Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

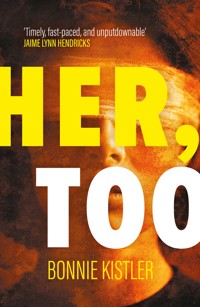

'It is damn well written, and the epitome of a page turner.' - Reader review 'A fascinating look at the complexities of the Me Too phenomenon' - Reader review 'Devoured it!' - Reader review A high-powered lawyer learns firsthand the terrible truth about her client . . . a discovery that propels her on a quest for justice and revenge in this addictively readable thriller. Lawyer Kelly McCann, defends men accused of rape. She's fought to build a successful career as a criminal defence attorney, with a speciality in defending men accused of sex crimes – falsely accused, she always maintains. Her detractors call her a traitor to her gender, but she doesn't care: she loves to win. Kelly's most recent victory is securing an acquittal for a world-renowned scientist accused of sexually assaulting his female employees. But the thrill of her victory is short-lived. That very night she, too, becomes the victim of a brutal sexual assault. And almost as horrific as the attack is the fact that she can't tell anyone who the perpetrator is – not without destroying her career in the process. Kelly has never backed down from a fight and she's not about to start pulling her punches now. As she joins forces with her rapist's victims, for the first time it's not about winning ― these wronged women are out for justice and for revenge. ""Her, Too is a timely, fast-paced, and unputdownable thriller with everything a reader craves. A sure standout for anyone involved in the #metoo movement"" -- Jaime Lynn Hendricks, bestselling author of Finding Tessa ""One of the most unique thriller setups I've ever read, and it keeps moving at warp speed. A must-read."" -- Phillip Margolin, New York Times bestselling author of A Matter of Life and Death, on The Cage ""An absolutely spellbinding thriller. . . . An utterly engrossing and thoroughly entertaining story."" -- Booklist (starred review) on The Cage

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 455

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise for Bonnie Kistler

‘Her, Too is a timely, fast-paced, and unputdownable thriller with everything a reader craves. A sure standout for anyone involved in the #metoo movement’ – Jaime Lynn Hendricks, bestselling author of Finding Tessa

‘[A] page-turner… sharp prose and a ripped-from-the headlines premise… Kistler, a former trial lawyer, brings authenticity to the proceedings… This burns hot’ – Publishers Weeklyon Her, Too

‘One of the most unique thriller setups I’ve ever read, and it keeps moving at warp speed. A must-read’ – Phillip Margolin, New York Times bestselling author of A Matter of Life and Death, on The Cage

‘An absolutely spellbinding thriller… An utterly engrossing and thoroughly entertaining story’ – Booklist (starred review) on The Cage

‘The Cage is a firecracker of a novel: it starts out with a bang and keeps on dazzling until its final, thrilling page’ – Jessica Barry, bestselling author of Freefall and Don’t Turn Around

‘It doesn’t get better than this superb thriller with tripwire suspense, intrigue, and smart women’ – Michael Elias on The Cage

‘[An] exciting psychological thriller… The suspenseful plot careens among various surprising twists toward a satisfying finale… Kistler is a writer to watch’ – Publishers Weekly on The Cage

For all who were silenced, and all who refused to be

Every word has consequences. Every silence, too.

—Jean-Paul Sartre

1

THERE IT WAS: THE RUSH, the thrill, the exhilaration coursing through her veins like molten gold. It hit her the moment she swept through the courthouse doors. Other lawyers felt that rush when they rose to open, or to close, or at the moment the jury returned its verdict. But for Kelly McCann, it was this moment, the victory lap, her triumphal chariot ride around the coliseum while the crowd roared in the stands. It was better than drugs. Better than sex—at least what she remembered of sex. After all, an orgasm was only the payoff of maybe twenty minutes of effort. Whereas this—this!—was the reward for weeks of trial, months of prep, years of sacrifice.

The crowd thronged the pavement in front of the courthouse and spilled out into the street. The reporters had pushed their way to the front; at the back were the TV news vans with their rooftop dishes pitched to the sky like SETI satellites searching for intelligent life. A burst of camera flashes met Kelly as she stopped at the edge of the stairs. Before her was a sea of upturned faces and microphones on poles that stretched like cranes’ necks over their heads. The media was there—her team saw to that—and the protesters were there, too—the media saw to that—with their hand-scrawled placards raised as high as the cameras and microphones. #MeToo and Justice for Reeza and Take RapeSeriously and Believe Reeza. Some of them had been there from the first day of jury selection, and their signs were now tattered and rain-streaked, a proud emblem of their endurance.

On the other side were the counterprotesters, in equal numbers. They held up their own placards: Justice for George, Don’t Cancel Dr. B, and, most prominently, Save Our Savior—hyperbolic perhaps, but not the first time he’d been so dubbed. After all, he was the man who may have cured Alzheimer’s.

Kelly paused to allow the photographers their shots. She was dressed severely, in a black suit and white blouse, tortoiseshell glasses, her blond hair sleeked back in a tight French twist, her only jewelry a wedding band. On her feet she wore not the expected sensible flats but black pumps with four-inch heels. At only five foot two, she needed that extra height.

This had been her signature look ever since her early days in the DA’s office when she learned her colleagues were calling her the Cheerleader. The nickname was probably unavoidable, even if they’d never unearthed her high school history. She was, after all, a petite blonde with a southern accent, a penchant for bright colors, and a tad too much enthusiasm about her work. She couldn’t do anything about her height, and not much about her accent, but she ditched the bright colors immediately. As for her enthusiasm—that died a natural death even before she went over to the defense bar.

Her courtroom team fanned out in a V-formation behind her, like geese flying south. First was her associate, Patti Han, a brilliant young lawyer whose talents were wasted riding second chair beside Kelly. Striding up next was Kelly’s assistant, Cazzadee Johnson, a long-legged beauty whose competence and composure were likewise indispensable to Kelly’s success. Two men brought up the rear: the Philadelphia lawyer serving as her local counsel and the suburban lawyer serving as her hyper-local counsel—both men, both white, and both so nondescript that Kelly routinely confused one with the other. They were indispensable, too, but only because the local court rules required them—a way of protecting the hometown bar from marauding out-of-state lawyers like Kelly. The final member of her team was Javier Torres, her investigator. He was there, too, but not on the courthouse steps. He was on patrol, moving through the crowd like a panther, silky smooth and stealthy.

“For ten long months,” Kelly began, her voice ringing out down the steps and over the street, “Dr. Benedict has borne the awful weight of a false accusation. His reputation has been sullied. His family traumatized. He’s received hate mail and even death threats. And his work—his vital, critical work—has been horribly hampered. That’s the awful power of a false accusation. And perhaps worst of all is that he had to bear all this in silence. The reality of our legal system meant that he couldn’t say a word in his own defense.”

Of course, it was Kelly herself who forbade him to speak, but the crowd didn’t need to know that.

“Today, at last, twelve good men and women spoke up for him. They put the lie to that awful false accusation.” She allowed a smile then, a big beaming smile that broke out like a sunrise over the crowd. “The jury returned a unanimous verdict of not guilty on all counts!”

Her declaration was greeted with boos and hisses from the protesters, but she heard only the applause and whistles from the counter-protesters. Like any good cheerleader, she knew how to whip up her own side to drown out the other side. The technique still worked today. She raised both arms in triumph, and Team Benedict roared its approval and sent the blood singing through her veins.

This moment was her compensation for all she’d sacrificed and all she still endured. For ten years she’d done nothing but defend men accused of sex crimes. Athletes and musicians were her bread and butter, along with the occasional CEO. It was sordid work. The accusations themselves, of course, but also all the borderline-dirty tactics it took to defeat them. All the unreasonable ways of creating reasonable doubt. It left her feeling soiled sometimes, as if her hands were stained with the damned spots of complicity. But this moment scrubbed those spots away. It was like tossing a match on tinder and watching the flames erupt. She was purified by fire, silver in the refiner’s crucible.

She liked to win. She lived to win. It was the entire secret of her success. Her courtroom victories weren’t due to any great brilliance on her part. She had no more talent than the average lawyer. What she did have was this abiding lust for victory.

Early in life she realized that she was never going to be more than a runner-up in either athletic or academic competitions, so she found other ways to use her competitive drive: cheerleading squad, drama club, debate team. Law school was a natural progression, and criminal trial work the natural culmination. Most of her cases she settled swiftly and quietly, but two or three times a year she took them all the way to trial. Always in the best interests of her clients, she maintained, but admittedly it was also to preserve her reputation and keep her profile high. And high was how she felt right now.

“I want to thank the jurors for their service,” she shouted. “They sacrificed more than three weeks of their lives; they had to endure endless hours of testimony and several more hours of thoughtful deliberation. But in the end, they delivered justice for Dr. Benedict. And with it they restored hope for all those people around the world who depend upon Dr. Benedict and his lifesaving work!”

The cheers came even louder then, loud enough to drown out the groans that came from the protestors.

“And now, thanks to those jurors and their outstanding service, Dr. Benedict no longer has to remain silent. Doctor?”

George Carlson Benedict, MD, PhD, shuffled forward to take Kelly’s place at the edge of the stairs. He was fifty, a gray-haired, bespectacled man in a slightly rumpled gray suit. His shoulders were stooped, no doubt from years of hunching over a microscope. He didn’t look like a multimillionaire, but as controlling shareholder of UniViro Pharmaceuticals, he surely was. He didn’t look like an international celebrity either, but he was that, too. It was rare for any scientist to achieve such status, but Dr. Benedict had done it. He was the man who maybe, hopefully, had cured the most-feared disease in the world. He’d already been awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom. The Nobel Prize in Medicine was surely on the horizon.

Kelly stepped aside as her client cleared his throat and droned out his thanks to the jury in his usual low-pitched monotone. The cameras flashed again, and Kelly smiled blindly into the starbursts of light.

When her vision cleared, a face in the crowd leapt into view as suddenly as if she’d zoomed in on it. A glamorous brunette of fifty, tall and handsome, even with her striking eyes narrowed and her mouth twisted with disgust. Kelly froze on that unexpected face for a moment before her vision panned camera-like to the right and zoomed in on another face twenty feet away. It was a young woman this time, quietly pretty with short brown hair and, behind her glasses, deep-set eyes that still looked as haunted as the day Kelly met her. Then her vision-camera panned left, pulled back, and a third face came into focus at the rear of the crowd. Another woman, this one very young, a skinny blonde with timid, bashful eyes. Three different faces, three different women, three different cases with only one common thread.

Dimly, Kelly heard her name spoken. It was Dr. Benedict, thanking her in his robotic voice for all her hard work.

She hadn’t expected to see these women, here or anywhere, ever again. Their cases were done and dusted, checks delivered and cashed, papers signed and sealed. She searched for Javi Torres in the crowd, found him, and raised an eyebrow. He nodded to acknowledge that he’d clocked them, too. As of course he would. He would know their names, too, while all Kelly could remember were their jobs and the dollar amounts: chief information officer, $2.5 million; research scientist, $500,000; office cleaner, $20,000. Money paid to them in exchange for their nondisclosure agreements. The NDA women, she called them.

Her heart started to hammer with a second spike of adrenaline. They shouldn’t be here. They mustn’t be here. This could only mean trouble. She forced herself to take a breath and study each of them in turn. They weren’t holding placards, she noted. They didn’t seem to be part of any group. They weren’t looking at one another. They didn’t even know one another. They couldn’t. So they mustn’t be here to make a scene. They wouldn’t dare.

She searched out Javi again, and he met her eyes and gave a shrug. This was nothing, his shrug said, and her pulse slowed.

Now Dr. Benedict was thanking his wife, Jane, who stood the requisite three steps behind him. She was a plump, rosy-cheeked woman with a mobcap of gray curls, and she gazed on him with eyes aglow behind her glasses.

A disturbance sounded from around the corner as he was thanking the board of UniViro for standing with him throughout this ordeal. A shout rang out, then a chorus of shouts, and part of the crowd broke away and scrambled for the rear of the courthouse. Most of the cameras and microphones followed. Kelly knew what that meant: Dr. Reeza Patel, the alleged victim, was trying to sneak out the back door. But no such luck. The crowd and the media would be there to catch her in the agony of her defeat, this sad perversion of the walk of shame.

A man stepped forward to escort the Benedicts to their waiting car. He was Anton, Benedict’s ever-present shadow. Whether that was his first name or last was never clear to Kelly, nor was his exact job description. He was a towering hulk of a man, bald, with deep forehead wrinkles, like a Shar-Pei.

Kelly signaled her own team to huddle at the far side of the courthouse plaza. She demurred at the fawning congratulations from her local counsel and got down to business. There were housekeeping matters to attend to. Reminders to submit their final statements as soon as possible. The logistics of packing up her files and shipping them back to Boston. There was transportation to arrange, and her assistant, Cazzadee, was already on the phone booking their flights. The Philadelphia lawyer offered to drive them back to their hotel in the city. Kelly declined—she needed an hour to herself—but she pointed Patti and Cazz to the man’s car and promised to meet them at the airport for their flight home.

Patti hesitated and threw an anxious look around the courthouse plaza.

“Don’t worry,” Kelly said. “He’ll make his own way home.”

Patti blushed and ducked into the car. She was in love with Javier and thought no one knew it, while the sad truth was that everyone knew it but Javier.

IT WAS TWENTY minutes before Kelly’s Uber arrived, and she sank into the back seat with a long shuddering sigh. “Tough day?” the driver asked.

Tough day, month, decade, she thought, but she didn’t answer. For three weeks she’d been onstage, her manner and dress and expressions scrutinized by dozens of people. Every word she spoke was consequential. Any slip of the tongue could have been fatal. Any unguarded reaction a signal to the jury that she didn’t want to send. After all that, she was determined for at least the next hour not to perform, and certainly not for the benefit of an Uber driver. He took the hint of her silence and didn’t speak again as he drove away from the courthouse.

In minutes the brick storefronts of the county seat gave way to the gentle hills of open country. It was late September, the last gasp of summer, and the scrolling landscape looked dry and brittle in the late-afternoon sun.

She closed her eyes and leaned back against the upholstery but soon got a crick in her neck. She shifted left then right in search of a more forgiving position, but it was no use. Here was the trouble with the purifying fire of acclamation. It burned out when the acclamation ended, leaving her with cinders in her hair and soot on her hands and the taste of ashes on her tongue.

This case had been particularly sordid. Reeza Patel was a PhD virologist who’d worked on Benedict’s research team. One day last year she’d dared to correct one of his comments, and worse, she’d done it in front of other people. If she were to be believed, he raped her in retaliation. A violent, sickening rape that she described in lurid detail.

But she wasn’t to be believed. The quicksand in the evidence was the fact that Benedict fired her only days before the alleged attack. That could have been the sum and substance of his so-called retaliation, while her cry of rape could have been her own retaliation for having been fired. These circumstances gave Kelly a lot of material to work with. Under cross-examination, Patel dug herself in deeper and deeper until she finally sank. The jury didn’t believe her story, and they acquitted Benedict.

Kelly’s phone was singing in three-part disharmony as alerts for calls, texts, and emails streamed in. She couldn’t turn the phone off—it might be Todd or the children—and she couldn’t ignore it either. Like Pavlov’s dogs, she was conditioned to respond to every ping and chirp. She opened her eyes and opened the phone. Already there was a deluge of emails from reporters, and she deleted all of them without reading.

There was a voicemail from Harry Leahy, her all-but-retired senior partner. Plenty of other septuagenarians had embraced texting over voicemail, but Harry seemed to delight in being a dinosaur, and, sadly, one to whom her fortunes remained tied. “Call me,” his voicemail message said, as if that conveyed anything more than a missed call alert would have.

She didn’t call him. There was time enough for that tomorrow. Instead, she sent messages to Todd and the kids letting them know she’d be home that evening. Todd replied instantly with a thumbs-up emoji, followed by a party-hat emoji, followed by a “whew!” emoji. She couldn’t blame him for that last one. They’d worked out a good division of labor over the years, but when she was out of town, he had to shoulder all the care responsibilities on his own. He deserved a break.

She looked up from her phone and out at the roadside as it blurred past the car windows. The open country had funneled them onto an eight-lane superhighway, flanked by office parks on one side and housing developments on the other. The UniViro campus was somewhere to the left, along with the headquarters of a dozen more pharmaceutical, biotech, and medical device companies. This stretch of suburban Philadelphia was the headquarters of Big Pharma. An employment magnet for bioscientists, it was responsible for much of the brain drain from South Asia, including, Kelly recalled, the parents of Dr. Reeza Patel. The industry had long been tarnished by price-gouging scandals and the opioid epidemic, but thanks to George Benedict, it was suddenly basking in the heavenly glow of public esteem. Science was good again. Drugs were great, and vaccines were miraculous.

She shifted position again. Her right leg had fallen asleep, and she had to shake it out to restore feeling. This had been a recurring problem during the trial. Too much time sitting motionless in courtroom and conference room. She needed to find time for a long run tomorrow.

Her phone buzzed. This was the call she’d been waiting for. “Javi,” she answered. “Anything?”

“Nothing,” her investigator said. He was a former cop, but there was never any bully or bluster in his manner. He reported to her in an even-tempered tone. “They peeled off in three different directions. No phone calls. No signals to each other I could see. They didn’t even glance at each other.”

“Okay. Good.”

“I followed one of them, LaSorta …”

“Remind me—?”

“The tech lady. Hey, guess what she’s driving. A brand-new Porsche.”

Kelly remembered her now: $2.5 million.

“I followed her to see if she was gonna meet up with anybody after, but she headed straight for New Jersey. That’s where she’s living now. I left her at the bridge.”

“Good. Thanks, Javi.”

“I’m gonna hit the road now. I’ll swing by the hotel and pick you up if you’d rather drive than fly.”

She laughed. “Six hours in a car with you? Pretty irresistible.” But even as she said it, she knew there were countless women who would find him irresistible in any setting.

Her phone buzzed in her hand. Another call was coming in, and at the sight of the name, she let out a startled “What?”

“I said, unless you need anything?”

“No, no. Safe trip.” She connected the incoming call. “George?”

Dr. Benedict’s dry voice sounded in her ear. “You didn’t think you’d escape me that easily, did you?”

In fact she did. Their business was over. It was like she always instructed her team: Move on. Don’t look back. No regrets. No recriminations.

“Come to dinner tonight,” Benedict said. “We’re having a few people over to celebrate.”

“Thanks, but my flight leaves at eight.”

“Reschedule for tomorrow.”

“Sorry, no. I need to get back tonight.” She’d been away for three weeks without even a quick trip home on the intervening Saturdays. Lawyers didn’t get weekends off during trial. That time was for witness prep.

“Tell you what,” he said. “I’ll have the chopper fly you home.”

“Oh, thanks, George, but I really—”

“I must insist. For Jane’s sake. She wants to thank you in person.”

She hesitated at the mention of his wife. His bride, he called her—an affectation perhaps, but in this case it was literally true: they’d been married only a short time. And she was such an unexpected choice for a powerful man to make in a second wife. Wife Number 1 had been a brittle blonde who favored short skirts and tall heels, while Jane could have played the sweet-natured grandmother in an old black-and-white movie. She was an RN who’d cared for George’s mother in her final illness.

Kelly considered her their best witness at trial, even though she did nothing but sit silently behind her husband throughout. Her appearance did all her talking for her. She looked like a woman for whom sex was only a slightly embarrassing memory, which had to mean that her husband was the kind of man who didn’t really care about sex very much either. No, he must value companionship, friendship, good character, or why else would he choose a woman like this?

Kelly always wondered what their deal really was. “Well—”

“You’ll be home before midnight, I promise.”

She laughed, a feeble sound of defeat, and accepted his dinner invitation, along with his offers of a car to pick her up and a helicopter to take her home.

Her next call was to Cazz. “Change of plans,” she sighed.

2

BACK AT THE HOTEL, KELLY packed up her room, arranged for her bags and file boxes to be shipped home, and changed into a plain black dress that would have to pass as evening wear.

Benedict said he’d send a car at six thirty, and at six twenty-five, a baby-blue Bentley cruised into the entry court of the hotel. Benedict’s man Anton climbed out from behind the wheel and straightened to his full height like a telescopic crane. Without a word, he opened the rear passenger door, and, without a word, Kelly got in. Anton made her nervous. She could never get a handle on what his role was in Benedict’s life. Sometimes he seemed to be his executive assistant, other times merely an errand boy, and always his driver. Lately he seemed to be his bodyguard, too.

He pulled out from the curb, and she took in her surroundings—the quilted leather upholstery, the burled wood tray tables, all the other luxurious trappings of the car. Benedict was sometimes referred to as a billionaire, though he wasn’t yet. Soon, though. Once the FDA approved his vaccine, the price of his UniViro stock would skyrocket. And once the vaccine went into production, his license agreement with the company would give him a cut of every sale. People around the world would be lining up for that shot. He’d be a billionaire many times over.

They rode in silence as Anton navigated the clogged streets to the expressway. It was thick with rush-hour traffic fleeing the city, and cars were slaloming across lanes and jockeying and jostling on all sides for any advantage. Kelly’s armrest held some kind of control panel, and she was studying the buttons when Anton looked in the rearview mirror and said, “You want privacy screen, yes?”

It seemed rude to say yes, but she said it, and as soon as the translucent panel clicked into place between them, she took out her phone and called home. Six thirty was when she called home every day when she was away, when the kids would be finished with dinner and, she hoped, homework.

“Hi, Mommy,” Lexie answered.

“Hi, honey! I’m coming home tonight!”

“I kno-ow,” the child said.

“How was school today?”

“Fi-ine.” Lexie was using her sulky voice.

“What’s wrong, sweetie?”

“Courtney’s here.”

“Oh?”

“She’s in with Daddy.”

“That’s nice.”

“It is not! She doesn’t even talk. She just looks at him!” Her voice rose, from sulky to indignant.

“Still. It makes him happy.”

“I hate her.”

“Don’t say that. She’s your sister.”

“Ha-alf.” She pronounced the word with enough syllables to make her southern relatives proud.

Kelly changed the subject. “How was your vocabulary test today?”

“Okay, I guess. Hey, Mommy? What does complicit mean?”

“Wow. That’s a pretty big word for fifth grade. Well, it means helping somebody do something bad.”

“Then—what does traitor mean?”

“Oh, honey, you know that one. Like Benedict Arnold, remember? Somebody who hurts his own side to help the other side.”

Lexie was silent for a moment. “I don’t get it. How you could hurt your own sex?”

Kelly felt a flare of panic that her little girl was talking about some kind of injury to her genitals. Then she realized. “Oh. Did Courtney say traitor to her sex?”

“Yes! About you! So what does she mean?”

“It means she disagrees with one of my cases. That’s all. It’s no big deal.” Again she changed the subject. “Where’s your brother?”

“In his room. Probably texting with his girlfriend.”

Kelly didn’t rise to the bait, because she didn’t believe it. Justin was only fourteen, for one thing, and for another, he was undeniably a nerd and proud of it. Awkward and bespectacled, his only interests were science, math, and video games. Which was fine with her. The football-player types peaked early and fizzled out. Nerds grew up to run the world.

“I’ll call him and tell him to come out. And when you wake up tomorrow, guess what? I’ll be there! We’ll have pancakes, okay?”

“Okay.” Lexie’s tone now was grudging, a slight improvement over sulky.

Kelly rang off and placed a call to Justin’s phone.

“Yo, Mercy!” he answered.

“Hey, there, Doomfist,” she said.

These were the names of two of the characters in Overwatch, the video game they played together almost every night. It was the one game Kelly was willing to play, since the violence wasn’t too bad and there were no hypersexualized female characters. She couldn’t stop him from playing those other games on his own time, but she could let him know she disapproved, which was the only real power the mother of a teenager had.

“How was chem lab today?”

“Awesome! We stunk up the whole science wing! It smelled like farts.”

She tried not to laugh. “How’s your Gatsby essay coming along?”

He let out a groan, and all his enthusiasm went with it. “I don’t get it,” he said. “The dude’s uber-rich, right? He can have any girl he wants. So why’s he so hung up on this Daisy chick?”

“Because she’s unattainable. You know how he gazes out across the water at her house? So close, yet so far? He can see her but he can’t touch her, and that kind of longing and frustration leads to obsession.”

“Huh,” he said, and Kelly could almost hear the wheels turning. “Yeah. I can totally see that.”

She smiled. It was nice to know her scientist son could grasp emotional subjects, too. “Listen, do me a favor and keep Lexie company until Courtney leaves?”

“Yeah, yeah.” His tone changed abruptly. Now it was as grudging as his sister’s.

ANTON TOOK THE Gladwyne exit off the expressway, and the noise level inside the car dropped to a hush. Gladwyne was a suburban enclave five miles from the city and one of the wealthiest zip codes in America. The roads here were narrow lanes over gently rolling hills, and they were lined with grand old manor houses of gray stone with slate roofs. The late-summer burn hadn’t touched this landscape. The lawns were lush and green, tastefully irrigated by subterranean sprinklers.

Kelly checked her email before putting her phone away. There were more reporters’ requests for interviews, and she deleted them one after the other. Except for carefully crafted press releases and her verdict-day pronouncements from courthouse steps, she refused all contact with the media. That was her steadfast policy ever since a disastrous interview she gave three years ago following the acquittal of a rap star client. It should have been a softball question: Had she herself ever been the victim of a sexual assault? She should have refused to answer. This isn’t about me, she should have said. Instead she’d replied: No, but then I was never much of a party girl. All she meant was that most acquaintance rapes—which, after all, are most rapes—occurred at or after parties. That was a statistical fact. She almost never went to parties, ergo, she was statistically unlikely to be assaulted. She never meant to suggest that women who went to parties were asking for it.

But that was everyone’s takeaway. Overnight she became the internet’s favorite punching bag. She was called victim-blamer. Slut-shamer. Protestors marched outside her office. Hundreds of women came forward on social media with accounts of attacks they’d experienced in venues other than parties. The workplace, of course. Public transit. Shopping malls. Even church.

She tried to defend herself. The reporter had asked only about actual assault, not other forms of sexual abuse. She’d endured plenty of that. But dirty jokes and leering looks weren’t in the same universe as forcible rape. Those protesters at the courthouse with their #MeToo placards? They were like patients complaining of a hangnail in a cancer hospital.

And now, after all that, here she was, going to a party anyway, and for no reason other than curiosity about Jane Benedict. It was a mystery to her why such a good woman would want to marry that kind of man. Unless she honestly didn’t know what kind of man he was. Kelly had done a pretty thorough job of suppressing that truth.

ANTON SPUN THE wheel to turn onto a long drive that curved around a grove of trees that cast deep shadows into the car. Dusk was creeping into the evening. He circled past a pond covered in lily pads, then around a formal knot garden. One last turn revealed the Benedict mansion.

Institution would be a better word for it. With Greek columns on the portico and an actual rotunda on the roof, it could have been an art museum or the Federal Reserve. And unlike its gray stone neighbors, Benedict’s mansion was built of limestone blocks. Their smooth ivory surfaces were now washed pink in the glow of the setting sun.

The cars of other guests were parked in a cobblestone courtyard, and tucked discreetly around the side of the mansion was a caterer’s van. Anton stopped at the front stairs as the Benedicts emerged from the Palladian double doors. Mrs. Benedict gave a hearty two-handed wave when Kelly stepped out of the car. She’d dressed in somber tones throughout the trial, but tonight she was wearing a rose-colored suit and a pussy-bow blouse. Dr. Benedict wore his usual thoughtful frown and the same rumpled gray suit he’d worn in court that day.

“Welcome, welcome!” the woman cried as she took Kelly’s hands in both of hers. Behind her glasses, her eyes were soft and gentle. “Thank you so much for coming, and for … for everything!”

“Thank you for having me, Mrs. Benedict.” Kelly had to suppress the urge to call her ma’am; she reminded her so much of the church ladies back home.

“Jane! Please! We’ll never be able to thank you enough for all you’ve done.” Jane’s voice held all the inflection that her husband’s lacked. It rose up and down like a singer practicing scales. She’d once been an oncology nurse, and Kelly could easily picture her bustling into a hospital room with a cocktail of chemicals and cheerfully exhorting her patient to sit up now, there you go, nice and easy, now swallow these down. “Oh, what am I doing? Let me hug you!” Jane said and clasped Kelly to her pillowy bosom.

“Let’s take this inside,” Benedict said.

His wife drew back, still beaming, and took Kelly by the hand to pull her into the entry hall, a vast cylindrical space capped off by the dome of the rotunda. From somewhere beyond it came the sounds of party laughter and light classical music.

“I’m sorry your husband couldn’t be here, too.” Jane’s singsong voice echoed across the marble floor. “He’s home in Boston, I imagine?”

“Yes. Yes, he is.”

“Is he a lawyer, too? I’ve been wondering.”

“Yes. Yes, he is,” Kelly said again.

Benedict cleared his throat. “Jane, dear, why don’t you rejoin our other guests? Kelly and I have some business to attend to.”

“All right, but don’t you linger now.” Jane laid a fond hand on his arm, and once again Kelly wondered what held them together, this kindly woman and this humorless man. “Everyone’s dying to meet her!” With a wag of her finger, Jane hurried off on her low-heeled pumps.

Kelly raised an eyebrow at Benedict. “What business?”

“The little matter of your success fee.”

“Oh. Yes.” Harry Leahy managed the financial side of their business, and this time he’d negotiated a bonus for an acquittal. Normally he had to hound clients after trial to collect it. He’d be thrilled to learn that Benedict paid the success fee on the same day as the success. It might even keep him from hounding her about the next big case for a week or two.

“Let’s go to my study,” Benedict said. He ushered her through a doorway on the left that opened onto a long gallery, with a wall of windows on one side and a wall of art on the other. She studied the paintings as she followed after him. They were mostly oils, and mostly featured groups of men stroking their beards or checking their pocket watches while standing beside an examination table where a patient lay supine.

“I see a theme,” she said to Benedict’s back.

He didn’t react. He continued to the end of the gallery and opened a set of double doors. Inside was a stark white space that looked more like a laboratory than a study. The walls were lined not with the expected bookcases but with white library cabinets. The floor was gleaming white marble. The desk was a long slab of thick beveled glass. Opposite it were two white upholstered chairs. Even without windows, the room was dazzlingly bright.

“Have a seat.” He sat behind his desk and opened his checkbook.

Her heels clicked across the marble floor as she made her way to a chair. She was sitting down when the cushion suddenly stirred. She let out a startled “Oh!” and jumped clear as a sleek white cat sprang to the floor.

“Meet Jonas Salk,” Benedict said.

“Hello, Jonas.” She held out her hand, but the cat lifted his nose in the air and stalked away. She moved to the other chair. There was a strange smell in the room, like disinfectant. As if every surface had been wiped down with rubbing alcohol.

“Harry Leahy told me the story, you know.” Benedict didn’t look up from the check he was writing.

“What story?”

“Of how he lured you over to the dark side.”

“Oh. That.” She gave an awkward laugh.

“You were with the DA, he told me, prosecuting sex crimes. Prosecuting his clients, in fact, and winning every time. He tried again and again to hire you. He knew a woman could better defend those cases than he could, than any man could. The optics are so much better. So he offered you more and more money, even a partnership, but you refused him every time. You wanted no part of it. He said you didn’t want to dirty your hands—”

“No, it wasn’t that—”

“—with clients like me.” Benedict looked up then and held her gaze as he tore the check out. It sounded like a bandage ripped from a wound.

She blinked first. “None of his clients were like you, Dr. Benedict.”

With a mirthless smile, he passed the check over the glass slab of his desk. She swallowed her gasp at the amount. It was for $200,000. Their final bill would be a multiple of that figure, but that number reflected actual hours of hard toil by her and her whole team. This check was pure gravy.

“Let’s have a drink to commemorate the moment, shall we?” He stood and opened one of the cabinet doors to reveal shelves of glasses and bottles and a small refrigerator below. “What can I fix you?”

She looked up from the check, still a bit dazed. “Oh, gin and tonic, I suppose. But only a splash of gin. Really, just a tiny splash.”

He reached for a bottle but checked his hand before he touched it. “Why don’t you fix it yourself? You can make it the way you want.”

She nodded, rose, and walked over to the bar, much more comfortable with that arrangement. She opened the seal on a new bottle of gin and tipped a small amount into her glass. A fresh bottle of tonic was in the mini-fridge, and she unsealed that, too, and topped off the drink. He poured himself a dram of Scotch and held his glass up to hers. “To one more success in your career of so many.”

She shrugged as she took a sip of her drink. “I’ve had my share of failures.”

“Not this time, I’m happy to say.”

She returned to her chair, and he took the chair beside her. Jonas Salk leapt from the floor to the desktop and from there another six feet through the air to land on top of a cabinet.

“Speaking of failures,” Benedict said as Kelly sat back and crossed her legs. “Have you ever heard the story of one of the biggest pharmacological failures of all time? Curare?”

“I don’t think so, no.” She took another sip of her drink.

“This was back in the 1940s. Curare was a paralyzing poison that primitives used on their arrowheads. When Western medicine discovered it, they thought it would make a fine anesthesia. Unlike a lot of other drugs used at the time, this one rendered the patient completely immobile. The last thing a surgeon wants is for the patient to flail or even to twitch while he’s got that scalpel in his hand. Curare paralyzed the muscles, you see.”

“Uh-huh.” Her right foot started to buzz once again with that sensation of falling asleep. She uncrossed her legs. She really needed a long run.

“Only one problem,” Benedict was saying. “The patients were still conscious. They could hear everything. They could feel everything. The agony of every slice through their skin and into their organs. And they couldn’t even scream.”

“Oh my God! How awful!” Her other foot was asleep now.

“I’ve developed my own formula,” he said.

“Really?” She stood up to get the blood flowing to her feet. “Whatever for?”

“For situations like this,” he said and caught her as she fell.

The glass slipped from her fingers and shattered on the floor.

“It was in the tonic, you see.” He lifted her in his arms. “One more thing your partner told me. You always order a G and T.”

The horror spread through her as fast as the paralysis. She started to scream, but the air died as a gurgle in her throat. She tried to hit him but now her arms were asleep, too.

He laid her out like a corpse on the glass surface of his desk. “You muzzled me,” he said. “For ten months, you muzzled me. You treated me like a fucking dog.” His robotic voice was gone. Now he spat out his words in a guttural spray. “Like a little lapdog. Sit here. Stand there. Wear this. Don’t do this. Don’t do that. Stay. Heel. Sit up and beg. Like you were the alpha and I was your fucking bitch. Me! The man who cured Alzheimer’s! I’m gonna win a fucking Nobel Prize, and you treat me like that? Like a piece of shit you can’t wait to scrape off your shoe? Well, guess what, Counselor? Now you’re my fucking bitch.”

She was frozen, an iceberg floating in a cold sea under a blindingly white sky. She could feel his hands on her. She could feel him turn her on her side. She could hear the metal scrape of the zipper sliding down the back of her dress. She could hear the clunk of her shoes hitting the floor. He rolled her back, and his face loomed over hers. He pulled her glasses from her face, and she tried to squeeze her eyes shut. She couldn’t.

“What luck,” he said. “That’s perfect. You need to see. You need to see all of it.”

The paralytic had reached her eyelids at the worst possible moment. Her eyes were wide open, fixed and staring straight up at that white ceiling.

“Shall I tell you the best part of this?” he said as he yanked off her dress. “I don’t have to worry about DNA this time.” He took off his suit jacket. “I don’t have to pay any hush money. This one won’t cost me a thing. Because you won’t dare report this. You’ll never speak of this to anyone. Not a soul,” he said as he slithered off her underwear. “Because everything you proclaim, everything you stand for would be ruined if you admit that one of your clients is actually a rapist. Your reputation would be trashed. You’d be humiliated as badly as you humiliated me. No more high-profile, big-money clients for you.” He spat that out as he unhooked her bra. “Your high-flying career would be over. And the DA would never take you back after all the things you’ve done. Even if you could afford to go back, which you never could, not with the exorbitant costs of running your household. So you see, Counselor”—he sneered the word—“that’s my revenge against you. Now you’re the one who’s muzzled.”

His face hovered over hers, twisted and ugly in his hatred. She tried with every ounce of strength she had to close her eyes and shut it out. But she couldn’t.

She could see everything.

She could feel everything.

From his perch on top of the cabinet, Jonas Salk tucked his front paws under his chest and watched what happened next.

3

Reeza Patel

I WAS IN A CAR accident last March when my little Honda was rear-ended at an intersection. It wasn’t entirely the other driver’s fault (a fact he was quick and loud to point out when he jumped from his car). I’d failed to proceed after the light turned green. I’d simply idled at the intersection, staring at the windshield in a blind fog.

That fog had descended often in the days immediately following the Incident. (The Incident was how I referred to it even in my own mind. Anything more descriptive than that might make memories erupt.) But the Accident happened months after the Incident and wasn’t triggered by anything I could identify. I was simply driving home from the store. Then suddenly I wasn’t. Driving, that is. I was sitting at a green light on a busy road. And was slammed into from behind with a force strong enough to propel me into the intersection, where I collided with another car and my airbag deployed.

My symptoms arrived with a fury the next day: back and shoulder pain, a pounding headache that began at the base of my skull and traveled up over my cranium, and a neck so rigid it felt like my cervical vertebrae had been welded shut. My doctor dismissed my condition as merely whiplash and prescribed Tylenol. When the symptoms grew worse, he sent me to physical therapy. When that didn’t help, when the pain was so crippling I could barely see, he suggested it was psychological. (This is often the case with soft-tissue injuries; in the absence of readily ascertainable physical evidence, medical science defaults to all in your head.)

(The same proved to be true in the legal world. In the absence of solid forensic evidence, did it really happen? Or was I only imagining it? Or worse, making it all up?)

It took persistence in both cases. I returned to the doctor again and again with the same complaints until he finally relented and prescribed an opioid (albeit in the lowest possible dosage). And I returned to the district attorney again and again until he finally relented and obtained a grand jury indictment against George Benedict.

I fought hard for both outcomes. But while the oxycodone gave me some relief, the law gave me none at all.

THERE WAS NO mystery as to why I was remembering the Accident today. My drive home from the courthouse took me through that same intersection. The force of that rear-end collision in March felt like an assault—as if an enemy force had charged up behind me with a battering ram. And it felt like an assault today, too, when the jury foreperson stood up and pronounced, “Not guilty.”

It was exactly like the car that hit me. I never saw it coming. I believed justice would prevail, right up until the moment it didn’t. Maybe it was the courthouse picketers who gave me that false hope. All those women waving signs that said BELIEVE REEZA and ENDSEXUAL PREDATION. (Many of them said #MeToo, but I was less grateful for those. You, too? I wanted to say. Then press your own charges and stop freeloading on mine.)

It wasn’t even a case of “he said, she said,” because he didn’t say anything at all. He didn’t take the witness stand; he didn’t raise his hand and swear an oath to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth; he didn’t endure three days in that box as I did with back and neck pain so severe it brought tears to my eyes.

No, it was only a case of “She said, but she’s lying.” And “Where’s her evidence?” (As if the words from my mouth didn’t count as evidence at all.)

I did have some DNA evidence, but not enough. Because I showered right after the Incident. I knew that was stupid. I was a scientist—a biologist, no less—so I knew not to do that. But the need to clean myself was a physical imperative akin to vomiting; the body had to purge itself.

As a result, there was almost no forensic evidence that Benedict had even been to my apartment. There was no semen. He wore a condom, and he must have taken it away with him, for I couldn’t find it afterward. The police found some of his hair on the couch, along with fibers that matched the tweed jacket he’d been wearing. But his lawyer waved that away. After all, she forced me to admit, I’d worked closely with the man, often standing side by side with him in the lab and at lecterns. His hair and jacket fibers could have gotten on my clothes a hundred times, and I could have been the one who brought them into my apartment.

Then there was the fingerprint evidence, or lack thereof. If he’d actually been in my apartment, he would have left his prints on the doorknob, the counter, anywhere. His lawyer hit hard on that point, probably because my explanation made me look like either an idiot or a liar: Benedict arrived at my door wearing latex gloves and kept them on throughout. Why would I let a man into my apartment wearing latex gloves? his lawyer hounded me. It didn’t strike you as odd, his lawyer said to the jury. (She did that throughout her cross-examination—pretend to ask a question of me that was really only a speech to the jury.) But it didn’t strike me as odd. He wore gloves almost every time we were together. So did I. We worked in laboratories. Gloves were like a second skin to us. We were scientists. But no one on the jury was.

Of course, the bigger question was why I’d opened the door to him at all. He’d fired me; I’d already hired a lawyer to sue him; we were clearly enemies by then. It simply never occurred to me that he posed any kind of physical danger. As a little girl I’d learned to be on guard against men who were too friendly, but not against a man who patently hated me. Nobody ever warned me about a man who looked on me with disgust. I’d thought I was safe from a man who felt that way about me. I’d thought rape was a sex crime, not a hate crime. (Now I knew it was both.)

(Many of my thoughts came in parentheticals these days. The twin arcs of the punctuation marks seemed to encapsulate my most dangerous ideas. That way they could be dispensed in slow-release dosages and absorbed with caution.)

I WAS ALMOST home now, and the pain was gnawing through my spine like a caged rat. The pain triggered my asthma (something else my doctor suggested was psychosomatic). I could feel my bronchioles constrict. I could hear the whistle in every breath, and I groped for the albuterol inhaler on the passenger seat and took a puff.

In my field, in all the sciences, there was accountability. If something went wrong—for example, a sample was contaminated—we traced back every step in the process to determine where the fault lay. Something went very wrong in court today, and on my drive home I thought about where to place the blame.

1. On myself, obviously, for failure to preserve the evidence. (Or for opening the door in the first place.)

2. On the prosecutor, for his lackluster performance at trial. (Worse than lackluster. He seemed absolutely cowed by Benedict’s lawyer.)

3. On the jury. I hated to play the race card, but here were the facts: Benedict was a white man, and I was an Indian American woman. The Constitution guaranteed a jury of one’s peers only to the defendant, not to the victim. This jury comprised six men and six women, nine whites, two Blacks, and one Latinx. No Asians. (Do the math.)

4. On Kelly McCann.

I could stop right there. This was all her fault.

Kelly McCann. Impeccably dressed every day. Abundantly self-assured. Never a blond hair out of place. Perfectly shaped eyebrows that she deployed as supertitles to the words coming out of her mouth—one brow lifted in skepticism, two in surprise, both furrowed in a frown. Glasses Reeza felt certain were more for show than for vision. Thin, cruel lips that pulled apart into a simpering little smile that sent my mind tumbling back to prep school.

My parents sacrificed to send me there, and it was the school that later got me into Harvard. But I hated it. It was full of simpering white girls exactly like Kelly McCann. The cheerleaders, the athletes, the popular girls, all of them so confident that they were liked and admired that they never needed to be nervous about anything. Doors would automatically open for them. Their chairs would be pulled out, by magic or divine right. Girls who never deigned to notice the brown girl in their midst until I won an academic prize—Oh, Reezy, wish I had your smarts! they’d say, in a way that made it sound like intelligence was something rather quaint. Or until my asthma kicked up—You poor thing, they’d coo, then exchange glances that said, Sure glad I’m not defective like this one. (I’d been stupidly flattered when they called me Reezy—a nickname was a sign of affection, right?—until I realized it was only so they could rhyme it with Wheezy.)

In fairness, those girls came by it naturally, since their mothers maintained cliques even more exclusionary than their daughters’. I used to watch them gossiping in the school parking lot, in their golf sweaters and tennis dresses, standing in tight little circles to keep others out even while their voices projected far beyond their boundaries. My own mother would walk by in her sari and sneakers and wish them a good morning, and they’d answer her with little nods and smiles, then burn holes in her back as she walked away.

My parents begged me not to press charges. It would follow me the rest of my life, they said. All my degrees, my academic honors, my research breakthroughs, my publications—all that would be forgotten. Everything I (and they, of course) had worked so hard to achieve, would be erased. I’d forever be known as the woman who accused a great man of rape. They didn’t doubt me, they swore they didn’t. But I needed to get past this, and the only way to do that was to let it go.

They chose not to attend the trial. They didn’t want me to be embarrassed, they said. (I knew it was their own embarrassment that kept them away.)

He wasn’t a great man, but he was a great scientist, and I was thrilled to be working alongside him. So thrilled that I not only tolerated his abusive behavior, I made excuses for it. Of course he was a harsh taskmaster. A genius couldn’t be expected to be a gentle, nurturing kind of boss. Of course he shouted and cursed and once threw a glass beaker at a lab tech. A genius couldn’t be expected to tolerate fools. (And he did pay for her plastic surgery afterward.) Of course we must keep our phones on at all times. Of course we should sleep with them on our chests. He might have an epiphany at any moment, and we should all be alert to receive and applaud it.

I had no objection to any of that. Working at UniViro was a privilege, and worth every indignity. I mean—my God!—we were on the brink of curing Alzheimer’s. (Though we weren’t there yet, notwithstanding the company’s PR spin. We still needed to prove that correlation was also causation, i.e.,