Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Between 1982 and 1992, the World Sportscar Championship embraced the FIA's Group C regulations, spawning a generation of long-distance racing sports prototypes representing manufacturer teams such as Porsche, Mercedes-Benz, Jaguar, Mazda, Peugeot, Nissan and Toyota, as well as a host of specialists such as Spice and Tiga. Driven by top-line drivers, these cars competed in one of the most exciting epochs in the annals of endurance racing. This book focuses on the cars, drivers and races of the era.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 479

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published in 2025 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

This e-book first published in 2025

© Johnny Tipler 2025

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

For product safety-related questions, contact: [email protected]

ISBN 978 0 7198 4543 7

The right of Johnny Tipler to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Front cover: Derek Bell drives the 2649cc twin KKK turbo Porsche 956 #002 in which he and Jacky Ickx won the 1982 Le Mans 24-Hours.

Back cover: The Sauber Mercedes C9/88 placed 2nd at Le Mans, 1989 with drivers Gianfranco Brancatelli/ Mauro Baldi/Kenny Acheson, here leading the 7th place Mazda 767B of David Kennedy, Pierre Dieudonné and Chris Hodgetts.

Page 2: Mike Wilds enters Druids Hairpin at Brands Hatch in the Kenwood Porsche 956-101 that finished 3rd at Le Mans in 1983: ‘Undoubtedly one of my all-time favourite race cars,’ he says.

Page 3: presented in Shell livery, the works 3.0-litre Porsche 962C #137>009 driven by Hans Stuck won the ADAC Supercup round at Hockenheim in July 1987 as well as several other podiums in ʼ87 and ʼ88, including 2nd at Le Mans.

Cover design by Keith Wootton

CONTENTS

Foreword by Mike Wilds

Preface by Jürgen Barth

Timeline

Introduction

CHAPTER 1 DESIGN AND SPECIFICATION

CHAPTER 2 MAKES AND MANUFACTURERS

CHAPTER 3 PORSCHE PREVAILS 1982–86

CHAPTER 4 JAGUAR JAMBOREE 1986–89

CHAPTER 5 SAUBER SUCCESS 1989–90

CHAPTER 6 JAPANESE EXPANSION 1991–92

CHAPTER 7 PEUGEOT MOPS UP 1992–93

APPENDIX I SPECIFICATION TABLES

APPENDIX II PARTICIPATING MAKES

APPENDIX III ANNUAL RESULTS

Acknowledgements

Index

FOREWORD

First of all, I would like to thank Johnny for asking me to write the Foreword for his brilliant book on the history of the FIA Group C International Sportscar Championship, which must be one of the FIA’s most successful-ever series. I feel very honoured to have been asked.

Mike Wilds participated in Group C from 1982 to 1989, pictured here giving the author tuition on the RML track at Silverstone in a 997 GT3 RS.

In 1982, the FIA introduced a category of sports car racing called Group C, run in two classes – Group C1 and Group C2 – and these two categories were to feature in the World Sportscar Championship.

At the end of 1983, my good friend, racing driver Ray Mallock, of RML (and Clubmans Formula U2 fame), called to inform me that the famous Scottish Le Mans-winning team, Ecurie Ecosse, was being reborn with the intention of competing in the new Group C2 World Championship. Would I be interested in joining the team? It took me nearly a whole millisecond to say ‘Yes, please’!

Ray soon told me that Dorset Racing was selling its De Cadenet DFV-powered chassis (No. ADC78/1) and that Ecurie Ecosse was interested in buying the car, which RML would then convert to the new Group C2 regulations.

The car was completed at the beginning of 1984, and after a couple of test sessions in the UK, the team set off for our first event, the Monza 1,000km. It was held on 27 April on the iconic Italian GP circuit near Milan, with eager drivers David Duffield, Ray Mallock himself, and yours truly. We had a wonderful start to our campaign, finishing 2nd in Group C2 and 8th overall, which was not bad at all for our embryonic little team.

Following retirement in the Silverstone 1,000km on 12 May, the team set off for the Le Mans 24-Hour race to be held on the weekend of 14/15 June. When our Ecurie Ecosse team arrived at the Circuit de la Sarthe, the region of France where the race is held, it was agreed that I would drive the first practice laps. I was asked to take the car out for an initial installation lap to warm the DFV up and check all the systems, followed by some fast, slippery laps.

Having made a pit stop for engineering checks at the end of that initial lap, I set off for some more slippery. The car felt amazing. OK, on that second lap, I wasn’t going flat out in top gear down the 3.7-mile (6km) long Mulsanne Straight, but the car felt so stable and driveable.

So, starting the third lap, I accelerated the car past the start/finish line with the Ford Cosworth V8 DFV behind me, singing up to our fairly low rev limit of 8,000rpm, chosen for longevity in endurance racing. And then I changed up, turning right and slightly uphill to fly under the famous Dunlop Bridge and then down towards the Esses. I was so enjoying this little car as we accelerated out of the Esses towards Tertre Rouge, the right-hander that leads onto the Mulsanne Straight.

Exiting Tertre Rouge, I let the car have its head in all the gears and finally settled down for the long trip towards the daunting Mulsanne ‘kink’ (pre-chicanes), which was about three-quarters of the way along the straight. The Ecosse was flying, and if my memory serves me well, Ray Mallock had worked out the gearing, taking the tyre growth – that’s caused by centrifugal force – into consideration. This increases as the car goes faster, altering the gearing of the car – albeit slightly – while giving more top speed. I was watching the temperature and pressure gauges occasionally – but most of all, I was watching the rev-counter, which was rising… and rising… and rising as I sped along, straight as an arrow.

The Mulsanne Straight is normally a main road – the RN138, or Ligne Droite des Hunaudières as it’s called in French when it is not being used as part of a racetrack – and it has the normal broken white line lane markers down the centre. It is usual for the slower cars to keep to the righthand side of the road with the faster cars running on the left, and the broken white line travels past so quickly that it almost appears as one continuous line.

The rev-counter was now reaching towards its maximum of 8,000rpm in top gear, and the Ecosse was still totally stable. And quite why I thought it necessary I will never know – but I took my hands off the steering wheel and the car continued to head straight and true towards the Mulsanne kink at around 217mph.

I was in my element when suddenly there was a huge bang, and my forward vision almost totally disappeared. As you might imagine, this quickly caught my attention, and if I’m totally honest, it scared me witless! For a moment I froze, not knowing what had gone wrong. The cockpit filled with dust, accompanied by an immense noise like a tornado. It was like sitting in a large, over-inflated balloon that had just burst with an immense change in air pressure.

Not wanting to do anything too dramatic, my foot came off the throttle and was hovering over the brake pedal which I started to press gently. The car began to slow and as the dust settled, I checked on the steering – but all seemed to be OK. As the car slowed further, I began to look around to see where all the noise was coming from and as soon as I glanced to my right, I quickly saw that the driver’s door had completely disappeared!

As the car was now down to below 100mph, I guess, the noise was slightly less dramatic. So, having checked all the controls, I drove back to the pits at a much-reduced speed for a debrief and post-mortem with the team.

We eventually worked out the root of the problem. It had been caused by aerodynamic pressure inside the cockpit, which resulted in it bursting outwards. We eventually managed to retrieve the door from the excellent marshals on the Mulsanne Straight, and it was then refitted – virtually undamaged. However, both doors now had holes drilled in them to relieve the pressure build-up in the cockpit, and we had no further issues.

During practice, we were one of the fastest, if not the fastest, C2 cars in the field – and we were also very fuel-efficient, which gave us all a lot of hope for a good result come race weekend.

Sadly, the race brought us a mechanical failure, and we retired. However, during that first season, we learned so much, and in 1986, we won the Group C2 Team World Championship, a fine result for a great little team.

I drove four seasons with Ecurie Ecosse and finished my Group C career driving a works Nissan R88C in Group C1 at Le Mans in 1988 with my friend Win Percy and veteran Australian driver Alan Grice, placing 15th overall.

Five fantastic seasons in what I consider to be one of the best formulae the FIA has ever devised – super-fast, super-competitive, and certainly the best category I have ever raced in!

Mike WildsAugust 2024

PREFACE

From the start of the Group C era, Jürgen Barth was President of the Endurance Commission of the BPICA (Bureau Permanent International des Constructeurs d’Automobiles) and created OSCAR (The Organisation for Sportscar Racing) with Chris Parsons and was responsible for organising all races from the outset until 1988. He also drove in a fair number. Here is his mission statement and summary of the decade.

Group C was introduced by the FIA to replace Group 5 (open to special production cars) and Group 6 (two-seater racing cars). Although the new category was introduced in 1982, we must dive back into the mid-1970s for its roots. During those days the French ACO introduced the GTP-category for the Le Mans 24-Hours. Limited to a weight of 800kg and a maximum fuel capacity of 100 litres, GTP cars were roofed prototypes using 3.0-litre engines such as those employed in Formula 1. It was a great loss that legendary cars such as the Porsche 917 and the Ferrari 512 became obsolete, as the big 5.0-litre engines were no longer allowed. When Ferrari decided to concentrate on Formula 1, Matra dominated Le Mans. Then, when Matra decided to follow Ferrari into Formula 1, it was Mirage from the UK with Derek Bell and Jacky Ickx who claimed victory at Circuit de la Sarthe with their GR8. A few years later, in 1980, Jean Rondeau won the Le Mans 24-Hours in his own Rondeau M379B, together with his fellow countryman Jean-Pierre Jaussaud.

In 1982, the BPICA and FIA created Group C for cars weighing a minimum of 800kg with a maximum fuel capacity of 100 litres. The racing distance was limited to 1,000 kilometres with a restriction of five refuelling stops during a single race. With these rules, the FIA hoped that manufacturers would shift their concentration away from the worrying climb in engine output. Ford and Porsche were the first manufacturers to enter the championship with the Ford C100 and Porsche 956.

They were followed by Aston Martin, Jaguar, Lancia, Mazda, Mercedes, Nissan and Toyota. Ever-rising costs remained a significant issue, so an additional category was developed in 1983 for privateers and smaller teams, initially known as Group C Junior. Instead of five refuelling stops within a 1,000-kilometre race distance, Group C Junior cars were allowed 330 litres per 1,000 kilometres. The minimum weight for these cars was 700kg. Different engine types were used, such as the 3.5-litre BMW M1 or the 3.3-litre Cosworth DFL. Lightweight turbo engines were used, as well as engines from Austin-Rover. In 1984, the FIA renamed Group C Junior as Group C2. The engine must be out of an FIA Homologated Car so as not to allow special racing engines to be used.

Jürgen Lässig drove the Obermaier 956 to 4th place in the DRM round at Berlin’s AVUS circuit on 1 February 1983.

Group C quickly grew in popularity, and Bernie Ecclestone also remarked that we had over eight manufacturers competing in Group C, and no one was building special F1 engines any more. So, at a meeting at London Airport, Max Mosley (FIA President) and Bernie came up with the new engine rules, ending the homologated engine with the fuel consumption limitations, and opening it up for racing engines of up to 3.5 litres. Under protest from most manufacturers, the new technical rules were adopted, and when Peugeot recorded the highest top speed during qualifying for the 1988 Le Mans 24-Hours, reaching 407km/h, the FIA adopted a new rule book that became effective in 1991. Category C1 was introduced to mandate normally aspirated 3.5 litre engines, similar to what were used in contemporary Formula 1, and generating less power than was found in Group C cars then. As these engines were not affordable to privateer and smaller teams, Group C started to die. At the start of the 1991 season, only a handful of C1 cars formed the grid. As a result, the FIA allowed cars complying with the pre-1991 Group C rules to participate. However, interest was lacking by now, and after a poorly supported World Sportscar race at Magny-Cours in 1992, the championship came to a premature end.

The diversity of cars that competed under Group C regulations, combined with their sheer speed, attracted vast crowds around the world. It was a shame to see the second most popular category in motorsports, just behind Formula 1, disappear so suddenly.

Nowadays, the Group C Racing Series hosted under the Peter Auto flag recreates the great days of endurance racing with cars that actually raced in the World Sportscar Championship. Across Europe, with races in Spain, Belgium, France and Italy, fans can still enjoy the sounds and shapes of these great cars. The highlight of the Peter Auto calendar is the biennial Le Mans Classic, which features a race for Group C cars from that particular era.

Jürgen Barth August 2024

TIMELINE

1981

Group C is mooted as a replacement for Group 5 special production cars (e.g. Porsche 935) and Group 6 open-top sports prototypes (e.g. Lancia LC1, Porsche 936).

1982

Group C represents the FIA World Endurance Championship. Ford, Lancia and Porsche lead the way; Rothmans Porsche wins the Manufacturers’ title with four out of eight race victories; Jacky Ickx is Champion Driver.

1983

Group C2 ‘Junior’ class introduced, won by Gianni Alba. Group C also represents the European Endurance Championship for one season. Jacky Ickx wins the Drivers’ title again, while Rothmans Porsche is also Manufacturers’ Champion, winning six out of seven rounds.

1984

Rothmans Porsche takes the Manufacturers’ title with seven out of eleven wins; Stefan Bellof is Champion Driver.

Mario and Michael Andretti debuted their 962 #001 on pole position for the 1984 Daytona 24 Hours but retired after 127 laps with engine cooling issues.

1985

Rothmans Porsche is Group C World Champion team, and Hans-Joachim Stuck and Derek Bell are joint Drivers’ Champions. Teams’ titles are introduced for Group C2 and GT cars, replacing the traditional Manufacturers’ awards. Group C2 Drivers’ and Teams’ titles are won by Gordon Spice and Ray Bellm of Spice Engineering.

1986

Group C represents the FIA World Sports Prototype Championship. Brun Motorsport (Porsche 956/962C) wins Teams’ title; Derek Bell is Drivers’ Champion.

1987

Silk Cut Jaguar wins the Teams’ prize, with eight out of ten race victories. Raul Boesel is Champion C1 Driver. Fermin Vélez wins C2 Drivers’ title, Spice is C2 Teams’ winner.

1988

Silk Cut Jaguar win the Teams’ World Sports Prototype Championship with six out of eleven race wins (to Sauber-Mercedes’ five wins); Martin Brundle won the Drivers’ title. Gordon Spice and Ray Bellm were joint winners of Group C2 Drivers, and Spice Engineering won Group C2 Teams.

1989

Sauber-Mercedes wins World Sports Prototype Championship for Teams, winning seven out of eight rounds, Jean-Louis Schlesser is Drivers’ Champion; Chamberlain Engineering wins C2 Teams’ prize, Fermin Vélez is top C2 driver. Last year of C2.

1990

Sauber-Mercedes wins the C1 Teams’ prize and overall Championship with a magnificent eight out of nine race victories; Jean-Louis Schlesser takes the Drivers’ title.

1991

Group C now represents the FIA World Sportscar Championship, with Group C divided into Categories 1 and 2, dependent on compliance with new regulations. Silk Cut Jaguar wins the Teams’ title from Peugeot Talbot Sport; Teo Fabi is the Drivers’ Champion.

1992

Peugeot Talbot Sport wins the Teams’ title with five out of six race victories in a shortened Championship schedule. Derek Warwick and Yannik Dalmas are joint Drivers’ Champions. The Championship fizzles out in the final round at Magny-Cours, and in October 1992, after four decades, the FIA officially cancelled what became known as the Sportscar World Championship.

1993

Le Mans composes a special prototype category for Group C cars. Peugeot Talbot Sport takes the first three places, with Toyota taking 4 to 6.

1994

Last appearance of Group C cars at Le Mans: Dauer-Porsche 962 take 1st and 3rd places, with Toyota 2nd.

2002

Start of the Group C Revival. The category flourishes over the two following decades, from 2016 under the dedicated classic racing Peter Auto administration, with rounds held at Spa Classic, Paul Ricard, Le Mans Classic, Dijon, Estoril and Mugello, plus Silverstone Classic, Goodwood Members and Donington Historic.

2025

Group C relaunched as a standalone series in the Masters’ Historic Championship.

Group C represented other international sports-prototype race series, including the All-Japan Sports Prototype Championship (1983–92), the DRM and ADAC Supercup in Germany, the UK’s Thundersports, and Europe’s Interserie Championships. Broadly similar rules were used in the North American IMSA Grand Touring Prototype (GTP) series (1981–93), with plenty of top-line crossover IMSA entries participating in certain Group C events, especially the Le Mans 24-Hours.

INTRODUCTION

In its 1980s heyday, Group C was the zenith of long-distance sports-prototype competition and, viewed retrospectively, one of the most exciting and intense periods of motor racing in history. The Group C category was synonymous with the FIA’s World Endurance Championship from 1982 to 1985, the retitled World Sports Prototype Championship from 1986 to 1990, and the World Sportscar Championship from 1991 to 1992.

The Mercedes-Benz C11 of reigning champions Jean-Louis Schlesser and Jochen Mass heads the C291 of Karl Wendlinger, Michael Schumacher and Fritz Kreutzpointner at Le Mans 1991, the lead car retiring at 22 hours when a broken alternator bracket compromised the water pump, destroying the engine.

Whilst plenty of Group C entrants also ran in IMSA’s GTP category in North America, I do not cover them here as, realistically, that constitutes a book in its own right. Nor do I venture into the All-Japan Sports Prototype Championship, where, again, the rules and duration were broadly similar, for the same reason.

The first manufacturers to join the series were Lancia, Ford and Porsche, quickly followed by other automotive titans, including Jaguar, Mercedes-Benz, Nissan, Toyota, Mazda and Aston Martin. Many of these teams also took part in the North American IMSA Championship, since its GTP class had similar regulations. A year after Group C was introduced, a junior category called Group C2 was introduced, attracting a swathe of smaller privateer teams such as Spice Engineering, Ecurie Ecosse, Argo, Alba, Lola and Tiga, employing engines such as Ford-Cosworth, Chevrolet V8 and BMW sixes. Thereafter, grids comprised both Group C1 and C2 cars, till C2 was dropped at the end of the 1989 season as new rules were announced.

Support for Group C from the main motor manufacturers grew steadily, with each make adding to the diversity of the series, and whilst turbocharged engines were commonplace, it was theoretically possible for large-capacity, naturally-aspirated engines to compete with smaller forcedinduction engines, which amounted to C1 versus C2, though in practice C2 cars never quite matched the C1s for outright wins. Race distances were over at least 1,000 kilometres and usually lasted more than six hours, emphasising the endurance aspect of the events. Again, the rules changed for 1990 to more than halve race distances. The ongoing fuel consumption regulations placed the onus on race teams to conserve fuel over the course of a race, and only throw caution to the wind when the result depended on deploying the throttle pedal.

The 3.9-litre Ford-Cosworth DFL V8 Lola T610 of Guy Edwards, Rupert Keegan and Nick Faure is fettled in the Le Mans pitlane ahead of the 1982 race, as the Andretti’s Mirage M12 passes by.

FASTER THAN F1

In 1988, a French WM-Peugeot recorded the highest-ever speed achieved along Le Mans’ Mulsanne Straight, doing 405km/h (252mph), way faster than Formula 1 cars – though the gearing for such a long 6km (3.7 miles) straight is a key factor in attaining such a speed. However, the authorities then decided not merely to construct enormous chicanes at two locations along the straight to reduce speeds (acting like half-roundabouts) but also to restrict the performance of cars built to the original rules, such as the Porsche 962C that was used by many privateers.

This directive eventually benefited the larger and wealthier manufacturer teams, such as latecomers Peugeot, who were using F1-derived 3.5-litre engines. Whether intentional or not, the move brought about the rapid downfall of Group C because the smaller private teams, such as Spice and ADA, lacked the budgets for brand-new F1 engines. The 1993 Group C Championship was cancelled before the first race due to a lack of entries. The ACO, organisers of the standout race, the Le Mans 24-Hours, still permitted Group C cars to run, though the 1994 race was the last one in which any Group C cars participated. A new category introduced by race organisers drew in modified Group C cars. One such, the Dauer-Porsche 962 – a former C1 car disguised as a road-legal GT car – won the 1994 race, and the open-top TWR-Porsche WSC-95 won Le Mans in 1996 and 1997. By this time, the real Group C cars had been pensioned off – not for good, though – as they would have another more secure bite of the cherry, running as historic racing cars from 2007 going forward.

REVIVAL

Today, there is a dedicated Group C Championship featuring many of the original protagonists, running in conjunction with the French Peter Auto race promoter under the auspices of Group C Racing –– with rounds at Classic Le Mans, Spa and Silverstone Classics, amongst others. From 2025, a new championship for Group C cars was scheduled to launch in the Masters’ Historic Racing series, organised by Masters boss Frederick Fatien. The aptly named Historic Group C Collection is located at specialist and driver Henry Pearman’s barns in rural Kent, containing at least 30 cars – Porsches, Jaguars and Toyota.

GROUP C TEAMS

The C1 series’ main contenders were the factory-enabled teams of Jaguar, Sauber-Mercedes (Mercedes-Benz), Lancia, Porsche, Peugeot, Mazda, Nissan and Toyota, with top-line privateer teams such as Kremer Racing, Brun Motorsport and Joest (Jöst) Racing, and a surprisingly large number of independent constructors including Spice, Tiga, Ecosse, Gebhardt and Alba, to name but a few, running in the C2 Junior category. There was never any sign of a Ferrari works team – although the Lancias used Ferrari engines – and Ford was an early drop-out.

The 7.0-litre V12 TWR Jaguar XJR-8 that won the Spa-Francorchamps 1,000km in 1987 is fettled in the modern Spa pitlane during the 2022 Spa Classic meeting.

Jaguar’s XJR series of racing prototypes were campaigned from 1983–91 in both Group C and IMSA GTP, with the early cars developed by Group 44 in the USA, followed by a switch to Tom Walkinshaw Racing (TWR). Jaguar scored three World Championship titles – in 1987, 1988 and 1991 – including two overall Le Mans wins in 1988 and 1990. The powertrain evolved from the V12 through Turbo V6 and, latterly, the Cosworth-built 3.5-litre V10 XJR 14, which also provided the basis post-Group C for the double Le Mans winning TWR-Porsche of 1996 and 1997.

Designed by Lee Dykstra with aerodynamicists Max Schenkel and Randy Wittine, the 600bhp Jaguar XJR-5 V12 was built by Bob Tullius’ Group 44 Team in August 1982, pictured here in Henry Pearman’s Historic Group C collection. At Le Mans 1985, one of the two Group 44 XJR-5s, driven by Tullius, Chip Robinson and Claude Ballot-Léna, placed 13th, the first time a Jaguar had finished Le Mans since 1963.

The third round of the 1989 WSPC at Jarama was the 480km Repsol Trophy, won by the Sauber-Mercedes C9 of Jean-Louis Schlesser and Jochen Mass, seen here passing the TWR-Jaguar XJR-9 of John Nielson and Andy Wallace, which came 6th.

Lancia’s LC2 was the successor to its open-topped Group 6 LC1 and was campaigned from 1983 to 1986, with privately operated LC2s continuing as late as 1991, though with no outstanding success. The works Lancias won a World Championship race in 1983, 1984 and 1985, often dominating qualifying but fading with reliability issues against the more reliable Porsches and Jaguars. From the outset, Mazda entered the C2 category, then embraced C1. Johnny Herbert, Bertrand Gachot and Volker Weidler drove a 787B in IMSA GTP trim to a surprise victory at Le Mans in 1991. Mazda’s rotary ‘Wankel’ engine was also notoriously deafening.

The 1990 Spice SE90C driven by Desiré Wilson/Lyn St James/Cathy Muller in the1991 Le Mans 24hrs (DNF), getting a run up Goodwood Hill. ‘The Pink Spice’, chassis SE90-C-017 was one of the last C1 Spices built.

Peter Sauber’s Sauber squad embraced the series from the outset, truly coming into its own as a Mercedes-Benz satellite in 1985. In 1990, Sauber-Mercedes morphed into a full-on Mercedes-Benz team, with the 5.0-litre twin-turbo V8-powered C11 replacing the Sauber C9. With several top-line drivers, including Jochen Mass, Jean-Louis Schlesser and Michael Schumacher on the driver roster, the C11s won all but one of the races entered, easily winning the 1990 World Sports Prototype Championship. Reliability issues with the replacement car meant the C11 continued to be used until mid-season when the C291 was introduced. In 1993, Sauber embraced F1 and, one way or another, has never left.

Perhaps surprisingly for a major player, Nissan’s Group C entries were based on the customer March chassis with Lola underpinnings, which were theoretically available to any private team. Although Nissan’s R90C drivers took Japanese domestic Championship honours every year from 1990 to 1992, on the international stage there were just seven podium finishes across the 1989 and 1990 seasons, but no wins, with 5th overall at Le Mans in 1990.

Aston Martin supplied engines to the Nimrod and EMKA (see Pink Floyd) teams in the early years of Group C.

In 1989, the works’ spin-off Proteus Technology team built five Group C chassis, designated AMR/1–5, running Callaway-tuned 5.3-litre V8 engines, but despite high-calibre drivers like Brian Redman, they were also-rans in a competitive field. The team closed in 1990.

Toyota’s early Group C cars were built by Dome and then by TOM’S, which moved in-house in 1987. There was little success until 1992 when the first race for the 3.5-litre V10-powered TS010 yielded a win at Monza and an All-Japan title in 1993.

Peugeot’s 905, powered by the 3.5-litre V10, debuted in late 1990, notching up nine race wins, including overall victory at Le Mans in 1992 and the diminished Sportscar World Championship in 1992, plus the post-SWC event in 1993.

Standing on its airjacks in the Silverstone pitlane, the Brun Motorsport 956 #106 came 9th in the 1986 1,000km, driven by Walter Brun and Frank Jelinski.

Stalwarts of the WSPC and WSC, Porsche embraced Group C from the get-go with its 956, which, together with its successor, the 962 (essentially the same car but with its chassis tub extended so the driver’s feet were behind the front axle rather than ahead of it) is the most successful racing car of all time. It won the World Sports Prototype and Sports Car Championship five times in succession, also an unparalleled achievement in the sport. Stateside, it won the IMSA Championship three times, despite not being allowed to enter for the first two years of its life, and in 1991, in its tenth season of racing, it was still good enough to win the Daytona 24-Hours outright – and for the fifth time.

Between 1982 and 1991, 27 examples of the 956 (including four 956B evolutions) and 120 units of the 962 (including ten works cars) were built. After Porsche withdrew at the end of 1988, customer teams such as Kremer Racing, Richard Lloyd’s GTi Engineering, Brun Motorsport and Joest Racing continued to operate the cars and develop them to some extent, such as substituting aluminium tubs with honeycomb cells.

DRIVERS

Across the board, Group C was peppered with well-known drivers, many from F1 and others being recent Le Mans winners.

Derek Bell and Jacky Ickx enjoy a moment with Ferry Porsche.

Works Porsche drivers take a break at Spa-Francorchamps during the 1,000km, 1984: from left, Stefan Bellof, Derek Bell, Jochen Mass, Jacky Ickx, Vern Schuppan and John Watson. Winners were Bell/Bellof, with Ickx/Mass 2nd, and Watson/Schuppan 6th.

In the Porsche camp alone, we find Derek Bell, Jacky Ickx, Jochen Mass, Mario Andretti, John Watson, John Fitzpatrick, Hans-Joachim Stuck, Klaus Ludwig, Stefan Bellof, Mike Wilds and Vern Schuppan.

Private teams abounded, including Brun, Fitzpatrick and Jöst in C1, and Spice, Tiga and Ecurie Ecosse in C2. At Sauber Mercedes-Benz, future F1 stars Michael Schumacher, Karl Wendlinger and Heinz-Harald Frentzen were groomed under the tutelage of 1990s’ champion drivers Jean-Louis Schlesser and Mauro Baldi. Inevitably, some drivers flitted between teams, slipping backwards and forwards from one to another in a high-octane game of musical chairs, with some, such as Jochen Mass, Jean-Louis Schlesser, Mauro Baldi, John Watson and Johnny Dumfries sampling multiple marques in the course of the era. At TWR Jaguar, Andy Wallace, Jan Lammers, Johnny Dumfries, Stefan Johansson, Michele Alboreto, Tom Kristensen, Johnny Herbert and Martin Brundle played the starring roles; Mazda hired Yojiro Terada, Johnny Herbert, Bertrand Gachot and Volker Weidler, while Mark Blundell, Julian Bailey, Kenny Acheson, Geoff Lees and a host of others drove the Nissans, and Derek Warwick, Phillipe Alliot and Geoff Brabham were colleagues at Peugeot. As the chapters unfold, we will get the names of numerous drivers who starred in Group C2 as well, including Ray Mallock, David Leslie, Gordon Spice, Ray Bellm, Tim Lee-Davey, and our Foreword writer Mike Wilds – to name but a few.

STREET CARS NAMED DESIRE

Two Porsche-driving race- and title-winners, Derek Bell and Vern Schuppan, had road-going versions of the 962 made in their own names, though proving somewhat disastrous for Vern in commercial terms. I had a go in the one-and-only Derek Bell car when Antony Fraser and I journeyed to the Forest of Dean to review it, courtesy of Porsche racer and collector Paul Howells, who owned it at the time. The Derek Bell Signature Edition 962 was built by the former head of Sauber’s F1 team at the cost of around £1.3m, based on a Fabcar monocoque and an integral multi-tubular roll-cage. It was equipped with a twin-turbo 3.6-litre 993 GT2 engine, producing 580bhp and 546lb/ft of torque, with an all-up weight of just 830kg. The suspension was by coilover Koni adjustable dampers, with adjustable ride height, and stopped by 350mm floating Brembo discs with adjustable bias. It poured with rain on our visit, but Paul magnanimously let us loose on the local country roads despite the weather. Notwithstanding its road-going set-up, I can only reflect on how amazing this car would be on a racetrack.

As for the Schuppan version, Vern sought to emulate teams such as Kremer Racing, Team Jöst and designer John Thompson, who were developing bespoke components and even entire chassis for the 962C. With design input from ex-Lotus F1 stylist Ralph Bellamy, the road-legal 962 was based on a Team Schuppan Le Mans 962, which enabled it to pass the type-approval process. The Schuppan 962 LM was created on the Advanced Composite Technology (ACT) carbon-fibre chassis and powered by the 962’s 2.65-litre turbocharged quad-cam 24-valve flat-six engine. Just three cars were built in the Tiga Cars factory. With a planned production run of 50 units, the project foundered in 1991 when Schuppan’s Japanese client and sponsors bailed on him.

Having competed in F3000 and F1, firm friends Mark Blundell and Julian Bailey were teammates at Nissan Motorsports in 1989 and 1990, and, subsequently, the BTCC. Blundell also shared the winning Peugeot 905 at Le Mans in 1992, while Bailey returned briefly to F1 and then Touring Cars.

There was – and still is – another way for humbler mortals to emulate the Group C gods on the open road, and it is called the Ultima. From 1982, Group C imagery and performance were available to regular sportscar drivers in the shape of the road-going Ultima. Hinckley-based automotive engineer and designer Lee Noble launched Noble Motorsport with the Ultima Mk1. With looks that would not disgrace a C2 car, the Ultima was built on a squaretube spaceframe chassis, and its V6 engine and transmission were taken from a Renault R30 with other components from the Ford, Lancia and Austin-Rover parts bins. Cars were assembled at the factory or sold as kits for self-build. Campaigned in domestic club events, by 1991 it was proving too successful on track and was banned from racing. It was re-engineered by Ultima’s first customer, Ted Marlow, to run with a small block Formula 5000 Chevrolet V8, increasing potency somewhat. The Marlow family, under Richard Marlow, acquired the Ultima marque in 1992, and it has gone from strength to strength, with the Ultima GTR appearing in 1997, the updated Evolution model arriving in 2015 and the RS available in 2021.

Weighing just over 1,800lb, the Fabcar chassis Derek Bell Signature Edition 962C was surely one of the most beautiful racing cars to hit the road.

The Derek Bell Signature Edition 962C used push-rod suspension and was powered by a 580bhp 3.6-litre twin-turbo 993 GT2 flat-six, producing 546lb ft of torque.

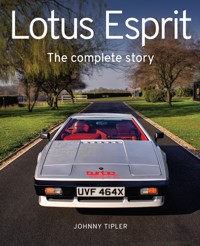

While the Ultima was originally conceived as a ringer for a Group C car, other road-going brands might legitimately propose their own products as deserving of the C2 mantle. For example, Lotus’s Esprit S300 – which ran at Le Mans in 1993 and ’94 – and BMW’s M1 Procar, examples of which were seen in the early WEC rounds, were worthy candidates.

Austerely minimalist like its racing counterparts, exemplified by the flat-bottomed steering-wheel rim, built-in roll-cage, carbon-fibre seats, bare dashboard and race-car-style instrumentation, and of course the recumbent driving position as demonstrated by the author, the cockpit of the Derek Bell 962C had no creature comforts, not even in the upholstery.

One way for the Group C fan to experience the thrills of racing was in an Ultima Evo.

THE GENESIS OF GROUP C REGULATIONS

One of the key instigators of the rules and regulations for Group C was Jürgen Barth, son of the illustrious Porsche pilot of the 1950s and early ’60s, and winner of the Le Mans 24-Hours in 1977 in a Porsche 936. It is not widely known that the dimensions of a Group C race car correspond with those of the 917, and it is thanks to Jürgen’s background as a Porsche factory technician, works driver and emissary that he was able to convince the FIA to accept them. Nevertheless, it was Group C’s stringent fuel restrictions that gave the constructors pause for thought prior to the series getting under way.

Here is Jürgen’s assessment of how the scene was set for the implementation of the new category:

The World Sportscar Championship regulations in play between 1976 and 1980 were aimed at attracting the top manufacturer teams, but the Group 5 silhouette racing cars – like the Porsche 935 – that emerged were innovative in the quest for brute power but lacked the elegance and pioneering quest for technical evolution that sports-prototypes represented. Furthermore, the FIA allowed Group 6 prototypes – like the Porsche 936 – to race in parallel with the silhouette cars, and it wasn’t only Porsche who felt it was time for a change under the circumstances.

Jürgen Barth remembers well the initial discussions back in 1979 at the International Permanent Office for Vehicle Construction (BPICA) in Paris:

As no manufacturer’s board existed at the FIA at that time, all topics related to the car manufacturers were sorted out first at the BPICA, and afterwards presented to the respective FIA boards. At the time, I was chairman of the BPICA’s sportscar board, and our basic aim was to attract more manufacturers into long-distance endurance world championships as well as national championships. First of all, we needed to implement free regulations for racing cars without specific reference to existing production vehicles. During the course of this procedure, I vividly remember dropping by the Porsche Museum at Zuffenhausen on my way to a board meeting in Paris, in order to calculate the interior width and the windscreen proportions of a Type 917, and thus glean a set of measurements that would serve as the basic interior dimensions for the new Group C chassis. What I had in mind then was a vehicle corresponding to the Ferrari 512 prototype, or, in this case, the Porsche 917.

The privately entered 2.7-litre twin-turbo Porsche 936C of Ernst Schuster, Siegfried Brunn and Rudi Seher came 6th overall in the 1986 Le Mans 24-Hours.

It was an ambitious proposition, but all the manufacturers interested in establishing and participating in the new Group C formula did indeed accept those actual dimensions. Participating manufacturers included Ford, Mercedes-Benz, Lancia, Jaguar, Peugeot, Porsche, Nissan, Mazda, Toyota, and Aston Martin.

Jürgen explained:

From the start the board agreed that fresh ground needed to be broken in terms of propulsion and power delivery. Two options were considered: restrict the intake airflow rate or standardise the fuel consumption. Eventually, the decision was taken in favour of restricting fuel consumption. This effectively meant that the engine had either to originate from a homologated Group A or Group B series-production vehicle or from a manufacturer of vehicles already homologated by the FIA. Needless to say, the whole engine did not necessarily have to be used as an off-the-shelf unit, though its most fundamental parts, the engine block and the cylinders and cylinderheads, certainly did. All other parts could be subject to any modification whatsoever.

Thanks to Jürgen Barth, the inner dimensions of a Group C race car, like the 956, correspond with those of the Porsche 917, such as Claudio Roddaro’s 1969 ex-works car, driven here by the author at Donington Park circuit fifty years later.

There was some fine detail as well.

The total amount of fuel that could be carried on board was limited to a maximum of 100 litres. Nevertheless, given that the fuel lingering within the pipes still had to be taken into account, the actual amount that could be stored in the fuel tank ended up being approximately 98 litres.

That rule provided a basis for regulating the number of pit stops permitted for refuelling during the race, as follows:

Races of less than 165 km: No refuelling permitted.

Races of 165 to 330 km: 1 pit stop permitted.

Races of 330 to 500 km: 2 pit stops permitted.

Races of 500 to 665 km: 3 pit stops permitted.

Races of 665 to 830 km: 4 pit stops permitted.

Races of 830 to 1,000 km: 5 pit stops permitted.

12-Hour Races: 12 pit stops permitted.

24-Hour Races: 25 pit stops permitted.

This resulted in an average fuel consumption of 60 litres per 100km, which still seems quite generous today. However, when Group C racing regulations came into effect in 1982, a further reduction to approximately 50 litres per 100km was stipulated for the 1984 season. As Jürgen admits:

That still seems a lot of fuel today, but remember that we are talking about engines with an output of 600bhp, which did not benefit from today’s state-of-the-art electronics, so this really was a milestone – not least because of the incentives and hurdles that faced the technicians and race engineers involved, who applied their skills to make the engines and fuel systems attain and operate at that limit.

Moreover, evolving developments like injection electronics, along with newly introduced materials for the coating of cylinders and so on, contributed further to the reduction of fuel consumption. This was technology that also benefited the general public, as such revelations from the race track soon filtered down into series production vehicles.

So, in 1984, the practical consequences were as follows:

Races of 800 km (or 500 miles): Up to a maximum of 425 litres permitted.

Races of 1,000 km: Up to a maximum of 510 litres permitted.

9-Hour Races: Up to a maximum of 830 litres permitted.

12-Hour Races: Up to a maximum of 1,105 litres permitted.

24-Hour Races: Up to a maximum of 2,210 litres permitted.

As with many innovative regulations, scepticism was rife, as Jürgen concedes:

Nocturnal pit stop for the winning 962C #003 of Hans Stuck, Derek Bell and Al Holbert, Le Mans 1986.

The atmosphere and tension at the first races of the season was wound up to a fever pitch, and malicious gossip amongst the pessimists and pundits suggested that none of the racing cars would cross the finish line as they would inevitably run out of fuel out on the circuit during the race. But it didn’t turn out like that at all. During the Group C era, Porsche won the World Sportscar Championship in 1982, 1983 and 1984, with Jacky Ickx crowned World Endurance Drivers’ Champion in ’82 and ’83; Stefan Bellof was the Drivers’ title winner in ’84. The Norbert Singer-designed Type 956 was superseded in ’84 by the Type 962 evolution, which won the World Sportscar Championship in 1985 and 1986 and helped Derek Bell to win the Drivers’ title. Many of the 91 cars built raced successfully as works and private team entries in the concurrent IMSA, Interserie and Japanese endurance series, and the 962 was still a race winner in 1992.

CHAPTER 1

DESIGN AND SPECIFICATION

The Group C racing category’s history harks back to the mid-1970s, when motor sport’s ruling body – the Federation International Automobile (FIA) – adopted the Le Mans 24-Hour race organisers’ then-current GTP (Grand Touring Prototype) category. This was a class for closedroof prototypes with certain dimensional restrictions, but instead of imposing limits on engine capacity (which had caused the demise of the highly successful Porsche 917 and Ferrari 512 after 1971), it placed limits on fuel consumption. There was a minimum weight limit of 800kg and a maximum fuel capacity of 100 litres; with cars restricted to five refuelling stops within a 1,000-kilometre distance – a typical distance for an endurance race, for example the Monza 1,000km – the cars were effectively allowed to consume 600 litres of fuel per 1,000 kilometres. The FIA’s objective was to dissuade manufacturers from focusing on producing ever more powerful engines, which could be achieved by simply increasing turbocharger boost pressure. At the time, the 3.2-litre twin-turbo Porsche 935 (1977–81) developed more than 800bhp.

ANTECEDENTS

Group C cars’ bodywork had come a long way since the days of Porsche’s all-conquering 917 (1969–71); in the late 1970s, Formula 1 car design espoused ground-effect bodywork (see the groundbreaking Lotus 78 and 79 F1 cars), an aerodynamic phenomenon responsible for huge decreases in lap times, mostly due to the vastly quicker cornering speeds that were enabled by the downforce generated by the skirts, spoilers and diffusers surrounding the extremities of the car’s bodywork. By trapping the air beneath the car, it was effectively and literally sucked down onto the track surface. Following in the wake of F1, Group C racing cars had ground-effect aerodynamics designed into their configurations from the word go. They were, therefore, much faster than the preceding generation of sports-prototype racing cars.

Equally fundamental to the construction of Group C racing cars was their chassis material and configuration. Again, whilst Formula 1 (and the majority of single-seater racing cars) had employed monocoque aluminium tub chassis since the early 1960s, Porsche, for example, built its sports racing prototypes on complex aluminium multi-tubular spaceframe chassis, up to and including the open-top 936 that won Le Mans in 1977 and 1981. So, like their F1 counterparts, Group C cars utilised angular aluminium central monocoque hulls or tubs that supported subframes which provided locations for the sophisticated suspension pick-up points and engine mounts – plus the cockpit (more a survival cell with integral steel rollbars) – all clad in suitably streamlined aerodynamic bodywork. And, just as the F1 chassis morphed at the same time from aluminium into lighter, stronger carbon-fibre honeycomb and Kevlar, the same happened to Group C cars. Metal tubular subframes supported the various ancillaries front and rear, such as oil coolers, fluid reservoirs and wing mounts.

The 5.3-litre Nimrod Aston Martin NRAC2 of Viscount Downe, driven by Ray Mallock, Mike Salmon and Simon Phillips, came 7th overall at Le Mans in 1982.

MANUFACTURERS’ ATTRACTION

From the outset, Group C was essentially a series based on fuel consumption. Anything was possible in terms of engines, provided they could do a whole race on a limited amount of fuel, and this allowed production engines like Aston Martin and Mercedes-Benz V8s and Jaguar V12s to compete head to head with Mazda’s Wankel rotary engines and Ford’s Cosworth V8s. Some criticised the formula, saying that cars had to hold back early on or back off late in the race in order to go the distance, but it produced a great variety of solutions, attracted many manufacturers and provided some great racing. The sights and sounds of Jaguars racing against Sauber-Mercedes and Porsche, along with the Japanese manufacturers Mazda, Nissan and Toyota, as well as Aston Martin, Spice, Tiga, Ecurie Ecosse and Gebhardt competing in the Group C2 category, were truly epic.

LE MANS SPRINGBOARD

Just as many sportscar racing series do, Group C started off at Le Mans. In 1978, Renault had won with a Group 6 open two-seater sportscar, but in the cause of better aerodynamics, they had fitted a bubble top with a small slit in front for driver visibility and a hole in the roof so that the car remained open to the elements and complied with the rules as they then were. This was the catalyst for the sports-GT-prototype class that started at Le Mans, bearing similarities to the sports-racing cars of the late 1960s and early 1970s, like the Ferrari 512S and Porsche 917, which were closed-cockpit Group 6 cars.

The new Group C regulations for 1982 endurance racing called for recognised engines homologated for Group A or Group B production cars, but of unlimited capacity. By restricting fuel tank size and specifying a minimum of 102.5 miles (165 kilometres) between refuelling pit stops, fuel consumption needed to be at least 4.6 miles per gallon. Wheels were not permitted to have a rim width exceeding 16in, minimum weight with a two-seater body of specified windscreen area must not be less than 800 kilogrammes without fuel, and to some extent, ground-effect downforces were reduced by under-shield requirements.

The WM-Peugeot P83 PRV was driven at Le Mans in 1983 by Jean-Daniel Raulet/Michel Pignard/Didier Theys, with Roger Dorchy in reserve.

Le Mans regular Jean Rondeau was one of the first constructors to embrace the rules, building his cars specially for Le Mans and achieving a remarkable victory in 1980 as an owner-driver. The WM-Peugeots were early exponents of the class, recording the fastest-ever speed on the 3.7-mile-long Mulsanne Straight, pre-1990 chicanes, at 252mph. The fastest speed recorded with the chicanes in place is 227mph, set by Mark Blundell in a Nissan R90CK.

Alain de Cadenet, whom the author interviewed in 2007 in Snowmass, Colorado, created two eponymous cars in 1975, #HU1 placing 3rd at Le Mans in 1976 and 3rd again in 1980. Based on Lola T380-Cosworth V8s with Thompson-built chassis, one morphed into an Ecosse C2, another into an ADA-Ford C2. De Cadenet also managed the Rondeau Team, and he drove the GRID Plaza C2 in 1982, Charles Ivey’s 956 in 1984, and then for Courage Compétition, placing 15th in 1985’s Le Mans and 11th in 1986.

The very early days of Group C at an international level saw some weird and wonderful oddities. The Lola T600 was the first shot at a production Group C car, but had to run with a hole in its roof before the FIA ratified the Group C rules. The Kremer brothers Erwin and Manfred turned the clock back and built a Porsche 917 out of spare parts and raced it at Le Mans in 1981, without achieving anything approaching a revival. Then, in 1982, the Porsche 956 arrived on the scene. The 956 and subsequent 962 offspring became the core Group C cars for at least three-quarters of the series’ duration, and, whilst the factory fielded a Rothmans-sponsored works team for the first half of the series, several private teams enjoyed great success with the 956 and 962, notably Reinhold Jöst’s Joest Racing Team, Walter Brün’s Brün Motorsport Team and Richard Lloyd Racing.

Over the years, Lancia won fifteen World Rally Championships, as well as the World Championship for Makes between 1979 and 1981 with a Group 5 Beta Montecarlo 1.4 turbo, but this was not eligible for the WEC so they created LC2 and recruited F1 drivers Riccardo Patrese and Andrea De Cesaris who could put an LC2 on pole, although they lacked reliability, and the Porsches were always there to pick up the pieces. Porsche’s early stranglehold on Group C was defused by Jaguar’s US entrant Bob Tullius running Group 44 Jaguars at Le Mans in 1984, scoring respectable finishes in 1984 and 1985.

ETCC winner Tom Walkinshaw was retained by Jaguar and created a run of carbon-fibre monocoque TWR Jaguar XJR-6s that ran well at Le Mans, Brands Hatch and Spa-Francorchamps in 1985. In 1986, the XJR-6s raced in Silk Cut livery, winning the 1,000km at Silverstone. Also in 1986, the Kouros-backed Sauber-Mercedes V8 arrived and was straight away on the pace of the Porsches and Jaguars, though in 1987, Jaguars won eight out of ten races in the series. At Le Mans, the battle between the formerly dominant Porsches and the Jaguars raged on until dawn, but the Jaguars finally fell by the wayside, and Porsche took the victory once more.

The Sauber-Mercedes only ran in European rounds for the moment and the works Porsches withdrew mid-season as the firm’s IndyCar project started to consume corporate resources. In 1988, Mercedes-Benz stepped out of the Sauber shadow and, clad in AEG (part of Daimler-Benz) livery, they took on Jaguar head to head. The first race fell to them, but the series and, at last, Le Mans went to Jaguar. Le Mans saw the works factory Porsches back in business, but despite a titanic battle, Jaguar took the victory. TWR’s US team were victorious at the Daytona 24-Hours and the Sebring 12-Hours, giving Jaguar a clean sweep of the top-line endurance races that year.

GROUP C2: JUNIOR SCHOOL

From the earliest days of Group C, one of its strengths was the C Junior, later C2 class. Cars tended to be slightly smaller, less powerful, weirder-looking in some cases, and crewed by drivers lower down the pecking order. This enabled privateers to enter on a small budget and swell the fields to sensible numbers. The downside was that C1 drivers might complain of slow and erratic C2 drivers, but it was a two-way street, and it was not unknown for C1 drivers to push C2 cars off the track if they felt that they needed the bit of road the C2 was on.

The Mako Team’s C2 3.3-litre Cosworth DFL V8-powered Spice-Fiero SE88C of Don Shead, Robbie Stirling and Ross Hyett came 16th at Le Mans in 1989.

C2 was discontinued in 1990 when the FIA decided that privateers would be much happier running cars with F1 engines. Even top C2 teams like Spice, Gebhardt and Ecosse could not hope to compete with factory-backed operations such as Mercedes and Jaguar for outright honours, so they quietly moved on to other racing projects or went into liquidation.

CHAPTER 2

MAKES AND MANUFACTURERS

The decade encompassing Group C – effectively from 1982 to 1992 – attracted several top-line manufacturers, including Ford, Porsche, Lancia, Mercedes-Benz, Jaguar, Nissan, Mazda, Toyota and Peugeot, all of whom hosted competitions departments or racing teams, along with a host of smaller commercially run and privateer squads that made up the bulk of Group C2, of which Spice Engineering, Ecurie Ecosse and Tiga were the most prominent. The works teams hired the best drivers available, and, in respect of long-distance racing, Porsche already had the best of them on its roster. So, it is not surprising that Porsche was, overall, the most committed and consistently successful team, certainly in the first half of the 1980s. The following alphabetical cross-section of participating makes is packed with smaller ventures bent on resounding success, most of whom occupied the Group C2 category that came into being in 1983 and lasted until 1990. The appendix contains a complete list of participating teams.

The Sauber-Mercedes C9 driven by Kenny Acheson and Mauro Baldi won the Brands Hatch 480km, the fourth round of the 1989 WEC.

ADA ENGINEERING

Chris Crawford and Ian Harrower created ADA Engineering in 1977. Getting their start as an engineering design and consultancy firm, they ran a Gebhardt C2 in the World Endurance Championship in 1985, having some success the following year with a class win in the Le Mans 24-Hours. ADA chassis 88-02 was built in 1987 and debuted at the Brands Hatch 1,000km. In a practice session for the Kyalami 1,000km in South Africa the car driven by Michael Briggs and Mario Hytten was quickest C2, but was destroyed in a huge startline accident. It was rebuilt in 1988 with some modifications, resulting in ADA C2-02B, with chassis 03 entered in the World Sportscar Championship in 1988. Harrower entered the 1988 24 Hours of Le Mans with co-drivers Jiro Yoneyama and Hideo Fukuyama finishing 18th overall and claiming 2nd place in C2.

ALBA

Alba was a small Italian company based in Moncalieri near Turin, founded in 1982 by Giorgio Stirano, a former Osella engineer. The carbon-fibre composite AR2 was built to compete in Group C Junior powered by a four-cylinder 1.8 turbocharged engine. Martino Finotto and Carlo Facetti debuted it at the 1983 WSC event at Silverstone, winning Group C Junior. Another class win at the Nürburgring was followed by podium finishes in the UK and South Africa, earning Alba the Group C Junior title. In 1984, in quick succession, the Alba-Ford AR3, AR4, AR5 and AR6 were launched, but they could not match the previous year’s successes, with 8th in the 1985 Mugello 1,000km as their best result.

In play between 1990 and 1992 – though often a nonstarter – the Alba AR20 resembled its predecessors with its lobster-claw front end, although it was powered by a heavy 560bhp Motori Moderni 3.5-litre V12, designed by Carlo Chiti. The AR20 was driven by Marco Brand and Gianfranco Brancatelli with no notable success.

ALD AUTOMOBILES

ALD was the creation of Louis Descartes, a keen motor racing enthusiast who had begun his career in the French Hill Climb Championship driving such diverse cars as a Renault 8 Gordini and a Lola T298. The director of a public relations company from Levallois-Perret in Northwest Paris, Descartes formed his own racing team, ‘Automobile Louis Descartes’ (ALD) in 1984. Jean-Paul Sauvée was recruited to design and build a new Group C2 car for the team. Based around a conventional sheet-aluminium monocoque, the first ALD was powered by an ex-Schnitzer BMW M1-style, M80 3.5-litre 440bhp six-cylinder engine. The ALD ‘01’ made its debut at Le Mans in 1985, driven by Louis Descartes himself, Jacques Heuclin (the mayor of Seine-et-Marne) and Daniel Hubert, who had designed the car’s bodywork. As a small private constructor, the team did well to make the finish line of the 24-hour race.

Between 1986 and 1988, ALD continued to develop the original car and produced chassis ‘02’, ‘03’ and ‘04’. All were BMW-powered, and most of the C2 WEC/WSC rounds were entered. In 1989, chassis numbers #05 and #06 were built as customer cars for Didier Bonnet, while a new works car was constructed using a carbon-fibre/honeycomb chassis powered by a 3.3-litre Ford-Cosworth DFL V8. Designated ‘C289’, the car represented a quantum leap forward technologically and was campaigned in all the WSC rounds of 1989, including the Le Mans 24-Hours.