Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Ratgeber

- Sprache: Englisch

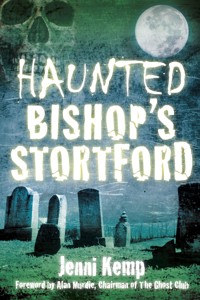

From a spectral horse and carriage heard galloping along Church Street to unexplained sightings of the market town's mysterious Grey Lady, this collection of hauntings from Bishop's Stortford is guaranteed to make your blood run cold. Featured here are reports of a shrieking woman in Water Lane, the ghost of a Victorian child at the Black Lion pub, an ominous black shape in the graveyard of St Michael's church, and even a phantom army from the days of Cromwell, among many others. So draw the curtains, dim the lights, choose your favourite chair and immerse yourself in a journey into the realms of the supernatural.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 124

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

MY thanks go to Sarah Bush, Ken Baker, Peter Barker, Pat Bricheno, David Brown, Marie Brown, Graham Burgess, the Butt family, Liz Eldred, Colette and Joe Entwisle, Kate Entwisle, Mike Hibbett, Lisa and Steve Hockley, Marc Hollingworth, Jack Kemp, Mr N. Maddams, Alan Murdie, Jeanne Powell, Su Purcell, Tracey Sneddon, Val White, Claudia Wiggins, Wally Wright, and Steve Wood.

I also thank the scores of other people working in public houses, restaurants, offices and shops who gave me information enabling me to write this book. The honest, reliable and frank reports were given to me by sincere, ordinary people who had experienced, or knew of, the ghostly occurrences recorded here. Some of those mentioned above are also thanked for their help on computer matters.

I would also like to thank Matilda Richards and Emily Locke of The History Press for their help and patience.

All photographs are from the author’s collection unless otherwise stated. Illustrations are by the author. (‘The Shrieking Woman’ illustration on page 55 is an idea taken from ‘Nemesis of Neglect’ by John Tenniel for Punch magazine, 1888.)

CONTENTS

Title

Acknowledgements

Foreword by Alan Murdie

A Brief History of Bishop’s Stortford

Introduction

What is a Ghost?

one

Windhill, High Street and the Police Station

two

North Street

three

Potter Street and Market Square

four

Bridge Street

five

Hockerill Crossroads

six

Other Streets and Thoroughfares

seven

Waytemore Castle

eight

The Thorley Area

nine

Close Environs and Villages

Glossary of Terms

Bibliography and Recommended Reading

About the Author

Copyright

FOREWORD

IN 1961 it was estimated there were some 10,000 reputedly haunted places in Great Britain, though further enquiries frequently revealed many of these to be regrettably inactive.

Some towns and cities, including York, Edinburgh, Cambridge, Farnborough and Cheltenham, seem to routinely generate many reports of ghosts and hauntings. Certain famous locations, such as the Tower of London, Hampton Court Palace, Glamis Castle in Scotland, Berry Pomeroy Castle in Devon and Newstead Abbey in Nottinghamshire have all appeared in ghostly guides and gazetteers many times since the Victorian era.

Yet reports of ghosts and haunting in the UK are by no means evenly distributed. Often stories seem to be concentrated in a relatively small pocket, whilst large swathes of the UK seem to be almost wholly bereft of ghost sightings. Curiously, although a town with a long history, Bishop’s Stortford appears to be one such location, omitted from all major ghost-hunting guidebooks and gazetteers covering Britain. Even in Hertfordshire folklore, the ghosts of Bishop’s Stortford seem to be conspicuously absent, and the most diligent searches of county libraries and newspapers have turned up but a small handful of reports at the beginning of the twenty-first century.

Some people have speculated about certain areas being ‘window areas’, more prone to being haunted than others. However, the relative absence of ghost stories in particular places may simply reflect the absence of anyone prepared to record such accounts.

That there were ghost stories awaiting discovery in Bishop’s Stortford I was long certain. As a child I had been told by a relative of his own experience of seeing the ghost of a woman in his house in the town, early one morning in 1948 or 1949. He was sure it was the ghost of the previous owner, who had committed suicide by gassing herself in the kitchen. This apparition only appeared once or twice, and was treated simply as a matter of fact, rather than as a cause for concern.

With Haunted Bishop’s Stortford Jenni Kemp has produced a most welcome book demonstrating that such local ghostly experiences are by no means unique. In collecting and publishing these accounts for the first time, she restores a long-overdue balance to the study of haunted places around Hertfordshire, showing that as a town Bishop’s Stortford merits a major entry on any map of haunted Britain. Her intriguing and fascinating book provides many new leads for ghost investigators and brings a whole new dimension to the town for visitors and tourists. I am sure it will also set many local readers searching through its contents, fearing the worst about some of the places they know and frequent.

Alan Murdie

Chairman, The Ghost Club

2015

A BRIEF HISTORY OF BISHOP’S STORTFORD

USUALLY a town is named after a river that runs through it or nearby, but in this case the River Stort was named after the town. Esterteford was a Saxon manor mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086. The name may derive from Steorta, a family that ruled here. In 1060 the manor was sold to the Bishop of London by Edith the Fair, mistress of King Harold, and became known as Bishop’s Esterteford – hence Bishop’s Stortford.

The manor was important to the Romans as it was on a route from St Albans to Colchester. Their encampment was in the town meads area. After the fall of the Roman Empire the town was deserted – then the Saxons came.

The Normans were responsible for building the castle known now as Waytemore Castle mound, as only the mound remains in Castle Gardens. In 1208 King John was in dispute with the Pope. He captured the castle from the bishop and had the castle destroyed. In 1214 he was ordered to have it rebuilt at his own cost.

Stortford succumbed to plague three times: the Bubonic Plague in 1349 (1346–1353), which wiped out half the town’s population, the Black Death in 1582/1583, which it took sixty lives, and the Great Plague of London in 1665, which spread through the Stort Valley and the town, wiping out half the population.

Maze Green Road was once named Pest House Lane. This probably originated from the pesthouse that was situated at the top of the road outside the town boundary. In medieval times every town had its mazel or leper house, and the green at the top of the road may have been the site of the mazel – hence Maze Green Road.

The sick of Bishop’s Stortford were not put in isolation until the pesthouse was built.

Bishop’s Stortford has been a market town since medieval times. The market and fairs were held outside the church and further up Windhill above flood level. By 1801 the town had flourished, and the corn exchange was established, the main business being malting. The river was used to convey malt supplies to London’s breweries. The river canal was later used to ferry timber, coal and other goods.

There was a weekly cattle market, which took place at Northgate End and was described in 1767 ‘as the finest in England’. The market was discontinued in the 1960s.

Not to Scale

During the Civil War the people of Stortford supported Cromwell’s men, except Lord Capel of Hadham Hall, a noted Royalist. Cromwell’s men were billeted at St Michael’s church and the Boar’s Head, opposite. Richard Whittington (Dick Whittington (1358–1423), Lord Mayor of London) was Lord of the Manor of Thorley. A school and road are named after him on the Thorley estate.

In the eighteenth century, Stortford was a thriving hub on the route from London to Cambridge. Four inns stood at the Hockerill crossroads. King Charles II, his mistress Nell Gwynne, Samuel Pepys the diarist, and the highwayman Dick Turpin all stayed at these hostelries. Now only one of these old inns survives – the Cock Inn, situated on the corner of Stansted Road and Dunmow Road. The George in North Street was a terminus for the stagecoach that ran daily to The Bull in Aldgate, London. Due to the flow of travellers more inns appeared. Although the birth of the railway saw the death of the stagecoach and the wane of such hostelries, some of these ancient inns are still standing and providing sustenance to the populace today.

The Victorian era saw a steep ascent in technology and enterprise. Bishop’s Stortford had a fire brigade in 1880, and a police station in 1890. Cedar Court in Rye Street, a large building converted into apartments, was originally the town’s first hospital. The hospital was built by the well-known Frere family of Twyford House on Pig Lane, on land donated by Sir Walter Gilbey, co-creator of the well-known drinks firm W.A. Gilbey – Gilbey’s Gin, who was born and lived at The Links on Windhill, previously a farmhouse.

The population of the town greatly increased during this era and further housing was built; Newtown Road, Jervis Road, Apton Road and some of the surrounding streets were the main areas developed.

In the early 1800s the Stortford workhouse was at Hockerill, which was sheathed by tall brick walls. A barn housed itinerants. The old workhouse was sold, together with the pesthouse in Maze Green Road, and the New Union workhouse was built in Haymeads Lane to house 220 of the town’s paupers, who worked at spinning and manufacturing sacking, twine and rope.

After the First World War the workhouse was converted to an emergency clinic, which became the Herts & Essex Hospital. Now the site houses the modern Community Hospital and the old workhouse buildings have been converted into housing, surrounded by newly built dwellings. The streets are aptly named: Cavell Drive (Nurse Edith Cavell), and Nightingales (Florence Nightingale).

Cecil Rhodes, the founder of Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe, was born and educated in Bishop’s Stortford. His former house is now the town’s museum, theatre and arts centre.

Bishop’s Stortford was the first town in Hertfordshire to raise a volunteer training corps in the First World War. The volunteers were made up of those too old or infirm to join the Forces. Men could enrol at the old post office – which was at the top of Devoils Lane where the Saffron Walden Building Society now sits at the top of the steps – or at a shop in North Street. Each member had to attend forty drills a year and earn a second class in musketry.

Oak Hall in Chantry Road was a prisoner-of-war camp.

St Michael’s church, Windhill. Historically markets and fairs were held outside the church.

Women worked on the land and as farmhands and dairymaids. They were also employed as nurses, and in factories and shops.

Bishop’s Stortford sustained few bombing raids during the Second World War compared with other towns. Bombing took place around Portland Road, Cricketfield Lane, Dunmow Road and the River Stort near Southmill Lock.

Post-Second World War the town’s population gradually increased and consequently new homes were erected at Thorley Park, St Michaels Mead, Bishop’s Park, Bishop’s Gate, the area around Parsonage Lane, the Warwick Road locality, Havers Lane region, and the old workhouse site. As a result, the shopping area gradually expanded to cope with the extra populace. Jackson Square Shopping Centre was erected in 1973 and then enlarged in 2007. Florence Walk and Sworder’s Yard are two small shopping malls, and a new complex down by the railway station has sprung up. There are talks of a new project near the centre of the town as well.

Most of the towns nearby are small and the surrounding Hertfordshire and Essex villages regard Stortford as a centre for trade and recreation.

Further historical notes can be found amongst the ghost stories in each chapter.

INTRODUCTION

THERE are two particular stories that are well known and celebrated in Bishop’s Stortford: that of the legendary tunnels, and the famous ghostly Grey Lady. Almost as soon as a stranger enters the town he or she is told of one if not both.

The Grey Lady has haunted Bishop’s Stortford for hundreds of years and she ‘pops up’ in shops, pubs, offices and even the police station. The main area of the haunting is an east/west line from Windhill to High Street, down Bridge Street, although her presence has also been felt in properties in North Street and Potter Street (north/south). Interestingly, these haunts follow the line of an underground tunnel which is purported to run from Windhill down to the River Stort. This is the oldest part of the town and the east/west and north/south pattern of the roads forms the shape of a crucifix or cross (see map on page 10).

The identity of the Grey Lady is unknown, but her spirit allegedly frequents the old monastery on Windhill, now occupied by commercial offices, the Boar’s Head Inn, the George Hotel, Prezzo restaurant, the Oxfam shop, the Black Lion public house, the Star Inn, Nockolds solicitors offices in Market Square, and the former premises of Tissiman’s Menswear (at present unoccupied) in the High Street. Her ghost has been described as both terrifying and vicious. I am sure that not all sightings of a Grey Lady or misty figure are one and the same ghost – she would have to be a very enthusiastic and industrious soul to patrol the number of haunts she is supposed to visit! It would seem that any haunting or supernatural occurrence in Bishop’s Stortford is put down to the Grey Lady when in fact the townsfolk may not realise that other spooks abound.

It is said that underneath Bishop’s Stortford’s roads and pavements lie a maze of ancient, dark tunnels. There are tunnels, but probably not as many as some would have us believe. There definitely is an underground passageway at the Charis Centre in Water Lane, another bricked up entrance to a tunnel at the Boar’s Head, a shaft which probably leads to a tunnel at Coopers Hardware Store, and underground cloisters at the NatWest Bank.

Tradition says that a tunnel runs from St Michael’s church across the road to the seventeenth-century Boar’s Head and connects up with the fifteenth-century George Hotel on the corner of North Street and High Street. It then runs down Bridge Street to the sixteenth-century pub The Star, and carries on to the Waytemore Castle mound across the river. This may be true, but some believe that the tunnels stop at the foot of Bridge Street, as it would be very difficult to excavate under the river. The geology of the land at this location would make it difficult to dig through gravel, sand and clay. It is not impossible, but it would have to be extremely deep. A former vicar of St Michael’s church – which dates back to 1400 in parts – indicated that he had heard of the tunnels but there is no evidence as far as the church is concerned – it does not even have a crypt.