Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

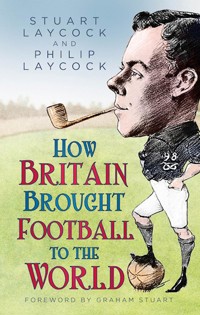

'Delighted to learn from this very enjoyable new book that the first ever game of football played in Austria was won by the Vienna Cricket Club.' - Tom Holland, Historian and Broadcaster Have we matched Wembley 1966 and 2022, or lost again on penalties? As a football fan in the Home Nations, there is at least one thing of which you can be sure. Even if sometimes other countries play it better than us, they'll forever have to thank Britain for the fun, the excitement, the tragedy, the triumph, the pain, the pleasure and the sheer gloriousness of the best sport in the world. From Afghanistan to Zimbabwe, it was Britain that first spread the beautiful game across the world. Cornish miners took football skills along with their pasties to Mexico; Iraqi football legend Ammo Baba learnt the game at an RAF base; the Buenos Aires Cricket Club gave the world Argentine football; and Romanian dentist Iuliu Weiner got not one an English education but a passion for football too. This is a book about football, yes, but it is also a book about all the countries of the world, about shared passion and shared humanity. It's How Britain Brought Football to the World.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 438

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For Richard Laycock 1930–2021,a gentleman and a gentle man.

First published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Stuart Laycock and Philip Laycock, 2022

The right of Stuart Laycock and Philip Laycock to be identified as the Authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 8039 9221 1

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Foreword

Maps of the World

Introduction

The Countries

Foreword

I knew world football came from here. I knew that much, but what I didn’t know was how that happened. I was lucky enough to play football at the top level in this country, I watch lots of football, and I have been involved in the game all my life but even I really knew only a little about how football spread across the world. It’s an amazing story, and something we can all be proud of.

Graham Stuart

Chelsea, Everton, Sheffield Utd, Charlton Athletic,Norwich City, England U-21

Maps of the World

North America. (Courtesy of d-maps.com/carte.php?num_car=5083)

South America. (Courtesy of d-maps.com/carte.php?num_car=2319)

Europe. (Courtesy of d-maps.com/carte.php?num_car=4577)

Africa. (Courtesy of d-maps.com/carte.php?num_car=4339)

Oceania. (Courtesy of d-maps.com/carte.php?num_car=284583)

Asia. (Courtesy of d-maps.com/carte.php?num_car=5161)

Introduction

There is nothing quite like the global phenomenon that is football today. There has never been anything like it in human history; so many humans, from so many countries and cultures, enthusiastically participating in and watching a single developed sport, with shared rules. And there may never, ever again be anything like it, because with football occupying such a dominant position in the world’s sporting passions, there is limited space for competitor sports to develop.

There are many reasons for the triumph of football, including its sheer playability in so many environments, with a ball, or anything that can serve as a ball, being about the only piece of essential specialist kit. We thought it would be fun to try to find out which countries got football directly from Brits and which got it indirectly. This book is about how a sport developed here in Britain, then spread across the globe to become the greatest sport in human history, bringing excitement and elation. Yes, there is occasional despair there too, but it is part of the positive genius of football that the despair is usually short-lived. There is always another match, another season, another tournament, giving the chance to replace defeat with victory.

When we set out to do the research for this book, we weren’t entirely sure where it would lead. We knew, like most people, that football came from here and spread across the world, and we knew some key Brits had been influential in taking football to key countries like France, Italy and Brazil. By the time we had finished the research, we had found the amazing story of how Britons were directly involved in the beginnings of football in about 60 per cent (well over 100 of them) of the world’s countries, and indirectly involved in the spread of football to the rest of the world’s countries. There are football monuments to many of these figures in the countries they helped, but few here, the country from which they came. That’s something that should and, we hope, will change.

To try to get as broad a picture of world football development as we could, the list of chapters is a hybrid. It contains all the UN member states (even those few who are not members of FIFA) but it also contains those entities that are not UN-recognised sovereign states, but are members of FIFA or a linked regional football association. The main chapters run in alphabetical order; however, to simplify the addition of some of the smaller of these entities, they have been added under a sovereign state chapter heading, where that might seem logical to the average British reader. So if you want to read something about football in Guadeloupe, look under France, if you want to read something about football in Guam, look under the USA.

Nobody is pretending that Britain’s role in spreading football across the world is without its controversies. One of the ways it was spread was through the British Empire and through colonial administrations. Racist attitudes were widespread among such colonial administrations, and so was exploitation of those being ruled by them. Sport had a role both in enforcing imperial rule and in resisting it.

However, the Empire was far from being the only way Brits exported football. British trade spread the game well beyond the political restraints of the Empire, and the pioneers who did so came from many walks of life, not just from the ranks of the Empire’s military and administrators. There were, for instance, sailors looking for entertainment on shore leave, miners and railway workers keeping fit, schools and missionaries aiming to build team spirit, and middle-class merchants extolling a British way of life. Many of the pioneers of football were Scottish.

Equally, nobody is pretending that the amazing world sport that is football today is solely the result of British talent and efforts. On the contrary, part of the genius of football is that in each country and culture, it has grown and flourished as a unique part of that country and culture.

Many different cultures have contributed to the way the game is played today. Brazil, Argentina, Italy, Spain, Hungary and Holland have, for instance, all helped develop our understanding of what makes good winning football. And even though it’s not the main purpose of this book, we thought it would be fun also to take a little look at how Britain and the countries of the world have helped each other out with the progress of football in the years since it started and where football in each country is at today.

The story of how football spread across the United Kingdom is also a fascinating one, but one already dealt with superbly in a number of excellent books, so we won’t be looking at that here. Current British Overseas Territories, like Gibraltar and Bermuda, come under the British umbrella, so you won’t find those in here either.

People were, of course, kicking round objects around in various parts of the world long before association football turned up, and we will mention some of those games as we work our way across the world. There are also, of course, other forms of football, with the Americans, Irish and Australians developing separate games, some of which have affected the development of soccer. We will be making some mention of those as well.

Women’s football deserves, and clearly has, a huge future. England’s spectacular victory in the 2022 Euros will do huge amounts for the game in this country. Women across the world often look to British women playing during the First World War as the start of their game. Due to the history of the game and of society around the world, and due to the situation today, more of this book is about the men’s game than the women’s game, but if we get to do a second edition we hope that will have changed.

All in all, it’s been great fun to write this book, and we hope it’s great fun to read. Read it in alphabetical order, or in any order you fancy!

A Big Thanks

In compiling this book we have looked at a huge range of sources, both in print form and online. This is not, though, an academic history, so we didn’t want to weigh it down with copious notes and a huge bibliography. We would, however, like here to pay tribute to and say thank you to some key sources and books we have found very useful.

We would like to make special mention, in no particular order, of Origin Stories: The Pioneers Who Took Football to the World by Chris Lee; The Ball is Round by David Goldblatt; African Soccerscapes by Peter Alegi; ¡Golazo! by Andreas Campomar; World Class by James Ferguson; A Journal of African Football History 1883–2000 by Barry Baker; Mister by Rory Smith; Feet of the Chameleon by Ian Hawkey; The Trouser People by Andrew Marshall; Fathers of Football by Keith Baker; Contested Fields by Alan McDougall; Football: The First Hundred Years by Adrian Harvey; Historia Minima del Futbol en América Latina by Pablo Alabarces; Fear and Loathing in World Football eds Gary Armstrong and Richard Guilianotti; Sport and Diplomacy ed. J. Simon Rofe; The Blizzard: The Football Quarterly ed. Jonathan Wilson; and the UEFA, FIFA and RSSSF websites. We would also like to thank Martin Weiler at Exeter City Football Club Museum Trust and The Grecian Archive, and Richard McBrearty and the Scottish Football Museum for their assistance.

The Countries

Afghanistan

It is not going to have escaped the notice of anybody here that the UK has fought in Afghanistan. A war in which we were involved there has just finished, and when football first really came to the country, a war there had also just finished.

The Third Anglo-Afghan War (yes, there were two even before that) started in 1919 and ended the same year in a bit of a draw really, but it did somewhat lessen British political and military influence over Afghanistan, and was regarded by many Afghans as a victory. The king who had led the war, Amanullah Khan, saw it as his mission to make Afghanistan more technologically sophisticated and more open to western cultural links. Part of that was football.

In the late nineteenth century, football was already well established a few miles to the south of Afghanistan, in Bannu, where English missionary Theodore Leighton Pennell had established himself in order to reach travellers to Afghanistan and where he had also established a local football team. In 1922, the Afghanistan Football Federation was founded, and in 1923 Amanullah Khan built the Ghazi Stadium in Kabul, which went on to become Afghanistan’s main football stadium. Amanullah Khan founded schools in which, among other subjects, English was taught, and soon school football teams were playing competitions.

The realities of geography and politics meant that, despite the Third Anglo-Afghan War, the cultural and sporting influence of Britain remained strong in Afghanistan. The British Legation in Kabul played a number of sports against Afghan competition in the 1920s and ’30s, including billiards, cricket and tennis, and also organised visits to Afghanistan from hockey and football teams from British India. In 1923, in the same year that the Ghazi Stadium was built, Amanullah Khan beat British civil servant Richard Roy Maconachie at billiards.

Amanullah Khan’s rule would end in a terrible civil war (by no means the last of those in the country in the last 100 years) partly brought about by his attempts to change Afghanistan. Football was not, however, eradicated. By the 1930s proper football clubs were being established, with Afghan teams now going on tour in neighbouring British India.

In 1948, Afghanistan joined FIFA and the Afghan national football team travelled to Britain to play in the Olympics. They were beaten 6-0 by Luxembourg, but they were there and they were playing international football.

The decades after were pretty thin on international football success for Afghanistan. And worse was to come on other fronts. First there was the Soviet occupation, then warlords fighting warlords, then the Taliban took over for the first time. Under the Taliban, the Ghazi stadium saw public executions take place. In one incident a woman was made to kneel near the penalty spot before being shot. A visiting Afghan team were also arrested by the Taliban for wearing shorts and had their heads shaved. However, the Afghan passion for football continued.

After the Taliban were removed from power by international forces and their Afghan allies, there was a definite resurgence of football, which Britain did something to encourage.

The British Army was involved. For instance, the Taliban fled Kabul in November 2001 and by February 2002, a mainly British team from ISAF (International Security Assistance Force) were taking on Kabul United, a team assembled from the best players of four local sides. Kabul’s national stadium was serving its intended purpose again. Kabul United scored first, but, in the end ISAF won 3-1.

And there was wider involvement from the British football community, too. British coaches, for instance, trained Afghan coaches.

An Afghanistan national women’s side was also created. In 2013 the national men’s side won the South Asian Football Federation Championship.

However, now the Taliban are in power in Afghanistan again. Many of Afghanistan’s women footballers have fled the country, and the future direction of football in Afghanistan, and indeed of the country itself, is uncertain.

Albania

Under communist dictator Enver Hoxha, Albania was a bit of a mystery to much of Europe, but it has had a fascinating history and, yes, football is a key part of that history.

Football first reached Albania in the early twentieth century, and it seems to have been first played there in the northern city of Shkodër. By that time, due to the large British presence in Malta, the game had already been long firmly established there, and it is reported that it was an Anglo-Maltese monk who, in 1908, brought the game to Albania. Locals watched students playing at the Roman Catholic Xaverian mission school and began to take an interest.

Somewhere in there also, though, are other influences. Some players in Shkodër, for instance, had experience of playing football in Italy, just across the Adriatic from Albania.

As so often, football here involved an expression of local and national identity. Albania had declared independence from the Ottoman Empire that year and, in 1913, Independenca Shkodër took on a side selected from part of the Austro-Hungarian armed forces that happened to be stationed in the area to help guarantee the new country’s borders. Despite the Albanians scoring, the Austro-Hungarians narrowly beat the team from the young nation, but still at least the young nation had a team.

And the Austro-Hungarian Empire shortly after suffered a much more serious defeat – in the First World War – and ceased to exist, while Albania, with its love of football continued. In 1919, KF Vllaznia Shkodër was founded and is still in existence today, one of the most successful clubs in Albanian football history.

The reign of King Zog, Italian occupation, the Second World War, and the creation of a communist state that would last until 1991 (or 1992 depending on how you look at it) were all to follow.

In 1946, Albania won the Balkan Nations’ Cup and the national team has had a few other successes over the years. For instance, in November 1965, at home in Tirana, Albania managed a 1-1 draw against Northern Ireland, when the visitors needed a win to qualify for the World Cup. More recently, Albania qualified for the 2016 Euros.

In 2011, the Albania women’s team played their first international, and Aurora Seranaj scored their first international goal, which was enough to give them victory in a friendly over FYR Macedonia.

Algeria

When you think of European connections to Algerian football, you tend to think of France. There is, of course, the football legend that is Zinedine Zidane, born in France to parents from Algeria. What a career! And what on earth happened in that World Cup final?

However, Britain too has strong links to Algerian football, and our involvement there started early.

Football was first played in Algeria in the 1890s by European expatriates, and prominent among those playing were, yes, the Brits. They even went as far as getting hold of The Football Annual 1896/7 from Britain to help improve their Algerian version of the sport.

In 1897, the first football clubs were formed in Algeria, and in 1906 the Royal Navy arrived to help give football a boost. A team from HMS Dreadnought took on Sport Club d’El Biar in front of a large, local crowd.

Football in Algeria started as a European game, but soon the local Arab population adopted it with a passion and started to express their own identity through it, forming their own clubs. In 1918, the Algiers Football Federation was founded, in 1919 the Constantine Football Federation too, and in 1920 the Oran Football Federation came along.

British involvement continued. For instance, in 1923 a team from the English North Nottinghamshire League toured Algeria and received gold watches from their hosts for their troubles.

Algeria has, of course, become a leading African football nation. The men’s national team have twice won the Africa Cup of Nations and have qualified for the World Cup four times. The women’s national team have qualified for the Women’s Africa Cup of Nations five times.

And people with Algerian heritage have, of course, made a big contribution to the sport in Britain. Look at Riyad Mahrez, for example.

Andorra

Andorra is a small principality in the Eastern Pyrenees and it has one of those nice national sides that rarely give British football fans a fright.

Andorra has a long history dating back to Charlemagne. Since the Middle Ages, its control has been shared between France and Spain. In 1993, it adopted a new constitution and joined the United Nations and the Council of Europe. These changes also led to the formation of the Andorran Football Federation in 1994 and Andorra joined FIFA in 1996.

While Andorra may be better known for its duty-free shopping and skiing, it has a reasonable football profile for somewhere with fewer than 80,000 inhabitants. The national team makes regular appearances in the qualifying rounds of World Cups and European Championships.

It’s probably fair to say that Britain played little direct role in the early development of football in Andorra, which has been dominated by the Spanish and Catalonia. This is hardly surprising given the geography of Andorra and Catalan is the national language. However, as we will see, Britain played an important part in the spread of football to Spain and Catalonia, so it did have some influence in the background. There is an Andorran club called ‘Rangers’, which may be a link to the British heritage of football, and the Andorran side played in the first qualifying round of the Champions League in 2007–08.

The first proper football club in Andorra, named simply FC Andorra, was founded in 1942. Britain was not involved as, apart from anything else, it was rather preoccupied with fighting Germany and Japan at the time. FC Andorra is now the principality’s major club, but it plays in the Spanish Second Division, rather than Andorra’s national league.

Andorra introduced a Liga Nacional de Fútbol in 1995. It has given clubs like UE Sant Julià, Principat, Santa Coloma, Rangers and Constel·lació Esportiva the chance to play on the European stage. For Andorra this is like the FA Cup. It gives amateurs and their supporters an opportunity to compete against professionals and experience larger stadiums.

A 1-0 home victory for Santa Coloma against Maccabi Tel-Aviv in the UEFA Cup in 2007 was the first victory for an Andorran side in Europe.

The national side has not found a lot of international success, and its first victory only came in 2004, a 1-0 triumph against Macedonia.

Andorra also fields a women’s team. In 1996, there were only a few female players in Andorra. There are now six teams playing in a league and there is a development programme to attract more girls and women to the game. So far, the women have beaten Gibraltar, in 2014, and Liechtenstein, in 2021.

Angola

Angola was a Portuguese colony when football arrived there, and it seems likely the sport arrived there via Portugal, rather than directly from Britain.

The first football in Angola seems to have been played around 1913–15, in, perhaps not surprisingly, its main port and capital, Luanda. Again, perhaps not surprisingly, considering the origins of football elsewhere in the world, both rail workers and military personnel seem to have been involved with the start of the sport in the country.

In the 1920s, close links between football in Angola and in Portugal led to the creation of clubs with strong attachments to some of Portugal’s football giants. Sporting Clube de Luanda, with links to Sporting Clube de Portugal, Sporting, was founded in 1920 and Sport Luanda e Benfica, with links to Sport Lisboa e Benfica, Benfica, was founded in 1922.

After a long guerrilla war, Angola became independent from Portugal in 1975, and the Angolan Football Federation was created in 1979. The Angola national men’s team qualified for the 2006 World Cup, and has qualified for the Africa Cup of Nations on a number of occasions, reaching the quarter-finals twice. The national women’s team came third in the 1995 African Women’s Championship.

Antigua and Barbuda

It’s probably safe to say that the popularity of cricket in this country has somewhat held back the development of football. The cricket legend that is Viv Richards, after all, comes from Antigua.

However, there is still plenty of passion for the world’s greatest sport in this Caribbean country – multi-talented Viv Richards has liked a bit of football. And, yes, football in Antigua and Barbuda does have a strong British football heritage.

The Antigua and Barbuda Football Association came into being in 1928 while the country was still a British colony, and some of the names of clubs in the country have a clear English flavour. There’s Point West Ham, Aston Villa, Villa Lions, Empire and English Harbour, for example.

The men’s national team came fourth in the Caribbean Cup in 1998, and in 2014 the women’s national team qualified for the Women’s Caribbean Cup.

And the traffic hasn’t at all been one way. For instance, Mikele Leigertwood was born here and has played for a number of English clubs, but he was also eligible to play for the Antigua and Barbuda national side, and did so.

Argentina

Yes, we gave Argentina football.

Of course, if the average England fan had to pick out any country, apart from Germany, as their bitterest football rivals, it would probably be Argentina.

Where do you start in describing that rivalry? Perhaps you start with the Falklands War of 1982, in the end a triumph for the UK and such a disaster for Argentina. But in football terms there was already something of a grudge. In 1966, England’s 1-0 victory over a ten-man Argentina in the quarter-finals ended in controversy and bad feeling. That football rivalry only became fiercer after 1982 and was brought to a head four years later. In the 1986 quarter-final in Mexico there was the goal Maradona infamously attributed to ‘the Hand of God’, followed famously by his ‘Goal of the Century’, as his team won 2-1.

There is, it has to be said, still something special in the air every time England and Argentina take the pitch against each other. However, with Argentine managers like Pochettino and Bielsa having served in the Premier League and with a host of talented players, including, of course, Sergio Agüero, Willy Caballero and Carlos Tevez, having played for major clubs, there is perhaps also a more positive view emerging of Argentina as one of the world’s great football nations.

The world’s greatest sport came early to Argentina. The Argentine Football Association claims that British sailors were kicking a cow’s bladder around with goals marked by stones in the 1840s. Certainly, Britain recognised Argentina as an independent country in 1825 and by 1831 there were enough British residents in Buenos Aires to establish Buenos Aires Cricket Club.

The first official football match in Argentina took place in June 1867. This is still very early, as the Football Association rules had only been agreed in December 1863 and Buenos Aires is some distance from London. A copy of the rules was passed through various hands to Yorkshireman Thomas Hogg, who was a member of Buenos Aires Cricket Club. The result was the formation of Buenos Aires Football Club, which played its first game between the Blancos (White Caps) and the Colorados (Red Caps). The result was a decisive 4-0 victory for the Blancos. The match was played to Association rules with some additions, and seems to have been a fairly rough affair.

Alexander Hutton, often considered the father of football in Argentina, was born in 1853 in the Gorbals, Glasgow, and eventually went to Edinburgh University to study philosophy. To fund his studies, Hutton got a teaching job at George Watson College. It took him nine years to get his degree, which, in some senses was perhaps fortunate as it meant he was still a student when Edinburgh University Association Football Club was set up in 1878. When he arrived in Buenos Aires in 1882 to teach, he brought with him not only a football and something with which to inflate it (handy) but also a deep enthusiasm for the game, which he passed on to the students at the school he established.

Alec Lamont, another Scot teaching at St Andrews School, organised the first Argentine football competition in 1891, calling it the Argentine Association Football League. It had a distinctly British or perhaps even Scottish flavour; teams included Old Caledonians and St Andrews Athletic Club. In its inaugural year St Andrews and Old Caledonians finished level on points. The championship was settled by a play off, which Old Caledonians won.

Hutton relaunched the AAFL in February 1893, becoming its president until 1896. It is this body that is usually seen as South America’s first national football association. Lomas, a club formed by Englishmen at Lomas Academy, won the first championship in 1893 and went on to win five of the first six titles before, inexplicably, switching to rugby. Another of those early clubs, Quilmes, started by the British as a rowing club, is now the oldest football club still competing in the championship.

Hutton left his mark on the league even after he ceased to be president. He formed the Club Atlético English High School for teachers and ex-pupils of his school. Known as the Alumni, they were to win the title ten times between 1900 and 1911. Thus the early years of the Argentine League were dominated by British teams and players.

The British can also lay claim to having started the spread of football beyond Buenos Aires. In Rosario, football began with the British-owned Central Argentine Railway Athletic Club, which Thomas Mutton formed in 1889. In 1903, Miguel Green led a move to change its name to Club Atlético Rosario Central and to allow locals who did not work for the railway to join. This created Rosario, one of the big teams of Argentine football.

Rosario’s great rival, Newell’s Old Boys, was also originally a British team. It is named after Isaac Newell. Newell was born in Kent, but in 1869, aged only 16, he accepted a job working for the Central Argentine Railway in Rosario. In 1890, he set up the Argentine Commercial School and later he founded Club Atlético Newell’s Old Boys for teachers and ex-students of his college. The red of their strip is supposed to represent England and the black Germany, as Isaac’s wife was German. By 1905, Newell’s was strong enough to take the Rosario regional league title from Rosario Central. Newell’s is now famous all over the world as the starting point for Lionel Messi’s football career.

At the start of the twentieth century, Argentinians began to form their own football clubs. The oldest is Club de Gimnasia y Esgrima La Plata. Originally formed in 1887, it added football to its unusual combination of gymnastics and fencing between 1900 and 1905. One of Argentina’s greatest teams, Club Atlético River Plate, emerged in 1901 from the merger of Santa Rosa and Las Rosales, and its great rival, Boca Juniors, was founded in 1905 by Genoese immigrants.

Visiting British sides also contributed to a growing enthusiasm for football in Argentina. Southampton FC was the first British club to tour in 1904 and they won all of their six games, scoring thirty-two goals. Nottingham Forest, Everton and Tottenham Hotspur all toured unbeaten before 1914. However, the speed with which Argentines were improving was evident when in 1914 Exeter City was defeated 1-0 by a select Buenos Aires XI.

By the 1920s, Argentine football was dominated by the locals, with a bit of help from their Spanish and Italian immigrants. The standard of the football was also improving, with a distinctive quick passing to feet style being developed on both sides of the River Plate in Argentina and Uruguay. Argentine supporters felt bitterly disappointed by their loss to Uruguay in the 1930 World Cup final. Their mood was not improved when Uruguay won the World Cup again in Brazil in 1950.

However, Argentine success on home soil in 1978 felt like an example of ‘football’s coming home’. It was a great display of Argentine talent and, on the back of it, Ossie Ardiles and Ricky Villa became early foreign imports for top British clubs. The 1986 Maradona-inspired World Cup triumph in Mexico confirmed Argentina’s place as a leading football nation.

Although British influence on Argentine football faded rapidly after the First World War and the formation of so many Argentine teams, Britain can still take some pride in certain elements of its national success as there have been a number of Brits or British families who have played for Argentina. Arnoldo Watson Hutton, the son of Alexander, scored one of the two goals in Argentina’s triumph over Uruguay in the Copa Lipton (a trophy given by the Glasgow tea magnate Thomas Lipton to be contested between Argentina and Uruguay). In total, Arnoldo won seventeen caps and scored six goals for Argentina.

Jorge Gibson Brown, known as ‘El Patriarcho’ (The Patriarch), featured in all ten of Alumni’s league titles between 1900 and 1911, and won twenty-three caps. There is also José Luis Brown, who scored for Argentina in their 3-2 victory over West Germany in the 1986 World Cup final. Even more recently, there is Carlos Javier Mac Allister, who earned three caps helping Argentina qualify for the 1994 World Cup.

Ultimately, the rivalry between England and Argentina is so intense, not just because of the obvious reasons, but also because for Argentines, as their captain, Roberto Perfumo, expressed it, ‘Winning against England is like schoolkids beating the teachers’.

Argentine women have also played against the Lionesses. In the 2019 Women’s World Cup, Phil Neville’s England defeated Argentina 1-0, but in 1971 at an unofficial women’s world cup organised in Mexico it was Argentina that emerged as 4-1 winners. Women’s football came early to Argentina, with the first match recorded in 1913 when two teams from Club Fémina in Rosario played each other. Ten years later, 6,000 spectators turned up at the Boca Juniors ground in Buenos Aires to watch Argentina defeat the Cosmopolitos 4-3. In fact, women’s football in Argentina in the 1920s became sufficiently popular that Andy Ducat, an English footballer, wrote to the sports magazine El Grafico to complain about women playing a man’s game. Argentina never banned women’s football, but it didn’t do much to encourage it either; it just struggled along in the background for much of the twentieth century. However, in 2006 they won the Women’s Copa América and they earned their first World Cup points in 2019 by drawing with Japan. Maybe one day they will have the same star status as Messi and the men.

Armenia

Somewhat confusingly, the first Armenian teams may not have been in Armenia itself.

By the early twentieth century, Armenians were living widely across parts of the Middle East. In Turkey they played an important role alongside Britons, Greeks and locals in getting football started in places like Istanbul and Izmir. After expulsions and deportations and the deaths of huge numbers of Armenians during the First World War, however, the development of Armenian football in the 1920s mainly switched to Armenia itself, which from 1922 had been a part of the USSR. British footballing influence was swapped for Soviet footballing influence.

In 1935, a club named Spartak was founded in the Armenian capital, Yerevan. Like the rather better-known Spartak Moscow, this name is a typical Soviet-era one chosen in honour of Spartacus, the gladiator who led a slave rebellion against Rome. Yerevan’s Spartak would go on to be one of Armenia’s most successful clubs and to be renamed FC Ararat Yerevan. Yes, it’s Mount Ararat from the Bible; you can see it from Yerevan. There’s also now an FC Noah.

Armenia became independent again in 1991. Scot Ian Porterfield was coach of the Armenian national team in 2006 but sadly he died in 2007. Not long ago, Armenia was promoted to UEFA Nations League B. The women’s national team has not had a lot of international success so far.

Henrikh Mkhitaryan is perhaps the best-known Armenian footballer of the modern era and, in May 2017, he scored in the Europa League final as part of the victorious Manchester United team.

Australia

Well, among other sports, we gave them cricket and we gave them football. It is, of course, a very long time since Australians were in any sense junior to us on the cricket pitch, but at least we are still bigger in football.

Football in Australia predates the Football Association in Britain. When European settlers first arrived, they found people playing some kind of ball game that involved kicking and catching. In 1859, Tom Wills, aided by his cousin Henry Harrison and journalists William Hammersley and James Thompson, drew up a set of rules for the game that was to become Aussie Rules football. Wills had been educated at Rugby School, where he captained the football team. His rules took influences from cricket, rugby, football and maybe even the old local ball game to create something fast-flowing and entertaining to suit Australian conditions.

Melbourne Rules Football, as Wills’s game was called, developed rapidly. Consequently, when association football arrived in 1880, Aussie Rules already had a firm grip on the nation. Rugby and cricket were also firmly established, so soccer had tough competition.

School teacher John Fletcher founded the first soccer club, Wanderers FC, in Sydney, in 1880. Their match against a King’s School team the same year has a strong claim to be the first proper association football game in the country. Fletcher then went on to start the New South Wales English Football Association in 1882 to administer the game. The name of the association made it clear that this game was English.

Australia became self-governing within the British Empire in 1901. By then football had spread a little. Balgownie Rangers FC, probably the oldest remaining football club in Australia, had been started by the Scottish miner Peter Hunter, and football associations had also been established in Victoria and Queensland.

Perhaps Australia’s most significant contribution to world football was the introduction of numbered shirts. These first appeared in 1911 when Sydney Leichhardt took on the wonderfully named HMS Powerful. It was not until 1928 that numbered shirts reached the professional league in England.

As Australians volunteered to fight in Europe in the First World War, they met British Army football teams. Balgownie captain James Masters led an Australian Imperial Force football team in France. After the war, football flourished in Australia. In 1921, the Australian Football Association was formed and Australia played its first official internationals during a tour of New Zealand. Unfortunately, Australia lost two of the matches but drew one. In 1925, an English touring party arrived and won all its twenty-five matches. Football still had some way to go in Australia.

‘Ladies’ teams had appeared in New South Wales before the First World War. The first official game was in 1921, when North Brisbane defeated South Brisbane at the Gabba in front of a large crowd. However, Australia was not yet ready to let women play. As in England, the AFA discouraged women’s football, arguing it was ‘medically inappropriate’.

Australia emerged from the Second World War with a football system still dominated by Brits and under-developed compared to Aussie Rules. Mass immigration from Italy, Yugoslavia and Greece changed this. The new immigrants were used to playing football, while cricket and rugby were too British for them and Aussie Rules too strange. Team names like Brighton and Bexhill were replaced by Polonia, South Melbourne Hellas, Side Sydney Croatia and Slavia.

Immigration helped raise standards of the national team in international competition. In 1974, the ‘Socceroos’ qualified for the World Cup, and in 1977 a professional league was started. Since 2006, Australia has qualified for every World Cup including 2022. Slav Aussies have contributed to the improvements.

Women’s football has also progressed, with a national league begun in the 1970s. Since 1995 the ‘Matildas’ have qualified for every FIFA Women’s World Cup. In the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, Australia defeated England in the quarter-finals.

Soccer still lags behind other Aussie sports but it has grown and home-grown soccer talents, including, for instance, Mark Bosnich, Mark Schwarzer and Mark Viduka (a lot of Marks), have played their part in English football.

Austria

In some countries, football offers a sense of continuity that national politics can struggle to match.

There have been a lot of big changes in Austria in the years since the game was first played there at the close of the nineteenth century. Then, it was part of a large multicultural empire, stretching as far south as Montenegro and as far east as Ukraine and Moldova, which contained 52 million people. At its centre was Vienna, famed for its café culture, science, music and art. A city ready to adopt new ideas, including football.

While there was some football played in schools from 1876, which may have had a British connection, it was in 1894 that football really started. The first recorded game was in Graz between two teams organised by the Academic Technical Cycle Association in the spring of 1894, but it was in Vienna that the first two clubs were founded, within days of each other.

First Vienna FC was, as it happens, the first to register. Convenient that. The club developed from a little kick-around in the grounds of Nathaniel von Rothschild’s large house. British gardeners took on the Austrians, with the Austrian Franz Joli, who had been educated in Britain, supplying the ball. The game was fun, the damage to Rothschild’s lawn less amusing.

Their rivals, Vienna Cricket Club, were uniformly Brits, and although the club had actually been founded in 1892, two years later it also started playing football.

The first game between the two Viennese clubs was in November 1894, when the Cricket Club beat First 4-0. The local derby between the ‘Gardeners’ and the ‘Bankers’ was to become a feature of the Viennese social scene and in 1896 the British ambassador turned up to watch.

In 1897, John Gramlick (founder of the Cricketers) established a cup for the best teams in the Austro-Hungarian Empire and by 1911 a league had been established. Austria joined FIFA in 1905 and by 1907 Vienna had seventy football clubs, with about 300 in the Empire.

One feature of the expansion was tours by British teams and many of these were the work of Mark Nicholson. Nicholson had been a professional footballer in England and an FA Cup winner with West Bromwich Albion. In 1897 he became manager of Thomas Cook in Vienna, and he retained his enthusiasm for football alongside his passion for tours. He became the star of First Vienna and took on a mission to raise the standard of football in the city. He wrote articles about training and discouraged players from smoking and drinking in the days before a game. He also encouraged British teams to tour so that locals could see what top-class football looked like.

Oxford University toured in 1899. The following year Southampton FC, a professional side, were there. The Corinthians toured in 1904. However, the most influential visitors in 1904 were the Scottish clubs Rangers and Celtic. Rangers took home an Austrian goalkeeper, Karl Pekarna, but they left behind a concept of football as a skilful game with short passing, which was to shape the future of the Austrian game.

It was the combination of Austrian manager Hugo Meisl and the English coach Jimmy Hogan that was to refine the Scottish approach and produce the Austrian ‘Wunderteam’ of the 1930s. Jimmy Hogan played professional football for Burnley, Fulham and Bolton Wanderers, but it was as a coach that he really made his name. He was hired to prepare the Austrians for the 1912 Olympics in Stockholm. Hogan believed in possession football and saw ball control as the key skill and a craft that could be taught. Despite all his efforts, Austria was eliminated in the second round by the Netherlands.

Further development in Austria was halted by the First World War and Hogan was briefly interned before spending the conflict working with MTK Budapest in Hungary. It was not until he returned in the 1930s that the fruits of his labours became obvious.

Austria emerged from the First World War a very different country. Stripped of its empire, it was reduced to a population of only 6.5 million people. However, the world’s best sport flourished. The new government reduced the working day to eight hours and many Austrians turned to football in their new leisure time. There was money in the game too, and in 1924 Austria became the first country outside the UK to host a professional football league. The first Austrian football celebrity was Rapid Vienna’s Josef Urdil, nicknamed ‘The Tank’ (a comment on his stature rather than a military association). Made famous by exploits like scoring seven times in a game against Wiener AC, where Rapid had been 5-2 down at half time, he went on to endorse his own beer and have a song written about his exploits.

It was in the 1930s that Meisl, with some help from Hogan, was able to turn this domestic success into a national ‘Wunderteam’. In 1931, Austria became the first team from outside the United Kingdom and Ireland to beat Scotland. The following year, Austria was narrowly defeated by England in an entertaining game at Stamford Bridge. However, they did beat England in Vienna, in 1936, in one of England’s earliest defeats.

In the 1934 World Cup, Austria finished fourth after losing the semi-final to Italy, the eventual winners. In the 1936 Olympics, after a controversial quarter-final against Peru, Austria won the silver medal, again losing to Italy. Since the Second World War, Austria have qualified for the World Cup and the Euros on a number of occasions.

Women’s football started in Vienna in the 1920s with the founding of the wonderfully named First Viennese Ladies Football Club Diana. Sadly, the club was short-lived; as well as the usual hurdles, Austrian women also suffered the Anschluss and Nazi occupation, which brought an end to their playing.

Women’s football had been revived by the 1970s with unofficial international games and domestic competitions. A domestic league was begun in 1982 and in 1990 an official national team was formed. They have yet to qualify for a World Cup but did finish third in the 2017 Euros and went out against Germany in the 2022 Euros quarter-finals.

Among Austrians to contribute to British football have been Marko Arnautović and Christian Fuchs.

Azerbaijan

In recent years, Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan and a flourishing city on the western shores of the Caspian Sea, has become a major venue for international football. The 2019 Europa League final in Baku is a treasured part of Chelsea history, and a slightly less treasured part of Arsenal history. Many Welsh fans are also fond of Baku, after their side’s draw with Switzerland and defeat of Turkey there during the Euros in 2021.

Football has a long history in Azerbaijan, and yes, we played a key role in its beginnings there. Asked to think of an early area of oil drilling and exploitation, many people might suggest somewhere like Texas. However, natural gas flares from the earth have long been a part of the geology of the Caucasus and one of the most important areas for the nineteenth-century oil industry was the land around Baku. The oil and gas industry remains a key part of Azerbaijan’s economy today and the Flame Towers skyscrapers that you see in so many photos reflect the importance of fire in Azerbaijani culture.

Companies and workers from far afield flocked to Baku during the nineteenth and early twentieth century. Among the outsiders who turned up were Ludvig Nobel, elder brother of the man who created the Nobel Prizes, who would become one of the richest men in the world, and Joseph Stalin, who became famous (or at least infamous) for rather different reasons.

However, also among those who rushed to Baku were workers, who brought football and footballs with them. And a key element among those were the Brits. Teams were already being formed in the area in the first years of the twentieth century, and, in 1911, the first official championship was held in Baku. Winners? It was the British Club. And, to show it was no fluke, they won again in 1912!

Football has continued to be a passion in Azerbaijan since then. And there is one football connection that, in particular, forms a unique link between England and Azerbaijan. Yes, it’s that goal in the 1966 World Cup final. With England and Germany 2-2 and in extra time, Geoff Hurst smacked the ball against the crossbar and it then hit the ground. But where did it land? The man sometimes described as ‘the Russian linesman’ was, in fact, born in Baku. Azerbaijani Tofiq Bahramov reckoned England had scored. The rest is football legend. There is now even a football stadium named after Bahramov in Azerbaijan and a statue. Geoff Hurst himself was, appropriately enough, there for its dedication. Perhaps we should have a Bahramov stadium or statue here.

The men’s and women’s national team have used the Tofiq Bahramov Republican Stadium for some of their home matches, although, since 2015, Baku Olympic Stadium has been Azerbaijan’s leading football venue.

Bahamas

The islands are known for beautiful beaches, but rather less well known for football. However, there is a fascinating story of bravery behind the introduction of football to the country.

Soon after the start of the First World War, it became obvious to the British government that it was going to need all the manpower it could get in order to win the war. As well as making use of existing military forces from across the Empire, Britain looked to find new sources of recruits. There was already a regular West India Regiment, but in 1915, the British West Indies Regiment was also formed. In all, about 700 Bahamians would serve overseas in various units during the war. The soldiers served with bravery and distinction, both on the Western Front and in the Middle East. However, racist attitudes towards them were common among the British authorities, and in late 1918, after the war’s end, resentment at unfair labour, pay and promotion led to some BWIR soldiers in Italy refusing to obey orders, and attacking officers. A lot of the veterans returned home determined to fight for equality and self-determination in their Caribbean homelands.

Some of the Bahamian veterans also returned home with a love of football and, presumably, with some footballs. By the 1920s, there were regular matches being played on New Providence, the main island in the Bahamas. As elsewhere, Royal Navy sides, from ships in the area, would sometimes drop in for games.

Leagues were organised in the 1950s and the Bahamas Football Association was eventually founded in 1967. Their record of international success has been somewhat modest so far, but the men’s team did recently earn promotion from League C to League B in the CONCACAF (Confederation of North, Central America and Caribbean Association Football) Nations League. The Bahamas are very close to the USA and Bahamians have had rather more success in some other sports, like basketball.

Bahrain

Football first came to Bahrain when British influence over the country was strong. From 1926 to 1957, Sir Charles Dalrymple Belgrave was chief administrator to the rulers of Bahrain and had extensive power over developments in the country.

One of those developments was football. Already, by 1928, sports clubs were being founded, like the one that would become Al-Muharraq SC, one of Bahrain’s biggest and most successful clubs. By 1931, there was a championship being competed for by RAF and company teams.

Bahrain was on the Allied side in the Second World War and actually got bombed on one occasion by long-range Italian bombers aiming at its strategically important oil industry. But not even Italian bombs could stop the advance of football in Bahrain (or indeed stop the oil industry).

The passion for the sport developed further in the country after the war. By 1957, there was a football association and by 1959, a national team. The team has received guidance from assorted British managers over the years and has had some successes. In 2019, for instance, Bahrain won both the West Asian Football Federation Championship and the Gulf Cup in the same year.

In 2014 the Bahrain women’s national team made football history when they played Italy and became the first Arab and Gulf women’s team to take on a European side.

Bangladesh

In 2021, Bangladesh celebrated a big birthday. It’s fifty years since a period of terrible violence ended with what had been East Pakistan becoming independent.

While Bangladesh is young, football in the area is quite old. The sport was introduced by the Brits in Dhaka, now the capital of Bangladesh, in the nineteenth century and the ‘beautiful game’ was to play an important role in the formation of the nation.

When football began, Bangladesh was part of the British Raj. Its proximity to Calcutta (now Kolkata) meant that locals were aware of the sporting prowess of Mohun Bagan (see India) and its Bengali links.

The British Army introduced the game to Dhaka at the end of the nineteenth century. There were matches between Army units and also between locals and British Army teams. Dhaka’s first team, the Wari Club, began in 1898. Between 1900 and the creation of Pakistan in 1947, football flourished. Club names show the influence of the Raj: there was the Victoria Club, founded in 1903, Dhaka Wanderers and East Pakistan Gymkhana Club. Other teams like Mohammedan Sporting Club were influenced by their namesakes in Calcutta. As early as 1915 Dhaka had a football league. Football skills improved rapidly. In 1910, Wari Club defeated a Royal Palace Team and in 1937 a Dhaka XI defeated the Islington Corinthians. Football success, in turn, encouraged local and national pride.

The partition of India in 1947 left India sandwiched between East and West Pakistan. East Pakistan had a real passion for football, with a wide variety of new clubs being formed. The old clubs, however, still dominated the league. Victoria Club won the First Division in 1948, 1960, 1962 and 1963, while Dhaka Wanderers were champions six times between 1948 and 1957. East Pakistan also had its own superstar, Abdul Ghafoor Majna, nicknamed ‘Pakistani Pelé’, who won trophies with both Mohammedan Sporting Club and Dhaka Wanderers.

When East Pakistan declared independence in March 1971, its provisional government was forced to flee to Calcutta. Players were recruited from the refugee camps in India to form a football team to be ambassadors for the new Bangladesh nation. ‘Shadhin Bangla Football Dol’ (Free Bengal Football Team) toured India to raise money and promote an independent Bangladesh. Before their opening game in July 1971 the team unfurled a green flag bearing a map of Bangladesh at its centre. The team played sixteen matches, winning twelve of them, but also raised large amounts of money and encouraged celebrities to side with the new nation.

While football is popular in Bangladesh and played a part in the formation of the nation, international success has been limited. In 2003 Bangladesh won the South Asian Football Championship and they were runners-up in 1999 and 2005. They have yet to qualify for a World Cup. The national team has had a number of English coaches.

Women’s football in Bangladesh has had a much shorter history than the men’s game there. A women’s tournament was organised in 2007 for eight regional teams, and there was a school competition the following year. Sabina Khatun has emerged as one of the stars of the women’s game in Bangladesh. She played for the national team at the South Asian Games in 2010, where she won a bronze medal, and has captained the side.

Barbados

This is another Caribbean country where football really got going in the early twentieth century when the country was part of the British Empire.