11,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

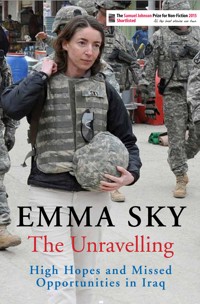

SHORTLISTED FOR THE ORWELL PRIZE 2016 SHORTLISTED FOR THE SAMUEL JOHNSON PRIZE 2015 Emma Sky was working for the British Council during the invasion of Iraq, when the ad went around calling for volunteers. Appalled at what she saw as a wrongful war, she signed up, expecting to be gone for months. Instead, her time in Iraq spanned a decade, and became a personal odyssey so unlikely that it could be a work of fiction. Quickly made civilian representative of the CPA in Kirkuk, and then political advisor to General Odierno, Sky became valued for her outspoken voice and the unique perspective she offered as an outsider. In her intimate, clear-eyed memoir of her time in Iraq, a young British woman among the men of the US military, Emma Sky provides a vivid portrait of this most controversial of interventions, exploring how and why the Iraq project failed.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

THE

UNRAVELLING

First published in hardback in the United States in 2015 by PublicAffairs™, a Member of the Perseus Books Group.

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2015 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Emma Sky 2015

The moral right of Emma Sky to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Extract from ‘Out of the East’ by James Fenton taken from Yellow Tulips: Poems 1968–2011

© James Fenton and reprinted by permission of Faber and Faber Ltd

‘Iraq’ reprinted courtesy of Adnan al-Sayegh

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-78239-257-6

E-book ISBN: 978-1-78239-259-0

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-78239-260-6

Printed in Great Britain

Book design by Jane Raese

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

TO

GENERAL RAYMOND T. ODIERNO

AND ALL THOSE WHO SERVED IN IRAQ

DURING THE AMERICAN ERA

AND

TO MY IRAQI FRIENDS

CONTENTS

List of Abbreviations

Preface

Maps

Prologue: The Iraq Inquiry

PART I

DIRECT RULE

JUNE 2003–JUNE 2004

1

To the Land of Two Rivers

2

Sky Soldiers

3

“Our Miss Bell”

4

Scramble for Kirkuk

5

Life in the Republican Palace

6

The Assassination of Sheikh Agar

7

Goodbye to All That

PART II

SURGE

JANUARY–DECEMBER 2007

8

Back to Baghdad

9

Fard al-Qanun

10

Awakening to Reconciliation

11

Surging through the Summer

12

Sadrist Ceasefire

13

Victory

PART III

DRAWDOWN

MAY 2008–SEPTEMBER 2010

14

Melian Dialogue

15

Uncomfortable SOFA

16

Out of the Cities

17

Trouble along the Green Line

18

Election Shenanigans

19

Losing Iraq

PART IV

AFTERMATH

JANUARY 2012–JULY 2014

20

Things Fall Apart

Glossary: Political Parties and Militias

Acknowledgments

Index

About the Author

ABBREVIATIONS

AFN

American Forces Network

AQI

al-Qaeda in Iraq

BOC

Baghdad Operations Command

BUA

Battle Update Assessment

BUB

Battle Update Brief

CHOPS

Chief of Operations

CLC

Concerned Local Citizens

COIN

counter-insurgency

CPA

Coalition Provisional Authority

DFAC

dining facility

DFID

Department for International Development

EFP

explosively formed projectile

FCO

Foreign and Commonwealth Office

FOB

Forward Operating Base

FRAGO

fragmentary order

GOI

government of Iraq

IED

improvised explosive device

ISAF

International Security Assistance Forces

ISF

Iraqi security forces

JAM

Jaysh al-Mahdi

JOC

Joint Operations Command

KIA

killed in action

KDP

Kurdistan Democratic Party

KRG

Kurdistan Regional Government

MNF-I

Multi-National Force—Iraq

NGO

non-governmental organization

OCINC

Office of the Commander-in-Chief

POLAD

political adviser

PRT

Provisional Reconstruction Team

PUK

Patriotic Union of Kurdistan

RAF

Royal Air Force

RPG

rocket-propelled grenade

SOFA

Status of Forces Agreement

TAL

Transitional Administrative Law

TOC

Tactical Operations Center

UNAMI

United Nations Assistance Mission for Iraq

USAID

United States Agency for International Development

WIA

wounded in action

WMD

weapons of mass destruction

PREFACE

NOTHING THAT HAPPENED in Iraq after the overthrow of Saddam Hussein in 2003 was preordained. And there was nothing inevitable about the way the story unfolded.

This memoir recounts my experiences in Iraq over more than a decade. My story starts when I responded to the British government’s request for volunteers to help rebuild the country after the fall of the regime and found myself responsible for Kirkuk, trying to diffuse tensions between the different Iraqis scrambling to control the province. It continues through the Surge when I served as the political adviser to General Ray Odierno; goes through the drawdown of US troops; and ends with the takeover of a third of Iraq by the Islamic State. It is a tale of unintended consequences, both of President Bush’s efforts to impose democracy and of President Obama’s detachment; of action as well as non-action.

The Unravelling describes the challenges of nation building and how the overthrow of an authoritarian regime can lead to state collapse and conflict. It reminds us of the limitations of external actors in foreign lands, but also where we can have influence. Those the US-led Coalition excluded from power sought to undermine the new order that was introduced. And those we empowered sought to use the country’s resources for their own interests, to subvert the nascent democratic institutions, and to use the security forces we trained and equipped to intimidate their rivals. There was more the US could have done to help broker a deal among the elites and to ensure the peaceful transfer of power through elections. Instead, the US took the risky gamble of betting on Nuri al-Maliki, in the mistaken belief that he shared the same interests and goals as us, and that he would use the dramatic decline in violence brought about during the Surge to build up a “sovereign, self-reliant and democratic Iraq.” The failure of this policy became only too apparent when the Islamic State (Da’ash) catapulted to prominence in June 2014, taking control of vast swathes of Iraqi territory and presenting itself as the defender of Sunnis against the Iranian-backed Shia-led regime in Baghdad; and when the Iraqi Security Forces deserted and dissolved.

PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA became the fourth American president to order airstrikes on Iraq, following in the footsteps of George H. W. Bush, Bill Clinton and George W. Bush. The initial airstrikes were to stop Da’ash from exterminating Iraq’s minorities and taking over Erbil. However, following the beheadings of two American hostages by Da’ash, the US quickly expanded its airstrikes into Syria. Americans were no longer war weary. They were scared again—and wanted retribution.

Never had Obama expected to find himself in such a position. He had campaigned for president pledging to end the Iraq war. In 2009, still in his first year in office, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his “extraordinary efforts to strengthen international diplomacy and cooperation between peoples.”

Obama, who had presented himself as the president who would extract America from its foreign entanglements and focus on nation building at home, has reluctantly taken the country back to war in the Middle East—with no sense of how it will end.

Da’ash is the hideous product of a sacralised determinism born out of secular failure. The dramatic changes in the regional balance of power in Iran’s favour (brought about not least by the Iraq war) and the deep social, economic and political problems in the Arab world (which sparked the “Arab Spring”) have convinced some Sunnis that we live in an ungodly age of political injustice where suffering, terror and armed conflict are the true tests of righteousness—and will be rewarded. Others simply want revenge for what they see as Iranian triumphalism and Sunni humiliation. Regional actors—state and non-state—have sought to project their influence and mobilise the faithful by supporting sectarian actors in different countries. And many Arab governments remain incapable of responding to the demands of their increasingly young and inter-connected populations. Da’ash feeds on a Sunni sense of disenfranchisement and grievance and claims to offer a better future in the form of an idealised past—an unmoored, postmodern Caliphate with globalised ambitions and a new territorial base. The rise of Da’ash (the successor to al-Qaeda in Iraq) and the sectarianisation of conflict in the region are symptoms of highly complex and intractable pathologies in the Middle East. They show that ideas matter. But if the very conditions that gave rise to Da’ash are not addressed, then its ideology will continue to attract adherents, and it will likely be succeeded some time in the future by son-of-Da’ash. And the cycle will continue.

The Unravelling is essentially the story of women and men, of Iraqis and Americans, of soldiers and civilians, ordinary and yet extraordinary, whose lives became so entwined in “the land between the two rivers.” It is a story I have chosen to share to honour the efforts of those who strived, to remember the lives that were lost, and to pay tribute to a broken country that I came so much to love.

The Iraq war and its outcome affected few Americans. There is little willingness to really reflect on or take responsibility for what happened there. The legitimacy of the war was disputed right from the outset. Iraqis blame the US for destroying their country; and Americans blame Iraqis for not making use of the opportunity given to them. Politicians try to use the situation in Iraq for political advantage, without much consideration of Iraqis themselves: Democrats blame Republicans for invading Iraq in the first place and Republicans blame Democrats for not leaving troops there. The US military blames US government civilians for not doing enough; and the latter blames the former for trying to do too much. Brits blame Tony Blair.

But what happened in Iraq matters terribly to Iraqis who hoped so much for a better future, and to those of us who served there year after year. If we refuse to honestly examine what took place there, we will miss the opportunity to better understand when and how to respond to instability in the world.

Iraq

by Adnan al-Sayegh

translated by Soheil Najm

Iraq that is going away

With every step its exiles take. . . .

Iraq that shivers

Whenever a shadow passes.

I see a gun’s muzzle before me,

Or an abyss.

Iraq that we miss:

Half of its history, songs and perfume

And the other half is tyrants.

PROLOGUE

THE IRAQ INQUIRY

14 JANUARY 2011. It was a chilly morning. I got off the number 87 bus at the Houses of Parliament and walked past Westminster Abbey, turning left down Great Smith Street. I was dressed in a suit for the first time in years. I had an appointment to appear before the Iraq Inquiry (also known as the Chilcot Inquiry). It was not a war crimes tribunal. No official in the UK—or US—would ever be held accountable for the decision to go to war in 2003 or the way in which the post-war phase was implemented. But it was an investigation into what had happened, in order to draw lessons for the future. Hundreds of officials had already given their testimony since the Inquiry was established in mid-2009. Now it was my turn.

I entered a nondescript building. An official appeared, handed me a badge and showed me to the room. I was introduced to the commissioners: Sir John Chilcot, a career diplomat and senior civil servant who chaired the Inquiry; Baroness Usha Prashar, a member of the House of Lords; Sir Roderic Lyne, a former ambassador; and two historians, Sir Lawrence Freedman and Sir Martin Gilbert. I took my seat on one side of the table, facing my interrogators. I felt slightly apprehensive, but I kept telling myself that nothing could faze me after my Iraq experience. No one was going to die.

BARONESS PRASHAR: Can we start with some background information first? Can you describe how you were recruited to work for the CPA [Coalition Provisional Authority]?

EMMA SKY: There was an e-mail that was sent around the Civil Service asking for people to volunteer to go and work for the CPA. It was going to be Brits and Americans administering the country. I wasn’t in the Civil Service. I was in the British Council. The e-mail was forwarded to me. I expressed interest and became a secondee to the FCO [Foreign and Commonwealth Office] and then on to the CPA.

BARONESS PRASHAR: And what briefing were you given before you went to Iraq?

EMMA SKY: I was not given a briefing. There was a phone call. It basically said, you know, you’ve spent a lot of time in the Middle East. You will be fine. Turn up at RAF Brize Norton. As soon as you get to Basra, there will be somebody to meet you . . . They will be standing there with a sign with your name on it and they will take you to the nearest hotel . . .

BARONESS PRASHAR: But apart from a phone call were you given any information about the Security Council Resolution 1483 and its implications for serving in the CPA?

EMMA SKY: I don’t recall receiving any.

BARONESS PRASHAR: It would be helpful if you can just describe what your role and responsibilities were during your period at the CPA.

EMMA SKY: The CPA looked at the country as . . . fifteen provinces plus Kurdistan. So in each of the fifteen provinces they had a senior civilian, who was known as the governorate coordinator, and assumed the role a governor would play . . . responsible for the administration of the province, working with the US military, working with Iraqis, finding local leaders, working out who could take what responsibilities, building up their capacity to govern the province themselves.

BARONESS PRASHAR: And what were your specific responsibilities? What were you tasked to do?

EMMA SKY: There was no job description. We weren’t given outlines of what our jobs were . . . I don’t recall receiving an outline of what my job was until maybe September. So up until then it was really how I interpreted what my role should be . . .

SIR RODERIC LYNE: I just wonder if I can come back to the beginning of this conversation just to make sure I’ve really understood it. When you went out there, you say you had no written briefing, no terms of reference, no instructions and you did not have any oral briefing from anybody other than to turn up at Brize Norton and fly out to Basra?

EMMA SKY: No.

SIR RODERIC LYNE: Nothing at all?

EMMA SKY: No, not before I left the UK. I don’t recall any at all except the one phone call. When I got to Basra, obviously there was no one there with a sign with my name on it—nor a hotel. So I went on to Baghdad. I made my way to the Palace and there I met the British team . . . I spent a week going round the Palace seeing how things worked, getting as many briefings as I could. They said: we have enough people here. We don’t have enough people in the north. Go north. So I went to Mosul. They said: we’ve got someone here. I went to Erbil. They said: we’ve got someone here but we haven’t got anyone in Kirkuk. So I went to Kirkuk. I didn’t know I was going to Kirkuk when I left the UK.

SIR RODERIC LYNE: So when you left the UK, you didn’t know where you were going. You presumably didn’t even know what kind of clothes to put in your suitcase?

EMMA SKY: Well, no. I was only going for three months.

THREE HOURS AFTER it had begun, the interrogation wound to a close. I looked towards Sir John Chilcot, hoping for some words of reassurance, willing him to recognize that despite the impossible challenge, I had tried my hardest in very difficult circumstances.

Judging from Sir John’s face, he was reeling from what I had told him. I had been opposed to the war and naturally suspicious of the military. Yet I had volunteered for three months to help get Iraq back on its feet—and within weeks of the fall of Saddam I had found myself governing a province. By the time I left Iraq many years later, I had served as the political adviser to American generals through the surge and the drawdown of US troops. A British woman, advising the top leadership of the US military . . . I suppose it must have seemed an unlikely story.

PART I

DIRECT RULE

JUNE 2003–JUNE 2004

1

TO THE LAND OF TWO RIVERS

All we are saying is give peace a chance.

—JOHN LENNON

IT WAS MID-MORNING on Friday 20 June 2003. At the RAF base at Brize Norton, west of London, I stood waiting for the flight to Basra with two hundred or so British soldiers. I was struck by how young and innocent they looked. Some were still pimply teenagers in clean and starched uniforms. Huddled together in their groups, a few stared at me, but most blanked me as if I did not exist. I felt quite out of place. I had never flown on a military plane before and did not have a ticket. However, I was pleased to discover that my name was on some register and that was all that mattered. I gave my rank as “civilian,” checked in my bag and boarded.

It was certainly a no-frills airline, with no seats assigned. During the flight, a soldier handed out packed lunches. I grabbed one, and quickly ate the stale sandwich and chocolate bar. I tried to sleep, but I was both excited and apprehensive. I was being seconded to the Foreign and Commonwealth Office to help administer Iraq for a couple of months while the country got back on its feet. I was confident that the FCO knew what it was doing. I had just not yet been informed. The invasion had occurred three months previously and the war was supposedly over. I was not unduly worried.

At Basra International Airport I wandered into the terminal and sat waiting for my bag. I looked around the airport, taking in the once grandiose and ornate interior, now damaged by war, looting and neglect. Military Bergen rucksacks and guns wrapped up in canvas came round on the carousel. And then, a little incongruously, my bright-purple backpack. I lifted it onto my back and headed off in search of Customs. But there were none. No stamping of the passport. No entry visa. No Iraqis.

I had been told that someone would be waiting for me, placard in hand. But nobody was. It didn’t take me long to realize that no one was expecting me. The place was swarming with British soldiers who seemed to know where they were going. I went upstairs to where “transit passengers” were accommodated. It was the corridor from hell: 120°F, no windows, no fans, no air conditioning and florescent lighting which stayed on all night thanks to a generator. All along the corridor male soldiers lay on cots and mats, stripped down to their underwear. I did not think that was an option for me. Nor did I have a sleeping mat. I stretched my towel out on the concrete and lay down on top of that. Some of the soldiers were already snoring away, but I got little sleep.

In the morning I lined up for the Porta-Johns, went to the communal shower (which had no water) and sat down to eat breakfast. My first meal in Iraq was a “Meal Ready to Eat,” US military rations that British soldiers had “acquired” to break up the monotony of their own. I followed the instructions carefully: open packet; take out contents; fill bag with cold water up to the level mark; put back silver packet; fold bag at top and wait. Sure enough the bag began to heat up, cooking the contents of the silver packet. And within ten minutes I was tucking into tortellini. Not the first breakfast I expected to eat in Iraq, but I was starving.

I decided to head for Baghdad, in the hope that someone there was expecting me and had a job for me to do. I hitched a lift on an RAF C-130 Hercules. For a civilian, this was an experience in itself. Military flights were basic. There was no protection from the temperature or the noise. I strapped myself into one of the seats that ran alongside the frame of the plane and hung my arms through the red meshing behind me, keeping my limbs away from my body in an attempt to cope with the heat. I listened intently to the safety instructions barked out by one of the RAF crew, pointing at the different doors: “If we crash into the sea, you go out that exit. If we crash on land, you go out this exit.” I really thought we crashing when the plane descended rapidly in a spiral. The pull of gravity left my whole body feeling it was being violently compressed. I was later told that this was a “corkscrew landing” to avoid being hit by missiles.

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!

Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!