Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

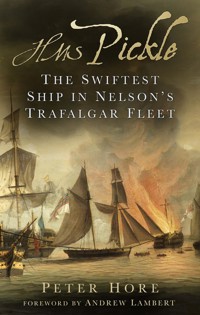

The curiously named HMS Pickle was the second-smallest British ship in Nelson's fleet at the Battle of Trafalgar. She acquired enduring fame, however, as the ship that carried Lord Collingwood's dispatch announcing the death, in the midst of battle, of Nelson. A topsail schooner and deemed too small to take part in the line of battle, Pickle and ships like it were essential in the transmission of communication. Relaying messages between admiral and Admiralty, the rapid movement of these ships pioneered an early worldwide web of information that helped secure a British victory over Napoleon. In this revised and updated edition, Captain Peter Hore describes the Pickle's beginnings as a civilian vessel, her arming for naval use and the pivotal role she played in Admiral Cornwallis's inshore squadron keeping watch over the French and Spanish. This full and captivating history narrates a colourful story of one small ship and the courage and resolution of her determined crew.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 258

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

About the Author

Peter Hore is an award-winning author and journalist. He served a full career in the Royal Navy, spent ten years working in the cinema and television industry, and is now a Daily Telegraph obituary writer and biographer. His other books include Nelson’s Band of Brothers and News of Nelson: John Lapenotiere’s Race from Trafalgar to London. He is a fellow of the Royal Historical Society, the Society for Nautical Research, and the Swedish Royal Society of Nautical Sciences.

Cover illustration: Robert Dodd 1793, © Bonhams Ltd.

First published 2015

This paperback edition first published 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Peter Hore, 2024

The right of Peter Hore to be identified as the Authorof this work has been asserted in accordance with theCopyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprintedor reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic,mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented,including photocopying and recording, or in any informationstorage or retrieval system, without the permission in writingfrom the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75096 659 7

Typesetting and origination by JCS Publishing Services Ltd

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

List of Illustrations

Foreword by Professor Andrew Lambert

Acknowledgements

1 Seymour’s Sting, 1799–1801

2 The First Pickle, 1800–4

3 A Bloody War and a Sickly Season

4 The Journey from Ilfracombe

5 Lapenotiere at the Helm, 1802–3

6 In a Pickle

7 Pickle at Work

8 Across the Pond, 1805

9 The Battle of Trafalgar

10 The Race to London

11 The Iphigenia Complex, 1806–8

12 Celebrating the Pickle

13 The Toast in Solemn Silence

Notes

Select Bibliography

List of Illustrations

Chart of the West Indies

First muster book of HMS Pickle – 21 March 1802

Account of Expenses of Lieut Lapenotiere

Map of the coast of Spain and Portugal

HMS Pickle – Ship’s Company at the Battle of Trafalgar – 21 October 1805

Celebrating Pickle Night

Pickle’s Record of Maintenance from the Admiralty ‘Progress Books’

HMS Pickle – Extract of the Muster Book when she ran onto the Chipiona Shoal, 26 July 1808

Plates

1 Vice-Admiral Lord Hugh Seymour

2 The Waldegrave Sisters

3 La Recouvrance

4 HMS Pickle sail plan and gun ports

5 The Loss of the Magnificent

6 Lapenotiere’s plan of Trafalgar

7 The Battle of Trafalgar

8 Jeanette, Trafalgar 1805

9 Trafalgar flyer

10 John Richards Lapenotiere

11 William Marsden

12 Spanish gunboat of the type which Pickle fought in July 1805

13 James Rowden’s medal

14 The fleet minesweeper, HMS Pickle

15 After-dinner speech at Pickle Night in New York

Foreword byProfessor Andrew Lambert

The schooner HMS Pickle acquired enduring fame as the ship which carried home Lord Collingwood’s immortal dispatch announcing the death of Nelson, amidst the triumph of Trafalgar, a celebrity reflecting the sublime bathos of the event. Yet, as Peter Hore demonstrates in this suitably sprightly life and times of the little ship, there was much more to the Pickle than that. Her story shifts the focus of naval warfare in the age of Nelson from great fleets, frigate actions and outsized heroes to the essence of sea power, the quiet connections that linked admirals to Admiralty, fleets to bases, and defeated the greatest of Napoleon’s schemes without firing a shot. Britain’s total dominance of maritime communications doomed the emperor’s plans long before Villeneuve and Gravina set sail from Cadiz. The rapid, efficient and above all intelligent movement of naval, diplomatic and commercial intelligence by sea, in ships like the Pickle, created a pre-modern worldwide web, and secured Britain, the empire, allies and trade. Swift, reliable intelligence flows changed the way wars were waged, and they gave the Admiralty an edge.

HMS Pickle may have been a trifling ship, armed with guns no bigger than a general’s boots, but she represented a system, and many more small craft. The men who commanded these little ships were seamen in the finest tradition; they had to get the mail through, at all costs, and at the highest speed. These were long, dangerous passages, generally under a full press of sail, officers and men soaked and exhausted by the demands of their task, the ship strained and worn. In command of the Pickle, Lieutenant John Richards Lapenotiere earned a reputation for speed and security that gave confidence to his superiors as discerning as Admirals Sir Cuthbert Collingwood and Sir William Cornwallis. He was also highly effective at conducting inshore reconnaissance, and his reports were trusted by Collingwood, that most demanding of taskmasters. Ultimately this service would earn him a long overdue promotion, along with a useful reward. It wore out his ship.

The names of commander and ship will be forever linked with the greatest day in naval history, examples of courage and resolution in the finest traditions of the Royal Navy. May their memory be honoured for as long as men still go down to the sea in ships.

Professor Andrew LambertLaughton Professor of Naval HistoryKing’s College, London

Acknowledgements

As a contribution to the celebration of the bicentenary of Trafalgar, I wrote News of Nelson: John Lapenotiere’s Race from Trafalgar to London, drawing on my own study of the life and times of John Lapenotiere and also on the late Derek Allen’s extensive research notes about HMS Pickle. In the two decades since then new information has come to light, and I have been able to undertake further research regarding Lapenotiere and Pickle. So, when first Michael Leventhal and second Chrissy McMorris suggested a reprise of News of Nelson, I welcomed the opportunity.

In this second version, I am grateful to Lindy MacKie for continued access to Derek’s notes, and I wish to record my thanks to Derek for his painstakingly accurate, thorough notes on many aspects of the life of HMS Pickle (1801–8). On every occasion when I have read the sources which Derek studied and transcribed up to his death in 2003, I have found his work detailed, comprehensive and faultless, and I readily acknowledge the excellence of his work and the huge debt which I owe.

For new information, for help in furthering my research, for their kindness in sharing their expertise and in resolving otherwise intractable problems and for their comments and advice, I wish to express my warmest thanks to: Dr Charlotte Andrews of the St George’s Foundation, Bermuda; Captain Sally McElwreath Callo, USN of the American Friends of the National Museum of the Royal Navy; Anthony Cross, Warwick Leadlay Gallery, Greenwich, London; Dr Michael Crumplin, author and medical practitioner; Michael Dennis, descendant of George Almy and genealogist of the Almy family; Dr Edward Harris, Jane Downing and Elena Strong of the National Museum of Bermuda; Agustín Guimerá, Instituto de Historia, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Madrid; Professor Barry Gough, Professor Emeritus, Wilfrid Laurier University in Waterloo, Ontario; Professor John Hattendorf; Ernest J. King, Professor of Maritime History at the United States Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island; Clifford Jones, Old Blue and museum volunteer at Christ’s Hospital, Horsham, West Sussex; Michael Nash of Marine and Cannon Books; Bob O’Hara, independent researcher at The National Archives, Kew; Captain John Rodgaard, USN, author and fellow time-traveller; Carmen Torres, Museo Naval, Madrid; and the staff and volunteers of the Warwickshire County Record Office, of The National Archives, Kew, and of the Caird Library, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich.

No study of the British Navy at the apogee of its success in the Great War of 1792–1815 can be complete without reference to the decades-long studies which have been undertaken by Patrick Marioné to produce his Complete Navy List of the Napoleonic War and Pam and Derek Ayshford’s Ayshford Trafalgar Roll. I am especially grateful to Patrick for making these databases available to me and for his permission to quote freely from News of Nelson, which he published in 2005.

No book is possible without a first-class editorial team, and I should like to thank the anonymous reader, designer Martin Latham and the editor Chrissy McMorris at The History Press.

All errors of commission and omission are mine and mine alone.

Peter HoreIping, West SussexJuly 2024

1

Seymour’s Sting, 1799–1801

The Sting was ‘a clever, fast-sailing schooner of about 125 tons’ which would become better known as HMS Pickle, the ship that brought the news of the British victory at the Battle of Trafalgar, and of the death of Nelson; she was bought for the Royal Navy in December 1800 by Vice-Admiral Lord Hugh Seymour, the Commander-in-Chief at Jamaica.

Tom-Tit Cruisers

According to Steel’s Elements of Mastmaking, Sailmaking and Rigging, published in 1794, a schooner was:

A small vessel with two masts and a bowsprit. The masts rake aft, but the bowsprit lies nearly horizontal. On the bowsprit are set two or three jibs; on the foremast a square foresail; and, abaft the foremast, a gaff or boom-sail; and above those a topsail. Abaft the main-mast is set a boom sail, and above it a topsail. The main-stay leads through a block, at the head of the foremast, and sets up upon deck by a tackle. By these means, the sail abaft the foremast is not obstructed when the vessel goes about, as the peek [sic] passes under the stay. Schooners sail very near the wind, and require few hands to work them. Their rigging is light, similar to a ketch’s, and the topmasts fix in iron rings, abaft the lower mast-heads.1

At the beginning of the Great War of 1792–1815 the schooner as a type was new to the Royal Navy, and naval officers were sceptical of their design. In the 1760s the Navy had purchased some schooners in New England, where they were useful against smugglers and privateers, but in Europe the rig was not regarded as suitable for serious fighting vessels. Square sails could be backed, which made square riggers handier in battle, and their yards endowed some redundancy and thus resistance to battle damage, whereas the loss of a boom would render a schooner unmanageable.

In 1796 two two-masted sloops of 400 tons, Dasher and Driver, were built in Bermuda for the Royal Navy, but the fore-and-aft rig was not well established in Britain before 1800. Then two new schooners, Express and Advice were introduced; at 88ft long and 178 tons, with a crew of thirty and armed with six 12-pounder guns, they were designed for speed but proved unsuccessful. Next, a new schooner design was produced by a commercial builder in Bermuda. The model for what became the Ballahou class was the Virginia pilot boat Swift of 1794: they were of 54ft length and 72 tons, had a crew of twenty and carried four to six guns. Armed, however, with 12-pounder carronades, they were much criticised; William James called them ‘tom-tit cruisers’ and he excoriated the schooner.2 Others pointed to their poor survival rate: of the seventeen Bermudabuilt Ballahou-class and twelve Bird-class schooners built in England, all but eight were wrecked or captured. In 1806 the Admiralty’s Bird class in particular was criticised by Admiral the Earl of St Vincent, when Commander-in-Chief in the Channel, who called them ‘a plague and burthen to all who have them under their orders’, and they were, he wrote, ‘no more like Bermudian vessels than they are like Indian prows’. What naval officers wanted were fast ships, he wrote, ‘similar to a Bermudian despatch boat’.3

Naval officers did not want the bastardised designs produced by the Admiralty, and, while the Admiralty was building faux schooners, the fleet was capturing real ones. By the end of the eighteenth century there were some dozen American and French schooners in the Royal Navy; soon Sting would join them.

There is no proof, but probably the first Pickle (1800–4) and Sting, which became the second Pickle (1801–8), were both built in Bermuda, though the name Sting has suggested to some writers that she may have been American-owned. Since the seventeenth century there had been a shipbuilding industry on Bermuda, with ships built of the indigenous cedar tree, juniperus Bermudiana, which once covered the islands at a density of 500 trees to the acre. During the seventeen and eighteenth centuries islanders had developed light, two-masted ships which excelled at sailing close to windward. Working by trial and error, Bermudians experimented with using the rigs of other Atlantic vessels and invented the triangular sail or Bermuda rig. They also changed the hull form and adjusted the rigging. The hulls had sharp bows and fine lines which minimised drag and made less leeway. Bermudian sloops and schooners also carried huge mainsails on long booms, the masts were raked backwards, and the bowsprits raised so that they would not be buried in head seas when under full sail. The sails included jibs, spritsails, staysails (or trysails), ringtails, square topsails and stunsails (or studding sails). Their frames and planking below the waterline were made of Bermudian cedar, which was light in density and – being resistant to rot and worm – was regarded as the best shipbuilding timber. Better still, the local cedar grew from seed to usable size in only twenty to thirty years and did not require seasoning. Other woods, including mahogany, were imported from Central America for keels, and white pine and oak came from North America for masts, spars and decks. The fine lines of Bermudian sloops and schooners reduced the ’tweendecks space available for cargo, and, to save weight, Bermudian skippers dispensed with guns and relied on speed to escape any pursuer.4

Two Pickles

Little is known accurately about the appearance of the first Pickle, but there are two contemporary paintings of the second ship of the name. Robert Dodd and his brother Ralph lived and worked in Wapping, London, where their marine pictures were admired as much for their ability to capture the atmosphere of battle and storm as for their technical accuracy. Robert Dodd moved to 41 Charing Cross Road (now Whitehall), which he advertised as being ‘six doors from the Admiralty’. Naval officers after visiting the Admiralty used to call on Dodd to commission or buy from him pictures of their ships, or perhaps to sell information to him. This apparently is what HMS Pickle’s commander, John Richards Lapenotiere, did in November 1805 after he had delivered Collingwood’s dispatches, enabling Dodd to scoop the first paintings of the battle and the victory off Cape Trafalgar. One of a pair of watercolours painted in November 1805, and sold at Bonham’s in 2003, clearly shows Pickle standing by the burning French ship Achille. The appearance of Pickle fits Steel’s description, but if Dodd used Steel as a crib, he presumably also had Lapenotiere leaning over his shoulder to remind him of what she actually looked like.

Other officers returning from Trafalgar had their views of how the battle had developed and wished to contribute their knowledge, and, early in 1806, Dodd altered his original watercolours and turned them into a set of four engravings. The second picture of the second pair, The Victory of Trafalgar, shows a smoke-shrouded melee about 4.30 p.m. on 21 October; the French van is escaping but Pickle, diminutive compared to the ships of the line, is shown on the edge of the picture.5

The second near-contemporary picture of Pickle has only recently been identified. The Scots-born John Christian Schetky was, successively, drawing master at the Royal Military College at Great Marlow, professor of drawing at the Royal Naval Academy, Portsmouth and at the East India College, Addiscombe. George IV made him Marine Painter in Ordinary in 1820 and Queen Victoria confirmed this title in 1844. Again Schetky had an eye for composition as well as a reputation for technical accuracy. He painted many ship portraits and reconstructions of sea battles from the age of Nelson, including the Loss of the Magnificent, 25 March 1804 – and on the extreme right of this picture is Pickle, assisting in the rescue of the crew.6

Just a little more is known about Pickle from the occasional draught marks entered in her master’s log. For example, an entry in her master’s log for 21 February 1802 notes that her draught forward was 7ft 7in (2.3m) and aft was 11ft 7in (3.5m). The dimensions usually given for Pickle are length on gun deck of 73ft 0in (22.25m), length of keel for tonnage 56ft 3¾in (17m), breadth 20ft 7¼in (6m), depth in hold 9ft 6in (2.8m) and tonnage 127 tons. An examination of her several master’s logs confirms the suite of sails which she carried. It is important to remember that although Sting, later Pickle II, was pierced for fourteen guns and is frequently described as such in contemporary literature, she did not carry more than ten guns, and that even then she was top heavy; one of Lapenotiere’s first orders after he took command in 1802 was to place four of these guns in the hold to improve stability and sailing performance.

Lord Hugh Seymour

Lord Hugh Seymour first chartered Sting at the rate of £10 per day to augment his fleet in the West Indies. Seymour, who had been appointed Commander-in-Chief at Jamaica on 9 May 1800 and had arrived at Jamaica in August that year to take up his command, was the scion of a noble house. Though a contemporary of Nelson, he was never one of Nelson’s fabulous band of brothers. Indeed, the two men were as unalike as it were possible to be: whereas Nelson was a poor parson’s son from Norfolk and the single spark in all the generations of his name, Seymour’s family held honours and office from the Norman Conquest to the present day, and Diana, Princess of Wales, was one of Hugh Seymour’s direct descendants.7

Hugh Seymour Conway (he dropped the second name after his father’s death in 1794) was born on 29 April 1759 and was educated at the Rev. Thomas Bracken’s Academy in Greenwich.8 While Seymour was at Bracken’s his name was also entered as a captain’s servant in the yacht William and Mary, though it is unlikely that Seymour went to sea until sometime later, when he was rated midshipman by a distant kinsman, Captain John Leveson-Gower, in the 32-gun frigate Pearl in about 1771.9 By coincidence, John Richards Lapenotiere, one of Pickle’s future commanders, also claimed Leveson-Gower as a patron.

Seymour rose quickly – more quickly than Nelson – and if some of his early rise was due to his privileged birth, talent too played a large part in his promotion. He took part with some distinction in the American War of Independence, at the Relief of Gibraltar in 1782, and, while Nelson fretted ashore and unemployed during the peace between the American and French wars, Seymour was recalled in 1790 during the Nootka Crisis or Spanish Armament to command the 74-gun Canada, though his service was interrupted when he was hit on the head by an unlucky cast of the leadsman.

The only recorded occasion on which Seymour and Nelson met was when Seymour was on his way to England with dispatches after the Siege of Toulon in 1793. After a long convalescence from the blow to his head, in August 1793 Seymour, in the frigate Tartar, met Nelson in Agamemnon and told him of the surrender of the port and of the French fleet. Nelson wrote a perfectly boring letter to repeat the news to Frances (Fanny), his wife: ‘I sent you a line by Lord Conway [i.e. Seymour] who is gone home with Lord Hood’s despatches.’10 The next time Nelson would mention Seymour in his correspondence was when in November 1795 he was agonising whether to stand as an MP, and he reckoned that ‘Lord Conway is my friend and acquaintance, and a more honourable man, I am confident, does not grace the Navy of England’.11 However, Nelson’s use of the name of Conway rather than Seymour indicates that Lord Hugh was not a close acquaintance.

Seymour took a prominent part in the Battle of the Glorious First of June, 1794 and was praised by Howe for his part in breaking through the enemy’s line on the second day of the battle. Among the captured French ships on 1 June 1794 was the 80-gun Sans Pareil, a ship whose lines British shipwrights would subsequently copy. Seymour commanded her as captain and when he was made rear-admiral in 1795 he kept her as his flagship. In 1797 Seymour commanded a squadron of four sail of the line and two frigates, which was sent out to search for a Spanish treasure fleet, causing Nelson to complain to the Duke of Clarence, ‘we find that a squadron under Lord Hugh Seymour is actually cruising on our station’.12 Jealous that Seymour might take the prize money which Nelson himself so lusted after, Nelson wrote to Fanny, and to anyone else who would listen, ‘I hear that a squadron is looking out … for the galleons daily expected.’13

In 1795 Seymour had become a member of the Board of Admiralty. There he is credited with having added epaulettes to officers’ uniforms: while serving ashore during the Siege of Toulon and on liaison duty with French royalists he found that in his plain and unadorned uniform he had some difficulty in impressing his rank upon the French, and so he regularised the wearing of epaulettes, which had already become a fashion among British officers.

Seymour received a salary from his appointment to the Admiralty, and his summer cruises were motivated by the desire to gain prize money. When he learned that Dutch interests in London were plotting to hand over the rich Dutch colony of Surinam in the Guianas, Seymour was quick to have himself appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Leeward Islands and to sail for the Americas, taking San Pareil as his flagship.14

That Hamilton Woman

Seymour had another Nelson connection. In 1783, in the lull between the American and French wars, Seymour, with his younger brother George and one John Willett Payne, known as Jacko, took a house in Conduit Street, where the three friends led an irregular and convivial life. Payne had already seduced a penniless 16-year-old girl called Amy Lyon who was newly arrived in town from Liverpool, and she had given birth to his daughter. Amy or Emily or Emma (she altered her name several times) was then living in Arlington Street on the edges of Mayfair, at the home of a notorious madam and was probably being groomed for a life of prostitution. She was saved from this fate when the red-blooded Lord Henry Featherstonehaugh took her as his mistress to his house, Uppark, on the South Downs.

During their time in Conduit Street, Payne and the Seymour brothers became close friends of George, Prince of Wales, and it was most likely at Conduit Street that ‘Prinny’ first saw Emma and his life-long lust for her was fired. The party at Conduit Street was, as a contemporary account put it, one long ‘well-remembered festivity, which during the course of a twelvemonth prevailed in this select and fashionable coterie which was suspended by the nuptials of Lord Hugh’.15 In 1785 Seymour married Lady Anne Horatia Waldegrave and the couple went to live at Hambleton, Hampshire.

While pursuing their naval careers, Hugh Seymour and John Willett Payne remained close friends of the prince, and Payne became his private secretary and the go-between for the prince and his mistresses. Payne negotiated the prince’s secret marriage to Maria Anne Fitzherbert, travelling to France – where the Catholic Mrs Fitzherbert had taken refuge from her royal suitor – and carrying an offer to set up a trust fund of a quarter of a million pounds sterling for Mrs Fitzherbert and any future children at the bank of his relative Rene Payne. The prince and Mrs Fitzherbert were married in secret on 15 December 1785 and began their married life under the alias of Mr Randolph and Mrs Ann Jane Payne. One of the trustees of the fund was Hugh Seymour.

Meanwhile, when Featherstonehaugh had finished with Emma he passed her on to his friend Charles Greville, and Greville, when he wanted to marry an heiress, in 1786 passed on the 21-year-old Emma to his uncle, Sir William Hamilton, the British ambassador at Naples. There she was waiting when Nelson brought his broken ships and his broken body after the Battle of Aboukir Bay in 1797, and Emma entered history as Nelson’s Lady Hamilton.

While at the Admiralty Seymour had been eager to seize for himself the appointment of Commander-in-Chief of the Leeward Islands and thus the opportunity to earn more prize money by taking the Dutch colonies in South America. On 31 July 1799 he sailed from Port Royal, Martinique (a British possession during most of the Great War) flying his flag in Prince of Wales (98).16 The other ships of his squadron included Invincible (74), several frigates and a force of troops under the command of a lieutenant-general. On 11 August Seymour’s expedition anchored in the mouth of the Surinam River, and after brief negotiations the Dutch governor capitulated and the garrison marched out ‘with the honours of war’. By 22 August several forts and posts, including the town of Paramaribo, the capital of the colony, ‘were taken quiet possession of, and the whole of Surinam surrendered to the arms of Great Britain’.17 The French corvette Le Hussard (20), and a Dutch brig, Kemphaan, renamed Camphaan (16), were added to the British Navy.18

The Beautiful Schooner

Next, Seymour succeeded Sir Hyde Parker in the lucrative appointment of Commander-in-Chief at Jamaica.19 This was the time of the fledging USA’s Quasi-War, an undeclared war fought with France, when American and British forces loosely collaborated. The American commodore, Thomas Truxton, penned a letter containing one of the earliest statements of the special relationship which has existed between the Royal Navy and the US Navy, writing to his officers that ‘a good understanding is highly necessary as we are acting in one common cause against a perfidious enemy’ – he meant the French – ‘and we should endeavour to cement our union by acts of kindness, civility and friendship to each other on all occasions for it is unquestionably our interest and their [the British] interest so to do.’ Truxton enclosed a copy of his letter to Hugh Seymour with his offer to cooperate against the common enemy.20 Their particular common enemy was the 48-gun French frigate Vengeance, which had been mauled in a fight with the USS Constellation. Vengeance was being hunted by both the Americans and the British, and in September 1800 Seymour sent Captain Frederick Watkins in the former French Nereide (38) to the Dutch island of Curaçao in search of her.21

While Watkins was at anchor off Curaçao a large American merchant ship, Eagle, ran alongside him. Nereide was herself a captured French frigate and apparently her French lines had deceived the American into thinking that she was the Vengeance, with which he had a rendezvous. Watkins ordered a search of the American and, when Nereide’s master, a Mr Raven, thrust his arm into a barrel of flour he brought up a handful of gunpowder. A further search revealed that under the barrels of gunpowder, which were only topped with flour, Eagle was carrying two mortars, a battering train, shells and shot for a siege.

The Dutch on the island were under attack by a French force which consisted largely of recently released slaves from the island of Guadeloupe. Threatened by an ill-disciplined force unaccustomed to the rules of war as exercised in Europe, the Dutch governor had appealed to Watkins for help: ‘We beg you to enter into this port as soon as possible,’ and separately the American merchants in Curaçao also requested Watkins’ protection.22

Watkins reported to Seymour that there were about a thousand French on the island itself, and ‘thirteen privateers of different descriptions which are very valuable having all the plunder of the place onboard’. ‘The governor’, reported Watkins, ‘is very anxious for your Lordship’s sending a force to take the island.’ In addition to the Eagle, which ‘I now send in [and which] had three thousand stand of arms and twenty tons of gunpowder onboard; I also captured a beautiful schooner which I keep as a tender’.23

This ‘beautiful schooner’ may have been Sting.

The Surrender of Curaçao

Watkins did not wait for a reply to his letters to Seymour, but on 11 September 1800 wrote again:

My Lord, I do not wish to lose a moment in sending a fast sailing vessel to inform your Lordship, that the island of Curaçoa has claimed the protection of his Britannic Majesty. I have in consequence felt it my duty to take possession of it in his name. I am now running for the harbour, as it is absolutely necessary to lose no time to save the island from the enemy, who threaten to storm the principal fort tonight; but I trust the Nereide’s assistance will be the means of frustrating the enemy’s views, and saving a most valuable colony for his Majesty. I compute the force of the French to be about 1500 now in possession of the west part of the island, but no strong post of any consequence to prevent my holding the forts commanding Amsterdam, until I am honoured with an answer from your Lordship. There is great property afloat belonging to the Spaniards. Lieutenant Paul will have the honour of delivering this dispatch to your Lordship, of whose exertions and zeal for the service I cannot speak in too strong terms.24

The French were commanded by a mulatto general, Benoit Joseph André Rigaud, and rather than surrender to Rigaud and be overrun and ravaged by freed slaves, the Dutch governor preferred to give up some £3 million sterling in public property, colonial produce and money to Watkins. Watkins landed the cannon taken in the American merchant ship and, joining the Dutch forces, drove the French across the island, where they took ship and retreated to Guadeloupe. Watkins told Seymour: ‘Sept 14. My Lord, Since my sending my last dispatch of the 11th instant, Governor Johan Rudolph Lauffer has finally surrendered the islands of Curaçoa and its dependencies to his Majesty’s arms. Enclosed I have the honour of transmitting to your Lordship a copy of the terms of capitulation.’25

American and British accounts of the capture of Curaçao differ, but according to Watkins, on 20 September two American sloops, Patapsco and Merrimack, landed twenty US marines, although there were only clearing operations to be undertaken.26