Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

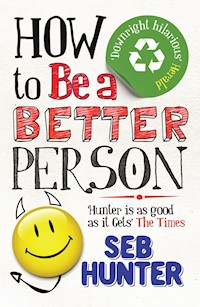

Why is it so difficult to find the time to help others? When Seb Hunter became aware of a nagging ache in the place where his soul ought to be, he embarked on a two year odyssey of volunteering - with hilarious results. He collects litter, teaches pensioners how to use the internet, works at Oxfam (where he meets Gladys, his septuagenarian nemesis), mans a steam train line, becomes a star DJ on hospital radio, visits prisoners, and runs a very long way for charity... But will his quest for self-improvement be successful? How to Be a Better Person is the tale of a cynic's attempt to become a better person by helping others. For nothing. It's a volunteering call-to-arms! Oh no it's not! Well it is, sort of...

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 411

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

HOW TO BE A BETTER PERSON

Seb Hunter is the author of two previous books, Hell Bent for Leather: Confessions of a Heavy Metal Addict (2004) and Rock Me Amadeus: When Ignorance Meets High Art, Things Can Get Messy (2006). He is one third of electroacoustic improvisation trio Crater, in which he plays guitar and electronics. He lives in Winchester with his wife and two young children.

www.sebhunter.com

Also by Seb Hunter

HELL BENT FOR LEATHER:

CONFESSIONS OF A HEAVY METAL ADDICT

ROCK ME AMADEUS:

WHEN IGNORANCE MEETS HIGH ART,

THINGS CAN GET MESSY

First published in trade paperback in Great Britain in 2009 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic, Ltd.

This paperback edition first published in 2010 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © Seb Hunter, 2009

The moral right of Seb Hunter to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Acts of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Some names have been changed.

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

978 1 84887 486 2 eISBN: 978 1 84887 486 2

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books An imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZwww.atlantic-books.co.uk

for Roo

By three methods we may learn wisdom. First, by reflection, which is noblest; second, by imitation, which is easiest; and third, by experience, which is the bitterest.

Contents

My house, Brentford, west London Tuesday afternoon, during Countdown

Step One

Step Two

Step Three

Step Four

Step Five

Step Six

Step Seven

Step Eight

Step Nine

Step Ten

Step Eleven

Step Twelve

Pledge Coda

Conclusion

The End

Exit

Organizational Contact Details

Thank You

My house, Brentford, west London Tuesday afternoon, during Countdown

The phone rang.

Unlike a lot of people, I like it when the phone rings; it might be something exciting: somebody with some money,1 or good news, or a friend inviting me down the pub, or my agent with heady news of lucrative foreign rights sales.2

Usually it’s none of those things; usually it’s someone in a call centre, often a call centre somewhere on the Indian subcontinent. Their name is Keith, even though their name’s not really Keith, it’s Tajinder, but the powers that be demand they anglicize their names to make you and me feel more comfortable. I hate these cold calls as much as the next person (every time I hang up I make a promise that I’m going to go ex-directory) but I always try to be polite and hear them out, before explaining firmly that I’m not interested in a free mobile phone or anything else thank you very much, sorry, no really, goodbye now, sorry again, cheerio, goodbye! I make it cheery so as not to make them feel rejected or bad about themselves. Then I feel bad about myself for five to ten seconds before getting on with whatever I was doing before, i.e. waiting for my agent to call with news of lucrative foreign rights sales.

So the phone rang and all this went through my head again. Maybe, at last, it’s someone with some money! I snatched at the receiver excitedly.

‘Hello?’

‘Am I speaking with the homeowner?’

The heart sinks.

‘Yeesssss.’

‘My name’s Sue and I’m calling from the NBCS . . .’

The Nautical . . . Bird . . . Canoeing . . . Society?

‘ . . . that’s the National Blind Children’s Society. And we’re looking for volunteers to collect money in their own neighbourhood, delivering envelopes and then a few days later collecting them again. Would you mind helping out?’

My mouth opened to say no thanks but then my untrustworthy subconscious lurched into action: deliver a few envelopes on my own street? Go and collect them afterwards? Why the hell not? In a moment of sudden madness I heard myself unexpectedly pronounce: ‘Yes, why not. I think. Yes, OK. But hang on, erm.’

‘Yes?’

‘All right then.’

‘Great. Just give me your address and I’ll pop it all in the post. Instructions are included. Thanks.’ And she hung up.

I was immediately flooded with wave after wave of delicious, self-righteous serotonin. Somewhat pathetically, I felt an urge to text some of my friends, informing them what a wonderful and selfless thing it was that I had just agreed to do. I imagine this was a similar sensation to having just had one’s bank details expertly stripped by Tigger-esque charity muggers down on the high street: feeling a little more buoyant in your soul but with a slight yet distinct sense of unease. Did I really want to do that? Have I been had somehow?

Sadly, this kind of reaction to having done something even vaguely altruistic is these days the rule rather than the exception. Most of us lead incredibly selfish lives – straight-ahead, blinkers-on, me, moi, ich – looking out for number one. Lifelong, short-sighted self-interest is wholly acceptable here in the early twenty-first century, indeed often positively encouraged by our inescapable double-barrelled godheads: consumerism and cynicism.

I am a consumer. I am a cynic. But I would like to be less so. I believe that being a ‘good person’, with all the responsibility and possibly hard work that might entail, is fundamental to leading a full and rewarding life. I’m not religious, so I have no spiritual dogma going down here – it’s just a yin and yang thing: cause and effect, effect and cause making a unity of opposites. You get what you give. The love you make is equal to the love you take. As you can see, I have started to regurgitate pop song lyrics, probably in a consumerist and cynical way. And all this pop-cultural meaninglessness clogs up the parts of the brain that presumably used to – back in the olden days – be filled with hale and hearty doses of fraternal philanthropy. We used to be nicer. It’s true, our grandparents insist; or at least they would if we ever listened to them. Nowadays we can’t because they’re in a care home, as this makes our lives easier. Is this the world we created?3

We children of the seventies and eighties certainly do less for other people than our parents’ generation did and, indeed, still do. Part of this has to do with the fragmentation of the community, a process hurried along by Margaret Thatcher and her infamous line: ‘There’s no such thing as society – only individuals.’ Licence to ill, in other words. More cynical is the less famous yet eviller still Thatcher quote: ‘No one would remember the Good Samaritan if he’d only had good intentions; he had money as well.’

This state-sponsored selfishness was unprecedented; it branded a deep ideological fissure into the nation’s consciousness. The great myopic gold rush had begun; a gold rush barely even mediated by over a decade of Labour government; indeed they positively encouraged it. And it’s too late to force this particular genie back into its bottle now – the genie is a hedge fund expert and has assured his dominance by wiping out magic lanterns through relentless speculation on futures trading. Sigh.

My own parents were always active in their community and elsewhere. My mother was a teacher and Red Cross volunteer. My late father would get involved in good deeds locally if there was a drink in there for him somewhere (anything pub-sponsored, for example). This giving of themselves to the community at large defined them and others like them, and continues to this day. It conferred a sense of innate Goodness; of wisdom and trustworthiness – proof that there was such a thing as society after all. In being fundamentally unfashionable myself, I feel it’s my generational responsibility to attempt to preserve this unfashionable attitude. By taking my foot off the egocentric gas, could I possibly become a bit more (although not too much, thanks) like my parents and less like . . . well, me?

As an archetypical, work-shy writer who does nothing but sit on his arse all day,4 I have quite a lot of spare time, probably more than most people. In the chaotic metaphysical and moral fallout I am experiencing post-NBCS phone call, I have come up with an idea of how to spend some of this time: a programme of self-improvement through volunteering. Because volunteer work – i.e. working for zero financial reward – is a far more structured and measurable way of leading a ‘better’ life than just giving beggars money or helping mothers with pushchairs up flights of stairs. By volunteering, you contribute to an organized infrastructure functioning exclusively in the direction of the Greater Good.

I want what follows to be an honest portrayal of these multitudinous, righteous labourings. I give myself two whole years – two years of part-time volunteer work; two years of getting properly stuck in. Not reportage: rather, earthy immersion, genuine participation and involvement; and cynicism (even pub-sponsorship) begone. Consider this a kind of learn-as-one-goes instruction manual: of fatigue-free compassion; of idealized citizenship; of inevitable humiliation, failure and deluded hubris. A step-by-step, live journal documenting the attempts of a charitable neophyte to better himself and perhaps even those around him too, through enlisted benevolence. I want to prove Margaret Thatcher5 wrong. All over again.

As a structure for this prolonged course in resensitization, I plan to utilize that traditional methodology of the vice-afflicted: the Twelve Step Programme; although having just perused the actual steps, I have decided to ignore their specific exhortations, since, for example, ‘Admitted to God, to ourselves, and to another human being the exact nature of our wrongs’ (Step 5), and ‘Sought through prayer and meditation to improve our conscious contact with God as we understood Him, praying only for knowledge of His Will for us and the power to carry that out’ (Step 11), seem to me somewhat long-winded and, to be frank, frightening. And it’s fear – this extant paralysis of idleness – that I’m so keen to move beyond.

By the end of this tough, anti-ennui regime, I hope to be in a position where I’ll be able to answer these two, crucial questions: can a thirty-something middle-class Englishman become a better person through volunteering? And might a prolonged prescription of selflessness deliver enlightenment even to a foul-mouthed commoner such as myself?6

A week after the phone call, the NBCS envelopes arrived. On the front of each was a pretty, smiling, wonky-eyed albino girl, surrounded by Harry Potter books. ‘A Brighter Outlook’ promised their slogan. I didn’t really understand, so instead I decided to count the envelopes. There were forty-two. Isn’t forty-two supposed to be the answer to the meaning of life, the universe and everything? It was a brilliant omen.

Well, I never delivered the envelopes. I couldn’t be arsed.

I’m not going to patronize you, OK?

Step One

Oxfam, Kensington High Street branch Monday morning

Number of Oxfam shops in the United Kingdom: 750Oxfam net funds, April 2006: £73.5 million

The west London borough of Kensington and Chelsea is one of the most affluent urban zones in the world and the wealthiest area, per capita, in the whole of the UK. It also holds the dubious honour of being the safest Conservative parliamentary seat in the country. Kensington High Street is these people’s ‘strip’: the cars are Porsche or Mercedes or, more likely, giant 4x4s manufactured by Porsche or Mercedes. Sunglasses are vast; children, Tarquins, out of control. The large Oxfam store is down at the north-west end of the street, almost opposite Waitrose. I have volunteered over the phone to work one shift a week; maybe even as many as two.

I arrive early, and try to get in through the front door, except it’s locked. A short and spiky elderly lady frantically waves me away, and I wave my arms around madly in response. Eventually she concedes, unlocks the door and opens it just a fraction. Her eyes are wild and her teeth are bared like a hyena.

‘What do you want?’

‘I am here to work,’ I explain through the crack. ‘For free!’

‘Well, go around the back!’

She closes the door, retreats. I go around to the back and ring the bell impatiently. Soon the back door opens and here she is again.

‘You’re too early,’ she snaps, leading me into the back of the shop where it’s dim and yellow and doesn’t smell of sweaty old clothes, but of cardboard. She disappears into a side office.

‘Hello, my name is Seb,’ I call after her. ‘I spoke to Sally, the manager, and . . .’ The job interview, a few days previously, had gone OK. I was not a thief or a rapist or a granny rapist.

The elderly lady emerges again, smoothing down mountainous collars, and mutters: ‘Gladys.’

I smile and reach to shake hands. Gladys offers an alarmed finger, which I lift up and down, twice. It’s icy cold.

‘You can hang up your coat over there. Not there. Not there. What’s the matter with you? There.’

Gladys is Thora Hird possessed by Alan Sugar. She disappears into the office again, leaving me standing alone out in the back of the shop; everywhere lie clothes, books, boxes of Fairtrade objects, bulging bin-bags. There’s a small kitchen area. It’s one of those certainties that everyone bonds over a cup of tea, especially those a little older.

‘Gladys, can I make you a cup of tea or coffee?’

‘What? You want a cup of tea?’ She emerges from the office and stares at me angrily.

‘Yes, but would you like me to make you one?’

‘I had one before I came.’

Gladys disappears again and I construct my coffee in wall-clock-ticking silence; then Sally arrives, thank God. Gladys scuttles out of the office.

‘He’s making himself a cup of tea!’ cries Gladys. ‘Already!’

Sally (managers are salaried and I think that’s for the best, otherwise all might be chaos – good-willed, sure, but chaos). She’s short-haired, wry and a bit boho. She ties on an apron.

‘Look, I even tie on an apron,’ she says.

I stand on the empty shop floor, next to some jigsaws. A customer aggressively rattles the locked front door and points hysterically at his Rolex Oyster Perpetual Yacht-Master II. He crouches down and begins to haw angrily through the letterbox.

‘Sally, there’s a scary man outside. I think he’s going to break the door down.’

‘We’re not open till ten!’ she shouts. ‘You’ll have to wait another five minutes!’

The man’s eyes bulge with rage. He rattles the door some more and then storms off down the road. Sally sighs and goes off to get her keys and then we’re open. I feel vulnerable.

Sally has decided to put me on the till with Gladys today, so that I can learn the ropes. I’m frightened. Gladys despises me, but I have no idea why this might be. OK, I have quite long hair, but I’m otherwise pretty well presented, and I’m smiling at her as much as I possibly effing can. She stares back through especially narrowed eyes; her eyebrows are painted dark, thin grey in high arches.

Soon I am trying to remove the security tag from our first sale of the day – a ladies’ small black cardigan.

‘Not like that. Not like that.’ I’m elbowed aside; and then my attempt to bag the garment is met with an unfriendly gasp; almost a growl.

‘Hey, don’t worry, that was my first one. I’ll pick it up – you’ll see!’

‘Not like that you won’t.’

All I did was put a cardie into a plastic bag. I feel a little upset.

In a little while I am introduced to Judy, a smiling and open-faced septuagenarian employee who runs the shop’s book section.

‘That woman who does the books despises me,’ says Gladys.

‘Judy? She seems so nice.’

‘Don’t be fooled. She refuses to say a single word to me, ever.’

Gladys smiles for the very first time today. It’s 11.05 a.m. Gladys’s teeth are sharp, but not quite fangs.

As the morning grinds on, Gladys regales me with customer horror stories involving theft, drunkenness, drunken theft and many different sorts of bad behaviour, including several complicated ways to get security tags off garments. The relating of these tales turns Gladys visibly apoplectic. But then I get a good one. A few years ago, when Vanessa Feltz lost some weight, she stopped by the store to donate all her old ‘fat’ clothes. Good for her. According to Gladys, Vanessa’s old clothes were then steadily bought up by a continual stream of overweight transvestites.

‘I don’t know how Ms Feltz would have felt about that. Ha!’ cackles Gladys, deliberately ignoring a man waiting to pay for a thin, striped tie. Vanessa had performed this act of magnanimity with a large film crew in tow. Soon afterwards she put the weight back on, and popped in again (this time minus the film crew) to buy all her old stuff back.

‘But the transvestites had bought all her clothes!’ crowed Gladys. ‘Ha-ha-ha-ha-ha!’

In between customers, I attempt to become Gladys’s friend. There wasn’t much else to do, really.

‘So,’ I offer, remembering the statistical breakdown Sally had given me over the telephone. ‘After women’s clothes at number one, and books at number two, what’s the third bestselling section in the shop?’

‘What are you talking about?’

While I ineptly serve another customer (they are forgiving – as you’d expect – all except the middle-aged foreign ladies), Gladys strides out back to fetch a list of each section’s turnover this financial year compared to last year’s.

‘As you can see,’ snarls Gladys, ‘you don’t know what you’re talking about. After women’s clothes comes bric-à-brac. Books are third.’

A man stands and waits patiently to buy several paperbacks, but he is made to wait a little longer while Gladys jabs an accusatory finger at the columns, all of which she had compiled and transcribed, as she does the cashing up and accounts too.

Gladys finally looks up. ‘Yes?’

‘I’d like to buy these, please.’

Gladys makes an unfriendly grunting sound.

A lady drops off a carrier bag of donated clothes.

‘Don’t put them there!’ cries Gladys. She turns to me. ‘People think they can bring all their rubbish in here instead of throwing it away. They just bring it all in and expect us to be thankful.’

I say thank you to the lady who’d dropped off the stuff.

‘Don’t say thank you like that – you don’t know what’s in there,’ hisses Gladys after she’d gone.

‘What should I say?’

‘Say, “OK then”.’

The morning brings a mad run on crockery, each piece of which must be carefully wrapped in tissue, even if it’s only priced at 9p. Gladys openly resents having to do this, and tells the customers this as she wraps. The customers then plead for her not to bother but Gladys doggedly concludes the wrapping out of malicious principle. I confess that I’m really not very good at wrapping things, or folding things – probably folding women’s clothes in particular.

‘Nor am I!’ howls Gladys.

We had inexplicably bonded over our shared fabric ineptitude. Soon we are suppressing mean giggles over my attempts to fold a lime-green ladies’ petticoat.

‘It doesn’t even matter!’ hoots Gladys.

I decide not to ask why it’s OK to screw up the folding but heinous to put it into the bag wrong.

I begin to enjoy asking people if they want a bag, in a mildly threatening and morally superior fashion. I’ve learned this off Gladys.

‘Oh, just a small one.’

Gladys and I glare slightly aghast.

‘Oh look, goodness, I’ve got one here already, never mind.’

We slide the petticoat across the countertop, folded in a kind of lopsided hexagon.

People generally behave like they’re St Mother Teresa herself when they slip their small change into the charity shaker on the till. Gladys tends to raise a plucked and painted eyebrow at them but I can’t see the problem with this myself – except when they just walk away and leave me to lean over and do it for them. I resent having to do that. This is the influence of Gladys. At 11.30 a.m. Sally brings us out coffee and biscuits on a tray.

‘I never get this,’ gasps Gladys, eyeing the tray with mock horror. ‘Never.’

I put down my coffee in the wrong place three times and then feel I’ve selected the wrong biscuit.

A plump woman comes in and buys a bar of Fairtrade chocolate and as I ring it up, stares pointedly at my T-shirt. My T-shirt says: ANIMALS: It’s Their World Too.7

‘Don’t forget that humans are animals too,’ she says.

‘I’m sorry?’

‘My daughter is at one of those schools that has animal protesters hanging around outside. You know – they shouldn’t dig up human bodies! That’s unacceptable.’

I pause. ‘Aren’t we all animals?’

‘So why doesn’t it say that on your T-shirt?’

She saunters out of the shop and then Gladys squints at my T-shirt and tuts.

‘Should I change the CD?’ I ask. The world music, which you can buy if you want, has come to an end.

‘Whatever you like. I hate it all anyway.’

At 1.15 p.m. Gladys informs me that Maureen, the lady who takes over on the till during the afternoon shift, is even worse than her.

‘Oh my God,’ I reply.

Gladys looks delighted; she even serves a customer politely. Soon Sally comes out on to the shop floor and asks whether or not I want to work the afternoon shift as well. I say no thanks, and she says OK, well, thanks then – see you on Thursday. I get my coat and leave. Gladys waves goodbye in slow motion.

‘So how is your moral compass?’ asks my wife Faye on my return home. ‘Was that time well spent? Was it “worthwhile”?’

‘I’d really rather not talk about it.’

‘I’ll bet the team spirit must be brilliant at a place like that.’

‘Yes, it is quite something.’

Oxfam, Kensington High Street branch Thursday afternoon

Average age of Oxfam volunteer: 84

Average age of Oxfam customer: 62

My second shift; afternoon shift.

I don’t think Gladys is here; I can’t see her on the till; she’s not on the shop floor; I can’t hear her Lancashire vowels bruising the air in the office either: nobody appears to be cowering or tiptoeing around, or weeping. The customers appear happy too – there’s even some banter! – indeed, the atmosphere throughout the whole store is sufficiently sunny and upbeat for me to be certain that Gladys definitely has the day off. Or else she’s downstairs in the toilet.

I am off the shop floor today – behind the scenes. I am sitting on a swivel chair out back, pricing CDs (usually £1.99), cassettes (mostly 99p), videos (often £1.99), DVDs (nobody really knows what DVDs are yet: £1.99) and lots and lots of books (99p, £1.99, £2.99, etc.). If they’re ‘something special’, I’ll check their worth online using the old wind-up Sinclair ZX Spectrum in Sally’s office. I am learning that this is a particularly dangerous job: I already have a growing pile of books and CDs by my side for my own purchase later on. Including bus fares both ways, my net earnings are already in the red, and this hoard of stuff means I’m going to be facing a potential loss of well over £20 by the end of the day (although spiritually I will have gained in the region of £23.50). From a jumbled bag of donations, I lift out a large pink Barbra Streisand box-set.

‘Barbra Streisand box-set!’ I announce to the rest of the backroom staff (two ladies steaming clothes),8 expecting them both to shout, me first! Instead they say nasty things about Barbra Streisand.

‘She can’t act,’ says one.

‘And she has a big nose,’ says the other.

I take it out to show Vanessa One (we have two Vanessas) on the till.

‘Look, Barbra Streisand box-set!’

‘Ew,’ she says. After some research, I decide to price the Barbra Streisand box-set at a competitive £9.99.

‘Only £9.99, everybody,’ I announce. ‘That’ll get snapped up. That’s a snip – one went for £11 on eBay only a week ago. I’m completely serious.’

‘You’re thinking of Cher,’ I hear at the steamer.

‘Chair?’

‘I’m OK standing.’

The steamer goes hissssss.

My pound signs look too much like treble clefs. Individualistic self-expression can be a vital, self-empowering part of the volunteering experience, it says on a piece of paper tacked to the wall in the kitchenette.

Oxfam, Kensington High Street branch Monday morning

Barbra Streisand worldwide record sales: 71 million (approx.)

Estimated dead in 1994 Rwandan genocide: 800,000–1,000,000

Incredibly, the Streisand box-set is still around.

‘Do you know what I really hate?’ muses Gladys.

Gladys has just had a row with a lady who wanted us to hold on to a few clothing items while she went to get some money, but Gladys wouldn’t do so. The lady pleaded with me, too, but I was trying, fiercely, to signal that this decision had nothing whatsoever to do with me and everything to do with Gladys instead. I had meant to get this across without Gladys seeing but I don’t think I managed it. I think the woman thought I was rather pathetic for not standing up to Gladys, but little did she know. Because of this episode, I am wary of Gladys’s new question. I am worried that the answer might be: ‘You being so pathetic and spineless.’

‘I don’t know. What do you hate?’

‘The people who came in here after the tsunami,’ says Gladys. ‘Floods9 of people coming in here and making donations – a lot of really big donations.’

‘Were they trying to put banknotes into the shaker?’ Gladys hates that.

‘No, it’s just, where were all these people at Rwanda? But for the tsunami, here they are with their money and all this . . . caring. What about Rwanda? I wanted to say.’

Customers quake slightly at the racks.

‘I can see that; the genocide, right; but people can only react to what they see in the media, and the tsunami was –’

‘But Rwanda!’

‘Were you here for Rwanda?’

‘Of course!’

‘Fewer people?’

‘Hardly anybody, especially compared to the tsunami.’ She uses the word tsunami like the Daily Mail uses the words asylum seeker.

But I’ve been brought up short by this sudden flash of context: that we’re here for a reason – a very serious reason – which is to raise money, directly, for hundreds of thousands of people in all corners of the globe as and when necessary, like a charitable Thunderbirds only without the strings. So it’s with a renewed sense of urgency that I turn to Gladys and breathlessly announce: ‘Gladys, we’re running out of £1 coins. Shall I go to the office to get some more?’

‘I told you to do that twenty minutes ago; you’re completely useless.’

I keep myself useful.

‘You know what? They think you’re a god!’ spits Gladys.

‘Who thinks I’m a god?’

‘They do. Young male volunteer? They think you’re a god! Look at all this!’ She is pointing at the small tray of biscuits that Sally’s brought out with our coffee again. We sell a lady two Catherine Cookson novels, and not only that but she wants a bag too. Then Judy walks past and the air around us becomes decidedly chilly.

‘She’d never bring me out anything. She wouldn’t even speak to me. She despises me.’

‘You told me. That’s a shame, isn’t it? What a shame.’

‘Why? She doesn’t speak to me – why is that a shame? I don’t care.’

We drink our coffee in silence. Gladys turns back to the biscuits.

‘Look at all those. They think you’re a god!’

I am embarrassed; she’s saying this really loudly.

‘Well, I don’t know about that. I don’t have a sweet tooth, so it’s not like I’m really reaping any rewards. Do you think that makes me slightly less godly?’

‘No.’

‘Do you find this boring?’ asks Gladys, during a brief lull.

‘Boring?’

‘Because I do.’

‘No, actually I find this surprisingly fulfilling, despite, um, despite the rudeness of some of the . . . customers. But then, I guess after you’ve been working here a few years –’

‘No, it’s not that. I’m just bored. I’m just like that. I’m sorry if this offends you. And I wondered if you were feeling bored because I find this particularly boring, I have to say.’

‘I’m not finding it boring yet, no – you keep me on my toes.’

‘Well, I’m sorry if I upset you earlier, but –’

‘No, no, it’s OK. You were right, I shouldn’t have left the till unattended, even for a split second.’

‘Well, I’m sorry I had to shout at you like that, but anyone can just, you know, come along and, you know . . .’

‘Really, it’s fine, I won’t do it again, ever.’

‘Well, if you need assistance, just buzz the buzzer.’

‘I was only getting a CD from over there for –’

‘You should never leave the till unattended.’

Customers stare.

‘Anyway, I’m not bored yet, no. Maybe soon, when I can relax, and –’

‘There’ll be no relaxing come Christmas. It’s hell in here at Christmas. Hell.’

‘I’ll bet even you can’t find that boring.’

‘Oh, I do. I do. I get bored very easily.’

‘Well, that’s a shame, considering.’

‘Why is it a shame? Why is it a shame if I find it boring?’

Judy walks past again and it all goes quiet. I get the impression Judy is being cool towards me because she considers me a part of the ‘Gladys axis’. I feel frustrated by this, and also trapped.

A man comes in and drops off some leaflets.

‘OK then,’ I say to him, before he scuttles out again.

‘No!’ cries Gladys. ‘Throw them away!’

I read one of the leaflets – four pages, double-sided, neatly typed in columns.

PEOPLE WHO PUT SEAT BELTS ON WHILST DRIVING ARE PROBABLY TRIGGERING RADIATION. THOSE IN THE KNOW NOTICE.

‘Oh, it’s mad leaflets,’ I say.

‘Put that in the bin!’

IT COSTS YOU NOTHING TO TAKE SOMETHING SERIOUSLY UNTIL IT MAY BE PROVEN WRONG. ONLY THE GESTAPO AND HIGHER RANKS ARE ORDERED TO DOWN PLAY ANYTHING OF IMPORTANCE THAT MAY BE OF DANGER TO YOU, BECAUSE YOU MAY SEE IT TRYING TO ATTACK.

‘Throw it away!’

‘In a minute. I’m just having a look and then I’ll throw it away.’

‘Throw it away.’

ANAGRAMS FROM PYRAMIDS: MARS DIP Y, Y DRAM SIP, ADI RM SPY, AID RM SPY, Y SPAM RID, YARDS MIPS, RAY IS D MP, MEN ARE FROM – ? WOMEN ARE FROM – ?

It quickly became boring.

‘Are you going to throw it away or not?’

‘No, it’ll give me something to read on the bus home.’

Gladys smiles a lovely amused, pitying smile and I feel all warm inside. It’s like The Waltons, or Moonlighting.

Our customers are split into seven distinct categories.

Category one: eccentric posh local (all on hearty and jovial speaking terms with the staff) – don’t buy anything except the occasional Ian Fleming paperback, or cufflinks. After they have finished rousting around the shop saying eccentric things, they suddenly remember (or are reminded) that they have to pay for the book and the cufflinks. All they have in their pockets are £50 notes and small change, and they always manage just to be able to pay with the small change, though it takes five minutes to count it all out. They count it out in a loud and mocking posh voice and it’s only afterwards you realize they’ve stolen the cufflinks.

Category two: mad local (all on reluctant speaking terms with the staff) – demand eye contact all the time. I wish they wouldn’t; their eyes are often slightly destroyed. They pick up bric-à-brac and like to ask your opinion on it. They plonk it down on the counter and say: ‘What do you think of that, eh?’ Rarely do they actually purchase it; instead they stare at the item(s) really closely until finally pronouncing, ‘I think no!’ and striding out. Everyone breathes a sigh of relief and the staff begin to recirculate that particular customer’s call-sheet of odd behaviour.

Category three: defiant young posh individualists (a lot of pouting/swishing about) – aren’t quite as sexy and/or attractive as they like to think they are. Their eyelids brood, duskily, over you while you are bagging their articles, then they toss their scarves over one shoulder and glam-flounce out. Often they’ll come back three-quarters of an hour later and go through it all again, especially if they enjoy that whole ‘big fish in a small pond’ retail thing, or if it’s raining.

Category four: the slightly ashamed not-so-posh locals (meek, ingratiating smiling) – like to justify their selections with you. ‘These pants are brand new – who’d want to throw these out! Not bad for 49p, mmm?’ Or: ‘Four nearly new hardback books for under £10? Rude not to!’ Or: ‘These plates’ll do for emergencies – especially as cheap as that!’ This category always puts its change into the charity shaker – often it doesn’t even cross the posh eccentric/mad locals’ minds to do this; besides, all their small change went towards the Ian Fleming book.

Category five: the passing poor (eyes down for a full basket) – buy the men’s clothes. (As do the occasional mid-thirties/forties upper-class homosexuals clad in tan corduroy, whiffy tweed, a sweeping beige pate and that Rupert Everett mouth thing. Saying goodbye is important to these guys – it involves four or five different and sequential eye movements.

Category six: the canny bric-à-brac/book bargain hunters – are a pain in the arse because they demand to look at all the jewellery under the sliding glass, or finger the more expensive items locked in the wall-mounted glass cabinets. Often these people arrive in pairs, and they crouch and murmur to themselves before a) walking out without saying thank you, or b) making a purchase with a smug smile, that implies this is worth much more than you’ve priced it, ha-ha-ha! We don’t care – all we want is your 49p. OK, 19p.

Category seven: the truly mad, local or not, it doesn’t matter (to be harried out using a broom). You have to keep an eye on the truly mad. You never know, they’ll probably steal things, or even stab you, according to Gladys, and she’s probably right. I’d certainly stab her.

CONSPIRACY? I WAS TOLD THERE WAS A TUNNEL BETWEEN NEW YORK AND LONDON SINCE THE 1930S. IT’S IN THE MOVIES AS A 1930S FICTION MOVIE. IF IT’S POSSIBLE TO GO THAT FAR THEN THINK ABOUT THIS. THE TWO PLACES ON THIS PLANET YOU CAN’T SEE THE THINGS IN EARTH’S ORBIT ABOVE THE PLANET ARE THE NORTH AND SOUTH POLES. YOU CAN’T SEE PAST THE HORIZON, THUS MANY THINGS MAY BE IN ORBIT ABOVE THE POLES AND COULD COME AND GO REGULARLY UNNOTICED. IF YOU PUT BOTH OF THE ABOVE TOGETHER YOU HAVE AN UNSEEN RAPID TRANSPORT SYSTEM.

I appreciate this guy’s prose is probably more entertaining than mine; you can borrow the whole leaflet if you want to. I’ll send it over via unseen rapid transport system. In fact I just have.

‘What other charity or volunteer work do you do?’ curls Gladys, right before home time.

I look at her wearily. ‘You first,’ I reply.

‘I only work here. I was asking in case you might know of something better I could do, seeing as this is so boring. I’m on the lookout for something else to do, and I wondered if you knew of anything more exciting.’

‘Really? Well, I don’t do anything else. Maybe I should.’

‘You should. A young man like you.’

‘Perhaps.’

‘Of course you should.’

‘What could I do?’

‘Anything. And then you wouldn’t need to work here.’

‘Well. Thanks.’

‘I didn’t mean it like that. You’re very . . . sensitive, aren’t you?’

‘You think?’

‘Yes, for someone who’s led such an easy life.’

‘Oh look, it’s time for me to go home.’

‘Already? You see, such an easy life.’

‘I’ll see you next week, Gladys.’

‘And off he goes.’

Customers swivel.

Oxfam, Kensington High Street branch Thursday afternoon

Today is the day I realize a number of things. The first I am quite shocked by: it is that we throw away the vast majority of our donated goods. Previously I had morally blanched at Gladys’s vicious rejection of the public’s endless thirst for unloading personal cast-offs at our front door, but as I’ve been out in the back of the shop today – seeing first-hand the abject quality of most of the black bin-liners of shit some people drop off – I’m fast swinging behind Gladys’s cold, pragmatic ‘OK then’, as the most positive reply available. Just this afternoon we have been blessed with:

Three dirty old duvets (one damp, all with weird giraffe-like stains)

One mixed selection of small, dirty, broken baskets

One lopsided old suitcase

One broken sewing machine

One pick-’n’-mix carrier bag of odd socks (old person’s)

One printer manual dated 1995

One broken tennis racket

Ditto pair of lacrosse rackets

One bin-liner of about fifteen crumpled and damp old man’s shirts (blotchy and noxious)

One 1950s typewriter (severely not working)

Etc.

A pattern is emerging. These items are faulty, broken, have outlived their usefulness; they no longer continue to function as originally conceived. In the eyes of those donating, it must feel like a shame to throw these things out when they’re almost fit to have actually been used merely one or two decades ago. Oxfam could use this though, I’m sure! Thus everything soiled, holed, botched, knackered, falling apart, limp, passé, kaput and downright useless gets chucked into the car boot and self-righteously thrown through our open back door (we need the air).

‘I’m not entirely sure we can really use this old, wet, threadbare and clearly rotting duvet. I’m terribly sorry.’

They are consistently taken aback; horrified even: ‘Oh! Well, I wish I hadn’t bothered if this is all the thanks I’m going to get!’

When you buy items at Oxfam shops, you see, you see, the whole point is that they are not broken or mouldy or with parts missing. All the good stuff (and there is a lot of good stuff amid this crap) gets siphoned off, brushed down and priced up accordingly, and then it hits the shop floor glowing – indeed it’s goddamn luminescent. You want broken baskets? Go to a jumble sale, or a car boot sale, or Help the Aged.10

Oxfam, Kensington High Street branch Monday afternoon

Psychotic episodes in UK stores, 2005/6: 24

Murders in UK stores, 2005/6: 3

The queens of the shop floor, Gladys and Maureen (the elderly lady Gladys claims is worse than her, though I find this increasingly difficult to believe, the more I see of both of these women), don’t like me stepping on their toes (literally) out on the till. I’m trespassing on their manor and I’m too bloody cheery to the volk; a more cold-hearted, pragmatic, ‘OK then’ approach is required out there at the harsh retail coalface. I’m too customer-friendly; my godly presence needs to be kept out of sight, out back where I can utilize my bulging muscular frame by lugging deliveries around. I’m not going to take this personally, if all I’m good for is unpacking the Christmas scented candles and pricing them and moving them around on a shelf. Hey, I’m just glad to be of use.11

Actually I’m beginning to see more clearly the fierce truth of our whole economic cycle – its beautiful purity; the following equation:

DONATION FILTER PRICE SHOP FLOOR SALE MONEY GOES DIRECTLY TO NEEDY HOTSPOTS.

We volunteers are merely sections in the pipe that makes this happen in the most streamlined and effective way possible.We help move things along; oil the wheels. Our shop takes up to £5,000 every day, the majority of which comes from selling things members of the public have given us for free. The whole concept is superb! My conscience is definitely beginning to feel a few fresh, green and delicious twinges of clearance torque. Somewhere in my soul, a tiny muscle flexes.

In the meantime I ask the ladies out back what are the worst things they’ve ever lifted out from donated bin-bags.

‘My worst thing was probably a bag of poo,’ says Vanessa Two.

‘A bag of poo?’

‘A carrier bag, yes, with poo in it.’

‘Dog poo or human poo or what?’

Vanessa Two looks at me. ‘You think I opened the bag?’

‘I’d rather not talk about my worst one,’ says Vanessa One. ‘It’s too embarrassing to say.’

‘I’ve also had trousers full of poo, sheets with poo on,’ continues Vanessa Two. ‘Pants full of poo, dirty socks – in fact, look, here’s a bag of dirty socks right now – a used surgical truss, trousers and pants with urine and bloodstains and a dress covered in semen stains.’

‘Is this Vanessa Feltz again?’

‘Yes, exactly.’12

‘You name it, we’ve seen it.’

‘Dead animals.’

‘Are you sure?’

‘A rat, dead in a box.’

‘Better than alive in a box.’

‘Well, I don’t know.’

We ponder what kind of rat would be the best.

Eighty-five per cent of all donations are thrown away. Oxfam spends £1 million every year disposing of it all; charity shops in the UK spend about £4 million in total getting rid of unwanted donations. In our shop, bin men come round every afternoon, and there’s always so much stuff for them to lug out that we have to tip them with Fairtrade sweeties. Sometimes they’ll have a wee rifle through and pick out a dusty old paperback.

‘It’s Jeffrey Archer!’

(I had thrown that one away accidentally on purpose.) Or they’ll root out a Spanish/Greek dictionary from 1972.

‘Can I really ’ave this?’

‘Yes, please take it.’

So we’re all happy. Except Gladys. As I’m merrily pricing up a selection of ethically sourced plastic toy safari animals – baby hippos, zebras, etc. – Gladys steams out from the office where she’s been cashing up and begins to tear a strip off me for not pressing the credit card machine button twice to get a copy of the receipt slip.

‘Gladys, could I just stop you for a second here, please? You see, I have never actually done this thing you are so angrily accusing me of.’

‘I’m not saying you have, but using you as an example of somebody who might have done it. Why do you do it? Why do you not press this button like you’re supposed to?’

Gladys in vicious mode is not nice, not even funny She reminds me of Davros except slightly more merciless.

‘I don’t know. As I have always pressed it.’

‘But as an example of those people who don’t, I’m wondering, why do you do it?’

‘I don’t know why they don’t, Gladys.’

‘I just can’t see why anyone would keep doing this. I’ve showed you, you remember, quite clearly, how to do it, but you’re not pressing it and I’m just for the love of God asking you why.’

Maybe Gladys is mad, I don’t know. What I do know, however, is that she is seriously pissing me off. I try to catch some of the other ladies’ eyes, to get some sympathy, but they’re all blindly loyal (or just blind) to Gladys and her rages. Eventually she retreats back into the office and silence descends upon our workspace once more. I am upset again. Even with just thirty seconds’ exposure, Gladys has ruined my afternoon. A glistening BMW pulls up outside the back door and an Arabian gentleman calls through his wound-down window that he has some gifts for us. I go to the door; he pings his boot open.

‘There,’ he says through the window.

I look at him. He looks at me. I look into his boot. There are some bin-bags.

‘Shall I get all these out of your boot then?’ I ask, with as much withering sarcasm as I can muster, which isn’t much, because I’m crap like that unfortunately.

‘Yes, please, right away.’

‘All right then. I will.’

He sits there watching me unload his three black bin-liners and then drives off. Vanessas One and Two then throw everything in his three black bin-liners away. This is all so noble, don’t you think?

The Thursday Club, Botley, Hampshire Thursday

Botley telephone code: 01489

Botley motto: ‘Keep Your Verges Well-Trimmed’

When I informed my mother that I was working part-time at Oxfam in a belated effort to try to improve myself, she was pleased. But not that pleased.

‘You should go and help Bob and Rosemary with their old ladies down in Botley at their Thursday Club.’

Bob and Rosemary are old family friends, although the thought of contacting them outside the usual context of Christmas alarmed me.

‘What do they do with them?’

‘They bus them to the town hall and then supply them with tea and biscuits and entertainment. Indeed, I have entertained them myself, with poetry and singing. Twice.’

‘I could help out with that whole thing, sure. When do they do all this?’

‘The Thursday Club? It tends to be on Thursdays. And yes, you should. You could help with the bus, but you could entertain them too – you could play the guitar and sing, for example.’

Everybody has all these suggestions. But anyway, I did call Bob and Rosemary; it sounded like it might be fun, plus it ought to provide me with some direct action, real-people, coalface feel-good experience. Also it would make a pleasant change to hang out with some nice old people for once. Rosemary said sure, it would be a pleasure to have me down helping for the day, and that she looked forward to seeing me next Thursday lunchtime. My mother subsequently informed me that Rosemary had told her she’d been ‘alarmed’ by my telephone call. Which is fair enough if you’ve ever heard me play the guitar. Not that I was planning to go anywhere near a guitar. Anyway, where the hell are we?

Bob and Rosemary live in a winningly higgledy-piggledy house in the village of Boorley Green, a mile or two outside the small town of Botley, which is a mile or two outside the city of Southampton in Hampshire. All their old cars sit forlornly in their higgledy-piggledy garden alongside a forlorn boat sitting underneath a tarpaulin.

‘Does the boat work?’ I ask Bob, who is dry as a bone.

‘Ah.’

‘Does the boat float?’

My spontaneous witticism is not acknowledged; instead Bob goes inside.

While they prepare themselves for today’s jaunt, I sit on their higgledy-piggledy sofa and listen to Rosemary telling me why volunteering in the Botley region is approaching crisis point.

‘The elderly and retired, who used to be the staple of volunteer work, nowadays choose to jet off and spend their retirements enjoying themselves around the world. It’s understandable, of course, that they want to enjoy themselves, but this has depleted our ranks quite considerably.’

‘Young people aren’t interested?’

‘Young people have never been interested, but then any who might be are discouraged by the precautionary red tape that the government requires in order to volunteer nowadays. It used to be OK just to turn up and get on with it, but now you’ve got to check everybody out on the police register and fill in lots of stupid forms. All the paperwork – the formality13 – puts people off coming forward. And we need these people in order to be able to carry on.’

Soon Rosemary heads off to Botley town hall in her car while Bob and I clamber into the cab of the yellow community minibus. There are fifteen-odd seats in the back. Bob drives around to our first elderly pick-up in first gear – if we come to a main road then he might risk second gear, but for the most part it’s first only – so we lurch and leapfrog through cool, grey, autumnal Botley cul-de-sacs, halting in front of the occasional net-curtained bungalow whose nets twitch briefly before a cheery pensioner emerges, venturing towards the minibus wrapped in winter coat and scarf. I offer my arm and help them up and inside.

‘A young man!’

‘Hello, I’m Seb and I’m helping out today.’

‘Always nice to see a lovely14 young15 man!’

Then there’s whispering in the back which I can’t make out.

As we collect more ladies (the Thursday Club is exclusively for the benefit of the fairer sex), the atmosphere in the bus steadily improves until by our twelfth or so collection, it’s positively rowdy back there. It’s Olive’s birthday today, but Bob’s valiant attempt to lead a chorus of ‘Happy Birthday’ at the next stop splutters out after just a few lines. Bob tells me they’re saving their energy for later, but personally I think they were a little embarrassed being forced into a cheesy ad hoc celebration like that; these ladies remind me of cats: they instinctively do the opposite of what you want or tell them to do out of some sort of subliminal rebellious principle. They’re certainly not decrepit or senile – these honeys are hot to trot and cool as you like. Every time I make eye contact with any of them, they wink. A proper, saucy wink. I don’t know whether this is instinctive or complicit.