Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

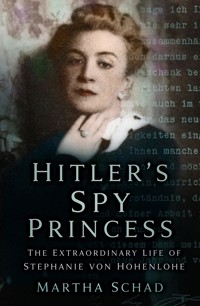

'Hold on to this letter, so that it will be evidence of how accurately I have kept you informed. I'm serious; don't throw this letter away.' Born the illegitimate daughter of Jewish parents, Princess Stephanie von Hohenlohe would rise to dizzying heights in international politics, hobnobbing with European royalty, British aristocracy – and high-ranking Nazis. She was the unofficial go-between for some of the most important people of the era, conveying secret messages and organising meetings between Adolf Hitler, Lord Rothermere, the Duke and Duchess of Windsor and more than one US president. She would even be one of only a handful of women to be awarded the Nazi Party's Gold Medal for 'outstanding service to the National Socialist movement'. But then the Second World War began, and everything changed. Hitler's Spy Princess is a tale of lovers and manipulation, cleverness and deceit in the remarkable life of the woman Hitler called his 'dear princess'.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 408

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Martha Schad was born in Munich in 1939. A freelance historian and author, she is much acclaimed in Germany and became widely known for her book Women against Hitler. She is the author of more than thirty books, which have been translated into sixteen languages and has had her writing adapted for film. She lives in Germany.

First published in 2002 by Wilhelm Heyne Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, Munich, under the title Hitlers Spionin

This English translation first published 2004

This new edition first published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Martha Schad, 2002, 2004, 2022

German edition © Wilhelm Heyne Verlag, Munich, within Verlagsgruppe Random House GmbH, 2002.

English translation © The History Press, 2004

Translation and annotation: Angus McGeoch

The right of The Author to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7524 8829 5

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

1 The Girl from Vienna

2 A Mission for Lord Rothermere

3 Hitler’s ‘Dear Princess’

4 Stephanie’s Adversary: Joachim von Ribbentrop

5 Lady Astor and the Cliveden Set

6 Stephanie, Wiedemann and the Windsors

7 Trips to the US and their Political Background

8 Rivals for Hitler’s Favour: Stephanie and Unity

9 Wiedemann’s Peace Mission

10 Mistress of Schloss Leopoldskron

11 Wiedemann’s Dismissal: Stephanie Flees Germany

12 The Lawsuit against Lord Rothermere

13 The Spy Princess as a ‘Peacemaker’ in the US

14 Stephanie’s Fight against Expulsion and Internment

15 The International Journalist

Appendices

I Stephanie Von Hohenlohe: ‘Prefatory Morning Monologue’

II Letter from Adolf Hitler to Lord Rothermere, 7 December 1933

III Letter from Crown Prince Wilhelm of Germany to Lord Rothermere, 20 June 1934

IV Letter from Adolf Hitler to Lord Rothermere, 3 May 1935

V Letter from Adolf Hitler to Lord Rothermere, 19 December 1935

VI Stephanie von Hohenlohe: Anniversary of Disaster

Notes

CHAPTER ONE

THE GIRL FROM VIENNA

‘“A woman’s will is God’s will” was a saying I often heard as a little girl in Vienna.’ It is with this sentence that Stephanie Richter, later to become Princess von Hohenlohe-Waldenburg-Schillingsfürst, begins the autobiography that she never completed. It was the motto she believed had governed her extraordinary life, a life which spanned the years from 1891 to 1972, and thus saw the decline and fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the First and Second World Wars and the postwar period in Germany and the United States.1

Stephanie Maria Veronika Juliana Richter was born in a Viennese town house, Am Kärnterring 1, directly opposite what was then the Hotel Bristol, on 16 September 1891. She was given the first of her names in honour of Crown Princess Stephanie, the consort of Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria, who had committed suicide at Mayerling in 1889.

Stephanie described her father, Dr Johann Sebastian Richter, as a successful lawyer. He had really wanted to become a priest, but then fell in love with Ludmilla Kuranda and married her. Stephanie saw her parents – neither of them Jewish, she was at pains to point out – as people who should never have married one another, yet she and her sister Milla (christened Ludmilla, and five years her senior) nonetheless had a happy childhood. And in a ‘morning monologue’, a kind of one-sided conversation with her maid Anna, Stephanie von Hohenlohe later wrote: ‘I grew up in Vienna … I loved Vienna … I was a Viennese girl. And like all the others, I sang: Wien, Wien nur Du allein …’2

Her father, as she remembered him, was incredibly kind and full of tender affection for her, but her mother was excessively anxious and seemed to nag constantly. Thus she grew up a somewhat spoiled, but also rather subdued child.

When her nursemaid pushed her through the park in her pram, the little girl with the big, radiant blue eyes was always the object of admiration. Later, when she began to walk, ‘“Steffi’s little calves” (were) famous amongst all child-lovers in Vienna’.

Her mother Ludmilla came from an old Jewish family, the Kurandas of Prague. Her father, Johann (known as Hans) Richter, was a Catholic, and a few days before their wedding Ludmilla also adopted the Catholic faith. With a good income from his law practice, Hans Richter could give his family a comfortable life. Yet he was often very generous to his clients as well and even took on cases free of charge, a fact that did not please his wife, who was something of a spendthrift. On one occasion Richter was imprisoned for embezzling funds entrusted to him on behalf of a minor. Towards the end of his life he became increasingly pious. And when his health began to deteriorate, he withdrew mentally, and in the end physically as well, from all worldly things, and joined the Order of Hospitallers. He was accepted as a lay brother, which meant that his family could visit him whenever they wanted.

From Stephanie’s half-sister, the writer Gina Kaus,3 we get a more authentic account of Stephanie’s parentage: her natural father was not Hans Richter, the Viennese lawyer born on a farm in northern Moravia, but a Jewish money-lender named Max Wiener. While Richter was serving a seven-month prison sentence for the aforementioned embezzlement, his wife had a relationship with Wiener, then a bachelor, which went beyond the mere arrangement of a loan. Not long afterwards, Wiener married another woman and had a daughter, Gina. Notwithstanding, on 16 September 1891 the Richters became the proud parents of a baby girl they christened Stephanie. When Gina Kaus was very old, she was again asked about her half-sister. ‘Princess Hohenlohe was my half-sister – though maybe she never knew it,’ Gina replied. ‘My father – a very unsophisticated man – occasionally mentioned that before he married my mother he had an affair with a Frau Richter, while her husband Hans was in prison. However, Richter acknowledged the child, who was Steffi, and perhaps a sum of money changed hands …’4

Gina Kaus followed her half-sister’s hare-brained ploys with mixed feelings. Steffi repeatedly hit the headlines in Nazi Germany, and again years later in the United States.

Stephanie had a sheltered upbringing. She was very reluctant to go to day-school and was a poor pupil there. At the end of her years at school she was sent for four months to a college in Eastbourne, on the south coast of England. This was followed by piano lessons at the Vienna Conservatoire. She remembered ruefully that her teacher rapped her knuckles with a small stick whenever she played a wrong note. Stephanie’s mother wanted her to become a pianist, but her hands were so small and narrow that she could not span an octave properly, so a professional career was out of the question.

Stephanie never read a book and took no interest in such ‘feminine’ accomplishments as sewing, embroidery and crochet. Nor could she cook; she could not even boil a saucepan of water without getting someone to light the stove for her. But she adored animals. And she enjoyed sport of every kind: she played tennis, swam, sailed, hunted, cycled and rowed. She was particularly good at skating, performing waltzes on the ice, and met all her boyfriends at the Vienna Skating Club. She did not have any special friends of her own sex. At the age of 14 she was rolling her own cigarettes in the school lavatories. With her innate intelligence, she had no great difficulty in mastering foreign languages.

During a summer holiday at the lovely lakeside resort of Gmunden, in the Salzkammergut, the 14-year-old Steffi went in for the annual beauty contest, even though, as she herself writes, she was still a rather podgy teenager. Nonetheless, she won. From then on she attracted attention; other girls began to copy the hairstyle and clothes worn by ‘Steffi from Vienna’.

One of the grandest clients of her father’s law practice was the childless Princess Franziska (Fanny) von Metternich (1837–1918). She had been born the Countess Mittrowsky von Mittrowitz and was the widow of Prince von Metternich-Winneburg und Beilstein. The Grande Dame, as Stephanie later called her, liked Dr Richter’s teenage daughter and asked him if she might take her out from time to time. Richter was happy to agree to this. In this way the young Stephanie came into contact with Vienna’s exclusive aristocratic society. She quickly learned how to behave and move in those circles, and avidly acquired the lifestyle of the beau monde. People were enchanted by her smile and her charm; and her skill as a horsewoman soon won her an admirer in the person of a Polish nobleman, Count Gisycki. The Count took her to the Schloss that he owned, near Vienna. However, she rejected his proposal of marriage, since the good-looking playboy was old enough to be her grandfather, let alone her father.

Count Joseph Gisycki was divorced from an American heiress, Eleanor Medill Patterson, who had returned to the United States with their daughter Felicia. At that time no-one could have guessed that Felicia Patterson would marry a man who was to play an important part in launching Stephanie von Hohenlohe’s postwar career as a journalist; he was the influential and highly respected American columnist, Drew Pearson.

At the age of 15, Steffi had set herself an ambitious goal in life: she would marry a prince – although he would not show up until 1914, when she was 23. She claims in her memoirs, however, that she was 17 when she got married. When she was still only 15, Steffi received her next proposal of marriage, from Count Rudolf Colloredo-Mannsfeld. But she turned the nobleman down because he was such a skinflint.

With the death of Hans Richter in 1909, Stephanie’s family fell into dire financial straits. Who would lend money now to the widow and her daughters? The answer to all their problems was provided by Ludmilla’s brother. As a young hothead, Robert Kuranda had run away from home and had never been heard of again. Yet now he was standing at the door, having returned from South Africa a rich man. Kuranda made lavish financial provision for his sister Ludmilla and his nieces. While Ludmilla was apparently incapable of handling money, Stephanie invested her share well and made an excellent return. At that time her mother had another ‘informal relationship’ with a businessman. The family now had enough money to go on summer holidays abroad, and did so very frequently.

On these trips Stephanie, Milla and their mother were accompanied by Aunt Clothilde, their mother’s sister, who had been briefly married to the Vienna correspondent of the London Times, Herbert Arthur White. Clothilde owned a handsome town house in Kensington as well as a beautiful mansion on the shore of Wannsee, a lake near Berlin. She was famous for her parties. She had style and could afford to invite the most famous ballerina of the day, Anna Pavlova. There were expeditions to the spas of Marienbad and Karlsbad, to Venice, Berlin, Paris and Biarritz, to Kiel for the regatta, to the Dalmatian coast, to Corsica and to Prague.

Stephanie tells us that, at a hunt dinner given by Princess Metternich, she was asked to play something on the piano. A young man joined her at the keyboard and that is how she first met her future husband – Prince Friedrich Franz von Hohenlohe-Waldenburg-Schillingsfürst (1879–1958). The next day, Stephanie wrote, the two met again and he offered to drive her home. It was then that he noticed that Stephanie was being chaperoned by a governess. But even this obstacle was overcome, and Stephanie managed to arrange three secret trysts with the prince. ‘And within two weeks he asked me to marry him.’

When her mother found out about these clandestine walks in the park, she was furious. And Prince Friedrich Franz found relations with his future mother-in-law difficult. Stephanie was not present at the serious discussion that took place between the prince and her mother, but in the end the prince won Ludmilla over completely. ‘My future husband had, at one time, served as military attaché in St Petersburg and had a brilliant war record … And so at seventeen I got married. Half the royal houses of Europe now called me “cousin”.’ That is how Stephanie, in her autobiographical sketches, describes her path from happy-go-lucky Viennese teenager to Princess von Hohenlohe. However, she was putting this period of her life in a thoroughly idealised light as well as being dishonest about the dates.

The memoirs written by her son tell a different story. He claims that, through her rejected suitor Count Colloredo-Mannsfeld, she got to know another member of the house of Hohenlohe, Prince Nikolaus von Hohenlohe-Waldenburg-Schillingsfürst (1877–1948). However, Stephanie found him excessively arrogant and turned him down in favour of his younger brother, Prince Friedrich Franz, whom she had met while riding to hounds. The prince was searching desperately for his pince-nez, which he had lost while jumping a fence. Steffi helped him look for the spectacles and he fell in love with her. Steffi was actually about to reject his marriage-proposal as well, but her mother took charge of the situation and threatened to put Steffi into a convent if she turned Friedrich Franz down. She accepted his suit.

The prince, whose full names were Friedrich Franz Augustin Maria, was the offspring of the marriage between Prince Chlodwig Karl Joseph von Hohenlohe-Waldenburg-Schillingsfürst (1848–1929) and Countess Franziska Esterházy von Galántha (1856–84). At the time when Friedrich Franz and Stephanie planned to marry, he was military attaché at the Austro-Hungarian embassy in St Petersburg, then the Russian capital. The ambassador now had to be informed of the betrothal, as did the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Vienna. The approval of the Emperor himself had to be obtained, as well as that of the head of the house of Hohenlohe, Prince August Karl Christian Kraft von Hohenlohe (1848–1926).

Putting up the marriage banns necessitated so many formalities that in the end the prince suggested they should marry, not in Vienna, but in London. One might think that for foreigners to get married in London would have been just as difficult. However, it seems that speed was of the essence, for ‘Steffi from Vienna’ was expecting a baby – and her bridegroom was not the father! The willingness of Prince Friedrich Franz to marry Steffi may well be explained by the fact that his bride was wealthy enough to settle his not inconsiderable gambling debts – ‘debts of honour’ as he would have called them.

The actual father of the child was another man: among the many aristocratic admirers of the middle-class Steffi Richter there had been one of particularly high rank, Franz Salvator of Austria-Tuscany (1866–1939). He was the son of Archduke Karl Salvator of Austria-Tuscany and of Maria Immaculata of the house of Bourbon-Sicily. More importantly he was a son-in-law of Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria and Empress Elisabeth (‘Sissi’).

The imperial couple had four children: the Archduchesses Sophie and Gisela, the Crown Prince Rudolf and the Archduchess Marie Valerie. Sophie died young, Gisela married Prince Leopold of Bavaria, and the Crown Prince, heir to the throne, committed suicide at Mayerling as the result of a scandalous love affair. The youngest daughter Marie Valerie, who was particularly close to her mother, married the Archduke Franz Salvator on 29 July 1890 at the church in Ischl. The marriage resulted in no fewer than ten children. The Archduchess was 42 years old when, in 1911, she gave birth to her last child, Agnes, at the imperial mansion in Ischl. The baby lived for only a few hours. Marie Valerie, a very pious woman with a tendency to melancholia, spent a great deal of time alone with her children at Schloss Wallsee. Her fun-loving husband seems to have neglected her for much of the time.

The liaison between Archduke Franz Salvator and Stephanie Richter dated from 1911. And, as already mentioned, was not without consequence. When Stephanie was expecting the Archduke’s child, Emperor Franz Joseph obligingly arranged her betrothal to the aforementioned Prince Friedrich Franz von Hohenlohe-Waldenburg-Schillingsfürst. Yet the manner in which the wedding took place does not exactly suggest a marriage of true love. It was held very quietly on 12 May 1914, in London’s Roman Catholic cathedral in Westminster. Only Stephanie’s mother was present. The witnesses were hired at short notice, and the couple did not even stay at the same hotel. Stephanie appraised her new husband coolly: ‘Not tall – and I like tall men – but certainly very well-proportioned.’

Thus Stephanie Richter returned to Vienna from London as Princess von Hohenlohe-Waldenburg-Schillingsfürst. She was a citizen of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. However, at the end of the First World War in 1918, when the empire and its dual monarchy collapsed, her husband opted to take up not Austrian, but Hungarian citizenship, to which he was entitled through his Esterházy mother. Stephanie likewise held a Hungarian passport for the rest of her life.

As no mention had been made of the wedding in any Austrian newspapers, and not even announcement cards had been sent out, the young wife’s social standing in Vienna was problematic.

Seven months after the wedding, on 5 December 1914, Stephanie gave birth in a private clinic to her (illegitimate) son, Prince Franz Joseph Rudolf Hans Weriand Max Stefan Anton von Hohenlohe-Waldenburg-Schillingsfürst, always to be known as ‘Franzi’. [Note that the Christian names include those of the Austrian emperor, Stephanie’s benefactor, as well as that of her natural father, Max, and adoptive father, Hans. Tr.] At a solemn baptism in St Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna, the duties of godfather were assumed by Stephanie’s former admirer, Count Colloredo-Mannsfeld.

Franzi later described his childhood as a happy one. He spent the greater part of his early years in the elegantly furnished apartment owned by his mother and grandmother, at Kärnterring 1. Whenever the political situation seemed to be getting particularly tense, he was sent away from the city with his nursemaid. It was then that he usually went to a house near the Danube, belonging to Count Gisycki. The little boy enjoyed that very much, as he was allowed to romp around the garden with the dogs.

He began his schooling in Vienna, then followed several years in Paris. At the age of 10 Franzi went to a private boarding-school in Switzerland, Le Rosey, near Lausanne, where wealthy parents sent their hopeful offspring to be educated. (The present Prince Rainier of Monaco was a pupil there some years later.) The young Prince Franz then went on to the Collège de Normandie, near Rouen, and finally to university at Magdalen College, Oxford.

When the First World War broke out, Stephanie’s husband had to join his regiment. Touchingly, Franzi’s natural father, Archduke Franz Salvator, took care of the boy and his mother. As Stephanie herself writes, the Archduke had secured an audience for her with the Emperor in Vienna. We may suppose that this audience took place before her marriage to Friedrich von Hohenlohe, which the Emperor had commanded. Even before her liaison with Franz Salvator, Stephanie had had a brief fling with another scion of the Habsburg dynasty: Archduke Maximilian Eugen Ludwig (1895–1952), the younger brother of Emperor Karl, who in 1916 briefly succeeded Franz Joseph to the Austro-Hungarian throne. In 1917 Maximilian married Franziska Maria Anna, Princess von Hohenlohe-Waldenburg-Schillingsfürst (1897–1989).

Archduke Franz Salvator even took Stephanie with him to the Emperor’s hunting estate near Ischl, where she shot her first stag. She was entranced by the beauty of the mountain landscape, and learned that it was there that the old emperor spent the happiest hours of his life, surrounded only by a few huntsmen. Stephanie also wrote enthusiastically about the imperial mansion in Ischl, a charming little town in the Salzkammergut lakeland. In her unpublished memoir she described in detail the spartan furnishing of the Emperor’s rooms. She noticed the prayer-stool and the desk with the photograph of his consort, Elisabeth, who in 1898 had been tragically stabbed to death in Geneva by a deranged anarchist. In front of it lay a few dried flowers and a little framed poem, which the Empress had given him on the day of their engagement.

Stephanie must have been to Ischl quite often. Yet whenever she stepped inside the imperial mansion she was unable to shake off an oppressive feeling; she could not forget the many blows that Fate had dealt to the Habsburg dynasty: the terrible death of the Empress, the tragic suicide of Crown Prince Rudolf after he had murdered the young Baroness Vetsera; the assassination in Sarajevo in 1914 of the heir to the throne, Franz Ferdinand and his consort, Countess Sophie. Stephanie only ever went to Ischl when the imperial family were absent.

During the First World War Archduke Franz Salvator, a general in the cavalry, served as Inspector-General of Medical Volunteers, in which capacity he ran an aid operation for prisoners-of-war in Russia. In 1916 he received an honorary doctorate from the faculty of medicine at Innsbruck University, and became Patron of the Austrian Red Cross and of the Union of Red Cross Societies in the lands under the Hungarian crown. It was not long before the Princess also took an interest in nursing work.

Soon after the birth of her son, Stephanie volunteered as a nurse and received her basic training in Vienna. After that she worked for three months as ‘Sister Michaela’ under the direction of the ‘melancholy beauty’, Archduchess Maria Theresa, who was a very popular member of the Austrian royal family. Stephanie claims that it was through the Archduchess that she first met Franz Salvator, the old Emperor’s son-in-law, and that this happened in the hospital in Vienna’s Hegelgasse. However, this account does not correspond with the known facts.

Working as a Red Cross nurse in Vienna became too tedious for Stephanie. She wanted to go to the Front, and Archduke Franz Salvator made arrangements for her to be posted there. She gives a vivid account of her experiences. She went first to the Russian Front, to a field hospital in Lvov, which then bore the German name of Lemberg. Stephanie’s sister Milla had also decided to work there as a Red Cross nurse. Stephanie travelled with her butler and her chambermaid, Louise Mainz. As if this was not enough to raise eyebrows, the rubber bath-tub she brought with her struck people as especially odd. For a nurse, admittedly, hygiene was very important. And in order to protect herself from the stench of ether and gangrenous flesh, Stephanie almost continuously smoked the Havana cigars that she had, with considerable foresight, brought in large quantities from Vienna. She did not last very long at the Front. The medical officer in charge of the field hospital, Dr Zuckerkandl, showed no great enthusiasm for his ‘nurse’. Stephanie described him as very nervous and irritable, though a brilliant physician.

In the middle of the First World War, on 21 November 1916, Emperor Franz Joseph died. Princess Stephanie drove to Vienna and wanted to mingle with the mourners at the Hofburg palace. However, she was not permitted to do so. Ironically, the new Emperor’s High Chamberlain, who denied her access to the palace, was also a Hohenlohe, Prince Konrad Maria Eusebius (1863–1918). So she had to content herself with the role of a spectator outside St Stephen’s Cathedral.

Stephanie was very moved by the sight of the young Emperor Karl and the Empress Zita, as they left St Stephen’s Cathedral, together with the Crown Prince, the little Archduke Otto, to the sound of a 41-gun salute and a carillon of bells. She was convinced that ‘each individual would have willingly given his heart, his blood, all he had, and laid it at the feet of the three young people, to help them carry their new, heavy burden and make a success of it’.

In Vienna Stephanie and Archduke Franz Salvator spent hours together in the park and zoo at Schönbrunn palace. Since at that time the park was not yet open to the public, the two could stroll there completely unobserved. But on one occasion there was a mishap: when Stephanie tried to feed a bear and stretched her hand through the bars, it bit one of her fingers. She was afraid she might develop blood-poisoning and wanted to have an anti-tetanus injection immediately. But who could drive them to a doctor? The Archduke’s hands were tied, since he had picked up Stephanie from her apartment in Hofgartenstrasse in a coach with gilded wheels, which was reserved exclusively for members of the royal family. There would have been a scandal if the public had found out that, while the court was in mourning, the Archduke has been strolling with his mistress in the royal zoological park. He therefore took her to the nearest tram-stop, so that she could go to the doctor on her own.

Her friendship with the Archduke continued to mean a great deal to Stephanie. It was ‘genuine and heartfelt, a friendship that could only be ended by death’, as Stephanie summed it up in 1940, a year after Franz Salvator died.

Her next assignment as a Red Cross nurse was with the Austrian army, on its way to fight the Italians at the battle of the Isonzo river, in 1917. As the Austrian troops were advancing exceptionally fast, many comic situations arose. The ditches were filled with large cheeses, wine barrels and other things that the soldiers had looted, intending to send them home, but which were now being thrown away.

Stephanie recounted that, after the capture of Udine, soldiers had shot holes in the wine casks, got very drunk and nearly drowned. Most of them had poured vast amounts of wine into empty stomachs, often fell senseless and then lay in the wine flowing from the bullet-riddled barrels. She felt that many soldiers behaved quite atrociously in the occupied territories. But it was not just the common soldiery who went on these rampages; officers also helped themselves generously. Stephanie believed she might have done the same herself and was only restrained by her timidity, not by any high ideals. ‘All our officers took whatever they wanted.’ Count Karl Wurmbrandt-Stupach, one of her Red Cross friends, apparently despatched wagon-loads of fine glassware and antiques from Italy back to Vienna. She herself became the owner of the bed in which Napoleon slept at Campo Formio, after signing the peace treaty there a century earlier. However, she had not stolen the bed, but bought it from a starving farmer.

In the region around Tolmezzo, where Stephanie was working in the hospital, the local inhabitants were very short of food. People often came to the hospital and offered beautiful hand-woven linen in exchange for sugar, salt and bread, and so the doctors and nurses later returned home laden with valuable items.

Stephanie was in the town of Görz (now Gorízia in Italy) shortly after it was captured. All the houses had been destroyed and the surrounding forest completely burned down. The townspeople had fled and were living in little huts in the mountains or huddling in the abandoned trenches.

In all her spells of duty in the different field-hospitals Stephanie got on best with patients from the Tirol, from Hungary and Russia. They could stand pain and were very courteous. She thought that the Czechs and the Viennese were the worst – always moaning, always complaining, never satisfied – at least that was her experience of them.

Stephanie spent some time in Friuli, the Italian region bordering what is now Slovenia. She witnessed Austria’s defeat on the River Piave, in a battle that raged from 15 to 24 June 1918, when the Italians took their revenge for their humiliation at Caporetto. The princess had long ago become convinced that this war could not be won. ‘But when she tried to talk to her friends about her disillusionment, she was accused of defeatism’, her son Franz writes.

The situation at the Front had deteriorated seriously. There was nothing to eat, either in the hospitals or for the fighting troops. Morale was far from good. Then one day Stephanie received an urgent order to leave the war-zone. All the wounded able to travel were sent back to their home countries, and there was less for the nurses to do. Stephanie set off from Trieste back to Vienna. The journey of about 250 miles took her three days and nights.

In midsummer 1918 the princess moved with her son for a time to Grado, a resort on the Adriatic that was then still in Austrian territory and which, in the final months of the war, was a pleasanter place to be than Vienna. The armistice on 11 November 1918, which had rapidly followed the abdication of the German Kaiser, also meant the break-up of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

The socially unequal marriage between Stephanie and Prince Friedrich Franz von Hohenlohe came to an end in 1920. On 29 July of that year their divorce was formalised in Budapest. Friedrich Franz made it very clear that he wished a separation from his wife. What greatly annoyed Stephanie was the fact that only six months later he remarried, although he had sworn to her that there was no question of him marrying again. It was on 6 December 1920 that the Countess Emanuela Batthány (1883–1964), who had left her husband and three children, became Prince Friedrich Franz’s second wife.

One of the chapters in Stephanie’s memoir is entitled ‘Europe between the Wars’. She makes no secret of having greatly enjoyed the 1920s. She was now free to do or not do whatever she chose. As she explains, in Austria under its first republic, just as in Germany’s Weimar Republic, there was a great pursuit of pleasure, especially among the rich. And yet Stephanie was well aware of the political difficulties in Germany which, having lost the war that it started, was saddled with massive reparations and – as she put it – ‘robbed Peter to pay Paul’ by printing money and devaluing its currency in order to make these payments. She also observed with great anxiety the chaos into which the Balkan states, in particular, were descending.

In Vienna she sensed serious social unrest and thought to herself: ‘What could we, and what especially can I, as a woman, do about all this?’ She gave her own answer: ‘Nothing, except entertain the tired diplomats and ministers, in whose overburdened laps these responsibilities lie. They always like to chat with a woman after a hard day signing treaties.’ In Vienna Stephanie was among the chosen circle around Frau Sacher, the proprietress of the Hotel Sacher, which still exists today. She spent much of her time there making new friendships and cultivating them in discreet private dining-rooms. But it was also on the golf-course and in hunting-parties that she got to know rich and usually aristocratic men.

At the time the princess was certainly not aware that the contacts she made in those turbulent and pleasure-seeking days would one day be of incalculable value to her. But in retrospect she confirmed that ‘they provided me with a “passport” that could open any door for me, and later that is just what happened’.

The stories that Stephanie planned to write about the international high society in which she moved would, as she herself admitted, have been extremely amusing but also pretty revealing about a number of personalities in the public eye. Her anecdotes would to a degree reflect what people in those high positions said and thought.

Stephanie then produces a list of people who, in those ‘peacetime years’ and later on, played a part in her life: the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, the Aga Khan, Lloyd George, Clemenceau, Popes Pius XI and Pius XII, Arturo Toscanini, Lady Cunard, Sir Thomas Beecham, King Gustav of Sweden, King Manuel of Portugal, Sir Malcolm Sargent, Lord Rothschild, Leopold Stokowski, Admiral Horthy (the Regent of Hungary), Neville Chamberlain, Geoffrey Dawson (editor of The Times), the journalist Wickham Steed, Fritz Kreisler, Lady Londonderry, the Maharaja of Baroda, Margot Asquith, Lord Brocket and Lord Carisbrooke.

The princess’s drawing room in Vienna was frequented by many friends and admirers. As her son repeatedly assures us, she received a steady series of marriage proposals, but she wanted to go on living a life without attachments. One of her many admirers was George de Woré, the Greek Consul-General in Vienna. He came from an extremely wealthy Athenian family and his real name was Anastasios Damianos Vorres. He offered her the kind of life she liked. All year round they travelled together from one end of Europe to the other, and at no time did Stephanie have to worry about money.

Then along came a rich American, John Murton Gundy, followed in turn by a married millionaire named Bernstiehl, her ‘devoted slave’, who lavished gifts on her.

Yet Stephanie began to realise more and more that the war had robbed Vienna of its sparkle, that the end of the monarchy had brought many changes, and that now, when she went with some rich, influential galant to her much-loved Hotel Sacher, she felt she was being watched.

The threat of inflation was very much in the air. And being the clever woman she was, she decided in 1922 to leave Austria. She managed quite quickly to find a buyer for her apartment, along with all her furniture, porcelain, and cars. Her son describes the sum she received for them as ‘astronomical’. However, she did not pay the money into a bank account. Instead, she stuffed the notes into several suitcases and headed for Paris. But then, at the last minute, probably because of the cold winter weather – it was just before Christmas – she decided to take a train to Nice. Needless to say, she did not travel alone. With her were her son Franzi and his nanny, a maid, a butler, her sister Milla, and her friends Ferdinand Wurmbrandt, Karl Habig, and Count and Countess Nyári.

When they arrived in Nice, the party poured out from the wagon-lit, quickly followed by several dogs and any number of trunks and suitcases. After she had rented a villa at 123 promenade des Anglais, she acquired a motor-car, with one object in mind – to make a splash: it was a yellow Chenard & Walker tourer with a shiny silver bonnet and a second windscreen for the rear seats.

Stephanie lived life to the full. She was a frequent visitor to the casino – once, as her son tells us, ‘with no brassière under her transparent muslin dress’.

Among her friends were many Russians who had fled from the Revolution and were now living in the south of France. Many of them were grand dukes, and Stephanie had an intense flirtation with Grand Duke Dimitri. His name was also romantically linked with that of Coco Chanel, founder of the famous fashion house. Both she and Stephanie were also on close terms with the Duke of Westminster, who invited Stephanie to go fishing with him in Scotland. There she was attended by a Scots ghillie and had to spend hours practising her casts. She did not see the Duke until the evening, and after a week’s rather solitary stay in the wilds of the Highlands she graciously declined his proposal of marriage. She passed him on to Coco Chanel, who did not marry him either.5

A very long and ‘rewarding’, in other words lucrative, relationship then developed with John Warden, an American from Philadelphia. He initiated her into the financial mysteries of the stock market, where she became very successful. For more than ten years Warden worshipped her; then he married a young Polish woman, who soon afterwards became an extremely rich widow.

In autumn 1925 the princess set herself up in a Paris apartment at 45 avenue Georges V, in the exclusive 8th arrondissement. At that time the household employed a staff of nine. Living in the same building was a British insurance tycoon, Sir William Garthwaite. Sir William and the lady from Vienna became close, and he frequently helped her out when she was financially embarrassed. On one occasion, when she claimed to have been robbed of everything in broad daylight, Garthwaite took up the case on her behalf and after several years of dispute her insurers made good the ‘loss’.

The following episode is also worth mentioning. Stephanie loved dogs; her favourite was a Skye terrier, whose sire had been a present from her early admirer Rudolf Colloredo-Mannsfeld. When Stephanie’s butler was taking her terrier for a walk in the park, a man came up to them and said he was interested in just such an animal. He was Michel Clemenceau, son of the indomitable former prime minister of France, Georges ‘Tiger’ Clemenceau (1841–1929). Michel was looking for a pet for his old father and immediately went to introduce himself to Stephanie; he was bowled over by her and wanted to marry her. She preferred to keep the relationship on an informal level, but it lasted for several years nevertheless.

From time to time Stephanie von Hohenlohe lived in Monte Carlo, but the city soon seemed to her ‘as dreary as stale water’. She preferred Cannes. There she met François André, who had risen from being an undertaker’s assistant to a leading owner of luxury hotels. He also owned the casino in Cannes, where Stephanie won and lost large sums.

She also liked to spend the summer season in Deauville, the fashionable resort on the Channel coast of Normandy. There she met the multi-millionaire Solly Joel, principal shareholder of the South African diamond company, De Beers Consolidated Mines.

The summer of 1928 was taken up with a tour of Europe in the pleasant company of Kathleen Vanderbilt and her husband, Harry Cushing Sr, as well as Robert Strauss-Huppé, later the US ambassador in Colombo, Brussels and Stockholm, and a number of other upper-crust Americans.

For a variety of reasons, the year 1932 saw a major change of direction in Stephanie’s life. For one thing she had a road accident while being driven to Trieste by her chauffeur, Mostny. The car was a write-off. So the princess made her own way to Trieste and took the next fast train back to Paris. It was on that journey that she met a good-looking American banker, Captain Donald Malcolm, and for a time the two were inseparable. The greatest change, however, was that the princess found a highly paid political job working for the London newspaper publisher Lord Rothermere, whom she had known since 1925.

CHAPTER TWO

A MISSION FOR LORD ROTHERMERE

‘A number of people have written that from the outset I was determined to play an influential part in international politics. Nothing is further from the truth.’ We find this clarification at the beginning of the notes Stephanie jotted down in the form of short headings for the benefit of her ghost writer Rudolf Kommer. Her political activity did not start until she was retained by the British press baron, Harold Sydney Harmsworth (1868–1940) who, in 1913, was elevated to the peerage as Lord Rothermere. The first time Stephanie met him was in Monte Carlo in 1925. He was a very well known figure on the Côte d’Azur; his power, wealth and influence were common knowledge. He was a passionate gambler and it was in the Monte Carlo Sporting Club that she came across him, surrounded as always by toadies and hangers-on. He invited her to a drink and from that developed a relationship that would last thirteen years.

However, there is another version: that the introduction came about through James Kruze, an employee of his company, whose wife Annabel was a former mistress of Rothermere. However, it is not impossible that the 60-year-old Englishman and the 34-year-old Viennese princess could have got to know each other at the gaming-tables in Monte Carlo. Lord Rothermere was having a run of bad luck and Stephanie, who was playing next to him, helped him out with 40,000 francs. It appears that in return she was given some shares in his newspaper concern.

At any rate, after their first drink together, Lord Rothermere invited Princess Stephanie to his villa, La Dragonière, in Cap Martin. Though the princess may have hoped for another conquest, for the moment Rothermere only wanted to talk business.

Harold Rothermere was married, but his wife Mary had left him soon after the end of the First World War, preferring a life of freedom in France where she mixed with literati like André Gide.

Rothermere himself lived very modestly but had one weakness – attractive young women. Since he was a friend of the Russian ballet director, Sergei Diaghilev, until the latter’s death in 1929, he often romped around with ballerinas or put on evening performances at one of his magnificent residences, featuring the leading dancers of the day.

Rothermere was the younger brother of Alfred Harmsworth who, as Lord Northcliffe, became famous as the owner of the Daily Mail before and during the First World War. In the years of Germany’s postwar Weimar Republic, Northcliffe became one of Germany’s harshest adversaries and a strong supporter of France’s position. After Northcliffe’s death in 1922, his brother took over full responsibility for the press empire that included the Daily Mail, Daily Mirror, Evening News, Sunday Pictorial and Sunday Dispatch.

In the summer of 1927 Stephanie was staying with Lord Rothermere in Monte Carlo. She ran into a journalist who was desperate for a story for his paper. Stephanie mentioned in an offhand way that it might be a good idea if he wrote about the situation in Hungary. Rothermere, who was present, was very intrigued and asked Stephanie to ‘enlighten’ him on the subject. First of all a large map of Central Europe was purchased, on which Stephanie showed him Hungary, within its diminished post-1918 frontiers. In her memoirs the princess asks herself the question whether her heart would have beaten so strongly for Hungary, had she not, by marriage, become a member of the Hungarian branch of an aristocratic Austro-German family. ‘Would I have acted for Czechoslovakia, if I had married a Prince Lobkowitz instead of a Prince Hohenlohe?’ In the end, she explained her interest in Hungary by her love of its people and stressed that at the time she had no political motives whatsoever.

Stephanie suggested that the Hungarian ambassador in London, Baron Rubido-Zichy, should be invited to Paris to hold talks about the restoration of the monarchy in Hungary. But the ambassador declined. Lord Rothermere now launched a campaign in his papers in favour of revising the terms that had been imposed on Hungary in the Treaty of Trianon, which was signed in parallel with the Treaty of Versailles. In his Daily Mail on 21 June 1927 he published an article under the headline, ‘Hungary’s place in the sun’. Not just the title, but the whole article, had been written by the princess, and proved an incredible success; the editorial offices received 2,000 readers’ letters in one day.

Prominent Hungarians got in touch with Rothermere, and an extravagant programme for the restoration of the Hungarian monarchy was launched. A group of active monarchists even offered the crown of Hungary to Lord Rothermere himself, an idea that for a moment he took seriously. He soon had second thoughts, however, and put forward his son Esmond in his place, as a candidate for the vacant throne. All this greatly annoyed the princess, since she had been wondering whether her own son, though his Esterházy connections, might not be able to become King of Hungary.

In 1928 the Hungarian parliament passed a resolution officially expressing the thanks of the Hungarian people to the British peer. The University of Szeged offered him an honorary doctorate ‘for his selfless efforts in the Hungarian cause’. However, Princess Stephanie advised him rather to send his son Esmond to Hungary, so that the people there might get to know him. Esmond was duly welcomed with great enthusiasm and even received a solemn blessing from the Primate of Hungary, Cardinal Serédi. On his father’s behalf he accepted a hand-built motor-car, whose chassis was made from reinforced silver and the radiator covered in pure beaten gold.

However, it is important to note that neither the prime minister of the day, Count Bethlen – who still championed a Habsburg succession to the throne – nor the Regent of Hungary, Admiral Horthy, who was nurturing secret plans for a dynasty of his own, paid any attention to the Ruritanian events surrounding the young Englishman. Even the British government warned the Hungarians against dealing with Lord Rothermere.

In 1932, Stephanie’s position in France was becoming increasingly uncomfortable. The French government did not want anyone ‘messing around with the Little Entente’.1 There were rumours that the princess was the driving force behind the Hungarian campaign which was filling the newspapers. The Review of Reviews demonstrated clearly how she had set the entire operation in motion. She was put under official pressure to give up her activities with Rothermere. The press baron himself made no comment. Stephanie was even being accused of espionage, so she promptly quit Paris and moved with her mother and her dogs to London.

If we read the unpublished memoirs of the former Berlin journalist, Bella Fromm, they shed new light on Princess Stephanie’s time in Paris.2 Fromm insists that in 1932 Stephanie was expelled from France because of her espionage activities. For quite some time she had been in touch with Otto Abetz,3 a German who was in France working for better understanding between the two nations. At that time Abetz was not yet a member of the Nazi Party and had no inkling that one day he would be Hitler’s ambassador to Vichy France. A memorandum concerning Princess Stephanie circulated by the US government on 28 October 1941 also mentions her expulsion from France on the grounds of espionage.

Even before she left Paris in 1932, Stephanie was seriously short of money, since not even the occasional gifts of money or jewellery from Lord Rothermere were enough to maintain her extravagant lifestyle. So at the beginning of 1932 she had to ask Rothermere for a loan of £1,000. He did not give it to her.

However, Captain Donald Malcolm, who had lost part of his fortune in the Wall Street Crash of 1929, had moved to London, near the princess, and offered his services as her financial adviser. He advised Stephanie to negotiate a contract with Rothermere under which she would be employed as a society columnist. Malcolm drew up the contract himself, and Rothermere signed it on 27 July 1932. It was to run initially for three years, but he later renewed it for a further three. Her annual income was to be the not inconsiderable sum of £5,000 (about £125,000 in today’s terms). But that was just her retainer. For every assignment completed she would receive a further £2,000 (£50,000). This contract remained in force until early 1938, by which time the princess had collected well over £1 million in today’s money.

In London, the exclusive Dorchester hotel was being managed by the former director of the Hôtel du Palais in Biarritz. He offered the princess accommodation at the Dorchester at a reduced rent, because he thought her aristocratic credentials would further enhance the hotel’s reputation. However, after a short stay there, she decided to move into a private apartment of her own.

Now that Stephanie von Hohenlohe was on the payroll of an influential newspaper publisher, a completely new life opened up for her. Her first assignment, in August 1932, took her to the country estate of Steenokkerzeel in Belgium, where the ex-empress Zita, widow of Karl, the last Austro-Hungarian emperor, was living with her children. For the journey she was about to undertake, Stephanie asked Rothermere to have a Rolls-Royce painted for her in black and yellow, the colours of the Habsburg coat of arms. The princess’s task was to give the former empress more details about Lord Rothermere’s plans in the cause of Hungary and at the same time to offer her an annual pension.