Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Swift Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

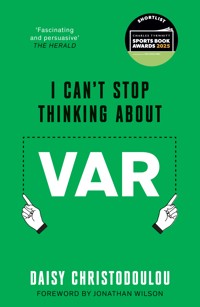

SHORTLISTED IN THE CHARLES TYRWHITT SPORTS BOOK AWARDS 2025 LONGLISTED FOR THE 2025 WILLIAM HILL SPORTS BOOK OF THE YEAR Is it football any more? 'Fascinating and persuasive' The Herald 'Everyone involved in the VAR controversy should read this short, beautifully-written book and think again' Sir Michael Barber In 2019, the English Premier League introduced the Video Assistant Referee (VAR), a way of using technology to review and correct the on-field referee's decisions. It's been a disaster: players hate it, managers hate it, pundits line up to pour scorn on its decisions, and fans have coined the chant 'it's not football any more' to describe its effect on the game. Almost every other sport in the world has managed to integrate technology into its decision-making process. Why is football failing so badly? Is it a special case, or have the game's authorities got something wrong? And what does the controversy about VAR tell us about the nature of authority, rationality and technology in the 21st century?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 206

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For Elizabeth Hanney

There rolls the deep where grew the tree.

O earth, what changes hast thou seen!

There where the long street roars, hath been

The stillness of the central sea.

The hills are shadows, and they flow

From form to form, and nothing stands;

They melt like mist, the solid lands,

Like clouds they shape themselves and go.

But in my spirit will I dwell,

And dream my dream, and hold it true;

For tho’ my lips may breathe adieu,

I cannot think the thing farewell.

‘In Memoriam’Alfred Tennyson

Contents

Foreword by Jonathan WilsonIntroduction Part 1: Problems 1. Handball 2. Fouls 3. Line Calls 4. The Flow of the Game 5. Human Error Part 2: Solutions 6. Continuums and Categories 7. Measuring Fouls 8. Margins of Error 9. Automation 10. Autonomy 11. Transparency Part 3: Diversions 12. Progress 13. Authority 14. Idolatry Notes AcknowledgementsForeword

Jonathan Wilson

It was in Düsseldorf that the revelation struck. I’d been invited over by the local tourist board before the Euros and been taken to Fortuna against Greuther Fürth in 2.Bundesliga. In the second half, a Fortuna player seemed to have scored a brilliant overhead kick, the sort of goal that gets you to your feet even if you have no investment in the game. But it became apparent something was wrong. The players had not gone back to their own halves. They were hanging around, waiting. Everybody waited. For four or five minutes nothing happened. Then the referee thrust his arm into the air: no goal.

To be honest, I hadn’t even realised they had VAR in 2.Bundesliga. Which was when it hit me: I go to probably around 80 matches a season for work and pleasure, but this was the first time I’d ever been to a game in which VAR was in operation but I wasn’t in the press box. I had no screen look at. There were no replays visible to me. I looked on social media, but nobody on my feed was talking about Fortuna Düsseldorf vs Greuther Fürth, let alone uploading replays. For those four or five minutes, I had no idea what was going on. I chatted with the people around me. What were they checking? There was nothing obvious. The player who had executed the overhead was definitely onside. There had been no apparent contact between players, no handball. Eventually, trying to play back the action in our minds, we deduced the issue must have come when the ball was initially played wide, 15 or 20 seconds before the goal. Had there been an offside then?

I still don’t know for sure, but that’s a best guess. Offside was given, although the free kick was taken from a more central position. And that was when it really dawned on me: VAR, in its current form, is terrible, at least in terms of the in-stadium experience.

A few months earlier, I’d been in Sweden, the only one of Europe’s 30 highest-ranked leagues not to have adopted VAR. As the financial structures of modern football have increasingly shut their teams off from the sort of European achievement enjoyed by Malmö and IFK Gothenburg in the seventies and eighties, Swedish football has begun to market itself as a fans’ paradise, a place that retains a traditional football feel. That itself is a contested notion, given the excesses and self-importance of many ultra groups, but one area of unanimity among fans is their opposition to VAR.

My attitude at the time hadn’t really changed from a decade earlier, when I’d thought VAR desirable in principle but was unconvinced about how it could be implemented. What talking to Swedish fans made me realise was the extent to which VAR is a phenomenon that exists because of television fans who, seeing replays of errors within a few seconds, are much less tolerant of them than those in the stadium who might not learn a decision is wrong until several hours later. (As phones, networks and stadium WiFi improve, those two groups may converge.)

That slightly hardened me against VAR, if only for reasons of nostalgia. It’s impossible not to be aware as I approach fifty of how the experience of the game has changed since I was a child and, sport being an inherently conservative activity, resisting that. Just as I essentially think that kits should look like they did in the eighties, so I have a sense that kids should get into football in the way I did: by paying their £2.50 every week to stand on a terrace. Whatever was miserable about that experience – and much was, from the rain to the undertone of danger to the abysmal football being played – it did at least foster a sense of community, an indelible identification with place. Most of my relationship with home is mediated through football. Although far more fans these days watch on television than go to the ground, I still instinctively privilege match-going fans.

But it was only in Düsseldorf I realised just how dreadful the in-stadium experience of VAR is if you’re not sitting in a press-box with a monitor in the desk next to you. VAR has since come to seem a symbol of the general contempt with which football’s authorities treat match-going fans.

Does that mean I’m opposed to it? No. Not in principle. The problem is that it was imposed as a fait accompli for the 2018 World Cup with next to no consultation either as to whether it was desirable, or as to what form it should take. That it might expose grey areas in the existing laws seems to have occurred to no one.

Nobody had done what this book does, which is to lay out the various issues and compromises involved with VAR, using expertise from other fields, asking what exactly we want the game to look like and proposing a framework of how we might get to a workable model.

Over the past six years, I’ve read and discussed VAR so much the tendency is for my eyes to glaze over. Daisy’s achievement has been to open my eyes again and make me think, ‘Yes, this is the debate we should have been having all along.’

Introduction

France vs Republic of Ireland, 18 November 2009

It’s extra time in the second leg of a World Cup qualifier play-off. France and Ireland are tied at 1–1 over the two legs of the match, and there are just 17 minutes to go before the game goes to penalties. If Ireland win, it will mean they qualify for their first World Cup in 16 years. Florent Malouda sends a long free kick into the Irish penalty area. It looks as if he has over-hit it and that the ball will go out for a goal kick. But somehow, the talismanic French forward Thierry Henry keeps the ball in and then crosses it for his teammate William Gallas to score.

The French players run away celebrating, but the Irish players are just as animated. They surround the referee, tapping their hands, signalling that Henry used his hand to control the ball and stop it going out. A few seconds later, fans at home can see exactly what they mean. The slow-motion replay shows that Henry was only able to keep the ball in by handling it – not just once, but twice. The referee, Martin Hansson, doesn’t seem to have had a great view of what has happened. He was standing at the other edge of the penalty area, and there are a few players in between him and Henry who probably blocked his line of sight.

The Irish players protest and protest, but the referee has awarded the goal and there is nothing that can be done to change the decision.

This incident has far-reaching implications. Many other sports have introduced some form of decision review system to help officials make difficult judgement calls. Football is an outlier. FIFA, the game’s governing body, has resisted the introduction of technology, saying it would interrupt the natural flow of the game.

But it is a stance that is increasingly difficult to justify. Of course, referees have always made mistakes – Henry’s handball draws instant comparisons with Diego Maradona’s infamous ‘Hand of God’ goal from the 1986 World Cup – but in 2009, technology is reshaping the way the whole world works. Fans at home and in the ground can instantly see replays and commentary on their TVs and smartphones. Other sports are embracing the opportunities of technology. Younger fans simply don’t understand why you can’t easily overrule such an obvious howler. It feels like a watershed moment, one where the increasing pressure for change finally makes a hidebound institution crack. Some form of technological decision review system feels inevitable.

Germany vs Denmark, 29 June 2024

It’s just after half-time in the Euro 2024 match between the hosts, Germany, and Denmark. David Raum chases down a loose ball on the left wing and attempts to cross into the Danish box, but it’s blocked by Joachim Andersen and the ball goes out for a corner.

Michael Oliver is the on-field referee and, unlike Martin Hansson in 2009, he has the support of technology. There is another official, a video assistant referee (VAR), who is watching the match on a screen and can tell the on-field referee if there are any decisions he should review. In this case, the VAR tells Oliver to look again at Andersen’s block. Oliver reviews the incident on a screen at the side of the pitch and decides that Andersen has blocked the ball with his hand. It’s therefore a penalty. He’s helped in his decision by a ‘snickometer’, a sensor placed in the ball which shows that Andersen did indeed handle it.

But while the ball may have touched Andersen’s hand, most pundits and ex-players are left frustrated by the decision. Andersen is running at speed, trying to get back and defend. He is incredibly close to the ball when Raum hits it. He does turn his body, attempting to block the cross with his back, but the ball is hit at pace and it catches him on the arm. It’s hard to see how he could have avoided it. He has not gained much advantage from the action, and it feels incredibly harsh to penalise his team with a penalty. Denmark go on to lose the game 2–0 and are knocked out of the tournament.

By now we are so used to inexplicable VAR decisions that ITV have employed a specialist referee and lawyer, Christina Unkel, to attempt to make sense of them. She does a good job of explaining why the laws mean we have ended up in this place. But she does not convince anyone that the outcome makes any kind of sense. The relevant section of the law is as follows:

It is an offence if a player touches the ball with their hand/arm when it has made their body unnaturally bigger. A player is considered to have made their body unnaturally bigger when the position of their hand/arm is not a consequence of, or justifiable by, the player’s body movement for that specific situation. By having their hand/arm in such a position, the player takes a risk of their hand/arm being hit by the ball and being penalised.

The judgement is that Andersen has made his body unnaturally bigger in a way that is not justifiable by his movement. But he is running. People do move their arms away from their bodies when they are running. It would be more unnatural if they didn’t.

While the pundits are frustrated, they are not surprised. This is not the first time that the VAR system has led to a result that seems completely opposed to any notion of common sense. The commentator, Clive Tyldesley, concludes by saying, ‘The handball rule should be written for the whole game, not for VAR. Don’t force a schoolteacher to tell a nine-year-old boy or girl that their body silhouette was unnatural. There’s no snickometer on the playing field. It’s orange-juice time. Rip it up and start again.’

VAR was meant to solve glaring errors like the Henry handball, but it has ended up being used to create handball offences that previously may never even have been spotted, let alone penalised. Many fans, players and managers are sick to death of it. It’s been used in the Premier League since 2019, but far from overcoming its teething problems, its flaws seem only to have increased over time. Wolverhampton Wanderers were so frustrated with VAR’s performance in the 2023–24 season that they asked for a vote on getting rid of it. In 2024, Sweden became the only one of the top 30 leagues in Europe to reject its use. Fans in Norway dislike the system so much that they have started throwing Danish pastries and fishcakes onto the pitch in protest.

Similarly, by the summer of 2024, the wider debate about technology and authority is much darker than it was in 2009. In 2009, the iPhone was a glorious new piece of technology, and a fresh-faced Mark Zuckerberg was promising that Facebook would bring the world closer together. Smartphones and social media were going to deliver a new era of connection, prosperity and entertainment. By 2024, however, the mood is different. Technology companies are being blamed for disinformation, election interference, low-quality jobs and mental-health crises. The big new debate in technology isn’t about which new social media start-up is the coolest, but rather whether artificial intelligence is going to destroy us or if it’s just a giant con. Apocalypse or trillion-dollar grift: take your pick.

It’s hard not to see the persistent and seemingly unfixable woes of VAR as a symbol for wider technological hubris and overreach. In 2009, using technology in sport felt inevitable in a good way, like it was on the right side of history. In 2024, it still feels inevitable, but more in the way that the eventual collapse of the universe into a black hole is inevitable.

What on earth went wrong? How has something that should have been such a simple improvement ended up causing so much controversy and unhappiness? And is there any way we can fix it?

Part 1

Problems

1

Handball

‘If the rule you followed brought you to this, of what use was the rule?’

Cormac McCarthy, No Country for Old Men

The Spirit of the Law Leads to Inconsistency

It is obvious why the handball law exists. If you don’t have a law about handball, you don’t have football. When football players break this law, as William Webb-Ellis is alleged to have done in 1823, they aren’t playing football any more.

Before VAR, the handball law was quite simple. It was just 20 words long, as follows:

Handling the ball involves a deliberate act of a player making contact with the ball with the hand or arm.

There were three bullet points clarifying what ‘deliberate’ meant, but these were advisory. It was a law that gave referees a lot of discretion.

Discretionary laws rely on a shared understanding of the spirit of the law. They work on the basis that everyone – players, referees, fans – has a common-sense understanding of what the law should be, and they give the referee latitude to use their discretion to make decisions about what does and does not infringe it.

In some ways, this approach can work well, but its major problem is inconsistency. Different referees will interpret laws in different ways, and even the same referee might judge two quite similar incidents differently. When that happens in the same match, it’s hugely controversial.

Inconsistency is a threat to the integrity of any authority. If we are going to be penalised for not following laws, then we want to know exactly what the laws are and what we have to do to avoid being penalised. Players and managers develop tactics and strategies designed to work within the laws. If they can’t be certain about how the laws will be interpreted, it makes that job much harder.

Inconsistency is also a problem because it frequently leads to accusations of bias: how come this team gets marginal handball calls in its favour, and that team doesn’t?

When you see how attempts to enforce consistency go wrong, it is easy to criticise them as pedantic, bureaucratic nonsense. But the impulse to improve consistency is not nonsense; it is something that most fans care deeply about, and it goes to the heart of issues about fairness.

The other problem with the old handball law was the one bit of specific guidance it did give: that a handball had to be ‘deliberate’ to be an offence. Often it was hard to know when a handball was deliberate, and players could still get big advantages from accidental handballs. One famous example was Laurent Koscielny’s last-minute winner for Arsenal against Burnley in 2016. Koscielny miskicked the ball, which flew up, hit him on the hand and went into the goal. It was definitely accidental, as it all happened so quickly there was no time for any deliberation. But something about the decision felt wrong, as it would never have been a goal if the ball hadn’t hit his hand. In the 2018–19 season, there were other high-profile accidental handball goals from Willy Boly, Alexandre Lacazette and Sergio Agüero.

Incidents like this have been happening since football began. But improved TV coverage brings more scrutiny by pundits and fans. A video review system increases this scrutiny, and it’s hard to sustain a discretionary law when incidents can be pored over and replayed in such detail.

At the same time as video review systems were being trialled, changes to the handball law were being discussed too. In 2019–20, a new handball law and new video assistant referee system were introduced into the Premier League at the same time. The VAR system had been used in other competitions, including the World Cup and Champions League, in previous seasons, but the handball law was new for everyone and had been developed by the International Football Association Board (IFAB), who set the laws of football.

This is what the law became in 2019–20:

It is an offence if a player:

• deliberately touches the ball with their hand/arm, including moving the hand/arm towards the ball

• gains possession/control of the ball after it has touched their hand/arm and then:

– scores in the opponents’ goal

– creates a goal-scoring opportunity

• scores in the opponents’ goal directly from their hand/arm, even if accidental, including by the goalkeeper

It is usually an offence if a player:

• touches the ball with their hand/arm when:

– the hand/arm has made their body unnaturally bigger

– the hand/arm is above/beyond their shoulder level (unless the player deliberately plays the ball which then touches their hand/arm)

The above offences apply even if the ball touches a player’s hand/arm directly from the head or body (including the foot) of another player who is close.

Except for the above offences, it is not usually an offence if the ball touches a player’s hand/arm:

• directly from the player’s own head or body (including the foot)

• directly from the head or body (including the foot) of another player who is close

• if the hand/arm is close to the body and does not make the body unnaturally bigger

• when a player falls and the hand/arm is between the body and the ground to support the body, but not extended laterally or vertically away from the body

This law is 11 times longer than the previous one and does not rely on an understanding of the ‘spirit of the law’. It’s the opposite: a ‘letter of the law’ approach that reduces discretion and judgement and attempts to precisely define all the possible ways a ball can strike a hand.

It was a bit of a coincidence that the new handball law and VAR were introduced into the Premier League in the same season. But in another way, the two are closely linked. The changes to the handball law would have been impossible to implement without some form of slow-motion replay and scrutiny. Likewise, once you introduce a video review system, it’s much harder to maintain a discretionary law. Referees, players and fans are going to want more guidance.

The Letter of the Law Leads to Absurdities

But if the spirit of the law leads to inconsistencies, the letter of the law leads to absurdities.

In the first week of the 2019–20 season, VAR and the new handball law were immediately in the spotlight. Leander Dendoncker thought he had scored for Wolves against Leicester, but the goal was overturned by the video assistant referee, who spotted a handball by Willy Boly in the build-up.

A week later, something similar happened. Gabriel Jesus thought he had scored a last-minute winner for Manchester City against Spurs. But the goal was reviewed, and it turned out that his teammate Aymeric Laporte had touched the ball with his hand in the build-up.

In both cases, the handballs were accidental. Under the previous law, therefore, they would not have been penalised. But under the new one, accidental handballs that lead to goals are an infringement. In a pre-VAR world, it would have been highly unlikely that either handball was noticed in real time. You need the slow-motion scrutiny of VAR to spot the offence. These were textbook examples of the new law and the new video system teaming up; this was literally what they were designed to do.

After the Boly handball, former referee Dermot Gallagher praised the system and said it was working as intended:

It [the Boly handball] was only controversial as people were not aware the law had changed. It was correct – the referee has no choice. The law changed in the summer and if a player is struck on the arm or hand by the ball and it goes into the net then the goal will be disallowed. It is a mandatory thing, there’s no grey area.1

But while Gallagher was adamant the new system was working well, many other people were not so sure. It felt incredibly harsh to rule out goals as a result of the ball accidentally brushing players on the hand. In reference to the Laporte incident, the Match of the Day pundit Danny Murphy said, ‘The new handball rule is ridiculous. That should never on any playing field anywhere in the world be disallowed.’ He also emphasised the link between the new law and VAR: ‘It wouldn’t even be seen if we didn’t have VAR.’ His fellow pundit Alan Shearer said, ‘There is not one player on that pitch who thought that was a handball or who complained.’2

But it was not an isolated incident. Similar examples piled up as the season went on. In January 2020, West Ham had a last-minute equaliser against Sheffield United ruled out for a handball. The goal was scored by Robert Snodgrass, but Declan Rice was penalised for an accidental handball in the build-up to the goal. Again, this infringement would not have been spotted without VAR, and even if it had been, under the previous law it would have been deemed accidental. In this case, it felt particularly harsh because quite a few seconds elapsed between the handball and the goal. After the ball brushed his hand, Rice shook off one opponent, dribbled past two others and passed to Snodgrass, who scored. We all thought that the point of the law change was to prevent incidents where the ball deflects off someone’s hand into the goal. Instead, it was picking up incredibly marginal accidental handballs that occurred at the very start of a chain of events that led to a goal.

After this match, the former referee Chris Foy wrote an article for the Premier League website, saying that overturning the goal ‘was the correct decision and good use of VAR’. But he also said that he understood Rice’s frustration and that the decision was right according ‘to the letter of the law’.3 His phrasing made it clear that there was something about the decision that was not right according to the spirit of the law.