11,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: WS

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

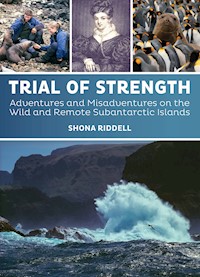

The subantarctic islands circle the lower part of the globe below New Zealand, Australia, Africa and South America in the ‘Roaring Forties’ and ‘Furious Fifties’ latitudes. They are filled with unique plants and wildlife, constantly buffeted by lashing rain and furious gales, and have a rich and fascinating human history. Trial of Strength tells the compelling stories of these islands and will leave you with an appreciation for the tenacity of the human race and the forbidding forces of nature.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 369

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

'They're not covered in ice, but they can be brutally cold. Despite our globalized, 21st-century world of frequent flying, they are rarely visited. Most of them are uninhabited by humans, yet they are teeming with wildlife.'

The subantarctic islands in the Roaring Forties and Furious Fifties latitudes circle the globe above Antarctica. They are buffeted by wind and rain all year round, and are full of exotic plants and animals.

Sometimes known as the 'forgotten islands' due to their remoteness, New Zealand's and Australia's subantarctic islands are protected World Heritage sites, recognized globally for their unique environments. The islands have also had their share of human visitors over the centuries, including intrepid explorers, plundering sealers, optimistic farmers, isolated astronomers, desperate castaways, wartime coastwatchers, pioneering scientists, and adventure tourists.

Written by a descendant of two subantarctic settlers from Britain, and featuring stunning photographs, Trial of Strength brings these historical tales to life for a 21stcentury audience, while inspiring a lasting appreciation for some of the most remote parts of our planet.

First published 2018

Exisle Publishing Pty Ltd

226 High Street, Dunedin, 9016, New Zealand

PO Box 864, Chatswood, NSW 2057, Australia

www.exislepublishing.com

Copyright © 2018 in text: Shona Riddell

Copyright © 2018 in images: refer to the Photographic Credits on page 248

Shona Riddell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

All rights reserved. Except for short extracts for the purpose of review, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, whether electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher.

A CiP record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand.

Print ISBN 978-1-77559-356-0

ePub ISBN 978-1-77559-393-5

Designed by Nick Turzynski of redinc. Book Design

Typeset in Minion Pro 12/15

For Sarah Ann Cripps (1822–92), my great-great-great grandmother and a reluctant seafarer with a heart of gold.

CONTENTS

Introduction

1. Discovery: The sealing captain, the 'ship's wife', and the lonely ghost (1780–1830)

2. Exploration: The polar explorers, the captain's wife, and the botanist with a secret (1760–1840)

3. Maungahuka: The warriors and the slaves (1842–56)

4. Hardwicke: The small town at the end of the world (1849–52)

5. Shipwrecks: The Grafton, the Invercauld and the General Grant (1864–67)

6. Transit of Venus: The astronomers, the photographers, and the epic poem (1874–75)

7. Wreck-watch: Provisions depots and castaway rescue missions (1865–1927)

8. Pastoral leases: The optimistic farmers and the isolated sheep (1874–1931)

9. 'Cape Expedition': The enemy raiders and the wartime coastwatchers (1939–45)

10. Macquarie Island: The penguin oilers, the crusading scientist, and the expeditioners (1890–today)

11. Campbell Island Meteorological Station: The weather-watchers and the wildlife (1945–95)

12. Conservation: The sheep shooters, the teal tackle, and the subantarctic rangers (1960s–today)

13. Tourism: The minister, the comic artist, and the descendant (1968–today)

Acknowledgements

Appendix: Subantarctic island groups outside of the Antarctic Convergence

Endnotes

Bibliography

Photographic credits

Index

INTRODUCTION

THEY'RE NOT COVERED IN ICE, but they can be brutally cold. Despite our globalized, 21st-century world of frequent flying, they are rarely visited. Most of them are uninhabited by humans, yet they are teeming with wildlife. They are forbidding and fragile, bleak and beautiful. They are the world's subantarctic islands.

The subantarctic islands circle the lower part of the globe, below the southern tips of Australia, New Zealand, South America and Africa, forming a 'ring of tiny stepping stones'1 in the Roaring Forties and Furious Fifties latitudes encountered by those heading to Antarctica. But the subantarctic islands have no permanent ice on them and are warmer than their Antarctic neighbours, with plenty of wind, fog and rain caused by the colder Antarctic seas colliding with the warmer waters of the north.

Geographically and politically, the subantarctic is defined as the area north of the Antarctic Circle (the grey circle on the map on page 2) — in other words, the islands that lie between 47° and 60° latitude south of the Equator. But because of the subantarctic region's unique climate and environment, it's generally considered to be the area outside the Antarctic Convergence (the area outside the wavy blue line).

For the purposes of this book, 'subantarctic' follows the second definition and therefore excludes South Georgia Island and the Kerguelen Islands (considered 'Antarctic islands north of 60°S')2. What's more, the focus will be on New Zealand's and Australia's subantarctic islands in the Southern Ocean with the occasional leap across the globe to, say, the Falkland Islands in the South Atlantic Ocean, or the Crozet Islands in the Indian Ocean.

The 20-odd island groups in the subantarctic region appear on a world map as a series of tiny specks, surrounded and protected by vast, powerful oceans. Most of them are the remnants of ancient volcanic eruptions, and have been shaped over many centuries by glaciation and ocean currents. They contain some of the world's few remaining unspoiled environments, and are filled with unique wildlife and plants.

The human history of the islands

Despite their isolation and wild climates, these far-flung islands have been visited by countless people over the past two centuries — not always intentionally. Their stories feature births, deaths, greed, fear, triumph (sometimes) and endurance. The early arrivals hunted seals and whales; dozens of ships were wrecked there, leaving castaways to battle against the elements for survival; curious scientists and explorers ventured south with great enthusiasm; optimistic farmers leased the land; and wartime coastwatchers were ordered to keep a lookout for enemy ships.

There were even young families who sailed all the way from England to live there: the Hardwicke settlers of the mid-1800s. Two of them were my great-great-great grandparents, Isaac and Sarah Cripps. Their fourth child, my great-great grandmother Harriet, was born on Auckland Island, 465 kilometres (290 miles) south of New Zealand. It was, and still is, a very unusual birthplace.

For four generations the tale of the short-lived, ill-fated Hardwicke township has been passed down through my family. As a child, I was unmoved by the story; I assumed that the Auckland Islands were somewhere near Auckland City and hence not very exotic (at least, not to a New Zealander). But once I grew up and studied a world map, I wondered: What on earth were they thinking?

After all, what could possibly possess a British couple to sail halfway around the world in 1849 with their three young children, along with just 55 other people, to live in a place so utterly hostile, remote and (they thought) uninhabited? Their motives are explained, and their story is told, in Chapter 4.

A personal pilgrimage

Today, all of New Zealand's subantarctic islands are uninhabited (Macquarie Island is Australian territory and still has an occupied research station), although they continue to attract small numbers of tourists, scientists and conservationists from around the world.

I felt drawn to the islands too, even though the idea of sailing over storm-tossed seas seemed rather nightmarish. The titles of books I'd read on the subject weren't reassuring: Island of the Lost, Forgotten Islands, Islands of Despair ... One of the Auckland Islands is even called Disappointment Island! Perhaps curiosity simply got the better of me, or perhaps it's in my blood, but at the end of 2016 I took a deep breath and headed south to The Snares, the Auckland Islands, and Campbell Island.

I got there by ship, like my forbearers, and despite the modern comforts of warm, waterproof clothing and hot showers, riding the rolling waves of the Southern Ocean was far from a cocktail cruise (but that's part of the adventure). The experience changed me, but not in the way I'd anticipated; instead of feeling despair, I felt awed and inspired.

The otherworldly plants and curious wildlife were like nothing I had ever encountered before. The frothing surf pounding against jagged cliffs, and the fierce, stinging wind on my face were exhilarating. It was like travelling back in time to a pre-human era, with no crowds, no TVs, no Facebook, no cars, no cafes ... and I was surprised to find that I loved it.

Visiting the subantarctic islands was a life-changing experience for me, but I certainly wasn't the first person to feel as I did. As one interviewee for this book put it: 'The islands stay with you. It's like an invisible cord always tugging, making you want to go back. I think about them every day.' This is particularly true for the small but dedicated group of people who have spent significant portions of their lives working there, often in challenging conditions. When you're thrown together to sink or swim in a remote location (literally, in the more historic cases), bonds form pretty quickly. Mention the sea lions, the albatrosses, the penguins, or the giant megaherb plants, and there's an instant spark, regardless of whether people were there one year ago or 60 years ago.

Forgotten books on forgotten islands

I returned home talking constantly about the subantarctic islands, reading every book and article that I could find on the topic, and connecting with other people who had been there too, either for scientific or meteorological work or simply for an unusual holiday. There is a growing awareness of the subantarctic islands thanks to mainstream media coverage, nature documentaries, and social media photos and hashtags, although most people would probably still struggle to point them out on a world map.

But I soon realized that most books on the subject were out of print and filled with outdated information. Even the more enduring history books from the 20th century are now several decades old. Fergus McLaren wrote about the history of the Auckland Islands (originally a PhD thesis) 80 years ago, and Conon Fraser's classic, Beyond the Roaring Forties, was published in 1986 — more than 30 years ago.

Since the 1980s, the Campbell Island Meteorological Station has become fully automated and there have been large-scale pest eradications on most of the islands, which have caused dramatic changes. There have been accidents and world-first helicopter rescues, as well as the ground-breaking use of new technology, such as drones and GPS, to study wildlife in tricky-to-reach locations.

The growth of the internet also means that many old documents, articles and photos, once buried in dusty corners of libraries, have been digitized and are now accessible from anywhere in the world with a few clicks. From the comfort of our homes we can read 19th-century shipwreck reports, experience the life of a subantarctic shepherd from his 100-year-old diary, or view high-quality footage of a stranger's journey to one of the most remote parts of the world. Still, not everything is online. Many precious documents are still buried in descendants' attics or boxed away in archives, and nothing on screen or paper compares with listening to the first-person accounts of people who have lived and worked on the islands over the years.

During my research I also noticed that women's stories were few and far between, either mentioned in passing or not at all. There were certainly men-only eras, but plenty of women have visited, worked on, or even lived on the subantarctic islands — my ancestors among them — and continue to do so in the case of Macquarie Island. Where were their stories? I had to dig a bit deeper to find them and have included several in this book.

An intertwining of narratives

Because the islands are so small, it's probably not a surprise that the different stories and eras tend to overlap. Macquarie Island penguin harvester Joseph Hatch's illegal sealing gang rescued the Derry Castle castaways from the Auckland Islands in the 1880s; Campbell Island conservationists camped in the old World War II coastwatching hut in the 1970s; German astronomers enjoyed Christmas dinner with the Auckland Island farmers in the 1870s; everyone stumbled across old shipwreck remains; and a tourist (me) visited her ancestors' long-abandoned, 19th-century home in the new millennium.

Despite the islands' location in the Southern Hemisphere, these stories span the globe. British, American and French explorers, Shetland farmers, New Zealand Māori, Chatham Island Moriori, Australian gold miners, European astronomers, a Scottish princess (albeit a mythical one)... it's a cast of thousands. But to manage expectations (and keep the book light enough to pick up), this book does not include a list of every single person, ship, and event related to the subantarctic islands. Instead, it offers snapshots of some of the livelier stories involving people who made it there — and sometimes, like Frodo, back again.

I may well have omitted a significant figure or left out a story that's close to someone's heart, and many events are only summarized (especially the ongoing conservation work, which could easily fill a book in itself), but these stories are intended to enlighten those who may have never heard of the subantarctic islands, or who have heard something about them and want to know more. There's a list of resources included at the back for those who would like to learn more about a particular island, person, or era. The subantarctic islands are an often-overlooked part of our planet and they deserve to be studied in more depth for their incredible history and unique environments (New Zealand's and Australia's subantarctic islands are all UNESCO World Heritage sites, a sign of their global importance).

People vs. Nature

Initially I'd thought that, as a non-scientist, I should focus on the human history and leave nature in the background, but I soon realized that was foolish and also impossible. Nature is the main character in all of these stories, featuring as the protagonist or antagonist (and sometimes both). After all, over the past two centuries nature has either drawn people to the subantarctic islands or driven them away. These days it forms a protective bubble around the islands, with lashing rain, fierce gales, and ferocious seas guarding their fragile ecosystems from long-term intrusion.

However, we still have a responsibility to protect and care for them. The subantarctic islands are vital breeding grounds for millions of seabirds and thousands of seals. But shifting air and water temperatures, introduced pests, diseases and fisheries all pose a threat to the rare and endemic wildlife, which depend on the islands' unique environments for their ongoing survival.

The subantarctic islands are beautiful, dramatic, remote and fascinating specks in the ocean that have so far managed to outlast their ephemeral human history. To mangle a line from Shakespeare: people make their entrances and their exits, but ultimately Mother Nature takes centre stage.

Shona Riddell, 2018

Te Reo Māori

A note on the pronunciation of Te Reo Māori (Māori language) words in this book: Longer vowel sounds are indicated by a macron (a straight bar) above the vowel. Vowels are pronounced a ‘ɒ’ (as in 'apart'), e 'ε' (as in 'entry'), i (as in 'eat'), ο ‘ɔ ' (as in 'pork') and u ‘ʉ' (as in 'loot').3

1. DISCOVERY

The sealing captain, the 'ship's wife', and the lonely ghost (1780–1830)

IMAGINE THE EUPHORIA OF BEINGthe first person in the world to officially discover an island. Now, imagine that excitement doubled when you discover two islands within six months of each other — both of them covered in seals, and right in the middle of a sealing boom.

It's a tale of rampant exploitation that today makes conservationists shudder, but in 1810 it was a jackpot of top-division lottery proportions for British-Australian captain Frederick Hasselburg of Sydney, who had sailed south through the Roaring Forties to seek his fortune.

But wait ... was it Hasselburg, Hasselbourg, Hazelburg, or Hasselborough? These days no one seems quite sure how the intrepid captain’s last name was spelled. The transcription of surnames was not an exact science in the early 19th century, and even the captain himself altered the spelling at least once.1 If he'd named one of the two islands he discovered after himself, his surname may have been more accurately recorded for posterity. Instead, he claimed them both for Britain and dutifully named one 'Campbell's Island' after Campbell & Co., the Sydney sealing company that employed him, and the other 'Macquarie's Island', after the governor of New South Wales.

There's no surviving portrait of Captain Hasselburg, so let's imagine him for a moment as a 19th-century, subantarctic Chris Hemsworth, standing proud, legs astride, at the helm of his two-masted ship, clad in long sea boots and a heavy cloak. His dark hair ripples in the wind, and his expression is determined as he peers through a brass telescope and clutches a sextant.

The ship under his command, aptly named the Perseverance, pitches and rolls over the swells, its square sails cracking and rope rigging shuddering in the strong winds. On either side, giant petrels and wandering albatrosses surf the breeze, while frigid grey waves crash over the slippery wooden decks. Even today, the turbulent Southern Ocean is not for the faint-hearted. Waves regularly surge up 5 to 10 metres, or 15 to 30 feet — 23.8 metres (78 feet) is the highest on record, off Campbell Island in 2018.2 The captain's small, wooden-masted sailing ship would have bobbed along like a cork at the mercy of the gale-force winds that are so prevalent in the southern latitudes.

A Campbell albatross soars over the stormy Southern Ocean.

Captain Hasselburg was desperately seeking new sealing grounds because things hadn't been going well for him. His reports to Campbell & Co., his employer, were 'the reverse of cheerful'3 because his sealing endeavours around the coasts of Australia and New Zealand hadn't amounted to much — there was simply too much competition and he was barely covering the costs of running his ship.

According to J.S. Cumpston's meticulously researched 1968 book, Macquarie Island, at the end of 1809 Campbell & Co. sent the Perseverance south with Hasselburg and a gang of sealers on a search for new sealing grounds.4 However, journalist Robert Carrick, who was known for his entertaining but not always reliable historical accounts in the late 19th century, writes that the captain was visited in his dreams by an angel who whispered some coordinates in his ear.5

Cumpston's version seems more plausible, but either way the captain was about to go where no European man had gone before. He departed from Sydney in late October on an exploratory voyage deep into the Southern Ocean and, on 4 January 1810, he stumbled across his holy grail.

Campbell Island today, looking much as it would have when Captain Hasselburg discovered it in 1810 (apart from the Tucker Cove farm site), with a view over Perseverance Harbour.

Captivated by Campbell

Campbell Island (Motu Ihupuku in Maori) is the eroded remains of a shield (domed) volcano lying almost 700 kilometres (435 miles) south of New Zealand's South Island.

As Captain Hasselburg's ship approached, the crew's first glimpse of the island would have been of mist-shrouded, tussock-covered hills up to 550 metres (1800 feet) tall, rising abruptly out of the sea. It was probably raining, because it rains there at least 320 days a year.

The island extends over 112 square kilometres (43 square miles) and is covered in low dracophyllum scrub, often blown horizontal by the sharp, incessant winds. The captain arrived in January, so he would have seen the flowering of the giant-leafed megaherb plants that bloom yellow and purple in the subantarctic summer, adding a surprisingly tropical touch to a bleak landscape. A light falling of snow is not unusual at any time of the year.

Great albatrosses nest on the misty plateaus, stretching out their 3-metre (10-foot) wings and soaring over the clifftops towards the open sea. The coastlines are peppered with seals, as well as yellow-eyed and rockhopper penguins. But the sight of these peaceful creatures in January 1810 would not have evoked a tender response in the captain. Instead, he would have had multiple pound signs flashing in a thought bubble over his head as soon as he saw the fur seals.

OPPOSITE A New Zealand sea lion on Campbell Island, with Bulbinella rossii.

After sailing into the main harbour, which is 1 kilometre (0.6 miles) wide and cuts 8 kilometres (5 miles) deep into the middle of the island from the east, he and his crew quickly got to work and eventually filled the Perseverance with 15,000 furseal skins. (He was apparently less interested in what were later described as the 'worthless and obnoxious' sea lions.6)

The back of New Zealand's $5 note features Campbell Island, the megaherbs Bulbinella rossii (the yellow 'Ross lily') and Pleurophyllum speciosum (the purple 'Campbell Island daisy'), and the yellow-eyed penguin (hoiho).

The captain then departed on the Perseverance, leaving behind his gang of seven sealers with some empty casks for collecting seal oil and a few months' worth of provisions. He returned to Sydney at a leisurely pace to pick up more equipment, and somehow managed to keep his discovery of Campbell Island a secret. But while making his way back in July to pick up his sealing gang as promised, the captain stumbled across an even better prospect: Macquarie Island.

Mesmerized by Macquarie

Macquarie Island (now fondly known to the resident staff as 'Macca') is a narrow, rocky stretch of land, about 35 kilometres long and up to 5 kilometres wide (22 x 3 miles). Highly unusually, it consists of a portion of the earth's mantle that has risen above sea level in one of the roughest parts of the Southern Ocean. It is constantly blasted by gale-force westerly winds, and its nearest neighbour, Auckland Island, is more than 600 kilometres (373 miles) away. Rain lashes its coastline for most of the year and the mean annual temperature is 4.5° Celsius (40° Fahrenheit). There is no harbour, so sealing ships had to take their chances and hurriedly land their crews and supplies before the weather turned and they either got dragged onto the rocks or blown back out to sea.

The island was uninhabited on Captain Hasselburg's arrival in 1810. However, the first thing he noticed on the shingle beach was the broken-up ruin of an old ship that he described as being 'of ancient design'.7 It was an ominous welcome and proved that he wasn't technically the first visitor to Macquarie, but he would perhaps be the first to leave the island in one piece.

Despite the bleak conditions, Macquarie Island was a hugely exciting discovery for Captain Hasselburg, even more so than Campbell had been. In peak season the island's narrow beaches are filled with hundreds of thousands of fur seals, as well as tens of thousands of elephant seals. Millions of penguins also crowd onto its shores in the springtime — kings, royals (which are endemic to Macquarie), rockhoppers and gentoos — although penguins would not be exploited for another 80 years.

If only he could have kept the big news of his discovery to himself! Alas, the captain hurried back to Sydney and behaved in a highly suspicious manner.8 His sealing peers, most of them ex-convicts and more than a little savvy, knew immediately that something was up; after all, the captain had arrived back so quickly. What's more, he had just ordered a suspiciously large volume of salt (used for curing sealskin), his employer Campbell & Co. was urgently advertising in the local paper for a dozen more sealers, and the captain was planning on heading straight back out to sea again. He might as well have put a giant notice in the paper announcing that he'd found a profitable sealing location.

That night, a few of the sealers invited Captain Hasselburg to dinner and filled him with rum. 'We already know where your precious island is,' they bluffed. 'Your discovery is not a new one. However, let's all have a wager of £20 and whoever writes down the most accurate coordinates will win the money

The captain, described in later testimony as 'more than half-seas over' from drinking (in other words, pretty far gone but still upright), eagerly scribbled Macquarie's longitude and latitude (55°S, 159°E) with a bit of chalk.

'That's the correct answer!' the men cried in feigned disappointment, after taking a good look at the numbers. 'You win £20.'

Captain Hasselburg happily collected his cash and went home. But the other men were set to gain a lot more than that, as they well knew.

Plunder in the South Seas

Within just a few years of discovery the seals had almost disappeared from both Macquarie and Campbell islands, hunted to near-extinction by sealing gangs from locations as far flung as the United States and England. Everyone was desperate to make their fortunes by selling the fur, which was in particular demand in Britain for hats and coats, as well as in China for trimming ceremonial robes.9 The oil rendered from elephant-seal blubber also burned cleanly in lamps and was used for soaps and machine lubrication. (Penguins would become a target later in the 1800s for fur muffs and twine.)

Fur seals, elephant seals, leopard seals and sea lions were all there for the taking on the subantarctic islands, but there was little press about it at the time. Nobody wanted to disclose the seal-rich locations they found, and there were also laws in the early 1800s that prohibited vessels from operating too far south. As a result, there are few surviving records of such a hectic time in history.10

It was a brutal business. Sealers armed with clubs or knives would round up and slaughter tens of thousands of seals at a time — 100,000 skins are estimated to have been taken from Macquarie Island in just one season.11

Meanwhile, health and safety rules for the sealers themselves were non-existent. Small groups of men would sail south in wild seas, with the constant threat of being wrecked against the sharp rocks of remote islands that were mere specks in a vast ocean. The sealing gangs were dropped off with basic provisions in freezing, remote areas and told to expect a pick-up several months later. However, sealing employers were notoriously cavalier about returning at the agreed time and sometimes they didn't return at all.

The seal colonies weren't easy to locate. Sea lions on Auckland and Campbell islands frequent the bays during the summer months, but fur seals are shy animals that stick to remote, rocky areas on barely accessible coastlines. As a result, sealers would often be lowered from steep clifftops with ropes, armed with clubs and a week's provisions.12

Only the promise of good money and eventual respite must have sustained the sealers in such primitive conditions. The subantarctic climate was cold and exposed, and the men would sleep in caves for shelter, or make tussock or sod huts. Many died in accidents, from injuries, from exposure, or from starvation. In such wretched conditions, sealing and survival were the two priorities. As the Mariner’s Captain Douglass informed the Sydney Gazette after he visited Macquarie Island in 1822:

"The men employed in the [sealing] gangs appear to be the very refuse of the human species, so abandoned and lost to every sense of moral duty.'13

One of his contemporaries added more details to the grim picture:

'... Their long beards, greasy seal-skin habiliments, and grim, fiend-like complexions, looked more like troops of demons from the infernal regions, than baptized Christian men, as they sallied forth with brandished clubs ...'

Of course, such callous slaughter wasn't sustainable in the long-term. Seal pups and mothers were also targeted, and within a few years barely a seal could be found. The subantarctic islands were abandoned once more.14 The British explorer Benjamin Morrell didn't see a single fur seal in 1830 when he visited the Auckland Islands for a week,15 and by the time the British Hardwicke settlers arrived in 1849 the few seals dotted around the coastlines provided a bit of sport for hunting and little else.16 There was a short-lived sealing revival later in the 19th century, but nothing close to what it had been.

'His discovery proved to be his death-knell'

During the so-called 'fur rush' many sealing ships carried women, some of whom were collected for a fee from the New South Wales penal colony in exchange for their company They were known euphemistically as 'ships' wives'. Travelling with sealing gangs across the open sea was a risky and sometimes perilous experience; some women died at sea from the rough conditions, while others were sold on to other ships or simply abandoned en route.17

One such woman (or girl, as we would now call her) was Elizabeth Farr, who was only 14 when she perished. Elizabeth came from the harshest penal colony of all, on Australia's Norfolk Island, so she may have been a convict or the daughter of a convict. She was on board the Perseverance with Captain Hasselburg when he discovered Campbell and Macquarie islands in 1810. (The captain was married to a woman named Catherine, but they had separated.18)

By the time the captain finally got around to collecting his gang of sealers from Campbell Island, ten months after dropping them off, they were desperate for rescue, having run out of supplies many months earlier and surviving mainly on seal meat and albatrosses. Still, they were all alive and their barrels were successfully filled with seal oil, lined up on the shore for collection.

Transporting the barrels back to the Perseverance took several weeks, with progress hampered by bad weather. On one such day, 4 November, the captain leapt into a small boat with Elizabeth and five others to row to shore. On their way back to the ship they encountered a peculiar weather phenomenon known as a 'williwaw'.

Old whalers' slang for a sudden violent squall, a williwaw is a mini-tornado of rain and wind that swoops down the mountains at up to 240 kilometres (150 miles) an hour. The coldness of the high-altitude temperatures combined with the gravitational pull creates a mighty funnel that can overturn small boats and push ships backwards out of the harbour. Also known as katabatic winds, williwaws are common in the harbours of Campbell Island.19

This particular williwaw was so ferocious that the jollyboat flipped over and all six of its occupants were instantly flung into the freezing water. Captain Hasselburg drowned almost immediately, weighed down by his heavy cloak and high sea-boots ('which must have baffled every personal exertion ... necessary to his preservation lamented the Sydney Gazette). The island he had so happily discovered almost a year earlier proved to be his death-knell'.20

Fortunately Elizabeth Farr could swim, so she started making for shore. Meanwhile the ship's carpenter, James Bloodworth, tried to save the captain, but quickly realized that it was too late. Instead he turned to help a 12-year-old cabin boy named George Allwright, the son of a Sydney baker, but he too had briefly flailed about before disappearing under the water. By then Elizabeth was struggling to stay afloat, so James swam across to her and headed with difficulty to shore while carrying her on his back. But once he had dragged himself out of the water, spluttering and hauling her out with him, he discovered to his horror that she was dead. Elizabeth was buried onshore the next day, but the captain's body was never found. He had, perhaps fittingly, been consigned to a watery grave. It was later revealed that, despite the distinction of discovering two islands, Captain Hasselburg died in debt to his employer, Campbell & Co.21

Even the Perseverance was destined to have the harbour as its final resting place. Twenty years later, the ship was wrecked in exactly the same spot, with more loss of life, in what is now known as Perseverance Harbour. It is the only recorded shipwreck on Campbell Island.

The world's loneliest ghost

Elizabeth Farr is not the only woman believed to have met her end on Campbell Island, although in the case of 'The Lady of the Heather', the rough reality of 'ships' wives' has morphed into a more romantic tale of aristocracy and betrayal.

From the early 19th century, sealers and whalers reported seeing a solitary woman roaming the shores of Perseverance Harbour, wearing a tartan shawl and a bonnet. Could the mystery lady have been the unwanted grand-daughter of Bonnie Prince Charlie, sent across the world to live in exile until her death?

This version of the 'Lady of the Heather' story claims that the 'Bonnie Prince', whose real name was Charles Stuart, had an affair with a woman called Clementina Walkinshaw who followed him from Scotland to France. Clementina and Charles had a love child named Charlotte (that part is true), who eventually had her own daughter named Marie (also true).

Marie, according to the legend, was eventually accused of spying on the Scottish Jacobites on behalf of the British government.22 They wanted her gone yesterday, so Captain James Stewart (the source of Stewart Island's name in New Zealand) stepped up for the job. He'd always boasted of his close friendship with Charles Stuart, and was known to be somewhat of a rogue with loose morals.

In 1828 he dragged poor Marie onto his ship and set sail for New Zealand. However, he quickly decided that Stewart Island wasn't remote enough and carried on south for another 660 kilometres (400 miles) to Campbell Island, where he built the young woman a sod hut in Camp Cove and abandoned her to live in exile for the rest of her life.

Legend would have us believe that Marie tried to make the best of things. She created a white-pebbled path that led from her hut to the shoreline, planted some Scottish heather, and rang her Angelus bell each day (the Catholic call to prayer) as she waited in the vain hope of rescue. But poor Marie died within a year, and the ghostly form of the 'Lady of the Heather' now wanders (allegedly) over the lonely island in the moonlight, clad in her shawl of royal Stuart tartan and a Glengarry bonnet. If you listen carefully the next time you happen to be visiting Campbell Island, you might hear the faint ringing of the Angelus bell.

Sceptics will undoubtedly snort in derision and mutter that the whole thing is a farce ('That sound isn't the Angelus bell; it's the humming of my drone quadcopter!'). And it's true that the details don't quite add up — Charles Stuart's grand-daughter died in 1789, for one thing, before Campbell Island was even discovered. But there probably was a woman abandoned on Campbell Island, a non-princess who simply had some very bad luck. A female, subantarctic Robinson Crusoe who didn't fare quite as well.

After all, the British explorer James Clark Ross reported coming across a French woman's grave in 1840, although it might have been Elizabeth Farr's grave. Malcolm Fraser of the New Zealand government, who travelled to Campbell Island on the Hinemoa steamship in 1906 on the lookout for castaways, wrote of coming across a sod hut, the remains of a fireplace, and a pebble-lined path to the water. New Zealand surveyor and wartime coastwatcher Allan Eden also saw the same things when he visited Campbell Island in the early 1940s, and there are still signs of an old hut at Camp Cove.23 The non-native heather plant was definitely there, too; some of it was brought back to New Zealand in the 1950s.24

Whatever the real story, journalist Robert Carrick picked up on the legend (or possibly invented it) and enthusiastically perpetuated it in a Sydney newspaper in the late 1800s. The romantic fable was then expanded in Will Lawson's rather soppy 1945 novel, The Lady of the Heather, which features a gentle, stoic woman who is cared for by shy, kind-hearted sailors. The opening page paints a vivid picture:

'The scene before her eyes was wild indeed ... Above the little cove loomed bare slopes, surmounted by black basalt peaks, too smooth to hold the snow and reaching like fingers into the cloud-hidden skies. No more gloomy a place than this island fastness could be imagined in the light of the dying day ...'25

Invented or not, 'The Lady of the Heather' has become an indelible part of Campbell Island folklore and there is something quite compelling about a Scottish–French ghost princess wandering around a remote island in the moonlight. There have been no 'official' sightings recently; although, as one former resident put it, the odds of seeing her increase after a few glasses of brandy.

Living on The Snares

Women certainly weren't the only people abandoned on subantarctic islands in the early 1800s. Two hundred kilometres (125 miles) south of New Zealand lie The Snares (also known as Snares Islands, or Tini Heke in Māori), a small cluster of tiny islands named by British captain George Vancouver, who came across them in 1791 (Canada's Vancouver Island was named after him).

In his ship's log, Captain Vancouver described the islands matter-of-factly as craggy', and named them The Snares because of their potential to cause trouble for any ship that happened to be passing on its way from Australia to England. New Zealand Māori living on Stewart Island/Rakiura had already spotted The Snares lurking in the south and called the archipelago 'Te Taniwha' ('The Monster'). The islands are framed by forests of tree daisies and today are uninhabited apart from the wildlife, including Snares crested penguins, Buller's and Salvin's albatrosses, petrels, tomtits, fernbirds, and New Zealand fur seals.26

However, there was once a small group of very reluctant, long-term residents. In 1810 a group of four unfortunate men from the sealing ship Adventure were put ashore on The Snares and left there indefinitely. The captain had decided there weren't enough provisions on board to go around and the men, who are believed to have been ex-convicts from Norfolk Island, were shoved off the ship with their discharge papers. Perhaps the captain felt the islands' remoteness and emptiness made them a safer drop-off point than New Zealand. They were given a few handfuls of rice, half a bushel of potatoes and an iron pot, wished all the best of luck, and abandoned without a backward glance.27

What a miserable place to be left behind! These tiny islands in the middle of nowhere offered little chance of rescue, and constant wild weather. But in a cunning move that could have been inspired by the novel The Martian (if it had been published 200 years earlier), the men were smart enough to plant the potatoes, which fortunately managed to flourish during the seven years that they were forced to sit and wait for rescue. They also lived off the plentiful local birds and the seals.

An American whaling ship named the Enterprise, on a sealing voyage from Philadelphia to Sydney, sailed past The Snares in 1817 and discovered the stranded men. The ship's crew reported seeing an abundance of potatoes that covered at least half of the main island (the total area of The Snares is 3.5 square kilometres or 1.3 square miles). There were only three men left by that point. In the interim, the fourth man had apparently lost his mind from the isolation and discomfort. His odd behaviour unsettled the others, who dealt with the issue by pushing him off a cliff.28 Given the unusual circumstances, they were eventually pardoned.

Snares crested penguins.

Today, The Snares are once again uninhabited. They are considered one of the world's least modified pieces of land and a special permit is required to set foot on them. There is no longer any sign of the potatoes.29

2. EXPLORATION

The polar explorers, the captain's wife, and the botanist with a secret (1760-1840)

CAPTAIN ABRAHAM BRISTOWdid not have time for such frivolities as exploring new islands in August 1806. The whaling captain was making his way back to England after a southern voyage in his ship Ocean, owned by the British whaling and shipping empire Samuel Enderby & Sons. It had been a successful expedition and his vessel was laden with whale oil, a valued commodity for lighting at the time.

When he reached the 50th latitude south, a shadowy form emerged from the open sea. As he drew closer, Bristow saw that it was a group of islands, two large and many small, and previously unrecorded.1 Bristow immediately pulled out his captain's log and scribbled:

'This place I should suppose abounds with seals, and sorry I am that the time and the lumbered state of my ship do not allow me to examine.'2

He named them 'Lord Auckland's Groupe' after his father's friend William Eden, whose title was 1st Baron Auckland.

Bristow was the first European discoverer of the Auckland Islands. However, in 2003 archaeological evidence (including the remains of earth ovens, stone artefacts, and piles of bird, seal and fish bones) was found on Enderby Island, proving there was a shortlived settlement of Polynesians on the islands in the 13th or 14th century AD.3

The Auckland Islands (Motu Maha or Maungahuka in Māori) are the remnants of ancient volcanic rocks. There are two large islands, Auckland and Adams, separated by a strait of water called Carnley Harbour. Scattered around are a dozen smaller islands, including Disappointment Island (possibly named by an unimpressed Captain Bristow), Enderby Island, and Rose Island.

Auckland Island is by far the biggest of the group at 42 kilometres long and 15 kilometres wide (26 x 9 miles), with steep, mountainous terrain, low-hanging cloud and thick bush. It's also home to the last outpost of trees (southern rātā) en route to Antarctica. The island's western cliffs are tall and foreboding, eaten away by ferocious seas driven by gale-force westerly winds, while its eastern side, with its many undulating coves and inlets, is more sheltered and slightly more welcoming for visitors.

One year later, Bristow returned and spent several weeks exploring the islands. He visited during the winter so he missed the sea lions lounging on the sandy beach at Enderby Island, but he would have seen the bellbirds and parakeets flitting through the tangled rata forests (Metrosideros umbellata), royal albatrosses soaring overhead, and white-capped and light-mantled sooty albatrosses nesting in the islands' rocky cliffs.

During his second visit, Bristow formally claimed the islands for Britain, naming Auckland Island's sheltered northern harbour 'Sarah's Bosom after his ship the Sarah (the name was later changed to Port Ross in honour of the British explorer James Clark Ross). Bristow also released a number of pigs on the main island to feed any future visitors — a generous but short-sighted act that is still causing headaches for the New Zealand Department of Conservation more than 200 years later (see Chapter 12).

Not much else is known about Captain Abraham Bristow, except that in 1809 his ship the Sarah was snatched by a French privateering ship called the Revenge, which in turn was taken by a British privateering ship called the Helena, and then all three ships were claimed by yet another French privateering ship, called the Enterprise. Life at sea was a complicated, risky affair in the early 19th century.4

For a long time the visiting sealers disregarded the Auckland Islands' new name and simply called the islands 'Bristow's Land'. As with Macquarie and Campbell islands, they plundered the coastlines and slaughtered the seals for their skins and oil until there were barely any left.

Benjamin and Abby Morrell: the love boat

Between 1820 and 1840 the Auckland Islands were visited by several renowned explorers, a few of whom provided glowing accounts of the mild weather, excellent harbour and fertile soil, declaring the uninhabited islands to be an ideal location for a prospective settlement. Their naively optimistic reports would have consequences for decades to come.

At the time it was becoming more common for sea captains to take their wives along on expeditions, partly for company (voyages often lasted for two to three years) and also to maintain a sense of decorum on board. There were mixed feelings about this encroachment into men-only territory, and the ships with captain's wives on board were often known as 'hen frigates'.5