11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Grove Press UK

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

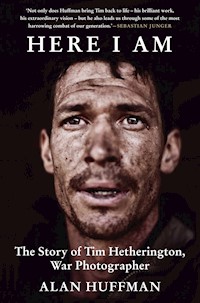

Tim Hetherington (1970-2011) was one of the world's most distinguished and dedicated photojournalists, whose career was tragically cut short when he died in a mortar blast while covering the Libyan Civil War. Someone far less interested in professional glory than revealing to the world the realities of people living in extremely difficult circumstances, Tim nonetheless won many awards for his war reporting, and was nominated for an Academy Award for his critically acclaimed documentary, Restrepo. Hetherington's dedication to his career led him time after time into war zones, and unlike some other journalists, he did not pack up after the story had broken. After the civil war ended in Liberia, West Africa, Tim stayed on for three years, helping the United Nations track down human rights criminals. His commitment to getting the story out and his compassion for those affected by war was unrivalled. In Here I Am, Alan Huffman tells Hetherington's life story, and through it analyses what it means to be a war reporter in the twenty-first century. Huffman recounts Hetherington's life from his first interest in photography and war reporting, through his critical role in reporting the Liberian Civil War, to his tragic death in Libya. Huffman also traces Hetherington's photographic milestones, from his iconic and prize-winning photographs of Liberian children, to the celebrated portraits of sleeping US soldiers in Afghanistan. Here I Am explores the risks, challenges, and thrills of war reporting, and is a testament to the unique work of people like Hetherington, who travel into the most dangerous parts of the world, risking their lives to give a voice to those devastated by conflict.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

HERE I AM

ALSO BY ALAN HUFFMAN

Ten Point

Mississippi in Africa

Sultana

We’re with Nobody

HERE IAM

The Story of Tim Hetherington, War Photographer

Alan Huffman

Grove Press UK

First published in the United States of America in 2013 by Grove/Atlantic Inc.

First published in Great Britain in 2013 by Grove Press UK, an imprint of Grove/Atlantic Inc.

Copyright ©Alan Huffman, 2013

The moral right of Alan Huffman to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of the book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 61185 977 5

Printed in Great Britain by

Grove Press, UK

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.groveatlantic.com

CONTENTS

1 Misrata, Libya, April 20, 2011

2 From England

3 Liberia

4 Escape

5 Monrovia

6 Across Africa and South Asia

7 Afghanistan

8 Hollywood

9 Libya and the Arab Spring

10 Zeroing in: Benghazi to Misrata

11 The Siege of Misrata

12 The Front Line, April, 2011

13 In the Eye of the Story

14 Tripoli Street

15 The Mortar Attack

16 Al-Hekma

17 “That Town”

Afterword

Author’s Note

Acknowledgments

1

MISRATA, LIBYA, APRIL 20, 2011

The walls of the old al-Beyt Beytik furniture store were riddled with holes from mortar and machine-gun fire. Some were the size of the wounds they were intended to inflict. Others were as big as picture windows. In a back room on the third floor the ragged openings framed views of the war zone outside: a distant, solitary figure with a Kalashnikov, silhouetted on Tripoli Street; a burned-out car at the base of a towering palm; a shot-up Pepsi billboard. Viewed as a whole, they evoked a nightmare gallery, showcasing images of war that could get you killed if you stared at them too long.

In late afternoon, sunlight streamed through the holes, illuminating smoke-blackened walls, floors littered with bullet casings, and, in one corner, the rumpled sleeping bags of the Gaddafi snipers. The snipers had shot through the holes at anyone who passed through their field of vision below—mostly young men in head scarves, combat helmets, or baseball caps who darted across Tripoli Street or swerved through intersections in trucks with shattered windshields.

At a little before 4:30 p.m. on the day the snipers were finally killed, the frozen images framed by the holes in the front of the building were suddenly set in motion. A tall, handsome man sprinted past on the sidewalk below, gripping a camera in his left hand, holding the strap of his rucksack with the other to keep it from bouncing as he ran. A few seconds later there was an explosion.

Tripoli Street, like most streets in Misrata, was lined with bombed-out buildings. Earlier in the day, al-Beyt Beytikhad been the scene of a firefight between the snipers and perhaps thirty rebels who had fought from room to room with weapons designed for longer-range combat—automatic rifles and grenades. The result was like an ATF raid on a serial killer’s holdout but with interested spectators and a retinue of photographers who filmed the action on Flip cams and iPhones. Some of the rebels laughed and smoked cigarettes. One arrived with a handful of bottle rockets, grinning as he sang “Happy Birthday.” In one of the photographer’s videos someone laughs nervously offscreen.

At one point in the video one of the rebels balances a piece of broken mirror on a section of angle iron and extends it through a doorway to reveal the snipers hiding around the corner. Behind him, Tim Hetherington peers through his camera at the reflection and is heard to say of the hidden snipers, “One is dead. They’re under the beds.” A bearded man in a headscarf steps forward and begins firing his Kalashnikov around the corner. It is unclear if he hits anyone but he keeps firing.

Hetherington and the other photographers crowd behind him in the hallway, with perhaps a dozen rebels and a few onlookers. When the first gunman steps back, another takes his place and begins firing blindly into the room. The metallic snap of bullets echoes through the building. The rebels chatter in Arabic. Hetherington says, “Fucking hell.” Someone else says, “Oh, my God.” Eventually the rebels set a couple of car tires on fire and roll them into the snipers’ room, hoping to smoke them out.

Al-Beyt Beytik stands a block from where Tripoli Street crosses a bypass known as the Coastal Road on a long bridge that leads toward the capital, about 120 miles to the west. For the past two months Tripoli Street had been a linear battlefield, starting at the center of Misrata and lurching toward the bridge, as the city was besieged by the army of Muammar Gaddafi, bent on stopping the westward advance of the Libyan uprising toward Tripoli. The siege of Misrata, which had brought everyone to al-Beyt Beytik that day, was the climax of the first Arab Spring uprising to escalate into a full-scale war. Misrata, a Mediterranean port of about 300,000 people, was surrounded, and the government forces had positioned snipers—many of them mercenaries—in all of the tallest buildings. Among the mercenaries, it was said, were a group of Colombian women with particularly deadly aim.

Aside from occasional NATO air strikes, Misrata’s only defense came from the kind of men who shot up the interior of al-Beyt Beytik that day—local rebels with little or no military training, people who before the war had been truck drivers, salesmen, artists, office workers, laborers, lawyers, students, or unemployed. In the beginning most did not have guns. Some had arrived on the front lines armed with knives or steel rods. Over time, they managed to ambush and kill a few Gaddafi soldiers and steal their guns, which they used to kill others, acquiring more guns in the process. Meanwhile, weapons and ammunition were being smuggled into the port aboard fishing boats, so that by April 20, 2011, the day they attacked the furniture store, most of the rebels had guns, though not everyone knew how to use one.

That afternoon, as Hetherington sprinted past al-Beyt Beytik, a few dozen rebels and a small group of photographers lingered on Tripoli Street, waiting for what came next, which turned out to be a mortar blast, after a long, relatively quiet period. The bomb exploded on the sidewalk in front of an auto repair garage, scoring the pavement in a star-shaped pattern, sending smoke, dust, and shrapnel into the group of people who stood—or, in Hetherington’s case, ran—nearby. As the smoke cleared, a Spanish photographer watching from across the street saw perhaps ten bodies strewn about and people sprinting for cover. Soon a few cars and trucks emerged from hiding places and sped away. A few vehicles stopped and rebels leaped out and began loading the injured into them to take them to al-Hekma, the city’s only functioning hospital. The photographer across the street, whose name was Guillermo Cervera, snapped three pictures of the aftermath of the explosion with his iPhone, then ran to help. At the scene of the explosion he flagged down a car and pushed two of the photographers, one of whom was bleeding from his chest, into the backseat. The car then sped away. Next Cervera helped two rebels load Hetherington and a second photographer, an American named Chris Hondros, into the bed of a black pickup truck, after which the rebels jumped into the front seat, Cervera climbed into the bed with his injured friends, and they drove away, down the sidewalk and into an alley to a side street that went north from Tripoli Street toward al-Hekma. Hetherington was bleeding profusely from a small wound at the top of his right leg. Hondros, who still wore his combat helmet, was unconscious and had an ugly gash in his forehead.

Where the alley emptied into the side street, the driver saw an ambulance and stopped. After a quick and frenzied discussion, the decision was made to transfer Hondros, who was at the back of the bed with his feet hanging off, to the ambulance. He was the easiest to get out. While the transfer was taking place, Cervera took a photo of Hetherington lying on his back in the bed of the truck, propped against ammunition boxes. Then everyone got back in the truck and the driver tore off down the sandy street in a cloud of dust. As they sped toward al-Hekma, Hetherington began to lose consciousness due to loss of blood. Cervera took his hand in his own and spoke to him soothingly, trying to keep him awake.

The streets passed between walled residential compounds that had been subjected to frequent shelling and sniper fire so that the routes were full of obstacles—downed power lines, destroyed cars and trucks, the rubble of collapsed walls. Everyone other than the fighters was long gone. The pickup and the ambulance behind it rarely slowed, though at one point the truck’s driver had to jam on his brakes and swerve to avoid colliding with a car full of rebels that appeared out of a blind side street. Eventually—it felt to everyone like an eternity—the warren of sandy streets led to a paved road, which in turn led to a series of checkpoints that the rebels quickly waved the vehicles through, across several roundabouts and, finally, to the avenue that led to al-Hekma. On the final stretch there was a series of speed bumps, which jostled the injured men. Some fifteen minutes had passed by the time the pickup and the ambulance careened into the narrow driveway of the small hospital, where a tent had been set up in the parking lot as an emergency room.

Alerted over the radio that two more Western photographers were on the way to the hospital, a group of rebels, nurses, and doctors rushed out to meet the vehicles. They pulled Hetherington from the bed of the truck, loaded him onto a gurney, and hurried with him into the tent. Others removed the stretcher on which Hondros lay and rushed him into the main hospital, to the small ICU.

Inside the tent were the other two photographers who had been injured in the attack—an American, Michael Christopher Brown, who was one of the men Cervera had pushed into the car, and a Brit, Guy Martin, who had been transported in another pickup truck. There were also perhaps six injured rebels, some with equally grave injuries, though they would not be mentioned in later news accounts. At least three rebels were dead, or soon would be. Hetherington had by now lost consciousness, and was possibly dead, but for ten or fifteen minutes a group of Italian and Libyan doctors pushed violently against his chest, trying to resuscitate him. A rebel photographer named Mohammed al-Zawwam filmed the scene with his video camera, pushing his way through the crowd, now and then bumping into someone so that his footage veers wildly from the men on the gurneys to the floor to the back of someone’s head. At the point where he comes upon Hetherington, we hear him say, off camera, “Tim,” in surprise and recognition. He then focuses on Hetherington’s body for a long moment and zooms in on his face, close enough to pick up the stubble on his chin.

As al-Zawwam filmed, a Brazilian photographer with a dark, manicured beard, whose hair was trimmed into a kind of soccer mullet, observed him getting in the way of the doctors and nurses and kicked him. A moment later, the Brazilian, whose name was André Liohn, saw Cervera standing off to the side and said, angrily, “I told you, you shouldn’t have been there.” Liohn would later post a message on his Facebook page that said, “Sad news. Tim Hetherington has died just now in the Misrata hospital when covering the frontline, Chris Hondros is in a serious state.”

2

FROM ENGLAND

In the summer of 2003 a Liberian rebel named Black Diamond was roaming the remote garrison of Tubmanburg, Liberia, when she saw Tim Hetherington sitting on the balcony of a house that belonged to her leader, General Cobra. At the time, the West African nation was in the midst of its second civil war in a little more than a decade, and Black Diamond was in charge of a group of female fighters. Her life had an ecclesiastical aspect. She had joined the rebels after being raped at seventeen by government soldiers who had killed her parents, and she was known as a relentless, fearsome fighter. Later in the summer she would be featured in a BBC report called “Liberia’s Women Killers” for which she posed with a pistol and an AK-47. She was rumored to have castrated enemy soldiers, though she declined to publicly verify or deny the claims. Her exploits eventually became so notorious that some Liberians thought she was a myth.

In that context, the arrival of a tall, handsome, stranger, a white man who seemed to be having a good time, struck her as odd. Black Diamond had heard that two white men were scheduled to arrive in Tubmanburg to film the rebels during their assault on the Liberian capital, Monrovia, but by the time the journalist Sebastian Junger interviewed her in 2011 for a documentary film about Hetherington’s life, after he’d been killed in the North African nation of Libya, she had transformed Hetherington into something of a legend, an apparition. In the lilting patois of Liberian English, she said her first thought was, “Wow, what a strange guy . . . what a handsome man doing in the lion den?”

Black Diamond and her female compatriots, including many who had likewise been raped by government soldiers, were part of a rebel group known as LURD, which stood for Liberians United for Reconciliation and Democracy, a lofty name that belied a violent history in a place long noted for violence. Hetherington and the filmmaker James Brabazon had traveled to Liberia to accompany LURD during its second assault on Monrovia. Junger would later become a friend and professional collaborator of Hetherington’s and, in the summer of 2003, had been reporting on the war from inside Monrovia, on the other side.

Hetherington stood out in a crowd, and his appearance unsettled Black Diamond, she said. She was unsure why such a man would give up a comfortable life to put himself at risk in someone else’s civil war. During his eight years as a photographer covering numerous wars, conflict zones, and other places of human disaster, which began that summer in Liberia, Hetherington would ponder the question himself. It seemed at times as if war photographers were vultures and, at others, part of the conscience of the world. Going back and forth between war zones and the comforts of home tended to make such photographers perennial outsiders.

The simple answer is that a war photographer is someone who makes his living photographing wars—someone like Robert Capa or Larry Burrows, who put their lives at risk to illuminate what was happening in the world’s dark and violent recesses, and meanwhile brought high drama to the mass media. Hetherington was among the best known photographers covering war at the time of his death, but his interests extended beyond what journalists call “bang-bang” photos. Often his war photographs are not of combat itself but of faces and telling details about the people caught up in the conflict. He tended to immerse himself in their world, and to stay there longer than most of his peers, who tended to show up, snap dramatic photos, and move on. Wherever Hetherington was, he was always there. He preferred to describe himself as a maker of images, someone who told stories through a variety of media, including still photography, video, and written narratives, and he saw himself as an artist with a strong humanitarian bent. His aim, as he later put it, was to try to explain the world to the world. As it happened, there was no better place to do that—to show what mattered—than in a war zone.

The nexus of conflict photography as a journalistic discipline was, in fact, art, though its original intent was more about military strategy than the kind of storytelling that characterized Hetherington’s career. The earliest precedent for war photography is generally considered to be the work of a Dutch painter named Willem van de Velde the Elder, who in 1666 rowed out in a small boat to sketch an encounter between the Dutch and British navies during what was known as the Four Days Battle. Van de Velde later used his drawings as the basis for heroic oil paintings, as well as to acquire a commission from the British government to sketch naval battles for official review. Numerous other painters followed suit in subsequent wars. The British war photographer Roger Fenton also started out as a painter in the mid-nineteenth century. After visiting an exhibition of photography in London in 1851, he studied photography for two years, then got an assignment to cover the Crimean War, also for England and, again, for official, strategic purposes. In the United States the painter Mathew Brady started photographing in the 1840s and later became famous for his photos of the American Civil War, including graphic images of corpses, which was a new phenomenon that brought home the reality of war in a less stylized, sanitized format. Both Brady and Fenton were limited in their choice of subjects by the slowness and awkwardness of their equipment; because of the necessary length of exposure times subjects had to be still, which meant that they primarily photographed landscapes, buildings, and people who were posed, much as they would have been for a painter. As a result, the first photographic images of war were, like many of Hetherington’s own combat portraits, carefully framed and comparatively static. Their subjects—the live ones, at least—had time to think about how they were being recorded and tended to consciously play the role. So did Fenton and Brady, who in some cases staged their photos.

War photographers hit their stride during World War II, and by then most had their own agendas—to share the drama with the public. Among the first well-known war photographers was Robert Capa, who covered the Spanish Civil War, World War II, and the First Indochina War, where in 1954 he was killed by a landmine. The role of war photographers became pivotal during the Vietnam War, when photographers such as Burrows—another Brit who, like Capa and Hetherington, died at war—brought home powerful images that not only entertained the public but illustrated precisely and on an intimate level what was at stake in war.

At the time Hetherington traveled to Libya to cover that country’s 2011 revolution, technology had enabled instant media coverage via satellite uplinks and websites, which further amplified the demand for war images, as well as the risks associated with producing them. But in the summer of 2003, when Hetherington and Brabazon arrived in Liberia, video was just coming to the fore as a critical component of war coverage. So in addition to his video cameras Hetherington carried comparatively antiquated still cameras that were more suited to studio work; the combination enabled him to cover the conflict both on the cutting edge of journalism and in the creative, timeless style of an artist.

As Hetherington’s career unfolded, most people described him as a war photographer, but he said he had “no interest in photography, per se.” Instead, he was interested in the power of images—photographs, films, drawings, paintings, fly posters glued to utility poles, spray-painted graffiti—to spark dialogue about what was happening in the world. Photography was the primary tool at his disposal, and it gave him an outlet for both his creative and his humanitarian interests. It also provided a potential means for exorcising internal demons that he never fully described other than as “a destructive tendency inside myself.” War photography required a certain remove, a personal distancing from the core conflict that counterbalanced the photographer’s physical proximity. Yet as Hetherington told one interviewer, “I think the important thing for me is to connect with real people, to document them in these extreme circumstances, where there aren’t any kind of neat solutions, where you can’t put any kind of neat guidelines and say this is what it’s about, or this is what it’s about.” He wanted to show what was happening to people beyond the firing of weapons.

Timothy Alistair Hetherington was born in Birkenhead, near Liverpool, in 1970, to a family of comfortable means—father Alistair, mother Judith, brother Guy, and sister Victoria. As a boy he had a notably inquisitive mind and showed talent as an artist. At age ten his parents enrolled him in a private boarding school run by Jesuits known as Lancashire Benedictine, at Stonyhurst College, where he was appalled by the frequent bullying and use of corporal punishment, as he later told Junger. He learned to loathe conflict yet over time felt compelled to understand it; he became, in Junger’s words, a “bright spirit drawn to dark places.” At his religious confirmation, Hetherington added a third name, Telemachus, after a central character in Homer’s Odyssey, the son of the Greek god Odysseus who searches for news about his father while he was at war; Telemachus was also the name of a saint who was stoned to death in a Roman amphitheater after trying to halt a gladiator fight.

Early on, Hetherington had ideas of becoming a writer and studied English literature and the classics at Lady Margaret Hall, a college of Oxford University. After graduating in 1992, he used a £5,000 bequest from his grandmother to travel for two years in India, China, and Tibet, feeding his curiosity about the lives of people in unfamiliar circumstances. His family rarely heard from him during his travels, receiving only a handful of faxes, until he showed up back in England, a patient of the London School of Tropical Medicine, suffering from a host of tropical diseases. After being hospitalized for about a month he took a minor editing job, which he found unsatisfying, and then made the decision to study photography. He later said he’d had an epiphany after returning from India, which led him to want to “make images.” He was profoundly influenced by the 1983 film Sans Soleil, directed by Chris Marker, which showed how powerful film, still photos, and a combination of the two could be. “That film was a real turning point,” he said.

Because photography was easier to get into on his own than film, Hetherington began taking night courses in the discipline while working at various jobs, and eventually he enrolled full-time in photojournalism graduate school at Cardiff University in Wales. There, he was known as a driven student who attracted attention when he walked into a room—he was tall, good-looking, and affable and had a keen sense of humor, could party with the best of them, and sported a mass of long dreadlocks that he often tucked inside an oversized skullcap. He showed particular interest in photographing sports and health stories and had a tendency to immerse himself in his subjects: a photo essay about people who suffered from Alzheimer’s and dementia required him to spend long hours for several days at an adult day care center. When he set out to do a photo essay on youth violence, he hung out at the emergency room at a Cardiff hospital—this in an era when a photographer could do such things without privacy restrictions—to observe when young men arrived whose injuries had resulted from fights. He was also exploring multimedia, a fairly new concept at the time. When Stephen Mayes, an external examiner of student projects at Cardiff (and later a friend of Hetherington’s), reviewed his work he was “blown away,” he said. It was powerful, original, and pushed the limits of conventional photography. Hetherington’s final class project at Cardiff, in 1997, was an essay on alcohol-related violence, as observed in a hospital emergency room. Afterward, he began getting freelance photography jobs around London, shooting for theBig Issue,a magazine sold by homeless people, and theIndependentnewspaper. He was comfortable moving freely between very different worlds. At Oxford he had attended formal dining clubs in white tie and waistcoat; at Cardiff, he was the dreadlocked guy; now he was exploring every facet of the world around him for whatever publication would pay him to do so.

Then, in 1999, he began to find his focus while covering the Millennium Stars, a Liberian soccer team that was touring the UK. The team members were former combatants in the first Liberian civil war, which had ended three years before. Hetherington had called the trip’s sponsor to see if he could arrange a ride on the tour bus. He was told the team was looking for someone to film them back in Liberia. “And that’s how it all began,” Hetherington later said. In exchange for filming, his expenses—for travel, film, and lodging—were covered but little else. The journey proved worthwhile. His photos were picked up by several magazines, and along the way he fell in love with West Africa and began following what was happening in the region more closely. “When I went to Liberia, it just blew me away,” he said. “I’d never experienced a country like that before in my life.”

From Liberia he traveled to neighboring Sierra Leone, which was experiencing its own civil war, also to photograph soccer players. Soccer was one of the few pastimes that people in war-ravaged nations such as Liberia and Sierra Leone could take joy in. Though it provided a needed diversion, Hetherington said of a later photo essay on the subject that it was a story about war “disguised as sport.” Hetherington did not directly experience combat but he felt its presence in Sierra Leone, as he had in Liberia. He shot a series of portraits of people who had been blinded by rebels and came upon a choir of blind students who inspired him to arrange a UK tour for them. The choir members, mostly children (though there were a few adults), had been blinded by childhood diseases or by torture and abuse during the civil war. Hetherington abhorred the inhumanity of war yet was attracted to understanding its origins and ramifications. In helping to arrange the blind choir’s tour of the UK he hoped to show the impact of the West African wars and, in turn, expose the students to the outside world.

He happened upon the Milton Margai School in Freetown, Sierra Leone, and saw parallels between the school’s blind choir and the Millennium Stars, because both involved young people dealing with handicaps or other hardships induced by war. Both of the underlying wars involved child soldiers and, for most Westerners, were bizarre episodes that also seemed to them reassuringly foreign. Having been exposed to the sometimes sadistic bullying at his English boarding school, Hetherington was curious about why one child might end up as a victim of war and another the victimizer. At the same time, he saw an opportunity to replicate the soccer team’s UK tour, this time with the blind children’s choir, and he began enlisting sponsors and helping the school organize it. The August 27, 2003, South Wales Echo announced the choir’s tour under the headline “War-Hit Children Sing for Us.” The choir members had endured eleven years of a particularly brutal war, and many had known nothing else. Hetherington, who acted as the choir’s spokesman, told the South Wales Echo, “7,000 people were murdered, thousands more abused, and half the city destroyed.” The tour, Hetherington told the newspaper, was a way to begin “rebuilding their lives and healing the mental scars.” For his part, he accompanied them on the tour, kept them entertained, and even washed and ironed their forty stage costumes before their concert at Westminster Abbey.

Corinne Dufka, who at the time worked for Human Rights Watch in Freetown, met Hetherington while traveling back and forth between Sierra Leone and Liberia, covering the conflicts and interviewing refugees. When she heard of his association with the Milton Margai School, she said, “I loved him for that. He wasn’t one to go for the easy, obvious target.” Most Western journalists were fixated on what she called Sierra Leone’s “signature atrocity”—the rebels’ penchant for hacking off their victims’ arms or legs. The blind children had been largely overlooked and forgotten. Some of the choir members, she said, had had burning oil poured into their eyes because they could not stop crying after watching family members killed. In addition to organizing the tour, Hetherington introduced the blind choir to blind children in the UK through a pen pal program, and though he was understandably proud when he won a World Press Photo award for his portraits of the choir, his relationship with them—they called him Uncle Tim—“touched him on a far deeper level,” Dufka said.

Hetherington’s decision to move beyond the blind choir and the Millennium Stars to document the underlying conflicts was part of a natural progression, Brabazon said. It was “almost as if, by being there and interested in the people, he kind of got sucked into it,” he said. Through the blind children’s choir, Hetherington had seen the direct consequences of war. “He saw it physically, visually, graphically, literally on the faces of the children he was photographing,” Brabazon said. “But what he didn’t see was the mechanism of that violence. He didn’t see how it was inflicted and by whom, and I think that what he went on to do in West Africa, when he came to Liberia with me, when he stepped into the middle of that war, was to see very clearly who was perpetrating these acts of violence and why. I think that the blind school was the beginning of the journey for Tim in some ways. It was the beginning of his journey in war and Liberia was the next logical step.”

Because the Liberian president Charles Taylor had funded the rebels who committed the atrocities in Sierra Leone, “there was a very strong connection, both metaphorically and literally, between the war in Sierra Leone and the war in Liberia,” Brabazon said. “And I think that Tim understood very, very quickly, you couldn’t really understand what had happened in Sierra Leone, you couldn’t understand what was happening in Ivory Coast, next door, you couldn’t understand what was happening in Guinea unless you understood what was happening in Liberia. And I think that’s what drew him back there, to understand what the center of this regional maelstrom was. Who was behind it and why were they doing this?”

The same year he had first visited Liberia and Sierra Leone, Hetherington traveled to Sudan and, in the years afterward, to the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Ivory Coast, Namibia, Nigeria, Burkina Faso, and, again, India; he also covered the elections in England and photographed Afghan refugees following the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan in the wake of the events of September 11, 2001. He used freelance assignments and gigs for charities and NGOs to explore the lives of people who, for the most part, were struggling with seriously adverse circumstances. By 2002, the year James Brabazon’s first documentary film about Liberia’s LURD rebels was released, Hetherington was fully vested in Africa. The more he considered the harsh consequences of war, the more he wanted to understand its root causes.

During his time with Brabazon a theme began to emerge that would define much of Hetherington’s work: the complex, persistent, and often baffling relationship between young men and war. War is undeniably grueling, so it was not surprising that young men played a key role. But what, Hetherington wondered, prompted them to fight, knowing they might die? Often, he found, it had nothing to do with the core reasons for the conflict. And why did so many of them relish combat? Liberia seemed a good place to find out, because he was familiar with the country and its second civil war was now under way. Though women too were drawn to battle, such as Black Diamond and her female fighters, and some of the rebels and government soldiers were mere children, it was the young men, Hetherington later said, who seemed hardwired to fight. Ultimately, he said, young men were used as tools in a violent political process as a direct result of their genetics and chemistry.

After seeing Brabazon’s film, Hetherington cold-called him to say that he wanted to accompany him to Liberia when and if he returned. As Brabazon recalled, he was at first uninterested; he had received a phone call from a total stranger who basically said, “Hi, you don’t know me. My name is Tim Hetherington, and I’d really like to come to Liberia with you and take photographs of the rebels.” Brabazon initially said no, that it was his story and he was not interested in sharing it. But then Hetherington informed him that he already had a Liberian visa, “which was like gold,” Brabazon said. “So I had the idea to divide the story, me with the rebels and Tim with the government troops.” When he met with Hetherington to talk things over, Brabazon said he realized that “I actually really like this guy.” He decided to hire Hetherington as a cameraman and associate producer, with the understanding that he could also take still photographs for his own use. Meanwhile, Brabazon got a call from the documentary filmmaker Jonathan Stack saying he wanted to go, as well, so Brabazon developed a plan for him and Hetherington to film from the rebels’ side while Stack would film inside the city. Brabazon and Stack would coproduce the resulting documentary.

Brabazon and Hetherington spent a good bit of time hanging out together in the month following their meeting—triangulating, taking each other’s measure before setting off for Conakry, Guinea, the final point of embarkation for what proved to be an intense, bizarre, and often terrifying journey. The Liberia trip was “kind of like our Rubicon,” Brabazon recalled, when talking with Junger for the documentary film about Hetherington (which Brabazon coproduced). War, he said, is “like a pressure cooker, you know? It takes human relationships, puts them under a lot of strain, and accelerates them, and rather than you spending two or three months to discover that you don’t particularly like someone you’ll know like that.” He snapped his fingers. “And rather than spend a year getting to know someone and become mates with someone it can happen overnight.” Finding themselves alone together in a foreign jungle, during a war, and having surrendered their trust to a mercenary guide and a group of armed rebels who were intent on capturing a heavily armed city, there was “very little room for bullshit,” Brabazon said.

Brabazon was encouraged that Hetherington had been to Liberia before, as well as to Sierra Leone, which meant that he knew how to get by in West Africa, though at the time he had never experienced armed combat. What mattered most was that Hetherington was game, even if he was a mannerly Oxford-educated type—Brabazon was also a Brit—prone to intellectual discussions and ruminating about truth and beauty and the aesthetics of his craft.

Hetherington loved what he knew about Liberia, but he knew there was no way to predict how he would react once the bullets started to fly. So as they hung out in Tubmanburg, and later as they advanced with the rebels toward Monrovia, he and Brabazon often talked about what would likely go down once the fighting started and the proper way to respond. Brabazon told him, “Stay close to me, do as I do. If you need to tell me something, physically grab me. If I don’t respond shout at me. Worst case, lie flat on the floor.” Hetherington listened to Brabazon’s instructions in silence, processing the information. Afterward, Brabazon said, “He was very focused. He was never afraid to ask questions, never pretended to be more comfortable than he was—exactly what you want from someone in that situation. If he was afraid, he said he was afraid.”

Unlike most photojournalists, Hetherington wasn’t enthralled with using the latest technology. He owned a digital camera but decided not to take it with him to Liberia. He preferred to use his proven yet comparatively antiquated film cameras: a Mamiya Rangefinder and a Rolleiflex box camera, a type that had been in use since the 1930s, which required winding up and had a top-mounted viewfinder in which the image was reflected upside down. The images taken with such cameras were more textured and defined, Hetherington said, as opposed to highly pixilated, color-saturated digital images. Still, as Brabazon observed, the old-fashioned cameras tended to be difficult to use even on a tripod in a studio, much less during running combat or in the backseat of a car barreling through a firefight. Brabazon satisfied himself that at least Hetherington knew what to do with a video camera.

When Brabazon was deliberating about taking Hetherington with him to Liberia, he reviewed his work and found his photographs “disarmingly intimate,” he said, “different from anything I’d seen shot in the region before.” And once they were in the country, he saw a certain utility in the very slowness of the old-fashioned cameras, which put Hetherington on a slightly different plane during a firefight. “The fact that you had to slow down and look for the moment meant that he got these amazing pictures,” he said. Among them was one taken before the assault on Monrovia of a woman tenderly bidding farewell to her rebel lover, a photo that a typical war photographer would not have taken and which later would attract attention to Hetherington’s Liberia work. In its stark, almost formal simplicity, the photo was a poignant reminder of the personal impact of war.

Unpredictable violence and formal photography may seem worlds apart but pairing the two made sense to Hetherington. There was a wide divide between a place like Liberia, where life was so challenging for everyone, and the comparatively cushy world of the West, and he was determined to find a connection that others would recognize. So began the career of an inquisitive artist, propelled forward to the front lines of war by demons he never described, to illuminate the darkest corners of the world.

Because Hetherington’s career photographing wars began in Liberia that summer in 2003, Junger returned there in 2011 to interview people who had known him. At the start of his videotape Black Diamond sits in the dappled light of a beach cabana near Monrovia, apparently unaware that the camera is rolling. She pats her hair to make sure everything is in place, runs one hand across her face to smooth her makeup, and waits for the interview to start. She looks beautiful, framed by a backdrop of breaking waves, her large, expressive eyes and easy smile giving no hint of her infamous history as a war rebel. As soon as Junger begins his interview, Black Diamond tells him she does not want to talk about the past. She was now enrolled in school, and the whispers and stares that had followed her everywhere after the war had largely subsided. She lived in a house with small children who called her Aunt Diamond. But when Junger asks how she had met Hetherington, she is quickly transported seven summers back, to June 2003. It was near the climax of Liberia’s second civil war, a period of violence climaxing more than a decade of intermittent fighting. By that point in the war Black Diamond stood out in the rebel crowd. In one of the photos Hetherington took of her she wears a long, stained T-shirt and jeans, indicating that she’d had little time to prepare as she ran out the door that morning. In others she is well dressed: she wears a long, animal-print coat, or a red tube top and matching beret and wristwatch, with gold earrings, necklaces, and bracelets. In every photo she carries an AK.