14,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Exisle Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

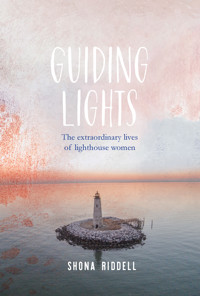

Women have a long history of keeping the lights burning, yet their stories are little known. Guiding Lights includes stories from around the world, as we discover the heroism of female lighthouse keepers, how they came to be hired (especially in the 19th century), and the mysteries and legends that are inextricably part of lighthouse history.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 298

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

GUIDINGLIGHTS

The extraordinary lives oflighthouse women

SHONA RIDDELL

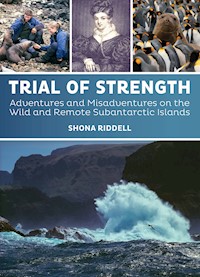

PRAISE FOR SHONA RIDDELL’S PREVIOUS BOOK,

TRIAL OF STRENGTH : ADVENTURES AND MISADVENTURES ON THE WILD AND REMOTE SUBANTARCTIC ISLANDS

‘Beautifully illustrated, this is a fascinating story of unique plants and wildlife, wild weather and tenacious explorers.’

— Grass Roots magazine

‘Riddell writes in a way that will both engage people who know little of the islands and evoke a sense of place for those who have been there.’

— Otago Daily Times

‘ … kept me glued to the pages from beginning to end.’

— Booksellers NZ

‘Her richly illustrated book is a lively study of the ecological and human history of these wild but unquestionably fascinating places. Riddell has a gift of revealing the personalities who arrived — willingly or otherwise — on these remote shores.’

— The Listener magazine

'Every page of this delightful book brings a new story ... every photograph a feast for the senses.'

— Nimrod: The Journal of the Ernest Shackleton Autumn School

‘What a great book … a rich and fascinating human history.’

— Afloat magazine

‘A wonderful, wonderful book ... introducing us to a part of the world that many of us probably didn't even know existed.’

— ABC Nightlife

‘I was impressed and delighted ... a highly recommended read.’

— Grownups.co.nz

First published 2020

Exisle Publishing Pty Ltd226 High Street, Dunedin, 9016, New ZealandPO Box 864, Chatswood, NSW 2057, Australiawww.exislepublishing.com

Copyright © 2020 in text: Shona RiddellCopyright © 2020 in photographs: as listed on pages 219–222

Shona Riddell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

All rights reserved. Except for short extracts for the purpose of review, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, whether electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher.

A CiP record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia.

Print ISBN 978 1 925820 62 1ePub ISBN 978 1 77559 461 1

Cover design and internal concept by www.bookdesigners.coInternal typesetting by Enni TuomisaloTypeset in Minion Pro, 10pt

DisclaimerWhile this book is intended as a general information resource and all care has been taken in compiling the contents, neither the author nor the publisher and their distributors can be held responsible for any loss, claim or action that may arise from reliance on the information contained in this book.

For Richard, Ruby and Violet.My beacons.

‘Steadfast, serene, immovable, the same Year after year, through all the silent night Burns on forevermore that quenchless flame, Shines on that inextinguishable light!’

— Henry Wadsworth Longfellow,‘The Lighthouse’, 1849

‘Few women have witnessed storms she has seen. Upon those danger spots, where the streaming light throws its guiding beam over the night-bound sea, the forces of wind and water vent their strength and fury unrestrained.’

— ‘The Lady of the Lighthouse’,The Sydney Mail, 3 August 1927

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

A world apart

1. WATCH-FIRE’S LIGHT

The origin and evolution of lighthouses

2. DAY AND NIGHT

The role of a keeper

3. MODEST YET SO BRAVE

Grace Darling and Ida Lewis

4. KEEPING HER LAMP ALIGHT

The lives of female keepers

5. CEASELESS VIGIL

The impact of isolation

6. WHISPERS OF THE PAST

Ghosts, legends and mysteries

7. LONELY OUTPOSTS

Lighthouse women in the twentieth century

8. THE TURNING OF THE LIGHT

Today’s keepers and caretakers

Epilogue: To the lighthouse

Acknowledgements

Bibliography

Image credits

Endnotes

Appendix: The lighthouses of Guiding Lights

Index

‘A light here required ashadow there.’

— Virginia Woolf1

INTRODUCTION

A world apart

From darkness to light, light to darkness. Lighthouses are a curious contradiction: they symbolize hope and trust, but also solitude and hardship. These remote beacons have saved thousands of lives over the centuries and provided comfort to those on ships and on land, steadily blinking their lights across the ocean. Yet many of them now sit empty, cloaked in legend and mystery, with sorrowful tales of solitary keepers perched on sea-ravaged coastlines.

If you live in a coastal town, you probably live near a lighthouse. From the hills surrounding my seaside home in Wellington, New Zealand, I can look across the harbour entrance to the old Pencarrow Lighthouse, a small white tower perched on the headland. Its light hasn’t shone since 1935 but it is a maintained historical site, a daymark for ships and an integral part of the city’s landscape. First lit on 1 January 1859, it was New Zealand’s first permanent lighthouse and the home of Mary Jane Bennett, New Zealand’s first — and only — female lighthouse keeper. A widow with six children (another had died in infancy), she took over her late husband’s job and efficiently managed the light for ten years.

Mary was the inspiration for this book, and her story can be found in Chapter 4. I wanted to know why she was the country’s only female keeper and if there had been many others around the world. My curiosity has taken me on a (metaphorical, low-carbon) journey through the centuries and around the globe, to some of the world’s most fascinating towers.

WOMEN’S WORK

Stories of female lighthouse keepers are not new. In the United States, for example, there have been female keepers in sole charge of lighthouses since at least the late 1700s. From 1820 to 1859 at least 5 percent of principal keepers employed by the federal government were women (more than 200 women were also appointed assistant keepers during the nineteenth century), most of whom received equal pay to their male counterparts, and several also had male assistants — all of which seems astonishing when we recall that this was almost 100 years before American women were allowed to vote.2

These women performed difficult work in extremely challenging conditions — night and day, all year round, through storms, blizzards and even hurricanes. They saved sailors’ lives, indirectly by keeping the light burning to enable the safe passage of ships, and also by rowing out into thrashing surf to rescue crew and passengers in peril. Yet it is only in the past few decades that work has been done to acknowledge most of these women and share their stories. How did they become lighthouse keepers? Why were they appointed during such a conservative era, when women were generally employed as domestic servants or seamstresses (if they were in paid employment at all)? And why, despite the often glowing reports these women received from lighthouse inspectors, were women in the twentieth century rarely appointed as principal keepers?

Most of the written history of lighthouses focuses on men. Lighthouses were usually commissioned, built and administered by men, and it is important to share this background to provide context for the keepers. Without these enduring structures, there would have been no one to run them (or men to ‘man’ them, as the verb indicates). But women played an early role too, from lighting coastal fires to royal lighthouse administration. From the late 1800s keepers also kept daily written logs, which reveal female keepers’ experiences in their own words.

There are many excellent books on lighthouse history in the United States, particularly Mary Louise Clifford and J Candace Clifford’s Women Who Kept the Lights (first published in 1993) and Eric Jay Dolin’s Brilliant Beacons (2016). However, most lighthouse history books tend to focus on one lighthouse, one state or one country. I wanted to bring together stories from around the world to illustrate how women’s experiences varied depending on the era, their circumstances and the location.

Most of the historical information available about lighthouse women comes from North America, the United Kingdom, and Commonwealth countries such as Australia, Canada and New Zealand. Where possible I have cast the net wider, to include stories from Europe, Japan and South America, for example, but these are only representative. This book does not contain a list of every single female keeper or assistant keeper, nor is it exclusively about lighthouse keepers. I have written about women whose lives were shaped by lighthouses: not only female keepers, but also male keepers’ wives and daughters. Throughout the nineteenth century many women assisted their husbands, brothers or fathers, carrying out a keeper’s job in every way but in title. They were not named, paid or publicly acknowledged, but their stories are important. In the twentieth century most lighthouse women were keepers’ wives who kept the station running, providing stability and supporting their husbands in their isolated work.

Today we have ‘caretakers’, women who are not trimming the wicks but are still looking after lighthouses. For example, they volunteer to live on Australia’s remote Maatsuyker Island (home to the country’s southernmost lighthouse) because they relish the opportunity to contribute, to enjoy freedom and nature, and have a ‘pioneer’ experience. It is a shorter assignment than it used to be, with half-yearly rotations, and usually couples taking the job. It is also less isolated (to a degree), with helicopter deliveries and internet access. Meanwhile, for the men and women of the Canadian Coast Guard, lighthouse keeping is still a long-term career option. See Chapter 8 for stories of women who live and work at lighthouse stations today.

It has been fascinating and revealing to learn how lighthouse women were represented by journalists, artists and poets over the centuries. Sometimes they were revered with flowery prose; sometimes they were patronized; sometimes they were ignored altogether. (Of course, female writers had their own voices.) I have included snippets of old newspaper articles, poems and stories throughout the book as snapshots of how these women, and lighthouse keepers in general, were perceived at the time. They are windows into the past, as are the tales of lingering lighthouse spirits, which, whether or not you believe in paranormal activity, were generally inspired by historical events.

CONNECTIONS TO HOME

New Zealand is a small, isolated country. It was once heavily dependent on transportation by sea, and, unfortunately, before the 1850s a combination of wooden ships, poorly charted rocky coastlines, intoxicated or inexperienced skippers and a lack of navigational aids often proved a recipe for disaster. There have been thousands of shipwrecks en route to New Zealand or along its coastline since European immigration began in the 1790s; one, the Cospatrick in 1874, resulted in the deaths of 470 passengers.3 Lighthouses were vital for the safe passage of ships and today there are still 23 active lighthouses and 74 light beacons lining the coasts. After all, shipwrecks still occur: the sinking in Wellington Harbour of the Wahine ferry in 1968 resulted in 53 deaths; in the Marlborough Sounds, the Soviet ocean liner Mikhail Lermontov sank in 1986 with all but one of its 738 passengers rescued; and in the Bay of Plenty the container ship Rena spilled its oil cargo in 2011, resulting in what was considered the country’s worst maritime environmental disaster.

Castle Point Lighthouse as seen from the beach.

Sunset at Castle Point Lighthouse.

One of New Zealand’s active lighthouses is in Castlepoint, or Rangiwhakaoma (‘where the sky runs’ in Māori). Its English name originated in the late 1700s with Captain Cook, who was inspired by what he called its ‘remarkable hillock’. Castlepoint is a tiny coastal settlement in the Wairarapa region with an elegant, Edwardian lighthouse (Castle Point Lighthouse) perched on the peninsula. Despite its elevated position 52 metres (170 feet) above sea level, the tower is splattered by giant waves in wild weather and the narrow track from the beach becomes almost impassable. On a fine day, it is a scene that has decorated many postcards, and I spent several childhood summers playing on the beach and visiting the lighthouse. Living near the bottom of the world, I have a long-held fascination with the sea, remote locations and solitary professions (writing books is very solitary, but not as solitary as lighthouse keeping). I am not a lighthouse tourist per se — I don’t globetrot with a checklist — but I enjoy escaping into their stories, both real and fictional.

A family connection also makes history resonate more deeply for me, as readers of my other books will know. While writing Guiding Lights I learned that one of my ancestors, a great-great aunt named Margaret Hughes, married William Bennett, the youngest son of keeper Mary Bennett. William was born at Pencarrow Lighthouse in 1855, six months after his father drowned. He lived there until he was ten, when the Bennett family sailed to England. The southerly roar of the Cook Strait must have stayed with William, because he returned to New Zealand as an adult and became assistant keeper at the same lighthouse from 1880 to 1885.

Another relative, John Frederick Rayner, was a lighthouse keeper for more than 40 years. From 1902 to 1906 he was stationed at Puysegur Point, first lit in 1879 and one of New Zealand’s most remote lighthouses. Bleak, barren, difficult to reach, plagued by sand flies and exposed to the frigid winds of the Southern Ocean, Puysegur Point in Fiordland was considered the country’s toughest family station and almost a penal sentence for keepers. Sheep and chickens were blown off the steep cliffs during the frequent gales, and relief keepers undertook a daring ‘initiation’ in which they crawled to the cliff-edge and leaned into the void, the arms of their oilskin coats extended like bat wings, saved from a plummeting death only by the brute force of the southerly wind. According to family legend, John Rayner’s recorded wind measurements were not taken seriously by the lighthouse service until one of the country’s first anemometers was installed there and his calculations were verified. (The highest wind speed on record at Puysegur Point was 183.5 kilometres per hour — 100 knots — in 1995, but as that was the maximum speed the instrument was capable of measuring, the unrecorded maximum is likely to be considerably higher.4)

Through the twentieth century, life at Puysegur Point was a struggle for many keepers and their families. One assistant keeper begged for a transfer in the 1930s, claiming both he and his wife were suffering from rheumatism due to ‘the very damp climate here, together with the absence of fresh fruit and vegetables, milk and meat’.5 There were more challenges to come. In 1942, the 12-metre (40-foot) tall wooden lighthouse was razed in a fire. At first locals thought the inferno was the result of a wartime air invasion — but it turned out to be arson by a man from nearby Coal Island, who objected to the periodic sweep of light into his bedroom while he was trying to sleep. He rowed out to the point in the dead of night, held two keepers and their families hostage with a rifle, destroyed their radio telephone and set the lighthouse on fire. One keeper was knocked unconscious during the incident (described as a ‘Lighthouse Sensation’ in subsequent newspaper headlines) and the lighthouse was destroyed. Its replacement was a 5-metre (16-foot) concrete tower. The culprit, described in the official report as ‘a demented person, a hermit of the area’, was arrested on Coal Island after a police manhunt and was institutionalized.6

The old lighthouse ablaze after arson at Puysegur Point, 1942.

Puysegur Point.

ROMANTIC, CHILLING, DRAMATIC OR COMFORTING?

Old lighthouses are often described as romantic locations, but were they? It’s easy to imagine a beautiful nineteenth-century woman standing on a clifftop in front of a lighthouse, her long skirts billowing in the darkening dusk as she looks out to sea. A Cathy Earnshaw or Scarlett O’Hara of the light, perhaps. Of course, there would have been some romance in the thousands of towers dotted around the globe, but most of the stories I’ve read have been more pragmatic than fanciful. Their themes centre around isolation, pride, paperwork, duty, dedication, bad weather, accidents, rescues, raising children and the effects of cabin fever (or island fever, in this case).

Lighthouses are also perceived as lonely outposts, and keepers’ families were often questioned about this aspect by newspaper reporters, but many maintained there was little time for loneliness. They also derived pleasure from being surrounded by nature, the ever-changing view of the sea, the moods of the weather, their independence and the pride they took in their work. As most of us know, bustling cities can feel equally lonely, and the constant hum of populated towns isn’t for everyone. For example, keeper Kate Walker of Robbins Reef, New York, declared in the early twentieth century that she would rather live alone at her sea-surrounded lighthouse than in a million-dollar mansion on the mainland.7

It is certainly the dramatic tales that generate the most interest and I must admit that I am not exempt from being drawn to drama. Thus I have included several gripping yarns of murders, accidents and similarly wild and uncanny events from bygone eras in the book. I am also interested in the physical and mental effects of living in isolated locations, particularly the finer details (Where did a keeper’s wife give birth? Why was mercury included in a lighthouse medical kit?). But we must remember that for every day of wild storms and lives in jeopardy, there would have been many more days of quiet, uneventful routine. After all, routines provided much-needed comfort and stability in highly unusual circumstances.

The Lighthouse Keeper’s Lunch. First published in 1977, this famous children’s book features Mr and Mrs Grinling and their cat, Hamish. Mr Grinling is the faithful keeper who constantly gets into scrapes and it is clear from the series that he couldn’t manage without his practical and industrious wife.

Whether famed for their comforting lights or their dark pasts (or both), lighthouses have certainly captured the public’s imagination over the centuries. They have inspired some of the world’s most celebrated art, including paintings (Hopper, Turner), poems (Wordsworth, Coleridge), short stories (Poe), children’s books (The Lighthouse Keeper’s Lunch), novels (The Light Between Oceans, To the Lighthouse), ballads and films (often unsettling horrors/thrillers such as The Lighthouse).

La Jument, France. This iconic photo was taken by Jean Guichard from a helicopter in 1989. The resident keeper can be seen at the entrance.

From the late nineteenth century the general public were able to capture lighthouse images for themselves, thanks to Kodak portable cameras, and also collect mementos such as lighthouse postcards and pictures from cigarette packs (known as tobacco cards) with trivia about lighthouses. More recently high-res photography, livestreaming and helicopter or drone footage have shown the scale of fearsome waves battering solitary towers (as per Jean Guichard’s iconic ‘La Jument’ photos). These examples not only illustrate our ongoing fascination with lighthouses, but they again show the contrast between their hope/fear symbolism. Are lighthouses comforting or menacing? Both, it would seem.

A GLOBAL LEGACY

There is something about lighthouses that transcends location and language. Right from the start, when I told people that I was writing a book about lighthouses their faces would (forgive the pun) light up. I think most of us have a ‘favourite’ lighthouse, whether we’ve visited it or not.

Many lighthouses are still active, though most are now automated. Despite developments in technology they continue to be a navigation aid for ships and a comforting sight in the darkness. But as lighthouses become obsolete, some are abandoned or demolished — or destroyed by the nature that surrounds them. The march of time, coastal erosion and climate change all threaten lighthouses, with rising ocean levels and storms growing in intensity. For example, Kiipsaare Lighthouse in Estonia was built inland, but it is now surrounded by the sea and on a precarious lean.

However, it’s not all doom and gloom for lighthouses. Maritime organizations and preservation groups restore and maintain many old towers, keeping them standing for us to visit, learn from and appreciate. Through travel, social media hashtags (see #lighthousesoftheworld on Instagram), documentaries, websites and books we can still enjoy the lure and lustre of lighthouses, noble beacons surrounded by the sea. But they are more than just pretty pictures. We can keep their stories alive, too.

Shona Riddell

2020

‘Welcome, welcometorch of the night!Your light shines like a fulsome,glorious day!’

— Aeschylus’ Agamemnon, 458 BC1

1

WATCH-FIRE’S LIGHT

The origin and evolutionof lighthouses

Women have always tended to the lights in one form or another. In ancient times, tending to a domestic or altar fire was generally a woman’s domain. Hestia, Greek goddess of the hearth, was responsible for maintaining the family fire on Mount Olympus, which she fed with fat deposits from the mortals’ many animal sacrifices to the gods. Hestia’s Roman equivalent was Vesta, whose sacred altar flame was tended by six virgin priestesses selected for 30-year terms of service. The Vestal Virgins were revered and believed to hold magical powers. It was indeed a privileged position — as long as they didn’t break their vows of chastity or service.

The Assassination of Agamemnon, an illustration from Stories from the Greek Tragedians by Alfred Church, 1897.

Guiding lights for mariners have also existed for thousands of years, providing hope and security in the middle of black, tempestuous oceans. The first coastal beacons were bonfires, an early example of which was shared by the bard Homer in his epic poem The Iliad, circa 750 BC:

‘As to seamen o’er the wave is borneThe watch-fire’s light, which, high among the hills,Some shepherd kindles in his lonely fold.’

Nocturnal fires were lit to guide vessels, to convey messages — and sometimes to entrap unsuspecting husbands. At the end of the decade-long Trojan War, King Agamemnon of Mycenae lit a series of beacon fires to announce the Greeks’ success to his wife, Queen Clytemnestra, who then lit her own series of fires to guide him home and relay the message of his imminent return. After a triumphant arrival and a seemingly warm welcome, Agamemnon had a bath to recover from his long journey. However, the moment he emerged, Clytemnestra and her lover smothered, stabbed and beheaded him. (In Clytemnestra’s defence, Agamemnon had sacrificed their daughter Iphigenia to the gods before heading off to war, so there was some history there.)

The Sirens and Ulysses by William Etty, 1837.

Women, or at least mythical female forms, were also blamed for sailors’ deaths and shipwrecks as a cautionary tale to illustrate the dangers of the sea. In this case, the bewitching song of the Greek Sirens (birdlike women) allegedly drove men to wreck their ships on island reefs. Odysseus of Thebes, who was also making his way home after the Trojan War, instructed his men to block their ears with beeswax and tie him to a mast so he could safely experience the Sirens’ alluring call. Thus captivated, he begged his men to untie him (they didn’t). Two thousand years later, female figures reclining on rocks were still distracting sailors. In 1493, for example, explorer Christopher Columbus reported seeing three mermaids near the Dominican Republic.2

The world’s oceans can undoubtedly be dangerous and unpredictable (perhaps more so because of pirates, reefs and storms than fantasy creatures), and as long as there have been ships and shipwrecks, there has been a need for guiding lights. However, while blazing bonfires on ancient hills served a practical and noble purpose, strong winds and lashing rain would have constantly threatened their flames, not to mention chilled the lonely watchmen. As a solution, towers began to be built to keep the fires burning more reliably.

The world’s first ‘lighthouse’ as we know it, a tower with an enclosed flame, was first lit in 280 BC. The Pharos of Alexandria stood on a small island near the city’s harbour entrance. The lighthouse would have been an eye-catching structure in its day: more than 100 metres (330 feet) tall, it was elevated on a base of thick stone and had three levels: one square, one octagonal, and a cylinder at the top enclosing a furnace. Its stone exterior, possibly limestone or granite, displayed elaborate carvings, and statues of Greek gods were placed at the top. Construction took twelve years at a cost of 800 talents (one talent was equal to more than 23,000 kilograms or 23 tonnes of silver) — an extravagant price for the time.

The precise motives behind the tower’s construction are debated; possibly it was built purely to guide ships into port (Alexandria attracted the world’s greatest thinkers and innovators; the London, Vienna or Silicon Valley of its time), but some historians believe it was also a narcissistic commission by Alexandria’s Macedonian ruler Ptolemy I, who wanted to create a symbol of his power and nobility. If so, its architect had the last laugh — at least, according to one version of the lighthouse’s history. Sostratus of Cnidus, it was written, carved his own name deep into one of the walls, a subtly rebellious act that was exposed only after many decades had passed.

Two centuries later the Pharos was still active when Cleopatra, Queen of Egypt and a descendant of Ptolemy I, was rolled up in a carpet (according to the Greek writer Plutarch) and smuggled into the royal palace of Alexandria to meet Julius Caesar in 48 BC. Whatever the original reasons for its existence, and whatever love affairs, scandals and power plays occurred beneath its nocturnal gaze, the Pharos successfully guided ships into the port of Alexandria for almost 1000 years and remained as a daymark for a further 500 years. Eventually, invasions and several large earthquakes caused the downfall of what was considered one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. However, the lighthouse still lives on in the French word for lighthouse (phare), as well as Spanish and Italian (faro). A lighthouse expert is a Pharologist.

The Pharos was not the world’s only ancient lighthouse. In Spain, the Tower of Hercules was built in the second century AD by the Romans, and it still stands. The Romans also built wooden lighthouses during the same period, all of which now only exist on ancient mosaics and coins. Another famous tower, the Tour d’Ordre, was constructed at the top of a cliff in Boulogne on what is now French land, erected in AD 44 and commissioned by Caligula, a so-called ‘mad’ Roman emperor (possibly due to a physical illness, but whatever the reason he was reportedly unhinged and drunk on his own power). According to sources at the time, Caligula readied his troops by the shore and challenged Neptune, the Roman god of the sea, to a battle. When Neptune failed to appear, Caligula triumphantly declared himself the victor and an enormous lighthouse was constructed to commemorate the event.3 Built of brick and stone and considered remarkable for its time, the tower remained standing for 1600 years until the cliff on which it stood collapsed in 1644. A replacement tower was eventually built in the same area.

An archaeologist’s depiction of the Pharos in Alexandria, drawn in 1909 by Hermann Thiersch.

ENGINEERS AND PIONEERS

Despite the early adoption of light as a navigation aid for mariners, lighthouses didn’t become common landmarks for a very long time. From AD 1100, countries in Europe began trading with one another, which led to a growing need for beacons to warn ships of approaching dangers, ranging from natural hazards such as reefs, to wars and plagues.

Shipwrecks often preceded the construction of lighthouses. Warships in a Heavy Storm (Ludolf Backhuysen, c. 1695).

During the Medieval period coastal lights in Britain were often tended by monks who collected duties from passing ships. However, there is at least one historical record of women keeping the lights burning. In Ireland, the nuns of St Anne’s Convent tended a ‘lighthouse’ in County Cork for more than 300 years, from 1202 until about 1530, using lighted torches in one of the convent’s towers to guide ships into Youghal Bay.

According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, it wasn’t until 1622 that the term ‘lighthouse’ entered the English language. This reflects the gradual evolution of lighthouses from rudimentary beacons to more enduring structures, with stone edifices and glass-enclosed lanterns that could withstand the ferocious force of the sea in all weather. As the book Lighthouses and Lightships (1870) explains:

Whether the lighthouse-tower is situated on some wave- washed rock surrounded by a hungry sea, or on the summit of a conspicuous headland, the highest skill is exercised upon its construction, and it becomes, in many instances, a monument of the most brilliant architectural genius. Not, indeed, that it exhibits those beautiful features of clustered columns and lofty arches, or that elaboration of picturesque ornament, which delight us in the lordly mansion and the ancient cathedral; but that an equal perfection of art is revealed in its massive simplicity and impregnable solidity.4

In other words, staying upright was more important than aesthetics. A lighthouse had to ‘defy the assault of wind and rain’ and also remain visible in all weather. It wasn’t a simple brief, but several men are remembered today for their forward-thinking designs of ‘difficult’ lighthouses that influenced designers and architects for generations. For example, one of England’s first lighthouses was built on a hostile cluster of rocks named Eddystone, 19 kilometres (12 miles) southwest of Plymouth Sound. These jagged rocks were on a common passage route from France to England and struck fear into the hearts of sailors, causing untold shipwrecks — both on the rocks and also along the French coast by ships attempting to avoid the Eddystone Rocks.

Henry Winstanley’s Eddystone Lighthouse, England, an engraving c. 1860.

Notably, it took three attempts over more than half a century to build a durable lighthouse. The first Eddystone lighthouse was lit in 1698 and was the world’s first lighthouse to be completely exposed to the open sea. Designed by an eccentric painter named Henry Winstanley, it was an octagonal tower made of wood. The job took two years to complete; work could only be carried out during the milder summer months and even then the waves thrashed up to 60 metres (200 feet) high, making the site inaccessible for days or even weeks on end (also, at one point during construction, Winstanley was kidnapped by French privateers, but was quickly released upon King Louis XIV’s orders). Sadly, Winstanley and five other men at the lighthouse were swept away in 1703 by the Great Storm, a ferocious extratropical cyclone that hurtled across Europe and killed thousands of people.

Smeaton’s Eddystone Lighthouse, painted by John Lynn in the early nineteenth century.

The second Eddystone lighthouse, also made of wood but with a core of brick and concrete, was designed by a silk merchant and property developer named John Rudyard in 1709. In 1755 it was completely destroyed by fire after a spark from the lantern set the roof alight. One of the keepers, an elderly man named Henry Hall, was tossing buckets of water up at the flames when he accidentally swallowed a glob of molten lead that had fallen from the burning roof into his mouth. All three keepers were rescued from the lighthouse before it collapsed, but when Hall told a doctor what had happened to his throat the doctor didn’t believe him. It was only when Hall died several days later that the same doctor performed an autopsy and found a 200-gram (7-ounce) piece of lead in Hall’s stomach.

Bell Rock in dramatic seas, as painted in 1819 by Joseph Turner.

Bell Rock.

In the late 1750s, civil engineer John Smeaton designed the third version of the lighthouse. Smeaton’s innovative structure sloped inwards like a tree trunk to lessen the impact of the waves at its base. Its exterior was made of granite and included dovetail joints that resisted being pulled apart. The 18-metre (60-foot) tall tower still had waves crashing over it at times, but it lasted for a century until the rocks underneath it began to erode and it had to be replaced. (While Smeaton’s tower was strong, its light, apparently, was not: until 1810 the lighthouse boasted a chandelier with a few dozen tallow candles.)5 Smeaton’s tower also inspired the famous sea-shanty ‘Eddystone Light’, which begins with the lines: ‘My father was the keeper of Eddystone Light / And he slept with a mermaid one fine night.’

Another pioneer of design was Robert Stevenson, the first of the famed ‘Lighthouse Stevensons’ and grandfather of Treasure Island author Robert Louis Stevenson. Beginning with Robert senior, three generations of Stevensons were responsible for designing and constructing many of the lighthouses around the British coastline. A famous example is Bell Rock Lighthouse, a 35-metre (110- foot) tall tower in the wild North Sea, 18 kilometres (11 miles) off the coast of Scotland. Bell Rock is considered one of the greatest architectural achievements of its time. Built in almost unimaginable circumstances on a tiny reef that was often obscured by the tide, the tower became an example of what was possible in remote, hazardous locations. It must have been a project manager’s nightmare: the initial construction had to be done on land, then the pieces were dismantled and transported to Bell Rock, where work was only possible during the summer months, for a few hours a day before the tide came in.

During his absences from their Edinburgh home Robert wrote faithfully to his wife (and step-sister) Jean, and he urged her not to succumb to deep melancholy after three of their young children died of whooping cough in 1808 (only five of their nine children survived into adulthood).6 Bell Rock Lighthouse was finally completed in 1810, after three years of construction and several injuries and deaths. More than 200 years later, it still stands.

There are similar stories involving French lighthouses, which started to be built in more exposed conditions as architectural standards improved. One example is Ar Men Lighthouse near the island of Sein in Brittany, first lit in 1881 after fourteen grim, weather-disrupted years of construction, and nicknamed ‘The Hell of Hells’ by keepers because of its inhospitable location. Workers lay on their stomachs while tied to the rocks to avoid being washed away as they placed the first stones.7

Locations at the end of the world

Lighthouses were built where the need was determined to be the greatest — for example, a hazardous reef with a high frequency of shipwrecks, or a harbour entrance on a common passage route for ships. The need for lighthouses to be constructed in remote or prominent locations has resulted in some stunning landscapes. Famous examples include Cape Horn Lighthouse (which is still occupied; see page 185), Strombolicchio Lighthouse in Italy (perched on top of an exposed volcanic peak); Thridrangaviti Lighthouse in Iceland (built with the use of helicopters, surrounded by killer whales and described by Atlas Obscura as ‘an introvert’s haven’8); the fantastically named Muckle Flugga Lighthouse in the Shetlands; and Aniva Lighthouse in Russia, rumoured to have once been a nuclear-powered penal colony.

To determine the optimal position for a new lighthouse (on a cliff, on a coastline or even in the sea), a mathematical formula was used to calculate the minimum required height to ensure the lighthouse would be sufficiently visible. In waters that were too deep for lighthouses, lightships were placed: anchored boats with guiding lights, sometimes known as ‘floating lighthouses’. The first lightship on record was in the River Thames, London, in 1734, although there is evidence of lighted beacons on ships as far back as ancient Rome. Today, lightships have mostly been replaced by automated buoys.

LIVING IN A LIGHTHOUSE