5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Harmakis Edizioni

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Ancient Egypt has left tangible and incisive signs of its religion through monuments and writings. Temples abound with bas-relief and all-round images, painted in bright colors, complete with captions and inscriptions. The royal and noble tombs are no less and they are the ones that have handed down to us figures and texts of great craftsmanship finesse. Funerary and magical writings are unique examples of miniaturistic graphics of divine entities and descriptions of the afterlife. From the observation of these testimonies, an infinite number of divinities emerge, principal, secondary, demons and demigods. This crowd of anthropomorphic entities, but often zoomorphic or a mixture of various human and animal parts, left the first Egyptologists disoriented, giving rise to a conglomeration of hypotheses, sometimes distorted interpretations, and literary duels of various kinds.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

PIETRO TESTA

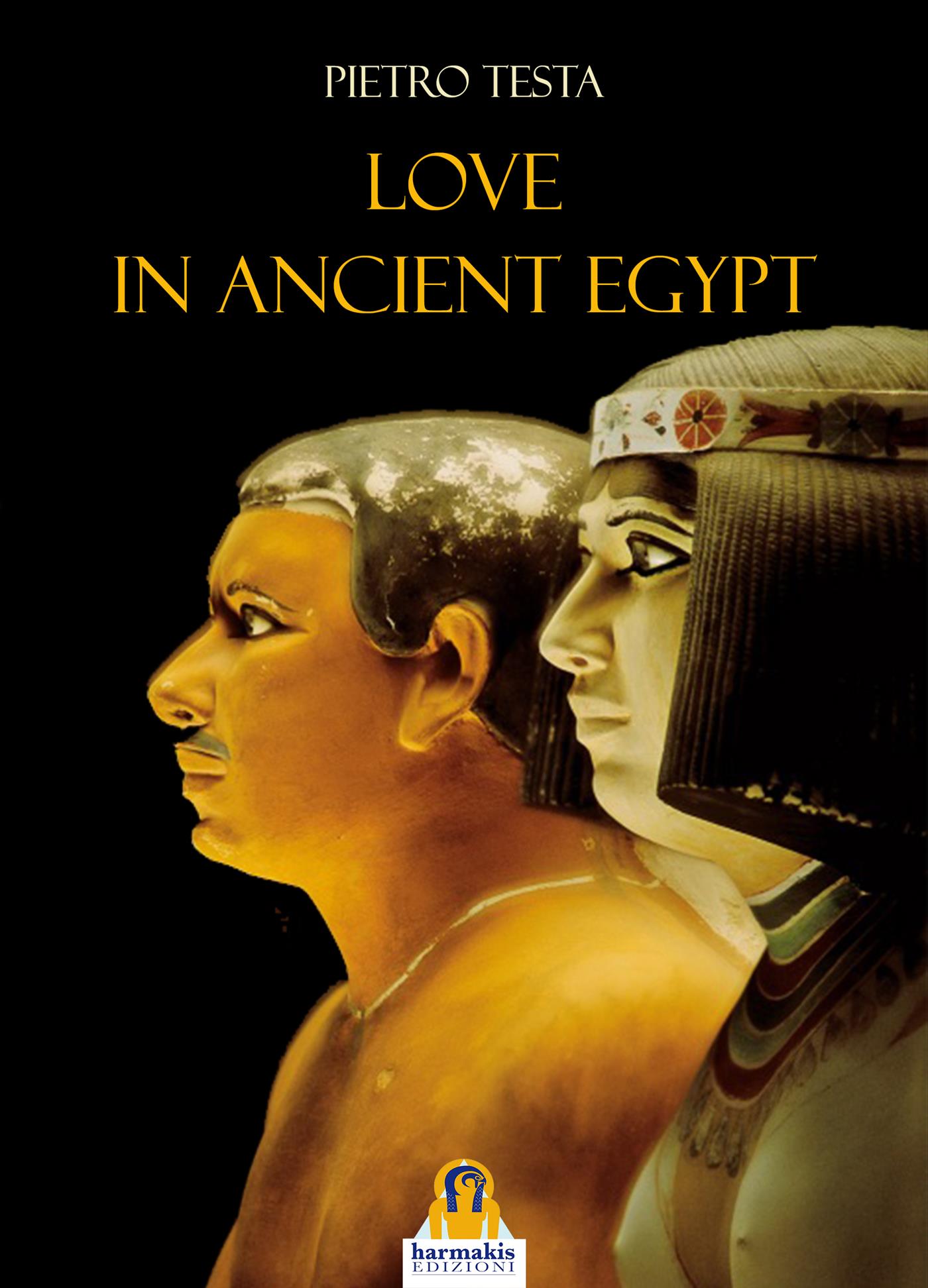

Gods and demigods of ancient Egypt

© All rights reserved to Harmakis Edizioni

S.E.A. Division Advanced Publishing Services,

Registered office in Via Volga, 44 - 52025 Montevarchi (AR)

Operating Office, the same as mentioned above.

Editorial Director Paola Agnolucci

www.harmakisedizioni.org

The facts and opinions reported in this book only bind the author.

Various information may be published in the Work, however in the public domain, unless otherwise specified.

ISBN: 9788831427319

© 2020

© Layout: Leonardo Paolo Lovari

Sometimes there is more wisdom in the

dreams that in the reality of awakening.

Black deer (Hehaka Sapa-1853-1950; Tribe degli Oglala).

PREFACE

Ancient Egypt has left tangible and incisive signs of its ‘religion’ through monuments and writings. Temples abound with bas-relief and all-round images, painted in bright colors, complete with captions and inscriptions. The royal and noble tombs are no less and they are the ones that have handed down to us figures and texts of great craftsmanship finesse. Funerary and magical writings are unique examples of miniaturistic graphics of divine entities and descriptions of the afterlife.

From the observation of these testimonies, an infinite number of divinities emerge, main, secondary, demons, and demigods. This crowd of anthropomorphic entities, but often zoomorphic or a mixture of various human and animal parts, left the first Egyptologists disoriented, giving rise to a conglomeration of hypotheses, sometimes distorted interpretations, and literary duels of various kinds.

There is no denying the exorbitant number of divinities that appears in the eyes of the spectator who can still remain disoriented today. However, this crowd of entities is not the result of unbridled or obtuse imagination, but the result of logical reasoning that has its basis in prehistory. Through the intellectual path of the Egyptian civilization, the memory has become myth and has acquired a complete organization in the arrangement and arrangement of the manifestations of the creator god.

Here we enter a delicate domain that has some points in common with our way of thinking, but which is different from it: speculative thinking.

Speculation is an intuitive way of knowing that transcends experience by trying to explain, unify and coordinate it, thus distinguishing itself from mere idle speculation.

In ancient Egypt, and generally in the peoples of the ancient Middle East, speculation found unlimited possibilities for development, not being restricted to the search for a truth of a scientific nature, and therefore disciplined. There was no clear distinction between nature and human being. The so-called primitive peoples and the ancients considered the human being as a piece belonging to the kingdom of nature: two worlds not opposed and which did not require distinct ways of knowledge. If for us the phenomenal world is above all a ‘what?’, For the ancient it is a ‘You’.

To the primitive, the surrounding world does not appear inanimate, but full of life sparkling from the human being, from the animal, from the plant, from the thunder, from the sun: in short, by the constituents of the kingdom of nature. Faced with a phenomenon, ancient man does not say ‘what is it?’ But says ‘You’: the ‘You’ reveals the individuality, qualities and will of the phenomenon. In this perspective, the phenomenon becomes an experience of one life compared to another, engaging man’s faculties in a mutual relationship.

It happens that each experience of a ‘You’ becomes individual, and these experiences are actions that are configured in narration: this becomes a “myth” in place of analysis and conclusions. The myth was not used to amuse or explain certain phenomena, but to expose certain events in which the very existence of man was engaged, his direct experience of a conflict of hostile and beneficial forces.

The images of the myth are not metaphor but a veil carefully chosen to cover an abstract thought. The images are not separated from thought, since they represent the form in which the experience has become self-conscious.

The ancients, therefore, expressed their emotional thinking in terms of cause and effect, explaining the phenomena in a temporal, spatial and numerical context. The ancients, mind you, knew how to reason logically, otherwise we would not have the great civilizations we know: simply often a purely intellectual attitude was badly suited to the experiences of reality, certainly more significant.

For ancient man, the contrast between reality and appearance had no meaning. This is the case of dreams, held in high regard, and of hybrid and non-hybrid entities, inspired by the doubt of the unknown physical. The same happened for a lack of distinction between the world of the living and the dead, since the dead entered the human reality of anguish, hope and resentment.

There are several dictionaries on the divinities of ancient Egypt (most of them in a foreign language) from the most detailed to the generic ones. My intent would be to give the reader an average detailed picture of the important, secondary deities, demigods and ‘demons’ who populated the fourth dimension of ancient Egypt: all in our Italian language, still (semi) unknown in the field of Egyptology.

I thought it appropriate to report the hieroglyphic names of the deities, inserting the most effective illustrations into the text, with explanatory and bibliographical notes where necessary. Of course, I found it useful to precede the list of entities by a brief introduction on the Egyptian ‘religion’ and some of its phenomena which should help the reader to better understand everything.

Pietro Testa

Naples 2017

CHAPTER 1

NOTES ON THE EGYPTIAN RELIGION

1.1. Generality

The ancient Greek historian Herodotus, who is supposed to have visited Egypt in the fifth century BC, describes the Egyptians as religious to excess more than any other human race. Most of us have the same impression.

Apart from the tombs, the most striking and immanent manifestation of Egyptian architecture is represented by the temples; Egyptian art is dominated by the figures of the gods; the names of many Egyptians honor the gods; and it is difficult to find an Egyptian text that does not mention one or more gods.

However, Herodotus’ statement reflects a particular western notion of religion which (starting from the Greeks) has distinct religions for the various spheres of human existence, such as government, social behavior, intellectual research and science. In ancient Egypt there was no such distinction.

What we call the Egyptian religion is nothing but the way the ancient Egyptians understood their world and related to it. Whether or not they believe in the existence of a god (or gods), many societies today view the world objectively as a set of impersonal elements and forces. We understand, for example, that the wind arises from the difference in high and low pressure areas; people get sick from germs or viruses; things grow and change due to chemical and biological processes. This knowledge is the legacy of centuries of scientific experiments and thoughts. Today it provides us with a detailed understanding of how the world is going and how we must behave in relation to it in order to live better and more comfortably.

The ancient Egyptians faced our own physical universe and, like us, tried to understand it and behave in relation to it. But, without the benefit of our centuries-old experience, they had to seek an explanation of natural phenomena and the means to behave accordingly. The answers they gave are what we call religion.

Where we see impersonal elements and forces acting in the world, the Egyptians saw the will and actions of beings greater than themselves: the gods. For example, not knowing the scientific origin of a disease, they could only imagine that some evil force was in it. Although they could, and did, develop practical remedies for fighting ailments, they also believed that it was necessary first to ward off or pacify the force that had caused the disease. The Egyptian medical texts therefore contain not only detailed descriptions of physical diseases and pharmaceutical prescriptions, but also magic formulas to be used to combat evil forces. What we distinguish between the science of medicine and the religion of magic was the same for the Egyptians,

The gods and goddesses of ancient Egypt are neither more nor less than the elements and forces of the universe. The gods did not control these phenomena, like the Greek god Zeus with lightning: they were the elements and forces of the world.

We express this peculiarity by saying that the gods were immanent in the phenomena of nature. For example, the wind was the god Shu; when an Egyptian felt the wind in his face, he felt that Shu touched him.

As there are hundreds of elements and forces in nature, so there were hundreds of Egyptian gods. The most important, logically, were the major natural phenomena. They included Atum, the original source of all substances, and its offspring: Geb and Nut, the earth and the sky; Shu, the atmosphere; Ra, the sun; Osiris, the male generating power; Isis, the female principle of motherhood. What we would consider abstract principles of human behavior were also gods and goddesses: for example, order and harmony (Maat), disorder and chaos (Seth), creation (Ptah), reason (Thoth) , anger (Sekhmet), love (Hathor).

The power of royalty was also a god (Horus), personified not only by the sun as the dominant force of nature, but also in the person of Pharaoh as the dominant force of human society. Our distinction between religion and government would have been incomprehensible to an ancient Egyptian, for whom royalty was a divine force. As far as the ancient Egyptians could, and did, rebel against kings and even assassinate them, they never replaced the pharaonic system with another method of government. It would have been like replacing the sun with something else.

The Egyptians saw the will and actions of their gods in action in the phenomena of everyday life: Ra, in the daily return of light and heat; Osiris and Isis, in the miracle of birth; Maat or Seth, in the harmony or disorder of human relationships; Ptah and Thoth, in the creation of buildings, art and literature; Horus, in the king whose government was life.

In many cases they saw the presence of the gods even in some species of animals: for example, Horus in the hawk that flies above all living creatures, or Sekhmet in the ferocity and determination of the lion. This association is the key to understanding numerous images of animal-headed gods in Egyptian art. For an Egyptian, the image of a leontocephalous woman, for example, made two things converge into one: first, it was not the image of a woman and referred to a goddess; second, the goddess in question was Sekhmet. These figures were not an attempt to portray how the gods could appear or how they could be seen; on the contrary, they were nothing more than enlarged ideograms.

Since the Egyptians saw the gods in action in all natural and human behaviors, their attempt to explain and treat these behaviors focused on the gods. Egyptian myths are the counterpart of our scientific texts: both explain why the world is like this and why it behaves this way. Hymns, prayers and offering rituals have the same purpose as our factories of genetic engineering and nuclear force: both are an attempt to mediate the effects of natural forces and to use them for the benefit of humanity.

Although the Egyptians admitted natural and social phenomena as separate divine forces, they also realized that many of them were related to each other and could also be understood as different aspects of a single divine force. Realization is expressed in the practice known as syncretism, that is, the combination of several gods in one. For example, the sun cannot be seen only as a physical force of heat and light (Ra), but also as a governing force of nature (Horus), whose appearance at dawn makes life possible, a perception incorporated in the composite god Re-Harakhty (King, Horus of the two horizons). The tendency towards syncretism is visible in all periods of Egyptian history. It explains not only the combination of various Egyptian gods, but also the ease with which the Egyptians accepted foreign deities, such as Baal and Astante, in their pantheon as different forms from their familiar gods.

From the 18th dynasty onwards, Egyptian theologians also began to recognize that all divine forces could be understood as aspects of a single great god, Amon, king of the gods. The name Amon means the hidden. Although his will and actions could be understood as individual phenomena of nature, Amon himself was primarily hidden. Of all the Egyptian gods, Amun only existed outside of nature, since his presence was perceived in all the phenomena of everyday life. The Egyptians expressed this dual character in the composite form Amon-Ra: a god who was hidden, but manifested in the greatest and most natural forces.

Despite this discovery, however, the ancient Egyptians never abandoned their belief in many gods. In this respect, the Egyptian understanding of divinity was similar to the late Christian concept of the Trinity: a belief that a god could have more than one person. As bizarre as the Egyptian gods may seem to the person of today, the religion of ancient Egypt is not very different from other religions more familiar to us. Far from being an isolated phenomenon in human history, the Egyptian religion today stands at the beginning of modern intellectual research and development.

1.2. ba (;;) 1

Since we will often find ourselves in front of the term ba of a divinity, it will be painful to illustrate this concept, valid for the created world.

The ba (bA) is one of the major components of the individual. It is generally translated as ‘soul’ but this term renders the Egyptian concept little.

From a certain point of view, the ba seems to be observed more from the point of view of an observer than of the individual with whom it is associated. This aspect of the ba is incorporated into an abstract term: bau (bAw) which means something like “grandeur”, “effect” or “reputation”.

The king’s actions against the enemies of Egypt or divinity intervention in human affairs are often called bau of their agents.

The ba itself seems to be a characteristic of the human being or of the gods, but the notion of bau is also associated with objects which, as a rule, are inanimate.

Like the soul, the ba does not seem to be physical. However, unlike the soul, it could be understood as a physical way of existence separated from its owner even before death. Any phenomenon in which the presence or action of a god is perceived can be understood as his ba: for example, the sun as the ba of Ra; the bull Apis as the ba of Osiris. In the late period the scriptures are often called ‘bau of Ra’.

A god can also be considered as the ba of another: this particularly concerns Ra and Osiris who every night find themselves together in the afterlife in a union in which Ra receives strength and rebirth and Osiris is resurrected by Ra. The two divine forces are thus occasionally referred to as ‘that of the two ba’.

Like the gods, the king can also be present as ba in another way of existence. The pyramids of the Old Kingdom are often referred to as their owner’s ba: for example, the pyramid of King Nefer-ir-ka-Ra is called ‘the ba of King N.’. Officers also often carry names that identify them as the king’s ba.

1.3. The zoomorphism of divinities in relation to religion

Let’s start from the clarification that the terms’ men; human beings’ (rmT) are to be understood as’ Egyptian humanity ‘. In the tombs of the New Kingdom the whole of humanity, on which the sun god Ra reigns, is divided into ‘Men (rmT), Asians, Nubians and Libyans’. When the Hittites, amazed and heartbroken by the massacre by Ramesses III in Qadesh, shout:2

it is certainly not a human (rmT) who is among them, but Sutekh the great power!

The term rmT could be understood as ‘any Egyptian’: ‘human’ in this case it is ‘Man’ with a capital U.

When a god has a human face, it is said that he has the face of a pat (pat), a term designating the highest social belt of Egyptian society, and it could not be otherwise: a god cannot have the face of a common Egyptian, but that of a ‘patrician’.

The animals are enumerated in detail. Starting in the New Kingdom these beings are listed by size: large livestock, small livestock, birds, fish, insects, etc.

In these lists the term awt, small cattle, indicates goats, rams, swine, donkeys, gazelles and antelopes. Ultimately the word awt acquires the meaning of ‘animals’ and serves to designate the sacred animal, of whatever species it is. So what the animal best symbolizes, for the Egyptian, is essentially part of its more immediate context.

This is how a relationship is created between man and divinity: it can be called “the shepherd protector of his livestock (awt)” or “the human race”. This image evokes the position of men in creation; they are part of creation, that is, animated beings created by the Demiurge. Thus a supernatural force can take any form, animal or human: the latter is one of the other possible ones.

Animated beings are of the same nature and they share the same fate. For example, a cat after it has lived together with its owner, can be buried in a small sarcophagus and be proclaimed ‘venerable with the great god’ and benefit from the same offer formulas as humans.3

When listing ‘men, gods, spirits, the dead’ this does not mean that humans rank first in this hierarchy, but simply that men are turned to supernatural entities.4 The key position of man in inaccessible forces, tangible or not, but which the divine can touch, is explained through various episodes of the myth. In the golden age, the gods and men were one, but then the Demiurge aged and mankind turned against his authority. The gods joined forces and decided to exterminate mankind; the rest of the animated beings were not taken into consideration, since they did not participate in the rebellion. The Creator sent his daughter in the form of a lioness to punish men, as a lion knows.

A new order is being established because the Demiurge separates the earth from the sky, places the moon and the stars there and takes refuge there in the form of the sun with the other gods. If man wants to benefit from the regular return of the seasons, the flood of the Nile, day and night, etc., he must imperatively conform to the Rule (Maat) and worship the divinities.

Around man, animals, within the same species, undifferentiated from one individual to another, unchanging for generations, are like a reminder of that time that was the golden age. According to Frankfort, the nonhuman (superhuman) incapable of change, that is, the animal, is a living symbol of divinity. Plants occupy an ambiguous place in the list of animated beings, perhaps because they were primarily used for feeding.5 After all, plants are above all an instrument, a support of the divine; but they do not have the uniformity of the animals or their freedom of movement.

A god may have the nickname ‘Lotus face’ 6 but this does not mean that a man will be depicted with a lotus flower in place of the face: the expression refers to the meaning of the concept ‘face’ which goes beyond the simple image.

We now enter the concept of face as meaning. The face defines the identification of a human being. When the Demiurge created the gods from his own flesh, he differentiated their faces. The solar disk is the face of the god himself, but it changes brightness during the day and disappears during the night: this is only one aspect among many others. Genes and demons, whose role is to represent the facets of their essence, bear names that describe the nature of their faces. .

The face is a sign that allows man to orient himself towards the divine. It is to him that he addresses his prayers; conversely, it is because the inhabitants of the afterlife adore the sun when it makes its nocturnal journey, that it manifests itself to them as a face. When we qualify a god as ‘the one with the beautiful face’ we refer to the benevolence with which he listens to prayers and supplications. Parts of the face of a divinity, such as ‘the ear that listens’, are responsible for the oracular aspect.

The face of a divinity has an independent existence and seems to have had its own priesthood. The sacred sticks, the necklaces, the poles surmounted by a head, the aegis, are divine emanations.

But the head is not the face. The sun god in Amy-Duat travels with a ram’s head. In funerary texts the head is the name of the funeral mask which gives the deceased two functions: the vision and a new perception of the divine, but also hiding from the dangerous divine forces. The full name of the mask is tpn sStA, head that hides, 7 thanks to which the deceased perhaps assimilates to that aspect of Osiris of which it is said:8

he has the corpse that has no head, the mummy that has no face, the male with the turned up skin.

The funeral mask always has human features and, once transfigured, it could take on any shape, including the animal one, even if the deceased common mortal always hopes to have a human face. Only the king, exceptionally, can take on an animal mask in death.

The animal head is therefore a divine privilege not accessible to ordinary mortals. Divinity, multifaceted by nature, exposes one of its many aspects. The human body is a sign and we will try to distinguish its meaning by examining its antithesis, that is, the animal body.

In ancient times the animal was the bearer of the divine message: an animated and tangible being, an intermediary between man and divinity, not being of independent existence. The Apis bull (Hpw) and the Phoenix (bnw) end up over time with acquiring anthropomorphic form: the first in the XII dynasty, the second towards the end of the Ramesside era. With human body, and keeping animal head, they acquire their independence by becoming gods in all respects: if the animal head reveals an aspect of the nature of the god, his human body is the sign of his individuality.

The anthropocephalic animals, although constituting a variant of the same theme, do not have a symbolic function similar to that of the above scheme. The human-headed bird in which the deceased incarnates wants to mean that he has access to a power beyond his human abilities, and therefore supernatural power: to fly freely, to go up to the sky and reach the sphere of the gods. The sphinx, human-headed lion and the king’s image par excellence, indicates that he possesses the strength of the king of animals.

In any case, the human head on the animal body translates the presence of the human (king or common mortal) into the divine. But this combination depends on the gods among whom the presence of the human is not evident, since it causes (even if apparently) imbalance in the harmony of symbolic relationships.

It can be understood how Osiris, humanly slaughtered, can dispose of a bird-soul (ba); but what about Isis or Hathor represented in this form outside the funerary context? Like the bird, in which the deceased is manifested, so these representations tend to symbolize what in these goddesses is perceptible to man: for example, their solar aspect, female counterpart of the sun visible in the sky.

The function of the human body, a sign of individuality, is replaced by that of the animal body as a sign of a faculty of power: divine for the bird, real power for the lion. It can be understood how the heads can vary respecting the relationship between the animal head and the human body: the sphinx changes its head if it refers to Amon-Ra (aries), or to the guardians of royalty, that is Horus (hawk) and Seth (his animal mythical.