8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

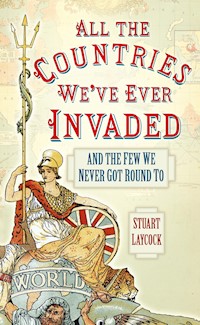

Out of 193 countries that are currently UN member states, we've invaded or fought conflicts in the territory of 171. That's not far off a massive, jaw-dropping 90 per cent. Not too many Britons know that we invaded Iran in the Second World War with the Soviets. You can be fairly sure a lot more Iranians do. Or what about the time we arrived with elephants to invade Ethiopia? Every summer, hordes of British tourists now occupy Corfu and the other Ionian islands. Find out how we first invaded them armed with cannon instead of camera and set up the United States of the Ionian Islands. Think the Philippines have always been outside our zone of influence? Think again. Read the surprising story of our eighteenth-century occupation of Manila and how we demanded a ransom of millions of dollars for the city. This book takes a look at some of the truly awe-inspiring ways our country has been a force, for good and for bad, right across the world. A lot of people are vaguely aware that a quarter of the globe was once pink, but that's not even half the story. We're a stroppy, dynamic, irrepressible nation and this is how we changed the world, often when it didn't ask to be changed!

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

First published 2012

This paperback edition 2013

Reprinted, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2020, 2021

The History Press

97 St George’s Place,

Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Stuart Laycock, 2012, 2013

The right of Stuart Laycock to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7524 8335 1

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound by Imak, Turkey

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Introduction

1 Afghanistan to Burundi

2 Cambodia to Dominican Republic

3 East Timor to France

4 Gabon to Hungary

5 Iceland to Jordan

6 Kazakhstan to Luxembourg

7 Madagascar to Norway

8 Oman to Portugal

9 Qatar to Rwanda

10 Saint Kitts & Nevis to Tuvalu

11 Uganda to Vietnam

12 Yemen to Zimbabwe

Conclusion

Maps

If someone asked you how many countries we’ve invaded over the centuries, what would you say? Forty? Fifty? Sixty? What if I told you that we’ve invaded, had some control over or fought conflicts in the territory of something like 171 out of 193 UN member states in the world today (and maybe more)? Because that’s exactly what we’ve done. It may come as a shock, but it’s true. Writing this book has changed the way I think about who we are as a nation, and in that sense about who I am. Maybe it will change the way you think about yourself too.

This book sprang from my son Fred asking me about countries that we have invaded. Once I started compiling in my mind a list of them for him, I found the list growing longer and longer. In fact, it turns out that there are relatively few countries on the planet that we haven’t invaded at least once, and there are quite a few countries that our forces have visited on more than one occasion, sometimes a lot more than one occasion.

A lot of people are vaguely aware that a quarter of the globe was once coloured pink to represent British-held territories, but that’s not even half the story. Sometimes, because we’re used to it, we forget quite how unique our story is. When you read how many times we’ve invaded, for instance, China or Egypt or Russia, ask yourself how many times Chinese or Egyptian or Russian forces have invaded Britain. We’re a stroppy, dynamic, irrepressible nation, and this is a story of how we have changed the world, even, often, when it didn’t ask to be changed.

I’ve tried to be objective, but sometimes the question of what constitutes an invasion can be a little subjective.

The book is, in some sense, focused on British forces actually setting foot in foreign countries, but it would be unfair to ignore the question of times we have invaded the maritime territory or airspace of other countries. Since we were long a massive naval power and have used sea power as a deliberate method of enforcing British influence, it would be wrong to exclude naval actions in other countries’ waters. Air raids in recent years have played a similar role. However, air raids, being individually of comparatively short duration, somehow seem less of an invasion (even though those underneath them may disagree), than naval or land action, so I have not concentrated on these.

There are many instances where we have negotiated and sometimes paid for our initial toehold in a land, and then gradually gone on to develop and expand our control of the territory. Even though there may have been no actual violence in the initial arrival of armed Brits, it seems reasonable to include such instances.

Similarly, there have been instances where our military incursions into a territory have been in support of the locals, rather than against them, but as with the D-Day invasion of France, it would be wrong to exclude these too.

I’ve not generally included military actions by British soldiers in foreign armies (of which there have been over the centuries far, far more than the average Briton is now aware), unless they seem of particular interest, or unless they were in some way fighting with British government encouragement. When it comes to questions of, for instance, pirates, privateers and armed explorers, the question becomes a little more complex, but it seems fair to include some of the more interesting efforts by privateers operating with official approval.

In this book, I’m basically looking at invasions of other countries by the current United Kingdom of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, and predecessor political entities, or by bodies that in some significant sense represent them. So, there is a section on invasions of the current territory of the Republic of Ireland in here, but not on invasions of the current territory of Scotland and Wales. Similarly, I haven’t covered our existing other territories such as the Falklands, Gibraltar, and so on.

In the same way that your family history, with both the good bits and the bad bits, is part of who you are, so, too, is your country’s history also part of who you are. This book is probably primarily going to be sold in the United Kingdom to Britons, so I don’t apologise for using the word ‘we’ when I refer to something past Brits have done.

As well as British, I’m also English, and therefore you will find me using the word ‘we’ about something done just by England and the English, not by Brits as a whole. I have tried to minimise this, because this book is supposed to be mainly about Britain’s record of invading the world, rather than just England’s, but I know I have done it sometimes.

I also hope anyone in Northern Ireland who is a citizen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, but does not regard themselves as a Brit, will forgive me for sometimes using the terms Brits, Britons and Britain as shorthand for the whole UK and its citizens.

Similarly, I am well aware of the contribution made throughout Britain’s history by immigrants, some of whom may not have been under the laws then, officially British. And I am also aware of the huge contribution to British military efforts made over the centuries by people from other parts of the empire and Commonwealth, as well as Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Again, I hope that my use of the terms Brits, Britons and Britain as shorthand, often to include the hugely significant contributions from these sources, does not in any way detract from their importance.

We are a nation with a long and spectacular history, so it is clearly impractical to give detailed accounts of every invasion we have ever carried out. For that reason, I have concentrated on the more interesting and more unusual ones, with a tendency to concentrate on the less well-known ones. D-Day, for instance, is hugely interesting but it is well known and covered in great detail in a large number of books, so there seems little point in focusing on it too much in this modest little book. Equally, the stories of our involvement with what were some of the major elements of the British Empire, like India or Australia, are fascinating ones, but have received comparatively extensive coverage in British books and media over the years, so I have not focused too extensively on them in this book. Even then, with interesting, unusual and less well-known invasions it is still not possible in a small book like this to give anything more than brief details. This isn’t so much supposed to be an account of our invasions, rather it’s intended to whet the readers’ appetites to go in search of more information elsewhere.

I have divided the book into sections based on today’s national boundaries, under the names of today’s countries. Clearly, many of these national boundaries did not apply at the time of many of the invasions in question, but it seemed the simplest and clearest way to approach the aim of this book. Modern country names and boundaries are what today’s readers understand best. Using them is the quickest and easiest way to grasp the enormity of our military influence and what a truly awe-inspiring power, for bad and for good, our country has been right across the world. And anyway, a change of country name rarely implies widespread change to a region’s people, its towns, cities or landscape. Moscow did not stop being Moscow when it went from being the capital of the Soviet Union, to being the capital of Russia.

Using modern boundaries also makes it easier to trace common themes in our activities over the centuries in particular areas. When we go into places like Iraq and Afghanistan, we are not going there for the first time. Even if a large section of our population is not aware of that fact, you can be fairly sure that a large percentage of the populations of the countries that we’re going into are well aware of our past appearances in their country, and while we do not have to agree with others’ views of us, it is always wise to be aware of them. We have been to almost all these places before, and we have made mistakes as well as had successes. Both past mistakes and past successes are worth considering when it comes to the present and future.

In terms of countries, I’ve included a section on every one of the world’s nations because there are only a few where people from Britain haven’t conducted some kind of armed operation, and even in those cases where they haven’t, there is usually something worth saying.

In terms of ‘what is a country’, the simplest method seemed to be to treat as a country those entities that the UK government recognises as separate independent sovereign states. So, I’ve looked at UN member states, plus the Vatican City and Kosovo, which even though they aren’t UN member states, are recognised by the UK government as independent states. There are some places around the world that some readers will feel should be countries or believe are countries, even though the UK government does not recognise them as independent sovereign states. Conversely, there are some places that some readers will feel should not be countries and believe are not countries, even though the UK does recognise them as independent sovereign states, but this little book is not the place to explore such questions.

Sometimes I’ve briefly written indications of where a country is located. This is not in any way a suggestion that these countries are in any sense less important than other countries. It is simply an acknowledgement that many Brits today, myself included, know less about the map of the world than they really should, and can also often be confused by countries that have similar names to other countries.

This book is most definitely not intended to be any kind of moral judgement on Britain’s history or the British Empire. From a British perspective it is still very easy to see our empire as a civilising force spreading democracy and moderation across the world, and there is, of course, some truth in that view. But as you read in these pages endless stories of raids and invasions, it is also easy to see another view, one that would perhaps be more easily accepted outside our borders.

In this view, the British Empire was almost like the last and by far the most successful of the Viking kingdoms, an empire which continued a North European tradition of using our knowledge and expertise at sea, gained from an inevitable close association with it, to leave behind a land of limited agricultural space with an often unattractive climate and sail away in search of loot, trade and power in warmer countries that seemed militarily vulnerable. The Saxons, Angles and Jutes had something of this in them after all. We had Viking kings of England like Cnut, and the word Norman is an abbreviation of Norseman.

It seems to me that some of the things we have done around the world are self-evidently wrong (like our deep involvement in the slave trade, which our later campaign against slavery in the nineteenth century only makes up for to a small extent), some are self-evidently right and there is a wide range in between. In some small way it’s a bit like your own life: there are things you’ve done that you’re ashamed of; there are things you’ve done that you’re proud of; there are things you’ve done that seemed like a good idea at the time, but don’t now; and there are things you’ve done that seemed like a good idea at the time and still seem like a good idea. Whether wrong or right, all are interesting because they are our history, the history of a nation that dragged itself out of a small, cold, wet island somewhere off the mainland of Europe to make a mark, for better or worse, on every corner of the globe.

This little book is a modest attempt to tackle what is an absolutely enormous and complex subject. It is inevitable that it will not be a completely perfect attempt. Our country’s history belongs to all of us, so if you feel I’ve missed out any essential details or got something badly wrong, do please let me know. And many thanks to those who have contacted me with corrections since the first edition was printed.

For world maps, please see pp. 253–6.

Afghanistan

We start with Afghanistan because in English it’s the country that comes first alphabetically, but it’s an appropriate place to start due to our long history of involvement in the country.

The Soviet war in Afghanistan in the 1980s was the first time that many Britons alive today became much aware of the country. A lot of our early involvement with Afghanistan has to do with the country’s strategic (and from the point of view of being invaded, let’s face it, unfortunate) location between areas of Russian control and influence to the north, and areas of British control to the south. This is the so-called ‘Great Game’, the battle for domination of Central Asia that was such a preoccupation with the Victorians. They called it a game, but it was the kind of game where people ended up dead in large numbers rather than just, for instance, being given a stern word by the referee or getting sent off.

Our first venture into the Great Game as far as Afghanistan is concerned could not, however, be described as a great success. Early signs of spreading Russian influence, plus a failure to conclude a British alliance with the emir of Afghanistan, Dost Muhammad, led to a British attempt at regime change. In 1838, a British army of 21,000 men set out from the Punjab to replace Dost Muhammad with a previous pro-British ruler of Afghanistan, Shah Shuja. The army successfully took Kandahar and advanced north. Eventually, Shah Shuja was installed as the new ruler in Kabul and over half the army left Afghanistan. Dost Muhammad was captured and sent to India. But the final whistle hadn’t blown. This wasn’t the end of this particular episode of the Great Game. It was only half time, and in the second half things went downhill spectacularly from a British point of view.

Shah Shuja was unfortunately fairly heavily reliant on British arms and British payments to tribal warlords to stay in power, and as it became apparent that the British were settling in for a long occupation, the Afghans weren’t too keen on the whole idea. A senior British officer and his aides ended up getting killed in a riot and when the local British agent, William Hay Macnaghten, tried to restore the situation by negotiating with Dost Muhammad’s son, Macnaghten was also killed and his body dragged through Kabul before being displayed in the Grand Bazaar. Not at all the sort of thing you want to see when you go shopping.

As the situation deteriorated almost as fast as the weather, the British commander in Kabul decided, in January 1842, that his situation was untenable and tried to negotiate safe passage out of the country for his force and the British civilians there. Instead of this, the retreating column was forced to try to make its way through snowbound gorges and passes in the face of heavy attacks. In the end, only a single Briton, a surgeon, Dr William Brydon, made it as far as the comparative safety of Jalalabad.

After this disaster there were plans to reoccupy Kabul, but a new government came to power in London determined to end the war and, instead, we made do with destroying Kabul’s Grand Bazaar as a reprisal, and withdrew back to India. Dost Muhammad was subsequently released and returned to power in Kabul.

After such a disastrous start, you would almost have thought that we might have left Afghanistan alone, but the Great Game continued so another round was almost inevitable. This time around, it all went a lot more smoothly for Britain. Well it would have been pretty unfortunate if we’d ended up with a disaster as bad as the first one on two occasions.

By 1878 Dost Muhammad’s son, Sher Ali Khan, was, after a spot of family feuding with his brother, now emir of Afghanistan. When a Russian diplomatic mission arrived in Kabul, Britain insisted that, as a balance, a British diplomatic mission should also be allowed there. The British mission was duly dispatched and was duly not allowed beyond the Khyber Pass. So we reckoned it was time we sent in the troops again.

This time an army of roughly 40,000 men, divided into three columns, invaded Afghanistan. Initial Afghan resistance soon crumbled, with the collapse aided by the death of Sher Ali Khan at Mazar e Sharif in 1879. After this, to prevent Britain occupying Afghanistan, Sher Ali’s son, Mohammad Yaqub Khan, signed the Treaty of Gandamak, handing over control of the country’s foreign affairs to Britain. Then, it will probably come as no surprise to you that the situation began to get complicated again.

In September 1879, mutinous Afghan troops killed the British representative in Kabul, Sir Pierre Cavagnari. And in the aftermath of this, General Sir Frederick Roberts led an army into central Afghanistan, defeated the Afghan army at Char Asiab and occupied Kabul yet again. That was then followed by yet another uprising against the British presence in Kabul, which was eventually put down, but by this time Britain had had enough of Yaqub Khan and decided that more regime change was needed. Splitting the country up was discussed, as were other options, before we finally made Yaqub’s cousin, Abdur Rahman Khan, emir instead. Then there was yet another insurgency, this time in Herat, which led to a British victory at the Battle of Maiwand, and finally, with Abdur Rahman Khan still in power and the Treaty of Gandamak still in force, the British Army managed to make a timely exit from Afghanistan. Glad to be out, no doubt.

Subsequently, Abdur Rahman Khan ruled Afghanistan with a heavy hand, but at least managed, on the whole, to prevent competition between Russia and Britain causing him too many problems. In 1919, though, his son and successor, Habibullah Khan, was assassinated and a power struggle ensued between his brother and his son, Amanullah. Eventually, Amanullah had his uncle arrested and decided that what was needed, in order to quell domestic trouble, was a nice little foreign war. So he invaded India.

At first sight this seems like a total mismatch, with Afghanistan up against the entire might of the British Empire, but in fact the situation was nothing like that simple. In 1919, Britain was exhausted after the First World War. What is more, just as today, cross-border loyalties there made it a difficult area for outsiders to operate in. However, unlike previous occasions, Britain now at least had an air force to assist it.

On 3 May 1919, the Afghan army crossed the border and captured Bagh. The Afghans hoped that an insurgency against Britain in Peshawar would help them, but we reacted quickly and managed to contain any possibility of rebellion. Eventually, on 11 May, British forces, including the use of planes, managed to push the Afghans out of Bagh and back across the border. Then Britain invaded Afghan territory again, and occupied the town of Dakka. But fighting was fierce and the situation was deteriorating behind the British advance. The Khyber Rifles became mutinous and began to desert. British Handley-Page bombers attacked Kabul, but the intended British advance to Jalalabad ground to a halt and things worsened when the South Waziristan Militia mutinied as well. Eventually, forces under Brigadier General Dyer pushed back Afghan army units and Amanullah offered an armistice which the British accepted. The war was in many ways inconclusive, but it did effectively mean we gave up on trying to control Afghan foreign policy. Instead it left us concentrating on the equally insoluble problem of trying to control the long-running and bitter insurgency in the North-West Frontier area that dragged on pretty much for as long as the Raj. As Great Games go, our venture into Afghanistan hadn’t proved to be such a great one from our point of view. Mind you the Russians haven’t exactly had a lot of fun in Afghanistan either. And, of course, it’s all brought a lot of misery to the Afghans. So not a Great Game from anybody’s point of view.

In the twenty-first century, of course, we returned to Afghanistan. After the 9/11 attacks in 2001, we joined the US-led Operation Enduring Freedom to topple the Taliban regime and remove Al-Qaeda from the country. After initial rapid military successes, attempts began to build a new Afghanistan, with a new, more liberal Afghan government. However, the Taliban never disappeared entirely, pushing international and allied Afghan forces into a long war against them. For instance, in 2009, President Obama temporarily massively increased US troop numbers in an attempt to destroy the Taliban permanently, and in 2010, a major NATO-led offensive, Operation Moshtarak, was launched in an attempt give the Afghan government firm and stable control of Helmand province. In 2014, after many bitter years of fighting and hundreds of British troops killed, an end to British combat operations was announced. However, the Taliban was still a significant force, and a small number of British troops remained for a variety of purposes including training local personnel. In 2021, as the Taliban seized control across the country, British forces finally withdrew from Afghanistan. It is hard right now to see the long, bitter war of the last twenty years as much of a success for Britain. However, it is too early to give a final judgement on what has and has not been achieved in that time. The Taliban are again in power, but they now rule a country that is very different to the one they ruled in 2001. How the Taliban will change that country in future years and how it will change the Taliban remains to be seen.

Albania

Ah, Albania, Land of the Eagles (see flag), but also, until not long ago, the land of the less than attractive dictator Enver Hoxha and place where you could spot a statue of Stalin as recently as 1980. This was a land so scared of invasion that it had large numbers of concrete pillboxes scattered across the countryside in a slightly bizarre and surprising fashion.

During the Cold War, most of Eastern Europe seemed remote and cut off to West Europeans. But Albania seemed remote and cut off even to most East Europeans. If you’d asked a selection of Brits in 1975 where Albania was, I suspect a fair percentage wouldn’t even have guessed it was in Europe. In fact, for anyone who grew up in the Cold War period, Albania was such a mysterious, closed land that it seems almost inconceivable that Britain’s armed forces could have a history of operations in the area, but, in fact, they do.

We tend to think of Trafalgar and Waterloo when we think of the Napoleonic Wars, which in some sense is fair enough, but we actually fought the French in all sorts of places, one of them being the Adriatic. The Albanian coast saw assorted actions by the Royal Navy during the Napoleonic Wars, including, for instance, the capture of the French corvette Var at the Albanian port of Valona (now Vlorë) in 1809 by HMS Belle Poule. You’ll come across some rather fabulous names for Royal Navy warships in this book. I know our modern Royal Navy doesn’t have that many ships to name, but when they do have new ones to name, it would be nice if they resurrected some of the more jolly ones from the past. The rather unusual name of this particular ship comes from the fact that she was a French ship until we captured her in 1806.

In the First World War, in December 1915, the Austro-Hungarian navy, aiming to impede the evacuation of Serbian troops retreating in front of the enemy onslaught (see Serbia), sent a naval force to attack Durazzo (Durres, Albania’s main port) which was then in Allied hands. British ships, including HMS Dartmouth and HMS Weymouth, stalwartly helped to repel the attack. And British troops landed in Albania to help the epic evacuation of the retreating Serbian army across a narrow stretch of sea to Corfu. Thinking of Corfu today, as the holiday island it is, you might be tempted to be jealous of people being evacuated to it, but this was before the days of sun-and-sand package tours. The retreat was long and bitter, and the evacuation was sort of Serbia’s Dunkirk. The brave men of the Royal Navy’s Danube Flotilla, who had made the long and grim retreat with the Serbian army, were also rescued.

Then in October 1918, with Durazzo now in Austro-Hungarian hands (so much for our efforts the first time round), Royal Navy ships, including HMS Weymouth, took part, along with, Italian, Australian and American warships, in the Second Battle of Durazzo. Shore batteries and assorted other buildings were destroyed, and a squadron of Austro-Hungarian patrol craft was defeated. Shortly afterwards, Austria-Hungary lost the war and HMS Weymouth could go off and do something else.

Early in the Second World War, we were back in the area. In 1940 and 1941, the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force (RAF) launched operations to try to help Greek troops by attacking Valona, treading in the footsteps or sailing in the wake of HMS Belle Poule almost 150 years earlier. For instance, on 19 December 1940, HMS Warspite and HMS Valiant (good names but much more obvious than Belle Poule) shelled Valona, destroying Italian planes. The Special Operations Executive (SOE), also got in on the act and conducted assorted operations here during the war, with the aim of assisting resistance.

In October 1944, sailing from Brindisi in Italy, Number Two Army Commando and 40 Commando, with help from a Royal Navy bombardment, fought their way into the southern Albanian port of Saranda, opposite Corfu, and took it from the German defenders.

Brits found themselves fighting alongside Albanian Communists during the Second World War, but such close ties were not to last. Shortly after the end of the war, relations between Britain and Albania were plunged into crisis over incidents involving the Royal Navy in the Corfu Channel.

Algeria

We don’t tend to think of Algeria as an area of British influence, so it may come as something of a surprise to find out that our forces have been in action here many times.

In the early centuries this mainly had to do with Algerian pirates. Britain, of course, has a long history of producing pre-eminent pirates and privateers, but we do tend to object when others play the game too well. The so-called Barbary Corsairs played it exceptionally well. They didn’t even just attack targets in the Mediterranean; they attacked ships and raided coastal areas as far north as Britain itself. All in all we didn’t like Barbary Corsairs. And some of the most successful North African pirates worked from the area around Algiers.

We tried to deal with the problem with a mixture of diplomacy and rather less subtle violence. By the 1630s we had partially effective treaties in force, but then things got messy and a treaty signed in 1671 broke down into open warfare. Defeats by British naval forces under Arthur Herbert forced Algiers to sign another treaty in 1682.

It’s worth pointing out at this stage, that even though we do have quite a record of attacking places around the world, it wasn’t just us having trouble with Algiers. Frankly, the city seems to have been a rather unsafe place to live at the time and you have to wonder what happened to the house prices. The French bombarded Algiers on a number of occasions, including in 1682, 1683 and 1688. So did the Spanish on a number of occasions, including in 1783 and 1784. In 1770, the Danish-Norwegian fleet had a go. Even the Americans, rather far from home, got in on the act by sending ships to Algiers in 1815.

We tend to think of military interventions on humanitarian grounds as a modern invention, but in 1816 we carried out what can, in some sense, be seen in these terms. It was our turn to bombard Algiers. With Napoleon finally defeated, we decided that it was time to do something (yet again) about the slave industry in North Africa. Admittedly, in this instance Britain was mainly concerned with preventing Europeans and Christians being enslaved, but it was perhaps better than nothing.

So Lord Exmouth set off for the North African coast to persuade the locals to stop their bad habits. And he took a small squadron of naval ships with him to make his arguments even more convincing. Indeed, the Deys of Tripoli and Tunis found Exmouth’s arguments, or at least the sight of the British Navy, thoroughly convincing and agreed to do as demanded by Exmouth. However, things proved a little more difficult in Algiers. Exmouth thought he’d succeeded only for events to end with a massacre of European fishermen we thought we were protecting.

Not surprisingly, people in Britain weren’t exactly happy about how it had all worked out, so Exmouth was sent back to drop a few less subtle hints on the Dey of Algiers, along with the threat of some even less subtle cannon fire.

For his mission, Exmouth took along assorted ships of the line, frigates and various other vessels. In Gibraltar, a Dutch squadron also joined the mission. Just as today, the safety of diplomats could be a problem in such situations, and the day before the attack a party from the frigate Prometheus tried to rescue the British consul and his wife, only to be captured. Not a huge success.

When the fleet was finally in position for the bombardment, an Algerian gun started the battle and a flotilla of small Algerian boats full of men tried to reach the British ships and board them. Neither Algerian guns nor the boarding parties achieved much and, instead, Exmouth fired at both ships in the harbour and the Dey’s military installations before withdrawing and demanding the Dey fulfil his demands about slaves and slavery. The Dey now finally complied.

In 1825, however, we ended up bombarding Algiers again. In some ways it’s surprising that people chose to remain living in Algiers, particularly since, in 1830, the French bombarded it yet again. Oh, and then invaded it as well. Which meant that the next time we returned to the area, it wasn’t the Barbary Consairs we were bombarding any more.

Mers-El-Kebir is situated in western Algeria, near Oran. In July 1940, a large number of French warships were concentrated here and Britain feared that because of the Vichy government’s relations with Nazi Germany, these ships could at some stage be used against us. So we shelled them.

In 1942 we were headed back to Algiers yet again, this time for Operation Torch. This operation involved landings in Vichy-controlled Morocco and Algeria, and a lot of the forces involved were American, but British forces also played major roles. The Eastern Task Force aimed at Algiers was commanded by British Lieutenant General Kenneth Anderson and included troops from the British 78th Infantry Division and two commando units, No. 1 and No. 6 Commando.

French Resistance forces staged a coup in Algiers, and when the Allied troops arrived they met little local resistance from Vichy forces. The heaviest fighting took place in the port of Algiers where HMS Malcolm and HMS Broke launched Operation Terminal to try to prevent Vichy forces destroying the port facilities. Both ships came under heavy artillery fire in the port and were badly damaged, but HMS Broke managed to land the American troops it was carrying, before withdrawing. HMS Broke was, it turned out tragically, indeed broken, and eventually sank from the damage it received in the operation. The American troops who had landed were eventually forced to surrender, but, at least, the port was not totally destroyed.

Andorra

A small country that regularly gets loads of British visitors, particularly skiers, these days (I’ve been there myself), but so far I can’t find any evidence we’ve ever invaded with troops. During the Second World War, some British airmen did use Andorra as a route to escape from occupied France, but that’s maybe the closest we’ve come to sending British troops into Andorra. If anyone knows differently, let me know. Small countries make for small targets and have a disproportionately high representation in the short list of places we’ve never really invaded.

Angola

A land that has seen a lot of devastation from war in its history, but very little of it has been down to us. During the colonial era this was an area largely of Portuguese influence and since we have a long-standing friendship with Portugal, we’ve thoughtfully tended to steer clear of invading places like Angola.

Early on we did take a bit of interest in Cabinda, a slightly detached part of Angola, but a part of Angola nonetheless. Cabinda has a strategic location at the mouth of the Congo, so it was inevitable that we would be interested in it. Britain’s Royal African Company built a fort there, only to have it destroyed by the Portuguese who weren’t too keen on us getting a share of the region’s trade, even if we were supposed to be friends.

Then when we finally stopped being a slave-trading nation and started actively fighting the slave trade, the seas around Angola saw plenty of Royal Navy activity. The 4th Division of the Royal Navy’s West Africa station covered from Cape Lopez in Gabon to Luanda in Angola. And the 5th Division covered the area south of Luanda.

In the largest British deployment to Southern Africa on active service since the 1960s, 650 British troops on UN duty set foot in Angola in 1995 as part of Operation Chantress to help protect a ceasefire. A friendly invasion.

Antigua and Barbuda

From the point of view of Brits invading it, Antigua has a nice straightforward history. English settlers turned up on Antigua in 1632 and first England then Britain controlled it all the way through until 1981.

Except for 1666 – a bad year for us in many ways. Not only did we have the Great Fire of London and the Great Plague (great in the size sense rather than the ‘Ooh, fire and plague, Great!’ sense), but as if all that wasn’t bad enough, the French turned up and briefly occupied Antigua. When you look at a list of governors of Antigua, your eye runs down the British names until you get to one ‘Robert le Fichot des Friches, sieur de Clodoré’. I don’t know if there ever has been an English branch of Robert’s (pronounced Robaire) family, but he at least was most definitely French.

We had a little more trouble with Barbuda. Our first invasion wasn’t a huge success, well at least not for the Brits involved. It was a bit more of a success for the locals already living on the island.

By 1685, however, Christopher and John Codrington, who were involved with sugar estates on Antigua, were granted a lease on Barbuda by Charles II. Barbuda was the scene of a number of uprisings by slaves in the eighteenth century.

Argentina

Yes, they invaded the Falklands. Yes, we’d already invaded Argentina a long time before that. Equally unsuccessfully, though.

We’re all aware of the failed Argentinian invasion of the Falklands in 1982. One thing most Brits are a lot less aware of is the failed British invasions of Buenos Aires in 1806 and 1807.

Argentinian waters saw a fair number of armed British ships between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, but it was in the nineteenth century that we took a really serious interest in the area.

We had long harboured ambitions in South America and since we were yet again fighting Spain, which then controlled the territory of present-day Argentina, Major General William Beresford, prompted by Admiral Sir Home Riggs Popham, decided that even though there were no official orders from the British government to do so, it would be a good idea to invade Buenos Aires. It wasn’t a good idea. It was a terrible idea, in fact.

There had been a sort of concept in Britain that the locals might welcome getting rid of the Spanish, but it didn’t entirely work out like that. We took Buenos Aires easily enough in June 1806, and some locals were pleased to see us, but quite a lot were not. One Santiago de Liniers helped organise a fight-back against us and raised militia forces, eventually leading to bitter fighting and Beresford’s surrender in August. It was all highly embarrassing and more than a little humiliating. Our occupation of Buenos Aires had lasted forty-six days, even less than the Argentinian occupation of the Falklands.

In 1807 we were back, but things went even worse this time round. In July, Lieutenant-General John Whitelocke led our second attempt to take Buenos Aires. From the start our forces met stiff local resistance and, once again, a British commander was forced to sign another humiliating deal over Buenos Aires. When he got back to Britain, Whitelocke was court-martialed and dismissed from the service.

You’d think somehow after two such major disasters we might have left the area alone, but we were back in Argentinian waters later in the nineteenth century. We occupied an Argentinian island, Martín García, for a time and conducted the British and French Blockade of the Rio de la Plata, the British part in this lasting from 1845 to 1849. We don’t seem to have achieved anything very much with that effort either.

Armenia

British troops were active in parts of current day Armenia in the chaotic era after the Russian Revolution and around the end of the First World War, and after that. We operated in the area of what is now the border between Turkey and Armenia, with a garrison at Kars just inside Turkey, but also with units active in Armenia in the area around what was then Alexandropol, now Gyumri. For instance, 27th Division’s Southern Command area included Armenia’s capital, Yerevan. We dived in with high hopes and then failed to solve loads of the major political and ethnic conflicts affecting the area at the time. The troops were eventually pulled out from the Caucasus when it was felt that the cost of maintaining them there was no longer justified by what they were achieving, and lots of people at home were sick of the venture anyway.

Australia

In the seventeenth century, the Dutch were the first Europeans to reach Australia and map it. A Brit named William Dampier landed here briefly in 1688 and again in 1699. Then along came Cook in 1770 and claimed a big chunk of the land for Britain. He was followed, in 1788, by Captain Arthur Phillip with the First Fleet and its contingent of convicts into Port Jackson to set up a settlement at Sydney Cove on 26 January. The colony of New South Wales was declared on 7 February. Another fleet of convicts arrived in 1790 and a third in 1791. By 1793, free, non-convict settlers were also arriving. Slowly we began to take control of the whole of Australia.

In 1803 a settlement was attempted on Tasmania, and in 1804 Hobart was founded.

The Swan River Colony, which was to become Western Australia, was declared in 1829. And in 1836 South Australia was declared. Victoria was established in 1851 and Queensland in 1859. The Northern Territory came into being in 1911.

There was some local resistance. For example, a man called Pemulwuy organised resistance to the settlers between about 1790 and 1802. In 1797 he led about 100 men against British troops at the Battle of Parramatta. He was killed in 1802. In 1824, with conflict breaking out between settlers who had crossed the Blue Mountains and the local Wiradjuri warriors, martial law was declared for a period of some months.

Between 1828 and 1830 there was resistance to the British on Tasmania.

In the 1830s, Yagan, a warrior of the Noongar people, was to engage in clashes with settlers in the area around Perth. After he was killed, his head was cut off and brought back to Britain. It was only returned to Australia in 1997.

Examples of resistance continued. The Kalkadoon people kept settlers out of Western Queensland for up to a decade until their defeat at Battle Mountain in 1884.

Australia became independent from Britain through a series of steps that gradually gave it more and more control over its affairs.

Austria

It’s strange isn’t it? Somehow, today we tend to think of Austria as almost not a military country, in the sense that we don’t now particularly associate it with fighting wars (though according to the Afghanistan ISAF website at the time of writing it has three troops in ISAF). A bit like Switzerland, perhaps it’s all those mountains and snow, and lederhosen (though, apparently, lederhosen aren’t a big Swiss tradition). But, of course, Austria has a huge military history, a fair bit of it involving us.

In many ways, Austria is one of those countries that some Brits might think we’ve invaded more than we actually have. After all, it’s a part of the world that was on the opposite side to us in both world wars. But in reality we also spent a lot of time fighting on the same side as the Austrians prior to the twentieth century. And it’s quite a long way away from both Britain and from the sea.

In the First World War, in a little-known part of our war, we had divisions fighting the Austro-Hungarian army, but almost all the fighting was done on Italian soil. By the armistice, which in this region was on 4 November 1918, not 11 November, our 48th South Midland Division had pushed to a position 8 miles north-west of a place then in Austria, called Löweneck. But when borders changed after the First World War, the area went to Italy and its name today is Levico.

In the Second World War, once again our troops were mainly approaching Austria from Italy (the main push into Austria from the west being conducted by US troops). This time we arrived in Austria just about the time the war ended. The big British push into Austria began on 8 May 1945 with 6th Armoured Division leading and Klagenfurt a major objective.

Having said that, after 8 May our troops moved in force into Austria. A lot of people have heard of our post-war presence in Germany, but our occupation of Austria isn’t so widely known. In July 1945, Austria was split into four zones, one each for us, the Americans, the French and the Soviets. We got Carinthia, East Tyrol and Styria. Vienna was similarly divided, plus the centre of the city was a separate zone under combined control. We had troops in Austria all the way through until 1955, enjoying the outstanding scenery. And perhaps, on occasion, the lederhosen.

Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan, found in the Caucasus with the Caspian Sea to the east, is one of those countries that is so far away from us, so far away from the open seas, and so far from what we tend to think of as our normal zones of influence that you may think we can’t possibly have invaded it. But if you think that, you’d be wrong.

By mid-1918, after the Russian Revolution, the Caucasus was a surprisingly confusing place. We tend to think of control of oilfields as a modern strategic goal, but already by that time, control of Azerbaijan’s oilfields was vitally important. A surprising number of players were competing for control of the oil, and for control of the Caucasus more widely. Obviously there were the locals and the Russians, but there was also, with the Ottoman Empire still in the First World War at this stage, the Ottoman Third Army trying to push up from the south. There was (bizarrely since you wouldn’t expect Germans here, but then, to be fair, I suppose, equally you wouldn’t expect Brits either) a German Expeditionary Force, independent of the Ottoman forces, that had come across the Black Sea from the Crimea, heading for the region after Georgia signed the Treaty of Poti with Germany. And there was us, with the imaginatively named Dunsterforce, commanded by one General Dunsterville (Dunsterforce does sound a little more crisp and dynamic than Dunstervilleforce, and imagine being an army clerk having to write Dunstervilleforce all the time). This included British and other Empire troops and some armoured cars, which had arrived in the area from Hamadan in what is now Iran.

Their original goal to counter German influence in the region turned into a mission to seize and defend the oilfields around Baku. After a few problems with Bolshevik troops, they made it across the Caspian to Baku, but their problems had only just started. Once in Baku, they were caught up in defending the city against an attacking army of Ottomans (and their allies in the Caucasus). In the ferocious Battle of Baku, lasting from August into September, Dunsterforce was eventually forced to withdraw from Baku in a dramatic night-time evacuation under fire. Probably spectacular to watch, but not much fun to be part of.

But we weren’t gone for long. Elsewhere, the war was going very badly for the Ottomans, and by late 1918, with the Ottoman Empire defeated, it was the turn of Ottoman troops to pull out of Baku and for us to return. British troops under General Thomson arrived in the capital of Azerbaijan on 17 November 1918 and imposed martial law. Gradually we handed over control to an Azerbaijani government, and by August 1919 we were leaving Baku again.

Bahamas

Columbus was probably the first European to hit the Bahamas. From our point of view, things sort of started in 1629 when Charles I granted the islands to Robert Heath, Attorney-General of England at the time. It was a bit of a cheap grant in many ways, since Charles didn’t actually control them and the man who was awarded the grant doesn’t seem to have done anything with them either. So, not much of an invasion at that point.

Finally, in 1648, William Sayle seems to have turned up from Bermuda with some English Puritans to found a settlement called Eleuthera, Greek for ‘free’. A settlement on New Providence followed and in 1670 Charles II granted the islands to the Duke of Albemarle and five others.

But it all became a bit of a mess with pirates and privateers running rampant and foreign powers joining in the chaos. In 1702–03, Nassau was briefly occupied by the French and Spanish.

The British crown took over control of the islands in 1717 and stamped out piracy, but our grip was still pretty tenuous at times. Well, in fact, more than tenuous, because we lost the islands occasionally and had to get them back. The Spanish attacked in 1720; in 1776 US marines occupied Nassau briefly; and in 1782 the Spanish turned up again and took control. At least this provided us with one really good story about invading the Bahamas.

The main character in the story is one Andrew Deveaux, who had an extraordinary career. He had been born in Beaufort, South Carolina. When the American Revolution came, he had originally joined the American rebels, but then had reverted to the loyalist side. He’d been given the rank of colonel by the British and raised a force of irregulars to fight for them. The traditional account is that when the Bahamas fell to the Spanish in 1783, he set off from St Augustine, Florida, with only seventy men to recapture the islands. He recruited another 170 men to his cause in the Bahamas themselves, and so with only 240 men, and even fewer guns, he faced a much larger Spanish occupation force, yet managed to persuade the Spanish commander Don Antonio Claraco Sauz to surrender.

The Bahamas became independent in 1971.

Bahrain

We have, of course, long had contact with the Gulf States, among them Bahrain.

In the early days, one of our main priorities was combating sea raiders in the area. So in 1820 the East India Company got the sheikhs of Bahrain to sign an anti-piracy treaty.

By 1861, we had also prevailed on Bahrain to sign a treaty which gave us control over its foreign affairs in return for protection.

But still we weren’t always entirely happy with the way everything was going here, and in 1868, after a conflict between Bahrain and Qatar, the gunboats Clyde and Huge Rose of Her Majesty’s Indian Navy destroyed the fort at al-Muharraq in Bahrain. In 1869, British gunboats were sailing into Bahrain to change rulers and put 21-year-old Sheikh Isa into power.

There were further treaties in the late nineteenth century between Britain and Bahrain. Bahrain became fully independent in 1971.

Bangladesh

Bangladesh consists of the eastern part of what used to be undivided Bengal. The western part is now in India and some of the key events in the history of Britain taking control of the territory that is today Bangladesh took place in modern day India.

As early as the late seventeenth century we were trying to take control in Bengal. But failing.

In 1620, the East India Company had a presence in Bengal, and in 1666 it set up a base in Dhaka. In 1682, William Hedges from the East India Company arrived in Bengal to talk to the Mughal governor there. Hedges was looking for trading privileges, but negotiations got a bit difficult and an English fleet arrived under Admiral Nicholson. What followed is sometimes called Child’s War (not much to do with kids, more to do with Sir Josiah Child, head of the East India Company) or the Anglo-Mughal war. But Child’s War wasn’t child’s play (see what I’ve done there?). It lasted from 1686 to 1690, during which we seized ships and bombarded towns. In the end, though, we lost and had to make concessions to the Mughal emperor, and pay compensation before we could re-establish commercial operations.

By the middle of the eighteenth century we were ready to have another go. In 1756 the new, young nawab of Bengal, Siraj ud Daulah, decided to exert control over the British base in Calcutta (Kolkata) in what is now West Bengal in India. With overwhelming forces he quickly captured it. In response, Colonel Clive and Admiral Watson were sent with the aim of re-establishing the British presence and getting reparation for its losses. After fighting outside Calcutta in January 1757, a peace deal was signed, and we turned our attention to the French, and not in a friendly way, attacking the town of Chandannagar, north of Calcutta. Chandannagar fell, but now Siraj ud Daulah started negotiations with the French, while we started secret negotiations with one Mir Jafar with the aim of replacing Siraj ud Daulah. Then Clive set off with a force to confront Siraj ud Daulah. The two armies met at the Battle of Plassey, or Palashi, in June 1757. Siraj ud Daulah had French help, but he lost. Clive then made Mir Jafar nawab, and when he got too close to the Dutch for our liking, we made Mir Qasim nawab instead.

Victory over Mir Qasim’s army and other allied forces at the Battle of Buxar in 1765 gave the East India Company control over Bengal in many ways. In 1793 the company took control of judicial administration in the territory as well.

William Heath had attempted to take control of Chittagong for the East India Company as early as 1688. In 1766 the company finally took control of the city. We were also given control of areas around Chittagong in the east of what is now Bangladesh, and a period of prolonged fighting followed against the region’s Chakma kings. The Chittagong Hill Tracts became an area where British control faced assorted challenges and was not always solid.

We left Bengal in 1947, when part of it became East Pakistan. The country became independent as Bangladesh in 1971.

Barbados

Barbados means ‘the bearded ones’, though nobody seems to know quite which bearded ones are being referred to, whether it was bearded locals, or the bearded fig tree that grows on the island, or something else. Bearded something anyway.

Our history of invading Barbados isn’t a hugely complex and dramatic one. The first English ship arrived here in 1625 under one John Powell and about two years later his younger brother turned up and started a settlement. And from then on it was basically under English and then British control until independence in 1966.

In fact, the only time we invaded it after 1625 was when we invaded it against ourselves, if you see what I mean. It sort of got sucked into the heavily armed disagreement, or civil war, that we had at home, starting in 1642. In the period after the execution of Charles I in 1649, bucking the trend in England, Royalists took over control of the government of Barbados, with the exception of the governor who stayed loyal to Parliament. So in 1651 the English Commonwealth sent an invasion force under Sir George Ayscue, and after a bit of fighting the Royalists surrendered. Invasion completed and succeeded.

Belarus

Big country, but unhelpfully for us, from the invading point of view, it doesn’t have a coastline and because of that, and assorted other quirks of history, we’ve not had that much to do with it militarily. If you know otherwise, let me know.

As far as I can work out, the closest we’ve got to invading Belarus is an assortment of English knights who led expeditions to fight alongside the Teutonic Knights in the fourteenth century. At the height of their power, the Teutonic Knights extended their control as far inland as Grodno in Belarus, so it’s possible some of our lot may have made it that far as well. Certainly some were active in besieging Vilnius (see Lithuania), which isn’t much more than 20 miles from the border with Belarus.