20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

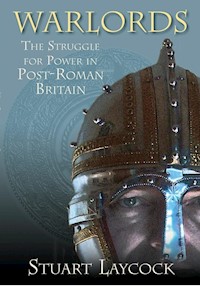

The centuries after the end of Roman control of Britain in AD 410 are some of the most vital in Britain's history - yet some of the least understood. "Warlords" brings to life a world of ambition, brutality and violence in a politically fragmented land, and provides a compelling new history of an age that would transform Britain. By comparing the archaeology against the available historical sources for the period, "Warlords" presents a coherent picture of the political and military machinations of the fifth and sixth centuries that laid the foundations of English and Welsh history. Included are the warring personalities of the local leaders and a look at the enigma of King Arthur. Some warlords sought power within the old Roman framework; some used an alternative British approach; and, others exploited the emerging Anglo-Saxon system - but for all warlords, the struggle was for power.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

To Clare, Freddie and Lizzy

Thanks to John Conyard and Comitatus for permission to use their photographs of late Roman re-enactment. Thanks to Robert Vermaat and Raymond’s Quiet Press for cover photographs.

CONTENTS

Title

Dedication

Introduction

1 Gerontius

2 Vortigern

3 Hengest

4 Ambrosius

5 Riothamus

6 Ælle

7 The Five Warlords of Gildas

8 Arthur

9 Cerdic

10 Edwin, Cadwallon and Penda

After Post-Roman Britain

Bibliography

Copyright

INTRODUCTION

Britain has kings but they are tyrants, and it has judges but they are corrupt. They spend their time terrorizing and robbing the innocent while protecting and promoting bandits and criminals. They have plenty of wives but also mistresses and lovers. They readily take oaths but perjure themselves. They make vows but they lie. They make war but the wars they make are unjust wars, wars against their own countrymen. They pursue crime in their lands but they also have criminals to dinner, cosying up to them, rewarding them. They give generously to worthy causes but in the meantime their crimes pile up, a towering mountain of guilt. They sit in judgement but rarely look for a just verdict. They despise the harmless and the humble but value above all the blood-soaked, the arrogant, the murderous, the adulterous – enemies of God who ought to be destroyed and erased from people’s memories.

(Gildas, On the Ruin of Britain, 27)

This is how the sixth-century writer Gildas describes the British warlords of his day, in an extraordinary passage (to be explored in more depth later) that gives the most graphic description of warlords in post-Roman Britain.

The picture Gildas paints of warlord character and behaviour is instantly recognisable to anyone who knows anything about warlords anywhere in the world, at any time from the dawn of history right up to today. And the fact that these characters were the celebrities of their day, their deeds relatively well known among their contemporaries, suggests that there is much truth in Gildas’ comments (if there wasn’t, then his readers would know). Having said that, Gildas is, of course, not even pretending to provide a totally balanced picture of these warlords, and it is possible to imagine that some of them might have been regarded with some affection by at least a proportion of their subjects – as ‘lovable rogues’ perhaps. Moreover, for all their failings in other areas, they were at least a source of basic protection in uncertain and violent times.

Gildas offers us no description of the appearance of post-Roman warlords. At the end of the Roman period and shortly afterwards they would presumably have looked much like any other late Roman commander. The late fourth-century ivory diptych shown in Figure 2 is thought to depict the late Roman general Stilicho, and his appearance is probably about as close as we can get to knowing what a British warlord of the late fourth or early fifth century would have looked like. He wears leggings with a richly patterned, long-armed tunic and a cloak secured by a large crossbow brooch. Around his waist is a belt from which hangs his spatha sword. In his left hand he supports a large round shield, with a spiked central boss. In his right hand he holds a spear. He wears no armour. (Interestingly, armour seems to have been worn less in the late Roman period than earlier, but the lack of armour in this carving may simply be because the subject is not shown in combat; he would certainly have worn a helmet in the field.) The fantastic gold buckle (3 ) from the late fourth-century Thetford Treasure, with a classical figure on the buckle plate and two horseheads forming the buckle loop, could well have belonged to a British equivalent of just such a figure.

Ivory carving probably showing the late Roman commander Stilicho.

However, Roman cultural influence faded markedly in the centuries after the end of Roman rule, particularly across large swathes of southern and eastern England, where new Anglo-Saxon styles came into fashion. The Sutton Hoo burial, thought to be that of Rædwald, king of East Anglia, gives us the richest example of what a post-Roman Anglo-Saxon warlord could have looked like. There are elements in this burial that link back to the Roman style (such as the basic form of the helmet, the standard, the golden shoulder clasps, plus of course, the Mediterranean silverware buried with him), but there are also whole new cultural references, such as the extensive use of inlaid garnets and glass in the Frankish fashion, the intertwined designs on the great gold buckle, and the Scandinavian mythological scenes on the helmet decoration. Of course, Rædwald (or whoever else it was buried under the mound all those centuries ago) was at the top end of the scale but many other warlords must have adorned themselves in a basically similar manner.

The Thetford buckle is a fine example of the buckles worn by rich and powerful figures in Britain at the end of the Roman period.

In regions beyond the reach of Anglo-Saxon culture at that time Roman habits persisted (particularly under the influence of the local church) but even here warlords were beginning to adopt some elements of non-Roman style. In these areas, though, the styles in question link not so much to continental Germanic kingdoms as to Ireland and pre-Roman British traditions. The period saw a resurgence of metalwork with swirling designs similar to those found in Britain in the pre-Roman period (the enamelled disks on hanging bowls of the period are among the finest examples), and the description of warriors in ‘Y Gododdin’, a poem describing events some time probably in the sixth century but written later, suggests that in some ways they resembled their pre-Roman ancestors (even if the word for chain mail, llurig, is derived from the Latin word lorica):1

Men headed for Catraeth with a battle-cry,

Fast horses and dark armour and shields,

Holding spears high, their points deadly sharp,

With shining chain mail and flashing swords.

(‘Y Gododdin’)

Helmets were probably not generally worn among pre-Roman Britons and it is interesting to note that helmets are never mentioned in ‘Y Gododdin’. By contrast helmets are regularly mentioned in the early Anglo-Saxon poem ‘Beowulf’.

Whether among Britons or Anglo-Saxons, the experience of combat in the fifth and sixth centuries would doubtless have been in many ways familiar to anyone time-travelling there from early first-century Britain.

The spears thrown by the noble commander,

As he charged forward, carved a broad path,

He was raised for battle with mother’s help,

While he aided others his sword slashed,

Spears of ash scattered by his strong hand…

(‘Y Gododdin’)

And if the post-Roman warlords’ appearance hadn’t changed much, neither had their pattern of warfare. Almost always their wars were waged against neighbouring warlords in Britain, but very occasionally they formed brief alliances to counter threats from overseas. In fact, recent research suggests that a re-emergence of patterns of tribal fighting in the power vacuum left by the collapse of Roman control in Britain at the end of the fourth century and in the early fifth century (as opposed to the situation in mainland Europe where new large-scale Germanic kingdoms immediately took over and in many ways maintained existing Roman administration) may well have largely been responsible for the ending of the complex Roman British economy and the disappearance of the Roman British lifestyle.2

As Tacitus put it, shortly after the Roman invasion:

In fact, nothing has assisted us more when fighting this mighty nation than their inability to work together with each other. It is only rarely that two or three states unite to repel a common enemy, and in this way, fighting separately, they are all conquered.

(Tacitus, Agricola, 12)

And Gildas made exactly the same point after the end of the Roman occupation:

For it has always been the way with our nation, as now, to be powerless in repelling foreign enemies, but powerful and bold in making civil war.

(Gildas, On the Ruin of Britain, 21)

The earliest British warlord, and indeed about the earliest named Briton of whom we have any record, is Cassivellaunus, who is primarily known for leading a British alliance against Caesar’s second invasion of Britain in 54 BC. However, it is clear from a reading of Caesar’s text that this alliance among the British tribes was very much the exception; in many ways it seems that Cassivellaunus was a sort of prototype of the British warlords described by Gildas some 500 or 600 years later. Caesar states that prior to the arrival of the Roman army Cassivellaunus had been at permanent war with his neighbours. He had also killed the king of a neighbouring tribe, the Trinovantes, after which the son of that king, Mandubracius, had fled to Caesar for support. The alliance that Cassivellaunus briefly led was quickly abandoned by the Trinovantes (perhaps not surprisingly under the circumstances) and also by a number of other tribes, including a tribe that Caesar describes as the Cenimagni, possibly a misinterpretation of the phrase Iceni magni, ‘the great Iceni’.

Coin referring to Commius, a warlord probably from Gaul.

The Romans, of course, regarded Britons collectively, lumping together all the people living on the island of Britannia, regardless of tribal differences, and Gildas had something of a similar view, either inherited from Roman sources or perhaps developed independently as a counter-weight to the developing Anglo-Saxon presence in Britain during his lifetime. However, the majority of Britons, both in the time of Cassivellaunus and in the time of Gildas, would probably not have regarded themselves as ‘British’. As far as nationality went, they would have thought only in terms of their tribe, or in the days of Gildas in terms of the kingdoms that developed on the basis of the tribal territories in the post-Roman period. Mandubracius would have seen himself as Trinovantian, not British, and he would not have thought of Cassivellaunus as a fellow-countryman in any real sense. It is in some ways rather similar to the situation in Europe today. Europeans today accept that they are European, a part of the wider European Union, but very few would define their nationality as European. They see themselves as British, or French, or Italian. British warlords in post-Roman Britain would have felt no loyalty to other British warlords from other tribal territories, and would have had no qualms about forming an alliance with an overseas power against other British tribal territories if they saw any advantage in such a move. It should be no more surprising for us to see the Trinovantes allying themselves with Rome against Cassivellaunus, than it is for us to see the Scots allying with France against England in the medieval period.

Coins of Tasciovanus showing warlike motifs.

It was not, however, just Romans who came across the English Channel in the first century BC. In an early demonstration of how power could translate across the Channel, a warlord from Gaul seems to have decided to set up shop in Britain as well. Commius is an interesting character. Caesar describes at some length his assorted military adventures as a leader of the Atrebates in northern Gaul. The last that is heard of him in Gaul, though, is that he had fled across the Channel to Britain. Shortly after this, the name Commius starts appearing on British coins in the area of a tribe that came to be known as the Atrebates. It is therefore assumed that this is the same Commius3 and (since there is no archaeological evidence for an extensive influx of foreigners and foreign culture into the area in question at this stage) that somehow Commius established a new political entity with a new name on the basis of an existing British political entity. Subsequent rulers of the area repeatedly describe themselves as COMF, short for ‘Commii Filius’ or ‘son of Commius’, pointing to the central role of this character in the creation of the area’s new identity. The Atrebates became one of the key tribal powers in pre-Roman Britain (probably even taking over the territory of the Cantii briefly), and, as we shall discuss later, probably in post-Roman Britain too.

However, there was another tribal superpower in central and southern Britain that was to outshine even the Atrebates in the struggle for power in pre-Roman Britain – the Catuvellauni. Cassivellaunus may well have been an early ruler of this tribe. According to Caesar, Cassivellaunus came from an area just north of the Thames and adjoining Trinovantian territory, which puts him pretty much in the same area as the Catuvellauni. Furthermore, the two names are sufficiently similar to wonder if Caesar might not have mangled the name of Cassivellaunus in the same way that he probably did with the name of the Iceni.

Coin bearing the legend ‘CARA’ and probably linked to Caratacus.

Tasciovanus and Cunobelin are two warlords who certainly do seem to have been instrumental in the rise of the Catuvellauni. The coins of Tasciovanus appear across a large swathe of central and eastern England, while those of Cunobelin spread even further, as Catuvellaunian influence seems to have expanded to include the entire territory of the Trinovantes and the Cantii, plus parts of the territory of the Iceni, Dobunni and Atrebates.4 Some scholars have argued that the adoption of Catuvellaunian/Trinovantian coinage across this large territory might simply represent some form of peaceful extension of influence. However, in the light of Caesar’s comments about the possible early Catuvellaunian ruler Cassivellaunus being constantly at war with his neighbours, and bearing in mind the warlike motifs on a number of the coins of Tasciovanus and Cunobelin (5), it seems more reasonable to see this as some form of conquest.

This interpretation seems to be confirmed by events in northern Atrebatic territory in the period before the Roman invasion under Claudius. Around AD 35 coins issued in the name of Epatticus appear in northern Atrebatic territory around Silchester. The coins reflect some elements of Atrebatic design but they also incorporate elements of Catuvellaunian design, and Epatticus describes himself, as Cunobelin also does on his coins, as a son of Tasciovanus. Subsequently Epatticus’ coins are replaced by coins of the same style but bearing the inscription ‘CARA’ (6).5 This legend may well refer to Caratacus, identified by the Roman historian Cassius Dio as Cunobelin’s son and a Catuvellaunian warlord. Then, shortly before the Roman invasion of AD 43, Cassius Dio describes a British king named Berikos fleeing to the court of Claudius to seek help in getting his kingdom back. Berikos is assumed to be Verica, an Atrebatic king who was issuing coins in the area to the south of that controlled by Epatticus and CARA. It seems reasonable to assume, therefore, that just before the invasion Caratacus and the Catuvellauni had expanded forcibly into wider Atrebatic territory, and perhaps even that Verica helped to bring about the Roman invasion by securing the Romans as allies and bringing them into Britain to fight the Catuvellauni.

And indeed, when the Romans did invade, it is clear that they were specifically targeting the Catuvellauni rather than Britons in general. They made directly for the capital of the Catuvellaunian/Trinovantian confederation at Camulodunum, with Caratacus’ brother Togodumnus dying in the process. As with Caesar’s second invasion back in 54 BC, there seems to have been no real question of British solidarity here. Many of the tribes probably instead hastened to ally themselves with the new power in British politics. Cassius Dio, for example, records some ‘Bodunni’ (a name widely assumed to be a mangling of Dobunni) who had previously been ruled by the Catuvellauni, quickly joining up with the Romans. We know that the Romans left British kings in power in Icenian and Atrebatic territory, and there is no reason to suggest they behaved much differently in other areas. Again, we should not be surprised by this. Other British tribes would have regarded the quarrel between the Catuvellauni/Trinovantes on one side and the Atrebates/Romans on the other as nothing to do with them. Out of sheer self-interest they would come to political terms with whichever side won. Both sides were foreigners to them, even if the Romans were foreigners from slightly further away.

Much more surprising, in fact, is that in a highly unusual development by British tribal standards, Caratacus, having managed to escape the Roman invaders, was able to persuade two tribes from what is now Wales, the Silures and Ordovices, to fight the Romans alongside him. It is hard to know how a Catuvellaunian warlord from central England managed to persuade tribes from so far away to take an interest in his war. However, personal charisma (Caratacus seems to have charmed the Senate too when he was finally taken to Rome as a prisoner), plus large amounts of valuables, may have had something to do with it. It seems, too, that after the Roman rampage through the territory of the Durotriges in Dorset, it had begun to dawn on some Britons that Roman rule might not be entirely such a good thing.

Even at this stage, however, there were still plenty of Britons for whom the idea of ganging up against the Romans, just because they came from across the Channel, seemed bizarre. When resistance among the Silures and Ordovices collapsed, Caratacus fled north to the territory of the Brigantes but their queen, Cartimandua, promptly handed him over to the Romans.

Most British warlords were, of course, men. Cartimandua, however, demonstrates that British women could be equally powerful. This, of course, was confirmed just a few years after the capture of Caratacus by the explosion into British and Roman history of Boudica, queen and war leader of the Iceni. Boudica has usually been portrayed as attempting to throw the Romans out of Britain but there is very little evidence to suggest that this is actually what she was trying to do. If one ignores the inevitably Romano-centric nature of accounts by Roman historians, Boudica’s actions look much more like those of a traditional British warlord. There was no concerted attempt to raise other tribes to rebellion, no concerted attempt to attack the Romans across the breadth of Britain. Instead, there was a great deal of looting and destruction in the territory of the Iceni’s main tribal rivals, the Catuvellaunian/Trinovantian confederation.6 It is true that Tacitus portrays the Trinovantes as the allies of Boudica, rather than her victims, but there are reasons to suppose that he may have got it wrong. After Boudica’s rebellion, for example, the Trinovantian royal compound at Gosbecks outside Colchester continued to be occupied presumably by some form of Trinovantian leadership, while the Romans seem to have allowed the Trinovantes to dig new defensive earthworks after the rebellion.7 Tacitus knew that the Roman colonia at Camulodunum, in Trinovantian territory, had been attacked and burnt, and perhaps simply assumed that the Trinovantes were in some way involved.

All in all, the history of Britain up to the end of the first century AD produces significant evidence of a large crop of British warlords in pursuit of power in Britain. And as we shall shortly see, in that respect (and quite a few others, as it turns out) the fifth and sixth centuries ad in Britain were much the same. In this book we shall see how ambitious men used a variety of strategies to achieve their goals. Some chose to seize power by working within the trADitional Roman power structure. Others chose a new route, working within an independent British context, and still others chose to work within the newly developing Anglo-Saxon power structures. In all cases, though, their goal was power.

Of course, exploring the history of the fifth and sixth centuries in Britain is always going to be a controversial process. Fifty years ago it was widely accepted that the surviving historical accounts of the period, including Gildas and Bede and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, could give a broadly reliable outline of what happened in Britain in the period around and after the collapse of Roman control. However, more recently that position has been almost totally reversed, with scholars becoming reluctant to accept the historical sources at face value; indeed, some dismiss them all as pseudo-history and demand evidence solely from archaeological sources instead, treating the period almost like prehistory.

Sadly, though, archaeology has not yet been able to replace the more traditional historical sources with a coherent and comprehensive narrative of what was actually happening in Britain in the crucial years. Instead the process of relying almost entirely on archaeology has to a certain extent stripped the English and Welsh nations of their birth stories, because interpreting the archaeological evidence for the period is proving just about as difficult and controversial as interpreting the historical evidence. So if the archaeology cannot supply all the answers on its own, then it seems sensible to look again at the traditional historical accounts in the light of new archaeological research, and see if it is possible to create from the two combined sources of information an understandable and broadly convincing new account of post-Roman Britain and of the men who dictated the course of its early history.

Notes

1 Gidlow, 2004, 132.

2 Laycock, 2008.

3 Though some coins marked Commius could belong to a younger successor also called Commius; see Cunliffe, 2005, 142, 169.

4 See Cunliffe, 2005 fig. 7.9 for a comparative distribution of the coins of Tasciovanus and Cunobelin.

5 See Cunliffe, 2005, 147 for these developments.

6 Laycock, 2008, 63–84.

7 Crummy, 1997, 86, 90.

CHAPTER 1

GERONTIUS

Gerontius must be one of the most influential Britons of whom nobody has ever heard. No, he’s not Elgar’s Gerontius and his dream, such as it was, was probably just one of power. He was a warlord who conquered Spain and Portugal with the help of British militiamen over a thousand years before Drake ‘singed the King of Spain’s beard’. He played a key part in the end of Roman rule in Britain and even, arguably, in the end of the Western Roman Empire, before dying with his wife in a blazing building surrounded by mutinous troops.

During the roughly three-and-a-half centuries that Britons were part of the Roman Empire, they played a distinctly low-key role in Roman political life. Other parts of the Empire such as Africa, Pannonia and Gaul produced a string of political figures who played a significant role in central Roman government, up to and including emperors. Britain, however, despite being the springboard for a number of attempts on the imperial throne (including those by the ill-fated Clodius Albinus at the end of the second century and the much more successful Constantine at the beginning of the fourth), produced throughout most of the Roman period few, if any, native sons or daughters who made a significant political impact in Rome. Two usurpers, the obscure Bonosus (c. 281) and the rather more successful and long-lasting Magnentius (ruled 350–353), both seem to have had British fathers – but equally both were born on the continent to non-British mothers.

The apparent reluctance of the British aristocracy to become involved in imperial politics, compared to their continental counterparts, may have much to do with the unusual nature of Rome’s occupation of Britain, when compared with the manner in which it controlled other parts of the Empire. Britain was the last major western territory added to the Empire. Parts of Africa, for instance, had already been occupied by Rome for almost 200 years by the time Claudius’ legions scrambled ashore on British soil. There had been a Roman province in the south of Gaul for almost as long, and it had been almost 90 years since Vercingetorix and his Gallic alliance had finally succumbed to Caesar. Britain, by comparison with most of the rest of the Empire, became Roman late and even then it was, in reality, only partially Romanised. We talk of the centuries of Roman occupation of (most of) Britain as ‘Roman Britain’, yet there was, in truth, nothing very Roman about much of Britain during this period. Southern, central and eastern areas do indeed show ample archaeological evidence of a widespread adoption of Roman lifestyles, but evidence of cultural Romanisation in Cornwall, Wales and north-west England is mainly restricted to ceramics, glass and a few trinkets. And the number of such artefacts becomes even smaller if we look further north. Scotland, of course, remained largely beyond Roman reach, both politically and commercially, which explains the scanty evidence there, but in Cornwall, Wales and north-west England the absence of evidence of Roman lifestyles must be seen, to some extent, as indicating a specific rejection of Romanisation. The inhabitants could have had access to a Roman lifestyle if they chose to. They did not.

Dragonesque brooches were made and worn in Britain well into the second century, showing a strong survival of British tastes and style under Rome.

Large parts of Britain, even where it was under Roman control, never adopted Roman culture. What’s more, even in the ostensibly Romanised centre, south and east of the island, it would be wrong to assume that the use of Roman items indicates that the locals had necessarily adopted a specifically Roman identity in addition to the trappings of the Roman lifestyle. In the same way, Britons today may wear American clothes, eat American food and listen to American music but none of this indicates that they see themselves as Americans.

As already touched upon, when the Romans took control of Britain in AD 43, they found an island occupied by a large number of different tribes, with different cultures, different backgrounds and maybe even, for all we know, different languages (or certainly very different dialects). Fighting between tribes and cross-border raiding were probably common phenomena. There was no such thing as a united British identity. The inhabitants of the island would have seen themselves as Catuvellauni, or Brigantes, or Dobunni, or Iceni, or Atrebates or any of a large number of other tribal identities. And the Romans did little to change this in the period after the invasion. Like all experienced imperialists, they wanted to control their new country with as little fuss and trouble as possible, and that meant, among other things, working with the existing traditional political structures rather than imposing a whole raft of new and different ones. In the Mediterranean regions where city-states had long been the building blocks of political life, the Romans gave them local political control, with each becoming on some level a smaller version of Rome itself. In Britain, where there were no city-states for the Romans to build on, they instead used the tribes as the basis for local government. The tribes became self-administering civitates (the Roman name for their key unit of local government) and the traditional British tribal aristocracies almost certainly largely remained in place as the leaders of these new civitates. A common feature of British archaeology in the early Roman period is the appearance of Roman-style villas near, or even on top of, significant pre-Roman dwellings, suggesting the widespread continuity of estates and land tenure from pre-Roman into Roman times. Even more significantly, there is plenty of evidence to suggest that Britons continued to see their national identity in terms of their former tribes, rather than gradually over the centuries coming to see themselves as ‘Britons’ or as Romans.

On a number of inscriptions from the Roman period we can see Britons clearly identifying themselves by their tribal nationality. A sandstone base at Colchester, for instance, carries an inscription referring to ‘Similis Ci(vis) Cant(iacus)’, a citizen of the civitas of the Cantii. A tombstone from South Shields records the nationality of Regina, wife of Barates the Palmyrene, as ‘natione Catvallauna’, ‘of the Catuvellaunian nation’ (8). A certain Aemilius, who had served with the Classis Germanica, is recorded on a tombstone from Cologne as ‘civis Dumnonius’, ‘a citizen of the Dumnonii’.1 References to individuals being British do appear on inscriptions, but these tend to be found not in Britain but on mainland Europe, where British tribal identities might, among a population largely ignorant of them, be expected to take a lower profile. Even at the end of the Roman period, just across the Channel one Sidonius Apollinaris identifies himself as ‘Arvernius’, one of the Arvernii, and his friend Aper as ‘Aeduus’, one of the Aedui. Similarly, many civitas capitals in Gaul abandoned their Roman names during this period and in common usage reverted simply to the name of the local tribe. Thus, for example, we have Paris (Roman Lutetia) from the Parisi, Avranches (Roman Ingena) from the Abrincati, Trier (Roman Augusta Trevorum) from the Treveri, and Vannes (Roman Darioritum) from the Veneti. In Gaul, however, any potential renewal of the expression of independent tribal identities was prevented by the introduction there of large Germanic kingdoms that directly took over from Roman control, and perhaps also by the more developed state of the Roman Catholic Church in Gaul at the end of the Roman period (as compared to the situation in Britain at the same time). If tribal identity could be so long-lived in Gaul, it would surely have been much stronger in a Britain that was Romanised later than Gaul and much less completely.

Inscription identifying a British woman as of Catuvellaunian nationality.

There is a sense also in literary references from the fourth and early fifth centuries that even after being part of the Roman Empire for hundreds of years, Britons were still seen as being somehow different and separate from the rest of the Empire. The poet Ausonius, for instance, composed a number of epigrams based on the assumption that being good and being British were mutually exclusive. Gildas also, writing perhaps 100 years after the end of Roman rule, shows no inclination to identify the British with people from the rest of the Empire. In his account of the arrival of the Romans in Britain and their departure he draws a consistently clear distinction between Britons and Romans. Perhaps it has something to do with Britain being an island. The rest of Western Europe seems to have adapted to inclusion in the Roman Empire with more enthusiasm. Perhaps we can see something similar today in the European Union. While countries like France and Germany, despite occasional gripes, seem happy enough to be integral members of the EU, Britain seems instinctively to want to keep itself separate. It remains a member of the EU, for the moment, because of the clear economic advantages from doing so, but one suspects that general British public sentiment remains deeply suspicious of the EU, even after decades of membership, and should the advantages of membership ever become less clear, there would doubtless be a serious push for the UK to leave, just as Britain was eventually to leave the Roman Empire in 409.

The pre-Roman tradition of conducting intermittent hostilities with neighbours seems to have continued into the Roman period. As mentioned in the Introduction, Boudica and her Iceni did not just attack Romans. They also targeted the Catuvellauni, a tribe with whom they may well have had long-standing border disputes (judging by the spread of Catuvellaunian coinage into formerly Icenian territory under Cunobelin, and by the digging of a probably pre-Roman defensive ditch, Mile Ditch, across the Icknield Way corridor near Cambridge).2 Equally, towards the end of the second century (in a move which has no contemporary parallel in other parts of the Empire) towns close to the borders around a number of British civitates (again including the Catuvellauni) were fortified, creating a defensive ring around these tribal territories. These defences are again suggestive of cross-border tribal raiding and should probably be linked to the appearance of two groups of villa and town fires identified within the territory of the Catuvellauni and Trinovantes. One of these groups of fires lies in the north-west of Catuvellaunian territory and, judging by the road layout in the area, could be linked to Brigantes raiding south from the Peak District. The second group lies in the Essex area and may be linked to Iceni raiding southwards from their tribal territory, just as they had under Boudica.3