Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Arena Sport

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

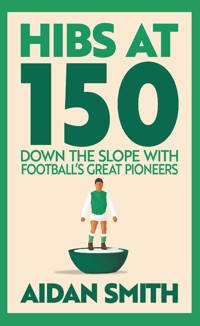

Celebrate 150 years of Hibs. Charting the highs, lows and many misadventures of Hibernian FC, and featuring countless characters, from George Best to John McGinn via the Famous Five and the side that became world champions, this is the ultimate celebration of the beloved Edinburgh sporting institution. It sweeps from the founding of the club in 1875 to the triumphs and tribulations of the 21st century. In 150 bitesize helpings, the story of Hibs is served up in delicious fashion. Who could forget the pass of the millennium or the swoon-inducing swagger of sixties heartthrob Peter Marinello? And who wouldn't recoil at the memory of the wine bar empire entwined in the club's darkest hour? Written by a lifelong Hibee, Hibs at 150 bridges the generations and peels back the layers of a century and half of Hibsteria.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 508

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Aidan Smith is the author of four previous books: Heartfelt, about a Hibby (himself) who turns Jambo; Union Jock, the same trick at international level played out across Hadrian’s Wall; Persevered, how Hibs stopped Hibsing it and finally won the Scottish Cup; and Bring Me the Sports Jacket of Arthur Montford, a celebration of what makes Scottish football special. As a journalist he’s won nine times at the Scottish Press Awards. He lives in Edinburgh with his wife and four children.

HIBS AT 150

DOWN THE SLOPE WITHFOOTBALL’S GREAT PIONEERS

AIDAN SMITH

For Sadie

First published in 2025 by

Arena, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright © Aidan Smith 2025

ISBN 978 1 78885 859 5

The right of Aidan Smith to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Typeset by Initial Typesetting Services, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by MBM Print SCS Ltd, Glasgow

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1. Foul Dens of Vice and Disease Unparalleled in Infamy

2. First Day at ‘Eebernians’: Sauzée Brought Fine Wine

3. Tarzan, Carmen, Billy the Kid, Sex Magick

4. Uniquely Green and White, in Subbuteo and Everywhere

5. Three Parts Harry Houdini, One Part Kim Kardashian

6. The Joy of Six–Six: Scotland’s Greatest-ever League Game

7. The World’s Third Oldest Cup Is Hibs’ For Ever

8. Bobby Johnstone, Bobby Combe, Bobby Smith, Bobby’s Bookshop

9. Join the Happy Crowd behind the Green Door

10. He Dropped Depth Charges in WW2 and Continued in Peacetime

11. Hibs Accused of Cheating, Private Detective Tries to Prove It

12. The Bad Girls Who Liked Bad Boys, Even the Good Girls Who Liked Bad Boys

13. Great Tourists, Unperturbed by Dark Skies or Dark-skinned Opponents

14. Choose the Belter against St Mirren, Choose the Bomb vs Kilmarnock

15. Six Old Pennies and Ladies Are Free to See the Champs of the World

16. The Goodfellas Bar Scene: With Hibs as 11 Waiters, Hearts as 11 Joe Pescis

17. ‘If We Passed Sideways Three Times, Eddie Turnbull Hauled Us Off’

18. The Pass of the Millennium: So What If We Lost 6–1?

19. Custard Pie Malarkey, Stepladder Mishap, Runaway Beds and Pianos

20. It’s Time to Say Sorry to Dundee, and Dumbarton

21. First to Wear the Green

22. Gothenburg? Fergie? You’re Welcome, Aberdeen

23. Invoking the Spirit of Mungo Park, without the Spear-chucking Natives

24. Were Hibs, Missing the Joke, First to Go Woke?

25. Homburg Hat, Frocked Coat, Striped Trousers . . . A Circus Showman

26. Don’t Other Teams ‘Hibs It’ Too?

27. ‘I Bought that Sheepskin Coat for Easter Road in Winter’

28. ‘None More Fascinating in a Football Arena’

29. It Was As If the H Bomb Had Been Dropped on Arthur’s Seat

30. ‘Glory, Glory to the Hibees’ is the A-side and It Presaged Rap

31. All His Brains Were in His Heid

32. ‘They’d Shout “Get Off!” at Me in the Warm-up’

33. It Looks Great from the Top of John Lewis, a Plane over the Forth

34. Hibs Immortalise Adidas Trainers, Sunak Kills Them Off

35. Scotland’s Greatest Musician Was Buried in His Hibs Tie

36. What Have We Got against Elvis?

37. Off to See the Wizard

38. Footballers Couldn’t Be Even Slightly Receding or Vaguely Bandy-legged

39. Tony Blackburn Mispronounces ‘Marinello’

40. Swooning and Squealing at Every Swerve and Sway

41. ‘Everything Tom Cruise Knows about Hibs He Learned from Me’

42. We Don’t Need No Stinkin’ Badges

43. The Unpeeling of the Onion

44. Bob Crampsey Called Us Silky and I Blushed

45. When We Thought Big Like Hitler

46. The Real Jim Herriot Came from Larkhall, Home to Alsatians Called Rebel

47. Was Prince Philip in Pat Stanton’s Pub, Chatting to Jimmy Boyle?

48. Three Handles: The First Draft of a Two Ronnies Gag

49. ‘Folks, Just Look at This Result . . . Hibs 8 Rangers 1’

50. When We Called Tynecastle Home

51. ‘I Refused to Stick It Up to Hibs for Getting Rid of Me’

52. A War Relic, Like Air Raid Sirens and Shortages of Nylon Stockings

53. How Hibs Killed the Best Panto Gags Stone Dead

54. The Brave Men Who Tried to Stop Them Painting the Town Maroon

55. Beckenbauer Invented the Role and Licensed It to Sloop

56. Charge Down the Slope, Trap the Opposition in Yonder Valley

57. Seeing the Light about the European Cup, Part 1

58. The Groundsman Mumbling from a Hut . . . Then Came Radio Hibs

59. The Forgotten Five Who Played Just Once

60. ‘There Was Such a Crush My Chocolate Bars Melted’

61. Utterly Featureless, Painfully Weak

62. ‘I Carried into Football What I’d Learned in Ballet’

63. Jambo Heads Swivel Through 360 Degrees in Shock

64. Intrepidly Prodded Forward, Right Foot Curled in Slightly

65. The Whimsical Philosopher

66. Seeing the Light about the European Cup, Part 2

67. Was the Future King’s Kink (Alleged) Inspired by Turnbull’s Tornadoes?

68. Fined for Bunking Off from Ayr Utd to Watch Hibs

69. Hibs as Art, by Muriel Spark’s Portrait Painter

70. There Was Us Lot and then This Other Guy, a God

71. Ramping Up the Bridge of Doom’s Mythology

72. ‘He Bestrode Hampden as Heroically as Any Man’

73. Revealed: The Greatest-ever Hibs Haircut

74. Is It a Hibs Thing to Sometimes Want Your Team to Lose?

75. Lawrie Reilly: ‘I Was Born in a Green Jersey’

76. ‘Without Tom Hart, Hibs Would Have Been Inconsequential’

77. A Whiff of Gorgeous George’s Genius

78. Not a Goalie Centre of Excellence, Not a Boot Hill Either

79. Tony Higgins, His Thighs and Football’s Hays Code

80. The Ticket Insisted: ‘This Portion Must Be Retained’. I Still Have It

81. Picked Up the Ball, Ran across the Copacabana with It

82. Scored Five, Booed by His Own Fans

83. Winter’s Diabolic Unless You Have a Blanket on the Ground

84. Grab Your Ankles and Kiss Your Ass Goodbye

85. Hibs Were Emerald, Hearts Ruby, Together: Diamond?

86. Greetin’ Faced, Couldnae Run, but oh the Vision!

87. Popjoys, Bloomers, Biancos . . . the Hibee Pub Crawl from Hell

88. ‘I Nicked Some Piping to Stick It in the Car Exhaust’

89. The Smallest, Skinniest, Most Talented and Bravest

90. ‘Arthur Duncan Very Nearly Started a War’

91. Back from the Wilderness, Back from the Dead

92. ‘The Green Jerseys Will Play Again’

93. Watching in String Vests, Jambos Saw Hibs Score Four

94. ‘If You Want Entertainment, Go to the Cinema’

95. It Was ‘Bend It Like Hammy’ First

96. Pals Talked into His Right Ear, Assuming He Was Half-deaf from the Abuse

97. ‘How the Hell Did We Manage to Sign Him?’

98. ‘We Watched Enchanted Hibs Supporters Cheering their Team’

99. ‘The Team Meal Was Chicken Basically Runnin’ Aboot’ 265

100. The Directors Peed in a Champagne Bucket

101. Like Suburbanites Wanting to Be First with Hot Tubs

102. Joe Baker’s White Boots

103. Brexit Means Brexit and Schaedler Means Schaedler

104. Relegation, Good for the Soul

105. ‘A Game Aflame with Antagonisms’

106. You Too Can Have a Body Like Mine

107. ‘They Called Me Trotsky and a Wee Commie Bastard’

108. The Daddy Daycare Boss of the Sugar-high Hibs

109. The German Ref Was Beaten Up, Ditto the Leith Police

110. Tynecastle Was an Ashtray

111. He Could Play Keepy-uppy with a Soap Bubble

112. ‘I Visited the Players in their Bath and Apologised’

113. In the Interests of Balance, the Time We Lost 7–0

114. ‘This Is Sheer Football Delight!’

115. The Other Time We Lost 7–0

116. Coulda Been a Contender, Shoulda Been a Hibee

117. The Secret Code Exclusive to Absolutely No One

118. Penalty Kicks, Such a Contrived, Confected Ceremony

119. Don’t Mention the War

120. Mickey Weir’s Angels with Dirty Faces Moment

121. Better than Matthews, Better than Finney

122. The Greatest Hibby Who Never Played

123. ‘I Always Kick Peter’s Headstone, Five Good Dunts’

124. When Hibs Became ‘Hybernia’, Disrupting the Biafran War

125. Back from the Concentration Camp, Eager for a Game

126. Hibs Reject Beats Black Power, Becomes World’s Fastest Man

127. In Bed with a Dolly Bird across His Chest, Swigging Champagne

128. Everybody Loves Sunshine

129. Ah! Ah! Ah! Ah! Comin’ Alive!

130. The F-word (Flair, Of Course)

131. He Died of a Broken Heart

132. Gone in 150 Seconds

133. ‘Did I Have a High Opinion of Myself? Of Course’

134. Did a Hibee Create the Monster Beckham?

135. The Scoreboard Was a ‘Son et Gloomiere’ Display

136. Traumatised by the Three-headed Monster

137. ’Mon the Cabbage!

138. Up Periscope to Torpedo the Champions League Supremacists

139. Like Smashing through Ice for a Penguin Dinner

140. A Traditional Scottish Sponge Cake

141. Scottish Cup Final, 2012 (Aagh!)

142. A Dream God, Mythical and Smithical

143. Can You Play Another Way? Stop This Bunker-busting?

144. The Prototype Heavy Lifter, Discovered by Jimmy Shand

145. The Trainspotting Team Had their Own Exclusive-use Station

146. Wronged Woman Gets Revenge, Helps Save Hibs

147. Can Anyone Here Tonight Play Centre-forward?

148. You’ll Never Guess My Second Team

149. He Shoots from Inside a Crowded Box, from the Roof of the Wild West Saloon

150. To Be Continued . . .

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

WHILE THE bulk of this book draws on my own experiences as a Hibs supporter – and rather less as a match-day reporter in the Easter Road press box where I would be told off for the occasional partisan yelp – I am grateful to the authors of Hibs histories going back beyond my fandom, including John Campbell, Alan Lugton, John R. Mackay and Tom Wright. A big shout out, too, to the purple prose-smiths of that press box from a more lyrical era of sportswriting whose work is preserved in the British Newspaper Archive.

At Birlinn, thanks to Paul Smith and Andrew Simmons for their advice, encouragement and the belief I could climb that sloping pitch and reach 150 chapters, and to Ian Greensill for his usual masterful copyediting.

Most of all, thanks to my team at home: wife Lucy and the children, Archie, Stella, Sadie and Hector, for cheering from the sidelines even when I got stuck on 97 chapters and there seemed nothing more to say about Hibs. On holiday in France in the summer, passing through Paris, passing the umpteenth kid in the colours of the newly crowned champions of Europe, Hec quipped from the back of the car: ‘We know a team who were made 150 years ago. PSG were only made last Tuesday.’

INTRODUCTION

ON CHRISTMAS Day 1875, Hibernian played their very first game of association football. Remarkably, they’ve made it to the sesquicentennial. ‘Put that in your pipe and smoke it!’ as we used to say, back in those nicotine-clogged days before the Clean Air Act. Put sesquicentennial in the title of this book? Well, I thought about it. The reaction, I’m sure, would have been: ‘Ah, how very Hibs.’

I say remarkably because along the way, while on the – cliché alert – journey, there have been bumps in the road as well as a slope on the pitch. In 1891 they went kaput and a century later it almost happened again. But they’re still around, entertaining fans like me, occasionally exciting, sometimes enraging, invariably ageing.

How, though, in marking those 150 years, to best describe the club to the unknowing? What to include as essential in the starter pack for those from Bogotá and Basildon who can’t stop replaying clips of ‘Sunshine on Leith’ on YouTube and X and are curious about what else the Hibees might have going for them?

I’ve tried to come up with a few things which could enlighten. Great teams, great players, great triumphs. Also, because this isn’t a hagiography or even a Hibby-ography, great humiliations, great disasters, great moments of unintentional comedy.

But I feel I’ve only scratched the surface. There’s this super-gizmo called the Large Hadron Collider which smashes subatomic particles into each other and from the resulting nuclear debris might be able to unlock some of the mysteries of the universe. Yes, fine, whoopee, but could it answer this question: ‘Why are Hibs Hibs?’ I reckon that would jigger the mechanics, reducing the LHC to a wheezing, clanking heap.

This is not a Hibby-ography and nor is it a complete century-and-a-half narrative. There are books out there which tell the whole story or major on key chunks of it and they do their jobs well. My father, among other things, was a playwright. His best-loved play properly got going when the central character was accused of peddling ‘too selective a view of history’. By all means, accuse me of this. Perhaps I’ve missed the moment when you and Hibs properly got going, your most cherished era. Sorry about that.

Me and Hibs properly got going in 1967. At first, evenhandedly, I saw as much of Hearts as I did the Hibees, with ‘lift-overs’ at both places. Then Dad asked if I wanted to choose. Would it be green or maroon? A few factors influenced my decision – among them the alluring length of Peter Marinello’s hair and the unalluring pong of Gorgie’s breweries – but colour definitely came into it.

In Sunday school: ‘There is a green hill far away . . .’ On TV variety shows, Tom Jones: ‘It’s good to touch the green, green grass of home . . .’ Meaning it most sincerely, Hughie Green. From America, escape-the-rat-race sitcom Green Acres. Frankenstein. Green Shield Stamps. On tins of peas: the Jolly Green Giant. John Buchan’s Greenmantle. In comic books: Green Lantern, The Incredible Hulk. Cluedo’s murderous minister the Reverend Green. For a boy in the late 1960s there was plenty of green around, much more than there was maroon.

This is personal and there’s quite a lot in the book about my early fandom. That phase ran from Easter Road initiation to the last game in the old 18-team First Division. I was, as my O-grade and Higher results will bear out, hopelessly devoted. Jotters were nicked from school to record Hibs’ progress with a multi-shaded jumbo pen in the kind of obsessional spidery-scrawl detail that would have triggered intervention by an educational psychologist, if there had been any of them around. But hopefully he or she would have concluded: ‘Regardless, this boy is having the time of his life with new discoveries and excitements every week.’ I entered the world of work bang on the start of the Premier League. Both life and football got more serious after that. That must have been when I learned what ‘cynical’ meant, possibly not being able to spell it before.

The Premier League was Hibs-driven. Lots of things in football have been Hibs-initiated and Hibs-inspired and they’re all here, along with others presented for the first time as further evidence, and to seal the deal, of what the old song says: ‘There’s not a team like the Edinburgh Hibees . . .’

Yes, I make grand claims. Yes, I occasionally get a bit carried away. Sesquicentennials, I find, have a habit of doing that. Pretentious, moi? Un fan de ‘Eebernians’, as Franck Sauzée would say? Mais oui! Now maybe this is a futile hope, given how tribal the game is now and how turnabouts are gone for good, but I’d like to think that fans of other clubs could get something from all of this. Dumbarton supporters are directed to chapters 11 and 20. Rangers supporters can have a chuckle at our expense in chapters 18 and 19 (but must be prepared to laugh at themselves as well). Jambos: you turn up a lot.

I began the book as Hibs were deep in the mire of their worst run of results for 40 years with yet another manager – and this time a Scottish Cup godhead in ‘Sir’ David Gray – seemingly set for the chop. Over and above that, football generally had been boring me for a while. At elite level: always overhyped, invariably underwhelming. At Scottish level: mandatory four-Old-Firm-games chokehold, vain efforts to catch up with the elites with inferior technology and passing rondos which come to a quick and dismal end.

But delving into the history of my club – disappearing down rabbit holes to resurface much later with flickering goals from long-lost Muirton and folkloric Cathkin and newspaper reportage in urgent yet poetic language that modern accounts have lost – some of the old excitements have returned. And out on the pitch the team’s form has improved to such an extent that, as I write, Hibs are venturing out across the continent again, 70 years after they pioneered European football. I may have to get my kids to nick more jotters and find that jumbo pen . . .

1

FOUL DENS OF VICE AND DISEASE UNPARALLELED IN INFAMY

THEY COULD have concentrated on being a debating society. Majored on the activities of the choral union. Thrown themselves into the drama club or the minstrel troupe or the accordion band. Or simply hung around the smoking room most of the time, occasionally rousing themselves for a game of skittles, dominoes or draughts. But oh no. The Catholic Young Men’s Society of St Patrick’s Church in Edinburgh just had to go and play football, become Hibs and for 150 years drive successive generations to distraction, despair and – just every once in a while, let’s not get too carried away – delirium.

Edward Hannan was a priest from Limerick who came to Scotland’s capital for a holiday, peered at the suppurating slums of the area of the Old Town known as Little Ireland and declared: ‘There’s work to be done here.’ So he stayed and in 1865 opened a branch of the CYMS in the Cowgate offering a wide range of improving pastimes for young men of the Irish immigrant population who’d had such difficulty integrating while trying to survive some of the worst living conditions in Europe.

Before long, new and bigger premises were needed. These would be St Mary’s Street Halls. Edinburgh’s lord provost laid the foundation stone, expressing the fond hope for a fillip to the fortunes of a community blighted by ‘foul dens of vice and disease unparalleled in infamy and disgust’. And St Mary’s would become Hibs HQ, just as soon as Michael Whelahan came up with the spiffing idea for association football as a means of Little Ireland planting its own foundation stone for acceptance by the wider city.

Whelahan’s flight to Edinburgh from Ireland had been more desperate: eviction, journey by foot from Glasgow, the death of a baby on the way. A member of the CYMS, and aged 21 in 1875, Whelahan happened by the Meadows in the spring of that year and was dazzled by what he saw. Rudimentary, near prehistoric football. Multiple games going off simultaneously. Random team sizes and pitch dimensions. Balls whizzing hither and yon. Slightly comical attire. Continuing into semi-darkness. Long-winded arguments and much-winded personnel. Charge and barge. Indeed, it was not unlike the football played on this expanse of green 150 years later by Edinburgh’s undergraduate community.

Whelahan relayed his excitement back to Canon Hannan. Football might not be able to wholly eradicate vice and disease and infamy and disgust. Indeed it has never got rid of the latter two in all this time and could be said to require, and benefit from, albeit to satisfy our perverted cravings, regular dousings of both. But football could at least provide the Irish émigrés with a purpose, a means of expression and a role in Edinburgh life.

Whelahan would be the first captain. (And a century later, his great, great, great grandnephew Pat Stanton would fulfil the role most splendidly.) He also came up with the name – Hibernians, from Hibernia, which was what the Romans called Ireland. Everything was set fair for the first game. Except . . . ‘the Association was formed for Scotchmen’. The curt response from the SFA to Hibs’ application to join was hammered home with the warning to existing member clubs not to fraternise with the ragamuffin outfit. Thankfully, the players of the other Edinburgh teams were much more welcoming. They petitioned the beaks who eventually relented and on Christmas Day the Hibees, amid much nervous excitement over how the upcoming hour and a bit would pan out, never mind the next 150 years, made their entrance in the world.

2

FIRST DAY AT ‘EEBERNIANS’: SAUZÉE BROUGHT FINE WINE

UP UNTIL 1999, a Hibs fan’s favourite Frenchman would have emerged from a five-way face-off involving the boy Baudelaire, the boy Renoir, Monet, Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre.

No, I’m kidding. The actual aspirants were Jacques Cousteau, Inspector Clouseau, the director of cinematography on the Emmanuelle films and the two metal-masked dudes out of Daft Punk.

Then on 20 February of that year, in a moment which surely deserved an addendum in at least a few of the histories being readied for the end of the millennium, an ageing French football aristocrat strode on to the pitch at Brockville.

Now, with the ground having a Gallic-sounding name, pronounced with the correct second-syllable inflection, this 33-cap Les Bleus redoubtable could very well have still been in his native land, in a semi-obscure rustic outpost, perhaps for an early rounds cup tie or an exhibition match. This might have been Brockville-sur-la-mer or Baroque-ville, mais non?

Plain old Falkirk, nowhere else. Franck Gaston Henri Sauzée, no one else. Champions League winner, serious continental soccer royalty. Tied equal with George Best, the most implausible, preposterous debut in Hibee history and, way out on its own, the most merveilleux. The fans probably thought they’d overdone the Cointreau, the Pernod, the Kronenbourg and yes, the absinthe, witnessing the first of many back heels from the midfield, and if they couldn’t quite believe it, then neither could Sauzée’s new team-mates at, as he would say, ‘Eebernians’.

‘This was Brockville,’ said Stuart Lovell, reminding himself. ‘Freezing cold dressing room. Condensation gushing down the walls. I’m sorry, but an absolute dump. And yet sitting next to me was Franck bloody Sauzée . . .’

‘Surreal,’ added Stevie Crawford, possibly unaware of the French origins of a term these days overused by sportsmen but in this instance completely justified. ‘We thought him signing for us was a wind-up. Hibs at the time, don’t forget, had been relegated. Training was the usual, any available patch of green, and we were like: “He’s not coming to this.” Then suddenly there he was and he’d brought along a smashing case of wine. Plastic glasses were found and he invited us to toast the day. He said: “I’m here with you my friends and I want us to do well.” That was pure class, pure Franck class, which was how he was all of the time.’

Along with the wine, Sauzée had a range of passes to be savoured. ‘He saw everything before it happened,’ added Crawford, which rather makes you wonder, after Brockville, what advance notice of Boghead had been like in the mind. But amid such modest surroundings the fans saw no need to qualify their approval. They nicknamed him ‘Le God’. With his dainty feet and a shot like the classic Napoleonic 12-pounder cannon, he led Hibs back to the big time, to cup finals and Europe. He is enshrined in Leith legend, not least for being part of a select band including wartime guest right-half Matt Busby who never lost an Edinburgh derby – and for two goals against Hearts which brought his disciples to orgasm without the need for any heavy petting from Jane Birkin, Françoise Hardy or Brigitte Bardot.

The first came in the Millennium Derby and just as memorable as the ferocity of the strike was his celebratory yomp the length of Tynecastle to cavort with the exploding away end.

The second at Easter Road cost him his front teeth. How did he hang in the air for so long? How did he stay laser-focused on the ball’s flight when he must have known that collision with the back of a thick Jambo skull was inevitable? Because he’s Le God. Famously, Willie Henderson’s contact lens was retrieved from the pitch by Tommy Gemmell. Every Hibby hopes Sauzée’s gnashers are still in the Dunbar End penalty box, undisturbed by seeder or mower, mementoes of a wonderful, 22 month-long acte de théâtre.1

1 Does not include his short, unhappy stint as manager, though he never lost a derby then either.

3

TARZAN, CARMEN, BILLY THE KID, SEX MAGICK

IT WASN’T just about Hibs in 1875. Blackburn Rovers were formed, Birmingham City too. And the first game of college football – gridiron – was staged in America along with the first game of indoor ice hockey in Canada. D.W. Griffith, a towering figure in early Hollywood, was born, along with Carl Jung, a towering figure in psychology. Oh and Aleister Crowley, a towering figure in sex magick where there’s a ritual called eroto-comatose lucidity: lots of arousal, bags of stimulation but stopping well short of actual orgasm. Hmm, how very Hibs.

Maurice ‘Bolero’ Ravel arrived in the world in 1875, as did boxing’s ‘great white hope’ James J. Jeffries who would almost masochistically absorb incredible punishment (Hibs-esque) then contrive a stunning triumph (not so much). Then there were these men of letters, creators of men of action: John Buchan and the two Edgars, Wallace and Rice Burroughs.

Also that year, the telephone was invented. Because in early fandom I soaked up everything about Hibs, memorising entire match programmes like I was in the dentist’s waiting room about to undergo root canal treatment and that was all there was to read, or I was a hostage chained to a radiator in some terrorist hellhole and that was all there was to read, I will probably end up quietly mouthing over and over the number to call the stadium, unfailingly printed on page two, during my deathbed delirium: ‘Abbeyhill 2159 . . . Abbeyhill 2159 . . .’

Another important invention: milk chocolate. The opera Carmen was composed, and also ‘I’ll Take You Home Again, Kathleen’. The largest locust swarm ever recorded turned the sky black over the Rocky Mountains, Billy the Kid was arrested for the first time (for stealing a basket of laundry) and Captain Matthew Webb became the first person to swim the English Channel.

Then there was Jeanne Calment, born in Arles, France in 1875, the oldest person who ever lived, seeing out of la porte 20 of her country’s presidents. She died on 4 August 1997, aged 122. Scotland’s back pages that day were all about a Hibs victory over Celtic, inspired by Chic Charnley.

Books published included A Gentleman’s Guide to Etiquette which advised: ‘If you have travelled do not be constantly speaking of your journeyings. Nothing is more tiresome than a man who commences phrases with ‘When I was in Paris . . .’ or ‘In Italy I saw . . .’ Wise words, although there are exceptions, such as your team being European Cup trailblazers (ch. 57) or the important evangelical work of a tour of Brazil to, ahem, educate the natives about flair-filled futebol (ch. 81).

Among the notable deaths was that of Georges Bizet, the Carmen guy, who went to his grave with the critics’ condemnation of his masterwork still ringing in his ears. A performance on the day of his funeral, however, had them all singing his praises. Opera, then, can be said to be not unlike football, with both provoking fickle reactions (cheer today, gone tomorrow). Also, are Hibs not the most operatic of football clubs? And Hans Christian Andersen died, prompting great mourning among lovers of fairy tales, the more morbid and grisly the better, much like a Scottish Cup quest lasting a whole 114 years.

Then there was the Public Health Act. By UK government decree there had to be proper sewage systems, basic jobby-wheeching. The law came into force in 1875, which was also when waste wizard Joseph Bazalgette completed his tunneling to future-proof London against a repeat of the Great Stink. So: a historic year for shite . . .

4

UNIQUELY GREEN AND WHITE, IN SUBBUTEO AND EVERYWHERE

EDINBURGH’S LITTLE Ireland had gathered to dance and sing and commemorate a famous son. The work of Daniel O’Connell, founding father of the modern Irish state, was done and his life was long over. But on the centenary of his birth, Hibs were just beginning with the official unveiling of club colours – white shirts with green trim.

O’Connell had been a huge figure, the champion of Catholic emancipation, whose oratory was of such passion that it brought tears to the eyes of a parliamentary reporter called Charles Dickens. The shirt spoke much more quietly of Ireland, doubtless because of the discrimination and sectarianism suffered in the Cowgate, with just a small harp on the breast.

The next version, taking the club through the remainder of the 1870s, saw more green. This was a hooped jersey, very much on trend in football back then, also for bathing, which enhanced a strapping chest and complemented the tumescent moustaches of the Victorian era.

The game was firmly in its knickerbocker years when knees were not permitted to be seen. It was a chaste time, but with no paparazzi there was zero threat of upbockering, the forerunner to upskirting, or of a gentleman displaying side-knee, preceding side-boob, and the snaps turning up in a scandal sheet.

Then, new century, new freedom. Out and proud and all green. The shade was bottle, changing to the emerald we know and love in the 1930s. And, shortly before the Second World War, following Arsenal and just in time for the dashing, debonair Gordon Smith, the white sleeves made their debut.

The collar – white – stayed rugby-style for the next 20 years. The permissive society hastened much unbuttoning, not just of social mores but football shirts. Along came the V-neck, ideally worn with the quiff popularised by Tony Curtis and all those wild and dangerous rock ’n’ rollers.

It was back to round collars for my all-time favourite. You never forget your first replica, this one purchased with paper-round wages from the Thornton’s sports emporium in Edinburgh’s Hanover Street. With neck and cuffs ringed in green – the vital flourishes – I attempted to dribble like Peter Marinello and defy gravity while waiting on a cross like Peter Cormack, even though that Mitre Mouldmaster, assuming the winger had succeeded in getting it airborne, was bound to hurt.

Turnbull’s Tornadoes kept the jersey classic, though mixed it up for Europe and all-green forays into Albania and old Yugoslavia. Then came regular tinkering, necessary from the marketing perspective but wholly unnecessary from the aesthetic one. There have been tight fits and baggy styles. Branding down the arms and bands across the chest. White body/green arms reversals. Ajax knock-offs, shirts for a beach holiday, striped sleeves from a clown show and those designs, since banished from memory, which were worn when performances resembled clown shows.

All told, something like 50 shades of green but fundamentally the colour has been constant which in the footballscape makes Hibs special. There are hundreds of red teams out there and thousands of blue teams. In the classic version of Subbuteo, the teensy plastic figurines referenced as No. 119 and sporting blue tops, white shorts and white socks could be Everton, Leicester City, Ipswich Town, Millwall, Chesterfield, Rochdale, Gillingham, Halifax Town, Queen of the South or Cowdenbeath. But No. 45 could only be Hibs.

5

THREE PARTS HARRY HOUDINI, ONE PART KIM KARDASHIAN

EVERY NOW and again a great escapologist will descend upon Edinburgh, render the populace open-mouthed and quaking with wonder at his uncanny ability to make a mockery of assorted attempts at capture – and then he’ll disappear. Aware that the city could not keep hold of him, literally and in every sense, the people are sad to see him leave, but happy to have known him for a while.

From 1904 when he first performed at the Gaiety Theatre in Leith until 1920 and his final appearance uptown at the Empire, that man was Harry Houdini. In all, the capital witnessed 50 show-stopping demonstrations of unshackling, extrication and tight spot-dodging.

From 8 August 2015 to almost the same day three years later, that man was John McGinn. He played 136 games for Hibs, scoring 18 goals. The number of times he emerged from a midfield ambush with the ball miraculously still at his feet is not recorded, but admirers know it to be huge.

America has the Kardashian clan and Scottish football has the McGinns. Stephen, Paul and John all had spells at Easter Road with John’s the most dazzling. I don’t think Kim Kardashian, the skincare tyrantess at the head of the late-stage capitalist nightmares, will mind me saying that to a not inconsiderable degree, her bahookie has been her fortune. Ditto McGinn.

Our game has produced some notable arses. When John Greig’s opponents moved in for a tackle, the Rangers captain would adopt the gait of music hall comedian Max Wall and the poor saps were bounced into the Ibrox enclosure. Kenny Dalglish scored many of his goals for Celtic, Liverpool and Scotland by starting out facing the wrong way then swivelling through 180 degrees, his bum acting as a force shield.

McGinn at Hibs was all-action and all-forward motion when other midfielders were crab-like. He was like the academy boy who skived or just plain ignored the instruction about passing laterally as a means of retaining possession (and sustaining a career). He retained it by charging towards goal and if ever he was halted, and there were times when it seemed he deliberately dallied for fun and mischief, then with the ball safe and under control he’d hunker into the sumo wrestler’s address position. There would be some vain attempt at dispossessing him before he’d continue on his merry, marauding way.

Film-maker Werner Herzog described Wayne Rooney as ‘half-bison, half-viper’. McGinn was all bison and beyond a game’s standard admission, tickets could have been sold for his amazing feats. Roll up, roll up! Gasp at the gluteus maximus which can never be fastened, fettered or foiled!

Houdini was variously billed as the Master Mystifier, the Handcuffs King and the ‘justly famous self-liberator’, escapologist not being a term used during his pomp. He cheerfully accepted challenges from sceptics and those determined to disprove his indestructibility and in 1913 the Edinburgh City Police Department dreamt up the ‘Insane Restraint Bag’ only for Houdini to leave the leather and canvas contraption in bits on the floor.

McGinn’s greatest showstopper came on Hibs’ greatest day, the 2016 Scottish Cup final. Early in the game he found himself surrounded. This was Rangers’ Insane Restraint Bag involving almost half their team. Hampden held its breath. The outcome would be psychologically crucial to one of these teams. Then, from the thicket of thrusting limbs, a head appeared. Meatball-shaped as McGinn himself would admit.

Now, there’s an act of Edinburgh escapology which predated Houdini and topped his stunts for being real. In 1861 an Old Town building collapsed with disastrous loss of life, but rescuers were encouraged to keep digging by the cries of a boy buried in the rubble: ‘Heave awa’, lads, I’m no’ deid yet!’ At Hampden the stupendous McGinn scrambling free with ball still tethered as Hibs justly famous self-liberator sent a similar message to his team-mates, inspiring them to victory.

6

THE JOY OF SIX–SIX: SCOTLAND’S GREATEST-EVER LEAGUE GAME

IT’S THE most exclusive of clubs. More select than a black card bolthole for the super-rich, with the conversation more rarefied than a cluster of the world’s greatest intellectuals debating epoch-making ideas. Applying for membership, seconders hold no sway. The key number here is six. No actually, it’s 12. Have you ever taken part in a 6–6 draw? That’s what will get you over to the other side of the velvet rope.

Hibs are part of this elite. Derek Riordan and Anthony Stokes reuniting need only nod to each other in airport terminals and dodgy pubs to confirm their extreme privilege, though maybe the correct greeting is 12 nods, which might be more appropriate for the special bond between them but could get a bit tedious in performance.

It was on 5 May 2010 that the Hibees journeyed through to Motherwell for an outcome that would be phantasmagorical. Is this the first time that Motherwell and phantasmagorical have appeared together in the same sentence? I reckon so. The league game had been brought forward 24 hours from the general election called by Prime Minister Gordon Brown. That was just as well for the politicians. Perhaps the fixture, due to be broadcast live on Sky, didn’t seem like an absolute must-see. But if it had gone ahead on polling day and you thought you’d have a quick look on TV before popping out to cast your vote, you might never have left the sofa. For the 1964 election Labour were so worried about the pull of a smelly, toothless rag-and-bone man that they had transmission of Steptoe and Son shifted. Forty-five years later the turnout threat would have been Colin Nish, Hibs’ hat-trick beanpole.

In the race for the last available European place, the match – on a pitch resembling waste-ground scrub – was expected to be tense, tight, unspectacular and most likely decided by a solitary goal. Just past the half-hour mark, five had been scored. It was 4–1 to Hibs and later it would be 6–2. I don’t know the personality of Motherwell and how the course of this game typifies it. I do know the personality of Hibs and just think: that’s us, a Hibsian set-up, script and conclusion. And as the goals kept coming, pubs showing Manchester City vs Tottenham Hotspur in other rooms found punters deserting these teams’ Champions League qualification scrap for the Fir Park orgy.

Guinness World Records confirm 6–6 as the highest score draw in football. It was achieved twice previously – in 1999 in Belgium by Racing Genk and Westerlo and the following year in Argentina by Gimnasia y Esgrima de La Plata and Club Atletico Colón. But the goals came easy in the former with five penalties awarded and four red cards, while in the latter there were two penalties and an own goal. So even though they drew on the night, Hibs and Motherwell won with election as joint life presidents of this most special of clubs. And if there is any quibble from the other members, then the trump card is Motherwell’s 93rd minute equaliser, an outrageous volley by Lukas Jutkiewicz from a laughable angle.

The best-ever Scottish Premiership goal? Some go further and rate the contest our best-ever. On its tenth anniversary, as we locked down for Covid-19 and wondered where the next game of football was going to come from, it was reshown on TV almost as an urgent salve to the country’s crumbling mental health.

Regular screenings should become a thing. And what about a book? I’ve got the perfect title: The Joy of Six-Six. The bearded man and the bangled woman from the original 1970s shagger manual could, through different copulating positions, interpret the goals for sensuous pencil illustrations. Regarding degree of difficulty, Jutkiewicz’s would be the equivalent of the one known as ‘The Piledriver’. Meanwhile the strike from Riordan who also bisected the posts from way out wide might rate as challenging as the ‘The Side Saddle’, perhaps even ‘The Standing 69’.

7

THE WORLD’S THIRD OLDEST CUP IS HIBS’ FOR EVER

THAT VERY first derby at the Meadows finished 1–0 to Hearts. And so began the grand municipal beef . . . After Nottingham Forest–Notts County it is the oldest, continuously played, full and frank exchange of views, football-wise, in the world. And the rivalry really took off for the citizenry early in 1878. On other pages I think about some of the Hibees from history, with the benefit of a time machine, that I‘d love to see play. The specific games I’d be programming into the temporal distortion engine would all be from this two-month period, all Hibs vs Hearts and indeed all the same tie.

This was the Edinburgh Football Association Cup, the world’s third oldest behind the Scottish Cup and the FA Cup, a first final for both clubs and surely another record: an incredible five matches would be required to settle matters. The final in its various iterations would career round the city like some comic-strip melee. You know: a dust cloud of protruding arms and legs, lurching between locations including Mayfield, Merchiston and Powburn, suggesting a nimby reaction from disgruntled local residents but exciting – and over-exciting – the still-evolving species known as the football follower.

Hibs finished the first match the stronger, also the first replay, confident they could win in extra-time, but the Hearts captain vetoed the additional half-hour. There had been fighting between the fans, so next time, admission was increased to try and price out the unruly element. But Irish navvies desperate to see the Hibees staged a break-in. They were denounced from the pulpit and in an effort to cool tempers the third replay was delayed. More suspenseful than a penny dreadful, the contest which began in the dead of winter was concluded with cherry blossom covering the ground. Hearts had the final say with a hotly disputed goal as their skipper was chased off the pitch and down the road by some badass Hibbies.

Their favourites would gain revenge the following season. And the next and the one after that. Three in a row and Hibs got to keep the cup, despite a last-gasp protest from Hearts that it was a local competition for local players and their opponents had fielded an outsider.

The niggle and needle were certainly enjoyed by local people. The crowds got bigger and more boisterous. Hibs moved around – from the Meadows to Powderhall to Mayfield and then Hibernian Park, a hefty clearance from what had yet to become Easter Road – and Hearts disbanded for a while. But with the Scottish League not yet begun, there was a lustful appetite for a regular fixture of the two teams slugging it out for city supremacy, so the cup was immediately replaced by the East of Scotland Shield.

Other sides from in and around Edinburgh participated, and occasionally won it, but this soon became a private affair and by the time I was hanging about the terraces (both grounds – see ch. 148) I loved the Shield. When we could only count on two derbies every year here was another. When neither club was winning anything, here was have-and-hold silverware. It didn’t matter that it was never paraded; that’s for this generation. Every kid gets a prize now. Every 6 Nations rugby game comes with a trophy attached. We just wanted, at the fag-end of each season, in the promise of a hot summer to come, to watch in our Simon shirts as Hibs and Hearts crashed into each other for a special offer bonus 90 minutes.

The Shield is still a thing but nowadays just for the youth sides. Who to blame for its downgrading? The Champions League, every single act of Gianni Infantino, football’s gigantism. But size isn’t everything, you know.

8

BOBBY JOHNSTONE, BOBBY COMBE, BOBBY SMITH, BOBBY’S BOOKSHOP

THE GENTLE descent of the street called Easter Road begins at a kilt shop. Hiring the plaid – trad or zazzily modern and bound to have hoary clan chiefs birling in their graves – is not essential. To the right is an old fire station, bright red doors, Toytownish, Trumptonesque (‘Pugh, Pugh, Barney McGrew . . .’) and to the left an imposing Gothic kirk. London Road Parish Church predated Hibs’ arrival by three years, which makes you wonder how many silent prayers were amassed (‘Pew, pew, Allan McGraw1 . . .’), and how heavy hung the hope, before 2016 when the blessed Scottish Cup was finally won. Its work done in its Church of Scotland incarnation, the doors closed a few months later and now the born-again congregate here under the banner of Christian Revivalism. (Not to be confused with the ‘happy clappers’ among the Hibs support, a term of non-endearment for the insanely optimistic who point-blank refuse to adopt the default disposition of epic go-on-impress-us grumpiness.)

Easter Road, the street, used to be soot-caked and forlorn. It’s still soot-caked but the shop names beneath the tenements read bold and optimistic now: Happy Bean, Écosse Éclair, Dazzelustrous. Further along: House of Lilith, Little Fitzroy, Cute But Deadly. These are obviously not ironmongers or haberdashers but nor are they charity shops. There’s vibrant young enterprise here – swagger with a bit of boho. And check out the graffiti on the wall over there: ‘Bagdad Bovver Boys vs Bengazi Uzi Krew.’ Well, are you going to be the brave schmuck who points out the missing aitches?

A Hibs supporter – he might be a schoolboy or someone who’s never been able to kick the habit in adulthood of racing buses down this thoroughfare – will tell you: ‘It is fitting, and at least to us perfectly apposite, that the local service is the No. 1.’2 The object of the race, of course, at least for adults, is to speed-walk to the next junction before the bus arrives, thereby guaranteeing a win in the upcoming game.

Easter Road’s sense of self, the belief that it’s no ordinary street, was further evident in the name chosen for its cinema. The Picturedrome opened in 1912, a year Hibs began with a 5–0 thrashing of Rangers. Scribes of the day hailed that result ‘one of the greatest surprises known to Scottish football’ though Rangers would conclude the season as champions. Hibs, back in their box, were back in 13th.

In 1912, D.W. Griffith was the pre-eminent name in movie-making but coming up fast on the outside, sirens wailing dementedly and tyres screeching, was Mack Sennett and his Keystone Cops. The Picturedrome is long gone, but if you look up at the rooftops, the curlicues from its grand frontage are still visible.

Now, I sense that some of you are yet to be convinced of Easter Road, present or past, as anything resembling exotic. Will Bobby’s Bookshop do this? It should. The branch here was like the others in Edinburgh and a comics cornucopia (Commando, DC and, before they killed the film-going experience, Marvel). While boys thrilled to vapour trails and splatter, girls coveted scraps of cloud-dwelling cherubs who these days would probably be fat-shamed. I bought my copies of Mad from this stupendous emporium, the mag’s baby-steps satire, all-American, enabling one-upmanship on schoolmates who’d never heard of Spiro Agnew, or who vainly speculated about him possibly having invented Spirograph. So, while Bobby Johnstone, Bobby Combe and Bobby Smith were all revered at Easter Road, the stadium, Bobby at his Bookshop just around the corner was supplying fun and occasional edification. At least my generation was reading something . . .

So anyway, where is that stadium? After The Edinburgh Honey Company turn right into Albion Road, a few hundred yards, bear left for Albion Place and . . . hunkered next to more tenements it looks faintly ridiculous: an out-of-proportion interloper, far too big for the space and as it looms large, strangely reminiscent of . . . this’ll probably sound odd: the giant tabby cat squatting on the GPO Tower in The Goodies.

1 1960s striker, nicknamed ‘Quick Draw’ when Westerns were still popular, featured in my first Hibs game, suffered for the cause through pain-killing jabs to help the team overcome semi-final strife, hirpled through later years, stood – as best he could – for Scottish Parliament.

2 The 1 service also calls in on bandit country (Gorgie).

9

JOIN THE HAPPY CROWD BEHIND THE GREEN DOOR

EYES ADJUSTED, let’s take a closer look, a voyage round my ground . . . Like Easter Road the street, Easter Road the stadium has a kirk, actually two as its closest neighbours, and similarly they’ve become surplus to Church of Scotland requirements. But they stay put, jammed together as in a defensive wall facing a free kick, and their continued presence in body if not in spirituals is a good thing. It’s important that the club, in their surroundings at least, have constants while players, managers, owners, systems and shirt designs blithely come and go.

Behind the kirks, St Mungo and Lockhart Memorial, is what used to be Norton Park, both a primary and a secondary school. Just imagine the amount of daydreaming that went on during lessons, with playtimes devoted to collecting players’ autographs.

It was harsh learning at Norton Park with former pupil chat-rooms remembering days when entire classes were lined up for the belt. Almost without exception the kids were moulded for industry, but Alex Cropley was one who went from classroom to changing room across the way. The school and the churches have been repurposed: a charity hub, a conference centre and what the website terms ‘green benefits’, something Cropley and Turnbull’s Tornadoes delivered in a different way just about every week.

These buildings are not going anywhere and neither is the graveyard across from the club shop, but after moving past what is now called the Famous Five Stand, newish housing pushes us southwards. These dwellings might be coveted by fans but sadly cannot have a view of the park although at times when those green benefits have been beyond Hibs, this must count as a blessing. The same could be said for the flats on the corner of Albion Place. Before the Famous Five Stand went up, the pitch lay out in front of them. And in 2025, ground redevelopment not always being matched by team redevelopment, the gable end issues this directive in big, dramatic lettering: ‘Sack the board!’

Continue south and you could easily end up in Lochend Park with its pond, a tranquil spot in spite of the erect dorsal fins, red bellies and psycho grimaces of the sticklebacks. As well as fishes here there used to be loaves. Nearby is the site of the old Smith’s Bakery which offered warm walls for kids’ wintertime huddles and the sweet aroma of freshly baked bread 24 hours a day, all year round.

We’ve strayed too far, we’ll miss kick-off. Heading back to the stadium up the other side, another former factory, also much loved, is discernible in fading paint on a red-brick wall: ‘James Dunbar’. This was the lemonade works which brewed Kola with a K, repelled the advances of Coca-Cola because it regarded the latter as inferior pop, and lives on in the ground. If you’re of a certain age, the away fans’ stand will always be the ‘Dunbar End’.

Nowadays, painters and sculptors exhibit in the premises and as the stands loom into view once more, there is art of a kind on every lamp post and utility box, which have become the canvases of visiting fans. Black-clad junior emissaries from Borussia Dortmund in Germany, Marseilles in France, Burgos in Spain and some skinheads from Italy’s Termoli have left stickers as calling cards which form into mosaics. The Hibby response includes ‘HFC’ in olde script as the letters appeared on the shirts of the 1902 Scottish Cup-winning team. Also this: ‘Kensell sells his farts in jars.’1

Now we’re back where we started, the north end which honours the club’s most famous sons, and the words of the eminent philosopher Shakin’ Stevens come to mind: ‘All I want to do is join the happy crowd behind the green door.’

But maybe not this green door, some feet below the image of Willie Ormond, for it reads: ‘Keep out – danger of death.’

1 Ben Kensell, the unloved CEO who left at the beginning of the sesquicentennial just as Hibs posted a £7.2 million loss.

10

HE DROPPED DEPTH CHARGES IN WW2 AND CONTINUED IN PEACETIME

HUGH McILVANNEY’S 1997 documentary The Football Men is acclaimed for telling the story of the coal town colossi of the game – Matt Busby, Bill Shankly and Jock Stein. It’s terrific but I probably prefer Bring Your Own Ball screened 24 years previously and for two reasons. One, I’m biased – it was made by my father who was able to interview the triumvirate when they were still alive. Two, his film featured another great manager who emerged from Scottish mining stock – Eddie Turnbull.

The Football Men borrowed footage from Bring Your Own Ball so the year after Dad died, I heard his voice from beyond the grave enquiring of each of his subjects: ‘Are you a disciplinarian?’

A bold question – fluffy in-house TV at clubs has allowed coaches to expect softballs now – but can I say, Faither, that in 1973 it was possibly superfluous? Parents were disciplinarians, so were schoolteachers and certainly football managers, not least Turnbull, and while I wish I could have seen him play for Hibs, it was thrilling to watch the team he managed and, later, fascinating to collect my own sound bites about his working practices.

‘He enlightened everyone,’ John Blackley told me. Alex Cropley said: ‘No disrespect to the guys that came before him but they were simply playing at it.’ Des Bremner: ‘A visionary.’ Roy Barry: ‘The best coach I ever had.’ And this from Ally MacLeod who already seemed to possess sufficient football intelligence: ‘I properly learned about the game from him.’

Alex Edwards was managed by both Turnbull and Stein. Who was best? ‘Eddie – he was a genius.’ Turnbull answered to Ned, although Edwards, who coined many of the Easter Road nicknames, had another one for the boss. ‘Remember Wacky Races? And Dick Dastardly’s dug and how it shoogled its shoulders when it laughed? To me Eddie was Muttley although obviously I never called him that to his face.’

Before the Famous Five – 202 goals in 487 games – he was Able Seaman Turnbull on the Atlantic Convoys during the Second World War. Journeys from Greenock to Murmansk were fraught with danger from Luftwaffe bombers and mountainous seas.

Aboard HMS Bulldog, Turnbull dropped the depth charges, which might fit as a description of his management style. Before underperforming Hibs for him, there was underperforming Aberdeen. ‘He came to sort us out,’ remembered Martin Buchan. ‘The club had been a holiday camp for older players from the Central Belt. In just two months he got rid of 17. One guy was sent away from training because he couldn’t take a corner. When he came out of the shower, Eddie was waiting for him. “The secretary’s got your wages,” he said. “I don’t want to see you again.”’

But those he liked and, who bought into his ideas, loved him. They included Arthur Graham, Davie Robb (‘Very hard but very fair; I always called him Mr Turnbull’), Bobby Clark (‘Ahead of his time, he had us high-pressing before the world knew about that’) and Ernie McGarr (‘Rugby gave him the idea for overlapping full-backs and we goalies went outfield in practice matches with the order: “Play starts with you so learn everyone’s role”’).

Stevie Murray admired his psychology: ‘Joe Harper and Jim Forrest both wanted to be centre-forward and wouldn’t pass to each other. He moved Jim out to the wing because he was fast but gave him the No. 9 shirt so he’d think he was centre-forward. I was devastated when Eddie left us for Hibs.’

So was Buchan who owed his career to Turnbull: ‘He walked us through situations in games until everything became second nature. Average players won Under-23 caps just through what they learned from him. When I left Aberdeen I could have gone to any team in the world and played in any system, thanks to the master.’

And then there was Harper, who emerged from the manager’s office with a black eye after failing to adequately explain why he’d been drunk in charge of a snow plough and would later follow Turnbull to Easter Road. He said: ‘I’d like to think I was the son he never had.’

Maybe none of the Hibees inherited by Turnbull went quite as far as that. Maybe in Leith, admiration came with a quibble about man management or lack thereof. Maybe that was the world starting to change with official recognition of ‘feelings’, for at the moment the Tornadoes began to reflect on the Ned experience, bosses were expected to be as adept at an arm round the shoulder as a boot up the arse. But maybe, too, Turnbull’s frustration was greater at Hibs because this team could, and should, have been the best in the land.

11

HIBS ACCUSED OF CHEATING, PRIVATE DETECTIVE TRIES TO PROVE IT

FOR A while, not quite 114 years although it felt like that long, many in Scottish football and nearly all Jambos were obsessed with 1902. They knew who sat on the British throne (Edward VII). The identity of the great and goateed Wild West soldier-showman still going strong (Buffalo Bill). The year’s whizzo inventions (vacuum cleaner, air conditioning, brassiere). The bloody conflict finally brought to a close (Boer War). This was the sort of stuff which was Wiki-sourced and flung at Hibs for lamentably failing to hoist the Scottish Cup in all that time. Until, after 114 years, they finally did.

But the club’s earlier triumph, the one on 12 February 1887, is the better story. Not just for being Hibs’ first in the competition, what would now be called a statement win, and the first time the trophy had been prized from the Wild West of Scotland, but a sensational sub-plot straight out of the ripsnorting adventures of Sherlock Holmes who made his debut in print that same year.

Hibs overcame five teams to reach the final including the sadly gone Durhamstown Rangers, Mossend Swifts and Third Lanark, back then still bearing the proud initials RV for Rifle Volunteers. There were some impressive scores, including six against Durhamstown, seven against Queen of the South Wanderers and another five put past the hapless custodian of some mob called Heart of Midlothian. Then in the semi-final they defeated Vale of Leven with Willie Groves (see ch. 28) notching his eighth and ninth goals of the competition.

Not so fast, said Vale, and not so legal either. They alleged skulduggery, lodging a complaint of professionalism against Hibs in what was still the amateur era for the Scottish game. And what Hibees historian Alan Lugton called ‘one of the most celebrated, controversial and bitter cases ever heard by the SFA’ began just two days before the final.

That’s proper stress, something which wouldn’t be countenanced by teams now. So close to a grand showpiece, they would want their only angst to concern haircut options and whether the big cardboard sign advertising telly transmission was being held the right way up.

The hearing was adjourned, resuming right after the victory over Dumbarton, when Hibs’ accusers produced what they hoped would be their trump card – the findings of a private detective.

Perhaps this gumshoe had been motivated to join this relatively new profession by Allan Pinkerton who’d set sail from Glasgow for America to found the sleuths agency bearing his name. In 1887, what would have been the extent of the Dumbarton man’s skill set? And the extent of his disguise? It’s probably as well that A Study in Scarlet didn’t ignite the Holmes phenomenon in time for his skulking around the mean streets of Leith, for appropriating Holmes’s deerstalker, cape, violin and intravenous drugging would probably have blown his cover.

As it was, Hibs did rumble him and hurriedly moved training away from Easter Road.