22,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

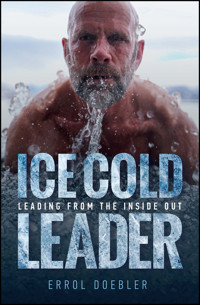

Thrive under any circumstances with insights from an elite combat veteran In Ice Cold Leader, special forces combat veteran, FBI agent, and business founder Errol Doebler reveals his unknown and silent battle with a traumatic brain injury incurred as a Navy SEAL in the late 1990s, and how he overcame emotional distress, self-doubt, depression, and anxiety to create a successful and happy personal and professional life until the day he discovered his pain was due to an injury he didn't even know he had. Anchored in gripping tales from his time in the elite services, the author describes the unique process he created to not only survive but thrive in challenging situations. In this illuminating book, you'll learn about: * Interrupting negative patterns and replacing them with new, constructive patterns * Developing tools to take on the stress of daily life without becoming overwhelmed by it * Using cold exposure and breathing exercises to improve overall quality of life Structured yet flexible, Ice Cold Leader delivers a unique process to improve your daily state of mind, meet personal challenges as they arise, thrive under difficult circumstances, and live your best life possible.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 356

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

PART 1: HOW I GOT HERE

PART 1: Prologue: What I Didn't Know Before

What You Will Get from This Book

CHAPTER 1: “We Were Sure You Were Dead”

CHAPTER 2: The Aftermath

CHAPTER 3: Getting the Call

CHAPTER 4: Within an Inch of My Life, Again

CHAPTER 5: Humiliation, Shame, and Silence

CHAPTER 6: For the Next Twenty Years …

CHAPTER 7: Fast Forward to 2020

CHAPTER 8: Long-Awaited Answers

The Next Steps Toward Recovery

PART 2: THE PROCESS

PART 2: Prologue

PART 2: Introduction

CHAPTER 9: The Leadership Process Overview … and Cold Exposure

Process Is Not a Four-Letter Word

Steps 1 & 2: Practice Emotional and Cultural Awareness and Recognition

Step 3: Create Guidelines for Behavior

Step 4: Implementing the Planning Process

Step 5: Meeting the Resistance

Finding Calm Amidst the Chaos

Note

CHAPTER 10: Element One—Emotional Awareness and Recognition

Emotions Influence Both Our Outer and Inner Worlds

The Importance of Self-Reflection

Where Do We Start?

Like It or Not, the Emotion Will Not Be Ignored

The (Potentially) Deadly Consequences of Unacknowledged Emotions

It's About the Conscious Decision, Not the Right Decision

Notes

CHAPTER 11: One Side of the Emotional Coin … Actions into Negative Consequences

Our Reactions to Our Emotions Are Just as Important

A Cautionary Tale

Enter “Tim”

What Has Happened So Far

“He's going to get killed!”

The Final Analysis

CHAPTER 12: Practicing the Other Side of the Emotional Coin … with an Ice Bath

Practicing the Art Through Cold Exposure

Note

CHAPTER 13: Element Two—Cultural Awareness and Recognition

Emotions Drive Culture

Does this Scenario Look Familiar?

Becoming Aware of Culture

The Elements of a Good Culture

The SEAL Teams: Sustainable and Transferable

Notes

CHAPTER 14: Observing Culture, Practicing Awareness … and Cold Exposure

My Early Exposure to the Culture

What Do Navy SEALs Do?

How It Translates

Focus on Observation Instead of Conclusions

Work Backward If You Like

Practicing the Art Through Cold Exposure

Notes

CHAPTER 15: Managing the Extremes and the In-betweens—Being in the Moment

The Science of Being in the Moment: You Don't Have to Be a Hippie

The Basic Effects of Being in the Moment or Practicing Metacognition

If You Are Not Present, Then You Are Somewhere Else

Do One Thing Well or Two Things Poorly

Now Extrapolate the Principle Out to Your Personal Life

Breathing and Cold Exposure to Practice the Art of Being in the Moment

The Cold, Too?

How Did That Coffee Shop Story End?

Notes

CHAPTER 16: Element Three—Guidelines for Behavior

Who Establishes Guidelines for Behavior and Why?

Establishing the Right Guidelines

Using the Leadership Data

Breaking Down the Behaviors in the Psychological Safe Zone

A Quick Thought on Enforcement

Emotional Sensitivity to Needs and Emotions

Notes

CHAPTER 17: Make Them Your Own—How to Define and Practice Guidelines for Behavior

Rules Set in Stone

The Approach, Fallout, and Effect

Making Guidelines That Stick

Best Practices Versus Guidelines for Behavior

How It Works at Home

CHAPTER 18: Implementing Your Guidelines for Behavior

Where to Start

How to Get Your Team Started

Too Many Is None

Practicing the Art

Choose a Behavior and Provide Context

When Everything Stays the Same, Nothing Changes

If You Change Things, Things Will Change

Notes

CHAPTER 19: Element Four—The Planning Process

Modified Navy SEAL Planning

SMACCC: “Situation”

SMACCC: “Mission”

SMACCC: “Actions”

SMACCC: “Command”

SMACCC: “Contingencies”

SMACCC: “Communication”

Thoughts and Considerations on This “Simple” Planning Process

CHAPTER 20: The Planning Process as a Leadership Tool

Instilling Initiative and Autonomy: Hear the Plan First

What If I Don't Like Their Plan?

Challenging the Plan and Still Letting It Be Theirs

I'm Afraid I'll Lose Track of What's Happening, but I Don't Want to Micromanage

More Bad Questions

It's Their Plan, Shouldn't They See the Problems?

SMACCC and Finding Calm Amidst the Chaos

But It's Not Always That Cut and Dry

CHAPTER 21: SMACCC! Your Brain Is Paying Attention; Rewiring and Prioritizing

Practicing the Art with Cold Exposure

Bringing It into the Office

SMACCC and Prioritization

The Challenge of Technology and Prioritization

Big Picture Prioritization and Biting Off More Than You Can Chew

Meeting Focus and Disputes

Put It to Work

Notes

CHAPTER 22: Element Five—Facing the Resistance

When the Resistance Hits the Team

Moving from Accountability to Consequence

Work the Resistance

Notes

A Final Note

Acknowledgments

Find Out More About

Ice Cold Leader

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

A Final Note

Acknowledgments

Find Out More About Ice Cold Leader

End User License Agreement

Pages

1

3

4

5

9

11

12

13

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

297

298

299

300

301

302

ICE COLD LEADER

LEADING FROM THE INSIDE OUT

ERROL DOEBLER

Copyright © 2024 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey.Published simultaneously in Canada.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 750-4470, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permission.

Trademarks: Wiley and the Wiley logo are trademarks or registered trademarks of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. and/or its affiliates in the United States and other countries and may not be used without written permission. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Further, readers should be aware that websites listed in this work may have changed or disappeared between when this work was written and when it is read. Neither the publisher nor authors shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

For general information on our other products and services or for technical support, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762-2974, outside the United States at (317) 572-3993 or fax (317) 572-4002.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic formats. For more information about Wiley products, visit our web site at www.wiley.com.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is Available:

ISBN 9781394239276 (Cloth)ISBN 9781394239610 (ePDF)ISBN 9781394239283 (ePub)

Cover Design: Olivier DarbonvilleCover Photo: © 2023 Jessica Jay

This book is dedicated to those who are on the never-ending search for self-improvement and personal excellence. Regardless of individual circumstance, injury, or trauma, personal and professional excellence will find you as long as you keep looking. Never quit, never give up, never stop searching!

PART 1HOW I GOT HERE

PART 1Prologue: What I Didn't Know Before

IN THE LATE 1990S, I SUFFERED TWO MAJOR HEAD INJURIES while operating as a Navy SEAL officer which led to my medical discharge. This was a difficult time for me because I loved being a Navy SEAL and had every intention of staying in the SEAL Teams for the duration of what I hoped would be a long military career.

The real shame in this is not that I lost a career I loved. As a result of these head injuries, I was unknowingly suffering from a silent injury called Traumatic Brain Injury, aka TBI, for over twenty years.

For those twenty-plus years, this injury wreaked havoc on my physical, mental, and emotional well-being. Bouts of depression, sleeplessness, and an uneasy relationship with who I was as a human being became my new normal.

In spite of my silent suffering, I managed to live an exciting and fruitful life.

The first edition of this book was written before I knew of my TBI. There was little to no context as to how or why I developed my leadership process and the role the wellness techniques played in my ability to thrive in spite of my injuries.

The severity of my TBI could very easily have placed me in the category of so many veterans today: as of this writing, twenty-two veterans commit suicide each day. But this didn't happen to me.

The process and wellness techniques I created for leadership and personal excellence literally saved my life. They allowed me to find peace in the chaos I was experiencing internally.

What You Will Get from This Book

Part 1 of this book contains stories I have never shared in detail before. They reveal things I did not know about myself and stories I swore never to share. The details of these stories will resonate with you because they represent the struggles we all face.

My hope is that you will be able to feel the pain I describe to you in Part 1—physically, mentally, and emotionally. Why? Because at one point or another, we will all feel physical, mental, and emotional pain. I want you to recognize that you are not alone and that there is a very structured way to move through these challenging times.

Pain and suffering is not a contest. Mine is not worse or better or more harmful than yours. It is simply mine. Our physical, mental, and emotional pain meets us where we are. I want to provide you with a way to handle your pain, no matter how simple or severe it may be.

I hope my stories will inspire you and show you that there is a way forward, even when you don't know why you are struggling. Sometimes knowing you are not alone is inspiration enough. You are not alone!

As you read this book, I want you to take an honest look at your own life and normalize some of the doubt, insecurity, and fear you face. It is OK to acknowledge these things. It does not make you weak. In fact, because it is so hard to do, acknowledging these parts of yourself only strengthens you. Greatness comes from doing the hard things, and being honest with yourself is a very hard thing.

Part 2 is the first edition of this book, originally titled The Process, Art, and Science of Leadership. When I originally wrote it, I had little to no context as to how or why my process worked. Part 1 gives us context. Part 2 gives us the process and the wellness practices to move through personal and professional challenges.

The context I provide in Part 1 along with the details of the process in Part 2 gives even greater credence to my leadership methodology. This book shows the importance of becoming an “Ice Cold Leader.”

CHAPTER 1“We Were Sure You Were Dead”

ONE OF THE COMBAT AREAS OF PROFICIENCY REQUIRED OF a Navy SEAL platoon is Military Operations in an Urban Terrain, or MOUT. This is simply the act of a military unit moving through a city and fighting, usually from house to house. This was typically the type of combat you saw on the news during the War on Terror in Iraq.

One night as my platoon was training, we set up on a house for entry, and I was to be the second man through the door. I would simply go the opposite way the “number one man” went. The number one man's nickname was “Booger.” (No secret meaning here. He always seemed to have a hanger disgustingly in view.) In other words, if Booger went through the door and turned right, I would go left. My job was to simply read off of him, go the opposite way, and continue on with the standard house-clearing protocols.

The movements of a proficient military unit making its way through the house are clear and distinct. If a SEAL decides he is going to go to the right, that's it. If it is the wrong move, it will be up to his teammates to make the necessary corrections to ensure a fluid and aggressive flow of movement through the house.

This is why I was surprised when Booger started to go left but then made a sudden jump to the right. It was an unusual display of uncertainty. Despite the speed at which we were moving, I remember clearly thinking to myself, “Huh, I wonder why he did that?” I was about to find out a split second later.

As I stepped to the left through the door's threshold and brought my weapon up to clear my area of the room, I suddenly found myself in a free fall. There was no floor as I entered straight through the door. This is what Booger saw and instinctively jumped away from. (As an aside, night vision goggles were not in play back then. We had flashlights on our weapons that we would turn on as soon as we passed through the threshold of the door. Hence, I couldn't see that there was no floor on the other side of the door until it was too late.)

I always felt bad for Booger—some of the guys gave him a hard time for not warning me. I put a stop to the teasing immediately because it was impossible for Booger to have warned me. We were moving too fast, and I was practically touching him as we went through the door.

I distinctly remember time slowing down as I fell and having a couple of things go through my mind. “Are you shitting me?!” was definitely the first thing. “I wonder how far this fall is going to be?” was next. And finally, “I wonder what is going to be on the floor when I eventually hit?” I was anticipating broken glass, jagged steel, or something awful waiting to make the fall worse.

It turned out to be about a ten-foot fall onto concrete. Not great, but much less bad than I was anticipating. I ended up landing forehead-first. The brim of my helmet shot up upon impact, which exposed my forehead and did not protect me at all. I recently reconnected with one of my teammates, and we had a couple of laughs over the incident. In a flash of seriousness, he relayed to me the sentiment of the platoon after the fall: “We were sure you were dead. The sound of your head hitting the ground was nauseating. We couldn't believe it when you got up.”

For better or worse, things were a little different back then when it came to head injuries (and injuries in general). After everyone had some fun looking at the new gash on my skull, we finished up some additional training before I was taken to the local hospital for stitches.

At the hospital, the doctor simply asked what happened and then stitched up my head. We couldn't have been in the hospital for more than an hour. In my medical record, there is a small slip of paper indicating that I was at the hospital. There were no notes from the doctor describing the injury or the treatment. To the best of my recollection, this was at my request.

The next day, I was back at training as if nothing happened. As far as I was concerned, the problem was not my head injury—it was my wrists. After we got back from the hospital, I went to our platoon corpsman's room and told him my wrists were in terrible pain. One light touch of his finger to both wrists gave him all the information he needed. “They're broken, sir. No question about it. What do you want to do?”

Obviously, we weren't going to go back to the hospital because if they cast my wrist, there was a chance I would be removed from the platoon. That was not going to happen. In my mind, my biggest challenge was going to be operating for the next year with broken wrists. So, a couple of ace bandages and some painkillers later, along with some good ole Frogman grit, problem solved. Or at least that's what I thought. As it turns out, my wrists were the least of my problems.

CHAPTER 2The Aftermath

ABOUT TWO WEEKS AFTER MY FALL, MY PLATOON WAS practicing climbing a caving ladder. We rigged up the ladder to a ship docked in port, jumped in the water, and climbed it. The goal was to get the platoon up the ladder and on board the ship as quickly as possible.

An hour or so into the exercise, as I was treading water waiting for my turn to climb the ladder, I started to feel incredibly sick. The headache and nausea hitting me were like nothing I'd ever experienced. I got up the ladder, and before we went back in the water for another repetition, I told my assistant platoon commander to finish the training. I just needed to sit down for a minute. He gave me an inquisitive look but agreed and went on with the training.

I immediately found a spot to curl up in the fetal position. My head hurt so badly that I literally could not move or speak. I heard my platoon debriefing on the ship about fifteen feet from where I was lying. I heard someone ask where I was. Then, I heard the men gathering up their gear to leave. I was sure I was going to be left there for the night—I was in so much pain I couldn't even yell for someone to help me. Fortunately, one of the men noticed me. The next thing I remember is being in the hospital.

I was able to tell the hospital staff what happened and how I felt. They gave me an IV and some medication to relieve the pain. I stayed in the hospital the rest of the night and vomited the entire time. In the morning, some men from the platoon came to get me from the hospital after I was discharged.

As they helped (carried) me through my apartment complex, I had to stop several times to vomit. Many residents were sitting on their porches having their morning coffee, shaking their heads in disgust at what looked like a stupid young man experiencing the effects of a wild night and too much alcohol. I remember feeling strangely humiliated.

The men from my platoon got me to bed and encouraged me to rest, take the medication the hospital provided, and call them if I needed anything. I remember being relieved it was a Thursday or Friday morning because I would have the weekend to rest and recover.

I took the medication provided, and I immediately knew I was in trouble. I felt even worse. All I could do was lie in bed. I could barely speak, and I certainly wasn't able to get up to get some water.

I had a couple of roommates, but I was gone so often during pre-deployment workup that they never thought anything of the door to my room being closed. They just assumed I was out of town again. I remember thinking to myself that I actually might die in my bed if someone didn't recognize that I was still in there.

Thankfully, my parents knew I was in town. They hadn't heard from me in a few days, which was out of the norm, and called my roommates to check and see if I was in my room. Finally, after about two and a half days of lying in bed with nothing to eat or drink, I was discovered!

I say this lightheartedly, but I honestly remember thinking at some point, “I'm not really going to die in this bed with people walking outside my door all day, am I?” I remember feeling both amused and disturbed at the same time.

I was taken back to the hospital where I was told that the medications were working against each other somehow, and that was the cause of my adverse reaction.

I told the hospital staff that the medication didn't cause the massive head pain I was feeling. They simply replied that the medication certainly didn't help my situation.

Nobody could explain what was happening to me. Nobody asked about or knew about my head injury weeks earlier. It was all a mystery. I spent a week in the hospital and endured three spinal taps. The first two showed an abnormal amount of blood in my spine, and I was told I would be held in the hospital until the spinal tap came back normal.

Thankfully, the third spinal tap came back normal. I was subsequently discharged and sent home. It was the week of Thanksgiving break, so I was given a few days off for convalescent leave and asked if I was ready to get back to work on Monday. Like any good Frogman, my answer was yes.

The headaches never really went away, but I pressed on without complaint.

CHAPTER 3Getting the Call

DESPITE THE UPS AND DOWNS I EXPERIENCED DURING OUR eighteen-month pre-deployment workup, I was excited to deploy as the platoon commander of a sixteen-man platoon for six months as part of an Amphibious Readiness Group (ARG).

At the time of our deployment in the late 1990s, the United States was in a time of relative peace. It's always a great time to be a SEAL, but as far as work went, pickings were slim. By work, I mean the only work that matters to a Navy SEAL: combat. But we were ready to fight should we get the call. As part of the ARG, we were scheduled to travel to various countries throughout Africa and the Middle East and, should the need arise, meet the call for combat on land or sea in that battle space. The members of the platoon and I had no illusions, though. The likelihood of getting the call to fight was remote at best.

And then, unbelievably, it came. A cargo ship had been identified carrying cargo it was not supposed to be carrying while traveling to a country to which it should not have been traveling. The platoon was tasked with taking down the cargo ship. A Visit, Board, Search, and Seizure operation. VBSS! A classic Navy SEAL operation that the SEAL Teams do better than anyone in the world.

The operation was scheduled to take place forty-eight hours from tasking. This was perfect because it allowed us one day to rehearse, which is not always an available luxury. The platoon could have done the operation without a rehearsal if necessary, which is the very reason we spent eighteen hard months training prior to deployment. Regardless, we were grateful for the extra day to rehearse and plan. However, there was a problem. In the words of the immortal Seinfeld character George Costanza, “The sea was angry that day, my friends—like an old man trying to send back soup in a deli.”

All joking aside, the seas were incredibly rough and looked to present a real problem to the operation. Believe me, when a group of Navy SEALs look at the ocean and start to question whether it is possible to conduct an operation, that's saying something. Some of the senior members of the platoon and I looked over the ocean and discussed the potential problems the heavy seas could cause the operation. After some intensive discussion, I felt we had rolled it over enough, “There's only one way to find out. We have the luxury of a rehearsal day, so let's go rehearse.”

I made my way up to the bridge of the ship to discuss our launch for rehearsal with the commanding officer of the ship. As I began to relay my recommendations for the rehearsal, he stopped me mid-sentence and said, “You aren't really thinking of launching your boats in this weather, are you?” When I told him that, yes, we were planning on launching to rehearse he replied, “I won't allow it. It's unsafe.” So, I replied, “I understand, sir. If the weather holds and is like this tomorrow, will we be authorized to launch for the operation?” “Yes,” was his response.

I stood quietly after he confirmed that he would launch the platoon for the operation in the very weather he would not allow us to rehearse in because it was too dangerous. I could literally feel the unspoken conversation we were having. I could feel him comprehend what I was silently saying: “You can't prevent us from rehearsing in the very weather in which you would willingly send us into harm's way.”

After a few seconds of this silent exchange, he asked, “How long before your platoon can be ready to launch for rehearsal?”

“The boats and the platoon are ready, sir. The men are just waiting for me to suit up.” With that, we were ready to rehearse.

The purpose of a VBSS operation is simple. Board and take control of an enemy ship before anyone on that ship has a chance to respond to your presence. Even in perfect conditions, it is a challenging operation.

The sixteen platoon members would be split between two Rigid Hulled Inflatable Boats (RHIBs). A RHIB is a high-speed, high-buoyancy, extreme-weather craft with the primary mission of Navy SEAL insertion, extraction, and VBSS. They are about thirty-five feet in length and can travel forty-plus knots with a range of approximately 200 nautical miles.

The first (and arguably most important and difficult) portion of the VBSS operation is to secure the caving ladder to the target ship so the SEALs can climb it to board the target ship. A caving ladder is a lightweight, sturdy ladder that can be rolled up. It is about six inches in width, weighs about four pounds, has a breaking strength of over 1,300 pounds, and is generally about thirty-two feet long. Its cables are made of steel, and the rungs are generally lightweight aluminum.

The general concept of this portion of the VBSS operation is to attach one end of the caving ladder to a large grappling hook. Then that large grappling hook is attached to a collapsible pole that can extend to about thirty feet. To get your grappling hook attached to where you want it on the ship you are about to board, you get your biggest, strongest SEAL to heave the pole to the top of the ship to a place where the grappling hook can latch on. A difficult task in perfect conditions.

Once the grappling hook is secured on the target ship, the SEAL operator disconnects the pole with a mighty pull and brings it back onto the RHIB. The caving ladder naturally unfolds when the pole and caving ladder are hoisted to the connection point of the ship. Now, you replace your biggest, strongest SEAL with your smallest, fastest SEAL, who is likely your best climber.

Your best climber acts on faith that his teammate securely hooked the grappling hook to the ship and climbs to the top. Once he is safely on board the target ship, he ensures the grappling hook is safely secured so the rest of the team can safely climb the ladder and begin the takedown of the ship.

This is all done while the RHIBs and target ship are moving at speeds that could be as high as twenty-five knots. To do this successfully, the RHIB must maintain a steady positioning from the target ship. This distance between the RHIB and the target ship can vary, but it needs to be as close as possible, typically a body length or so.

As I said, even under the best conditions, VBSS is a challenging operation to execute. On this rehearsal day, the sea conditions were far from perfect, but we were ready to rehearse so we could ensure a smooth operation the following day. Just as importantly, we were also ready to explain to higher authority why we would not be able to conduct the operation in the current weather state.

As soon as the RHIBs were launched for rehearsal, and we were at sea, I knew we were pushing the envelope of safety, even for Navy SEALs. We would be practicing our boarding on the same ship we were stationed on, which, reportedly, was about the same size as the cargo ship we were to be taking down the following day.

I instructed the RHIB coxswains to conduct several large, looping maneuvers to get a feel for the heavy seas before we approached the target ship. More than anything, I wanted to get a feel for their demeanor. Did they appear overwhelmed and in over their heads, or were they acting methodically and professionally? If they were skittish in the open sea, there was no way I was going to allow them to approach the target ship and attempt to maintain a steady, but close, distance. The coxswains of both RHIBs could not have been more than twenty years old, but thus far, the coxswain on my RHIB was conducting himself with the poise and professionalism expected of a warrior driving SEALs to a target. I radioed over to my chief petty officer on the other RHIB and asked, “How does he look?” His response regarding his coxswain was brief and to the point: “Solid.”

Despite the coxswains' solid handling of the RHIBs, my concern was that we were catching too much air. Catching air while trying to maintain station next to the target ship is a recipe for disaster and a “no-go” criterion. I had the coxswains slow down and note the top speed at which we could travel without catching air.

I instructed my RHIB to approach and maintain station until I ordered him to break away. I had to focus my attention on not only the coxswain's demeanor but his skill. As we approached the target ship and began to pull alongside, there was a deafening silence falling over the squad. “Holy shit,” I thought to myself, “this is a little scary looking.”

As we approached, we were able to see below the waterline of the target ship as it crashed through the waves. In fact, we were able to see far below the water line. This could mean disaster if the RHIB got too close and maneuvered into the huge swell created by the target ship. Could we possibly get sucked into the target ship? I could not even fathom how that would look or how awful it would be if it happened.

I took position next to the coxswain and told him what I wanted from him: “This is dangerous enough, so we are not here to take any unnecessary chances. We are here to see if we can perform the operation in this sea state. If we can't, we can't. It is not a big deal. We go back and wait for another opportunity.” My primary purpose here was to ensure the young coxswain took his ego out of what we were doing. I did not want him to think that the fate of the operation was on his shoulders. I wanted to assure him that it was not a big deal if we could not do the operation.

“Can I trust you to get only as close to the ship as you feel safe and not an inch closer?”

“Yes, sir,” he replied with the confidence I was looking and hoping for.

The coxswain approached the target ship confidently and quickly found his safe distance. We were close enough to get the caving ladder attached and have the platoon climb and board the target ship. Now the question was how long the coxswain could maintain station. I instructed him to keep station until I told him to break away. This amounted to several minutes on station.

While this was happening, I then asked the operator who would be throwing the caving ladder what he thought. Would he be able to do his job safely in this sea state?

“I think it'll be OK, sir. But I don't know if the pole is long enough to reach where we need to attach the grappling hook.” That meant our climb would be at least thirty feet.

“Do you feel comfortable giving it a try?” As with the coxswain, I assured him that it was not a big deal if he did not feel comfortable. It was not a reflection on his abilities. He had to be honest for the good of the entire platoon. He was a seasoned operator and understood what I was saying.

“I can get it up safely,” he calmly told me.

“Roger,” I responded.

After several minutes of safely holding station, I instructed the coxswain to break away and ordered the other RHIB to take their turn and report back. I could watch the other RHIB from a distance but could not monitor the feeling and vibe on the boat. I had to rely on the chief for that.

The chief of the platoon was excellent, and I trusted him implicitly. He understood the line we were toeing between aggressiveness and safety and would take everything into account as he reported back.

SEAL platoons operate differently in many regards to other combat units. As the leader of the platoon, it was my job not only to make the decisions of safety and aggressiveness that I have described but also to lead from the front. If that means being among the first to launch into a dangerous situation, so be it.

It is not an indictment or judgment on other combat units where the officer places him- or herself somewhere in the middle of the unit. There is merit to that strategy; it just was not the go-to for SEAL platoons. So, the question I was pondering as I watched the second RHIB go through the paces was, “Where is the last place I want to be as we conduct this operation?” Wherever that place was, that was where I needed to be.

In this case, while I would normally be the second or third man up the ladder, the best place to be was off the RHIB and on the ladder. It was uncomfortable, to say the least, waiting for your turn to climb while the RHIB maintained station. I felt it was important to monitor the safety of the evolution and be in a position to make decisions should something go wrong. But, God knows, I wanted to be up that ladder and off the RHIB!

With that in mind, after the chief reported back that his RHIB was good to go, I advised him that we were going to switch the order of the boarding. I would be the last one to leave the RHIB.

I radioed the chief and told him he was the lead boat. Everything else remained the same. “Roger,” he replied. Then, the typical SEAL sense of humor kicked in: “Enjoy the long ride,” he sarcastically radioed back. I knew it was his way of saying, “Thanks!” And then I gave the order, “Execute, execute, execute.”

In any SEAL operation, contingency planning is vital. While we always planned for the actions we needed to execute for success, we also had to act with the realization that things go wrong. Contingency planning involves identifying those things and accounting for them.

Some contingencies are running contingencies, meaning you always account for them. An example is radio communications going down. “What will we do if we lose communications between squads or with higher authority?” The answer will vary from operation to operation, but the contingency is always accounted for.

I had a personal theory around contingencies that I developed from experience and in speaking with some of the senior SEALs who had combat experience from Vietnam. While we were always prepared to execute any contingency plan, you had to take note of how many contingencies you were forced to execute. In other words, operations are hard enough when they go smoothly or without executing contingencies.

Bad things have a way of snowballing. Anything going wrong naturally disrupts the operation. Two things going wrong can disrupt the operation doubly. Three things going wrong … well, you get the point. My personal rule of thumb around contingencies was that the third major contingency you experience during an operation was likely someone getting killed. As a leader, I felt I had to be hyper-conscious of where we stood in an operation if a series of contingencies had to be executed.

For this rehearsal, my contingency radar was on high. If two things went wrong, I was prepared to abort the operation so the third bad thing wouldn't happen—and so no one would get killed.

The trouble started almost immediately when I lost radio communications with the other RHIB. We seamlessly executed our contingency for this possibility, and I made a mental note: “That's one.”

We quickly got our radio communications back, and I thought to myself, “Does that still count as a contingency since we got our communications back so quickly? Yes, it does,” I concluded.

And then the call came from the chief as they were about to throw up the caving ladder: “The pole just broke. I recommend you take back the lead as we fix the problem.” That was enough for me. We had not even started the process of boarding, and already, two major contingencies had to be executed. With the weather the way it was, things were not going to be getting easier. “Abort, Chief. Let's bring it in.”

Immediately, the chief radioed back, “The pole is fine, my bad. We're good to keep going.”

My mind was racing. Was that two contingencies? One? One and a half? I had to quickly turn to what I would do if this was the actual operation. I made the call: “OK, continue on, Chief.”