13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

Between 1967 and 1997 Keith Spragg progressed from the greenest new co-pilot on a piston-engined Vickers Viking to a fully qualified jet captain. He then went on to become an experienced pilot trainer and examiner, ultimately flying ten different types with nine different airlines. The story of that journey, told in I Have Control, is a personal one but is also part of the wider story of airline development. Keith witnessed many changes and it was not only the aircraft that changed; the training, attitudes and culture of airline pilots themselves were transformed over that period. Under the day-to-day demands of disrupted rosters and unsociable hours, the moments of humour and the need to squeeze as much fun as possible out of every day, the significance of these changes was not always obvious. Now, with time to reflect, the small boy's fascination with flight lives on. While the job changed, the rewards, the comradeship and the sense of privilege continued. But now Keith asks tough questions about the application of technology. Is the modern flight deck fit for purpose? Have we sacrificed skill on the altar of technology? How should the industry respond to the prospect of artificial intelligence and pilotless airliners? His account will be of interest to all aviation enthusiasts and is illustrated with 8 colour photographs in a four-page colour section.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

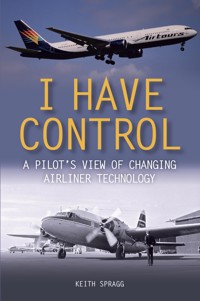

I HAVECONTROL

A PILOT’S VIEW OF CHANGINGAIRLINER TECHNOLOGY

KEITH SPRAGG

Airlife

First published in 2018 by

Airlife Publishing, an imprint of

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2018

© Keith Spragg 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced ortransmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical,including photocopy, recording, or any information storage andretrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 398 1

Front cover images:

ABOVE: Three hundred and forty Souls On Board. The largest aircraftKeith flew, the Boeing 767-300ER with a maximum weight of over185 metric tonnes and a range in excess of 6,000 miles.

DEAN MORLEY VIA FOTER.COM

BELOW: Keith’s first airliner and the end of an era. A Vickers VC1Viking of Autair International Airways about to depart from Lutonairport in the late 1960s. KURT LANG

Contents

Introduction

Chapter 1As It Was

Chapter 2To Berlin

Chapter 3The Viking

Chapter 4Turboprop Schedules

Chapter 5The Jet

Chapter 6Caribbean Contrasts

Chapter 7A Boeing in Borneo

Chapter 8The Mighty 707

Chapter 9Trainer

Chapter 10Flight Management Computers

Chapter 11Wide-Body

Chapter 12Starting Again

Chapter 13And Again

Chapter 14Beauty and Two Boeings

Chapter 15Fly-By-Wire

Chapter 16Culture Shock

Chapter 17Concerned Observer

Chapter 18Post-Flight

References

Glossary

Index

Plate Section

Introduction

There is something special about flying. In previous times, people turned to the sea if they yearned for adventure and those who found it sometimes wrote accounts of their experiences that inspired countless others to follow in their wake. As a boy I read the books of Arthur Ransome and dreamt of going to sea myself, but this idea was gradually overpowered by the flying stories I read later. The early aviation pioneers, the record breakers in the 1930s and the British test pilots who, in the 1950s, were pushing the boundaries of speed, altitude and distance, described something that was, to me, even more exciting.

By my eleventh birthday it was decided: I was going to be a pilot. Of course, at that age one does not consider the difficulties that might be encountered when one attempts to follow one’s dream. I belonged to a normal, working-class family. My father was a printer, a seven-year apprenticeship, hot-metal man, who wanted a safe, reliable trade for his two sons. While we enjoyed a good standard of living, it was hard-earned and there was little money to spare. My mother was widely read and had more sympathy for our aspirations, but we were really not the sort of people who flew. Worse, I was not academically gifted. I hated school and it was not until I was fourteen that I even began to understand the connection between examinations and employment.

The conventional answer to my problem was to join the Royal Air Force, a route many young men like me had taken with success. For a long time it seemed that I had no alternative. I joined my local Air Training Corps squadron, made some good friends, learnt a lot and enjoyed a variety of sports, but my heart was not in the military. The RAF wanted officers to lead and to fight; flying was incidental to the task. I just wanted to fly and the conviction was growing in me that the life of an airline pilot would be the ultimate expression of my desire.

Turning my back on the RAF delivered a strong dose of reality. There followed a frustrating period where I worked at various jobs while searching all the time for some way into civilian flying. A Commercial Pilot’s Licence is the basic requirement for being paid to fly and at the time, in addition to passing the exams and tests, the experience requirement was 150 flying hours. It seemed not an insurmountable total, given the availability and relatively low cost of ex-wartime Austers and Tiger Moths at local flying clubs. But I wanted the best possible training, so I sold my car, scraped together my savings and embarked on a course of training for my Private Pilot’s Licence with the Oxford Air Training School’s centre at Elmdon Airport, Birmingham.

Just as I received my Private Pilot’s Licence and started to build my hours, a Government Committee on Pilot Training changed the rules. The experience requirement for a Commercial Licence was raised to 700 hours. It looked hopeless, but my determination had been noticed and some people had faith in me. Principal among these was Gordon ‘Ginger’ Bedggood, Chief Flying Instructor at Birmingham who offered me a contract to work as a general dogsbody at his new school with minimal payment, but with training to become an assistant flying instructor. At that time, a flying instructor did not need a Commercial Pilot’s Licence, provided that he and his students belonged to a registered club. Four years later, in 1967 I had the licences I needed to fly for an airline.

I joined Autair International Airways as a co-pilot on the Viking Freighter at its base in Berlin, later moving to Luton on the Handley Page Dart-Herald and then the BAC1-11. I got my command on the BAC1-11 in April 1971. Autair became Court Line Aviation and expanded rapidly, until it went bust in 1974. After a brief spell of unemployment, I joined Monarch Airlines, again on the BAC1-11, then, in 1975, Royal Brunei Airlines, which was just starting a new operation in Brunei with Boeing 737-200 aircraft.

Four years later, I joined Cathay Pacific Airlines as a first officer on the Boeing 707 aircraft, but returned to the UK to join the new Orion Airways, again initially on the Boeing 737-200. I qualified as an instructor and examiner with Orion (IRE/TRE) on the Boeing 737-200, 737-300 and Airbus A300B4. When Orion was taken over by Britannia, I joined TEA – Trans European Airways – as a trainer on the Boeing 737 until that company too folded.

My last employment was with Airtours International (since renamed as MyTravel and now merged with Thomas Cook), first as a captain on the MD83, then as a trainer on the Boeing 767, Boeing 757 and the Airbus A320/321, serving briefly as Long-Haul Fleet Manager. I retired in 2001, having accumulated a total of 17,200 flying hours, including over 12,000 hours in command on jet transport aircraft and a further 2,500 hours in flight simulators.

This book contains my reflections on those thirty years. Many airline pilots stay with one airline throughout their careers. They are discouraged from changing employers by the seniority system that ensures, should they decide to switch, they will have to start again as the most junior co-pilot in the fleet. It is only when new airlines are formed, or during periods of unusually rapid expansion, that direct-entry captains are accepted. Had Court Line survived, I would probably have stayed with them until I retired. But they went bust during the fuel crisis of 1974 and I was launched onto a more varied path.

It was all great fun. Some of the changes that followed were enforced by financial failures or takeovers, some through my own efforts, but throughout I was extraordinarily fortunate. I remain forever grateful to my family, friends and colleagues who helped me along the way. The flying always lived up to its promise and I never once regretted the course I had taken. Even when I eventually encountered medical problems and lost my licence, I was conscious more of how lucky I had been than of any disappointment at no longer being able to fly.

It is natural to want to share some of that experience with others, but I had read enough self-indulgent autobiographies and didn’t want to inflict another one of those on anyone who might be interested in what I had to say. So I thought long and hard to determine what was unique about my experience. I tried to see my career in context, to understand what was happening to society during that period and what I had learnt that would be relevant to other people’s lives.

It was not difficult to see that changing technology has had, and continues to have, great influence on people’s lives. In many ways, aviation is at the forefront of the introduction of technology and I realized I had witnessed a broad spectrum of change through the aeroplane types I had flown. Just as my father’s trade was to be superseded by computer layout and printing techniques, and the pens and pencils of my brother’s days as an engineering draughtsman were to be overtaken by computer-aided design, so the basic flying and airmanship skills I had learnt during my training were being threatened by sophisticated digital autopilots and Flight Management Systems (FMS). The days of ‘a job for life’ are long gone and the idea of ‘taking up a trade’ is antiquated. What I came to understand while writing this book is that opposition to technological progress is futile, but that is certainly no cause for despair. Technology can make life safer, more productive and more rewarding. It can relieve us of boring, repetitive jobs and allow more of us to enjoy creative and interesting work. The Luddites are wrong. Young men and women will encounter great changes over the course of their adult lives, but they must still follow their dreams. Their focus may initially be narrow, but they must learn to broaden their interests and to explore new opportunities so that they can be flexible in the knowledge, skills and attitudes they acquire. As a society, we should pay more attention to ensuring that technology is developed in accordance with human needs and aspirations, helping to satisfy them, and to make full use of them, not to banish them. With the imminent introduction of computers making use of Artificial Intelligence, these two requirements – keeping an open mind and developing technology that is subservient to human needs – are more important than ever.

CHAPTER 1

As It Was

The light is fading as we drone over featureless stratus cloud towards Wolfsburg at the entrance of the Centre Corridor that leads to Berlin. My captain, known to everyone as Speedy because his reactions are so slow, is tapping his foot in time to the brass band music that I know is playing through his headphones. His bushy eyebrows move randomly. The smoke from his cigarette curls lazily up from his hand on the control wheel before it is drawn away through the open side window.

‘Tempelhof is below limits, Speedy,’ I say. He doesn’t respond, so I wave the weather reports under his nose. He takes them, scanning them without a word.

God, he annoys me! I’ve got nearly 2,000 hours and reckon I know a bit about flying, but I’m completely ignored. Under the regulations, we are forbidden to enter the corridor unless the cloud base at our destination is at least 300ft and the visibility is more than 600m.

In a few minutes it will be too late; we can’t turn round in the corridor.

‘Hanover?’ I prompt. The ash on his cigarette grows another quarter of an inch. I wait. The foot keeps tapping and, bizarrely, I seem to detect Procol Harum’s ‘Whiter Shade of Pale’ running through the harmonics from the engines and propellers. Why can’t the Old B… make a decision?

Eventually, he takes a long drag on his cigarette, holds it nearer the window so that the ash is whisked cleanly away, and speaks. ‘We’ll just have a look,’ he says.

Have a look? What’s he talking about? We’re not allowed to ‘have a look’. But I know he won’t listen to anything I say, so I get out the charts for an Instrument Landing System (ILS) approach to runway 27 Left at Tempelhof. I study the go-around procedure and the route we will have to take from there to Hanover. We have enough fuel, but not much extra.

I change frequency to the American controller in Berlin, who identifies us on radar and, when we get nearer to the airfield, starts to give us vectors towards final approach. We descend into cloud and it is immediately darker. There is light turbulence. Ice starts to form on the airframe and round the engine air intakes, but this soon changes to rain, rattling like hail on our cockpit. Water flows in through the windscreen and drips onto our knees. I get an update on the weather – it’s worse, but Speedy only grunts.

‘You are cleared to descend with the glide path.’ The controller sounds bored, near the end of his shift and ready for a drink. ‘Contact Tower now gentlemen, Good day!’

The gear is down and locked, checklist completed, we’re cleared to land or go-around. Apart from the final extension of flap, which in this aircraft is never made until a landing is assured, I have nothing to do but monitor the instruments and call the heights.

‘One hundred above!’ I call at exactly 300ft above airfield level. We must have the approach lights in sight at 200ft or apply full power and climb away. It is fully dark now and still turbulent.

‘Wipers!’ I flick the rotary switch on the overhead panel and the archaic system of rods and cranks whirls into life, though the wipers make absolutely no impression on the water streaming over the screens. I can’t see a thing outside.

I am impressed, reluctantly, by the precision of Speedy’s flying. The electronic instrument landing beams are very narrow at this level and the lower speed of the aircraft demands larger control movements, but he keeps the needles exactly centred. He makes swift, nervous corrections to the control wheel. His eyebrows are thrashing about now too and his face is twitching.

‘Minimums!’ I call, moving my hand toward the throttles to make sure they go fully forward.

‘Full flap!’ Speedy shouts.

What? Full flap means we’re landing, but nothing beyond the windscreen has changed. I can’t even detect a lightening of the black void to indicate we’re over the approach lights.

‘Full flap!’ Speedy curses, so I select it, feeling the aircraft pitch down as the drag increases, open mouthed in disbelief, amazed at how Speedy keeps the needles centred, despite the change of trim. His movements are now an intense blur.

Outside, we are still in complete blackness and streaming rain. There is a swish of tyres on wet tarmac and then one dim light slides down the right-hand side of the aircraft. There’s another, and another, on the left this time, and then a string of runway lights appears to show that we are slowing in the centre of the runway.

We turn off the runway and taxi to the apron in silence. Speedy is a criminal and I’m an accessory. But I’m in awe of the most amazing piece of flying I’ve ever seen, a display of unbelievable skill.

When the doors are opened everyone is disturbingly normal. The engineers and the customs men are all as courteous and welcoming as ever. Don’t they understand that Speedy has got us here by a miracle? He’s made a completely blind landing hand-flying an ancient aeroplane with very basic instruments.

He has already packed his stuff away and got his raincoat on while I complete the paperwork. He picks up his briefcase. He never says good morning or goodbye; usually he just stalks off. He’s an ignorant, bad-tempered old tyrant. But tonight he pauses to look me in the eye. Could that be the ghost of a smile on his lips? He gives a broad wink, and then he is gone.

CHAPTER 2

To Berlin

There aren’t any characters nowadays, I thought. Not like there used to be. I was browsing through my old logbooks, thinking about the early years of my career as an airline pilot. The pages from 1967 and 1968 contained only the bare facts of each flight:

REGISTRATION:

G-AGRW

TYPE:

Vickers VC1 Viking

FROM:

Schipol

TO:

Tempelhof

DEPARTURE:

1400

ARRIVAL:

1630

TOTAL TIME:

2 hours 30 minutes

Here and there, when the captain had graciously allowed me to land the aircraft myself, he had added his signature to authenticate the claim.

When I turned a page, a photograph slipped out. It revealed a youthful version of me sitting at the controls of the piston-engined freighter. My uniform carried a single gold stripe. The windscreen was edged in wood and the profusion of large, strangely shaped levers and mysterious dials had clearly not been influenced by modern ergonomic design.

Memories surfaced quicker than I could organize them: the excitement of living in the divided city of Berlin, the hippy phenomenon and student riots, and how cold it used to be in the unheated aircraft. The flight deck had been noisy and everything vibrated, but, despite its nickname of ‘The Pig’, the Viking handled beautifully in the air. The flying control surfaces were linked directly by pushrods, cranks and cables to the control column – no power assistance – and the airflow made it come alive. Flying it had felt like stroking a wild animal.

I reached for a drink and suddenly I could smell that cockpit once again. Spilt coffee had made the controls and radio panels sticky. The odours of fuel, leather and hot electrics, mixed with the accumulated dust and grime of the cargoes we carried, came back to me. At once I was slouching again in that comfortable leather co-pilot’s seat.

An idea was forming: it seemed to me to have been an extraordinary journey from junior co-pilot on a piston-engined freighter to modern airline captain. Should I write about it? Would anybody want to read what I wrote? The lack of a literary tradition was discouraging. I knew of only two memoirs by airline pilots: A Million Miles in the Air by Captain Gordon P. Olley1 and Fate is the Hunter by E.K. Gann.2 Olley was an Imperial Airways pilot who wrote his book in 1934. He was an early pioneer who made seventeen forced landings during his first passenger service from London to Paris; his story was obviously justified by its historical significance. Gann was an accomplished professional writer whose record of his airline experiences from the 1930s, through World War II and into the 1950s has become a classic; it is regarded as compulsory reading for anyone who flies.

There was nothing that had been written later, a fact that argued for doing something about it, but alongside these two great books, any effort of my own would be modest indeed. I am just one of many people who did this job. I fought no wars, had no crashes and never got my name in the papers. I would have to concentrate simply on what life was like for an airline pilot during my years in the job. It would be nice to capture some of the magic, but that would involve describing emotions, which is the very antithesis of an airline pilot’s creed. Flying may be seen by some to be an exotic way to earn a living, but the truth is, of course, more prosaic and my erstwhile colleagues would be quick to ridicule my efforts if I tried to glamorize it. Pilots are no different to people in any other profession. The slim, grey-haired veteran who commands immense respect, looking elegant in his immaculate uniform, exists; so too does one of the best airline pilots I flew with. He was a short, overweight, unshaven scruff who carried his manuals and night-stop gear in a plastic carrier bag. All I could do would be to aim to keep it simple, to confine myself to my own personal impressions and to be honest. At the very least I might encourage some of my contemporaries, who have more interesting stories to tell, to pick up their pens or settle to their word processors.

It didn’t seem enough. I dismissed the idea several times, but further thought made me conscious of another story that ran parallel with my own. During the time I was airline flying, the aircraft changed significantly. From hastily designed post-World War II piston-engined types with low power, poor performance and very basic equipment, we progressed to high-performance, pressurized jets. Then came the sophisticated autopilots, remarkably accurate navigational aids and computerized Flight Management Systems. The progression from simple, manually operated equipment to semi-automatic machines was a story about to be re-enacted in many other fields, not least in the cars we all drive. My own unspectacular participation in the history of aviation had coincided with a revolution in technology. I had first-hand experience of the highs and lows of that revolution.

The accident rate had improved dramatically during my time, too. I couldn’t claim any responsibility for that improvement, but I had occupied the best possible seat from which to see it happen. I had taken part in the changes in working practices that were demanded during that revolution. People are still made out of the original model human being, with the same potential for brilliance and incompetence, but the way pilots go about their work is very different now from how it was when I joined an airline and I witnessed that change at first hand. When I reflected on the changes, I saw them as a war between skill and technology. Like all wars, it had destroyed some of the good along with the bad. What was needed for safe, reliable airline operation was a perfect blend of skill and technology. But skill had been annihilated. Technology had won the war against accidents and the depletion of human skill was collateral damage. Now we are seeing the consequences. Perhaps I had a story to tell after all.

* * *

I joined my first airline in 1967 and flew as an airline pilot continuously, except for two brief periods of unemployment, until 1998. As I get older, I begin to realize just how short a period of time that is. The rate of technical progress during that time seems incredible. Thirty-one years represented about one-third of the total history of aviation up to the time I stopped flying and nearly half of the history of airline flying.

The order for me to proceed to Berlin had arrived by telegram. Today, in the age of email and mobile phones, it is difficult to understand the fear that form of message could generate. The typed strips on the yellow paper, its buff envelope, the uniformed delivery lad on his red bicycle, all these were associated with bad news by my parents who had lived through the war in Coventry, bringing up my brother and myself during the tough years of air raids, rationing and shortages. Even more than twenty years after the war had ended, while they were proud of what I had achieved and pleased that I had got the job I wanted, they still had difficulty seeing aeroplanes as anything other than evil things that crashed or dropped bombs.

But times were changing. The piston-engined airliner was being abandoned as a transport system at just about the same time as the telegraph concluded its role in the world of communications.

It is not just the technology that has changed. The way people go about their jobs has changed, too. Speedy would not survive in an airline today; his uncommunicative arrogance and cavalier attitude to regulations would be unacceptable to management. Although still legally liable for the safety of the aircraft, its crew and its passengers or cargo, a captain today is allowed very little discretion. He is expected to make decisions by consensus, discussing problems with the first officer and cabin crew, and to consult with air traffic controllers, engineers and operations specialists by radio. Above all, the company’s Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) guide his every action. Even Speedy’s immense flying skill would atrophy in a fly-by-wire airliner where computers move the controls and the idea of disconnecting the autopilot is frowned upon. To me, even in 1967, Speedy was out of date, a relic.

Of course this happens, to some extent, in every field of human activity. The old generation must give way to the new. But in airline flying, a relatively new industry driven by technological progress, that ancient struggle is accelerated. New technology demands new attitudes. Pilots acquire new knowledge and learn new skills all the time, but attitudes develop more slowly and less consciously. While we can always learn how new technology works and master the techniques of operating it, our understanding of the job itself, our values and priorities, are informed by our previous experience. Attitudes are formed mainly in our teens or twenties and are resistant to change thereafter. So eventually, as the job changes, we get left behind.

No doubt the young pilots I flew with at the end of my career saw me as a dinosaur. It is an odd conceit we perpetuate when we imagine life evolving in a continuum from cavemen to spacemen. Our experience contradicts that model. Children take space travel, genetic modification and nanotechnology for granted and yet, by the time they come to retire, they will have become dinosaurs themselves. As individuals, we travel backwards from the cutting edge of technology to the Stone Age. So be it. The process has been necessary to turn airline flying into a safe, reliable transport system, but something has been lost along the way. When my memory sparks, the world I recall is more sensual and exciting than the sterile atmosphere of a modern airliner flight deck. I hear the rush of the real wind, not the roar of the air-conditioning system. And I remember characters whose skills and attitudes were forged in a more testing environment than the one ruled by Health and Safety regulations today.

In 1967, Europe – the world – was in a state of great change. The women’s liberation movement was at its height. Only the year before, Time magazine had featured London on its cover and dubbed it ‘the swinging city’. The birth-control pill had become available and in sex, art, music, fashion and philosophy, young people were challenging the old order. Berlin itself, the divided city, saw student riots mirroring those in Paris. But in our little world of airline flying, the revolution was more modest; it meant not calling the captain ‘Sir’. Our revolution was slower to take off, patchy and less dramatic, but it was there and it was serious.

Speedy didn’t seem to notice. I sometimes wondered if he would notice if I didn’t turn up for the flight. He was so self-contained that he would probably have done the whole trip without realizing that the right-hand seat was empty.

Toppling hierarchical structures seems to be a side effect of technology, so with the ongoing changes in the airline industry it would be surprising if tensions did not arise from time to time. Of course, new technology does not come into airlines as soon as it is invented; apart from the years of testing and development and the rigorous certification processes, there has to be a clear and pressing need for it. In commercial aviation the rules of survival are brutal. During the good times airlines can generate real money; fill the seats, charge high prices, keep the aircraft flying and all of the financial director’s dreams come true. When business is booming, turnover, profit and the all-important cash flow can reach levels that make other businesses seem pedestrian. But the good times do not come very often and they never last long enough. Ever since the first airlines were formed in the 1920s they have struggled with high overhead costs. There are few ways of losing money more quickly than an unprofitable airline.

So while there is a constant spur for more efficient aircraft, the money for new equipment is almost always tight. Older aircraft are rarely updated once they are in service. Unless a real financial benefit can be proved, with a short payback time, it is better to wait until it is possible to borrow against new aircraft. This means that many of the world’s airline pilots soldier on with relatively ancient aircraft for much of the time.

That’s why my first airline job was on a piston-engined freighter at a time when jets had been in service with some companies for several years. The outfit I joined was an anachronism, a hangover from the Berlin Airlift. The operation depended upon a single contract to carry fresh flowers, which the Berliners valued highly, from Amsterdam every day. Any other work that came along was a boost, but we stayed in business only by virtue of minimal costs and exceptional personal relationships between the principal businessmen involved. The shipper was used to us, knew we were reliable, and had enjoyed a long friendship with Herr Friedrich, the highly respected manager of our Berlin base. The directors of our parent airline back in the UK were more interested in scheduled passenger services, but they tolerated the Berlin operation because they could find no other work for the freighters. The two resident captains were both trainers and it provided an excellent training ground for new co-pilots.

I might have started on a more modern aircraft. A promised job with a UK airline operating Viscounts was withdrawn at the last minute and I had to chase around to find a sponsor for the Instrument Rating course I had booked with Tony Mack’s training school at Gatwick. I was offered an interview in Luton and dashed down the M1 in my old Ford Anglia, uncomfortably attired in my best suit.

Five minutes: that’s how long the interview lasted. I couldn’t believe what my watch was telling me. After all the years of dreaming, sacrificing and scheming, after all that studying, the written examinations, flying tests, raised hopes and hopes dashed, I got the job. The office, built on a gallery against the end wall of a hangar, had been tiny. The Chief Pilot and the Flight Operations Director had been squashed together at a little table. I had to squirm round the door and shuffle awkwardly into the chair facing them. And then I was standing outside again, five minutes later, looking down from the gallery on to the hangar floor where engineers were working on a piston-engined airliner. Not only did I now work for the same company as them, I was being paid to do my Instrument Rating training. The motherly secretary in the next tiny office promised to write to confirm the arrangements and wished me luck. It seemed too easy.

Of course, it hadn’t been easy. What was remarkable was that I had finally got through to people who made decisions, people who knew what they wanted and had the knowledge and confidence – and the cash – to make it happen, quickly. With the financial burden lifted the Instrument Rating training was a delight. Then came Berlin and real airline flying. I knew I was immensely fortunate to get into the business and, as the years have gone by, I’ve come to realize more and more just how lucky I was to start where I did on the Viking in Berlin. I was twenty-seven years of age and hungry for every scrap of knowledge I could glean about my new job.

CHAPTER 3

The Viking

The Vickers Viking had been developed from the wartime Wellington, mainstay of RAF Bomber Command, and many of the captains I flew with had learnt their trade on the original bomber. The changes were extensive; most of Barnes Wallis’s geodetic structure had been replaced by a more conventional stressed-skin construction, but, if you climbed up inside the engine nacelles and looked at the interior of the wing centre section, you could still see some of the diamond-shaped geodetic links. A stressed-skin shell of considerably wider proportions had replaced the bomber’s fuselage. The engines, wing planform, flight controls and systems had been retained, together with the undercarriage that was of the tail-wheel type. But the aircraft’s heart was in its engines; wonderful double-row, sleeve-valve radials giving 1,690 horsepower each and driving elegant, four-bladed, 12ft diameter constant speed propellers. It could cruise at 200mph, a high speed for its day, though its plump appearance led some people to suggest it was a fat version of the Douglas DC-3 and caused others to nickname it ‘The Pig’.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollst?ndigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollst?ndigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollst?ndigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollst?ndigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollst?ndigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollst?ndigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollst?ndigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollst?ndigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollst?ndigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollst?ndigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollst?ndigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollst?ndigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollst?ndigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollst?ndigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollst?ndigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollst?ndigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollst?ndigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollst?ndigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollst?ndigen Ausgabe!