9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

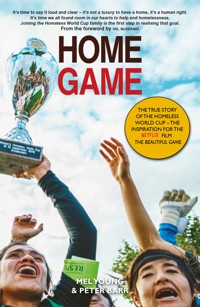

It's time to say it loud and clear – it's not a luxury to have a home, it's a human right. It's time we all found room in our hearts to help end homelessness. Joining the Homeless World Cup family is the first step in realising that goal. From the foreword by VAL McDERMID An estimated 100 million people worldwide are homeless and 1.6 billion live in sub-standard housing. But how can such a simple game like football tackle such a complex problem? Mel Young and Peter Barr tell the story of the 1.2 million homeless people from 70 countries who have taken part in the Homeless World Cup since it started in 2003. Home Game describes its profound impact on players, spectators and society at large – and how 'a ball can change the world'

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

MEL YOUNG is President and co-founder of the Homeless World Cup and is recognised as one of the world’s leading social entrepreneurs.

PETER BARR is a Trustee of the Homeless World Cup Foundation. He is a journalist with 40 years’ experience working in Hong Kong, Singapore and Scotland.

Homelessness does not respect any national borders. It can happen to anyone, anywhere at any time. It can happen to me and to you.

We all love football and we all hate homelessness – it’s a no brainer.

Irvine Welsh – Novelist and Ambassador for the Homeless World Cup

We have to unite against homelessness as we did when we fought apartheid.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu, speaking at the Homeless World Cup in Cape Town (2006)

I have seen how the Homeless World Cup really does inspire homeless people to change the direction of their lives.

Colin Farrell – Actor and Ambassador for the Homeless World Cup

Sport and football are very important, and that is why I decided to be an Ambassador for the Homeless World Cup. At first I was a bit sceptical, but I’ve seen the social impact, and I also see the impact in the eyes of the players. C’est magnifique!

Emmanuel Petit – Footballer and Ambassador for the Homeless World Cup

Football and the Homeless World Cup have the power to fire up a person to excel as a human being, to change their lives for the better. It is fantastic that football brings this opportunity to their lives.

Eric Cantona – Footballer and Ambassador for the Homeless World Cup

For seven days in July, George Square in the heart of the city will be the most inspiring place on the planet.

HRH The Duke of Cambridge, in a message to participants before the Homeless World Cup in Glasgow (2016)

The Homeless World Cup opened the door to success and gave me a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to make a change in my life and be part of something positive.

Lukes Mjoka – represented South Africa at the Homeless World Cup in Rio (2010) and coached the team in Paris (2011)

I realised that soccer was my freedom. After Rio, I had a new purpose in life. I saw how people loved the game and also the impact of the Homeless World Cup. That’s why I love the game, and think it’s the most powerful sport in the world.

Lisa Wrightsman – represented the USA at the Homeless World Cup in Rio (2010) and now coaches the USA women’s team

I am pleased to know that present at the conference are the founders of the Homeless World Cup and other foundations that, through sport, offer the most disadvantaged a possibility of integral human development.

Pope Francis – speaking at a conference about sports and faith in the Vatican (October 2015)

First published 2017

This edition 2024

ISBN: 978-1-80425-153-9

The authors’ right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

Typeset in 10.5 point Sabon by Lapiz

© Mel Young & Peter Barr 2017, 2024

For the players

Contents

Foreword by Val McDermid

Introduction

1Hold Your Breath Time – It’s the night before kick-off in Mexico City, 2012, but where’s the Ghana team?

2One Homeless Person is One Too Many – What can we do about homelessness?

3Homeless to Heroes – What is the impact of the Homeless World Cup?

4Something Magical Happened – How did it start?

5Why Soccer? – Because it’s The Beautiful Game

6From Russia With Hope – Which countries have the worst homelessness problem?

7From Chavos to Playboy – What’s a typical day at the Homeless World Cup?

8The Poverty Industry – You work with corporates. Are they not the cause of the problem?

9The Human Factor – Why do so many people get involved with the Homeless World Cup?

10What Do Homeless People Look Like? – ‘Most of the players do not look like homeless people.’

11The Story Continues – Highlights from Poland, Chile, Amsterdam and Glasgow

12Extra Time

Appendix – Homeless World Cup venues

Foreword by Val McDermid

2023 was a year of poignant celebration for the Homeless World Cup. Celebration, that after three years without a tournament because of covid, we were actually staging an international event in a superb stadium in Sacramento, California. Poignant because we still needed to. Because homelessness is still a worldwide scourge.

I live in Scotland, where the Homeless World Cup was established over twenty years ago. We’re a relatively prosperous country, part of the G7, virtually self-sufficient in power and water. And every week in Scotland, five homeless people die.

It’s a shameful admission.

Somehow, during the pandemic, homeless people were found accommodation off the streets. Throughout the UK, they were provided with places to sleep. But as soon as the immediate crisis was over, so was the assistance. Now the numbers are rising again, year on year, as the cost of living drives people over the edge of precarity into destitution. Year on year, more wasted lives.

I first came into direct contact with homeless people when I was a student. The Simon Community offered support from a narrowboat on the Oxford canal and I volunteered there. I don’t imagine I was much use except as a willing ear but the experience has stayed with me.

I was profoundly disturbed by the stories I heard from the men who came there for help; I couldn’t believe that in a country as rich as ours people could fall so comprehensively between the cracks. We had a social security system back in those days that let students sign on the dole during the holidays. How had it failed the men on the boat so comprehensively?

Their fate frightened me. It made me understand how fragile our grip on our lives can be. How easily the things we take for granted can slip from our grasp. But in those young and idealistic days, I thought this was a plague that would pass. That we would find a way to help those homeless people back into a community. A cure for their – and our – ills.

But still, fifty years on, homelessness is everywhere. No country is immune from it. Now, as the world wrestles with the aftermath of a pandemic, it’s even more clear how many lives are lived right on the edge.

I am one of the fortunate ones. I’ve never lacked a bed for the night. I’ve never had to go to bed hungry. I’ve always belonged to a tribe, usually several at a time. One of those tribes is football.

When I go to games, whether it’s a cup final or a Sunday afternoon women’s game in a snowstorm, I still feel part of that tribe. We recognise each other, whether or not we know each other’s names and histories. We nod acknowledgement, we exchange a few words, we have a laugh. We talk about our team’s prospects, we swap stories of past glories and ignominies. We belong. And belonging always brings us hope in the dark times.

For homeless people, there is little sense of belonging. And so, there is often little hope. Since the Homeless World Cup began, that has changed for many of the lives it has touched. Men and women have been brought together by street soccer. They’ve trained together and worked together to build something beyond themselves. They’ve met people like them from all over the world, and shared their stories, finding common ground, common dreams. For many of them, life after the tournament has changed forever. They’ve gone on to jobs, both inside and beyond sport. They’ve found their tribe. They have homes.

Wherever the tournament has been played, its impact has spread far beyond the pitch. Spectators have fallen in love with the spirit and courage of the players. Their stories have moved strangers who now see for themselves the humanity of the drama being played out before them and have taken away a fresh understanding, better equipped to help change the minds of others. Hope spreads like that.

Home Game outlines the journey so far of the Homeless World Cup. It’s an astonishing story of what can happen when people find the determination to build a change for the better. Its stories tell of heartbreak but also of hearts bursting with achievement. It demonstrates how a game can be a game-changer.

That progress and those achievements have provided inspiration beyond homelessness and beyond football. This year sees the release of a Netflix drama The Beautiful Game starring Bill Nighy, Micheal Ward and Valeria Golino. Written by acclaimed screenwriter Frank Cottrell-Boyce, it takes the viewer on the Homeless World Cup journey from isolation and despair to camaraderie and possibility. The more people see the film and the tournament, the harder it will be for the politicians to turn their backs on homeless people.

It’s time to say it loud and clear – it’s not a luxury to have a home, it’s a human right. It’s time we all found room in our hearts to help end homelessness. Joining the Homeless World Cup family is the first step in realising that goal.

Val McDermid

Val McDermid is an internationally best-selling writer, broadcaster, activist and trustee of the Homeless World Cup Foundation. She lives in Edinburgh, home to the Homeless World Cup HQ.

Introduction

This is not the story of the Homeless World Cup goal by goal or year to year but the story behind it – and the stories of the million homeless people who have been involved since 2003. It’s also the story as seen through my own eyes and shared with my friend Peter Barr, who has been part of the adventure from the start, as co-author of Home Game and also a fan of the Homeless World Cup.

The Homeless World Cup simply would not have happened without the conscientious efforts of the staff who made it possible. We have always had a tiny team in the international headquarters and they have worked all the hours under the sun to make the Homeless World Cup what it is today.

There are also hundreds of volunteers who support our national partners in more than 70 countries across the world, every day of the year. They are brilliant individuals determined to help homeless and excluded people change their lives through football. Some even fund-raise for the privilege of coming to the annual event where they usually work at least 16 hours every day.

The corporations, football authorities and the people behind the bids to host the annual tournament also deserve huge praise. Many of them have stuck their necks out to support the Homeless World Cup. They have played a really important part in our history.

And of course, this would never have happened without the courage and determination of the homeless people who have changed their lives completely, sometimes against all the odds. They are the real heroes – every single one of them.

There are so many people to thank, but it would be impossible to mention every single individual by name. You know who you are. So, please accept this as a personal thank you. This book is for you.

Mel Young

1

Hold Your Breath Time

Q: Will all the teams arrive on time?

A: It’s taken us ten years to get here…

FRIDAY, 5 OCTOBER 2012: I hold my breath. Just one more day. The tenth Homeless World Cup will kick off tomorrow in Mexico City, and everything’s ready for action – including three new stadiums for thousands of spectators which appeared overnight in the heart of the main city square.

The transformation of the plaza is almost complete. But this is not the first time that the Zocalo has seen dramatic change – it used to be the centre of the universe until it was destroyed by the Conquistadores. And now it is the venue for the Homeless World Cup.

The location may be different (last year it was Paris and the year before Rio) but every year I hold my breath right till the very last minute. Something unexpected always happens, but there’s nothing more I can do now except think about how far we’ve come since the tournament started in 2003, and how much more we’ll need to do to reach our goal – a world where homelessness has been eradicated altogether and the Homeless World Cup no longer needs to exist.

Every year is also very different. Every tournament takes on a life of its own and has a momentum of its own.

The scale of the event is also growing all the time, not just in terms of numbers but its international impact. Street-soccer teams from more than 50 countries are converging on the Zocalo – our home for the rest of the week. The 500 players selected to play for their countries will represent thousands of others who also played in tournaments during the year – about a million people since the organisation was founded just over a decade ago. And everyone who makes it here tomorrow will be part of a sporting event that will not only transform the lives of the players but also change the way that homeless people are perceived.

Some players will be nervous as they sit looking down on the world tens of thousands of feet in the air, wondering what Mexico City will be like and hoping they will go back at the end of the week with the trophy. Most of them have never even flown before or owned a passport. Some have never even had identity papers. Most of them have never spent the night in a hotel before, and some of them have never even slept in a bed with a mattress, a pillow and sheets. But all of them are gearing up to represent their country and heading for the most important week of their lives. In 24 hours, these homeless men and women – once excluded and invisible – will be treated like heroes by thousands of fans crowding into the square.

Lisa Wrightsman will be flying here tonight from California with the rest of her team. Lisa is a coach now but she also knows exactly what it’s like to be a player, and was part of the first women’s USA team two years ago in Rio de Janeiro, when the games were played on Copacabana. She was one of the stars of the tournament then, and returned a year later as one of the coaches in Paris. Lisa also knows exactly what it’s like to be homeless, struggling to get free from drugs. Today she is running a programme for excluded women in Sacramento, using soccer to help them to transform their lives, just as she has also turned her own life around. She loves the game of soccer and has always dreamed of playing for her country. She is also in love with the Homeless World Cup and excited to see what will happen this year.

Coming in the opposite direction, 25-year-old Lukes Mjoka hopes that this week in Mexico City will be another stepping stone in his eventful life. Like Lisa, he made his début in Rio, playing for South Africa. And like Lisa, he’s also a coach now. His dream is to go back to Rio, where Pupo the manager of the Brazil team has offered him work as a coach. It’s a long way from the township in Cape Town when Lukes was a six-year-old boy being squeezed in through broken car windows to steal whatever he could get his six-year-old hands on. It’s also a long way from running his neighbourhood drug-dealing ‘business’. Now part of the coaching staff helping South Africa manager Cliffy (Clifford Martinus), Lukes will have to persuade him and Pupo that he is now ready to take on the challenge of moving across the Atlantic to Rio.

Arkady Tyurin used to be homeless, like Lukes. He is flying in from Russia, thinking this year will probably be his farewell to the Homeless World Cup. He has been involved since 2003 when the tournament started, so this is the tenth year he’s managed the team. Maybe it is time for someone else to take over. Was the highlight when Russia won the trophy in Cape Town in 2006? Perhaps. But the challenge continued. In Melbourne in 2008, the team reached the final again, this time losing 5-4 to Afghanistan. This year, it’s another group of players, with their individual battles and their individual hopes and desires.

‘Will I see you next year in Poland?’ I ask. And the look in his eyes says that Arkady is already starting to have second thoughts…

Melbourne was the first year Hary Milas got involved with the Homeless World Cup. Like most Australians, he loves sport and also loves the underdog, and as a referee he gets the opportunity not only to make sure the players respect all the rules of the game but also make new friends and meet up with dozens of old friends. He’s also confident that nobody will hate his decisions so much that they stab him – something which happened a few years ago in Australia, long before he started refereeing at the Homeless World Cup. For Hary, the annual event is about a lot more than just soccer. It’s all about people transforming their lives – not just the homeless players but Hary himself and all the other people who volunteer year after year.

Like Hary Milas, Alex Chan from Hong Kong is not one of the excluded, but his life has also been deeply affected by getting involved in the Homeless World Cup. Because Hong Kong is now part of China, there are no ‘homeless’ people in the eyes of the authorities, but Alex knows there are excluded people in the city, including many heroin addicts, and he has done something about it – his company sponsors the team. It’s a long way from Hong Kong to Mexico City, but Alex hopes that one day Hong Kong will also play host to the Homeless World Cup.

Harald Schmied knows a lot better than most what the Homeless World Cup is about. He’s not involved in day-to-day activities now and this year he is covering the tournament for Austrian TV, but Harald was one of the founders of the organisation and is proud of the progress made over the years since his home town Graz in Austria played host to the inaugural event in 2003. It’s grown from 18 teams to well over 60 teams this year, and partners in 70 countries. Every year is different but the ‘crazy idea’ still has the same impact on Harald and everyone else.

Also flying to Mexico City tonight are human rights campaigner Boby Duval from Haiti, Bongsu Hasibuan from Indonesia, Becca Mushrow (one of the youngest players in the tournament), Mauva Hunte-Bowlby (one of the oldest) and Aaron Ranieri (returning for the first time to the land where he was born) from England; Bill and Debbi Shaw from Michigan who are coming to support their adopted homeland, the Philippines; another ‘exile’ who has fallen in love with the people of Asia, Paraic Grogan, an Irishman now based in Australia, sitting near two of his star players, Chan ‘Ton’ Sophondara and midfielder Phiyou Sin from Cambodia; Ireland coach Mick Pender, who has been to every tournament since Graz in 2003, and hopes that his credit card will not be called into service this year; and us-based volunteer Chandrima Chatterjee, who confesses she’s fallen in love with the Homeless World Cup.

Boby is an activist who spent 17 months in prison in the mid-1970s as a ‘guest’ of Baby Doc Duvalier, the country’s much-hated dictator. Amnesty International and us President Jimmy Carter secured his release in 1977 and, 18 years later, Boby created Fondation L’Athletique D’Haiti, an organisation which provides soccer training, free school and free meals for thousands of children and ‘at-risk youths’, and is now a partner of the Homeless World Cup. In 2007, Boby was named CNN Hero of the Year for his work, but this year he is just pleased that his players have made it to Mexico City – Haiti has been battered by disasters in the previous couple of years and it wasn’t until the last minute that they managed to raise enough money to fly here. Two years ago, thousands of people made homeless by the devastating earthquake set up camp on the soccer field used by L’Athletique D’Haiti. Now Boby has a dream to build a brand-new stadium in Haiti which will rise like a phoenix from the rubble of Cité Soleil.

There are three million homeless people in Indonesia, and Bongsu was one of them for over 15 years until he started playing soccer with Rumah Cemara, the Homeless World Cup’s Indonesian partner, an organisation which helps people living with HIV/AIDS and people who are trying to stop taking drugs – intravenous drug use is the major cause of the killer disease in his country. Bongsu doesn’t know it yet but later this week the team will be wearing black armbands and he will dedicate his ‘goal of the tournament’, a superb overhead bicycle kick, in memory of a friend and former team mate who is about to lose his fight for life. Bongsu also doesn’t know that next year he will coach the team – and one more of his dreams will come true.

This is the first year that England have entered a women’s team at the Homeless World Cup and 52-year-old Mauva is the ‘rock’ at the heart of the team. She lost her home and spent two years ‘sofa surfing’ in London – one of the many ‘invisible homeless’ in so many countries. After ‘accidentally’ getting involved in the soccer, she loves it and hopes her five children and two grandchildren will be watching ‘live’ this week, via the website set up by the Homeless World Cup. Her team mate, Becca, also has her family rooting for her back home in England, and like Mauva and the other England players she’ll be keeping a diary to document what happens and set out her personal goals. One of the challenges for everyone is ‘learning about defeat’ but as the plane arrives in Mexico City, defeat is a long way from everyone’s minds – especially Aaron Ranieri’s, making an emotional return to the land of his birth for the first time since he took off from the very same airport at five years of age.

Bill and Debbi Shaw also have connections with two different countries, dividing their time between the Philippines and Michigan. The husband-and-wife team co-founded the Urban Opportunities for Change Foundation in Manila, which publishes the street paper Jeepney and has organised Team Philippines since Melbourne in 2008. The local managers now run the organisation but Bill and Debbi still support the team whenever they can. They first went to the Philippines in 2002 intending to stay for a year. Ten years later, they are heading for Mexico City to cheer on their adopted land and catch up with their Homeless World Cup family. Faith plays a big part in what motivates Bill, but he also believes that his idealism comes from his childhood and his parents’ views on civil liberty and resistance.

This is the fifth time Cambodia boss Paraic Grogan and coach Jimmy Campbell have come to the Homeless World Cup, and the first time for Chan ‘Ton’ Sophondara and the rest of the players. After a 30-hour flight from Phnom Penh via Paris, ‘the smallest player with the biggest heart’ is destined to capture the hearts of the fans, like every other player from Cambodia before him. Ton is also lucky because two of the squad haven’t made it to Mexico City – there were not enough funds to pay for their tickets but Paraic has promised them places in next year’s team heading for Poland. It is a bitter blow for everyone but midfielder Phiyou Sin, sitting near Ton, can’t contain his excitement. Like his hero, Portuguese superstar Christiano Ronaldo, he will play for his country tomorrow and hopefully help his team score a few goals.

Paraic is excited for the players around him, none of whom have flown before or been beyond the borders of Cambodia. He is also nervous – will Mexico City be safe, will his players get lost, will they cope with the crowds? Will the current team produce another coach like Ton’s brother Rithy, who played in Milan in 2009 and will cheer on the players from thousands of miles away, with fellow coach Sam Yi, who made his appearance in Melbourne the previous year? Paraic also puts his thoughts into perspective – Cambodia was not a safe place to go until only a few years ago, when he went there as a visitor the first time, for a taste of adventure. Surely nothing would faze these courageous young players who come from such a beautiful yet traumatised country, recovering from years of war and genocide? But if one of the players gets lost in the city, with no phone or passport…

For Chandrima, this is Homeless World Cup Number Three. Last year, she was forced to cancel Paris at the very last minute, because of a family emergency, but her experience in Rio de Janeiro and Milan was something she’ll never forget. With a degree in Biology and a Masters in Public Health, you may think that Chandrima would pursue a very different career, but she is beginning to live for the Homeless World Cup and hopes to get more involved in the future, working for Street Soccer USA.

Chandrima wants homeless people to have a sense of belonging. She also wants to help give the players their voice, so they can tell their story in their own words, and ‘help make their experience at the Homeless World Cup as great as it possibly can be’, so they go back at the end of the week with a feeling of accomplishment and lessons to pass on to others.

The excitement is building. One by one, the flights start arriving in Mexico City. Then something goes wrong.

Asamoah Martin and the Ghana team are stuck in the airport in Dacca. The airline staff have told him that he and his players need visas for Germany because they will be changing flights in Frankfurt, to catch their connection to Mexico City. The airline staff are wrong about needing the visas, but nobody knows yet. Martin is advised to stay right where he is, at the desk, but time is running out. The flight leaves in 25 minutes.

Not everyone who wants to be in Mexico City will make it for this year’s event. Some teams haven’t managed to raise enough money to pay for their tickets, despite everyone’s efforts. Some countries have decided to focus on next year or – like Zimbabwe – are faced with what seem insurmountable problems. They will have to follow the event from a distance, watching ‘live’ via the website, if they manage to find a computer and get themselves online. Our partner in Zimbabwe, Youth Achievement Sports for Development (YASD), took part in the Homeless World Cup in 2008, winning by a record score of 20 to nil over Belgium in one of their games, but this year they will not be able to join us. YASD coordinator Petros Chatiza and his colleague Filbert Neumann are still coping with the fallout from 2005, when three million people were made homeless overnight, when shanty towns were suddenly demolished by the government in Operation Clean Up.

At the same time as Petros and Filbert, David Duke will be watching the tournament online, in his Edinburgh office, wishing he could be there with coach Ally Dawson and the rest of the Scotland team. Once a player himself, appearing in the second Homeless World Cup in Gothenburg, Sweden, in 2004, David is now CEO of Street Soccer Scotland. The organisation has made a huge impact in Scotland and this year has attracted record sponsorship as well as the support of fellow Scot Sir Alex Ferguson, the manager of Manchester United, but David had to make a hard decision a few days ago. There wasn’t enough cash for him to fly out with the rest of the team, and because he had been to the tournament several times in the past, both as player and coach, it was time for some new blood. David also has other priorities, running the nationwide programme for hundreds of people – some of whom will play for Scotland next year.

As David composes an email to one of his sponsors, Biswajit Nandi (aged 16) and Surajit Bhattacharya (17) are kicking a ball around on a dusty patch of wasteland on the edge of Sonagachi, the largest red-light district in Kolkata and one of the largest in Asia. This is where Biswajit and Surajit grew up and also where their mothers are still busy working today, selling their bodies for a few hundred rupees. For both boys, the Homeless World Cup is a dream. They have heard all about it from friends who have played for Slum Soccer, the Indian organisation which has sent a team to the Homeless World Cup since 2007. This year, Team India has had financial problems, however, and will not be going to Mexico City. Maybe next year in Poland? Maybe Biswajit and Surajit will be stars of the team?

For Patrick Gasser of UEFA at a conference in Sarajevo, there is only a short time to go till he flies out to Mexico City, returning to the country where he studied Spanish 30 years ago. The meeting in the capital of Bosnia has focused on ‘football and social responsibility’, and the lessons UEFA has learned from supporting the Homeless World Cup has been one of the topics discussed. Now Patrick wants to go and see the power of soccer in action.

Sitting in her office in Amsterdam, Maria Bobenrieth wishes that she could be with us. Now Executive Director of Women Win (an organisation which promotes the cause of sport to empower young women), Maria used to be the Global Director of Community Investments at Nike, and is still a big fan of the Homeless World Cup. Nike has been a key sponsor since the first event in Graz in 2003, not just providing funds but also practical help, including volunteers and merchandise. For the Nike people who become part of the team for the week, it is more than just another major sporting event where the company’s logo is seen by the crowds – it has become an opportunity for something much more personal. And for Maria, it is one of her great passions in life.

Meanwhile, in Mexico City, Daniel Copto is busy preparing his Mexico players, including women’s captain Mayra Vazquez and her team-mate Ana Aguirre. Daniel also has a dream – to build a rehabilitation centre in Mexico City for the addicts who live on the streets of the city, sniffing solvents until they get high and have damaged their brains. Many current treatment centres use outdated and sometimes very cruel methods, and Daniel would like to create a safe place where the addicts are treated as real human beings, and take part in his soccer-based activities. The project has steadily grown through the years and today almost 30,000 people come along every week to play soccer, in various locations nationwide. Thirty-thousand seems like lots of people, but Daniel is also concerned about the future of the hundreds of thousands of ‘invisible’ people who officially do not exist, and the addicts and victims of violence who live on the streets. Tonight, however, he is focusing all his attention on Mayra and Ana and the rest of the players, because tomorrow they will represent their country in front of their passionate fans. Can the ‘home’ team triumph in the Homeless World Cup? The pressure is mounting.

Everyone behind the scenes in Mexico City is also getting ready for action. The local organisers have reserved most of the nearby hotel rooms for the hundreds of players, volunteers and officials arriving tonight. The media centre is already buzzing with dozens of journalists searching for stories. But they won’t need to wait very long. Every single player has a story to tell and the soccer will be full of human drama – and goals – from beginning to end.

The excitement is building but another player who will not be in Mexico City is 18-year-old Loredan Bulgariu. Loredan was one of the players selected for the Romania Homeless World Cup team, but on July the 17th, three months before the tournament kicked off, he was stabbed to death in Timisoara.

‘My heart broke when I heard the news,’ says Romania coach Mihai Rusos, when I meet him in Mexico City. ‘Loredan was one of our most talented players. He was very proud to wear the Number Ten shirt and was very excited about representing his country in Mexico City.’

Loredan’s death was yet another example of the dangers faced by homeless people all around the world. Sadly, it’s a fact of life that homeless people are often the victims of violence. While so many people are infatuated with celebrities and luxury lifestyles, there are millions of lives being ruined by poverty and homelessness, and also lives being lost.

As the action starts and everyone cheers on the players, the Romania team will be playing their hearts out for Loredan, keeping his spirit alive. And Mihai knows more Loredans are living in the streets who will play for Romania next year – and the year after that.

In between interviews – with Agence France Presse and the BBC – I sit down in my room to draft my speech for tomorrow. This will be the tenth Homeless World Cup, a milestone in our history, and this year’s tournament will be much more spectacular than ever before, so maybe I should say something special to mark the occasion?

I have an idea – to talk about ‘dreams’. The dream that we can put an end to homelessness. The dream that every player has of getting a job and a place to call ‘home’. Not just the dream of winning the Homeless World Cup but of winning the future. For some excluded people, any future at all is a dream.

I will work on it later. Every year, I talk about similar issues, but I know that whatever I say, it will be for the people who matter – the players. And for them, every word will be new.

Every year, journalists ask me what tournament I liked the most, and I honestly tell them that one event can’t be compared with another. Some are bigger and louder than others. Some are better organised and some are more spontaneous and full of surprises. But for the players, this will be their only tournament. They are only allowed to play one year, so others can follow them later. Some players may come back as coaches, but we never lose sight of the fact every tournament may be the only chance some people get to experience what it’s about.

Our local partners tell me they have found a translator called Andrea who will join me tomorrow at the opening ceremony to repeat my words in Spanish. We will need to rehearse. So I’d better get finished as soon as I can. Ten minutes should do it? Andrea wasn’t aware till this evening that she would be standing in front of the crowds in the stadium, speaking ‘live’ on national TV, but if she is nervous, I don’t really notice. And she probably won’t notice I’m nervous, too.

I never feel nervous because of the crowds or the cameras, but every time I speak, I am conscious it could make a difference to somebody’s life. You never know who may be paying attention and noting your words, whether it’s a billionaire or someone who doesn’t have one single cent to his name.

Later this week, I am giving a talk about the Homeless World Cup to a group of business people in Mexico City. What I say there will be different from my speech tomorrow morning, and the challenge is always to make it seem fresh, even though I’ve almost learned the words off by heart:

The story of the Homeless World Cup is a story of how homeless people have transformed their lives through the power of soccer. But first the bad news. According to the United Nations, there are 100 million homeless people in the world. Millions more are living in extreme poverty, unable to access even basic commodities like drinking water. Meanwhile, the global economic system means the rich are getting richer while the poor are getting poorer, and the gap between them widens every day.

Every word may be engraved on my mind but the message is just as important today as it was when the Homeless World Cup first began, almost ten years ago.

There is homelessness in every single country in the world. In the USA, the richest of them all, over three million people now live on the streets, including entire families. In every major us city, you see homeless people – and wherever you go, it’s the same sorry sight.

It’s hard for us to really comprehend such huge numbers – or know what to do. But I believe to make a difference we have to do something, no matter how small. If every single one of us did something constructive, together we could change the world.

Sometimes, small ideas grow much more than anyone ever imagines. The Homeless World Cup started as a very simple idea, dreamed up in Cape Town in 2001, over a couple of beers. Most people thought we were crazy and said it would never become a reality, but two years later, in July 2003, the first Homeless World Cup took place in Graz in Austria, with 18 nations taking part. And when the teams marched through the streets at the start of the week-long event, it was a very moving moment for me and the rest of the crowd, and the players proudly holding their national flags.

A lot of what we did in Graz is still the same today. We always try to play in the centre of cities, typically in the main square. Street soccer is a simple game to organise – you just need a ball – but we want to make it an exciting event for the crowd, so we erect small courts surrounded on all sides by stands, like a miniature stadium. And when the players enter at the opening parade, people cheer the same as at the Olympics.

Every year, three major changes take place in the people involved. First, the players stand there in their national colours, singing their national anthem with genuine pride. The way some of them have been treated, you could excuse them for ignoring or resenting the anthem, but most of them just sing their hearts out. They’re fantastic ambassadors for their countries, and they almost grow taller in front of your eyes. Homeless people usually have low self-esteem and confidence and tend to look downwards, but when they stand there, hands on heart, they’re suddenly transformed and look around the stadium – no longer stooped but standing straight and looking up, beaming with pride.

The second change is even more remarkable, in some ways – it’s the crowd who are watching and cheering them on. Normally, they tend to avoid homeless people, or even think they’re sick or dangerous. They won’t let their children go near them. Yet, during every tournament, the children queue for autographs and treat homeless players as stars.

So what happens? Why do people change their attitudes all of a sudden?

All we do is change the environment. The day before, the homeless man or woman is hanging around in the street. People walk past and ignore them. The next day, they are standing in a stadium, and everyone’s cheering. They are just the same people, both inside and outside. All we do is change the background and the way people see them, and a big change takes place. The stereotype is destroyed – and solutions begin to emerge.

The third change is the media. In Graz that first year, film crews and journalists turned up from countries all over the world – even from countries which were not taking part. On the day of the Final, there were hundreds of photographers and television cameras ringed around the pitch. There were thousands of stories in newspapers and on the web. And all the coverage was positive. Not 90 per cent or 99 per cent but 100 per cent positive.

Before then, most coverage of homeless people tended to be negative: ‘Homeless people are upsetting the tourists, so get them off the streets. Homeless people are thieves who are up to no good. Homeless people are a drain on the economy.’

But in Graz, it was totally different. And every year since…

After Graz, we did some research and discovered that 80 per cent of the players involved had changed their lives completely. They had found jobs and homes, gone into further education, become football coaches, and so on. The results were so impressive, I couldn’t believe it. I had worked with homeless people for several years and the statistics seemed too high to me – too good to be true. So, we checked and checked again and they kept coming back just the same. The idea was working. So we decided to hold the event every year.

In 2004, in Gothenburg, Sweden, 26 countries took part in the second event. In 2005, my home city, Edinburgh, hosted the tournament, after the event in New York had been cancelled at the very last minute due to visa complications, and 32 countries took part. It was a challenging experience for everyone involved, but we had great support from many local organisations, who provided everything we needed at very short notice, and the sun shone for seven days straight – which for Scotland is almost unheard of. In 2006, we went to Cape Town and 48 countries joined in, including many new African teams. We jumped up a level in Cape Town that year. The President of South Africa stood on the balcony – the exact same spot where Nelson Mandela had made his famous speech after his release from prison – and saluted the homeless players as they marched past at the opening parade. There were 100,000 people in the square that day. Later that week, Archbishop Desmond Tutu came to visit, on his birthday. He was scheduled to speak on the pitch for a couple of minutes but stayed for much longer, talking to the players and kicking a ball around just like a kid in the playground.

In 2007, Copenhagen hosted 48 countries, and something truly remarkable happened – my own country Scotland won the Homeless World Cup. In 2008, the event moved to Melbourne, where Zambia won the first Women’s Homeless World Cup. The men’s final was a classic between Russia and Afghanistan. The square was packed to overflowing. Afghanistan were leading with 30 seconds to go and Russia had a chance to equalise but missed an open goal and Afghanistan won – and the whole place went crazy. In his speech, the Afghanistan manager said there had been darkness in his country for the past 30 years and that this was the first time a light had come on – a moment I’ll always remember.

In 2009, we held the event in Milan and more big-name celebrities like Formula One World Champion Lewis Hamilton and Italian soccer legend Marco Materazzi came along to show their support to the players. In 2010, the Homeless World Cup moved to Rio de Janeiro, where the games were played on Copacabana and – surprise, surprise – Brazil won both the men’s and women’s tournaments.

In 2011, the event was held in Paris in the shadow of the Eiffel Tower on the banks of the Seine – another iconic location. Scotland won the trophy for the second time, beating Mexico in a dramatic finale, while Kenya won the women’s event.

Now, here we are in Mexico City – in the centre of one of the world’s greatest cities. We will see players changing in front of our eyes as thousands of people applaud them. We will see changes all around us.

But the Homeless World Cup is about a lot more than this wonderful annual event. The important work is done on the ground every week of the year when our national partners in more than 70 countries work with homeless people on the streets of their cities and get them involved, playing soccer. Some countries also organise their own national championships, to select the players they will send to the Homeless World Cup.

The annual event is a celebration of all the hard work which goes on all year round. It is our chance to tell the world about our real aims – to create change and to put an end to homelessness wherever it exists, through the power of sport.

Homeless players are only allowed to play once at the annual event – which is a stepping stone for them towards a new and better life. It’s not the end but the beginning of a life-changing process. Many players later return as volunteers and coaches. Others have become community leaders and now run their national programmes.

All of them prove that we can create change. But we all know we need to do more.

Homelessness is bad for everyone. Ask anybody anywhere – rich or poor, old or young – if they think homelessness can ever be a good thing. I ask this question all the time and no-one has ever said yes. So, why do we allow it to continue?

Human beings are ingenious – we can send people to the moon, wipe out killer diseases, invent the Internet and speak to anyone around the world whenever we want – to exchange a few words or make billions of dollars. But if we are so clever, why do we have homelessness?

If we work together, we can put an end to homelessness now. And it’s simple – all you need is a ball. A ball can change the world and this week in Mexico City, we’ll prove it to you and the rest of the world…

So that’s the easy part. I know how I will end my speech on Thursday at the Embassy, but what will I say tomorrow at the opening? The tenth Homeless World Cup is a special occasion for me and the rest of the organisation but for every single player who stands there tomorrow, it’s the first time they have taken part in such an event. It’s probably the first time they have ever represented their country, and the first time for a long while that anyone has treated them with any respect. But no matter what I say, it’s the players who matter. It’s their dreams that count most. And the world needs to wake up and do something now to make homelessness something that only exists in the past.

Martin and the Ghana team are still stuck in the airport.

This is not the first time a team has been stuck at the very last minute with nowhere to go – or the first time that visas or identity papers have caused complications. In 2004, the Cameroon team were ready to fly out to Sweden. Every player had a passport but the immigration authorities were concerned they would ‘disappear’ during the tournament, and refused the team entry. The Cameroon project was recognised by numerous international organisations, and the Austrian authorities confirmed our exemplary record in Graz, but nothing we said seemed to work. Perhaps we were naive about official procedures, but the end result was that one of our teams didn’t make it. At the media conference before the Gothenburg tournament opened, the journalists were keen to hear the details of the ‘incident’, but I felt that it should not be the dominant theme – there were 26 other teams eager for kick-off and their arrival was a cause for celebration.

Cameroon, however, were not forgotten. Before we presented the trophy at the end of the Final, I asked the crowd and all of the players to send out a cheer that would ‘carry through the night sky and be heard by all the players left behind in Cameroon.’ It was an act of solidarity that echoes in my memory even today, and later on the players signed a shirt and other souvenirs of Gothenburg which they sent to the Cameroon players to tell them how much they were missed. Homeless people know what it is like to be excluded. They all have some experience of being outsiders.

There have also been many near-misses. In 2009, the Cambodia team almost missed the event in Milan with a few hours to go because they didn’t have the proper visas to pass through the airport in Bangkok, in neighbouring Thailand, despite the fact that no-one with a ticket to Europe was likely to try to abscond while in transit. Two years ago, I also held my breath, when it looked as if Uganda wouldn’t make it to Rio. Last year, Haiti were two days late getting to Paris because their airline wouldn’t let them board their flight, claiming that four of the women did not look like the photos on their passports. The airline eventually did let them on but when the team arrived, the tournament had already started. This was not the best way to prepare for competition, but the women stepped straight off the plane to make their début in the tournament – and win a load of respect.

World travel can be challenging for anyone these days, but for homeless people it can be impossible. Many of them have no identity papers and can’t even prove who they are – no birth certificate or even public record of their birth. As they try to survive day to day, the idea of applying for a passport never enters their mind. But if they want to play in the Homeless World Cup, in a faraway country, they need passports and visas, like everyone else.

Our national partners work hard with the players to get all the documents needed. This is often an extremely slow and complicated process. In some South American countries, for example, many homeless people were born on the street. They may have no idea when or where they were born – or even how old they are – and name themselves after the street where they live.

Once they get the basic papers needed, however, they are issued with identity papers, and this means they can also get a passport and a visa. Instead of being one of the ‘invisible people’ they can come to the Homeless World Cup and play in front of thousands of spectators in the stadium, and millions more who watch the games ‘live’ in countries all over the world.

There are millions of invisible people all over the world – non-persons or people who do not exist. A survey in London once asked people what they had seen in the street as they walked to their work in the morning. They mentioned cars, advertisements and window displays in the shops but not the homeless person sleeping in the doorway on a bed made from pieces of cardboard. They could not see the homeless people living in the streets, right in front of their faces. And that is just the surface of the problem.

Invisible people live their lives according to a different set of rules from the rest of society. They are forced to create an alternative reality in order to survive. A different set of values. No identity – never mind passports.

In Russia, for example, it is easy to find yourself outside the system. During Soviet times, the regime created a system which meant that everyone had to have an internal passport called a Propiska. It was illegal to go anywhere without it, and you had to get official permission whenever you wanted to move – that was how the Soviets controlled the population.

The problem is that if you didn’t have a Propiska, you were ‘outside the system’. You couldn’t own a house, you couldn’t work and you couldn’t get married or travel. So, you became a ‘non-person’ and you found an alternative way to survive. You existed but you were not part of society. You were excluded, and you soon became invisible.

When the Soviet system collapsed, the Propiska system was still in force. And overnight, many people also found themselves homeless. In the mid-1990s, I met an ex-soldier who had just become homeless. Like many Russian people, he was forced to do military service, and was sent to fight in Afghanistan. One year later, he went home to St Petersburg, and was told that his Propiska would be sent to him there.

He waited and waited, but his papers still did not arrive, so he made some enquiries and was told that the authorities had no idea where his papers were. And to complicate matters, he could not get a new Propiska because he did not have any identity papers to prove who he was. So, how could he get new identity papers? ‘You need a Propiska!’ the authorities told him.

So this young man who had been forced to risk his life for his country had ended up homeless and could not be a member of society because he had no way to prove who he was. Things are better now in Russia, but there are still too many homeless people – in Russia and everywhere else in the world.

Still no news from Ghana. Will they make it on time for the kick-off tomorrow? It’s just like the Uganda team two years ago, and nobody wants to go through all that heartache again, when no matter what we tried to do to fix the situation, as soon as one door opened, another door closed.

The Homeless World Cup gives homeless people a voice so that their stories can be heard and shared and valued just like any other human being. But in 2010, we had only a few hours to fix things or the Uganda team would miss their flight to Rio – and their voices would never be heard. That year, Uganda was one of 12 teams coming to play in the women’s event, and for me they were a special group of people. They had been living in a refugee camp set up during the Ugandan civil war, and what they had endured was unimaginable. They had been repeatedly raped, forced to marry soldiers whom they hated, and then have their children, while others had their own children forcibly taken away. Some had been forced to be sex slaves.