Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Returning to the UK in September 2010 after serving in Iraq as the political adviser to the top American general, Emma Sky felt no sense of homecoming. She soon found herself back in the Middle East travelling through a region in revolt. In A Time of Monsters bears witness to the demands of young people for dignity and justice during the Arab Spring; the inability of sclerotic regimes to reform; the descent of Syria into civil war; the rise of the Islamic State; and the flight of refugees to Europe. With deep empathy for its people and an extensive understanding of the Middle East, Sky makes a complex region more comprehensible. A great storyteller and observational writer, Sky also reveals the ties that bind the Middle East to the West and how blowback from our interventions in the region contributed to the British vote to leave the European Union and to the election of Donald Trump as president of the United States.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 414

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

In a Time of Monsters

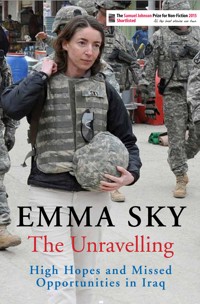

Emma Sky is a Senior Fellow at Yale University’s Jackson Institute. She worked in the Middle East for twenty years and was made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire for services in Iraq. Her first book, The Unravelling, was shortlisted for the Samuel Johnson Prize, the Orwell Prize and the CFR Arthur Ross Book Award. She lives in New Haven, Connecticut.

By the same authorThe Unravelling

In a Time of Monsters

Travels Through a Middle East in Revolt

Emma Sky

First published in Great Britain in 2019 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition first published in Great Britain in 2020 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © Emma Sky, 2019

The moral right of Emma Sky to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Lyrics from Like a Rolling Stone by Bob Dylan are reproduced by permission; copyright © 1965 by Warner Bros. Inc.; renewed 1993 by Special Rider Music.

Except where noted, all photographs are taken by the author.

Map artwork by Jeff Edwards.

E-book ISBN: 978-1-78649-561-7

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-78649-562-4

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For fellow travellers

The old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born: now is the time of monstersAntonio Gramsci

Who lives sees, but who travels sees moreIbn Battuta

CONTENTS

Preface

Map

Prologue: What had it all been for?

1Hold your head up, you’re an Egyptian! Egypt, May 2011

2Dégage! Tunisia, June 2011

3‘Assad – or we burn the country’ Syria, July 2011

4They are all thieves Iraq, June 2011 and January 2012

5Zero neighbours without problems Turkey, October 2012

6Better sixty years of tyranny than one night of anarchy Saudi Arabia, December 2012

7… to the hill of frankincense Oman, December 2012

8We have no friends but the mountains Kurdistan, July 2013

9... but surely we are brave, who take the Golden Road to Samarkand The Silk Road, June 2014

10The Islamic State: A caliphate in accordance with the prophetic method Jordan, March 2015

11What happens in the Middle East does not stay in the Middle East The Balkans, January 2016

12And even though it all went wrong Britain, June–July 2016

Epilogue: The sun also rises

Acknowledgements

Index

Preface

A new Middle East constantly struggles to be born. But each attempted birth is abortive, with visions of utopia replaced by dystopia. After two decades of working in the region, I set out to make sense of the great upheavals taking place. Between 2010 and 2016, I travelled from Tahrir Square in Cairo to the Qandil mountains in Kurdistan; from the markets of Damascus to the marshes of Mesopotamia; from tea shops in Antakya to shopping malls in Saudi Arabia; from pyramids to petroglyphs; from the Persian Gulf to the Dead Sea to the Mediterranean; from Baghdad to Bukhara; from Khartoum to Carthage; from mosque to church to synagogue. I witnessed how dreams of new political orders based on rights and justice were shattered in wars and fragile states – and demons unleashed upon the world.

The overthrow of Saddam Hussein’s authoritarian regime in 2003 by a US-led coalition did not herald a new regional democratic order as envisaged by its Western architects. Instead, Iraq’s civil war sowed disorder beyond its borders. Furthermore, the collapse of the Arab counterweight that kept the Islamic Republic of Iran in check upended the balance of power in the region, fueling competition that continues to destabilize the Middle East.

The ‘new’ Iraq remains hamstrung by weak institutions and kleptocratic elites. Poor public services and rampant corruption have led to cycles of protests, violence and insurgency against the government. Elections are held regularly, but have not brought about meaningful change. Despite not winning the 2010 elections, Nuri al-Maliki, a Shia Islamist, still secured a second term as prime minister and subsequently marginalized his Sunni political opponents, consolidated power and implemented sectarian policies. This created the conditions that enabled the Islamic State – otherwise known as Daesh, or ISIS – to rise up out of the ashes of al-Qaeda in Iraq and proclaim itself as the protector of Sunnis.

In 2011, the youth of the Middle East sprang up in squares and streets across the region to protest injustice, call for better governance and demand jobs. However, sclerotic regimes proved incapable of reform. They either clung on to power or collapsed.

In Syria, the violent response of President Bashar al-Assad to the peaceful protests propelled the country’s descent into civil war. He falsely proclaimed that he was the only bulwark against terrorism – and through his use of terror he made his prophecy come true. The United States and its allies called for Assad to go – but gave minimal support to force his departure. Segments of the Syrian opposition took up arms and sought external support in their domestic conflict. Turkey, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Qatar provided weapons and funds to competing Sunni groups. Iran deployed its military advisers, as well as Shia militias from Lebanon, Iraq and Afghanistan, to prop up Assad’s embattled regime. Russia supplied it with air power.

Iraq and Syria became one battlefield. The lands once renowned for prophets, laws and the first organized states became synonymous with sacralized conflict, evil and anarchy. Black-clad figures – poisonous seeds germinated by corrupt elites and nourished by external intervention – planted the flag of Daesh in cities, souqs and saharas. Ancient trading metropolises, centres of culture and cosmopolitanism, were reduced to rubble. Thousands were decapitated or enslaved in the wake of a caliphate intent on imposing an austere, intolerant, patriarchal monoculturalism – the fantasy of fundamentalists throughout the ages.

A US-led coalition mobilized to counter ISIS. In 2016 alone, the US dropped 24,287 bombs on Iraq and Syria. The military campaign crushed Daesh – but it also destroyed cities, killed thousands of innocent civilians, enabled the proliferation of militias, shored up autocratic regimes and facilitated Iran’s development of land corridors across Iraq and Syria to Israel’s borders.

The outflow of refugees and terrorism from the Middle East contributed to the British vote to leave the European Union and the rise of Donald Trump, whose tirades against Muslims and immigrants – and pledges to protect Americans from ISIS, the bastard child of the Iraq War – helped propel him to the White House.

Pax Americana is dying; America’s post-Cold War triumphalism crashed and burned in the Middle East. The very notion of an international community has waned and withered. The Iraq War was the catalyst of this decline; the failure to stop the bloodshed in Syria the evidence. The international system is transitioning from a unipolar to a multipolar world, with the Middle East one of multiple competing spheres of influence. A revanchist Russia seeks to weaken the US-led liberal world order by supporting Assad in Syria and flooding the European Union with refugees fleeing its aerial bombardment. A rising and dissatisfied China pursues ‘One Belt, One Road’ for the acquisition of minerals and energy, building infrastructure including oil and gas pipelines across the region. Middle Eastern powers, for their part, are adjusting and competing to shape a regional order in flux.

In a Time of Monsters relates my encounters with young people calling for reforms and others seeking revolution; insurgents willing to die for a cause and ordinary citizens simply seeking to live in security; pilgrims walking to Karbala and refugees headed for Germany; and Western diplomats trying to mediate peace overseas while polarization increases back home. It endeavours to contribute to a better understanding of a region in transition during a time of changing world order. In writing In a Time of Monsters, I hope to encourage others to explore the unknown, build bridges, and be fearless seekers of our common humanity.

If the book imparts any of the virtue and value of travel, then it has served its purpose.

In a Time of Monsters

PROLOGUE

What had it all been for?

…how does it feel?

To be on your own, with no direction home A complete unknown

Bob Dylan

I had not told anybody I was coming home.

There were no direct flights from Baghdad, so I hung out for a few days in Istanbul before flying on to London. I unlocked the front door of my house in Battersea and walked straight over the mountain of mail. The air was musty and stale. I opened the shutters in the living room to let in the light, and then threw open the back door for fresh air. I walked around the house, taking in the black-and-white photos of the Old City of Jerusalem, the rugs that I had brought back from Afghanistan, the prints from Egypt and Yemen, the Armenian pottery, the Moroccan tagine and the books stacked on the shelves. This was my home, full of my belongings and the mementos I had collected in faraway places.

The house was neglected and cold. But it felt safe. A refuge after years working in war-torn Iraq.

I texted Daniel Korski that I had just got back. Korski was born in Denmark to Polish Jewish refugees, had long since made London his base and had been involved in initiatives to stabilize countries post-conflict, including in Iraq and Afghanistan. He invited me to meet up with him that night at a pub in Notting Hill. So, a couple of hours later, I was drinking wine and deep in discussion with Korski and his friend, Tom Tugendhat, an army officer. Conversation was easy and animated – we had our wars to talk about and government policy to chide.

At the end of the evening, Tom gave me a ride across London on the back of his bike. Giggling and drunk, I managed to cling on to his waist as we cycled down the Portobello Road and into Hyde Park, past the memorial to Princess Diana and along the Serpentine. He dropped me off at the bus stop near Wellington Arch.

The next morning, I went to my local Sainsbury’s supermarket to stock up on food. What did I want to eat? I didn’t know. I hadn’t cooked myself a meal in years. Did I want full-fat, half-fat or skimmed milk? Did I want free-range, corn-fed, organic or caged eggs? Did I want white, brown, wheat, wholegrain, thin-, medium- or thick-sliced bread? Marmite. I wanted Marmite. And at least with Marmite I didn’t have to choose between different brands – there was only one. And Heinz beans. I would eat Marmite on toast, beans on toast and boiled egg on toast until I felt more inclined to cook.

*

In the weeks after my return, I was not sleeping well. I would wake up anxious in the middle of the night. I had no job, no income, no direction.

I took an inventory of my situation. I was in good health. I had a house to live in – and some savings to live off. I had friends. But the only people I connected to were those who had been to war. Here in London, I was bored. No one needed me. I had nothing to do.

I had no idea what I wanted to do next.

*

Most of my adult life had been spent in the Middle East. I fell in love with the region the first time I set foot in it, aged eighteen. I found something there that was lacking in the West. The warmth, the interconnectedness, the sense of belonging, the history.

It was in the Middle East that I discovered a sense of purpose, a passion for promoting peace.

My interest in the region had been sparked during a gap year spent working on a kibbutz in Israel. The secularism and socialism of the kibbutz was a stark contrast to the Christianity and conservatism of Dean Close, the British boarding school in Cheltenham that I had attended on scholarship. While by the 1980s many kibbutzim had become privatized, Kfar Menahem still held on to the vision of its founders.

I was assigned to work in the cowshed. I got up at dawn to milk cows, and at night I gathered around the campfire with young people from all over the world, discussing the meaning of life and how to bring about world peace. To me, it appeared an ideal community, where people from different backgrounds lived in harmony, with each person contributing what they could and receiving full board and lodging in return. I observed how, in a safe and equitable environment, people of different cultures could co-exist. The experience – at such an impressionable age – turned me into a humanist. Having been accepted to read Classics at Oxford, I changed course to Middle East Studies at the end of my first term, when the first Palestinian intifada broke out.

I spent the nineties in Jerusalem working in support of the Middle East peace process, managing projects on behalf of the British Council with the aim of building up the capacity of the Palestinian authority and fostering relations between Israelis and Palestinians. But by 2001, the Oslo Accords faltered and then failed, and the second intifada was in full swing. The projects I had been working on closed down, and I returned to the UK.

Although opposed to the 2003 Iraq War, I responded to the request of the British government for volunteers to administer the country after the invasion. I wanted to go to Iraq to apologize to Iraqis for the war, and to help them rebuild their country. My assignment was only supposed to be for three months – but it ended up spanning seven years. I found myself governing the province of Kirkuk, and then going on to serve as the political adviser to the top leaders in the US military.

While I had gone out to Iraq in June 2003 on secondment from the British Council, to continue working there I had to resign from my permanent and pensionable job and move on to short-term consultancy contracts – initially with the UK’s Department for International Development, and then, after the British government withdrew its forces and lost interest, with the United States Army. And so on my return to the UK in September 2010, I was no longer part of any organization. No one in British officialdom showed any interest in me or what I had been doing. As a civilian returning from war, there was no parade or band – or even a debriefing.

I did not feel any real sense of homecoming. London was alien to me. I could not cope with congested streets and overcrowded shops. I jumped at loud noises. I looked for escape routes. I was hyper-aware, constantly scanning for suspicious-looking people. With so many different styles and cultures in London, I could not tell who looked out of place. Many people looked odd to me – some very odd!

I found it hard to concentrate or to sit still. I tried reading books, and my eyes went over the lines, page by page, but I retained little. When I reread a paragraph, I had no recollection of having seen it before.

I searched the Internet for news of Iraq. I sent emails and text messages via Viber to Iraqi friends, eager to hear from them, to check that they were still alive, to tell them I was missing them.

I felt like an Iraqi exile, yearning to be back in Baghdad.

*

Every morning, I jogged around Battersea Park. On one occasion, as I was stretching after my run, I spotted a young man with two prosthetic blade-runner legs. He had the upright demeanour of a soldier, so I approached him.

‘Hey, how did you lose your legs?’ I asked casually, as if it were no big deal.

‘I stood on a bomb,’ he responded, while miming the explosion with his hands.

‘Iraq or Afghanistan?’

It had been in Helmand, Afghanistan. The province that had taken the lives and limbs of numerous British soldiers and US marines. I told him I had served in Afghanistan in 2006 with ISAF (NATO’s International Security Assistance Force), and in Iraq before and after. We shook hands and introduced ourselves. He told me his name was Harry Parker, a captain in the Rifles regiment.

After we’d been chatting for a while, he asked if I had ever met his dad, General Nick Parker. I had not. But we soon realized that we had someone in common: his father’s close friend, General Sir Graeme Lamb, the former head of the SAS. ‘Lambo’, as he was generally known, had retired to the countryside. But he had got in contact with me on my return to make sure I was doing OK and we had met up for a drink. He’d told me all about Harry and how well he was coping with his injuries. And here in Battersea Park, by chance, Harry and I had met.

Harry told me he was trying out his new running legs. It was not easy to balance on them at the beginning. It took time, he explained, as he rocked back and forth. His eyes sparkled, and he was quick to smile, masking the pain and suffering he had been through.

‘When you see Lambo,’ I said, ‘tell him I beat you running!’

Harry grinned. In previous years, a mixture of awkwardness and embarrassment would have deterred me from speaking to someone with prosthetic legs. I would not have had any connection to them, would not have known what to say. But now, all around me, I saw veterans of our wars, returning reshaped by their experiences, many confident and proud but some as fragments of their former selves. It was veterans I could relate to the most.

When I got home from the park that day, the tears started to pour down my face. And then I broke into deep sobs.

What had our wars been for?

*

I continued to mope around at home, wondering how I was going to find new purpose, to rekindle my passion for life, to feel part of something bigger than myself.

My tried-and-tested method of rebooting was to go on a trip. I had been interested in travel for as long as I could remember. I loved the research, the poring over guidebooks and examining maps. As a child, my imagination had been sparked by Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, photos in the National Geographic, and the memoirs and biographies of adventurers who had sought the sources of rivers or scaled uncharted peaks.

Travelling solo to distant lands was the ultimate challenge. I’d started off with trips of two to four weeks, and built up to journeys that lasted months – then, after university, years. Each time I set out, I felt sick with anxiety. But with experience, I grew more confident in embracing uncertainty and coping with whatever was thrown at me.

I knew I needed to get away from the UK. I needed a distraction, to go somewhere that promised adrenaline and adventure, new places and faces. So I approached the Sudanese embassy in St James’s in London for a visa. During my interview, the consular official asked me why I wished to visit his country. The embassy did not receive many requests for tourist visas, as Sudan was under international sanctions and the UK government’s travel advice did not encourage visits.

It did not seem appropriate to confess that I was bored, bitter and twisted – and that Sudan promised escape and escapades. I responded that I had read Season of Migration to the North by the Sudanese novelist Tayeb Salih, and wished to visit the homeland of the great author. The consular official smiled, and stamped a visa into my passport.

Two months after my return from Baghdad, I packed a small red rucksack, walked out my front door and got on a plane to Khartoum.

*

Bilad as-Sudan, the Land of the Blacks. Here was a country of dust and danger, of blue skies and yellow sands, a place I had never visited before but which in so many ways felt familiar. My senses were reawakened by the sound of the muezzin calling the faithful to prayer, the sight of merchants in markets and the smell of kebab. I felt alive again.

I went out to Omdurman, a city on the west bank of the Nile facing Khartoum, to visit the camel market. Hundreds and hundreds of camels for sale, along with sheep and goats, all congregated on the edge of the desert.

‘Hello khawaja!’ a trader shouted out to me. I was the only white person, and a source of great interest.

When I shot back a response in Arabic he invited me over, giving me a white plastic chair to sit on before pouring me a cup of well-sugared tea. ‘Where are you from?’ asked the trader, who was wearing a white jalabiya (thobe) and a white imama (turban).

‘England. Britain,’ I responded.

‘Ah, Gordon Pasha,’ he said, with a grin that revealed a half dozen teeth. ‘We killed him!’

I smiled back at the reference to Gordon of Khartoum. When travelling, my identity was typically reduced to my nationality, with all the history that it evoked. In the late nineteenth century, London had appointed General Gordon – renowned for putting down the Taiping Rebellion in China during the Opium Wars – as Governor-General of Sudan, where he worked to suppress revolts and eradicate the local slave trade. In 1884 he was instructed by London to evacuate Khartoum, but instead hung on with a small force. Mohamad Ahmed bin Abd Allah, who had pronounced himself the Mahdi (the prophesized redeemer) and declared jihad against foreign rule, besieged Khartoum with his fundamentalist followers. General Gordon was hacked to death on the steps of the palace. The Mahdi ordered his head to be fixed between the branches of a tree.

After the Mahdi’s death from typhoid six months later, his three deputies fought among themselves until one emerged as al-khalifa, the caliph, seeking to further the vision of the Mahdi through jihad – under the banner of black flags. In 1898, General Kitchener defeated the caliph at Omdurman, mowing down with Maxim guns the Mahdist soldiers who were armed only with spears, swords and old rifles. Avenging the murder of Gordon, Kitchener ordered the destruction of the tomb of the Mahdi and for his bones to be thrown into the Nile. Winston Churchill, a young army officer at the time, was scandalized by Kitchener taking the Mahdi’s head as a trophy.

The camels in the market each had a front leg tied back, to hobble them so that they could not wander off. The trader explained that some brokers were purchasing for the Egyptian market and others for the Gulf, where camel racing was very popular. He pointed to different dromedaries, extolling their virtues as he tried to gauge my interest. I asked if he had one that would carry me as far as London. ‘We have camels that go on land and sea,’ he enthused. ‘I have one that is a very good swimmer. I give you a very good price.’

I was not tempted to make an offer – not even for a moment.

*

Khartoum seemed a safe city and I was happy to walk on my own along its streets, which were apparently planned out using the design of the Union Jack.

Setting out to explore, I ambled down Nile Street, parallel to the Blue Nile River. I eyed the presidential palace in which Omar al-Bashir had installed himself after he came to power in a military coup in 1989. Despite his indictment by the International Criminal Court for war crimes and crimes against humanity for the deaths of over 300,000 in Darfur, Bashir remained firmly ensconced in power, winning presidential elections yet again in 2010.

Although they had since fallen out, Bashir’s key ally when he first came to power was the Islamist Hassan al-Turabi. It was Turabi who was credited with turning Sudan into an Islamic state – and a state sponsor of terror. In 1991, he established the Popular Arab and Islamic Congress, which attracted to its conference militants from across the world. At his invitation, Osama bin Laden took up residence in Khartoum, investing in local infrastructure and agriculture businesses – and in international terrorist networks. It was the 1998 bombings of US embassies in Tanzania and Kenya, killing 224 people, that marked the emergence of bin Laden and his al-Qaeda organization onto the world stage. In retaliation, President Bill Clinton ordered cruise missile strikes on the Shifa pharmaceutical factory in Khartoum (in the mistaken belief that it was making chemical weapons) and on al-Qaeda bases in Afghanistan, where bin Laden had relocated to.

I then spotted ‘Gaddafi’s Egg’, the conspicuous five-star Corinthia Hotel whose construction the Libyan leader had funded. At one stage, Gaddafi had sponsored the ‘Islamic Pan-African Legion’ as part of a scheme to unify Libya and Sudan. Gaddafi went through pan-Arab, pan-Islam and pan-African periods during his four-decade rule of Libya. He controlled the country through fear, protected by a nasty security apparatus. He assassinated those he did not like, supported rebels in different countries and allowed the Irish Republican Army and Palestinian militants to train in camps in Libya.

Gaddafi’s relations with the West deteriorated further after the 1988 bombing by Libyan officials of Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie, killing 270 people. However, following the invasion of Iraq in 2003, he feared he might suffer the same fate as Saddam and so gave up the nuclear capabilities he had purchased from A.Q. Khan, a Pakistani nuclear scientist. In response, international sanctions against him were lifted.

A little further down the road was the People’s Friendship Cooperation Hall, a massive structure that included a conference room, theatre and banquet facility. It was a gift from China, the largest investor in Sudan. China was building dams, railways, roads, power plants and pipelines, and it was Sudan’s biggest trade partner. The first China–Sudan oil deals were signed in 1995 and the main oil refinery was a joint venture between the two countries. Oil had long since replaced cotton as Sudan’s main commodity: 95 per cent of its exports were oil – sold mostly to China.

I took a raksha – a three-wheeled taxi – to Souq al-Arabi, a densely packed maze of stalls, carts and shops in the commercial heart of Khartoum, south of the Great Mosque. ‘Are you Chinese?’ the driver asked me. What a bizarre question, I thought. I do not look in the slightest bit Chinese. By way of explanation, the driver went on to tell me there were many Chinese working in Sudan.

Wandering through the Arab market, I passed the gamut of small businesses, all thronging with merchants and customers. Every imaginable item could be found in these stalls, from curtains to cement mix, table mats to musical instruments, spices to saucers, gauze to gold. I spotted a number of Chinese people. And lots of cheap Chinese produce.

*

Late in the afternoon on a Friday, I went back to Omdurman to visit the tomb of Hamed al-Nil, a nineteenth-century Sufi of the Qadiriyya order. Sufism, a mystical practice within Islam, had first come to Sudan in the sixteenth century. It was prevalent across the country, although rejected by fundamentalist Muslims.

The smell of incense was strong in the air. Around a hundred Sufis were gathered in a large circle, swaying back and forth, clapping their hands and reciting dhikr, the remembrance of Allah, accompanied by drums and cymbals.

‘La ilaha illa allah [There is no god but Allah],’ the dervishes chanted, dressed in green, with long dreadlocked hair and beads wrapped around their necks.

‘La ilaha illa allah,’ the crowd, in white, intoned back.

The dervishes whirled around and around, robes flowing and limbs swinging, chanting and spinning in a hypnotic display of religious devotion. After about an hour or so, the mystical Muslims, smiling in ecstasy, reached a state of trance.

The spectacle was mesmerizing. It was only when the evening call to prayer rang out that the spell was finally broken.

*

After a few days in Khartoum, I set out northwards by car along the road that Osama bin Laden had built in the 1990s, passing convoys of military vehicles, trucks and armoured personnel carriers.

It took half a day to make the 150-mile trip north-east to the Meroe pyramids. That night, I camped out in a tent. The desert was freezing. I climbed fully clothed into my sleeping bag, poking my head out of the flap of the tent to look at the glittering sky. Millions of stars shone brightly, and I could see them in their full glory without pollution or electric lights obscuring my vision. It took me a few seconds to locate the Pole Star and the Plough. As I gazed up at the galaxy, my world telescoped out. I realized, at that moment, that the Iraq War would assume a different perspective with the passage of time and distance. Despite the destruction and devastation that humans inflicted, the universe was so much bigger than us.

The cold kept me awake most of the night. I rose before dawn and climbed on top of a sandbank to watch the sun rise over the desert, turning the dunes a rusty orange. There was not a soul in sight as I wandered among the pyramids. They had narrow bases and steep sides, some about twenty feet tall, others rising to almost a hundred feet. They were smaller than the ones in Egypt but much more numerous – there were over two hundred of them, separated into three sprawling groups. Built between 720 and 300 BC as tombs for Nubian royals, they had weathered the test of time until an Italian explorer decapitated forty of them in the 1830s in search of treasure. Idiot.

Back on the road, I stopped at Musawarat, the largest Meroitic temple complex in Sudan, dating back to the third century BC. The caretaker approached me and asked me where I was from. When I told him, he responded: ‘Ah, Britain, you used to rule the world.’ He showed me around, pointing out the elephant training camp, college and hospital. As he noted that a certain artefact was missing, he looked me straight in the eye with one eyebrow raised. ‘It is in the British Museum,’ he announced.

I winced. This then became a running gag between us as we walked around.

‘This piece is missing,’ he would say, pointing to another empty space.

‘We’re keeping it safe for you in the British Museum,’ I responded with a grin.

He told me that his father had been the caretaker before him, and his grandfather before him. His family had lived there for generations.

Along the Nile between Aswan in Egypt and Khartoum, there are a few shallow stretches of river with white water, known as the cataracts. After leaving Musawarat, I stopped the car at the Sabaluqa Gorge, the sixth cataract. I lunched at a rudimentary restaurant on the riverbank, where fish was cooked over coals in front of me.

A boatman agreed, for a reasonable price, to take me out on his wooden vessel. It was painted blue and green, with a canopy that provided protection from the sun. I sat down towards the front on the wooden slats, while the boatman sat at the back next to the motor.

As we made our way through a granite canyon, I asked him if he had spent his whole life on this stretch of the river. Much to my surprise, he told me he had been a guest worker in Iraq for years, working in mortuaries. He remembered his time there fondly, and reminisced about the places he had visited: Najaf, Ramadi, Baghdad, Basra... He had been able to save money to send to his family back home, too. Iraq had been so modern, he told me, and he had loved it. He showed me photos of his sons, whom he had named Saddam, Qusay and Uday. Even his daughters were named after members of Saddam’s family!

‘Saddam was a good leader and did a lot for Iraq,’ he claimed, before lamenting how the Iraqi president had turned majnun (crazy) in later years, invading neighbouring countries and killing so many of his own countrymen. The boatman compared him to Colonel Gaddafi, who he said had started out as majnun but had recently become more normal.

I thought about Gaddafi’s meetings in his lavish Bedouin reception tent, his female bodyguards and the plastic surgery that had transformed his face. I was not sure at all that he had become less majnun.

*

Back in Khartoum, the British defence attaché, Colonel Chris Luckham, hosted me in the comfortable apartment he shared with two tortoises and his teenage son, who had tattooed on one arm ‘My name is Ozymandias, king of kings’. Chris and I had served together in Afghanistan in 2006. He had taken up his post in Khartoum in 2009 and was facilitating security negotiations between the government of Sudan and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement, in order to implement the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement to end the civil war that had caused the death of around two million people.

Chris was convinced that the problems of Sudan were resolvable. ‘It’s all about economics,’ he told me. ‘Sudan has potential: oil fields, the fertile Nile valley and Port Sudan, one of the five major access points to Africa. The challenge is the distribution of wealth – and migration to sustainable areas of Sudan.’

However, it seemed inevitable that north and south were headed towards separation. A referendum on the independence of the south was scheduled for 2011, vociferously supported by American evangelists, as well as film stars such as George Clooney.

On Remembrance Sunday, I accompanied Chris to the Commonwealth war cemetery in south-east Khartoum. Around two hundred people had gathered to pay tribute to the dead. It was a simple ceremony, held under bright blue skies. When it was over, I wandered the rows of immaculately kept graves, reading the names and dates from the two world wars. I reflected that while our soldiers continued to die overseas, these days their bodies were brought home – and not left buried in foreign fields.

On my last day in Sudan, Chris and I went out in his two-man kayak to where the White Nile meets the Blue Nile, the confluence known as al-Mogran. As we paddled, we kept close to the shores of Tuti Island, which supplies Khartoum with much of its fruit and greens. I had spent a day walking through the island’s citrus orchards and around its fields of vegetables. Now I was viewing it from a different angle.

Khartoum means ‘elephant trunk’ in Arabic, and it was apparently so named due to the shape of the river around Tuti Island. From the water, I could not tell where in the trunk we were. I was tired of paddling and my arms were aching. Chris admonished me to paddle harder, warning me that if I did not do so, we would not get back to shore in time and I would miss my flight.

‘Oh fuck,’ I responded, somewhat sarcastically. I would have been quite happy to stay longer.

But the trip had done the trick. Sudan had acted as a defibrillator, bringing me back to life and reviving my interest in the world.

*

In January 2011, I testified in London before the Chilcot Inquiry into the Iraq War. I sat on one side of the table facing the commissioners: Sir John Chilcot, a career diplomat and senior civil servant who chaired the inquiry; Baroness Usha Prashar, a member of the House of Lords; Sir Roderic Lyne, a former ambassador; and two historians, Sir Lawrence Freedman and Sir Martin Gilbert. I felt quite apprehensive. It was my first interaction with British officialdom since leaving Baghdad. But it also meant that, at last, someone wanted to hear my views on the situation in Iraq, what had happened and why things had gone so wrong.

At the end of the session, Sir Lawrence Freedman approached me and handed me his business card. He proposed that I come teach about Iraq at King’s College London where he was Professor of War Studies. But Harvard was in my sights by now. On my return from Khartoum, I had received notification that my application for a ‘spring semester’ fellowship was successful.

A few days after testifying, I touched down in the US at Boston Logan Airport. I stood in line at passport control and presented my British passport.

‘Ma’am, why were you in Sudan?’ the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) official inquired.

‘I went there on holiday,’ I responded.

‘Ma’am, nobody vacations in Sudan.’ He had already pressed a buzzer. Another humourless TSA official was quickly at the counter, instructing me to follow him. I was taken off to a special room to the side and told to sit. Mexicans, Muslims and me. Officials barked at us to remain silent and not to use our cell phones.

After thirty minutes or so, a security official returned with my passport. He leafed through the pages. ‘Ma’am, what were you doing in Sudan?’ he asked in a firm manner. I repeated that I had been on holiday. But he showed no interest in camel markets, whirling dervishes and Nubian pyramids.

He went on: ‘Ma’am, why were you in Eye-rak?’

‘I was working for the US military.’

‘Ma’am’ – his voice was now more aggressive – ‘you are British!’

Oh God. How was I going to explain how I had come to work for the US military? It was a long story.

The official was most unfriendly. My stamps from faraway places were not ones that the TSA coveted – they were setting off alarm bells. I wondered if he had ever set foot outside the United States.

I presented all my Harvard documentation and he went off with it, presumably to show it to one of his superiors. Did I really now fit the profile of a terrorist? I began to have serious concerns that I was going to be denied entry into the US.

An hour later, I was released. They had checked with Harvard and googled me. Yes, I had been accepted on a fellowship. Yes, I had indeed worked with the US military in Iraq.

As to why I had gone to the Sudan? That was something that, for them, was left unexplained.

*

Harvard was heaven. There were six of us selected to be resident fellows at the Institute of Politics at the John F. Kennedy School of Government; to be interesting people about campus in order to inspire students to pursue careers in public service. I ran a series of workshops on the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan under the banner ‘Post 9/11 wars – national security or imperial hubris?’ The discussions on whether the wars had made us safer or created more enemies appealed to a wide range of students: those in the military, Muslims, Republicans and Democrats alike. General Odierno, my former boss in Iraq, came to speak to the students prior to taking up his post as chief of staff of the US Army. General Petraeus Skyped into the class from Kabul, where he was commander of ISAF.

Students were assigned to help me organize my events and social life. Jimmy was chubby, long-haired and bearded before he became lean, cropped and clean-shaven; he had a girlfriend before he turned to boys. And Gavin was a football player, tall and chiselled and as straight as can be. Our last evening together, at the end of the semester in early May, we went to see the musical Hair in Boston, and rushed up on stage at the end to dance to ‘Aquarius/Let the Sunshine In’. It seemed a fitting send-off for Gavin, who signed up for the Marines the next day.

But while I was reliving student life in my forties in Cambridge, Massachusetts, great upheavals were taking place in the Middle East. In Tunisia, Mohamad Bouazizi’s self-immolation pushed President Ben Ali to flee the country. In Egypt, mass protests led to President Mubarak’s resignation and arrest. In Yemen, there were large-scale demonstrations calling for Ali Saleh to step down. In Libya, Gaddafi threatened to hunt people alley by alley – zenga zenga – which led to a UN Security Council resolution authorizing a no-fly zone over the country and ‘all necessary measures’ to protect civilians. In Bahrain, protestors gathered at the Pearl Roundabout. In Syria, thousands congregated in Damascus, Aleppo, Homs and Hama.

Across the Middle East, young people were going onto the streets to demand dignity and justice. They seemed to be speaking with one voice – in unity across the Arab world – angered at regimes that did little for their people and treated public goods as private possessions. Arabs were no longer saying they were hapless victims and that the West was to blame for all the ills afflicting their region. They were mobilizing – and using the Internet and social media to great effect. Dictators were fleeing in the face of popular protests rather than foreign intervention. The wall of fear was coming down, and at long last, positive changes appeared to be on the horizon for the Middle East, generated from inside the countries themselves.

A huge drama was playing out. And, even in the United States, I felt caught up in it. I followed it obsessively on the Internet and on TV, and posted incessantly about it on Facebook.

I yearned to experience the energy and camaraderie of the revolutions. And I wanted to find out whether democracy was really coming to the Middle East – and what influence, if any, the Iraq War had had on the region.

I decided to travel the Arab Spring.

CHAPTER 1

Hold your head up, you’re an Egyptian!

Egypt

May 2011

‘Ash-sha’b yurid isqat an-nizam!’ the Egyptians chanted over and over again.

I joined in with them, cautiously at first and then more enthusiastically. ‘Ash-sha’b yurid isqat an-nizam! [The people want the fall of the regime!]’ There was something so rebellious, so enrapturing, so empowering in those words. It was intoxicating.

It was May 2011, and although President Mubarak had been removed three months previously, Friday demonstrations had turned into a weekly ritual. Egyptians waved flags, their hands and faces painted in its colours of red, white and black. I read the slogans on the banners: ‘Bread, freedom and social justice’, ‘Muslims and Christians – we are all Egyptians’, ‘The army and the people are one hand’.

In the circle in Cairo’s Tahrir Square that day, protesters were angered by rumours that Mubarak was being offered amnesty on the condition that he returned the money he had taken and also apologized to the Egyptian people. They scoffed that his wife, Suzanne Mubarak, had only admitted to assets worth $4 million, and they demanded she be jailed. There were posters depicting Mubarak trying to run off with the wealth of the Egyptian people; on another, Zakaria Azmi, his chief of staff, was portrayed as a tortoise and accused of ‘Corruption, blood and slow governance’; yet more showed the entire Cabinet with vampire teeth.

Further details of the dishonesty of the old regime were coming to light. The former tourism and housing ministers were both in jail awaiting trial, accused of selling off plots of prime real estate for virtually nothing to their cronies, who then made millions. Businessmen close to the regime had received government contracts and loans, while most Egyptians had few economic opportunities.

A man, who I presumed from his beard was one of the Ikhwan, the Muslim Brotherhood, led the crowd in chants. Everyone joined in. Then it was the turn of a young cleanshaven man, who chanted the revolutionary slogan ‘Hold your head up, you’re an Egyptian’.

I moved towards another area. A young woman, wearing a baseball cap and a black-and-white chequered keffiyeh scarf around her neck, stood on a platform singing before a group of female activists. There had been reports of horrible sexual assaults in Tahrir Square, but this woman stood boldly in front of the crowd. She shrieked the lyrics, inviting her audience to shout back. Her confidence was extraordinary. What she lacked in musical talent, she made up for in enthusiasm.

I looked around me. Mubarak’s National Democratic Party building had been gutted by fire. Guards now appeared to be protecting the red neoclassical Egyptian Museum, repository of some of the finest ancient treasures in the world. It had been broken into on 28 January 2011 – the ‘Day of Rage’ – with some of the displays damaged and artefacts looted. The fourteen-storey Mogamma building, which housed myriad government agencies, had been left untouched. I hated that place. As a student, I had once queued there for hours and hours, waiting for a permit to visit the Western Desert oases. A 1992 Egyptian movie Al-irhab wal kabab (The Thief and the Kebab) tells the story of a man who takes people in the Mogamma building hostage after trying unsuccessfully for weeks to complete paperwork. Everyone wants to know about the big political statement he’s making, but there is none. He was simply hungry and wanted a kebab - and justice. I found it odd that this building had been spared. Perhaps it was because so many Egyptians were on the public-sector payroll.

I struck up conversation with the man standing next to me. ‘The situation is much better since the revolution,’ he told me. ‘There is more freedom. No police knocking on doors in the night and taking people away.’

After years of passive compliance, the Egyptian people were no longer accepting their lot in life. It was they – not Western intervention – who had removed an autocratic regime. The power of the people.

Egypt, Umm al-Dunya (Mother of the World), was once more leading the region. New identities were being created. New friendships were being formed. In Tahrir Square, people helped each other: they collected the trash, they provided drinks, they administered first aid. I had never witnessed such a spirit in all the years that I had been visiting Egypt. They were fearless in their demands for dignity. And my heart was with them.

*

The British ambassador, Dominic Asquith, had kindly offered to host me during my stay in Cairo, after I emailed him asking if he might have time to meet. It was his last month in Egypt, and he was packing up.

I had first got to know Dominic in Baghdad in 2004, when we both lived in ‘Ocean Cliffs’, the name ironically bestowed on the trailer accommodation in an underground car park that protected us from incoming rockets. The great-grandson of British prime minister H.H. Asquith, Dominic certainly looked more at home in the substantial stone building in Cairo than a containerized housing unit in Baghdad.

Built in 1894, the ambassador’s residence served as a reminder of Britain’s former prestige and power. It was here that General Kitchener planned the expedition to the Sudan to avenge General Gordon’s death. In fact, Dominic’s desk was the very one he used. The bedroom assigned to me was where Churchill used to stay during his visits. It was larger than my whole house in London. And when I opened the shutters, I looked out upon the Nile.

Over dinner and wine, Dominic explained the events that had led to the revolution. Khaled Said, a young middle-class man with an interest in computing, had been arrested in a cybercafé in Alexandria by two detectives on 6 June 2010. They smashed his head against a door, beat him to death and stuffed drugs down his throat. Photos of the battered body went viral. Dominic said that Egyptians had been furious that the police would no doubt escape with impunity. He pointed out that if such an end could come to an innocent-looking kid from Alexandria, then no Egyptian felt safe.