10,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Elliott & Thompson

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

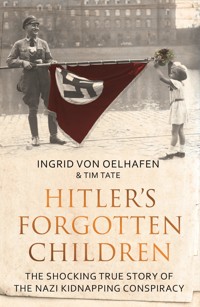

'More than 70 years ago I was a "gift" for Adolf Hitler. I was stolen as a baby to be part of one of the most terrible of all Nazi experiments: Lebensborn.' The Lebensborn programme was the brainchild of Himmler: an extraordinary plan to create an Aryan master race, leaving behind thousands of displaced victims in the wake of the Nazi regime. In Hitler's Forgotten Children Ingrid von Oelhafen shares her incredible story as a child of the Lebensborn: a lonely childhood with a distant foster family; her painstaking and difficult search for answers in post-war Germany; and finally being reunited with her biological family – with one last shocking truth to be discovered.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 323

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

This book is dedicated to all the victims of Nazi Germany –men, women and, above all, children – and to those throughoutthe world today who suffer from the persisting evil whichteaches that one race, creed or colour is superior to another.

CONTENTS

Preface

ONE

August 1942

TWO

Year Zero

THREE

Escape

FOUR

Home

FIVE

Identity

SIX

Walls

SEVEN

Source of Life

EIGHT

Bad Arolsen

NINE

The Order

TEN

Hope

ELEVEN

Traces

TWELVE

Nuremberg

THIRTEEN

Rogaška Slatina

FOURTEEN

Blood

FIFTEEN

Pure

SIXTEEN

Taken

SEVENTEEN

Searching

EIGHTEEN

Peace

Afterword

Acknowledgements

Index

PREFACE

Blood runs through this story. The blood of young men spilled on the battlefields of war; the blood of civilians that ran through the gutters of cities, towns and villages across Europe; the blood of millions destroyed in the pogroms and death camps of the Holocaust.

But blood, too, as an idea: the Nazi belief – absurd as this seems today – in ‘good blood’, precious Ichor to be sought out, preserved and expanded. And with it, the inevitable counterpart: ‘bad blood’, to be ruthlessly eradicated.

I was born in 1941 in the depths of the Second World War. I grew up in its wake, and under the shadow of its brutal progeny, the Cold War.

My history is the history of millions of ordinary German men and women like me. We are the victims of Hitler’s obsession with blood, as well as the beneficiaries of the post-war economic miracle that transformed our devastated and pariah nation into the powerhouse of modern Europe. Our story is that of a generation raised in the shadow of infamy, but which found a way to struggle towards honesty and decency.

But my own story is also that of a much more secret past, still cloaked in silence and shrouded in shame.

I am a child of Lebensborn.

Lebensborn is an ancient German word meaning ‘fountain of life’, twisted and distorted by the word-smelters of National Socialism. What did it mean in the madness of Nazism? What does it mean today? My search for the answers – to uncover my own story – has taken me on a long and painful road: a physical journey that has led me across the map of modern Europe. It has been an historical expedition, too: an often uncomfortable return to the Germany of more than seventy years ago, and into the troubled stories of those countries overrun by Hitler’s armies.

The journey has also forced me to make a psychological voyage into everything I have known and grown up with: a fundamental questioning of who I am, and what it means to be German. I will not pretend that this is a simple story: it will not always be easy to read. But neither has it been easy to live.

I am not, by nature, overtly emotional. The expression of emotion, such a commonplace thing in twenty-first-century society, does not come easily to me. I have spent my life attempting to suppress my inner self, to subordinate my feelings to the circumstances in which I have grown up, as well as to the needs of others.

But this is a story which, I believe, needs to be heard. More, much more, it needs to be understood. It is not unique, in that there are others who have endured much of what has shaped my life. But while I share a common thread with thousands of others who passed through the vile experiment of Lebensborn, to the best of my knowledge no one else shares the particular twists of fate, history and geography that have defined my seventy-four years on earth.

Lebensborn. The word runs through my life like the blood coursing through my body. To see it, to understand it, demands much more than a superficial examination. The search for the roots of this story requires a deep and intrusive investigation of the most hidden places.

We must start in a town and a country that no longer exist.

ONE | AUGUST 1942

‘Men … must be shot, the women locked up and transported to concentration camps, and the children must be torn from their motherland and instead accommodated in the territories of the old Reich.’REICHSFÜHRER-SS HEINRICH HIMMLER, 25 JUNE 1942

Cilli, German-occupied Yugoslavia, 3–7 August 1942

The schoolyard was crowded. Hundreds of women – young and old – clutched the hands of their children and found what space they could in the packed courtyard. Nearby, Wehrmacht soldiers, rifles slung over their shoulders, looked on as the families slowly drifted in from towns and villages across the area.

These women had been summoned by their new German masters, ordered to bring their children to the school for ‘medical tests’. Upon arrival they were arrested and told to wait. Otto Lurker, commander of the police and security services for the region, watched relaxed and impassive – his hands resting comfortably in his pockets – as the yard filled with families. Once, Lurker had been Hitler’s gaoler: now he was the Führer’s leading henchman in Lower Styria. He held the rank of SS-Standartenführer – the paramilitary equivalent of a full colonel in the army – but that summer’s morning he was casually dressed in a two-piece civilian suit.

Yugoslavia had been under Nazi rule for sixteen months. In March 1941, with the surrounding countries of Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria having recently joined the Reich’s alliance of Balkan nations, Hitler put pressure on the kingdom’s ruler, the Regent Prince Paul, to fall into line. He and his cabinet bowed to the inevitable, formally tying Yugoslavia to the axis powers, but the Serb-dominated army launched a coup d’état, replacing Paul with his seventeen-year-old second cousin, Prince Peter.

News of the revolt reached Berlin on 27 March. Hitler took the coup as a personal insult and issued Directive 25, formally designating the country an enemy of the Reich. The Führer ordered his armies ‘to destroy Yugoslavia militarily and as a state’. A week later, the Luftwaffe began a devastating bombing campaign while divisions of Wehrmacht infantry and tanks of the Panzer Corps swept through towns and villages. The Royal Yugoslavian Army was no match for Germany’s Blitzkrieg troops: on 17 April the country surrendered.

The occupying troops immediately set about fulfilling Hitler’s instruction to dismantle all vestiges of the state. Some 65,000 people – primarily intellectuals and nationalists – were exiled, imprisoned or murdered, their homes and property handed over to their new German masters. The Slovene language was prohibited.

But for the rest of 1941 and throughout the first half of 1942, partisan groups, led by the communist Josip Broz Tito, fought a determined campaign of resistance. Germany retaliated with a brutal crackdown: the Gestapo swooped on fighters and civilians alike, deporting thousands to concentration camps across the Reich. Others were executed as a warning against resistance. In the nine months following September 1941, 374 men and women were lined up against the walls of the prison yard at Cilli and summarily shot. Photographers recorded the murders for the purposes of both posterity and propaganda.

On 25 June 1942, Heinrich Himmler – the second most powerful and feared man in Nazi Germany – issued orders to his secret police and SS officers for the elimination of partisan resistance.

This campaign possesses every required element to make harmless the population which has supported the bandits and provided them with human resources, weapons and shelter. Men from such families, and often even their relatives, must be shot, the women locked up and transported to concentration camps, and the children must be torn from their motherland and instead accommodated in the territories of the old Reich. I expect to be provided with a special report on the number of children and their racial values.

Against this bloody backdrop, 1,262 people – many the surviving relatives of those executed as an example to the rest of the population – assembled in the schoolyard that August morning to await their fate.

Among them was a family from the nearby village of Sauerbrunn. Johann Matko came from a family of known partisans: his brother, Ignaz, had been one of those lined up and shot against the wall of Cilli prison in July. Johann had been dragged off to Mauthausen concentration camp. After seven months in the camp he was allowed to return home to his wife, Helena, and their three children: eight-year-old Tanja, her brother Ludvig – then six – and nine-month-old baby Erika.

When all the families were accounted for, an order was given to separate them into three groups – one each for the children, the women, and the men. Under Lurker’s direction the soldiers moved in and pulled children from the grasp of their mothers; a local photographer, Josip Pelikan, recorded the harrowing scene for the Reich’s obsessive archivists. His rolls of film captured the fear and alarm of women and children alike: his shots included scores of toddlers held in low pens of straw inside the school buildings.

As the mothers waited outside, Nazi officials began a cursory examination of the children. Working with charts and clipboards, they painstakingly noted each child’s facial and physical characteristics.

These, though, were not ‘medical tests’ as any doctor would know them: instead they were crude assessments of ‘racial value’ which assigned each youngster to one of four categories. Those who met Himmler’s strict criteria for what a child of true German blood should look like were placed in Category 1 or 2: this formally registered them as potentially useful additions to the Reich population. By contrast, any hint or trace of Slavic features – and certainly any sign of ‘Jewish heritage’– consigned a child to the lowest racial status of Categories 3 and 4. Thus branded as Untermensch, their value was no more than future slave labour for the Nazi state.

By the following day this rudimentary sifting had finished. Those children deemed racially worthless were handed back to their families. But 430 other youngsters, from young babies to twelve-year-old boys and girls, were taken away by their captors. Marshalled by nurses from the German Red Cross, they were packed into trains and transported across the Yugoslavian border to an Umsiedlungslager – or transit camp – at Frohnleiten, near the Austrian town of Graz.

They did not stay long in this holding centre. By September 1942, a further selection had been made – this time by trained ‘race assessors’ from one of the myriad organisations established by Himmler to preserve and strengthen the pool of ‘good blood’.

Noses were measured and compared to the official ideal length and shape; lips, teeth, hips and genitals were likewise prodded, poked and photographed to sort the genetically precious human wheat from the less-valuable chaff. This finer, more rigorous sieving re-assigned the captives within the four racial categories.

Older children newly listed in Categories 3 or 4 were shipped off to re-education camps across Bavaria in the heartland of Nazi Germany. The best of the younger ones in the top two categories would – in time – be handed over to a secretive project run by the Reichsführer himself. Its name was Lebensborn and among the infants assigned to its care was nine-month-old Erika Matko.

TWO | YEAR ZERO

‘It is our will that this state shall endure for a thousand years. We are happy to know that the future is ours entirely!’’ADOLF HITLER:TRIUMPH OF THE WILL, 1935

At 2.40 a.m. on Monday, 7 May 1945, in a small red-brick schoolhouse in the French city of Reims, Generaloberst Alfred Jodl, Chief of the German Armed Forces High Command, signed the unconditional surrender of the Thousand Year Reich. The five terse paragraphs of this act of capitulation handed over Germany and all its inhabitants to the mercy of the four victorious Allied powers – Britain, America, France and Russia – from 11.01 p.m. the following night.

A week earlier, Hitler and most of his inner circle had committed suicide in the bowels of the Berlin Führerbunker. Heinrich Himmler – Hitler’s chief henchman and the man in charge of the entire Nazi apparatus of terror – was on the run, disguised in the coarse grey serge of an enlisted soldier and equipped with forged papers proclaiming him to be a humble sergeant.

It was over: six years of ‘total war’ in which my country had murdered and plundered its way across Europe. Now we had to live with the peace.

Who were we then, on that May morning? What was Germany – once the begetter of Bach and Beethoven, Goethe and Schiller – in the aftermath of the brutality of the Blitzkrieg, let alone the Final Solution? What would peace look like to the victors and to the vanquished?

A new term was coined to describe our situation in 1945: Die Stunde Null. Literally translated, this means ‘zero hour’ but for the smouldering remains of Germany – a country of ruins, shame and starvation – it was more accurately ‘Year Zero’: both an end and a beginning.

What did it mean to be a German from 11.01 p.m. on Tuesday, 8 May 1945? To the Allies – the new owners of every metre of turf and of every individual life from the Maas in the west to the Memel in the east – it meant subjugation, suspicion and suppression. Never again, said the four occupying powers, would the poisonous twin rivers of German nationalism and militarism be allowed to rise up and flood the continent. Within hours there would be mechanisms and procedures in place to enforce this ideal – systems that, though I was too young to know then, would direct the course of my life.

To Germans, this question of identity meant something different. Something much less philosophical, something that could perhaps be categorised as the three Ps: physical, political and psychological. Of these, the greatest – the most pressing – was undoubtedly the physical.

Germany in May 1945 was a wasteland of blown-up bridges, damaged roads, burned-out tanks. In the dying weeks and months of his Reich, consumed by madness and impotent rage, Hitler had issued orders to create ‘fortress cities’. The Fatherland was to be defended to the last drop of pure German blood and the last brick of German building. There was to be no surrender but, instead, a Götterdämmerung of flame and sacrifice to mark the final days of his self-proclaimed Master Race.

The result was less a noble funeral pyre than a thousand-mile-wide bonfire of his vanity. Forced to fight for every inch of territory – and bludgeoned by Allied carpet-bombing – Germany was reduced to a post-apocalyptic desert. Piles of rubble lay where buildings had once stood: in Berlin alone there were seventy-five million tons of it piled up along and across almost every street. Other German cities suffered equally, obliterated by bombing and house-to-house fighting that damaged or left derelict seventy per cent of their buildings. And everywhere, now hollow and haggard, a once-proud people who had subjugated those they believed to be inferior.

Newsreels and photos (Allied ones, since the German press had been shut down from the moment of surrender) captured previously unimaginable scenes. Clustered around half-destroyed buildings, blown apart so that the remnants of a once normal life were exposed for all to see – a fireplace, shreds of wallpaper, the remains of a toilet – were the living ghosts of women and children. Orphans, refugees, the aged and the wounded: everywhere a dystopian tableau of anonymous bodies lying dead in the street, watched – or more often avoided – by skeletal figures who might well soon join them.

All of Germany, at least in the cities, was picking through debris, creating makeshift shelters, scrounging for food and either hiding from or fearfully fraternising with the victorious occupying armies. Not from choice, but from necessity.

In the last weeks of the war, the country’s economy – so long directed by and for the benefit of the Nazi Party – had collapsed as badly as its buildings. Ironically, there was plenty of money, but coins and paper bills were useless: as every available resource was diverted away from the people to the needs of the army, and as explosions ripped up the railway network, preventing what food was harvested from being distributed, there was little or nothing to buy with the now-useless marks.

Nor did Germany’s new masters appear to have a coherent idea of what to do with it. Between July and August 1945, the Allied leaders – Churchill (and, later, Attlee), Truman and Stalin – met at Potsdam to plan the future. Unlike the end of the First World War, when Germany was defeated and subjected to severe punishment and reparations but not wiped from the geographical and political map, the decision was taken that the country would cease to exist once the war ended. In its place would be four separate ‘Occupation Zones’, each owned and ruled by one of the war’s victors, according to its own principles and plans.

Yet beyond that there had been little concerted thinking about what, practically, would be done with the former German state once Hitler had been defeated. France had favoured breaking the Reich into a series of small independent states while America had considered returning Germany to a pre-industrialised nation focused and dependent on farming. Washington would come to relent, to accept that requiring tens of millions of Germans to live as medieval peasants was unworkable as well as undesirable. But the Allies failed to contemplate how their separate occupations would function, or to address the monumental problem of feeding both a conquered people – a population swelled by more than ten million refugees from the east – and the massive armies imposing the peace.

There was simply not enough food – and without a functioning transport system, what little there was couldn’t be moved to the places where it was most needed. Worse, there was a widespread feeling among the occupying armies that the Germans were long overdue a taste of their own medicine: had the Nazi rampage across Europe not deliberately starved villages, cities, entire nations to the point of death?

This, then, was Hitler’s true legacy: a nation starving to death; a population reduced to a desperate struggle for survival, subsisting at best on half the calories needed to sustain life. A country not simply beaten and half-destroyed but wiped completely out of existence.

I was three and a half when peace came. A small, quiet and archetypally blonde German child, I lived in Bandekow, a tiny hamlet in the rural heart of the Mecklenburg region, with my mother, grandmother and slightly younger brother Dietmar. Our home was a big farmhouse, half-timbered and characteristic of the region, set in acres of forest. We were, I think, typical both of a particular class of pre-war Germans and, by contrast, of the post-war country at large. On both sides our family was old, well established and, notwithstanding the wrecked economy, well off.

My mother, Gisela, was the daughter of a shipping line magnate from Hamburg. The Andersens belonged to the old Hanseatic class – the patrician and prestigious ruling elite which had made its money and its name from trade since Hamburg was declared a free city by the 1815 Congress of Vienna.

Our house in Bandekow had been in my mother’s family for generations: it belonged to my great uncle, but had almost certainly been used as a country retreat in the years before 1945. Certainly, the Andersens kept their main residence in Hamburg itself and my grandfather remained there, with my grandmother dividing her time between the two homes.

Gisela was one of four Andersen children. Her brother had been killed, serving in the Wehrmacht in the last days of the war; her eldest sister was estranged – the result of some unspoken act of dishonesty that tarnished the otherwise respectable family name – but her remaining sibling, my Aunt Ingrid (known universally as Erika, or ‘Eka’), was a constant companion in my childhood. At the end of the war, Gisela was thirty-one. She was young, bright – in the brittle and privileged way of her class – and pretty. She was also married, though not, as it turned out, happily.

Hermann von Oelhafen was a career soldier. He had served with honour in the First World War: he was seriously injured in 1914, again in 1915, and, after a final wound in 1917, was awarded the Iron Cross for his pains. Like Gisela, he came from an aristocratic background: both his father and mother could boast the tell-tale ‘von’ – the mark of the upper class – in their family names.

But where Gisela was young and lively, Hermann was the complete opposite. He was thirty years older than Gisela and suffered from severe epileptic seizures. Whether these were the cause of his peevish, mean-spirited nature I do not know: what I am certain of is that their marriage – which took place in 1935, during the first confident years of Hitler’s reign – was, by 1945, effectively over. As I grew from a toddler to a young child, I rarely saw my father: we lived in the farmhouse at Bandekow, while Hermann lived 1,000 kilometres away in the Bavarian town of Ansbach.

Perhaps outwardly there was nothing very strange in a married woman living alone with her children and mother. In this our family was typical of the now-dissolved German nation in the immediate months after the war: most adult men – even the very young and the elderly – had been drafted into military service and were now either dead, missing or held in prisoner of war camps across Europe. Germany was a country – more accurately, a former country – of women and children.

But though it played its part, the war was not the prime reason for the separation of my parents. There was an unbridgeable gulf between them; an emotional fracture even less tractable or open to resolution than the divisions imposed upon their nation. I was too young to know it at the time, but it would render my childhood as bleak as the deteriorating political situation in which we found ourselves.

Politics. The second ‘P’ which defined life at the end of the war. Not politics as modern generations have come to know and disregard it; not the jockeying for position and power between rival parties in a settled democracy: politics in 1945 was truly red in tooth and claw.

The last days of the war had seen the Allied forces smashing their way through Germany from all points of the compass. American tanks and troops rolled eastward from France, Belgium and Holland; the British fought their way northwards, up through the country from Italy and Austria; and the vast armies of the Soviet Union raced westwards from what had, before the war, been Poland. For each there was an overriding imperative to conquer and control as much German territory as possible: whatever they held when the war finally ended would, under the Potsdam Agreement, become their property with little prospect of subsequent redistribution. In those last weeks of spring 1945, the borders of post-war Europe were being claimed and, at the same time, the seeds of the Cold War were being planted.

When the fighting was over, it turned out that my father’s home was in the American zone: henceforth his fate would depend on the way Washington saw its duties and rights over the territory it now owned. Bandekow, however, was in the Soviet occupation zone, and Moscow had very different ideas about how to dismantle the infrastructure of Nazi Germany – as well as what it wanted to do with its share of the former Reich.

Initially, at least, there was agreement between the Allies on the need to bring Hitler’s surviving henchmen to justice. A four-power war crimes tribunal was established to put the National Socialist machine on trial; Göring, Jodl, Hess, von Ribbentrop and twenty other leaders of the National Socialist state were locked up in cells beneath the Palace of Justice in Nuremberg to await trial for crimes of war and crimes against humanity. Other than Hitler and Goebbels, the most notable absentee from this roll call of infamy was Himmler, creator of the SS and mastermind of the Nazi’s apparatus of terror: after being captured he had committed suicide before he could be transported to Nuremberg.

The eventual trial and conviction of almost all these men was undoubtedly a triumph for justice, but it also marked the high point of cooperation between the occupying powers. After Nuremberg, America, Britain, France and the Soviet Union would each take a radically different approach to the land and populations they controlled: the individual fates of tens of millions of former Germans depended on which zone they happened to have been in when the war ended. Very soon these great political divides would change the lives of our little family for ever.

The contrast between the four occupying powers was played out first in the way they viewed Nazi Party members. Denazification was a phrase coined in Washington during the last years of war: President Franklin Roosevelt and his successor, Harry Truman, recognised that the party’s tendrils had wound themselves throughout every aspect of German life, from the political to the judicial, the public to the personal. In May 1945 there were more than eight million members of the Nazi Party – around 10 per cent of the total population. What was to be done about this entwining of the mechanics of fascism with the warp and weft of everyday life?

The search for an answer was not confined to America, of course. Each Allied power faced the problem of how to pull out the roots of National Socialism while ensuring that its own zone of occupation kept functioning. The first step was to outlaw the party. On 20 September 1945, Control Council Proclamation No. 2 announced that ‘The National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP) is completely and finally abolished and declared to be illegal’ throughout the former Reich.

But the party itself was only the most visible of a byzantine tangle of Nazi organisations. Beneath it were more than sixty other official associations, ranging from internationally notorious bodies like the SS, Gestapo and Hitler Youth to more obscure societies (even within Germany) such as the Reich Committee for the Protection of German Blood and the Deutsche Frauenschaft, the National Socialist Women’s Movement. All were duly made illegal: more importantly, previous association with any one of them would be enough to mark someone as a possible Nazi sympathiser.

Neither Hermann nor Gisela were – to the best of my knowledge – Nazi Party members. I never heard them express fascist opinions or support for Hitler. But their personal histories (my father as a career soldier, who had been a desk officer in the Wehrmacht for much of the war; my mother as a former member of Deutsche Frauenschaft) must have led to some investigation by the denazification officials of their respective Occupation Zones.

The Americans were initially fiercely committed to denazification, but quickly became the most pragmatic of the occupying armies. Washington’s military government realised that, however desirable, widespread purges of suspected Nazis would mean that the entire responsibility for organising day-to-day life fell exclusively on its shoulders – a burden that, for a war-weary nation anxious to bring its troops home, was simply too onerous.

And so while my father, like every adult living in the American zone, was required to fill out a questionnaire (termed variously a Fragebogen or a Meldebogen) in which he affirmed that he had never been a member of any Nazi organisation, there was little follow-up or detailed examination of these self-declarations. With little or no oversight, most applicants were issued with official documents pronouncing them to be ‘good Germans’, free of the stain of fascism. They quickly became known as Persilschein – pieces of paper that were able to wash the past as clean as any soap powder.

The Soviet approach was very different. Perhaps because it had suffered greater losses and devastation than any of the four Allied powers – or, more likely, because Stalin had clear plans for the future of the Soviet zone – Moscow adopted a much less relaxed approach.

The Soviet Military Administration in Germany – known by its acronym, SMAD – controlled a vast swathe of territory from the Oder river in the east to the Elbe in the west. On April 18, 1945, Lavrenti Beria, Stalin’s much-feared head of secret police, issued order Number 00315: it mandated the immediate internment of active Nazis and senior members of Party organisations. No investigations were required prior to these arrests. Ultimately, 123,000 Germans were rounded up and incarcerated in ten special camps set up across the Soviet zone.

The existence of these prisons – run by the NKVD, Stalin’s equivalent of the Gestapo, and frequently on the site of former Nazi concentration camps – was in itself a secret. No contact was allowed between prisoners and the outside world, but inevitably word did leak out: the often random nature of arrests and internment (by February 1946, genuine Nazi Party members formed less than half of the total number of prisoners), and fear of being dragged off to the network of Schweigelager (literally, ‘Silence Camps’) weighed heavily on an already fearful German population under Soviet military rule.

Almost anything – anonymous denunciation, previous membership of an obscure Nazi society or contact with anyone in the other three Occupation Zones – was enough to earn a knock on the door and transport to a Schweigelager. All too often this proved to be a one-way ticket: almost 43,000 men and women would die behind the barbed wire of these post-war concentration camps.

Did my mother worry about the risk that her involvement with Deutsche Frauenschaft posed to our household in Bandekow? I do not know: the von Oelhafens were a close-lipped family, rarely given to discussion of emotions, much less those of the past. It would be many years before I discovered the secret at the heart of my childhood, a secret that tied Gisela, Hermann and me to a sinister Nazi organisation, one which would certainly have spelled trouble for us if SMAD came to hear of it.

Was this an added worry, clouding my mother’s mind? Again, I do not know. What I do know is that as summer turned to winter, Gisela was terrified of something else: rape.

Throughout 1945, as the Soviet Army fought its way into Germany, its troops mastered one phrase above all: Komm, Frau. It was an order that brooked no disobedience and led to the same inevitable conclusion. Tens of thousands – perhaps ten times that number – of German women paid, with their bodies, the price for Hitler’s brutal treatment of Russian cities and populations. Rape was so commonplace in the Soviet sector that the question for many women, of all ages, was not whether they had been violated but how many times.

It was also quasi-officially sanctioned. Although SMAD commanders in some parts of the Occupied Zone paid lip service to stamping out the violation of German women, in reality others paid a heavy price for doing so. One young Red Army captain, Lev Kopelev, intervened to stop the gang rape of a group of girls and was sentenced for his troubles to ten years in a labour camp: a tribunal convicted him of the crime of ‘bourgeois humanism’.

It was, of course, true that neither the internment camps nor rape were confined to the Soviet sector. The Americans imprisoned thousands of suspected Nazis, often in appalling conditions for years, and French troops frequently ravaged German women in cities under their control. But in the final months of the war, Hitler and Goebbels had fanned the flames of national fear by issuing a constant stream of propaganda about the brutality of the Red Army – and from the moment they fought their way onto German soil, the Soviet occupiers fulfilled the worst of these predictions.

Our family was as vulnerable as any, if not more so. My mother and my Aunt Eka were young and pretty and we came from the hated bourgeoisie: our home was large, comfortable and well-stocked with food from the farm, but it was also isolated, and my brother was the only man in the household. The fear of rape hung over us as the winter wore on. My mother would later remember – one of only a sparse handful of personal feelings she ever shared with me – hiding under the bed whenever she heard rumours that Red Army soldiers were in the area.

But however debilitating the fear, in truth we were better off than most of the population in the Soviet Zone. We had a roof over our heads, unlike the vast majority of people in the bombed-out cities. The winter of 1946–7 was one of the harshest in living memory: temperatures plummeted to -30° and for the millions struggling to exist in the bombed-out basements of their former homes there was no protection from the biting cold. And since what remained of the rail network after the final, disastrous months of fighting was rapidly dismantled by the Soviet Army and taken back east as war reparation, there was little coal to be had: thousands of people simply froze to death.

But it was food – or rather, the lack of it – that soon became the overriding preoccupation. German ration cards were no longer valid: whatever limited provisions had previously been available were now being claimed by SMAD to feed the Red Army. In cities across the country, hunger joined fear as the measure of existence.

In the areas under Moscow’s control, new rationing measures were introduced. The Russians created a new five-tier system: the highest level was reserved, bizarrely, for intellectuals and artists; the next level down was assigned to the women – Trümmerfrauen, as they were called – who worked in chain gangs, tearing down and clearing semi-derelict buildings, often with nothing more than their bare hands. This was much more valuable than the official wages of 12 Reichsmarks they received for cleaning up every thousand bricks. Hard physical labour was the only way to survive and, in the ruins of the nation, Germany’s women dug for the salvation of their families.

The levels of rationing below this fell incrementally and dramatically. The lowest card, nicknamed the Friedhofskarte (literally meaning ‘cemetery ticket’), was issued to those who performed no useful function in the eyes of our Soviet masters: housewives who did no work and the elderly.

Two new words joined the lexicon of post-war lives that winter. The first was Fringsen: it emerged after the Catholic cardinal of Cologne, Josef Frings, gave formal blessing to what many of his flock were already doing – stealing in order to survive. Crime rose dramatically: in addition to the uncountable tally of thefts and rapes by Red Army soldiers, Germans under Soviet occupation began preying on each other. Berlin alone averaged 240 robberies and five murders every day. Urban crime may not have been a pressing concern for the von Oelhafens, living in the relative security of rural Mecklenburg, but the second new word had a very real meaning. Hamstern meant, quite literally, ‘to hamster’: in practice, it was a constant procession of city dwellers to and from the countryside, desperate to trade their few remaining possessions for the food we had in relative abundance.

This was the reality of Stunde Null: an existence defined by three constant companions: fear – especially of the Red Army and of its determination to exact revenge on German civilians for Hitler’s war – hunger and cold. This was Germany, my country and my life on my fourth birthday. This was the legacy of the glorious Reich. And there was worse in store. Throughout 1946, as relations between the occupying powers worsened, Moscow’s intentions towards those under its rule in SMAD grew starker. As well as stripping the zone of wealth and food, it began the process of removing the one, flickering hope we had enjoyed when the war ended: freedom.

The boundaries between the four zones were becoming ever less passable. An ‘Inner German Border’, as SMAD termed it, had been established around the Soviet-held territory in July 1945, but since then it had been only sporadically policed. Although anyone wanting to move between the Soviet sector and the other Allied Occupation Zones officially needed an Interzonenpass, at least one and a half million Germans had managed to flee into the American or British zones. Now that began to change.

In the summer of 1947, preparations were underway for the eventual transformation of SMAD into the new communist-ruled German Democratic Republic. New contingents of Soviet soldiers were assigned to the official border checkpoints. Unofficial crossing places would soon be blocked by newly dug ditches and barbed wire barricades. The Cold War was beginning and we were living on the wrong side of the coming Iron Curtain. In the summer of 1947 my parents – separated both physically and emotionally – made a remarkable joint decision. It was time to escape.

THREE | ESCAPE

‘Ingrid is very brave and overcomes the strenuous walk without complaining.’GISELA VON OELHAFEN’S DIARY, JUNE 1947

My mother kept a journal. Unknown to me – she never told me about it, even when I was an adult – she jotted down the barest of details of my early years across a sparse handful of pages. This slim, black leather-bound notebook contains all I know about my first eight years of life.

It begins with a small black and white photo of me, three years old, barefoot and wearing shorts, captioned: ‘Bandekow – Ingrid, Summer 1944’. Over the page is an envelope dated June 4, 1944 and containing – according to my mother’s note – a few strands of my hair. If that seems fairly conventional, the sort of journal any loving mother might keep as a record of her daughter’s childhood, the rest of the content fails to match that impression. There are very few entries – no more than four or five for each of the five years my mother wrote in it. And the nature of the inscriptions themselves are curious: they are all in the third person. Gisela refers to herself as ‘Mutti