Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

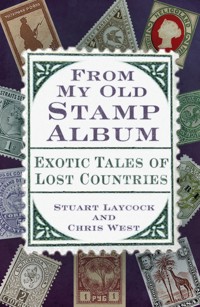

Pickup an old stamp album and flick through it. You'll find a host of exotic and unfamiliar names: Cyrenaica, Fernando Poo, Fiume, North Ingria, Obock, Stellaland, Tuva, – distant lands, vanished territories, lost countries. Do they still exist? If not, where were they? What happened to them? From My Old Stamp Album goes in search of the truth about these and many other amazing places. Stuart Laycock and Chris West unearth stories of many kinds. Some take you to long-disappeared empires; others throw light on the modern era's most pressing wars. You are invited to enjoy them all, in a collection of historical narratives as broad and enticing as that old stamp album that you've just discovered in the attic.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 410

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2017 as Lost Countries

This paperback edition published 2023

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Stuart Laycock and Chris West, 2017, 2023

The right of Stuart Laycock and Chris West to be identified as the Authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75098 680 9

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Introduction

A note on ‘Stamp-speak’

Alaouites and Hatay

Allenstein and Marienwerder

Amoy

Austrian Italy

Azad Hind

Batum

Biafra

Bohemia and Moravia

Canal Zone

Cilicia

Confederate States of America

Cundinamarca

Cyrenaica

Danish West Indies

Danzig

Dedeagh

Don, Kuban Republic, United Russia

East India Postage

Eastern Rumelia

Epirus

Federation of South Arabia

Fernando Poo

Festung Lorient

Fezzan

Fiume

French India

French Territory of the Afars and Issas

German Austria and Carinthia

Great Barrier Island Pigeongram Agency

Heligoland

Herceg Bosna

Hyderabad

Icaria

Inini

Italian Social Republic

Katanga and South Kasai

Kiautschou

Kurland

League of Nations

Manchuria Manchukuo

Memel

Moldavia and Wallachia

North Ingria

Nossi-Bé

Nyassa Company

Obock

Patiala and Nawanagar

Quelimane

Rhodesia

Río Muni

Ryukyu Islands

Saar

Sedang

Senegambia

Serbian Krajina

Shan States

Siberia, Far Eastern Republic and Priamur

Silesia

Slesvig

Sopron

Spitsbergen

Stampalia and the Dodecanese

Stellaland

Straits Settlements

Thurn und Taxis

Tibet

Transcaucasian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic

Trans-Juba

Transkei, Bophuthatswana, Venda, Ciskei

Tripolitania

Tuva

United Arab Republic

United States of the Ionian Islands

Upper Yafa

Victoria Land

Zapadna Bosna

Appendix: The Story of Stamp Collecting

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Many of us have them sitting in drawers or attics – old stamp albums that we filled eagerly as children, or that our parents or relatives did. Many of these will have attractive covers, which themselves will speak of bygone times (the one shown opposite comes from the turn of the last century). Inside the older ones, there will be adverts in once-fashionable typefaces for cheap packets of ‘assorted foreign stamps’ or for ‘philatelic accessories’ (where would any self-respecting Edwardian collector have been without a Lincoln Transparent Perforation Measure?)

Then there are the stamps themselves. These can be objects of great beauty. They can, if you are lucky, be valuable, though most aren’t. But where are these stamps from? Among the familiar issuing places, you will probably find ones you have never heard of. What and where were Cundinamarca, Fiume, Dedeagh or Fernando Poo? What happened to them and their people? Old stamp albums hint at fascinating stories.

This isn’t a comprehensive history of every country, island, colony, territory or city state that once produced stamps and no longer does. That would be a rather bigger book. Instead, we have set out to find some of the most fascinating of these and to investigate their past. A few still exist under the same names, though they no longer issue their own stamps. A few still exist and issue stamps, but under different names. Many no longer exist at all as independent entities, except in the pages of history and, of course, of old stamp albums.

Their stories include tragedy, drama, glory, despair and comedy. They often shed light on why parts of the modern world are as they are; places that few people have now heard of can prove to be missing jigsaw pieces that, when found, help make sense of much bigger pictures.

Any stamp from an entity that no longer exists has poignancy to it. Optimistic new countries used stamps to announce their arrival on the world stage. Imperial powers used them to stake their claim to legitimacy in their colonies. A stamp meant that the issuer believed that they were here to stay. Things didn’t always work out quite like that, however, as many of these stories show. Above all, perhaps, an old stamp album is a witness to the perpetually changing patterns of power that make up history.

If you try to acquire other official items from many of these lost entities, you may have to search long and hard and pay substantial amounts of money. But often stamps can be bought for very little. We hope you enjoy reading the amazing stories in this book as much as we enjoyed researching and writing them. If it prompts you to go and acquire a few of these remarkable paper scraps of history yourself to hold in your own hands, then that would be an added pleasure.

A Note On ‘Stamp-Speak’

Stamp collecting abounds with technical terms. We shall keep their use to a minimum, but a few will crop up in the text. First is the word philately itself, which is neatly defined as ‘the collection and study of postage stamps’ (thus giving it two totally separate meanings!). There is an implication that a philatelist is a rather serious collector.

Stamps essentially come in two conditions, mint (unused) and used (they have been on an envelope that has gone through the post). With older issues, mint stamps tend to be more rare and thus more valuable. With some modern issues, this is not the case, as many postal authorities have realised that collectors are a source of revenue, and produce ‘collectable’ stamps, which are sold straight to them. Few actually get used in the post. Few are worth much, either.

Stamp issues can be classified into two types, as well. Definitive stamps are the everyday ones, always on sale at your post office. Since 1967, UK definitives have been based on a ‘low relief’ bust of the Queen by sculptor Arnold Machin, a design classic that hasn’t aged over four decades. Commemorative stamps are issued to celebrate particular events or anniversaries, or just to create a nice series for people to use (and, of course, collect). They are only on sale for a short time. The term ‘commemorative’ gets stretched somewhat. The year 2016 saw a commemorative issue for the 350th anniversary of the Great Fire of London, but also one featuring landscape gardens. Logically, the gardens stamps weren’t ‘commemorating’ anything, but that is what they are called.

Any writing on a stamp is usually referred to as the inscription, and any visual element as the image. The value of the stamp (for postal use), almost always stated on it, is the denomination.

Overprints are when an extra layer of text or graphics is added to an existing stamp issue by the postal authority. For example, in Germany in 1923, prices roared up faster than new stamps could be produced, so old ones simply had new values printed on them. Examples include a 40 Mark stamp overprinted ‘8 thousand’ and a 5,000 Mark stamp overprinted ‘2 million’.

Overprints are often the first stamps a new government can issue: it takes time to design and print new stamps, but new regimes don’t want reminders of the old order dropping onto people’s doormats. For example, after the overthrow of the Portuguese monarchy in 1910, that nation’s old stamps were immediately overprinted with ‘Republica’. Colonial powers sometimes just issued general-purpose colonial stamps for their entire empire and overprinted the name of each particular colony for local use.

Overprinting is not the same as the postmark on a stamp, which is a cancellation mark put on every item sent through the post by the postal service, to stop the stamp being reused. It also often provides information about when and where a letter was posted: postmarks have been the key to many a classic murder mystery.

Finally, when is a stamp-like piece of paper officially a proper stamp? There is a debate about this, usually decided by the magisterial, six-volume Stanley Gibbons ‘Stamps of the World’ album (or by the Scott Catalogue if you live in the USA). Stamps not listed in these are known as Cinderellas. Some have wonderful stories, and have sneaked into this book.

Alaouites and Hatay

THE TRAGEDY OF the Syrian Civil War has recently focused much attention on the complexities of Syria’s more recent political and cultural history. Stamps cast an interesting light on some of it.

Syria, of course, has a long, varied and rich history. Damascus is often quoted as the oldest inhabited city in the world, and the area has seen a vast cavalcade of invaders come and go. Some of them are well known: Egyptians, Assyrians, Persians, Alexander the Great, Romans, Arabs etc. Some of the invasions are rather less well known, like the attempt to build a Crusader empire stretching deep into Syria’s interior that was limited by the defeat of Bohemond of Antioch at the Battle of Harran fought somewhere near modern Raqqah. Or like the Mongolian invasions of Syria that hit the area a number of times in the thirteenth century.

However, by the beginning of the twentieth century Syria was a key part of the Ottoman Empire, which meant that in the First World War it would become a target for Allied invasion.

Ottoman advances into Sinai in the early part of the war were soon reversed, and by 1917 British and other Allied forces were advancing through what was then Ottoman-occupied Palestine. In autumn they took Beersheba and in December, in time for Christmas, General Allenby entered Jerusalem on foot.

The chaos caused by Germany’s Spring Offensive on the Western Front helped call a temporary halt to Allied advances in the area, as Allied resources and attention were firmly focused there. But in late summer Allenby once again had the opportunity to advance north. His forces scored a major victory at the Battle of Megiddo, in September 1918, fought near the site of a number of ancient battles and near the site of Har Megiddo, the hill of Megiddo, also known as Armageddon.

More victories for Allenby would follow, and also advancing against the Ottomans were the forces of the Arab Revolt with, yes, Lawrence of Arabia himself. Australian cavalry and Lawrence and the Arab rebels entered Damascus on 1 October. On 25 October, the advancing Allies captured Aleppo. Turkey had had enough. On 30 October it signed the Armistice of Mudros. Less than two weeks later Turkey’s ally Germany would also sign an armistice.

The question now for the Allies was what to do with the remains of the Ottoman Empire. The Arab rebels believed that their assistance to the Allied cause would ensure a new era of Arab self-rule was about to begin. In Syria they were going to be disappointed. Britain and France, however, had already pretty much agreed under the Sykes–Picot Agreement that Britain would get Palestine and France would get Syria.

A lot of locals were extremely unhappy about the situation. In March 1920, the Syrian National Congress declared Hashemite Faisal King of Syria. But in April, the San Remo Conference established a French mandate over Syria. In July, advancing forces clashed with Syrian forces at the Battle of Maysalun and defeated them. Shortly afterwards, French forces entered Damascus and started to implement the French mandate. Faisal himself ended up as King of Iraq after the British who were in control there decided that he would be handy to help them stabilise the situation there.

The French set about organising their mandate and split Syria into several entities. One area, centred on Beirut, where many Christians were concentrated, would eventually become the modern state of Lebanon. To the north of that was an area, centred on Latakia, where the religious community the Alawites were strong, that became the Alaouite state (French spelling for Alawite). To the north of that was another area, centred on the ancient city of Alexandretta, which became the Sandjak of, yes, Alexandretta.

The Alaouite state never issued its own stamps, but a series of overprints, first on French stamps, then on Syrian ones.

The separate Alaouite state would not last for the entire time of the French mandate in Syria. Responding to those who wanted to see a more unified Syria, the French first changed the entity’s name to Latakia and then, in 1936, as France negotiated a deal to help protect its presence in the area after the expiry of the mandate, it was incorporated again into Syria.

Tensions over the status of the Alawites would, however, re-emerge. Both the previous and current presidents of Syria and some key members of their administrations have been Alawite, and resentment by members of the Sunni community, which forms the largest religious community in Syria, has been a key element in the Syrian Civil War.

At the same time as they yielded ground over the Alawites, the French authorities were also coming under pressure over another part of the territory they controlled – the area to the north based around Alexandretta.

As well as others, the area contained a significant Turkish population, and Turkey’s new leader Mustafa Kemal Atatürk had never accepted that the region was part of Syria. He was determined that the international community would accept it as part of Turkey. He too had been planning for what happened after the expiry of France’s mandate in Syria.

Turkey pressed the League of Nations to get involved in the area it referred to as Hatay. In response, a new constitution was prepared for the territory and in 1938 it became the Republic of Hatay.

Hatay had its own stamps. As is often the case, in such instances the first ones (in early 1939) were overprints (on Turkish stamps), but proper Hatay stamps soon followed, an attractive set of fourteen denominations featuring four designs: a map of the republic, its flag, two stone lions from the ruins of ancient Antioch and (for the highest denominations) Antioch’s modern Post Office.

The Hatay Republic did not, however, have a long future ahead of it. In June 1939, with the international community’s attention focused firmly on the threat of war in Europe, and amid suspicions that France was siding with Turkey in the hope that it would side with France in any new major world conflict, the Hatay parliament voted to join Turkey. In July, the Republic of Hatay became the State of Hatay (the republic’s stamps were reissued as overprints celebrating this fact).

French forces would leave Syria in 1946 but even today, many Syrians do not regard the question of the status of Hatay as settled forever.

Somewhat bizarrely, the State of Hatay is the name of a key location in the movie Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade.

Allenstein and Marienwerder

ALLENSTEIN AND MARIENWERDER sounds like a particularly old and reputable company. In fact, these are the names of two eastern European cities. Or at least they were. The towns are now called Olsztyn, basically the Polish version of Allenstein, and Kwidzyn, which doesn’t sound anything like Marienwerder at all.

Olsztyn is a city in north-eastern Poland not far south of the Kaliningrad enclave, part of Russia situated on the Baltic coast but with no land connection to the rest of Russia. It was badly damaged during the Second World War but has been repaired and rebuilt, and today has some interesting sights, including a castle, town walls, a cathedral, some museums and a university.

As is not unusual for this part of the world, Olsztyn has a history that has seen it connect at different times with both German and Polish identities. The Teutonic Knights constructed a major castle there in 1334 and by 1353 the town that had grown up around it had developed sufficiently to get municipal rights.

The Teutonic Knights and the Polish Crown didn’t exactly get on with each other very well at the time. A series of wars took place between the two parties with varying fortunes for each, and Allenstein/Olsztyn occasionally got caught up in these. In 1466, a peace deal that ended the Thirteen Years’ War that had featured, yes, the Teutonic Knights and Poland, but also the Prussian Confederation allied to the Poles, put Allenstein/Olsztyn under the authority, ultimately, of the Polish crown.

However, the Teutonic Knights had not yet entirely finished with Allenstein/Olsztyn. In 1519, they were at war with Poland yet again and in 1521 they laid siege to Allenstein/Olsztyn. Fortunately for the inhabitants, and unfortunately for the Teutonic Knights, Allenstein/Olsztyn had a genius in charge of organising its defences, a certain Nicolaus Copernicus, mathematician, astronomer, economist, scientist, diplomat and generally a very useful chap to have around for a wide variety of reasons. The Teutonic Knights failed to take Allenstein/Olsztyn and after a while gave up and made peace.

The town had a nasty time with the plague and also a nasty time with some Swedes who insisted on sacking it during assorted wars. Then, in 1772, as Poland was divided yet again and Prussia expanded, Allenstein was made part of the Kingdom of Prussia. And in 1871, with the declaration of the German Empire, it became part of Germany, which is where it still was as the first shots of the First World War were fired in 1914.

Marienwerder/Kwidzyn has in many senses a rather similar history to Allenstein/Olsztyn. It’s situated almost on the same latitude as the other place, but a little further to the west. Once again it’s the site of a major castle built by the Teutonic Knights, and once again the place got caught up in the series of wars between the Teutonic Knights and Poland. In 1440, it was the location for the creation of the Prussian Confederation, which would ally itself with Poland against the Teutonic Knights in the Thirteen Years’ War. Again, like Allenstein/Olsztyn, it would end up under the authority, ultimately, of the Polish crown after that war. And like Allenstein, Marienwerder would become part of the Kingdom of Prussia, as Poland was split up, and then part of the German Empire, where it too was, at the outbreak of war in 1914.

Almost as soon as the war had broken out, the Russians launched a huge invasion of East Prussia. However, in late August, German forces almost destroyed the Russian Second Army in one of the most decisive battles of the First World War. It prevented what could have been a vital Russian breakthrough in the east, even before the war had really got going. The battle was actually fought pretty much at Allenstein, and yet it has gone into the history books as the Battle of Tannenberg because the Germans were, for nationalistic reasons, keen to see the battle as revenge for the 1410 Battle of Grunwald or Tannenberg in which the Teutonic Knights were decisively defeated by Poles, Lithuanians and a variety of other east Europeans.

In the end, of course, victory at Allenstein/Tannenberg in 1914 would not prevent the defeat of Germany in 1918. And as the victorious Allies looked over the map of Europe and tried to decide how its borders should be changed, the question arose of what to do with Allenstein and Marienwerder, which were originally envisaged as being put in Polish territory. Should they become part of the new state of Poland that was being created, or should they remain part of Germany? In the end, it was decided that a plebiscite should be held. Allied commissioners and British and Italian troops entered the area in order to organise the plebiscite and the vote was held in July 1920 as the Polish–Soviet War was raging. The result of the plebiscite was strongly in favour of Allenstein and Marienwerder remaining in German territory. Which they did.

For the philatelist, Marienwerder is the more interesting of the two cities. A special stamp was designed for it, featuring the allegorical figure of a lady decked with various Allied flags, and with the inscription Commission Interallièe and the town’s German name. Fourteen different denominations, in different colours, were issued. A later issue changed the inscription to ‘Plebiscite’ and added the Polish name. Allenstein, by contrast, only managed overprints, on German stamps, one marked ‘Plebiscite’ and the other, intriguingly, ‘Traité de Versailles’.

The plebiscite is not the end of the story. By 1945, Germany had once again been defeated in a world war and the victorious Allies were changing borders in Europe. This time there would be no plebiscite. As the maps changed, Allenstein and Marienwerder would now be located deep inside Polish territory and be known by the Polish names Olsztyn and Kwidzyn. That is how they remain today.

Amoy

AMOY IS KNOWN to the modern world as Xiamen (pronounced ‘Sheeya-men’), a bustling port city 300 miles north-east of Hong Kong and at the heart of China’s modern economic miracle. Our word ‘Amoy’ comes from its name as spoken in local Hokkien dialect, Ē-mûi. It sits on an island known as Egret Island, from the birds that used to be found here in profusion, though the city has now spread onto the mainland, to which it is now joined.

Amoy has a full history. In the seventeenth century, a pirate rebel called Koxinga used it as a base for his attempt to drive out China’s new Manchu dynasty – he failed, but decamped to nearby Taiwan, from which he continued to harass the new dynasty until he was driven out by combined Dutch and Manchu forces.

In the early eighteenth century, Amoy became a major port, though it declined after 1757, when the Qing emperors decreed that all foreign trade (except for that with Russia) was made to be carried out through Guangzhou (Canton), where it could be more closely monitored under a system known as the Vigilance Towards Foreign Barbarian Regulations.

In 1842, the Opium Wars broke out. Britain’s role in these is not exactly elevating – maybe we deserved the title of ‘barbarian’. Essentially, we wanted to sell drugs to the Chinese; they tried to stop us, so we sent in gunboats. Guangzhou was the main target but we also sent a force to Amoy. The fortified city initially resisted the shelling, but when a land force tried to enter, on the morning of 27 August, it met very little resistance. The inhabitants had abandoned it in one night, having smuggled everything of value out of it in advance (gold items were hidden in hollowed-out logs). Just as well, as the invaders ransacked the city.

Under the Treaty of Nanking that followed this one-sided war, Amoy became a ‘Treaty Port’, one of five along the Chinese coast, where foreign merchants could do business with anyone they chose, selling whatever they chose. It began to boom again – Amoy’s inhabitants have a reputation for entrepreneurship. Foreigners were allowed to live in an international settlement where Chinese law did not apply. Amoy’s settlement was on Gulangyu Island. This still boasts magnificent colonial architecture. In the twenty-first century, it has become such a popular tourist attraction that visitor numbers are controlled. (150 years ago it was the British telling the Chinese they could not visit.) For a number of years there were only two such settlements in China: Gulangyu and the Concession in Shanghai.

Life in the settlement was run on Western lines. Churches, parks, schools and hospitals were built. Some of the schools specialised in music: Gulangyu Island still has more pianos per head of population than anywhere else in China.

There was also a Post Office. The settlement had its own postal system, which initially used stamps from Hong Kong or Shanghai. In 1894, Gulangyu’s Municipal Council – which now involved people from thirteen nations – decided to have its own stamps. A set was designed and printed in Germany. The stamps feature the same design, two egrets on a marsh, in different colours. The first ones carried denominations of ½, 1, 2, 4 and 5 cents. When the local post ran out of ½-cent stamps, the postmaster, John Philips, improvised, printing ‘Half Cent’ on 4- and 5-cent stamps. Stamps worth 3, 6 and 10 cents were later produced by the same method, and higher denominations were printed: 15, 20 and 25 cents.

There are also Postage Due overprints, for stampless mail arriving from Taiwan, which was then being invaded by the Japanese and where the postal system had broken down. These are the most valuable for the collector, especially the 2c blue.

An old stamp album will have spaces for the stamps of other Treaty Ports, too. Foochow (modern Fuzhou) is 200 miles up the coast from Amoy: its stamps feature a busy port, with Chinese junks, western sailing vessels and a ‘Dragon Boat’ used for races. Chefoo (modern Yantai) is in Shandong Province, about halfway between Shanghai and Beijing: its stamps (for some reason) feature a ‘smoke tower’ used for curing meat. Shanghai, of course, was the most successful of these ports, and issued a range of stamps.

These were all seaports. Your old album might well also feature spaces for later treaty ports that were founded along the Yangtze (Yangzi) River: Chinkiang (modern Zhenjiang), Chunking (now the vast city of Chongqing), Hankow, Ichang (Yichang), Kewkiang (Jiujiang), Wuhu and Nanking (Nanjing). Perhaps the most evocative of these are from Hankow: most of the Treaty Port stamps have a romantic feel to them, showing China as an exotic place. On Hankow’s stamp, a coolie lugs two huge loads over his shoulder – the reality of life for most of China’s inhabitants at the time.

But back to Amoy … The port flourished in the new century. Between the wars, Gulangyu became known as a place to party for Westerners and wealthy Chinese. However, this lifestyle was rudely interrupted by the Imperial Japanese Army, who invaded the island the day after Pearl Harbour. And after the war, it was not long before the Communists came in 1949.

In that year, China’s former ruler, Chiang Kai Shek, fled, as Koxinga had done, to nearby Taiwan. Xiamen, now called by its Mandarin name, became a focal point for tension between the two Chinas. The Jinmen (Quemoy) and Matsu islands are only a few miles off Xiamen, but are claimed by Taiwan. In 1954, Chiang began garrisoning large numbers of soldiers on them, intending to use them, so it seemed to the authorities in Beijing, as a stepping stone to an invasion. Mainland China responded by bombarding the islands. Taiwan had a defence pact with America, and in September, the US Joint Chiefs of Staff recommended using nuclear weapons to retaliate. President Dwight D. Eisenhower thought otherwise. However, the sabre-rattling from the US continued, and in the end the mainland Chinese ceased the bombardment. A second, similar crisis followed in 1958. After this, the bombardments continued, but only in the form of propaganda leaflets. There would also be the occasional commando excursion (by either side) to kill sentries or indulge in a little sabotage.

Mainland China’s dictator Chairman Mao died in 1976; in 1978 Deng Xiaoping came to power. Deng understood the need to ditch Mao’s extreme ideas and create a modern economy. He did so slowly – it was an enormous cultural change. Xiamen was one of the earliest places for this to happen. In 1980, it became one of four Special Economic Zones, where economic decisions would be ‘primarily driven by market forces’ and where foreign firms would be encouraged to form ‘joint ventures’ with Chinese businesses.

Since 2016, relations between Taiwan and mainland have deteriorated, with Taiwan declaring ever more robustly that it values its independence and China insisting that Taiwan is still its property. In the last two years, China has carried out major military operations threatening the island state (and especially the Jinmen and Matsu Islands). There is renewed talk of an invasion. For many years, Xiamen/Amoy has been quietly getting on with the business of making money. If such an invasion were to happen, the world’s spotlight would suddenly be on it again.

Austrian Italy

ONE THINKS OF Austria and Italy as two separate European countries, with very separate identities, but they have at times controlled – or aspired to control – chunks of each other’s territory. Austria had a long involvement with Italy via the Holy Roman Empire.

After the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, Europe craved peace. At the Congress of Vienna, its leaders got together and tried to draw boundaries that would last. As usual, what happened was that the most skilful and forceful diplomats got the best deals. One such man was Klemens von Metternich, the representative of the Austrian Empire.

Before the Congress, various parts of northern Italy had been ruled by Austria through various dukes. After it, these were lumped together into the Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia – a kingdom in theory; in practice a ‘crown land’ (in other words, part) of the Austrian Empire. It was a big territory. Lombardy is in the middle of the most northerly part of Italy, the area around Milan. Venetia no longer exists, but its former extent is similar to that of modern Veneto, the province at the top left of the Adriatic, of which Venice is the capital. A third modern Italian province, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, to the east of Veneto, was also part of this ‘kingdom’.

It was never very Austrian. Veneto had traditionally been part of the territory of the Republic of Venice. Lombardy had been under Austrian rule for a long time, but the culture was Italian.

As the nineteenth century progressed, new ideas came to the fore. Nationalism, and a sense that nations were defined by language and culture rather than whose army was biggest, became a liberal cause.

The year 1848 was the ‘year of revolutions’ all around Europe, especially central Europe. In Milan, it kicked off with a boycott of government monopolies (gambling, tobacco), which soon descended into street violence. Then in March, Metternich, who had become Austrian chancellor, was thrown out of office. Cue more unrest in Milan: five days of street fighting, during which several hundred people were killed. The Austrians retreated from the city and the Lombardy Provisional Government was formed. However, the Austrians regrouped, and next year won their territory back.

The Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia got its first stamps the year after that. There is nothing Italian about them at all, apart from the denomination, which is in local currency. Otherwise they were of the same design that Austria used throughout its empire, showing the Austrian coat of arms and bearing the inscription KK Post – kaiserlich und königlich, Imperial and Royal.

In 1858, special stamps for the delivery of newspapers in the kingdom were produced. Though only issued in Lombardy–Venetia, they were, again, totally Austrian, with the inscriptions in German and even the Austrian currency used. Three denominations were issued. The highest, the 4 Kreuzer, was bright red and featured the god Mercury. The ‘Red Mercury’ is now extremely rare: in 2015, one was sold for 40,000 Euros.

Despite Austria’s victory in what is now called the First War of Italian Independence, the momentum of ‘Risorgimento’, the move to create a united Italian nation, had merely stalled. A second War of Independence broke out in 1859, and this time the nationalists played a better game. Led by Count Cavour, who was prime minister of both Sardinia and Lombardy–Venetia’s neighbour Piedmont (the western part of northern Italy, around Turin), they allied themselves with a major European power, France. Cavour then goaded the Austrians into attacking him by organising large military manoeuvres near his border with Lombardy – an attack which brought the French into the conflict.

There were no French forces in Piedmont at the time, but their army was soon taken there by railway – the first time that this means of transport had played a major role in a war. Austria was defeated at the Battle of Solferino on 24 June 1859. The battle was a vicious one, with several thousand soldiers killed and 20,000 wounded. The businessman and writer Henry Dunant saw the aftermath, and went on to become a founder of the Red Cross. He was instrumental in drafting the Geneva Convention on the rules of war.

Solferino did not mean the complete end of Austrian rule in Italy. However, much of Lombardy now became part of the expanding ‘Kingdom of Sardinia’. Austria still controlled Venetia – and showed it by issuing more stamps. Again these were standard Austrian ones, made local only by the currency (the soldo and the florin were not used anywhere else in the Austrian empire).

Elsewhere in Italy, the country was uniting. By the end of 1860, it was effectively one nation – the Kingdom of Italy was formally proclaimed on 17 March 1861.

Venetia was still under Austrian rule, however – but not for long. The last stamps for ‘Austrian Italy’ came out in 1863. In 1866, Austria got into another war, this time with Prussia. Eager for Venetia, Italy allied itself to Prussia. Apart from Garibaldi’s ‘Alpine hunters’, the Italian forces did not distinguish themselves, but the Prussians did, and when peace was negotiated, Austria had to cede Venetia, first to France (Austria refused to hand it directly to Italy, because it did not feel that Italy had defeated it in battle), then to Italy. A plebiscite in Venetia in October of that year confirmed what everyone knew: the vast majority of the population wanted to be part of Italy.

The tension between the two nations continued into the twentieth century. In the First World War, Italy joined the Allies, and launched a series of mountain offensives against the Austrians. Fought in harsh conditions – avalanches were a perpetual threat – the battles, though vicious and costly, were mostly indecisive or led to small territorial gains for Italy (even after a victory, it is hard to sweep through mountain terrain). Then Germany entered on Austria’s side, and the tide turned. In October 1917, they won the Battle of Caporetto – during which poison gas was used – and advanced into Italian territory. Overprint stamps for the newly occupied region were issued.

However, the British and French then joined the Italians and stopped the advance. In 1918, Germany withdrew much of its support, needing to concentrate its resources on the war in France. The Austrian forces were defeated at the Battle of Vittorio Veneto and driven back. After the war, the current borders between Italy and Austria were drawn.

Azad Hind

AZAD HIND MEANS Free India. It was the name taken by the Indian government-in-exile set up by the Japanese in occupied Singapore in 1943. Its aim, as one would expect, was to end British rule in the subcontinent.

The Japanese had begun trying to subvert the loyalty of Indian servicemen before the outbreak of war. In late 1941, Mohan Singh, a former captain in the Punjab Regiment, agreed to lead an ‘Indian National Army’ (INA) of deserters. As the Japanese swept through Malaya in late 1941/early 1942, rather than being treated as prisoners of war, captured Indian troops were put under Singh’s command.

When Singapore fell on 15 February, over half the 80,000 captured defenders were Indian. They were offered the chance to serve under Singh and fight alongside the Japanese. Many accepted. At its height, the INA numbered 35,000 men.

Singh soon found himself at loggerheads with his new masters, however – he wanted his army to be autonomous, but the Japanese insisted that they must retain overall command. He was removed from power and arrested. Instead of simply replacing him with another, more compliant, commander, the Japanese built a political structure around the new army. It needed a ‘government’ to serve, and this government should be Indian. How much autonomy that government would have, of course, would be a different matter …

Enter Subhas Chandra Bose. Bose had been a senior member of Congress alongside Gandhi, but had no time for the latter’s non-violent methods. He had been under house arrest in India, but in 1940 he escaped, via a dramatic trek across Afghanistan, to Germany, from which he broadcast propaganda for his new hosts and began recruiting Indian soldiers captured by the Germans to fight against the British in India.

Around 3,000 signed up, swearing, ‘I will obey the leader of the German race and state, Adolf Hitler, as the commander of the German armed forces in the fight for India, whose leader is Subhas Chandra Bose.’

The aim was that these men would be parachuted into India – but before this could happen, Hitler invaded Russia. Bose, a Communist sympathiser, was dismayed. He quit Germany, leaving his legion leaderless – they were subsumed into the German army – and made his way, first in a German submarine then in a Japanese one, to Japanese-occupied Sumatra. Here, he was given a new role: to lead ‘the Provisional Government of Free India’, the political leadership of the Indian National Army.

A theme running through this book is the role of stamps in asserting the legitimacy of a political entity. Bose understood this well. His new government issued its own currency (a central bank was set up in 1944), had its own courts – and issued stamps (though, as we shall see, they were never used).

The stamps, designed and printed in Germany, range in value from ½ Anna to 1 Rupee. Designs show rural life (a peasant ploughing a field beneath a range of mountains), a nurse, a map of India with a chain breaking across it, a Sikh solider firing a German MG 34 machine gun, and three soldiers under the Azad Hind banner. Apart from the last of these, the stamps were printed in simple, clear monochrome. The last one is mainly black, but the orange and green of the banner also feature. This stamp is also much rarer, as only 13,500 were printed.

Some feature a surcharge: these are the ones intended for use in parts of India occupied by the Japanese. The Japanese did effect such an occupation (see below) – but the stamps did not get used.

No way could be found of getting them from Berlin to Singapore or to Port Blair, capital of the Andaman Islands, so they actually sat the war out in the Reichsdruckerei.

As Japan conquered formerly Indian territory, Azad Hind was given formal control over it. This mainly meant the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, two archipelagos in the Bay of Bengal (actually much nearer Burma than India), where an INA major-general, A.D. Loganathan, was made governor. However, he soon found out that he had no real power. The Imperial Japanese ran the place and soon began to exhibit the brutality that they showed to all other subject people. The vicious circle common to inept, authoritarian governments followed: ‘spies’ and ‘traitors’ were blamed for inefficiencies, given show trials and executed (forty-four of them on one day, many of whom had been supporters of the new administration but who had expected genuine independence). Forced labour was used in the construction of military projects like a new airport. There are stories of women forced into prostitution.

The islands were only reconquered in October 1945. Meanwhile, of course, Imperial Japan had been defeated. On that defeat, Bose, based in Singapore, had tried to flee to Russia, but was killed in an air crash in Taiwan. Naturally, conspiracy theories abound, some of which say he survived. The truth seems to be more prosaic. The plane was overladen to start with, and then developed engine trouble. Nobody survived. The Indian National Army and Azad Hind, featured on its confident stamps, died with him.

People still argue about the legacy of Azad Hind. In modern India, Bose is seen by many as a freedom fighter. Two stamps were issued in 1964 to celebrate the sixty-seventh anniversary of his birth (quite why such an odd figure was chosen, we don’t know), and another one in 1968 to commemorate the twenty-fifth anniversary of the founding of the Azad Hind government. A popular film in 2005 celebrated him as The Forgotten Hero.

On Andaman and Nicobar, however, people disagree. To them, the Azad Hind administration failed its own people. It seems hard to use the term ‘freedom fighter’ for Bose, who propagandised for Hitler, fought for the people responsible for the Rape of Nanking and, when they were beaten, tried to run to Stalin for support. But such is history. What you see, and certainly what you make of what you see, at least partially depends on where you stand.

Batum

UNLIKE MANY OF the locations in this book, Batum is still a name you can find on the map today. On the eastern shores of the Black Sea coast, a short distance north of the Turkish border, is situated Batumi, a port and the second-largest city in Georgia. It has beaches and modern skyscrapers but the region also has a long, long history.

In ancient times the legendary land of Colchis, home to the Golden Fleece, was located in this area. Home to the Golden Fleece that is, until, according to the legend, one Jason turned up with his Argonauts and nicked the fleece after seducing Medea, the daughter of the King of Colchis. Ancient Greeks were among the first foreigners to descend fully armed on the region, but far from the last. For instance, in the fifteenth century a bunch of Burgundians who were far, far distant from Burgundy, under the command of one Geoffroy de Thoisy, himself a knight of the Burgundian Order of the Golden Fleece, made an attempt to raid the region, only to find themselves ambushed, with Geoffrey taken prisoner.

In ancient times, the area lay on the border between the Roman Empire and the lands to the east, and later it would lie near the boundary between the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire. Which is just about where the British come in. Because yes, even though Batum is situated deep in the Caucasus, thousands of miles from Whitehall, it was the British who secured Batum’s place in stamp albums and stamp catalogues across the world.

Russia basically won the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78 and as part of the peace deal that ended the war it sent its troops into Batum. As the Caucasus oil boom took off in the late nineteenth century, Batum became a key component in the infrastructure of the area, with a railroad and oil pipeline running from Baku, on the Caspian Sea across the Caucasus to Batum from where oil and its products could be shipped elsewhere.

But the region was about to see changes, big changes. The same year that Russian troops entered Batum, to the east, was born one Iosif Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili. He is rather better known by his alias, Stalin, the man of steel.

In 1901, early in his revolutionary career, Stalin got a job at an oil refinery in Batum. After a fire, he led strikes at the plant which eventually led to his arrest. In 1903, he ended up in Siberia.

But, of course, this was not to be the end of attempts at revolution in the Russian Empire. In 1914, with the outbreak of the First World War, Russia joined the Allies, with Turkey siding with Russia. The Caucasus became a war zone again. Russia scored some successes in the war, but the cost in men and money was dreadful, and it suffered many defeats as well. In early 1917, the February Revolution (actually in March by the current calendar) led to the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II. The later October Revolution (actually in November by the current calendar) of the same year saw the Bolsheviks come to power. In March 1918, desperate to relieve themselves of the burden of war against Germany and its allies, the Bolsheviks signed a peace deal at Brest-Litovsk. Under its provisions, Russia gave up claims to Batum, and in April, Turkish forces moved into the city.

However, Turkish dominance of the region was to be short-lived. By October of that year, with German forces starting to collapse on the Western Front, it was Turkey that found itself looking for an exit from an unwinnable war. On 30 October, the Armistice of Mudros was signed and Turkey was out of the war. But war was definitely not at an end in the Caucasus.

Local nations, including Georgia and Armenia, took the opportunity presented by the collapse of the Russian Empire to declare independence, and fighting followed as new states battled to define borders in a chaotic regional mix that also included Turkish forces, German advisers, Red Russian forces and White Russian forces. Then into this violent, confusing and rapidly evolving regional situation strode the British. The British government thought intervening in the area would be a good idea. It wasn’t.

British forces seized the oil-rich areas around Baku and, in December 1918, Britain also sent troops in to seize Batum. General James Cooke-Collis became Governor of Batum. Just like British intervention elsewhere in the chaos that followed the collapse of the Russian Empire, British intervention in Batum achieved very little. One of its few lasting achievements, in fact (apart from instilling in the Soviet government a long-term suspicion of British intentions) was to get Batum listed in stamp albums. By February 1919, the city was running out of stamps. It was also running out of quite a lot else, but at least stamps were something the British occupation force could do something about. An attractive set of six stamps was produced, featuring an Aloe tree and inscribed Batumskaya Pochta in Cyrillic. Unfortunately, inflation set in, and various sets of overprints were soon needed, on both the ‘Aloe tree’ series and on Russian stamps. The latter are rare – but sadly also much forged, as are all Batum stamps. Buyer beware!

The end of British power in the Caucasus was not, however, far off. In the summer of 1920, British forces left the city and after being disputed between Turkish and Georgian troops, Batum finally came under control of Soviet forces, where it was to remain for many decades. Meanwhile in 1922, Stalin, the Georgian who had once led strikes in Batum, took control of the Soviet Union after Lenin’s death. Georgia would remain part of the Soviet Union until, after a referendum in 1991, it declared its independence.

Biafra

BIAFRA IS ONE of those names that is chillingly familiar for people who were adults during the 1960s. It is a name that they associate with pain, war and tragedy, a bit like people who were adults in the 1990s think of Bosnia.

Yet the name Biafra is an old one. It derives from the gulf off the coast of what is now Nigeria, called the Bight of Biafra (also called the Bight of Bonny). And for part of the 1850s and 1860s Britain had a Bight of Biafra Protectorate. Eventually it was merged with other territory into the Oil Rivers Protectorate. This had its own stamps, or at least British stamps overprinted with ‘British Protectorate Oil Rivers’. In 1893, these overprints were themselves overprinted with new values – these ‘double overprints’ are serious collectors items. The name subsequently changed to Niger Coast Protectorate, and this entity got its own stamps: two designs featuring an older Queen Victoria than ever appeared on British stamps.

However, it is what happened in 1967 that really brought the name Biafra to the world’s attention, and it is the reason its name is found in stamp albums and in this book.

In 1960, Nigeria became independent from Britain. By 1966, it was in turmoil as coup and counter-coup struck and ethnic tensions within the country erupted, particularly involving two groups, the Hausa, mainly located in Nigeria’s northern regions, and the Igbo, mainly located in the more prosperous east (which also contained much of the nation’s valuable resources of oil).

In September 1966, thousands of Igbo were massacred in Hausa regions and large numbers of Igbo fled to the Igbo areas in the east of the country. Some non-Igbos were then killed in the Igbo east or expelled from the area.

Peace talks in Ghana in early 1967 failed to reach a solution to the problems and, in May 1967, the head of Nigeria’s Igbo-majority Eastern Region, Lieutenant Colonel Odumegwu Ojukwu, with the support of a local assembly, declared the region independent as the Republic of Biafra. General Yakubu Gowon, Nigeria’s leader, refused to accept Biafra’s secession and by July the Biafra War, or the Nigerian Civil War, had broken out.

An initial federal ‘police action’ had little success and by contrast the early stages of the war saw some Biafran military successes. In August 1967, Biafran troops advanced into Nigeria’s mid-Western region.