Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

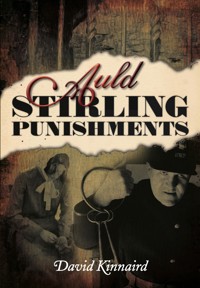

From the murder of James I and the brutal torture of his betrayers to the beheading of Radical Weavers Baird and Hardie, the history of crime and punishment in Stirling's Royal Burgh has reflected the passions and prejudices of the Scottish nation. Here are shocking tales of the brutal and the bloody, the sad and the seditious, of the thieves, traitors, murderers and martyrs who shaped the destiny of those who dwell upon the Castle Rock. Richly illustrated, and filled with victims and villains, nobles, executioners and torturers, this book explores Stirling's criminal heritage and the many grim and ancient punishments exacted inside the region's churches, workhouses and schools. It is a shocking survey of our nation's penal history.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 196

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Auld

STIRLING

PUNISHMENTS

Auld

STIRLING

PUNISHMENTS

David Kinnaird

For Patricia Brannigan: having worked on the Stirling Ghost Walks with me for ten years, she knows what punishment is all about.

First published 2011

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© David Kinnaird, 2011, 2013

The right of David Kinnaird to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUBISBN 978 0 7509 5350 4

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1 Early Places of Punishment

2 The Burgh

3 Beggars,Tramps and Thieves

4 ‘Against God and the King’

5 A New County Jail

Afterword

Bibliography

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author would like to thank Tony Murray, Dr Elspeth King and her staff at the Smith Art Gallery and Museum, Stirling District Tourism and the staff of the old Town Jail, Alistair Campbell and the staff of the Tolbooth Theatre, Julia Sandford-Cooke, Patsy James of the Heritage Events Company, Rochelle MacDonald, Allan Goldie and Patricia Brannigan for their assistance and support during the writing of this text.

INTRODUCTION

Frae a’ the bridewell cages an’ blackholes, And officers canes wi’ halberd poles, And frae the nine tail’d cat that opposes our souls, Gude Lord deliver us.

(Traditional Scots grace)

Just before Christmas 2010, as I started preparing what I hoped would be the final draft of the book now in your hands, I was burgled. As if being robbed when one is in the process of producing a book on local crime and punishment wasn’t replete with sufficient irony, I was –as my front door was splintered open, my lock shattered, and my sense of wellbeing sorely shaken –sitting, seasonally attired, in Santa’s Grotto, telling tots tall tales of how a certain jolly, red-faced chap would soon be creeping into their homes and leaving little surprises for them. Ho, ho, ho! I was assuredly livid of cheek, but rather less than jolly, to discover that my PC and laptop had been trashed –and several months work lost.

This prompted two responses. The first was a sudden compulsion to cast off my long-cultivated Guardian-reading liberal sensibilities and fulminate furiously on plans for visiting upon my transgressors the self-same visceral punishments I’d been studying for so long. Secondly, with a deadline looming, was the more pressing concern of selectively reconstituting the salient points of what had been lost. Both reactions, the first borne of indignant ire, the latter of gut-wrenching panic, proved oddly productive. My anger –my righteous rage that the order of my home and my life had been set awry by an aberrant, anti-social invader who should (no, who must) be punished in order to set right the troubled microcosm of my world –provided me, I think, with a valuable insight into how the punishments instituted by our forefathers to protect their homes, their lives and their communities arose as safeguards against the chaos of the world at large. My panic, similarly, helped me focus my gaze on those areas of history, and those particular punishments which inform us best about the mores and motives of those self-same citizens of Old Stirling. The Medieval era might well reveal a few gruesome, garish oddities, but the period between 1600 and 1900 saw the shaping of Stirling as we know it today –geographically and ideologically –and it was upon that era that I chose to linger longest.

As an actor and scriptwriter, I seem to have spent much of my professional life visiting Stirling’s punitive past upon the heads of unsuspecting audiences. As a performer on the Stirling GhostWalk –my original dressing-room was the judge’s robing room in the Tolbooth (the Burgh’s preferred spelling) Jail –I helped to recreate several early sixteenth-century trials in the (late eighteenth-century) courtroom, and used the condemned cell (without ever knowing it was such) as a makeshift office for short-order script revisions. I’m still known chiefly in the town as a latter-day incarnation of the town’s infamous last hangman, Jock Rankin, on the GhostWalks and within the Old Town Jail visitor attraction. I say ‘last hangman’, but…well, that point of local lore, like so many I was to touch upon while re-writing my manuscript, was a gobbet of received wisdom I’d find challenged by that pesky thing known as ‘the facts’. As I discovered from my reaction to home-invasion, it’s good to have one’s preconceptions challenged –and I hope that you find the punitive parochial peculiarities of the Royal Burgh on the following pages as entertaining and informative as I did writing (and re-writing) them.

Crime and punishment: criminals tried at the Tolbooth would usually find justice served at the Mercat Cross in Market Street, now Broad Street. (Photo by David Kinnaird)

Incidentally, financial references until around 1700 are to Pounds Scots rather than Pounds Sterling (roughly a sixth of the value). References to monarchs following the 1606 Union of Crowns note the Scots and English ranking –James the Sixth of Scotland and First of England being, accordingly, James VII

Before we continue, a few words about Stirling –the ‘place of strife’, as the odd Scots/Gaelic etymology of the name (variously Sruighlea, Strivelin or Stirlin) suggests. A she-wolf rests, recumbent on the coat of arms decorating the entrance to the courtroom of the Tolbooth, celebrating the feared and fabled beast whose baleful howls alerted seventh-century Northumbrian settlers upon the Castle Crag to Viking onslaught in the dead of night. It was one of the principal strongholds of Scots monarchy from the time of David I, who granted Stirling its celebrated status as a Royal Burgh in 1130, and it remained a favoured seat of the Royal House of Stuart –who took their name from Walter Stewart, High Steward of Scotland, husband to Robert Bruce’s daughter, Margaret, and father to the first of that famous line, Robert II. Next to the coursing flood of the River Forth, the walled community of the Castle Rock was the ‘Key to Scotland’, dividing Highland from Lowland –the stronghold of all who would hold fast to the nation since Agricola clashed with Calgacus at Mons Graupius. Falling from courtly favour after the 1603 Union of Crowns, it remained a hub of Caledonian commerce and light industry, with a busy port. It boasts a university, opened in 1967, and a population of around 45,000. Smaller than many of the country’s larger towns, it became Scotland’s newest city in 2002, as part of Queen Elizabeth II’s Golden Jubilee celebrations.

David Kinnaird, 2011

1

EARLY PLACES OF PLTFISHIIETFT

The Heading Hill

Occupying a small plateau to the north-east of Stirling Castle, a lesser mound of the greater Gowanhill, lies Mote Hill – known more commonly to Stirling residents as ‘The Heading Hill’. Easily accessible from the sweep of the Back Walk, the line of the defensive Medieval Burgh Wall, it is thought to contain the vestigial remnants of a Pictish hill fort, though the last visible relics of that ancient structure, a low wall described by surveyors in 1794 (at which time it was known as ‘Murdoch’s Hill’), have long since vanished – probably plundered, like so many local ruins, for building materials. If it was a fort or settlement, serving the needs of an early community on the Castle Rock, then the name is fitting, such places (mons placeti, or statute hills) being used for moots – public gatherings, proclamations and punishments.

The hill, today, is dominated by two captured Napoleonic cannon, pointing out over the Stirling Bridge and Abbey Craig – sites significant in William Wallace’s victory over the occupying English Army, on 11 September 1297 – and by the conical iron covering of the ancient Beheading Stone.

The origins of the stone are unknown, though its close proximity to the castle and its visibility from the town seems to confirm the site’s appropriateness for courtly punishment: elevated and apart from the town, but, like the fortress in whose shadow it rests, commanding the attention of all. Beheading was reserved for those guilty of High Treason (the attendant punishments of ‘drawing’ and ‘quartering’ being only selectively enacted in Scottish ritual), and applied, therefore, to principally aristocratic felons, such as Murdoch Stewart, Duke of Albany. Grandson of Robert II, Stewart had ruled as Governor of Scotland during the eighteen-year English imprisonment of James I, insinuating his kin into positions of power and authority. When James’ £40,000 ransom was finally paid he returned to his homeland, launching pre-emptive attacks on those noble families whom he felt to pose a threat to his newfound authority. Foremost amongst these were the Albany Stewarts. Condemned for his mismanagement of the kingdom, the former Governor was beheaded along with his sons Walter and Alisdair, and his father-in-law, Donnchadh of Lennox, effectively hobbling the ambitions of the dynasty. His only surviving heir, ‘James the Fat’, fled to Antrim, Ireland, where he died in 1429.

The Beheading Stone: Mote Hill, a place of punishment since the Iron Age, sits in the shadow of Stirling Castle. (Photo by David Kinnaird)

An unpopular King, having diverted funds raised for the liberation of other ransomed Scots nobles into self-aggrandizing constructions, such as his new palace at Linlithgow, he quickly detained or executed many other rivals, amongst them Alexander, Lord of the Isles, Archibald Douglas and George, Earl of March. James was eventually murdered at Perth, on 20 February 1437, during an unsuccessful coup by another cousin, Walter Stewart, Earl of Atholl. No doubt inspired by his bloody example, James’ English bride, Queen Joan Beaufort, ordered the execution of the instrument of Walter’s ambition, Robert Graham, later that same year. After a three-day public exhibition of scourging, branding – a heated coronet searing the words ‘King of Traytors’ upon his brow – crucifixion, gradual dismemberment (his hands and feet cut off and cauterized) and partial strangulation, he was beheaded. He is recalled in the old verse:

Robert Graham Who slew our King, God give him shame.

Lesser punishments almost certainly occurred upon Mote Hill, though records of these do not survive. Justice would increasingly be enforced in other public places, quickly establishing themselves within the Burgh: at the Tron or Mercat Cross, with the construction of the new Tolbooth at the end of the fifteenth-century, entrenching a new oligarchical form of burgh government; and at the Barras Yett.

The Beheading Stone was not employed during the most infamous executions for treason in Stirling’s history, those of the Radical Weavers John Baird and Andrew Hardie, in 1822. Long thought lost, it was rediscovered sunken into the sod near the Old Stirling Bridge in 1887, where it had been used by several generations of local butchers for de-horning sheep carcasses. Rescued by the Stirling Natural History and Archaeology Society, it was restored to its original home upon the Mote Hill the following year.

The Burgh Wall

The line of the Back Walk, a scenic pathway completed to a plan by William Edmonston of Cambus Wallace in 1791, has provided visitors to the Burgh with panoramic views of the Old Town and surrounding countryside for generations – quickly proving itself to be one of the area’s first tourist attractions. Towering ominously over this pretty pathway stand the finest surviving remains of a medieval town wall in Scotland, whose line it follows from Dumbarton Road, in the heart of the contemporary city, to the castle itself. The wall, completed in 1547 with monies raised by the Burgesses and nobility of the Burgh, including Mary de Guise, mother of the infant Mary, Queen of Scots, and widow of James V, who ordered its construction, ‘to expend upoun the strengthing and bigging of the walls of the toune at this present peralus tyme of neid, for resisting our auld innimeis of Ingland’ – protected both town and Crown from the ambitions of England’s King Henry VIII, who sought to remove the young Queen from Stirling Castle, and, through betrothal to his own sickly heir, Edward (later, Edward VI), force a union of the two nations. The new defences were erected just in time to protect the communities of the Castle Rock from the worst devastations of what Sir Walter Scott would later term the ‘Rough Wooing’. English forces reached the town only a few weeks after completion, in September 1547.

The Burgh Wall: the sixteenth-century defensive wall raised by Mary de Guise to fend off the English, during the ‘Rough Wooing’, shaped Stirling’s destiny for centuries to come. (Photo by David Kinnaird)

To the north marshland made the town virtually unassailable. The Town Wall, therefore, was no mere defensive barrier, it was the key to understanding how Stirling worked as a unique social and political organism, and how it related to the outside world – particularly where issues of crime, punishment and the administration of justice are concerned – for the next three centuries.

The Gallows Mauling

There was, almost certainly, a much earlier wall: albeit a simple elevated earth rampart or wooden palisade. Records for 1522 mention the ‘Barras Yett’ – or Burgh Gate – and a ‘burrows port’ is referred to as early as 1477, though chroniclers carelessly neglect to state what the gate in question was attached to. There were, of course, several lesser gates – the Brig Port, near Stirling Bridge and the New Port, from which modern Port Street takes its name – but the broader Barras Yett strictly controlled access and egress to and from the town. It was the portal through which vagrants and vagabonds would be forbidden access, and from which those who had earned the enmity of the Burgh Court would be forever banished. Within sight of the gate – recalled by a simple pavement plaque at the modern intersection of Dumbarton Road and Port Street – stands the Victorian Black Boy fountain, dedicated to the staggering 30 per cent of Stirling’s population who perished from the plague during its ‘visitation’ of 1369. Despite its grim associations, this monument is a long-established place of public celebration. Locals gathered beneath it on VJ-Day, on 14 August 1945, when the Stirling Journal reported that ‘The Black Boy fountain was brilliantly lighted…Gaily coloured lights hung from the trees and the sight was one resembling fairyland.’ Clamorous gatherings on this spot had long been common, of course – but beneath a rather less festive bough. This was the original site of the Gallows Mauling (or Mailing) – the location of the public gibbet, or ‘gallows tree’, described by Victorian historian William Drysdale in Old Faces, Old Places and Old Stories of Stirling (1899) as:

The Barras Yett: The site of this ancient portal to the Royal Burgh can be still be found in the heart of the modern city, at the intersection of Port Street. and Dumbarton Road. (Photo by David Kinnaird)

The Gallows Mauling: the Black Boy fountain, a pretty Victorian monument to fourteenth-century plague victims, marks the site where the town gallows was once erected. (Photo by David Kinnaird)

A wooden beam fixed in a large stone, with a crossbar at its top, and a number of hooks fixed thereon. The unfortunates had to ascend one ladder, and the hangman another, and, after adjusting the rope, he pushed the culprits off to their fate, and then removed his ladder.

Executions occurred here until at least 16 May 1788, when forger John Smart was marched from the Tolbooth jail, through the Hangman’s Entry, along the line of the Town Wall and through the archway of the Barras Yett – symbolically expelled from the body and life of the town before he met his dismal end on the public gib. Future executions would occur in Market Street (now Broad Street), in the heart of the Old Town, by which time the ancient defences were finally being dismantled, allowing expansion over and beyond the old Burgh boundaries.

The Thieves’ Hole

A more palpable (and accessible) reminder of past punishment within the walled Burgh is to be found beneath the Port Street entrance to the modern Thistles shopping centre. A winding spiral staircase leads visitors into The Bastion, a sixteenth-century guard-room, complete with Thieves’ Pot, a subterranean bottle-dungeon into which nocturnal drunkards and mischief makers might be thrown by the Town Guard and detained overnight until they could be transferred to the cells of the Tolbooth. Believed to be part of Mary de Guise’s 1547 fortification of the Town Wall, and similar to the somewhat larger defensive tower of the Gunpowder Battery still visible on the ruined Town Wall, it may actually pre-date that structure, and was still in use at the end of the seventeenth-century, when Treasurer’s records note the sum of two shillings paid ‘for oyle to the irones in the thieves holl quen the Liddells [a family of notorious roister-doisters] wes put there.’ Decals and dioramas explain the part the structure played in the exercise of local justice and defence, displayed alongside the regalia of the Town Officers and the pug-faced figure of Justice which once adorned the entrance to the medieval Tolbooth, which preceded the current building. As we will see in subsequent chapters, in consideration of the Tron, Mercat Cross and other places of common punishment within the developing Royal Burgh between 1600 and 1850, Stirling’s punitive past is rarely far from the surface of the modern town.

The Last Bastion: beneath the modern Thistles shopping centre lie the restored remains of a sixteenth-century defensive tower and lock-up. (Photo by David Kinnaird, courtesy of the Thistles shopping centre)

The Thieve’s Pot: The Bastion served as a holding-cell for troublemakers within the town, and as a defence against attack from outside. (Illustration by David Kinnaird)

2

THE BURGH

The Tolbooth

Just as the castle dominates the Stirling skyline, a constant reminder of the power and majesty of the Stuart kings who called it home, the pavilioned Dutch clock-tower of the Tolbooth looms imposingly over the homes and businesses of the Old Town, in stern remembrance of the more immediate authority that buildings on this spot have exorcised over the local population for half a millennium. From the earliest days of the Royal Burgh the administration of local affairs was centred here. The first such building to occupy the current site in Broad Street was a largely wooden construction, erected in 1472. A rather more substantial stone structure appeared in 1575-76. Consisting of a courtroom and cells, a council chamber, an office where local tolls and taxes could be paid, a steeple and vaults, virtually nothing remains of either of these early edifices, though a ‘hol beneth the steeple’ still used as a storeroom, and recorded as having being in use immediately prior to an even more extensive rebuilding between 1703 and 1705 – to designs drawn up by Sir William Bruce of Kinross, described by Defoe as the ‘Christopher Wren of North Britain’ – may be the last remnant of these original structures. In 1785 Gideon Gray, also responsible for the local Grammar School (now the Portcullis Hotel) and Wingate’s Inn (currently the Golden Lion Hotel), seamlessly extended Bruce’s Broad Street frontage – his work described in Burgh records as ‘an extension of the Town House, prison and Clerk’s Office’. A final stage of development – at a cost of £1,583 10S 8d – followed between 1808 and 1810, with the addition of a new courtroom, cells and the prison block looking onto St John Street – designed by Edinburgh architect Richard Creighton. One significant feature of Creighton’s courtroom was the provision of public seating; most courts having previously met in private within various small rooms within the Town House, and public participation in proceedings actively discouraged.

Its functions gradually superseded by the construction of the current Municipal Buildings, Sheriff Court and Old Town Jail, the Tolbooth manages, still, to remain at the heart of local life, having seen service as a workhouse, an army recruiting post, a restaurant, tourist development offices and, most recently, a theatre and arts centre. Many of the features of Bruce, Gray and Creighton’s structures were restored between 2000 and 2001, during renovations by conservation architects Simpson and Brown.

The Tolbooth:William Bruce’s majestic eighteenth-century clock-tower dominates the modern Old Town, as other buildings on this site have for almost a millennium. (Photo by David Kinnaird)

A grim memento: one of the cell doors from Gideon Gray’s 1785 cell-block adorns a stairwell wall in the modern theatre.

The Tolbooth was not a prison as we would understand the term today. It was the dedicated seat of burgh government: a combined office of public record, civil administration and justice. Cells were required under renewed terms which confirmed the self-governing powers of the Royal Burghs, in 1469, but prisoners were rarely sentenced to set periods of penal servitude within its walls. Until the late eighteenth-century, custodial sentences, save for those assigned to the hard labour of the Workhouse, or House of Correction, were virtually unheard of – as was the notion that incarceration might in some way reform the characters of criminals. Jails were essentially little more than holding areas for those pending trial or, if already sentenced, awaiting the ‘pleasure of the court’ – whether that be the payment of fines, whipping, branding, banishment or execution. Given the transient nature of prison populations, there was seen as being little point in maintaining the cells in good order. As the Victorian era of improvement and innovation began to dawn, the Tolbooth continued as it had for two centuries or more: even the most modern parts of the building showing no reflection of changing ideas of prison construction The problems were fundamental, as one Circuit Court Judge, cited in John G. Harrison’s paper ‘The Stirling Tollbooth: The Building and its People, 1472-1847’ (1989), observed:

In the prison of Stirling there is, and can be, no classification of prisoners…In this prison the tried and the untried must necessarily be huddled together. The poor girl taken up for the first time, probably for some paltry offence, or for concealment of pregnancy, is placed in the company of hardened criminals, the thief by habit of repute. What can be the result of such things but contamination to the mind, ruin to the character in this world, and, it may be, perdition in the world to come?