qualities of traditional celadon and tenmoku glaze, then you ideally need access to a reduction kiln to achieve this result.

Emma Lacey, Everyday mugs (2022). H: 9cm. Stoneware, thrown. Commercial matt glaze coloured with stains and oxides, producing a wonderful variety of different colours and tones.

Once you have these principles in place, you can move forward with your planning. The key to achieving success with glaze is to first really understand exactly what surface finish you are aiming for as this will help you define your pathway and make apt decisions. For example, let’s say you are interested in organic qualities – therefore a place to start might be to experiment with dry, textural glazes and play around with layering the application. This may seem obvious but too often the temptation is to resort to an appealing glaze recipe and apply this to the work without proper consideration for its relevance to the form, suitability, or how it will contribute to the overall success of the piece. When so much time has been invested in the making of a piece, equal time and thought should be given to its resolution. Glaze should never be an afterthought or done on a whim, otherwise the risk of failure or a poor outcome will increase significantly. Here are some useful tips and information to help you develop this area of practice:

Initial research

To establish a successful glaze aesthetic, it can be helpful to reflect on the creative motivations that drive your work, with the aim to forge a link between the form and surface. You might already have a clear vision for your work and therefore it is a case of investigating suitable glazes that fit your criteria. However, if you are unsure where to begin, there are a number of ways to prompt ideas. In particular, sources of inspiration for surface qualities can be found all around you, from the natural world, landscapes, art, history, textiles or fashion, to name a few. You may prefer a traditional approach to glaze development or be completely experimental. Another area of interest could be to emulate real objects through glaze, playing on hyper-realism effects. Expand your influences further by visiting museums, galleries or places of interest. Research the work of other potters, artists, historical and contemporary – what draws you to their work? What can you learn from their techniques and methods? This process of investigation and research will help ground your work and enable you to achieve a strong approach that is unique to you.

Visual material

A sketchbook or notebook can act as an incredibly valuable record of your thoughts and compilation of ideas. How you curate your sketchbook is completely up to you; it could be a very personal resource with notes and annotations, including pages of drawings and rough sketches. This could be further supported with samples or images that capture your interest. A sketchbook doesn’t even have to be a physical resource – you may prefer to keep a digital record, using a tablet device to collate your ideas, or engage with an online mood board such as Pinterest, allowing for social interaction with others. Whatever your preference, continue to gather everything that inspires you into one place so you can access and refer to it as your practice develops. Many artists have a seamless interplay between their two-dimensional and three-dimensional creative work. Specifically drawing and painting can feed into the glaze application, leading to a strong connection between the two. The same can be said for photography – allowing you to focus on points of interest, taking influence from textures, colours and capturing the ambience which can be interpreted into distinctive glaze qualities.