6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Harmakis Edizioni

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

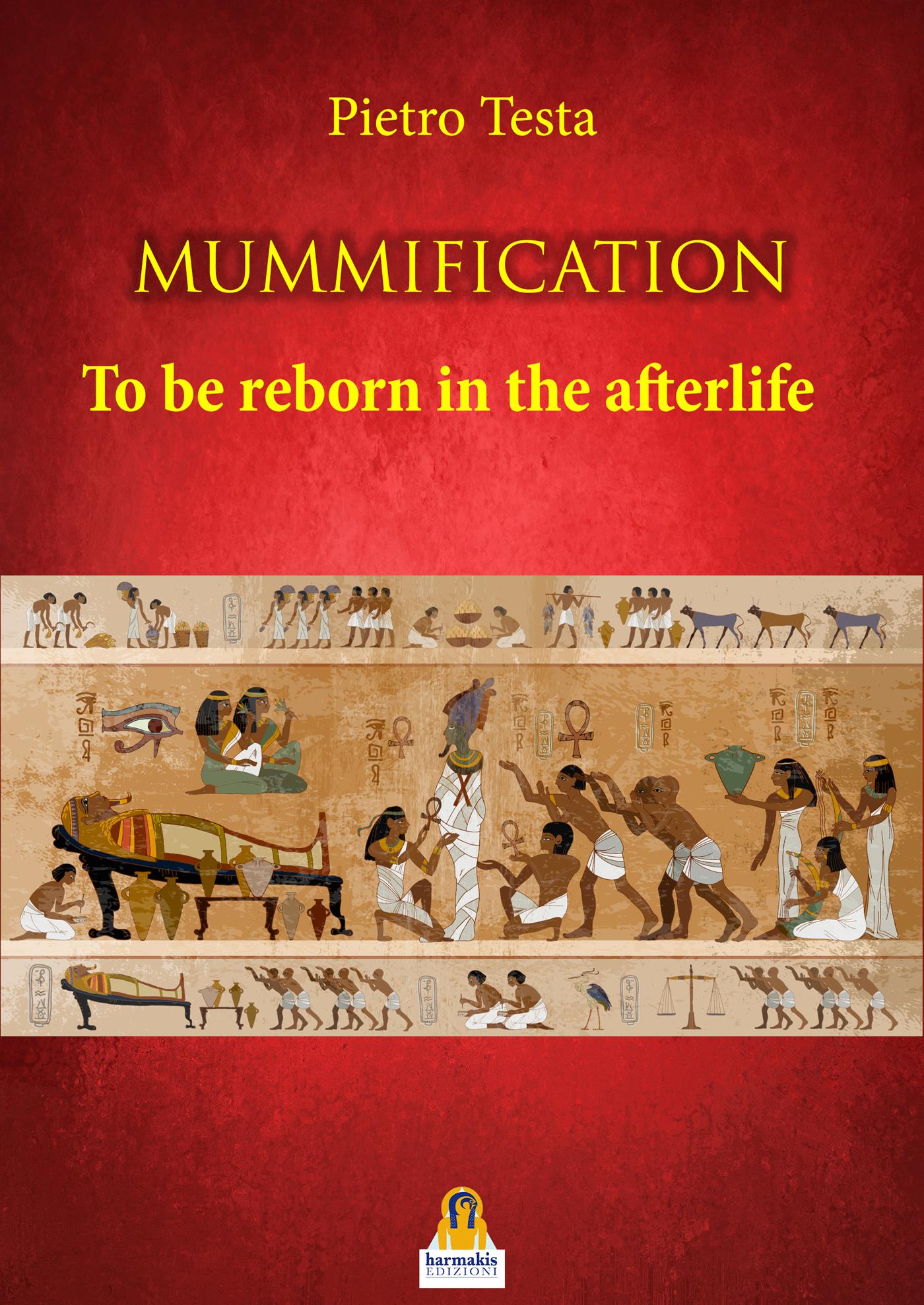

"Ah, Unis! You certainly didn't go dead, but you went alive!" This assertion addressed to the late King Unis of the 6th dynasty is a prelude to the content of this book: funeral rituals in ancient Egypt. The ancient Egyptians, loving life very much, tried to continue it after death. To fulfill this hope, they subtly and logically exploited the concepts of religion and magic based essentially on the myth of Osiris' bloody death and rebirth united with the sun, the principle of light and life on earth and in the afterlife. The historical and cultural memory accompanied the problem of death during the historical arc of Egypt, providing a series of religious speculations of the myths expressed in written and oral canons that characterized the preparation for the journey to the mysterious world of the other life. We realize then that the origin of the mechanism of death and rebirth of the human being starts from the death and rebirth of the gods, from the animation of their painted or plastic images, the receptacle of their heavenly power and strength on earth.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

PIETRO TESTA

MUMMIFICATION

To be reborn in the afterlife

© All rights reserved to Harmakis Edizioni

S.E.A. division Advanced Publishing Services,

Registered office in Via Volga, 44 - 52025 Montevarchi

(AR)

Operating Office, the same as mentioned above.

Editorial Director Paola Agnolucci

www.harmakisedizioni.org -

The facts and opinions reported in this book

exclusively engage the Author.

Various can be published in the Opera

information, however in the public domain, unless otherwise specified.

© 2020

© Layout and graphic elaboration: Paola Agnolucci

ISBN: 9788831427210

Share your knowledge. It’s a

way to achieve immortality.

Dalai Lama

PROEM

“Ah, Unis! You certainly didn’t go dead, but you went alive!” 1

This statement addressed to the late King Unis of the 6th dynasty is a prelude to the contents of this book: funeral rituals in ancient Egypt.

The ancient Egyptians, loving life very much, tried to continue it after death. To fulfill this hope, they subtly and logically exploited the concepts of religion and magic based essentially on the myth of Osiris’ bloody death and rebirth united with the sun, the principle of light and life on earth and in the afterlife.

Religion and magic arose from the careful observation of nature and its intrinsic forces that are not visible, but can be understood by attentive and receptive souls. The prehistoric cultures of the Nile valley laid the foundations for a belief in the continuation of life after death, creating a legacy that was developed and shaped by the needs of the country’s historical and cultural changes, while remaining certain characteristics of phenomenology.

The historical and cultural memory accompanied the problem of death during the historical arc of Egypt, providing a series of religious speculations of the myths expressed in written and oral canons that characterized the preparation for the journey into the mysterious world of the other life. We then realize that the origin of the mechanism of death and rebirth of the human being starts from the death and rebirth of the gods, from the animation of their painted or plastic images, receptacles of their heavenly power and strength on earth.

The myth of Osiris bequeaths the concept of preserving the corpse in the form of incorruptible matter by mummification process accompanied by the protection of magic, understood as a natural force existing since Creation. The incorruptible corpse is thus made ‘noble’ and must be vitalized in its organs: it is necessary to give it life and energy to put it back in harmony with its ka, its ba and its akh. The animation, the breath of life given to the divine statues is also transferred to the mummy which is also a ‘statue’, a ‘simulacrum’ of the living era: we thus have the ritual of the Opening of the Mouth, naturally connected also to the Mysteries of Osiris .

This gear that becomes more and more complex with the passage of time, especially in the late epoch and under Roman domination, has its place in a tomb, an image of the house of the living, equipped with figurative presences and writings animated magically and eternally by the ‘voice just ‘(appropriate) of the ritualist priest, and specialized in the pronunciation of the ethereal vibrations present in the images and in the hieroglyphic writing, which however is image.

We could be perplexed before these testimonies of a millenary culture like that of the people of ancient Egypt, but we should not forget that it was precisely this civilization (with its strengths and weaknesses) that left a culture of thought that influenced the Greeks , and whose filaments came and settled in the Roman Empire, with echoes in Christian culture.

The reader who will have the good fortune to read the pages of this book should for a moment abandon today’s mentality and let himself go to that of ancient Egypt, accepting the way of understanding the life of this people as news and cultural (and spiritual) enrichment. and his legacy.

The hieroglyphic texts are performed with the JSesh software provided FREE online by Serge Rosmorduc. I have not reported the transliteration of the documents (except in some cases), preferring only their translation for practical reasons of the reader, apart from the explanatory notes, the excursus and the annexes.

Happy travels in the rituals of ancient Egypt!

Pietro Testa

Naples 2019

CHAPTER 1

Notes on the Egyptian religion

1.1. The world before creation

Egyptian texts frequently refer to the gods and events involved in creating the world. There are many different explanations for the creation, and most of them were associated with the worship of a particular god in one of the major cities of ancient Egypt. Egyptologists believed that these accounts represented competing theologies with each other and, to a certain extent, this is true. In recent years, however, scholars have begun to recognize that the various accounts of creation were less confused than the different aspects of a single, uniform account of how the world was created. onfusi dei diversi aspetti di un singolo e uniforme racconto su come il mondo fu creato.

In Egyptian creation was called rk nTr, the time of god, or more specificallyrk ra, the time of Ra, but alsork nTrw, the time of the gods. This reflects the Egyptian concept that the creation was the work of both one creator and other gods: it was a joint effort of all the forces and elements of the universe.

Before the world was created, the universe was an unlimited ocean whose waters were scattered in infinity and in all directions. The Egyptians called this ocean nw(y), the aqueous medium. Like the other elements of the universe, it was a god (Nu, later Nun) who is often calledit(i) nTrw, father of the gods, in recognition of his priority.

Even if no one ever saw this universal ocean, its characteristics could be imagined in contrast to the created world.

It was water (nwy), while the world contained dry earth and air. Where the created world was active, it was inert (n(i)n(y),origin of the later name Nun). It was an infinite expanse of water (HHw) where the earth of the world was defined. While the world was illuminated by the sun, this ocean lay in perpetual darkness (kkw). And, in contrast to the tangible and knowable world, it was hidden ( imn) and confused ( tnm).

Like the waters themselves, these qualities were considered divine by right, male deities because such are their names. Some of them are mentioned in the very first religious texts dating back to the end of the Old Kingdom. Since the waters were an integral part of the creation, the qualities of the waters could also be considered as creator gods.

In early Intermediate and Middle Kingdom texts, we meet four of these entities in this role:

wateriness (nwy)

Infinity (HHw)

Darkness (kkw)

Confusion (tnm).

Since the Egyptians associated birth with creation, male qualities had female counterparts. From the Late Period, the group was made up of four couples, usually:

Nu (o Nun) e Naunet, representing aqueousness and inertia (niny)

Huh e Hauhet, infinity

Kuk e Kauket, the darkness.

Amun e Amaunet, the occult.

The eight gods were worshiped as xmnyw, the Ogdoade (a Greek word meaning group of eight). They are often represented with frog heads (male) and snakes (female), two species of animals that the Egyptians associated with creative waters. Theology and adoration of the Ogdoade concentrated in the city of Hermu polis which was called xmnw, City of Eight, in their honor. This name, pronounced in Coptic , survived in the modern Arabic name el-Ashmunên.

The myths that focus on the role of the Ogdoade in creation are known as the Hermopolitan system. Most of what we know of this theology comes from texts from the Ptolemaic Period.

In older texts the gods were simply mentioned by their name. However, although antecedent reports of the Hermopolitan system are lacking, it is probable that the theology encountered in the Ptolemaic texts already existed in the Old Kingdom, since the name xmnw, City of Eight, given the 5th Dynasty.

In one of the later texts, the Ogdoade is described as father and mother of the solar disk who came to his presence on the high hill from which the solar lotus arose. This refers to one of the most ancient Egyptian images of creation: a hillock that emerged as the first dry land when the primordial waters retreated. We try to see in this image the thought of the first Egyptian farmers who observed the hills of land emerging from the withdrawal of the waters of the annual flood. Just as the flooding of the Nile left the land fertile and ready to grow new plants, so too universal waters produced new life on the primordial hill, in the form of a lotus plant from whose flower the sun emerged on the world for the first time to give light after dark.

The Egyptians worshiped this first lotus plant as the god Nefertum (nfr-tm). The same primordial hill, honored as the first place in the world, was the form of the godo Ta-cenen (tA-Tnn(y),lett. land that becomes distinct ). Many temples Egyptians had in their sanctuary a hillock of earth that not only commemorated the primordial hillock, but was also intended as a primordial hillock. Like the creation tales themselves, these hillocks did not compete with each other in recognition of the primordial hill, but were seen as alternative, complementary realizations of the first place.

The image of the primordial hill is not only preserved in the texts of creation, but also in hieroglyphics. The word appear is always written with the sign bilitter representing the sun’s rays appearing on a hillock. In the first hieroglyphics this sign has the form, where the image is clearer and more expressive.

1.2. The Gods

The ancient Greek historian Herodotus, who is supposed to have visited Egypt in the fifth century BC, describes the Egyptians as more religious than any other human race. Most of us have the same impression. Apart from the tombs, the most vivid and immanent manifestation of Egyptian architecture is represented by temples; Egyptian art is dominated by the figures of the gods; the names of many Egyptians honor the gods; and it is difficult to find an Egyptian text that does not mention one or more deities.

Herodotus’ assertion that the Egyptians were religious to excess, however, reflects a particular western notion of religion which (starting with the Greeks) has distinct beliefs for the various spheres of human existence, such as government, social behavior, research intellectual and science.

In ancient Egypt there was no such distinction. What we call the Egyptian religion is nothing but the way the ancient Egyptians understand their world and relate to it. In Egyptian writing there is no vocabulary translatable with religion, nor with faith or devotion. However, there are a series of terms to designate the offering and all the objects and acts connected to it, or the clergy. The word adoration, as an expression of man-divinity relationship, appears in many forms; the prayer is then expressed in various ways without being distinguished from praise, a similar word as resulted from the shape of the sign.

In ancient Egypt there was no such distinction. From this we deduce that religion in Egypt had a very different structure from that which had become familiar to us with Christian examples. For the predominance of the cult, the Egyptian one is characterized by elements such as the offering and the priest, thus falling within the context of the ancient pagan religions to which the revealed religions are opposed, such as the Christian, the Jewish and the Islamic with the their God who speaks and orders, and with the relative sacred texts of paramount importance.

Conceptually undefined, in the Egyptian religion these phenomena are inconspicuous or, as in the case of prayer, they are closely connected with the ritual formulas.

The Egyptian cult, however, did not derive from duties towards the divinity imposed by the statesman: it reveals, with its available means, the nature and works of the divinity also to each individual of the community. Ethical problems lead the Egyptian towards the divine lord of justice who can grant or deny the grace of knowledge and judge. Theological thought itself meets the needs of the devotee eager to be enveloped by the maximum power of the god.

The ancient Egyptians faced our own physical universe and, like us, tried to understand it and behave in relation to it. But, without the benefit of our centuries-old experience, they had to seek an explanation of natural phenomena and the means to behave accordingly.

Where we see impersonal elements and forces acting in the world, the Egyptians saw the will and actions of beings greater than themselves: the gods. For example, not knowing the scientific origin of a disease, they could only imagine that some evil force was in it. Although they could, and did, develop practical remedies for fighting ailments, they believed that it was necessary in the first place to ward off or pacify the force that had caused the disease. The Egyptian medical texts therefore contain not only detailed descriptions of physical diseases and pharmaceutical prescriptions, but also magic formulas to be used to combat evil forces. What we distinguish between the science of medicine and the religion of magic was the same for the Egyptians.

The gods and goddesses of ancient Egypt are neither more nor less than the elements and forces of the universe. The gods did not control these phenomena, like the Greek god Zeus with lightning: they were the elements and forces of the world. We express this peculiarity by saying that the gods were immanent in the phenomena of nature. For example, the wind was the god Shu: when an Egyptian felt the wind on his face, he perceived that Shu touched him. As there are hundreds of elements and forces in nature, so there were hundreds of Egyptian gods: the most important, logically, were the major natural phenomena. They included Atum, the original source of all substances, and its offspring: Geb and Nut, the earth and the sky; Shu, the atmosphere; Ra, the sun; Osiris, the male generating power; Isis, the female principle of motherhood.

What we consider human behavior to be abstract principles, for the Nilotic were also gods and goddesses: for example, order and harmony (Maat), disorder and chaos (Seth), creation (Ptah), reason (Thoth), anger (Sekhmet), love (Hathor). The power of royalty was also a god (Horus), personified not only by the sun as the dominant force of nature, but also in the person of Pharaoh as the ruling force over human society. Our distinction between religion and government would have been incomprehensible to an ancient Egyptian, for whom royalty was a divine force.

As much as the ancient Egyptians could, and did, rebel against kings or even assassinate them, they never replaced the pharaonic system with another method of government: it would have been like replacing the sun with something else.

The Egyptians saw the will and behaviors of their divinities in the action of the phenomena of everyday life: Ra, in the daily return of light and heat; Osiris and Isis, in the miracle of birth; Maat or Seth, in the harmony or disorder of human relationships; Ptah and Thoth, in the creation of buildings, art and literature; Horus, in the king whose government was life.

In many cases they saw the presence of the gods even in some species of animals: for example, Horus in the hawk that flies over all living creatures; Sekhmet in ferocity and determination of the lioness. This association is the key to reading numerous images of animal-headed gods in Egyptian art. For an Egyptian, for example, the image of a leontocephalous woman converged two things into one: first, it was not the image of a woman and referred to a goddess; second, the goddess in question was Sekhmet.

These images were not an attempt to portray how the gods could appear or be seen; on the contrary, they were nothing more than enlarged ideograms. Since the Egyptians saw the gods in action in all natural and human behaviors, their attempt to explain and treat these behaviors focused on the gods. Egyptian myths are the counterpart of our scientific texts: both explain why the world is like this and why it behaves this way. Hymns, prayers and offering rituals have the same purpose as our factories of genetic engineering and nuclear force: both are an attempt to mediate the effects of natural forces and to use them for the benefit of humanity.

Although the Egyptians admitted natural and social phenomena as possibly divine separate, they realized that many of them were related to each other and could also be understood as different aspects of a single divine force. Realization is expressed in the practice known as syncretism, that is, the combination of several gods in one. Realization is expressed in the practice known as syncretism, that is, the combination of several gods in one. For example, the sun cannot be seen only as a physical force of heat and light (Ra), but also as a governing force of nature (Horus), whose appearance at dawn from Akhet (currently made with horizon) makes possible the whole life, a perception embodied in the composite god Ra-Harakhty (Ra-Horus of the two Akhets).

The tendency towards syncretism is visible in all periods of Egyptian history. It explains not only the combination of various Egyptian gods but also the ease with which the Egyptians accepted foreign gods, such as Baal and Astarte, in their pantheon as different forms from their familiar gods.

From the 18th dynasty onwards, Egyptian theologians also began to recognize that all divine forces could be understood as aspects of a single great god, Amun, king of the gods. The name Amon means the hidden: of all the Egyptian gods only Amon existed outside of nature, since its presence was perceived in all the phenomena of everyday life. The Egyptians expressed this dual character in the composite form Amon-Ra: a god who was hidden, but manifested in the greatest and most natural forces.

Despite this discovery, however, the ancient Egyptians never abandoned their belief in many gods. In this respect, the Egyptian understanding of divinity was similar to the late Christian concept of the Trinity: a belief that a god could have more than one person.

As bizarre as the Egyptian gods may seem to us, the religion of ancient Egypt is not very different from other religions more familiar to us. Far from being an isolated phenomenon in human history, the Egyptian religion today stands at the beginning of modern research and intellectual development.

1.3. The constitutive principles of man

The ancient Egyptians had developed very specific concepts about human nature. For each human being (including the king) it was believed that five different elements were needed to exist. References to these elements occur in Egyptian texts of any kind. To understand what many texts talk about, we need to understand what the Egyptians thought of the five elements and their function in human life.

a) the body (Ha).

The easiest element for us to understand is the physical part: the body is the envelope in which every human being exists. The Egyptians knew that the body was descended from individual parents, from the father’s seed placed in the mother’s womb. They also understood that the body consisted of various parts; for this reason, the plural Haw, which means something like limbs, was often used for the singular word body.

b) the heart (ib).

It was the most important part of the body. For the Egyptians, this was not only the center of physical activity but also the place of thought and emotion (the Egyptians do not seem to have understood the function of the brain) 2. This is a common human belief; we still have his reminiscences in phrases such as, for example, broken heart or best wishes. In Egyptian texts where the word ib is used, the translation mind, spirit, soul, sometimes has a more appropriate meaning than the literal heart. In Egyptian texts where the word ib is used, the translation mind, spirit, soul, sometimes has a more appropriate meaning than the literal heart.

The Egyptian also used the word HAtyto refer to the heart as a physical organ, (a nisbe derived fromHAt, front: i.e. the frontal organ) rather than ib; however, the two terms often seem to be interchangeable.

c) the shadow (Swt).

Shadow is an essential addition to the body that creates it. Since the shadow is generated by the body, the Egyptians believed that it had something of this and, therefore, of its owner. Sometimes the representations of the gods are called their shadows for the same reason.

d) the ba (bA).

This is perhaps the most difficult concept to understand. Essentially, the ba is all that makes a person individual, except for the body. The ba also refers to the impression that an individual makes on others, something like our concept of personality; this notion is subjected to the abstract name bAw(usually written, a false plural) which means something like grandeur; solemnity.

Like the western notion of soul (with which ba is sometimes translated bA), ba is a more spiritual than physical principle, and is the part of a person who lives after the body dies. The Egyptians imagined it as an entity capable of moving freely from the mummified body, outside the grave and in the world of the living; for this reason, it is sometimes represented, and written, like an anthropocephalic bird ().

The concept of the ba is associated above all with humans and gods; but even something, like a door, could have a ba. This is presumable because such objects can have a distinct personality or create a distinct impression, even if they are not alive in the same way as humans and gods.3

e) the ka (kA).

This concept means something like life force. Ka is what makes the difference between a living person and a dead person: death occurs when it leaves the body. The Egyptians believed that the life force of ka appeared with the Creator, was transmitted to humanity in general through the king, and transferred to individual humans by their fathers. The notion of this transfer was sometimes metaphorically represented as a hug; this seems to be the origin of the sign of the outstretched arms with which the word ka is written in hieroglyph. The Egyptians also believed that ka sustained itself with food and drink, since without these substances the human being dies. This notion is expressed under the abstract name kAw (written as a false plural) which means something like energy, specifically that present in food and drink. This is also connected to the custom of presenting offers of food and drinks to the deceased.

The Egyptians were aware that these offerings were not physically consumed by the deceased; therefore what was presented was not the food itself, but the energy (kAw) inside the food that the spirit of the deceased could use. In life, when a person was given something to eat or drink, this was often expressed in the words n kA.k, for your ka.

Only humans and gods seem to have had a ka; even though animals were considered living beings, it is not known if the Egyptians believed that they had a ka. Like the ba, the ka was a spiritual entity and could not be depicted. However, to represent ka, the Egyptians used a second twin image of the individual; for this reason, the word kA is sometimes translated as double.4

f) the name (rn).

For the Egyptians, names were far more important than they are in our society. It was believed that they were an integral part of their owners, as a necessary means for the existence of the other four elements. This is the reason why the Egyptians who could afford to spend a lot of economic resources, ensured their names the condition of survival in their tombs and on their monuments. A name could be erased in life, as well as on a monument or in the sepulcher (damnatio memoriae).

The Egyptians considered each of these five elements to be an integral part of each individual, and thought that no human being could exist without them. This explains, in part, why body mummification was considered necessary for the afterlife. Each element was also thought to contain something of its owner. This was especially true of the name; the mention of an individual’s name could recall the representation of that person, even if he no longer lived.

Writing the name of a person on a statue or near an engraved image represented the possibility of identifying the image with that individual, and therefore providing the person with a physical and alternative form as well as the body. This is the reason for the presence of statues and reliefs in Egyptian tombs; for the same reasoning, the Egyptians more often wanted to place their statues in temples, so that they could be forever near, or in the presence of the god. At the same time, writing a person’s name on a small clay statue and then smashing it meant, and was considered, an effective means of destroying the owner’s name (rites d’envoûtement).

The identification of a name with its owner was so strong that the same names were treated like a person. In fact, it is often more significant to translate the word rn with identity than with name. Knowing a person’s name was the same as knowing it. .

The infinite power of the Word gives the name the very essence of a person or an object. To name something is to create it, so to pronounce the name of an individual means to make it live in a permanent creation, for better or for worse. Including the name of a person in an evil context, or eliminating the name from a monument, meant destroying the individual bringing him to the condition of non-existence, the worst thing that could happen to an Egyptian. This misfortune had the name of second death, whose only defense was the litany in which it is repeatedly specified that Tizio’s name will live eternally. To increase the possibility of the deceased’s eternal existence, he is made to assume the identity of a god, including his name.

g) akh

The term Ax it is currently translated as "spirit". Etymologically it equates to "glorious", "shining", "effective": the term can be understood as "transfigured part of the divine in the human". Originally the akh was attributed only to the deities and consequently also to the king and later to ordinary mortals. We take into account that Axw means “magic power”; “Power / power” of a god; “Magic formulas; rituals; prayers”; “quality; virtues ”of a man. So akh represents the high radiance of spiritual principles. 5

It seems legitimate to underline that the translation of these terms is always relative, being part of a cultural and religious heritage very far from us and belonging to a dead language.

CHAPTER 2

DEATH AND THE AFTERLIFE

2.1. The death

For the Egyptians, death was not a weak, inert and powerless state of the body. Death was a physical and tangible entity that could be described and expected and, as such, could take on the appearance of an envoy of the deities. This depended on the type of death that the individual caught: illness, accident, murder, etc. Paraphrasing a passage from Ani’s maxims, death, or the messenger who carries it, could arrive at any moment and took the child as the elderly: when it arrived, it could not be said that it was not the time, since it did not look in face anyone. So death is a well-identified someone.

Given the unpredictability of death, one had to be prepared for this event. For the Egyptians, being ready meant (for those who could afford it) preparing a tomb already alive, in which the mummified corpse continued to live. The tombs were located in the necropolises on the edge of the desert, west of the inhabited centers, since every day the sun (Ra) set there (= died).

The Egyptian tombs consisted of two areas. The body was buried with his grave goods in a burial chamber below ground level; this room was sealed after the funeral and was supposed to be inaccessible from then on. On the ground level there was a chapel (or, in the case of royal tombs, an entire temple): offerings and prayers for the deceased could be made in it. Usually the chapel was decorated with images of the past and scenes of personnel carrying offerings, and could have consisted of several rooms. The focal point was usually a niche in the western wall known as a false door, with a slab of offerings placed in front of it. Through this niche the spirit of the deceased could emerge from the sepulchral chamber to take part in the nourishment (kAw) contained in the offerings.

The images were a guarantee of eternity and fixity of what they represented.

However, it must be said that the Egyptians felt, like the rest of humanity, the fear of the unknown and the uncertainty of death, trying to exorcise it and not always believing in ways to avert it. This depends on the various stages of their civilization in harmony with the realistic view of life and earthly existence.

The procedure of what seemed useful and necessary to the human personality and indispensable for the maintenance of life beyond death, led to the well-known practices for the preservation of the body and the construction of the tombs, the ‘houses of eternity’. But at the same time the same ones who had worked for beliefs and insights on survival, often expressed amazement, doubts and bitter skepticism regarding funeral customs. There are several examples, including the well-known ‘Harpist song’ .

The doubts about the effectiveness of the funeral mechanisms became stronger over time, so much so that in the Lower Age we have texts that report the deceased’s crying over his state, especially the silent solitary despair of the children kidnapped from death.6 These fears were right in the earthly life that the Egyptian loved, and for it mummified the body considered indispensable element for the survival of the ba and ka. The akh followed another path because, as we mentioned earlier, it represented the pure spiritual condition that participated in the most abstract happiness. The akh was the late ‘noble’ as opposed to the ‘common’: however both are forms of survival. Although the former depended on the social status of the deceased and on his life conduct, and therefore more powerful, there was nothing to detract from the fact that the akhus in general could be both helpful and spiteful and vindictive, comparable to the afarit of today’s Egyptian folklore.

What Herodotus told us about the obsession with death in the lives of the Egyptians is incorrect. Precisely because the Egyptian people loved life intensely, it deeply felt death. The Egyptians did not take refuge in apathy or inactive mysticism, but they worked and lived to annihilate the effects of death, they prepared an eternal house to live in comfortably and while waiting they enjoyed what they could take advantage of.

The Egyptian has a dynamic attitude towards death: this does not break him down, rather he stimulates him to react with all the means he can devise. If we think that the construction of a tomb, the sarcophagus and the funeral set-up had to cost quite a lot, the Egyptian spent a good part of his economic resources for this purpose, and willingly.

Ultimately, the aspiration of the Egyptians was not in the transcendent, but they tried to make the imagination immanent and translate it into a scenario that, whether living or dead, was part of a tangible experience.

2.2. The afterlife

In ancient Egypt we also find the dead alongside men and gods. The gods, on earth, entered simulacra made of precious materials, or manifested themselves in animals, and dwelled in their houses, the temples that, placed in the center of the city, participated the inhabitants of their presence.

As mentioned above, the cities of the dead were instead located far from the Nile, on the edge of the arid desert. Here the deceased continued to live, being mummified, he underwent the ritual of the Opening of the Mouth that made the breath vital: a living corpse.

If it is strange for us to think that a dead man lived, we must remember, however, that for the Egyptians negative concepts were also positive. Even if there is no denying the existence of nothing, this way of being is only different. Explaining us better, the deceased lived in the afterlife doing the opposite of what he did when he was alive, precisely because his condition was reversed and that could not be assimilated to the earthly one, even if in the end he aspired to it. In the Book of the Dead there are many formulas that protect the deceased from walking upside down, from eating dung and drinking urine, and other things that are contrary to the world of the living; in a protective spell for the son, the mother claims that honey is sweet for the living, but bitter for the dead .7

To overcome the dangers of the afterlife, the deceased was equipped with a set of magic formulas written on the walls of the funeral chamber in the Old Kingdom (Pyramids Texts), on the sides of sarcophagi and coffins in the Middle Kingdom (Texts of the Sarcophagi) and on a papyrus scroll (Book of the Dead, New Kingdom).

The question, however, is that as the time goes by in Egyptian thought the afterlife becomes increasingly lugubrious. The terror of death often cracks the beauty of an afterlife painted in the tombs. The more you go on in time, the more the texts describe an undesirable afterlife in which the deceased lies covered in dust, burnt with thirst, without being able to eat, without being able to make love and without the affection of relatives and friends.

Let’s not forget the afterlife of people who had behaved badly on earth. The texts do not remember him often, precisely because of the exorcistic attitude that the Egyptians had towards unpleasant matters. But we also have figurative evidence in the tombs of the kings in the Theban necropolis that show us truculent tortures and torments endured by evil humanity.

This suggests that the afterlife was also dangerous and for this reason it was necessary to know the topography of this unpredictable world: one of the oldest books is The Book of the Two Ways, often drawn on the bottom of the coffins of the Middle Kingdom. It consists of two paths, one positive and the other negative with a series of indications and formulas so that the deceased could follow the one best suited to his destiny. However the news that the Egyptians give us is not very homogeneous. Depictions of a lush Eden, with wheat and flax with very high stems, trees overflowing with fruit, against documents that tell us that the afterlife is arid and perpetually dark.

In fact, initially the other world was imagined in the stellar immensities and then gradually descended towards the earth, until it was under ground, devoid of the vision of the sun that only in its journey illuminates the various areas. In the New Kingdom, the otherworldly topography of a world made of caves and caves divided by doors is affirmed: we have the Book of Caves, Doors and Duat,8 that describe the spaces littered with dead people who come out of their lairs to acclaim the Sun during its nocturnal journey. They are books painted on the walls of the funeral chambers of the royal tomb, reflecting its structure, and in which the sarcophagus of the sovereign was located at the point where Ra was identified with Osiris.

Over time, the way to reach a good afterlife is refined and soon the idea of another pleasant world for people who behaved well on earth is configured; for the evil ones a hellish life was foreseen that annihilated them forever. Although several magic formulas had been invented to protect the bad guys from the afterlife, a conduct according to specific moral rules to achieve a happy destiny after death is increasingly affirmed: this affirmation of moral values over those of magic is accomplished in late epoch, in the first millennium BC.

CHAPTER 3

The House of Life

pr-anx, House of Life: an institution little known in the current culture of those interested in ancient Egypt. Yet, as we will see, it was a foundation of extreme importance for the elaboration of the various facets of the religious and magical culture of Egypt. 9

Wb10 translates the term as “place of teaching of the scribes” while the Meeks t 11 reports “archives; library; scriptorium “. These three meanings summarize the main functions of the institution.

According to existing documents, the House of Life already exists in the Old Kingdom in the 6th dynasty and lasts until the end of the Pharaonic civilization. The available sources are not very talkative about what was done in this laboratory and this is also understandable given its nature.

A very interesting document is the Salt 825 papyrus (British Museum No. 10051), the content of which is largely devoted to etiological myths and the rest to magical prescriptions. A long passage of the papyrus informs us about the ideal structure of the House of Life to be built in Abydos. Let’s read it, also because it is almost never reported where the topic is discussed:

(6.5)

ir pr-anx

About 12 to the House of Life

6.6

wnn.f m AbDw qdw sw m 4 Xt iw tA Xt Xnw m nbiw Hbs ir tA 4 pr Hna pA anx

it will be in Abydos. Build it in 4 bodies: the internal body in marsh canes and covered (by them). Regarding the 4 houses together with the (sign of) life,

6.7

ir pA anxy wsir pw ir tA 4 pr Ast nb-Hwt gb nwt iw Ast r wa rit iw nb-Hwt

and with regard to the Living One, he is Osiris. Regarding the 4 houses (they are) Isis, Nephtis, Gheb and Nut. Isis will be on one side, Nephtis will be

6.8

r kt iw Hrw r wat iw DHwty r kt pA 4 qaHw nn gb pw zATw.f nwt pw Hr.

other. Horus will be on one side and Thoth on the other: these are the 4 corners. Gheb is his floor and Nut is his firmament.

6.9

f nTr aA pw imn Htp m-Xnw.f iw tA 4 Xt n br m inr iw.f m idrty iw Xr.f m Say

The great god is the hidden one who rests inside. The 4 bodies outside are made of stone with two cords and its lower part in sand.

6.10

iw pAy.f br ky z-2 m 4 rAw iw wa rsy iw ky mHtt iw ky imntt iw ky iAbtt

Its exterior has 4 doors separately: one is southern, another is northern, another is western, another is eastern.

7.1

wnn.f imn zp-2 wr zp-2 nn rx.f nn mA.f wp mAa itn m sStA.f nA rmT.

It must be very hidden and very large. It should not be known nor should it be looked at, apart from looking at the solar disc its mystery. People

7.2

nty aq r.f mDAty pw ra zSw pr-anx pw nA rmT nty m-Xnw.f fkty Sw

who access it must be Ra’s staff, and the people inside it must be scribes of the House of Life. The fekty priest is Shu.

7.3

pw Hnty Hrw pw nty smA sbiw n it.f wsir zS mDAt nTr DHwty pw

The butcher is Horus who massacres the rioters towards his father Osiris. The scribe of the Book of God is Thoth:

7.4

ntf sAx.f m Xrt nt ra-nb nn mA n sDm WDA-rA HAp Xt rAw iw.w Hr

it is he who performs the glorification rites daily, neither seen nor heard. Healthy mouths and body and mouth secrets, they will look at each other

7.5

r Sad sin nn aq iam r.f nn mA.f sw iw.k Hr.tw wr zp-2 ir mDAwt

from cutting and deleting.13 An Asian cannot enter14 nor will it be able to look at it, otherwise you will truly be turned away

7.6

nty im.f bAw ra pw r rdit anx nTr pn im.w r sxr xftyw.f ir mAty pr anx

who are in it are the Power of Ra to make this god live in them and to overthrow his enemies.

Regarding the staff of the House of Life

7.7

pw nty (m-) Xnw.f Smsw pw nt ra wsir Hr zA zA.f wsir

which is inside, is (made up of) the followers of Ra to protect his son Osiris.

An original drawing in the papyrus shows the scheme of functions of the House of Life. The design is executed according to the three-dimensional representation of the ancient Egyptians, that is, with the vertical projections reversed on the horizontal plane.

In the central space, a mummiform Osiris with a white crown and uas scepter in his hands on 9 arches, a symbol of traditional foreign peoples enemies of Egypt.

Around there is a courtyard in which Nut is above and Gheb below. At the four corners Horus, Thoth, Nephtis and Isis.

The four gates are marked by the signs of the west, north, east and south.

From all this we deduce a prescriptive precision concerning a very delicate magical-religious situation.

The consecration of the various parts of the building, based on the assimilation of the walls, the ceiling and the floor to the divinities of the Osirian cycle, clearly shows the sacred character of the institution. Osiris is the central element, the “living” and his being the son of Ra indicates his “solarization” and subordination to this god.

The radiance of the House of Life is highlighted by the presence of the solar disk that illuminates the execution of the rites, except for the central part covered with branches.

The secrecy that enveloped the institution is highlighted, in addition to the text above, for example by another passage from the same papyrus which deals with a book to be written on the 20th day of the first month of the Flood: the recommendation is that must be disclosed. Those who made it public ran the risk of dying from sudden death or suffocation. The editor himself had to be very careful and the book was to be read only by a scribe whose name was on the House of Life list.

The activities of the House of Life were varied. Theurgy was about the most secret and refined rituals that had to make the macrocosm processes work smoothly and extend their beneficial influence in society.

The communion of the sovereign with the solar entities, as an intermediary of them, was the subject of rites and appropriate ceremonies.

The defense of the king from enemies follows the same technique used against Ra and the evil Apophis: in the “Book to bring down Apophis:” 15 the ways of making images of the Evil One and the related deprecatory formulas y sign.

The staff of the House of Life also practiced natural magic intended to assist people in the various vicissitudes of life. It is assumed that the consecration of amulets and prophylactic magical texts also took place in this place.

Funerary magic was practiced in the institution, as evidenced by a fair amount of documents. It was a wish and a possible certainty that the deceased’s name was pronounced by the staff of the pr-anx, just as food could materialize in its library and offerings come into being in it. In particular, funeral offerings were considered vital for the deceased's ka, and the survival of the name, "identity card" of the individual's personality, was of no less importance.