16,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: ibidem

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Soviet and Post-Soviet Politics and Society

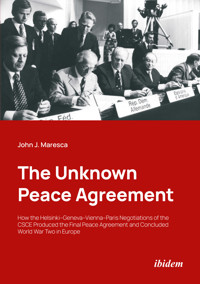

- Sprache: Englisch

The Helsinki Final Act of the 1975 Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE) set the rules for legitimate changes in national frontiers: They must be accomplished by peaceful means and agreement. Together with the Charter of Paris for a New Europe of 1990, the Helsinki Accords paved the way for a peaceful coexistence of the West and the Eastern Bloc. The Paris conference ended the Cold War, issuing a “Joint Declaration of Twenty-two States,” in which all member states of NATO and the Warsaw Pact affirmed they are no longer enemies. The Helsinki process, continuing in the form of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), resulted ultimately in the prevailing of pluralist democracy, market economy, and personal freedom. Today, it may serve as an example for how to deal with the current situation in Ukraine and crises in other regions of the former Soviet Union. John J. Maresca was a senior U.S. diplomat at the center of this long negotiating process. He was sent as the first, and only, US Ambassador to the newly-independent states after the break-up of the USSR-the American Ambassador to the “Near Abroad”-and started a negotiating process to try to end the one conflict in the region at that time. With this book, he presents his personal memoirs of how it was possible to reach the Helsinki Accords and following agreements?a story of astonishing change and evolution which is as eminently relevant today as it was 40 years ago.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 485

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

ibidemPress, Stuttgart

For my two only loves and my blessings—my wife Sisi, to whom I am indebtedfor herunderstanding and support,

Table of Contents

Foreword

John Maresca was certainly one of the people who was most closely involved in the early development of the CSCE, from the preparations at NATO, to its early years in Helsinki and Geneva, to the key Summit meeting in Helsinki in 1975, when the historic “Final Act” was signed.He is one of the few Americans who focused on the development of the CSCE during that period.As the central US official developing the CSCE in Washington he also helped to shape policies for the follow-up to the Helsinki Conference, and his 1985 book on the Helsinki negotiations remains a unique record of those landmark events.

Later Maresca also played a key role as the Soviet Union was dissolved, the CSCE was reconvened in an effort to permit East-West dialogue and elements of restraint and cooperation as local conflicts appeared in the regions of the former Soviet Union and Yugoslavia.Uniquely, he was not only the Deputy Head of the US Delegation to the Geneva-Helsinki negotiations, but also the Head of the US Delegation to the negotiation of the “Charter of Paris for a New Europe,” the first attempt to chart new relations in Europe following the end of the Cold War.The Charter became the basis for the organization now known as the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (the “OSCE”).Maresca was a pioneer in seeking to promote dialogue and negotiation on the first local conflict to appear at that time in the post-Soviet space, the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, which remains unsettled more than twenty years later.This conflict was the precursor of a number of conflicts that have developed in the former Soviet space, and continue to fester today.

I met Maresca in March 1993 during my first appearance as a physicist-turned- diplomat at a Congressional hearing on the conflict in the very early stage of my Ambassadorial tenure in Washington, D.C. His insights and analyses regarding the negotiating process during the key years of transition from the height of the Cold War to its conclusion with the Charter of Paris and the Joint Declaration of Twenty-Two States are very relevant today, as the world faces new challenges in the European region, many of which relate to the commitments contained in the Helsinki Final Act and the Charter of Paris.They are especially relevant to the situation in Ukraine and Crimea, and to Russia’s approach to these problems.

The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe—the OSCE—which grew out of the negotiation of the Helsinki and Paris agreements, has become a significant element in the European equation, one which has unique capacities for entering and influencing potential conflicts in the region.The OSCE’s Observers in Ukraine, for example, have played a positive role in maintaining a watchful outside presence.And the potential of this organization goes well beyond what it has been used for up to now.

Maresca has a broad and sophisticated understanding of these complex elements, including the important relationship between Europe and the states of the Caucasus and Central Asia, which have an essential role to play as Europe’s relations with its neighbors to the East become increasingly important.His insights are particularly relevant at this key period of history, when the West is confronted with a newly-active Russia, and an evolving strategic equation in Europe and its neighboring regions.

This book is written as a memoir, and contains new information and many fascinating insights about the development of the CSCE and its evolution into the OSCE.But it also contains some very astute analyses of current events, based on the history of the issues, which surround them.It is, in fact, a commentary on the current situations in these regions, based on the way these situations developed.

It is a book, which should be of great interest to anyone who is interested in the recent history and the current and future state of affairs in Europe, including the Caucasus, Central Asia, and what Russians call their “Near Abroad.”

Hafiz Pashayev

Rector

ADA University

Baku, Azerbaijan

Stresa, 1940

International events,and war,marked my life from the very beginning.I was born in the Villa degli Azalees, in the gardens of the Grand Hotel et des Iles Borromees, a huge luxury hotel which is a national historical monument in Stresa, on the shores of Lago Maggiore inthealpine northern reaches of Italy.Italy was ruled by Benito Mussolini.

My fatherwas thelong-timeDirector of the hotel, and my motherwas an award-winningAmerican painter,cartoonist and designerwho met and married my father while on a travelling fellowship.My older sister and I spent our early yearsat my father’s villa on the grounds ofthe hotel, or at theMarescafamily home in Sorrento, in the South.Marescas have been citizens of Sorrento since the 12thcentury.

It was a glamorous life.My parents spent their social hourswith the manyEuropean aristocratsand otherprominentfigures of the time, who cameto the hotel for their holidays.And of course Ernest Hemingway had left his mark—it is the hotelwhich featuresin“A Farewell to Arms,”where the two lovers start rowing north, to Switzerland, to escape from the First World War in Italy.Thatimaginaryovernight rowing effort, from my father’s hotel to the Swiss shore,was their “farewell to arms.”

But developments in Europeonce againwere ominous.Italyinvaded andannexed Albaniain April of 1939, and when theGermans invaded Poland in September, my parents decided that my mother should take thetwochildren to Americafor the duration of the war, which they thought would last about six months.Under Italian wartimelaws, my father could not leavethe country, so my mother, my sister and IleftGenoaon theConte di Savoia, theiconicflagship of the Italian Line,in the spring of 1940,when I was two years old.Wenever saw my father again.

The trans-Atlantic passage was already perilous; ships were being sunk.The Conte di Savoiahad been guaranteed safepassage toGibraltar, whereBritish citizens disembarked, and onwardto New York—lit up at night sothatitwould not be torpedoed.TheConte di Savoiawas indeed torpedoed, later in the war.

When we arrived in New York we hadsomedifficultygetting off the ship.The Italiancustoms official saidmy sister and I were Italian, andunder the wartime regulationswould have to return to Italy.But the Italian Line was part-owned by my father’shotelcompany,the influential CIGA chainof luxury hotels,and the Captain of the ship knew who we were.He pressed theItalian official, whoshrugged andlet us disembark.

We presented ourselves tothe American Immigration Officeron the pier,and my mother handed overher US passport,issued by the Consulate in Milan,which included her two small children, aged 2 and 4.She had been living in Europe for ten years.After somenervoushesitation,sheasked:“Can you please tell me: what is the nationality of my two children?”

The Immigration Officer took a few moments to replyas he looked over our documents.Then he said, in a classic Brooklynaccent:“Lady,. . .as of now (and he stamped our papers), they’re American citizens.”It was our farewell to arms.

Introduction

“Frontiers can be changed, in accordance with international law, by peaceful means and by agreement.”

Final Act, Helsinki, 1975

Thehistoric evolution of events which has taken place in Europe since the early 1970’s is on-going, and we cannot yet see how it will stabilize,whether it will settle out peacefully orwill continue to be filledwithbloodylocal conflicts.

The division of Europe, as originally conceived at Yalta in 1945, was validated in Helsinki in 1975.But in that same supreme moment of détente the key notion of peaceful change was also accepted and agreed, along with many openings for peaceful movement of people and ideas, to permit the historic evolution of Europe.And it was this acceptance of peaceful change which made possiblethe development ofEuropewe have seensince that time.

Aspects of the European situation which were simply no longer relevant were put aside in response to the popular will.As a consequence, we have seenthepeacefulreunification of Germany,the gradual cementing of the European Union, the release of the countries of Eastern Europe from their domination by the USSR and Communism,the withdrawal ofSoviet andmost Americanmilitary forces,and the break-up ofthe Soviet Union itself into the Russian homeland and a range of“newly independent States”stretching from Eastern Europe to Central Asia.

And there have been other changes, or attempted changes, which were not so peaceful—principally the break-up of Yugoslavia after a prolonged and vicious civil war,the current conflict in Ukraine, and other conflicts which continue and are unresolved.Forty years after it was agreed at Helsinki, the central guideline that any changes in frontiers must take place “by peaceful means and byagreement,”remains the key to enduring peace in the European region.When this rule breaks down,or is ignored,the consequences can be disastrous for the people concerned.

The transformationof theformerUSSR isoneof the central historical factorsinthe situation which exists in Europetoday.In several parts ofthis vast areaethnic tensionscontinue, and some of thesesituations have becomeon-going military confrontations, with no easy solutions in sight.

Thearea which formed theRussian Empire andits successor,the USSR, ispeopled by many national and ethnic groupings, some of which—not all—now have their own statehood.But during the period when Moscow dominated theseregions, Russians migrated, intermarried and gradually settled inmany partsof the vast national territory.History cannot be re-written, and thegradualmigration of ethnic Russians into the areas which Russians call their “near abroad” was and is a historical reality.Millions of Russians transferred their homesto these areas during the two centuries, and more in some areas,of Russian and Soviet domination.The long existence of the Russian Empire, and of the Soviet Union, is a central reality inthe history ofthese regions, even in areaswithquite different cultural heritages, resulting in numerous tensions and inter-ethnic disputes over the years, and some of these disputes have become military confrontations in the aftermath of the breakup of the USSR.

Thesituation in Ukraine is the principal current focus of this on-going evolution, and Russia’s annexation of Crimea is the severest infringement of Helsinki’s key language on changes of frontiers which we have witnessed—a textbookviolation of the concept of changes taking place “by peaceful means and by agreement.”The violent breakup of former Yugoslavia was another violation of this notion of “peaceful change,” but the Crimean episode was more shocking—and ironic—because it was carried outso deliberately, smoothly, andwith such cold disregard for the fundamental conditionality insisted upon by Moscow itself, in its effort to ensure that European borders would be maintained as they were in 1975.

Thehistory of Crimea is special, and this mustalso be taken into account—its transfer from Russian to Ukrainian rule as an anniversary “gift” at a timewhen both countries were part of a single sovereign state, and when no one expected that the USSR would ever break apart.This history is perhaps an extenuating factor, giving the Crimean seizure a special characterand, hopefully, making it unique.

But Russian support for military action in the Donbass is more clearly objectionable, and finds no justification in internationallaw or practice.Russian willingness, even deliberate determination, to support separatist efforts in that regionis directly contrary to the basic concepts of the Final Act, and requires re-evaluation of the entire European balance, as well as the specific conflict situations which continue to exist within the vast former Russian and Soviet space.Russia’s actions in this region call into question itscommitment to adhereto the basic lines of behavior which made it possible to conclude the Cold War and restore normal relations among the countries of Europe and North America, and may open a new period of confrontation between East and West.

The Russian Empire was not the same asother European empires in that the lands colonized by Russia were contiguous to the Russian homeland.This was fundamentally different from the British, French, Spanish or Portuguese colonial empires,which were formed during the same long period of history.This difference has, perhaps,made separation and withdrawalfrom colonized territoriesmoredifficult andcomplicated in the case of Russia.In some cases conflicts arose, rooted in disputes over territory and historical rights to certain regions.

There have been many attempts toresolve theconflicts in the areaduring thisperiod, but those conflicts continueor are dormant, and some new ones have developed.Theheavy-handedrole of Russia in relation to Europe and its other neighboring regions continues to be a key element of regional stability,sometimes stimulating unrest.Thiscan beparticularly worrisome in a time when there is growing turbulence in the nearby Muslim world.Parts of southern Russia include large, restive,Muslim populationsand someseparatist activism.

Russia traditionallyviewsthe so-called “near abroad” areas of the former USSR as regions of specialinterest to Moscow—regionswhere Russia has a naturalprerogative to take initiativesand to undertake,or continue, policies and activities thatare designed tomaintain stability and toprotect the interests of Russia or the ethnic Russian populations of those countries.At the same time the outside world, particularly Russia’s neighbors in Europe, havesought to improve the situation through stabilizing agreements, as well as unilateral policies designed to establish the limits of what is acceptable by Russia in its behaviortoward its neighboring states.There has been considerable caution regarding any possible outside interventions in the former Soviet space, asRussians remain sensitive to the spread of European influence and allegiance into the regions ithas traditionallydominated.

Russia’s relationship with its “Near Abroad” emerged over time as an unspoken, but veryimportant, underlying challenge forthe CSCE/OSCE, as the USSR dissolved and the rules for international behaviorestablished bythe CSCE became applicablealsoto the relations among these newly-independent states.It was only then that the relationship between the concept of statehood, as applied to these new states, and the concept of Russian identity,came into contradiction and became an emotional issueamong Russians in and around Russia itself.The sensitivity of this broad subject has grown as the issues and problems haveemerged andevolved,especially in relation to events in Ukraine,and the probability is that it will continue to grow, in unforeseeable ways.

The OSCE, which was created as a consequence ofthe signing of the“Final Act”at the Summit-level meeting in Helsinki inAugust of1975,as developed,expandedand concretizedby the “Charter of Paris for a New Europe,” also signed at the summit level, in Paris in 1990,and through a number of later agreements,has an important role to play in building mutual understanding and avoiding confrontations so that these regions can develop peacefullyand with mutually beneficial cooperation across national frontiers and throughout the vast European-Central Asian space.

This book is an informal memoirof my personal involvement in some of the efforts, during this long period ofchange andevolution,to harmonize the many elementsofthe processof up-dating the relations among statesin the European region, through the development of the CSCE/OSCE.This on-going conference and international contextwasoriginallya broad attempt torecognize and incorporatethehistorical facts thathave emergedin Europe, and Central Asia,beforeand duringthis period of history, while at the same timeestablishing some recognized standards of international behavior and respect for basic human rights, andopening possibilities forhistorical evolution,freer movementof people and ideas,andmore open,normal relationships among the peoples of the region.

With the evolution of historythe OSCEhas become abroad organizational framework for examiningmultipleissues that relate to Europe and Europeans, anda soft-edged instrumentfor seekingor supportingpeaceful and balanced solutionswhere possible.The use of OSCE Observers in the Ukraine-Russia crisis has been the latest instance in which the OSCE has been involved in such a role.But this type of role is marginal in real confrontation and conflict situations, and questions remain about whattheOSCE can actually do to enhance security and cooperation in Europe.

Thisbook does not attemptto present a broad analytical overview of such issues.It isaverypersonalview,from the inside, of thecomplexmultilateral negotiating processwhich has been evolving within the framework ofthe CSCE/OSCE, especially during its early, formative years.It is focused on my personal activities during that period,from 1970 to the 1990s,and the impressions I hadas the European situationmoved forward, and as my own activities evolved fromwatching over the general development of the institution to the application of its concepts inan attempt to resolve one specific conflict within its region.

I becamethe Deputy Head of the United States Delegation which negotiated the Helsinki Final Actof 1975, and, by an extraordinary turn of fate, was alsotheAmbassador andHead of the UnitedStates Delegation which negotiated the Charter of Paris for a New Europe, signed in 1990.My account of this periodis writtenin the first person as aninformalhistory,reflecting my personal involvement and mycontinuinginterestin this European evolution, because of my own lifestory, which began in Europe andreturned there when I became aUnited Statesdiplomat at the center of this very European negotiating process.

This bookdoes not drawconclusions,which would not in any case be possible because the evolution it observes isbroadand complex, involving many countries and inter-related issues, and is alsoon-going.It simplyaddsto the material which is available to scholars, and to others who are interested, about how thisexpansivenegotiating process moved forward,sporadically andunevenly,thru thisvery activeperiod of history, from what was certainly détente’s supreme moment, in Helsinki in 1975, through thecomplex years which followed and what was universally perceived as the “End of the Cold War,” to the present day.It reflectsthe candidpersonalimpressions and analyses of the author,anItalian-Americandiplomat who was at the center of this negotiating processduring key periods overthree decades, from 1970 until the final years of the 20thcentury.

***

Part I

Brussels, 1970-73

In 1970, in Washington, I was interviewed by the Secretary General of NATO for the position of Deputy Director of his Office, in theInternational Staffof the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, in Brussels.It was auniquepositionand wasreserved for a professional American diplomat.But the Secretary General, Manlio Brosio, was Italian, and wanted someonewho could speak Italianin addition to French, which,with English,constitutedthe two officialNATO languages.Much of Brosio’scorrespondence, as well assome of hismeetings and discussions, took place in Italian, so henaturallywanted someone who could deal with that aspect of the job.The office of personnel in the State Department had done its homework and had discovered that I was born in Italy and was half Italian.My file showed that I spoke French and Italian.I was, in fact, the French Desk Officer in the Bureau of European Affairs at the time.It was a very brief interview.Brosioselected mefor the job,and my transfer to Brussels was arranged shortly afterward.

NATO at that time was consulting intensively on how to open discussions andeventuallynegotiations with the Soviet Union, to ease tensions, to lower the level of military confrontation in Europewhile ensuring Western Europe’s security, and to begin to move toward more normal relations between the twomilitaryblocs—NATO and the Warsaw Pact—which had been confrontingeach other with huge militaryforcessince the end of the Second World War.I was plunged into the principalWesternforum for discussion of these matters—the NorthAtlantic Council, which was comprised ofAmbassadors from all the member states and which met at least weekly to consider the latest developments between Eastand West, and to formulate a strategyfor approaching and engaging with the Soviet Union and its allies to advance the Western agenda.

My immediate boss was an Italian diplomat, Fausto Bachetti, the Director of the Secretary General’s Office, but he was as senior asthe Ambassadors accredited to the Council, so he maintained his own role.I went wherever the SecretaryGeneral went,to assist him,andsincehe chaired the North Atlantic Council, I was in on even the most restricted discussions.

The North Atlantic Council’s agendaduring that periodwas principally focused on the political aspects of NATO’s defense responsibilities—not only maintaining the overall political unity which ensured the general harmony amongthe member states, but also looking for ways to reducethe military confrontation,which was costly, risky, andwas seen as amajor obstacle to the restoration of normal ties among European countries, without putting at risk West European security.The Soviet Union at that time had about 100,000 tanks in Eastern Europe, pointing West, and the countries which were members of the Warsaw Pactwere counted as probableenemies in any military confrontation.It was an acceptedprinciple at NATO that the military forces which faced each otherin Europeshould be reduced, but that this shouldhappen in a way which took account of andhopefully would correcttheexisting imbalance.In other words, the forces on the Eastern side, which were significantly bigger, should be reduced more than those on the Western side, so that the balance would be stabilized and the danger of a military confrontationreduced.This was the origin of the terminology which emergedon the Western side, of “Mutual and Balanced Force Reductions,” or “MBFR,”as the overall Western objective in a negotiating process with the East.Engaging the USSR in discussion and eventuallyinnegotiationson “MBFR” became a principal objective of the Alliance and its member states.

As a parallel matter it was generally thought that there should also be some sort of talks or negotiations on what went under thecommonly-usedheading of “Freer Movement of People and Ideas.”This was the nascent concept of openingmore normalrelations between East and West—to increasecontacts, interaction, travel and exchange of ideas.The two halves of Europe had been cut off from each other since the end of the Second World War,andthe two Germanies, in particular, weredivided by the Wall.Theemergingidea, set forthi.a.in a studyon the “Future Tasks ofthe Alliance,”conducted byBelgian Foreign MinisterPierre Harmel and adopted by the NATO Allies in 1967, was thatastrong defense should be balanced by diplomatic efforts to improve relations with the East.The Harmel Report suggested that the NATO member states shouldbegin to normalize relations between the two parts of Europe—East and West—through increased contacts and greater openness among peoples—“freer movementofpeople andideas,” which became thecommonly-used phrasefor this objective,or just “freer movement.”So this was generally agreed to be a parallelWesternobjective, along with reductions in the military confrontation.

NATO at that time was the principal locus for such discussionsamong the Western countries.The EuropeanUnionof course did notyetexist, though there weresome informal discussionsgoing on amongsome of the European States,and these gradually became more formalized.But the main reason why NATO wasthe center ofthesediscussions and, later, for thepreparationsfor negotiation,was that NATOincluded the US and Canada, without which the Europeans, at that time,felt they would be at a disadvantage in any negotiating process with Moscow.The NATO relationship gave the Europeans confidence that they could negotiate with the USSR on an equal basis.

At the timeI arrived in BrusselsNATO was very actively considering ideas, strategiesand proposals for pursuing theby thenanticipated,discussion and—possibly, orpotentially—anegotiating processwith the USSR.The format, timing and agenda for such aprocess were not yet known, but the Allies wanted to be ready with ideas which had been agreed among them.The spirit at NATO headquarters took much from its military side—strategies and tactics,andfull agreement among the member states,wereconsidered essential, and it was a very serious preparatory process.The basis for agreement on anything at NATO was consensus, and it took time to develop a consensus among such diverse countries on questions of military and negotiating strategy, even more to develop concrete proposals for negotiationon such new subjects as the ones on the “Freer Movement” agenda.It was assumed thatEast-Westnegotiations would take place—it was only a question of time and the format in which they would be organized.So the preparation process was steaming ahead.

I had a privileged position of observation in my postas Deputy Director of the Secretary General’s Office.The NATO International Staff has expanded since those days, but at that time there was only one Director of the Secretary General’s Office, and only one DeputyDirector, and we had considerable influencebecause we spoke in the name of the Secretary General, and were welcome observers in any meeting because it was essential that the Secretary General eventually support and approve agreed Alliance positions.I went to all the meetings—even the most sensitive ones—reviewed all the documents, andcouldinfluence some aspectsof the agendathrough my advice to the Secretary General,by talking to people at all levels in the organizationandeven by approaching diplomatsin the national delegations which had their offices in the NATO headquarters building.I was consideredsomething ofashadowy butkey player, and was sought-after by Ambassadors and their senior staff members.

During my lunch hours—which were very long because Brosio took a traditional Italian attitude toward lunch(which means that “lunch” also includes a period for rest)—I would walk through the corridors of the vast, ramblingNATO Headquarters building to the offices of the United States Mission to NATO, where I had an arrangement with the Deputy Chief of the US Mission, George Vest, under which I had access to his file of communications with Washington.I wouldsit in his office and quietlyread through this file every day during my lunch hour, which gave me full information and intelligence on what was happening in the world, through the many reports from US embassies, andalso onWashington’s perspectives—and instructions—on the main issues of the day.The US Representative to NATO during that period was Donald Rumsfeld, who was close to the White House and the Republican leadership at the time,while Vest was an experienced career official.As the Deputy, and sometimes Acting US Representative to NATO, Vest received even the most sensitive communications, and I was ableto read virtually all of them, in order to fully understand the US position on the issues before the Alliance.

Sometimes Vest would be in his office when I visited to read his communications file.He was a relaxed and philosophical presence,with a great sense of the real importance of things,who gained the respect and loyalty of all who knew him.He was from rural Virginia, and his folksy sense of humor was famous.Healsobrought a canny wisdom to his work, and we gradually became friends, which later ensured mytransfer to the Helsinkiand Genevanegotiations, when they opened.

Brosio was nearing the end of his term as Secretary General, and at one of the bi-annual meetings of the NATOCouncil ofForeign Ministers the Dutch Foreign Minister, Joseph Luns, announced his interest in replacing the Italian.Brosio took this announcement as an indication that he no longer had the full support of the NATO Council, and announced that he intended to step downat the end of histerm ofappointment.The succession was thus clear, and Luns was elected to be the next Secretary General.Brosio was philosophical about the matter, citing the case of the human cannonball in the circus, who had to have“just the right caliber”for the job:“not too small, and not too big.”

ButBrosio washighlyrespected by everyone in the NATOcircle, and he quickly became thefavoritefigureto lead the anticipated negotiations with the USSRand the other Warsaw Pact member states.When Luns took office Brosio was designated as the prospective leader of the comingNATO negotiations with the USSR and its allies.NATOset up a specialoffice for him in Brussels, and I spentmuch of my time bringing him the latest reports and keeping him informed of developments.A communicationwas sentby NATOto Moscow, announcing that the former Secretary Generalwould be NATO’s special envoy to “explore” negotiating possibilities with the Soviets and their allies.Brosio had a detailed mandate on what the Allies were interested in pursuing in a formal negotiating format.It was anticipated that his contacts with the Soviets, and possibly with other Warsaw Pact member states, would help to shape the negotiating process which would follow,and that it would help to maintain the implicit linkage which was emerging, between a negotiation on “balanced” reductions in the military forces of the two alliances in Europe,and a more political negotiation on reducing tensions and creating more normal ties among the European states.The linkage between the MBFR negotiations on force reductions, and the CSCE negotiations on political issues was maintained from this period.Washington was especially pleased with the format for Brosio’s proposed exploration of negotiating possibilities, and Brosio made it clear that he wanted me to go with him on this mission. Time passed,but there was no response from the Soviets, and many people in the NATO group began to conclude that this concept was not going to work after all.

After quite a long lapse of time without any communication,a communiquéwas issuedinMoscow saying that the USSR would not negotiate with a representative of a military bloc.I took the text to Brosio, and heimmediately concluded that he would notbe able tonegotiate on behalf of the Western allies.He told me about his meeting withPalmiroTogliatti, the iconic leader of the Italian Communist Party, the most powerful in Europe.Brosio,a Liberal who was clearly on the right side of the political spectrum butwhowas widely respectedin his countryfor havingrebuilt Italy’s armed forces as the firstpost-war Minister of Defense,was about to depart for Moscow to bethe Italian Ambassadorthere, and paid a courtesy call on Togliatti.They had a friendly discussion about what Brosio might expect in Moscow and the Soviet Union.At the end of the meeting, Togliatti walked with Brosio to the door of his apartment.At the door he said:“Brosio, let me give you a little friendly adviceabout how to understand Communists:always read our statements and declarations very carefully.If you do, you will understand exactly what we are thinking.”Brosio thanked Togliatti, and left for Moscow.

Brosio, the tall and elegant Italian gentleman, with his exceptionally sharp mind and clear ideas,who never went out without gloves, a hat and a cane,looked me in the eye.“I have always followed Togliatti’s advice,” he said, “and it has never failed me.”He concluded that the negotiating missionhe had been named to carry outwas a non-starter, and withdrewfrom Brusselsto his home in Torino, where he was elected as Senator and resumed his political activities.

Europe during the Cold War.©San Jose. Source: Wikimedia Commons.Licensed underCC BY-SA 3.0(s. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en)

The Finnish Invitation

The signal from Moscow about not negotiating with a representative of a military bloc was only one part of theSoviets’emerging strategy for engaging with the West; the other part wastheir encouragement of the Finnish Governmentto invite all the European countries, plus the United States and Canada, to asort of“tea party”in Helsinki,to discuss the format, arrangements and agenda for discussions/negotiations among all the European states, and the USA and Canada.The Soviets knew that they could exercise discipline over the East European countries in such a negotiating process, and they calculated that the Western countries would split and follow their own national inclinations.So direct discussions and negotiations with the full range of European governments, all on an equal footing in one broad conference, looked like a negotiating environment which would be favorable for Moscow.This approach also meant that the Soviets could aim to reach a political understanding about the division of Europe before actually committing to reductions in military force levels, which was their preference.The West European governments were alsointerested in such a political approach, for their own reasons.West Europeans yearned to have normal relations with their neighbors to the East.

The Finnish government’sinvitationconvened all these participants—NATO and Warsaw Pact members and the neutral European states, big and small(even the European “mini-states”—Monaco, San Marino, Liechtenstein, and The Vatican were included)—allexcept Albania,whichsimplydid not respond to theFinnishinvitation—atthe “Dipoli”conferencehall, in Helsinki, on November 22,1972.These became the “Multilateral Preparatory Talks,” sometimes referred to as the “MPT.”In this way, the long-anticipated East-West discussionson Europe’s future,opened.Exempted from this format were discussions and eventually negotiations on “Mutual and Balanced Force Reductions (MBFR),” which were to be the negotiations on military force levels in Europe and would only include the member countries of NATO and the Warsaw Pact.While this was to be a parallel negotiation, agreement to which was considered essential for the opening of the CSCE, it was separate, included only the members of the two military alliances, and proceeded on its own course when it began.

I was still at NATO, stillthe Deputy Director of the Office of the Secretary General,who was nowJoseph Luns,and whose Office Director was Paul van Campen, also Dutch,when the US delegationto the MPT at Dipoli, ledby George Vest, left for Helsinki.The US Ambassadorresidentin Helsinki was nominally the head of theUSdelegationfor this opening round,as often happens in diplomatic practice,but there was no doubt anywhere that it was Vest who led the US participation in the conference, and this became clearer as the Western Allies pursued the discussions about the format and agenda for the coming negotiations.Vest was a canny and amicable negotiator, who in my experience always got what he wanted.But he did it in such a folksy way that his negotiating partners and opponentsoftennever realized that he wasreaching his objectives; theyusuallythought, on the contrary, that they were convincing him to agree with their positions!The beginnings of the caricature of the “low profile” of the US delegationin the CSCEcame from this situation—Vest did not even have the title of Ambassador, and he usually did not present a formal US proposal.He let other national representatives present the NATO-agreed proposals, which he knew very well, and which were usually based on papers drafted in the NATO office in the State Department, and presented as proposals by the US delegation to NATO in Brussels.Most of the Western proposals presented derived from this process.But Vest’s approach was to obtainagreement onUS and NATO objectives through hisinformalpersonal diplomacy.The “low profile” concept suited hispersonalstyle extremely well.He once told me that just sitting in the large vestibule outside the negotiating hall was useful—delegatesfrom other delegations would approach him with their issues, and seek his advice.“If you just sit there,” he said, “people will come and explain their problems.”And this worked well forhim—he became widely respected among all the delegations to the negotiations, forhelping them to resolve their problems and to agree to NATO-based texts.

Everyone at Dipoli understood that avast negotiating panorama was openingwhen the discussions startedthere, but the background ofthecareful preparationswhich had been carried outin the NATO context was not well known.Many western positionsand proposalshad, in fact,been prepared in advance duringvery thorough discussions in Brussels, in the NATO Political Committee and the NATO Council.Vest, without detailed formal instructions (I will come back to this peculiarity later), mustered the disparate Western group through the NATO caucus, and, without making himself into a visible leader, promoted these Western (e.g. NATO-agreed) positions and proposals.This was more formalin the military part of the process—which focused on military “confidence-building measures” (CBMs),and where the NATO positions were supportedin a more disciplined wayby all theNATO members.Butit wasalsothe caseinthenegotiation of thebasic principles of interstate relations in Europe, which would later be the vital vehicle for retaining the possibility of the future reunification of Germany, and the “Basket 3” agenda, which was based on thebroadconcept of “freer movementof people and ideas.” This was thebasic Western approach,which had been developed in the NATO political committee, both in its overall strategic dimensions,and in thevery specific concrete elementsof several proposals.

Manyof the participants in the conference, at Dipoli andlater in Geneva,did not knowthat the Western proposals that lay behind, and explained, the conceptual division into three“baskets”in Dipoli and later in Geneva, derivedlargelyfrom papers and concepts developed in the NATO office in the European Bureau of the State Department (“EUR/RPM”), tabled by the US delegationin the political committee at NATO, which hadthenevolved intoNATO papers tabledby specific national delegationsin the CSCE.This was deliberate, to avoid the appearance of a “bloc-to-bloc” negotiation and to ensure that the neutral and non-aligned states in Europe would support a broad Western position.

This was a key element of the USstrategy—and the broaderstrategyof the NATO allies—in Helsinki and later in Geneva.The Western concepts were represented in these papers, tabled by individual European delegations as their national proposals, and supported by the full NATO group.The US stayed in the background in order tosupport the West Europeans and toavoid making the conference into a US-Soviet negotiation.Roles were taken by different NATO allies, who became the floor leaders inthe negotiating process for the severalwestern proposals, each of which reflected US contributionsin theearlierdiscussions at NATO.

The US side, led by Vest with his extraordinary instinct forlow-keymaneuvering in a multilateral context, reasoned that it would not be useful to make the Helsinki discussions into a US-Soviet negotiation, which it could easily have become.Such a negotiating format would havebeen counter-productive; it would haveput the Soviets on the defensive at the very beginning, and would have alienated the NATO Allies as well as the neutrals.So it was better—much better, as it turned out—to let individual European states take the lead on each of the “freer movement” concepts—this was less threatening for the USSR, because the USA seemed to be disinterested.At the same time these conceptsgenuinelyhad a greater impact for the Europeans themselves, who soughtfreer cross-border flowsof people and ideas, the iconic motto of Basket Three.The Europeans had a much more direct interest in such issues.While there were a few exceptions in which the US delegation, for one reason or another, might take the lead (there waseven one tokenUSproposal in the exchanges part of Basket III, which was developed laterto avoid the potentially embarrassingaccusation that the US had made noformalproposals at all), the general rule was for other Western delegations to table the proposals and to become the floor leadersfor the Western side.

There was another element which ledthe US sideto the so-called “low profile,”whichthe US delegationmaintained for much of the CSCE negotiating process.It can be described here as the“Kissinger factor.”The“Kissinger factor”was the tendency, real or imagined,of Henry Kissinger to personally take up key East-West issues and find solutions forthem himself.Certainly Kissinger was veryeffective andsuccessful in doing this, and later, as I have recorded in my book, “To Helsinki,” he entered the scene, and the CSCE negotiations,to personally resolve one of the most difficult issues—indeed the central issue—in the CSCE’s broad agenda.This wasthe challenge of retaining the possibility of peaceful changes of frontiers in order to keep open, or at least not to exclude, the possibility of eventual reunification of Germany.Recognizing the possibility for peaceful changes in national frontierswas a sine qua non for the Germans, while for the Russians the central objective of the CSCE negotiation was to confirm, at the highest and broadest level,the permanent division of Europe, and therefor of Germany,and to enshrine that division thru signatureby the European Chiefs of State or Government,ina historic all-European summit document,at Helsinki.The fact that the Helsinki Final Act specifically kept the door open for peaceful changes in frontiers became an essential basis for the reunification of Germany in 1990, and an ironic counter-point when, almost 40 years after Helsinki, Vladimir Putinignored the Final Act’s requirement for “peaceful means” and “agreement” to unilaterally annex the Crimea.

Butin the context of the 1970’sit would not have been a true all-European conference if the negotiations were simply conducted by the US and the USSR, over the heads of the European states, and a negotiation of that kind would have created resentment rather than satisfaction.So a considerable effortwas expended by USdiplomats to prevent the conference from becominga US-Soviet negotiation, at least at the public level, even while the Soviets were constantly attempting to pursue such bilateral negotiations.The US delegation, and the US government, affected key issues behind the scenes, in particular the agreement onthelanguage preserving the possibility of peaceful changes in frontiers, which was agreed secretly by Kissinger and Gromyko outside the conference, with the full knowledge anddiscreetparticipation ofthe West German government.Thatagreed language was then introduced anonymously into the CSCE negotiation on the Principles of Relationsamong States, and acceptedwithout objection from any participant because it already had the support of the key players—the USSR, the Federal Republic of Germany, and the USA, which had alsoobtained the concurrence of the two other “occupying powers” in Germany—the UK and France.

There has been much criticism andevenderision of the US strategy of maintaining a “low profile” throughout theoriginalCSCE negotiations—at Dipoli and in Geneva—but Ibelieve that the success of thoseGeneva negotiations, as well as the ability of the CSCE to then hold a summit signing ceremony in Helsinki, was largely due to this deliberately self-effacing strategy, perhaps unique in history for such a dominant power as was the USA in Europe in 1975.

Vest recruited me to be his deputy while he was negotiating in Dipoli.The key US officials who had led the preparatory discussionsin the NATO political committee could not, for variousprofessionalreasons,be transferred to the negotiating effort which now looked like it would take place in Geneva.Meanwhile,withBrosio’sretirement and replacement by Joseph Luns,who was a very different personality from Brosio, my role at NATO had changed.While Brosio was super-attentive tothedetails of every NATO issue or position, Lunshad a different approach.Hetold me once, afterameeting with some regional officials visiting NATO headquarters, that “the only thing that matters is that they go away with a good feeling about NATO.”Of course he was right, in that particular context, but for negotiations with the East we needed to focus on the details as well as the big picture.My own roleat NATObecame more important with this change in the Secretary General’s focus—the Director of the Office and Ihad to watch carefully over all the details, because the Secretary General was only personally concerned with the broad issues and trends.

Over the years, and particularly as a result of the change of Secretary Generaland the fact that I was the only holdover from one Secretary General’s Private Office to that of his successor, I had developed into quite an authoritativeofficial at NATO—despite the fact that my rank in the US Foreign Service was still very low.Inthe NATO structure it was clear that I was a responsible senior official.To illustrate:at one point, while Brosio was still the Secretary General,the unpredictable political leader Dom Mintoff was electedPrime Minister of Malta.At that time NATO had a headquarters on the island, dating fromthe British era.Malta was not a member of NATO, and as soon as he was elected Mintoff sent a telegram tothe Secretary Generalin Brussels, stating that the NATO headquartersin Maltahad to be closed, and all NATO personnel removed from the country, within 24 hours.

I received this telegram, astheone person available from theSecretary General’s office, in the middle ofthe night.Brosiowas away on vacation in the mountains without a telephone number—he did not like to be disturbed while on vacation.The Deputy Secretary General, Osman Olcay,had just left Brussels to become the Foreign Minister of Turkey, and his replacement had not yet been elected.So the Acting Secretary General was a seniorcareer German diplomat, Jorg Kastl, who was the Assistant Secretary General for Political Affairs.Kastl later headed the German delegation at the CSCE Review Meeting in Madrid.I called Kastlat his home,and explained what had happened.He asked me what we should do, and I replied that wereally had no choice; wehad tocomply with Mintoff’s demand.Malta was a sovereign state, Mintoffwas the legitimate head of government, they were not members of NATO, so the case was clear.Mintoffhad asked (actually it was more of an order) that NATO leave, so we had to conform, and leave.In addition, it was worth noting that theheadquarters in Malta, which had been left to NATO by the British, had little unique value.It was not a base for NATO forces, and its functions had been reduced to asymbolic level.Residual NATO functions could easily be transferred to nearby alternativeinstallations, like the major base facilitywe hadin Naples.

Kastl agreedwith my analysis,and I crafted a response to Mintoff, saying essentially that NATO would close its headquarters, as he had requested, and that we would evacuate as soon as possible, butthatit would of course take longer than 24 hours, and requesting a point of contact with whom we could discuss the details.Thiscourse of action, and the response to Mintoff, wereapprovedthe next day atan emergency meeting of the North Atlantic Council, and from thatday we organized to close the NATO establishment in Malta.

This experience turned out to be very useful when Mintoff later held up the final negotiations in Stage 2 of the CSCE with his over-blown insistence that all foreign fleets should be withdrawn from the Mediterranean.

So I was used to taking responsibility, to being creative even without guidance, I knew the issues,maintained my self-control in demanding circumstances,and I was a proven negotiator.I was ideal to be Vest’s deputy, especially since we knew each other well and he trusted me.And within a few days I left for Helsinki to join the US Delegation forPhase I, the Ministerial session to approvethe agenda forwhat was, by then, calledthe Conference onSecurity and Cooperation in Europe.Our delegationto Phase Iwas headed by Secretary of State William Rogers, and Vest insisted that I take a visibleplacein the meeting hall,in order to ensure that I would be recognized by the other negotiators as someone they would have to deal with when Phase II of the Conference, the actual negotiation of what became the Final Act, began in Geneva.

The author at the time of the Helsinki negotiations.© John J. Maresca, 1975.

The US Delegation to Stage 1 of the CSCE, with Secretary of StateWilliam Rogers in the foreground to the right. The author is shown seated, at the top of the photo.© John J. Maresca, 1975.

Geneva, 1973-75

I had a young family, and we up-rooted ourselves from our very comfortable life in Brussels to move to the hotel thatthe US delegation had reserved in Geneva.Our delegation members allhad bachelor quarters, since theywerethere on temporary assignments, without their families—I was the onlyexception, since I was transferred with my family to Geneva for the duration of the negotiations.In fact,I was one of the very few people in the conference who was transferred to Geneva—most delegations assumed that the negotiations would takejusta few months,at most,so they sent their delegates there on short-termassignments, without their families.In addition, it is worth noting that there were almost no women in the conference—1973was still a period when womendiplomats wereveryfew in number.

Isimply drove from Brussels to Geneva, with my family,in our Volvo van.But my family was not happy with the hotel, soweimmediately looked foralternatives, andfound an extraordinary lake-front apartment which had been the home of a European aristocrat—a Spanish Baron if memory serves.In what I later learned was a common Geneva story, he had fled the countryin themiddle of thenight, leaving behindabroadrange of debts.All his material possessions, including the apartment, weretied up incomplexlitigation, and so(consistent with local practice)the apartmentwas rented at low cost, without a lease,on the understanding that the tenants (me and my family)would have to leave immediately when the court reached its decisionon the disposal ofthe aristocrat’s personalpropertyto pay off his debts.But that did not happen while we were there, and so we stayed in that apartment throughout thetwo years ofthe “Phase II”negotiations.

TheCSCEnegotiating process began lazily in Geneva in late September of1973, following the traditionalEuropean vacation habits.We had an excellent delegation, all chosen by Vest—people who were serious and knowledgeable but also unpretentious andgood team-players.They all understood the overall approach, and were responsible for negotiating their part of the overall conference agenda.In many ways thisphase of the CSCEwas a set of related but separate negotiations, which had to be conductedby specialized negotiators,in parallel with each other.For the Principles of Relations between states we had Hal Russell, who was an experiencedlawyer from the legal section of the State Department, who was relieved periodically by David Small; for themilitary issues there was Ed Smith, a State Department Foreign Service Officer on loan tothe Defense Department, and Col.Frank Wilson.Basket two was covered by Bob Drexler, the Counselor for Economic Issues at the US Mission in Geneva, and later alsoJean Tartter,Bob Brungartand Terry Healy.Scientific issues were covered mainly by Walter Jenkins, from the Bureau for Scientific and Environmental Affairs in the State Department,and Basket three responsibilities were divided between Guy Coriden for the sensitive“freer movement” subjects andCharles Stefan on educational and cultural exchanges, which was an established field that everyone wished to expand.All were low-key experts in their specialties