2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: eKitap Projesi

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

This book, re-edited and illustrated by e-kitap projesi and published again in ebook format. In this book, telling that Boyhood stories of the Most famous persons in the world, and so These 21 famous persons lay out from Christopher Colombus –The pre-founder of the America- to Otto von Bismarc.

For example: “When he was sixteen Napoleon and his best friend, a boy named Desmazis, were ordered to join the regiment of La Fère which was then quartered in the south of France. Napoleon was glad of this change which brought him nearer to his island home, and he also felt that he would now learn something of actual warfare. The two boys were taken to their regiment in charge of an officer who stayed with them from the time they left Paris until the carriage set them down at the garrison town. The regiment of La Fère was one of the best in the French army, and the boy immediately took a great liking to everything connected with it. He found the officers well educated and anxious to help him. He declared the blue uniform with red facings to be the most beautiful uniform in the world.

He had to work hard, still studying mathematics, chemistry, and the laws of fortification, mounting guard with the other subalterns, and looking after his own company of men. He seemed very young to be put in charge of grown soldiers, but his great ability had brought about this extraordinarily rapid promotion. He had a room in a boarding-house kept by an old maid, but took his meals at the Inn of the Three Pigeons. Now that he was an officer he began to be more interested in making a good appearance before people. He took dancing lessons and suddenly blossomed out into much popularity among the garrison. Older people could not help but see his great strength of character, and time and again it was predicted that he would rise high in the army.”

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 355

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

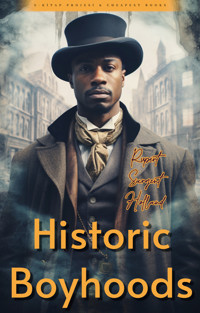

Historic Boyhoods

Rupert Sargent Holland

Author of “The Boy Scouts of Birch-Bark Island,”

“The Blue Heron’s Feather,” and “Peter Cotterell’s Treasure” etc.

Illustrated

ILLUSTRATED &

PUBLISHED BY

E-KİTAP PROJESİ & CHEAPEST BOOKS

www.cheapestboooks.com

www.facebook.com/EKitapProjesi

Copyright, 2014 by e-Kitap Projesi

Istanbul

Contact:

ISBN: 978-615-5564-02-4

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

About Author

Rupert Sargent Holland (1878-1952) was an American author. His works include: Historic Boyhoods (1909), The Boy Scouts of Birchbark Island (1911), The Boy Scouts of Snowshoe Lodge (1915) and King Arthur and The Knights of the Round Table. "A privateer was leaving Genoa on a certain June morning in 1461, and crowds of people had gathered on the quays to see the ship sail. Dark-hued men from the distant shores of Africa, clad in brilliant red and yellow and blue blouses or tunics and hose, with dozens of glittering gilded chains about their necks, and rings in their ears, jostled sun-browned sailors and merchants from the east, and the fairer-skinned men and women of the north."

* * * * *

Preface (About the Book)

HISTORIC BOYHOODS (1909)

This book, re-edited and illustrated by e-kitap projesi and published again in ebook format. In this book, telling that Boyhood stories of the Most famous persons in the world, and so These 21 famous persons lay out from Christopher Colombus –The pre-founder of the America- to Otto von Bismarc.

For example: “When he was sixteen Napoleon and his best friend, a boy named Desmazis, were ordered to join the regiment of La Fère which was then quartered in the south of France. Napoleon was glad of this change which brought him nearer to his island home, and he also felt that he would now learn something of actual warfare. The two boys were taken to their regiment in charge of an officer who stayed with them from the time they left Paris until the carriage set them down at the garrison town. The regiment of La Fère was one of the best in the French army, and the boy immediately took a great liking to everything connected with it. He found the officers well educated and anxious to help him. He declared the blue uniform with red facings to be the most beautiful uniform in the world.

He had to work hard, still studying mathematics, chemistry, and the laws of fortification, mounting guard with the other subalterns, and looking after his own company of men. He seemed very young to be put in charge of grown soldiers, but his great ability had brought about this extraordinarily rapid promotion. He had a room in a boarding-house kept by an old maid, but took his meals at the Inn of the Three Pigeons. Now that he was an officer he began to be more interested in making a good appearance before people. He took dancing lessons and suddenly blossomed out into much popularity among the garrison. Older people could not help but see his great strength of character, and time and again it was predicted that he would rise high in the army.”

Table of Contents

Historic Boyhoods {Illustrated}

About Author

Preface (About the Book)

Table of Contents

Chapter I

Christopher Columbus

Chapter II

Michael Angelo

Chapter III

Walter Raleigh

Chapter IV

Peter the Great

Chapter V

Frederick the Great

Chapter VI

George Washington

Chapter VII

Daniel Boone

Chapter VIII

John Paul Jones

Chapter IX

Mozart

Chapter X

Lafayette

Chapter XI

Horatio Nelson

Chapter XII

Robert Fulton

Chapter XIII

Andrew Jackson

Chapter XIV

Napoleon Bonaparte

Chapter XV

Walter Scott

Chapter XVI

James Fenimore Cooper

Chapter XVII

John Ericsson

Chapter XVIII

Garibaldi

Chapter XIX

Abraham Lincoln

Chapter XX

Chapter XXI

Otto von Bismarck

HISTORIC BOYHOODS

{Illustrated}

BY

RUPERT SARGENT HOLLAND

Author of “The Boy Scouts of Birch-Bark Island,”

“The Blue Heron’s Feather,” etc.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY

Murat Ukray {e-Kitap Projesi}

The Fleet of Columbus “Nearing America”

Chapter I

Christopher Columbus

The Boy of Genoa: 1446(?)-1506

A privateer was leaving Genoa on a certain June morning in 1461, and crowds of people had gathered on the quays to see the ship sail. Dark-hued men from the distant shores of Africa, clad in brilliant red and yellow and blue blouses or tunics and hose, with dozens of glittering gilded chains about their necks, and rings in their ears, jostled sun-browned sailors and merchants from the east, and the fairer-skinned men and women of the north.

Genoa was a great seaport in those days, one of the greatest ports of the known world, and her fleets sailed forth to trade with Spain and Portugal, France and England, and even with the countries to the north of Europe. The sea had made Genoa rich, had given fortunes to the nobles who lived in the great white marble palaces that shone in the sun, had placed her on an equal footing with that other great Italian sea city, Venice, with whom she was continually at war.

But all the ships that left her harbor were not trading vessels. Genoa the Superb had many enemies always on the alert to swoop down upon her trade. So she had to maintain a great war-fleet. In addition to this danger, the Mediterranean was then the home of roving pirates, ready to seize any vessel, without regard to its flag, which promised to yield them booty.

The life of a Genoese boy in those days was packed full of adventures. Most of the boys went to sea as soon as they were old enough to hold an oar or to pull a rope, and they had to be ready at any moment to drop the oar or rope and seize a sword or a pike to repel pirates or other enemies. There was always the chance of a sudden chase or a secret attack on a Christian boat by savage Mussulmen, and so bitter was the endless war of the two religions that in such cases the victors rarely spared the lives of the vanquished, or, if they did, sold them in port as slaves. Moreover the ships were frail, and the Mediterranean storms severe, and many barks that contrived to escape the pirates fell victims to the fury of head winds. The life of a Genoese sailor was about as dangerous a life as could well be imagined.

On this June morning a large privateer was to set sail from the port, and the families of the men and boys who were outward bound had come down to say good-bye. The centre of one little group was a boy about fifteen, strong and broad for his years, though not very tall, with warm olive skin, bright black eyes, and fair hair that fell to his ears. His name was Christopher Colombo, and he was going to sail with a relative called Colombo the Younger who commanded a ship in the service of Genoa.

The young Christopher had always loved to be upon the sea. Among the first sights that he remembered were glimpses of the Mediterranean in fair and stormy weather, the first tales he had heard were stories of strange adventures that had befallen sailors. His home had sprung from the waves, its glory had been drawn from the inland sea, the great chain of high mountains at its back cut it off from the land and the pursuits of other cities. Christopher thought of the sea by day, and dreamed of it by night, and was already planning when he grew up to go in search of some of those strange adventures the old bronzed mariners were so fond of describing.

The boy's mother and father kissed him good-bye, and his younger brothers and sister looked at him enviously as he left them with a wave of his hand and went on board the ship. The latter was very clumsy, according to our ideas. She rode high in the water, with a great deck at the stern set like a small house up in the air, and with a great bow that bore the figurehead of the patron saint of the sea, Saint Christopher. Her sails were hung flat against the masts and were painted in broad stripes of red and yellow. She was very magnificent to look upon, but not very seaworthy.

The marble of Genoa's palaces dropped astern. The ship was sailing south, and under favoring breezes soon lost sight of land. Constant watch was kept for other vessels; any that might appear was more apt to be an enemy than a friend, because Genoa was at war then with many rivals, chief among them Naples and Aragon. Ships had been sailing constantly of late from Genoa to prey upon the commerce of Naples, in revenge for what the Neapolitans had once done to Genoa.

Colombo the captain was fond of his young kinsman Christopher, and at the start of the voyage had him in his cabin and told him some of his plans. The captain said he had orders to sail to Tunis to capture the Spanish galley Fernandina. The galley was richly laden, and each sailor would have a large share of booty. The boy listened with sparkling eyes; this would be his first chance to have a hand in a fight at sea.

The winds of June were favoring, and Colombo's ship soon reached the island of San Pietro off Sardinia. Here the captain went ashore to try and learn news of the Fernandina. He found friendly merchants who had word from all the Mediterranean ports, and they told him that the galley was not alone, but accompanied by two other Spanish ships. Colombo was a born fighter, and this news did not frighten him. The more ships he might capture the greater would be his own share of glory and of prize money.

When the captain told his news to the sailors on his return from shore, there was great consternation. The men had no liking to attack two fighting ships besides the galley. At first they simply murmured among themselves, but the longer they discussed the desperate nature of the plan the more alarmed they grew. By the time that the ship was ready to sail southward from Sardinia they had determined to go no farther, and sent three of their leaders to speak to Colombo.

The captain was with Christopher studying a map of the Mediterranean when the men came before him. They told him that they positively refused to sail south and insisted that he put in at Marseilles for more ships and men. Colombo saw that he could not force them to sail farther, so, with what grace he could, he gave his consent to alter the course.

The men left the cabin, and after a few minutes' thought the captain spoke to the boy. "Christopher," said he, "bring me the great compass from its box near the helmsman's stand. Bring it secretly. The men should all be on the lower deck making ready to sail. Let no one see thee with it."

The boy left the cabin and climbed the ladder to the great poop-deck at the stern where the helmsman had a view far over the sea. He waited until no one was about, and then quickly took the compass from its box, and hiding it under the loose folds of his cloak, brought it to the captain. He placed it on the table. Then he fastened the door so that none might enter.

Colombo opened the compass-case, and drew a pot of paint and a brush toward him. The boy watched breathlessly while the captain painted over the marks of the compass with thick white paint, and then on top of that drew in new lines and figures in black. He was changing the compass completely.

When the work was done Christopher bore the case back to its box as secretly as he had taken it. Then Colombo went out to the sailors and gave them orders to spread sail. It was rapidly growing dark as they left the coast of Sardinia.

At sunrise, when Christopher came on deck to stand his watch, he knew that their ship must be off the city of Carthagena, although all the crew supposed they well on their way to Marseilles. Not long after, as they were drawing nearer to the shore, the lookout signaled a vessel. She was soon seen to be flying the flag of Naples. Fortunately this ship was alone at the time, and the sailors were not afraid to attack her.

Orders were quickly given to sail as close to her as possible, and preparations were made to board her. The other ship seemed no less eager to engage in battle, and in a very short time grappling-irons were thrown out and the ships were fastened close together. Then a fierce combat followed between the two crews as each in turn tried to scale the sides of the other vessel.

A sea-fight in the fifteenth century was fought hand to hand, each ship being like a fort from which small attacking parties rushed out to climb the other's battlements. When men met on the decks they used sword and pike and dagger just as they would have on shore. Fire was thrown from one ship into the rigging and sails of the other, and flames soon caught and greedily devoured the woodwork of the boats. It was wild work; the blazing sails, the broken cheers of the men, the fierce struggle over the two decks.

Christopher fought bravely whenever chance offered, but the captain kept him close to his hand to carry messages. It soon appeared that the enemy were the stronger, and they bore the Genoese back and back farther from their bulwarks and across their decks. As the enemy gained a foothold they held torches to everything that would burn, and soon Colombo's ship was wrapped in fire and the only choice seemed to be between surrender and jumping into the sea.

A burning rope fell from a mast and set fire to Christopher's cloak. He tore the cloak from him. He saw that the Neapolitans must win and he had no desire to be carried off to Naples as a prisoner. The flames were gaining fast as he leaped to the rail on the free side of the ship, and dove overboard. He came up free from the wreckage and found a long sweep-oar floating near him. With that support he struck out for the shore of Africa, only a short distance away. His first sea-fight had nearly proved his last.

Self-reliance was the corner-stone of this young mariner's character. He could take care of himself on whatever shore he was thrown. He landed on the beach of Carthagena and told the story of his adventures to the group of sailors who crowded about him on the sands. There is a strong sense of comradeship among seamen, and so, although none of the men who heard the boy's tale were from Genoa, they fitted him out with dry clothes and found enough money to keep him in food and shelter.

There he stayed for some time, waiting until some Genoese bark should put into port. Meanwhile he was very much interested in the stories the seafarers of all lands told to people who would listen to them. Again and again he heard mariners wondering whether there might not be a shorter passage to the rich Indies of the East than the long overland route through China. The question interested him, and he took to studying it with care.

One day an old sailor on the beach told him of his voyages in the western ocean, and how once his ship had come so close to the edge of the world that but for the miracle of a sudden change in the wind they must certainly have been carried over the side. The same bearded seaman told Christopher many other curious things; how he had himself seen beautiful pieces of carved wood, cut in some strange fashion, floating on the western sea, and had picked up one day a small boat which seemed to be made of the bark of a tree, but of a pattern none had ever seen before.

Then, and here his voice would sink and his eyes grow large with wonder, he told Christopher how men who were explorers were certain that somewhere in that unsailed western sea, just before one came to the edge, was an island rich in gold and gems and rare, delicious fruits, where men need never work if they chose to stay there, or if they came home might bring such treasures with them as would put to shame the richest princes of all Europe. It was said that there one caught fish already cooked, and that there people of great beauty lived, with dark red skins and wearing feathers in their hair.

"And is no one certain of this?" asked Christopher, his eyes wide with excitement. "Not even the men who have found the African coast and the isle of Flores?"

The old sailor shook his head. "Nay, nay, boy. The wonderful island lies so close to the world's edge that 'tis a perilous thing to try to find it."

"Still," said Christopher, "'twould be well worth the finding, and some time when I'm a man and can win a ship of my own I'm going to make the venture."

But the sailor shook his head. "Better leave the unknown sea to itself, lad," said he. "A whole skin is worth more to a man than all the gold of King Solomon's mines."

"Is it true," asked the boy after a time, "that there are terrible monsters in the Dark Sea?" That was the name given in those days to the ocean that stretched indefinitely to the west. "I've seen pictures of strange creatures on ships' maps, but never saw the like of any of them."

"No, nor would you be likely to, lad," said the sailor, "for such as see those monsters don't come back. But true they are. A great captain told me once that part of the Dark Sea was black as pitch, and that great birds flew over it looking for ships. You've heard of the giant Roc that flies through the air there, so strong that it can pick up the biggest ship that ever sailed in its beak, and carry it to the clouds? There it crushes ship and men in its talons, and drops men's limbs, armor, timber, all that's left, down to the Dark Sea monsters who wait to devour the wreckage in their huge jaws. Ugh, 'tis an ugly thought, and enough to keep any man safe this side the world."

"In some places fair, in some dark," mused Christopher. "It would be worth sailing out there to find which was the truth."

"Where would be the good of finding that if you never came back, boy?"

Christopher shrugged his shoulders. "Just for the fun of finding out, perhaps," he said.

A month later Christopher saw a galley flying the flag of Genoa enter the harbor. When the captain came on shore the boy went to him, and telling him who he was, asked for a chance to go as sailor back to Genoa. The captain knew the boy's father, Domenico Colombo, and gave Christopher a place on the galley. She was sailing north, homeward bound, and a few days later, having safely avoided all hostile ships and storms, the galley came into sight of the beautiful white city in its nest against the hills.

It was a happy day when the young sailor landed and surprised his father and mother by walking in upon them. News of Colombo's defeat by the ship of Naples had come to Genoa, and Christopher's family had given him up as lost.

But narrow as his escape on that voyage had been, such chances were part of the sailor's life in that age, and Christopher was quite ready to take his share of privation and danger with his mates. It was only by weathering such storms that he could ever hope to be put in charge of rich merchantmen or to command his own vessel in his city's defense. So he sailed again soon after, and in a year or two had come to know the Mediterranean Sea as well as the back of his hand.

Captains found he was good at making maps, and paid him to draw them, and when he was on shore he spent all his time studying charts and plans, and soon became so expert that he could support himself by preparing new charts. Yet, in spite of all his study, he found that the maps covered only a small part of the sea, and gave him no knowledge of the waters to the west. There he now began to believe the long-looked-for sea passage to the East Indies must lie.

Christopher grew to manhood, and then a chance shipwreck threw him in Lisbon, the capital of Portugal. The Portuguese were the great sailors of the age, and the young man met many famous captains who were planning trips to the western coast of Africa and about the Cape of Good Hope.

Some of the captains took an interest in the sailor who made such splendid maps and was so eager to go on dangerous exploring trips, and they brought him to the notice of the King of Portugal. One of them, Toscanelli, wrote of the young Christopher's "great and noble desire to pass to where the spices grow," and listened with interest to his plans to reach those rich spice lands by sailing west.

The ideas of Columbus seemed too visionary to most princes, and it was years before he was able to persuade the Spanish sovereigns, Ferdinand and Isabella, to grant him three small ships and enough men to start upon his voyage. But on August 3, 1492, he finally set sail from Palos, in Spain.

All the world knows the history of that great voyage, of the tremendous difficulties that beset Columbus, how his men grew fearful and would have turned back, how he had to change the ship's reckoning as he had seen his cousin change the compass, how he had sometimes to plead with his men and sometimes to threaten them.

In time he found boughs with fresh leaves and berries floating on the sea, and caught the odor of spices from the west. Then he knew he was nearing that magic land of riches sailors dreamt of, and thought he had found the shortest passage to the East Indies and Cathay. That would have been a wonderful discovery, but the one he was actually making was infinitely greater. Instead of a new sea passage he was reaching a new continent, and adding a hemisphere to the known world.

Such was the result of the dreams and ambitions of the boy born and bred in the old seaport of Genoa.

Chapter II

Michael Angelo

The Boy of the Medici Gardens: 1475-1564

The Italian city of Florence was entering on the Golden Age of its history toward the end of the fifteenth century. Lorenzo, called the Magnificent, was head of the house of Medici, and first citizen of the proud Republic. He was himself an artist, a poet, and a philosopher; he loved the beautiful things of life, and had gathered about him a little court of men of genius.

Florence at that time was also a great business city, and among the prominent merchant families was that of the Buonarotti. Ludovico Buonarotti had several sons, and he had named his second child Michael Angelo, and had planned that he should follow him in trade. Fortunately for the world, however, the boy had a will of his own.

Even while he was still in charge of a nurse, and was just beginning to learn to use his hands, he would draw simple pictures and paint them whenever he had the chance. His father had little use for a painter, and sent the boy to the grammar school of Francesco d'Urbino, in Florence, thinking to make a scholar of him. There were, however, many studios in the neighborhood of the school, and many artists at work in them, and the boy would neglect his studies to haunt the places where he might see how grown men drew and painted.

Watching the artists, young Michael Angelo soon formed a lasting friendship with a boy of great talent a few years older than himself, by name Francesco Granacci. This boy was a pupil of Domenico Ghirlandajo, a very great painter. The more Michael Angelo saw Granacci and his work in the studio the more he longed for a chance to study painting. He could think of nothing else; he begged his father and uncles to let him be an artist instead of a merchant or a scholar. But the father and uncles, coming from a long line of successful merchants, treated the boy's requests with scorn.

Michael Angelo was determined to be an artist, however, and finally, though with the greatest reluctance, his father signed a contract with Ghirlandajo by which the boy was to study drawing and painting in his studio and do whatever other work the master might desire. The master was to pay the boy six gold florins for the first year's work, eight for the second, and ten for the third.

The young Buonarotti found plenty of work to be done in his master's studio. Besides the regular day's work he was constantly painting sketches of his own, and trying his hand at a dozen different things. His eye and hand were most surprisingly true. Time and again the master or some of the older students, coming across the boy at work, would be held spellbound by his skill.

One day when the men had left work the boy drew a picture of the scaffolding on which they had been standing and sketched in portraits of the men so perfectly that when his master found the drawing he cried to a friend in amazement, "The boy understands this better than I do myself!"

There was little in the world about him that this boy failed to see. He soon painted his first real picture, choosing a subject that was popular in those days, the temptation of St. Antony. All kinds of queer animals figured in the picture, and that he might get the colors of their shining backs and scales just right he spent days in the market eagerly studying the fish there for sale. Again the master was amazed at his pupil's work, and now for the first time began to feel a certain envy of him.

This feeling rapidly increased. The scholars were often given some of Ghirlandajo's own studies to copy, and one day Michael Angelo brought the artist one of the studies which he had himself corrected by adding a few thick lines. Beyond all doubt the picture was improved. It was hard, however, for the master to be corrected by his own apprentice, and soon after that the boy's stay in the studio came to an end. Fortunately his friend Granacci had already interested the great patron, Lorenzo de' Medici, in the young Buonarotti and he was now invited to join the band of youths of talent who made the Medici's palace their home.

In Lorenzo's palace young Michael Angelo was very happy. He was fond of the Medici's sons, boys nearly his own age; like almost all the rest of Florence he worshiped the citizen-prince whose one desire seemed to be that Florence should be beautiful; and he was happiest of all in the chance to study his own beloved art.

In May of each year Lorenzo gave a pageant, and the spring in which Michael Angelo came to the palace Lorenzo placed the carnival in charge of the boy's friend, Francesco Granacci. Day by day the boys planned for the great procession. At noon they were free from their teachers, and then they would scatter to the gardens.

One such May noon, when the sun was hot, a group of them ran out from the palace, and threw themselves on the grass in the shade of a row of poplars. They were all absorbed in the one subject; their tongues could scarcely keep pace with their nimble fancies.

"What shalt thou go as, Paolo?" said one. "I heard Messer Lorenzo say that thou shouldst be something marvelously fine; but what can be so fine as Romulus in a Roman triumph?"

"I am to be the thrice-gifted Apollo, dressed as your Athenians saw him, with harp and bow, and the crown of laurel on my head. That will be a sight for thee, Ludovico mio, and for the pretty eyes of thy Bianca also." Paolo laughed as one who well knew the value of his yellow locks and blue eyes in a land of brown and black. "What art thou to be in Messer Lorenzo's coming pageant, Michael?"

The young Michael, a slim, black-haired youth, was lying on his back, his head resting in his hands, his eyes watching the circling flight of some pigeons.

"I?" he said dreamily. "Oh, I have given little thought to that, I shall be whatever Francesco wishes; he knows what is needed better than any one else."

As he spoke a tall youth came into the garden and sat down in the middle of the group. He had curious, smiling eyes, and hands that were fine and pointed like a woman's. He answered all questions easily, telling each what part he was to play in the triumphal procession of Paulus Æmilius that was to dazzle the good people of Florence on the morrow. He had become chief favorite in the little court of young people that the Medici loved to have about him, and his remarkable talent for detail had made him the leader in all entertainments.

The boy Michael listened for a time to the flowing words of young Granacci, then rose and wandered to where some stone-masons had lately been at work. He stopped in front of a block of marble that was gradually taking the form of the mask of a faun.

Near the block stood an antique mask, a garden ornament, and this the boy studied for a few moments before he picked up one of the mason's deserted tools and began to cut the stone himself.

The gay chatter under the poplars went on, but the boy with the chisel, lost in thought, his heavy brows bent into a bow, chipped and cut, forgetful of everything else. A half hour passed, and a long shadow fell across the marble. Michael looked up to see his patron, Lorenzo, standing beside him. The boy glanced from the fine, keen face of the Medici to the marble mask of the old faun in front of him.

"Well, sirrah," said Lorenzo, half seriously, half in jest, "what wilt thou be up to next?"

"Jacopó, one of the builders, gave me a stone," answered the boy, "and told me I might do what I would with it. Yonder is my copy, the old figure there."

"But," said Lorenzo, critically, "your faun is old, and yet you have given him all his teeth; you should have known in a face as aged as that some of the teeth are wanting."

"True," said the young sculptor, and taking his chisel, with a few strokes he made such a gap in the mouth as no master could have improved.

The Medici watched, and when the change was made, broke into laughter. "Right, boy!" he cried. "'Tis perfect; Praxiteles himself could not have bettered that!" Then, with a quizzical smile, he looked the youth over. "I knew thou wert a painter; and now a sculptor; what will thy clever hand be doing next?"

"Bearing arms in your worship's cause, an' the saints be good!" exclaimed the boy, his deep eyes, full of admiration, on his patron's face.

"Ah," said Lorenzo, "so? Well, perhaps the day will come. Florence is like a rose-bed, but I cannot cure the city as I would of thorns." He fell into thought, then roused again. "But thou, young Michael Angelo, dost know what a time I had to make thy father let thee be a painter, and now thou addest to thy sins and cuttest in marble. Where will be the end of thy infamy?"

The boy caught the gleam in his friend's eyes, and his serious face broke into smiles.

"In Rome, Signor Lorenzo, in the Holy Father's house. There I shall go some day."

"And why to Rome?"

"Every one goes to Rome; thy marvelous pageants are Roman; art lives there."

"Yes," mused Lorenzo, "Rome on its hills is still the Eternal City. And yet in those far days to come I doubt if thou wilt be as happy as in Lorenzo's gardens. How sayest thou, boy?"

"I know not," was the answer. "Only I know that I shall go."

The laughter of the other boys came to their ears, and Lorenzo turned. "Thy faun is done; to-morrow will I speak with Poliziano of our new sculptor. What is Granacci saying over there? Come with me and listen." So, the prince's arm resting affectionately on the boy's shoulder, they crossed the garden to the noisy group.

Life was gay then in Florence. Lorenzo de' Medici was ruling the turbulent city by keeping it occupied with merrymaking, by beautifying its squares with priceless treasures, by helping its poor but ambitious children to win their heart's desires, by mingling with the citizens at all times, and writing them ballads to sing, and giving them masques to act. His house was open to the great men of Italy; on his entertainments he lavished his wealth, set no bounds to the means he gave Granacci and the others to make the pageants gorgeous, and superintended everything with his own wonderfully keen eye for beauty.

The triumphal procession of Paulus Æmilius on the morrow after the little scene in the gardens was an all-day revel. The good folk of Florence left their shops and homes and lined the streets, and for hours floats drawn by prancing horses and picturing great scenes in Roman history passed before the delighted people's eyes. Among the warriors, the heroes, the nymphs and fauns, they recognized their neighbors' children or their own sons and daughters; they were all parcel of it; it was their own triumph as well as Rome's. Girls sang and danced and smiled, boys posed and cheered and played heroic parts, the whole youth of the city spent the day in fairy-land.

Chief among the boys was the little group of artists who were studying in Lorenzo's mansion, and chief among these Granacci, who was Master of the Revels, Paolo Tornabuoni, who made a wonderful Apollo, seated on a golden globe playing upon a lyre, and the dark-browed Michael Angelo, clad in a tunic, one of the noble youth of early Rome. His father, Ludovico Buonarotti, and his mother, Francesca, were in the crowd that watched him pass.

"Yonder he goes," cried the proud mother; "dost see thy son, Ludovico?" But her husband scowled; he had little use for a son of his who had rather be painter than merchant.

A year of happiness passed for the boys in the Medici gardens, and then the skies of Florence darkened. A monk from San Marco named Savonarola raised his voice to shame the gay people of their extravagance, and his bitter tongue sought out Lorenzo the Magnificent as chief offender. The boy Michael Angelo went to hear Savonarola preach, and came away heavy of mind and heart. He heard the beautiful things of the world assailed as sinful, and his beloved master called a servant of the Evil One. A winter of reproach came upon the city, and when it ended, and Lent was over, darkness fell, for Lorenzo lay dead at his summer home of Careggi, in 1492—the year when Columbus discovered America.

For a long time Michael Angelo, stunned by his patron's loss, could do no work, and when at last he found the heart to take up his brush and palette it was no longer in the great house of the Medici, but in a little room he had arranged for himself as a studio under his father's roof.

He was not long left to work there in peace; the three sons of Lorenzo, boys of nearly his own age, who had been playmates with him in the gardens, and had studied with him under the same masters, needed his help. The great Medici had said, long before, that of his three sons one was good, one clever, and the third a fool. Giulio, now thirteen years old, was the good one; Giovanni, seventeen years old, already a Prince Cardinal of the Church, was the clever one, and Piero, the oldest, now head of the family in Florence, was the fool.

The storm raised by Savonarola was ready to break about Piero de' Medici's head, and such friends as were still faithful to him he gathered about him at his house. Michael Angelo, his old playmate, was among the number, and so he again moved to the palace. For a brief time they sought to win back the favor of the people by a return to the old-time magnificence.

With no wise head to guide, the youths were soon in sore straits. Their love of art, their study of the poets, their attempt to revive the history of Greece and Rome were all scorned and mocked at as so much wanton dissipation. The boys drew closer together; the fate of their house hung trembling in the balance.

Then one morning a young lute-player named Cardiere came to Michael Angelo and, drawing him aside from the others, told him that in a dream the night before, Lorenzo had appeared to him, robed in torn black garments, and in deep, melancholy tones had ordered him to tell Piero, his son, that he would soon be driven out from Florence, never to return. Michael Angelo told the musician to tell Piero, but the latter was too frightened to obey.

A few days later he came again to Michael Angelo, this time pale and shaking with fear, and said that Lorenzo had appeared to him a second time, had repeated what he had said to him before, and had threatened him with dire punishment if he dared again to disobey his strict command.

Alarmed at the news Michael Angelo spoke his mind to Cardiere and bade him set off at once to see Piero, who was at Careggi, and give him his father's warning. Cardiere, half-way to Careggi, met Piero and some friends riding in toward Florence. The minstrel stopped their way and besought Piero to hear his story. The young Medici bade him speak, but when he had heard the warning he laughed, and his friends laughed with him.

Bibbiena, one of Piero's closest friends, and later to be the subject of one of Raphael's masterpieces, cried aloud in scorn to Cardiere: "Fool! Dost think that Lorenzo gives thee such honor before his own son that he would thus appear to thee rather than to Piero?" With laughter at Cardiere's crestfallen face the gay troop rode on, and the poor messenger of evil tidings returned slowly with his news to Michael Angelo.

By now the boy sculptor was thoroughly alarmed. Like almost every one else of that age he believed in portents and visions; he therefore took Cardiere's story to heart, and in addition he could see for himself that the foolish, headstrong Piero was taking no steps to turn the growing discontent. He hated to leave his friends, but knew that they would pay no heed to his warnings. So, after much hesitation, he decided, with two comrades of about his own age, to go to Venice and seek work in that quieter city.

Ordinarily it would have taken the three boys about a week to ride from Florence to Venice, but at that time French troops were scattered through the country, and they had to follow a roundabout course to reach the city by the sea. They had very little money, and had gone only a short distance when this small amount was exhausted. By that time they had reached the city of Bologna, and there they turned aside.

Like most of the Italian cities Bologna tried to keep itself independent, and to this end the ruling family had made a strange law with regard to foreigners. Every stranger entering the city gates had to present himself before the governor and receive from him a seal of red wax on the thumb. If a stranger neglected to do this, he was liable to be thrown into prison and fined.

The boy Michael Angelo and his two friends knew nothing of this odd law, and entered the city gaily, without having the necessary wax on their thumbs. As soon as this was noticed they were seized, taken before a judge, and sentenced to pay six hundred and fifty lire. They had not that much money between them, and so for a short time were placed under lock and key.

Fortunately news of the boys' arrest came to a nobleman of the city who was much interested in art and who had already heard of Michael Angelo's ability. He at once had the boys set free, and invited Michael Angelo to visit him at his home. But Michael did not wish to leave his friends, and felt that it would be an imposition for the three of them to accept the invitation.

When he spoke in this fashion to the nobleman the latter was very much amused. "Ah, well," said he, "if things stand so I must beg of you to take me also with your two friends to roam about the world at your expense." The joke showed the boy the absurd side of the matter. He gave his friends the little money he had left, said good-bye to them, and accepted the invitation to stay in Bologna.

A very short time after, Piero de' Medici, driven from Florence by an angry people, came to Bologna and met his old friend of Lorenzo's gardens. For a short time the boys were together, then the young Medici set out to seek aid from other cities, in an attempt to rebuild his family fortunes.