Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Ratgeber

- Sprache: Englisch

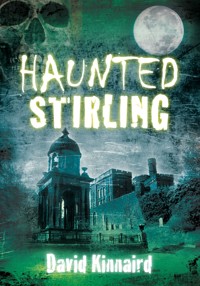

From heart-stopping accounts of apparitions, poltergeists and related supernatural phenomena, to first-hand encounters with phantoms and spirits, this collection of stories contains both new and well-known spooky tales from around Stirling. A whole chapter is dedicated to the mysterious goings-on at Stirling Castle, where cleaners in the King's Old Building claimed to have heard footsteps coming from the third floor — which hasn't existed since a fire in the nineteenth-century; while a 1930s photograph purports to capture the shadow of a phantom guardsman — possibly the same 'Highland Soldier' often reportedly mistaken by tourists for a castle guide. The town itself has no shortage of fascinating tales, including the story of the Old Town's most famous phantom, seventeenth-century merchant John 'Auld Staney Breeks' Cowane, whose spirit is said to inhabit his statue each Hogmanay. A playful ghost supposedly throws pots and pans around the kitchens of the Darnley Coffee House, while frequent power failures and mishaps in the Tolbooth Theatre — originally the eighteenth-century Burgh jail — are blamed upon the malicious spirit of the last man hanged, Alan Mair. Drawing on historical and contemporary sources, Haunted Stirling is guaranteed to intrigue and chill both believers and sceptics alike.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 170

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

HAUNTED

STIRLING

1

The Tollbooth

(see page 11)

2i

Mar’s Wark

(see page 25)

2ii

John Cowane’s Hospital (Guildhall)

(see page 30)

2iii

Cowane’s House

(see page 32)

2iv

Argyll’s Ludging

(see page 37)

3i

Holy Rude Graveyard

(see page 42)

3ii

Gowan Hill

(see page 58)

4

Stirling Castle

(see page 62)

5i

Darnley’s House

(see page 76)

5ii

Nicky-Tam’s Bar & Bothy

(see page 79)

5iii

The Settle Inn

(see page 83)

5iv

Les Cygnes Coffee House

(see page 87)

HAUNTED

STIRLING

David Kinnaird

For Eilidh Brown

(03.04.94 – 25.03.10)

First published 2010

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© David Kinnaird, 2010, 2013

The right of David Kinnaird to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 5644 4

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1.

The Tolbooth

2.

Famous Sons

3.

The Graveyards and Gowan Hill

4.

Stirling Castle

5.

Whines and Spirits

Afterword

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Elspeth King, Michael McGinnes and The Smith Art Gallery & Museum (www.smithartgallery.demon.co.uk); Tony Murray ([email protected]); The Heritage Events Company/The Stirling GhostWalk (www.stirlingghostwalk.com); Brian Allan(www.p-e-g.co.uk/www.brianjallan-home.co.uk); the staff of the Tolbooth Theatre(www.stirling.gov.uk/tolbooth); Derek Green of The Ghost Club of Great Britain(www.ghostclub.org.uk); Willie McEwan, Ross Blevins and all at Stirling Castle (www.stirlingcastle.gov.uk); and Joyce Steel and the Museum of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders (www.argylls.co.uk/museum.htm).

Introduction

Their Pomps and Triumphs stand them in no stead;

Their Arches, Tombes, Pyramides high

And statues are but vanitie

They die, and yet would live in what is dead.

William Alexander, Earl of Stirling (Epitaph, 1640)

Do you believe in ghosts? It’s a simple enough question, and one I’ve been asked many times over the past two decades as a performer and scriptwriter for the Stirling GhostWalk, a dramatic tour telling tales drawn from the rich heritage and folklore of the Royal Burgh, and performed before the glorious backdrop of the historic Old Town. Simple as it is, it’s not a question which avails itself of a simple answer.

What is a ghost? Why do those whose days are done, whose bones lie buried in the dark and dusty earth, torment themselves in nightly visitation of those who live and breathe? Some say that ghosts are nothing more than shadows, memories, or moments of pain or passion trapped in time like a fly in amber. Others believe that spirits lack the will or wit to know that their days are done, and endure a breathless imitation of their former daily drudge, or that they are unable – or unwilling – to traverse the Crow Road that links our world with whatever it is that lies beyond. What binds them here? Unfinished business? An unrequited longing for love, honour or revenge? All of the above – if half the tales told of Stirling’s Old Town have a word of truth to them.

My own interest in these stories has always lain in the quirks of their dramas, and their worth – whether they are true or false – in the cultural currency of the communities of the Castle Crag. Often the historical context of a tale, or the manner in which events manifest or are interpreted, can be as intriguing as the stories themselves. I’ve never seen a ghost. After two decades of living and working in a host of supposedly haunted houses, acquainting myself with the history and mythology of the area, I’ve yet to see, hear or feel anything that I could not explain – at least in part – by reasonable, rational, and utterly mundane means. I’m not even sure I believe in ghosts, at least not in the sense of a sentient, self-aware, persistent personal essence – but I’m open to the possibility. After all, if it is true that high emotions can somehow impress themselves upon a location, then it’s no surprise that reports of hauntings have been so numerous in this town. From the blood and thunder of Civil War and the medieval struggle for independence, to the schism and strife of the General Strike; from the intrigues and infamies of the Stuart Court to the boisterous bustle of many a long ago demolished Broad Street slum, Stirling’s turbulent, passionate past provides a rich resource of raw material – and a supporting cast which includes the likes of Wallace, Bruce, Burns and the ill-starred and ubiquitous Mary, Queen of Scots.

I have been fortunate that my work as a writer and actor has availed me regular access to the sites mentioned in the following pages, and has allowed me to participate – either as a performer or historical advisor (though I make claim only to being an enthusiast, not an expert) – in many studies of supposed hauntings in the town. I am grateful, too, that my status as a ‘weel ken’t face’, if only in the ghoulish guise of Stirling’s last hangman, Jock Rankine (of whom you will read more very shortly), has opened doors for me, helping persuade local people and genuine experts in the history of the area – Tony Murray and Elspeth King deserve particular mention – who have helped me root out the putative ‘truth’ behind some of the town’s strangest tales. The Ghost Club’s Derek Green and Brian Allan, of Strange Phenomena Investigations – both seasoned investigators with experience of a number of reputedly haunted sites in the town – have also been invaluable in their support.

This author, in my GhostWalk guise of Jock Rankine, the Stirling Staffman. (Image courtesy of Heritage Events Company)

Some of the stories which follow were well known to me – the Green, Black and Pink Ladies, and the murderous Alan Mair, have all frequently featured in GhostWalks over the years. Some tales, like those of Blind Alick Lyon, the ‘Mar Changeling’ and the ‘White Lady of Rownam Avenue’, are almost certainly apocryphal, but the manner of their creation speaks volumes about the nature (and endurance) of local myth. Others still – the strange twentieth-century tale of the ‘Millhall Ghost’, for example – were entirely new to me, and accounts of unexplained encounters in modern pubs and coffee houses bring us from the gothic gloom of the Old Town into the busy bustle of the contemporary city. I don’t have an axe to grind, or anything to prove, and you’ll see the sentiments of both the sceptic and the sensitive in coming chapters. As Hamlet said, ‘There are more things in heaven and earth … than are dreamt of in your philosophy’ – and, as an old schoolteacher of mine sagely warned, it is never a good idea to argue with a Great Dane.

I have focussed solely upon the stories of the Old Town and Castle Rock; Bannockburn and Breadalbane tales of the mystical Hand of St Fillan, Aberfoyle’s ‘Fairy Minister’ Robert Kirk, and modern marvels such as the ‘Cowie Poltergeist’ will have to wait for another day. All of the sites mentioned, incidentally, are within easy walking distance of the modern town centre, and I hope that this guide will be of as much interest to heritage hounds as horror buffs. Readers with an interest in the history of the witchcraft and faery lore of the area can do no better than refer to Geoff Holder’s excellent The Guide to Mysterious Stirlingshire. Those with more general tastes should seek out Craig Mair’s Stirling: The Royal Burgh. Stirling’s Smith Art Gallery & Museum on Dumbarton Road – just a few minutes’ walk from the main Tourist Information Centre – is a wonderful place to acquaint yourself with some of the city’s treasures first-hand.

Before we continue, a few words about Stirling itself. The etymology of the name – Sruighlea or Stirlin – is uncertain, but some suggest that it originates from an Old Scots or Gaelic term meaning ‘place of battle’ or ‘place of strife’, which would be fitting. A she-wolf rests, recumbent on our coat of arms, commemorating the fabled beast whose howls alerted seventh-century Northumbrian guards, then settled in their fortress of Urbs Giudi on the Castle Crag, to Viking invasion in dead of night. Some might say we have been howling at the moon, from that stern vantage point, ever since. It was one of the principal strongholds of Scottish monarchy from the time of David I, who granted Stirling status as a Royal Burgh in 1130, and was a favourite seat of the Royal House of Stuart – who took their name from Walter Stewart, Keeper of the Castle, High Steward of Scotland, husband to Marjorie Bruce (daughter of Robert I) and father to the first of that kingly line, Robert II. Next to the coursing flood of the River Forth, near the boundary between the Scottish Lowlands and Highlands, it was the ‘Key to Scotland’ – strategically important in every invasion and armed conflict to afflict the nation from the Roman stramash with Calgacus at Mons Graupius to the Jacobite Rising of 1745. Falling from courtly favour after the 1603 Union of Crowns, it became a hub of Caledonian commerce and light industry, with a busy port. It boasts a university, opened in 1967, and a population of around 45,000. Smaller than many of the country’s larger towns, it became Scotland’s newest city in 2002, as part of Queen Elizabeth II’s Golden Jubilee celebrations.

A she-wolf watches protectively over the entrance to Stirling’s Tolbooth. (David Kinnaird)

The dance of death – the seventeenth-century Sconce Lair. (David Kinnaird)

On the subject of monarchs, where rulers have titles in Scotland and England – the norm after the Union of Crowns – Scotland gets ‘top-billing’ (this is a book about the ‘Key to the Kingdon’ after all). James the Sixth of Scotland and First of England will be rendered ‘James VI (I)’, and so forth.

David Kinnaird, 2010

one

THE TOLBOOTH

‘Him That’s Born Tae Be Hanged’ll Ne’er Be Drowned’ (Trad.)

The four faces of the Tolbooth’s pavilioned Dutch clock-tower stand stern vigil over the Old Town and environs, dominating the Broad Street skyline just as the building itself once proudly presided over the judicial and commercial life of the Burgh. Where better than here to begin our tour of the town? Erected between 1703 and 1705 to the design of Sir William Bruce of Kinross, the ‘Christopher Wren of North Britain’ responsible for the remodelling of Edinburgh’s Palace of Holyroodhouse, this stately structure’s foundations date back to (at least) the twelfth century. Fines and taxes were paid here, and from the fifteenth century a council chamber and courtroom were added. In 1785 Gideon Gray extended the property. Gray also designed the Golden Lion Hotel in Stirling’s King Street, then drolly designated as ‘Quality Street’ on account of the reprobates and roister-doisters residing within its drear tenements, taverns and coffee houses. One visiting villain, the ‘ploughman poet’, Robert Burns, was obliged to smash the hotel window upon which he had scratched his controversial ‘Lines on Stirling’ (seeChapter 4). Rabbie was fortunate that neither the sedition of his sentiment nor the vandalism which erased it from scrutiny was the cause of his own visit to the Tolbooth that same year. Though the ‘ploughman poet’ may have been discommoded by the Burgh’s loutish local literati, he would have had much greater cause for complaint had he been forced to spend even a short time in what would soon be dolefully dubbed ‘the worst jail in Britain’. Richard Crichton further extended the jail and courthouse in 1806.

Currently a theatre and arts centre, this imposing edifice has a suitably patchwork past, serving as a workhouse, and – in more recent memory – a restaurant, an artists’ studio, a wartime army recruitment post, tourism development offices, and dressing rooms for public performances staged as part of the popular Royal Burgh of Stirling ‘Living History’ programmes of the early 1990s. It was in this last capacity that I first came to know (and explore) this fascinating building. My former dressing room, the Judges’ Robing Room, is now the theatre bar.

For all its kudos as a contemporary cultural hub, the Tolbooth’s history is as grim as its great grey walls. Geoff Holder gives extensive account, in The Guide to Mysterious Stirlingshire, of the many unfortunate biddies bound over, tortured and tried for witchcraft in earlier buildings to occupy this site, and a wall-plaque in Broad Street – formerly Market Street – commemorates the ritualised butchery, on 8 September 1820, of the weavers John Baird and Andrew Hardie. Commanders in the Radical War of 1820, Baird and Hardie were hanged and decapitated for High Treason after leading a protest march to the nearby Carron Ironworks ‘FOR THE CAUSE’, their plaque proclaims, ‘OF JUSTICE AND TRUTH’. Dangerous men, indeed. It was not, after all, for the commoner to challenge his lot in life: a man – if his surviving letters, currently in the care of Stirling’s Burgh Archive, are any indication – of passionate spirit and intelligence, Hardie’s accusers saw in him as no ‘martyr to the cause of truth and justice’, as he described himself upon the scaffold, but merely one (according to a contemporary account of his unfortunate end) who was ‘bred a weaver’. These dark deeds have all played their part in shaping the building’s legacy. The Tolbooth, you see, has a reputation.

A plaque on the Tolbooth’s Broad Street wall commemorates the hanging and beheading of John Baird and Andrew Hardie (‘FOR THE CAUSE OF JUSTICE AND TRUTH’) in 1820. (David Kinnaird)

The Executioner’s cloak and axe, last used in the execution of Baird and Hardie. (Picture reproduced by kind permission of the Smith Art Gallery & Museum)

The Staffman

Thieves in the Burgh might find their hands pinned to the prison door on market day; perjurers their ears. Victims would be left to slowly and painfully pull their tattered, bloody flesh free, and those tempted to assist a friend in extricating themselves from such sorry situations might find their helping hands (or ears) hastily hammered by the town torturer, the Staffman (a title unique to Stirling).

The last to occupy that onerous office was an unpleasant Ayrshireman named Jock Rankine, whose spirit – one of the Burgh’s most enduring bogeymen – could once be heard each night in the alleyway adjoining the old prison. The tell-tale tap-tap-tapping of his ceremonial staff and his gasping, guttural growl echoed through the high-walled huddle of this mean vennel, the appropriately named Hangman’s Close. The location of his official residence – ‘a mere apology for a human habitation’, according to William Drysdale’s Old Faces, Old Places and Old Stories of Stirling – was a two-storey building with a crow-stepped gable to the street. The ground floor served as a stable, the first-floor residence was entered by an outside stair. A dingy close passed under the Staffman’s house, connecting St John Street with Broad Street.

Torn down during extensive urban renewal programmes, which cleared away centuries of densely-packed lodgings and alleyways, Hangman’s Close was supplanted by more modern (if considerably less durable) crow-stepped council housing in the 1950s. Many a local lad was warned to keep away from the wasted wynd when darkness fell, for fear that the Staffman would get them. To venture into its night-shrouded shadows was a test of many a Broad Street brat’s mettle. This is oddly fitting, as in life Rankine’s grumbling glower was infamous, making him a prime target for the constant taunts and tricks of the local ‘kail runts’.

The Staffman’s house around 1860. (Image based on an original illustration by J.S. Fleming)

One of the perquisites of his post was the right to freely fill his Staffman’s caup (cup), or ‘Haddis-Cog’ – the only part of the Staffman’s official regalia to survive (displayed in the Smith Art Gallery & Museum) – from any merchant at the weekly Meal and Butter Markets, and fill his wooden Quaich at any tavern: privileges he greedily exercised at every opportunity. He served, too, as a sometime debt collector – on behalf of the minister of the parish. Jock’s lack of good grace might have been better borne by the Burgh had he been more competent in the exercise of his duties. Drysdale recounts his less than sterling performance during the despatch of a young woman, condemned for throwing her illegitimate child from the Old Bridge into the River Forth. The execution involved the traditional Scots gib, a wooden beam fixed in a large stone, with a crossbar at its top, and a number of hooks fixed thereon. The condemned was made to ascend one ladder and the Staffman the other. After hooking and tying the noose, the executioner simply pushed the ladder away from the beam, and removed his own. Slow and painful strangulation followed. In this case, however, all did not go according to plan. The victim …

The Staffman’s caup – the only item of the town torturer’s regalia to survive. (Picture reproduced by kind permission of the Smith Art Gallery & Museum)

… had got hold of the ladder, and Jock was quite unable to perform his duty. Attending the sad scene were the town officers with their halberts, and one of them, Tom Bone, seeing the dilemma, went deliberately up, and gave the woman’s fingers several knocks with his halbert, which caused her to let go, and Rankin succeeded in pushing her off. A good deal of sympathy was expressed for the woman, but Bone’s vulgar and inhuman interference incurred the dire displeasure of the juvenile and female portion of the community, and he had to be escorted to a place of safety until the affair blew over.

For all the guard’s cruelty, it was Jock’s callous incompetence that was remembered. Legend has it that the ‘last limb of the law’ choked to death on a chicken bone strategically slipped into his soup by his surly spouse, a prostitute and sometime laundry thief named Isabella Kilconquahar, known to neighbours (on account of her impenetrable Irish brogue) as Tibbie Cawker. Under sentence in the dismal dungeon of the Tolbooth, Tibbie was offered immediate release – on condition that she married the Staffman and kept his house. She had cause to regret her choice of ‘freedom’. Beaten and bullied by her new husband, no-one in the town batted an eye when she finally despatched the old gowk.

The Mercat Cross – viewed from the former entrance to Hangman’s Close. Hangings occurred here between 1811 and 1843. (David Kinnaird)

His spectre’s gagging growl is explained as his eternal effort to dislodge the fatal fowl-bone from his gullet. Too much dramatic irony to be true? Quite. This part of Jock’s myth is pure invention – possibly created by parents eager to discourage their offspring, the descendants of the same errant quots who had plagued him in life, from playing in the derelict close – a night shelter for vagrants by the late nineteenth century. Stirling Town Council minutes for 2 February 1771 provide him with a more plausible (if less satisfying) end, revealing that the troublesome torturer was simply sacked for causing ‘great annoyance and disturbance to the neighbourhood’ and keeping a ‘bad house’, and provided with ten shillings sterling to get out of town. He died in Ayr around 1794. Current residents of the council houses built on the site report no continuance of the phantom Staffman’s percussive presence, though he is still seen from time to time – as my own frequently favoured alter ego on the Stirling GhostWalk.

The Body in the Box