11,51 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Fernhurst Books Limited

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

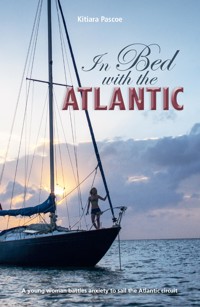

In Bed with the Atlantic is a travel memoir of a young woman, Kitiara Pascoe, as she goes from never having stepped on a yacht, to sailing over 18,000 miles – across the Atlantic, around the Caribbean and then back – in three years with her partner. At first, she was dogged by doubt, a belief that she wasn't a 'sailor', never would be and that she was in no way capable of such an undertaking. She believed that the ocean was out to get her, that weather needed to be battled with and that she would forever be ruled by anxieties that plagued her. Woven into the narrative of the journey's progression are stories from Kit's childhood and life before the voyage, explaining her battles with anxiety and the feelings of being lost as a graduate in post-recession Britain. The book also relays her struggle with reconciling a life of travel with the expectations and experiences of those back home, at an age when most of her contemporaries were starting corporate careers and families. In her courage to leave everything she knows behind, she learns the history of the islands and their people, swims with turtles, explores strange cave systems, and learns to forage for food straight from the sea. But she also encounters hardships like running out of food and water, battling against storms, trying not to be struck by lightning, and discovering the crippling loneliness of sailing an ocean for months on end. Sailing back to the UK after three years Kit realises the colossal difference that sailing has made to her life and understanding of the world. She ponders how easy it is not to do something, to protect ourselves from risks and ridicule and everything that makes us uncomfortable. But now appreciates that it is only when we take the risk, that we get the reward and that we connect not just with the world at large, but also with ourselves.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

For Berwick Maid and herwonderful captain Alex

Contents

List of stop-overs

Chapter 1

I Bought A Boat

Map

Europe: Out

Chapter 2

Spanish Horizons

Chapter 3

A Secret Island

Chapter 4

A Familiar Ocean

Chapter 5

Full Sea

Map

Caribbean

Chapter 6

Racing Grenada

Chapter 7

Tropical France

Map

Caribbean Sea

Chapter 8

Caribbean Crossing

Chapter 9

Sloth Hunting

Chapter 10

Beating Through Rainbows To Paradise

Map

Bahamas

Chapter 11

The Sky, The Sea And The Wind

Chapter 12

Northern Bahamas

Chapter 13

Riding The Gulf Stream Home

Map

Europe: Home

Chapter 14

The Outpost Island

Chapter 15

A Circle Has No End

Chapter 16

The Final Stretch

Sources

Glossary of Nautical Terms

List of stop-overs

EUROPE

England

Southampton

Dartmouth

Salcombe

Mullion Cove

Helford River

Falmouth

Spain

A Coruña

Ares

Laxe

Camarinas

Muros

Bornalle

Ribeira

Pobra do Caraminal

Baiona

Portugal

Povoa de Varzim

Porto Santo

Vila Baleira

Madeira

Canical

Canary Islands

Lanzarote

Arrecife

Playa Blanca

Graciosa

Playa La Francesa

Fuerteventura

Gran Tarajal

Tenerife

Santa Cruz

La Gomera

San Sebastian

Gran Canaria

Las Palmas

CARIBBEAN

Grenada

Prickly Bay

St George’s

Dragon Bay

Carriacou

Tyrell Bay

Hilsborough

St Vincent and the Grenadines

Union Island

Clifton

Frigate Island

Mayreau

Tobago Cays

Canuoan

Bequia

St Vincent

Saline Bay

Petit Rameau

Tamarind Beach

Port Elizabeth

Wallilabou Bay

St Lucia

Martinique

Rodney Bay

Fort-de-France

L’Anse Martin

Sainte-Anne

Le Marin

Le Robert

St Pierre

Guadeloupe

Antigua

Deshaies

Falmouth Harbour

St Martin

Marigot

CENTRAL AMERICA

Panama

Bocas del Toro

Red Frog Marina

Colombia

Isla Providencia

NORTH AMERICA

Bahamas

Great Inagua

Mayaguana

Long Island

Great Exuma

Matthew Town

Abrahams Bay

Clarence Town

George Town

Elizabeth Island

Exumas

Rat Cay

Lee Stocking Island

Norman’s Pond Cay

Rudder Cut Cay

Great Guana Cay

Staniel Cay

Pig Beach

Cat Island

The Bight Settlement

Eleuthera

Rock Sound

Great Abaco

Marsh Harbour

Man-O-War Cay

Elbow Cay

Great Exuma

George Town

Rum Cay

Nesbitt Point

EUROPE

Azores

Flores

Lajes das Flores

Sao Jorge

Velas

Terceira

Praia da Vitoria

Spain

Punta de Sardineiro, Finisterre

Muxia

A Coruña

Sada

France

Kerdivizian

(Brest Estuary)

England

Dartmouth

Studland

Newtown

Southampton

Chapter 1

I Bought A Boat

I’ll never know, and neither will you, of the life you don’t choose.

Cheryl Strayed

“I would hope that we won’t capsize but, if we do, you need to grab Freddy and swim out from underneath,” said my dad as we sat huddled in the Wayfarer.

I looked at my stepbrother, he was eight, I was sixteen. He didn’t look as concerned about this as I was. I hoped that sisterly instinct would kick in should we be plunged into the Solent’s chilly May water and that I’d focus more on saving his life than panicking about my own. I eyed up the Lymington to Yarmouth ferry as it trundled past in a mess of wash and prayed we’d never have to find out.

I don’t remember much of that sail except for the tension that filled my body as we spent a freezing hour avoiding gigantic ferries and seeing my discomfort mirrored in the face of my stepmother. We didn’t capsize and instead retired quickly to the yacht club where I could focus on more important things like catching the eye of the barman who’d been a few years ahead of me in school.

I’d never really been on a boat before that day, with the exception of the town-sized cross-Channel ferries to mainland Europe, and I had absolutely no intention of repeating the experience. I made sure I was always working when it looked like my dad might remember he had a dinghy and generally steered clear of any activity that would involve getting into the steel grey Atlantic.

Despite my reticence about the sea, I never lived far from it and was brought up a mere mile or two from the Solent’s busy shores. When it came to choosing a university I knew I couldn’t bear to be inland, I needed to be able to walk to the sea, I needed it near me.

I eventually studied in Plymouth, a seafaring city only second to the twins of Southampton and Portsmouth. The sea wasn’t just in my vicinity though – it was in my blood.

My grandfather was a naval architect in Southampton for decades and retired when the company moved to Portsmouth; he still sails in the Solent. His brother, my great uncle is Dick Holness, the author of the East Coast Pilot who spends his free time happily sailing Kent waters. But the connection goes further: just a couple of generations back on my family tree was Ernest Holness, the stoker onboard Shackleton’s extraordinary and ill-fated 1914 expedition to the South Pole.

Even my mother spent her childhood messing about in the family dinghy and did I mention my father was in the Navy? Considering Britain has cold and temperamental waters, it surprised me that anyone learns to sail there, let alone numerous members of my own family.

I was quite happy having missed the family sailing gene, happy to spend my time outdoors rock climbing, ambling up mountains and cycling in the flat and friendly New Forest. I didn’t know that the world was plotting something behind my back; blood is thicker than water they say, well I didn’t stand a chance when my blood was water. Seawater.

It wasn’t until 2013 that my fate was sealed and I found myself with a boat. I’d picked up Alex at a party in Plymouth quite accidentally in 2011. He was dressed as a pirate and I was dressed as a cabin boy complete with eyeliner moustache; tied around his waist was the same British ensign that we would fly three years later all the way to Central America.

Together we returned to the Solent, where he’d grown up too, except that he hadn’t avoided sailing as deftly as I had. In fact, he’d grown up sailing on board his parents’ Moody 34, Isabella.

He had come to the same conclusion though that I had on that cold day in the Wayfarer; sailing in England was simply too grey, too wet and too cold. Still, after crewing on a tall ship from New Zealand to Fiji, he knew what sailing could be like.

“I bought a boat,” he said as I shut the car door against the February wind. I looked at him.

“Actually?’

“Actually,” he said with a grin.

We had discussed the buying of the boat but, at the time, I was living in Exeter for work and he had been viewing yachts alone. It seemed far away and disconnected and, to be honest, I really hadn’t taken it very seriously.

We’d spent many conversations in the last two years talking about sailing around the world, or, after looking at the size of the Pacific, sailing to the Caribbean. The idea of sailing around tropical islands appealed to me and it wasn’t like you could backpack through the Caribbean very easily.

I’d read as many sailing accounts as I could find, amazed at how many of them had been sitting in my dad’s bookshelves for all those years, waiting for me. While the conditions at sea in all those books sounded terrifying for someone who still believed yachts naturally wanted to be upside down, the theme of exploration and freedom pierced through those pages with such force that I soon became convinced.

Life got in the way though: masters degrees, office jobs and the millions of other tiny things that hook you into the ground and make you think you can’t leave. But two years after we’d met we were in the same position, bored and ill contented. We didn’t want to buy a house, we didn’t want to work for other people and we didn’t want to stay in one place. But we didn’t want to backpack either, finding hostels, waiting for buses and stuffing our lives into bags every few days.

We were waved past by security in a disused power station and the huge neglected chimney, that Solent sailors had used for decades as navigation, stood cold and empty above us. The weather-beaten warehouses and sprawling outbuildings sat upon vast pipes that lead to the nearby oil refinery and in hidden tunnels across the water.

An abandoned icon in Southampton’s history, Fawley was now in stasis, a shadow of the once thriving industry that brought thousands of workers and their families here in the 70s. With a workforce of just a handful of security guards, the power station’s unique yacht club had been put on notice. The boats of the long retired workers needed to be gone.

The car crunched over icy gravel and I saw the boat on crumbling concrete, propped upright by planks of wood, her full keel patchy with red paint. She looked sad, cold and alone. I still knew very little about yachts and she struck me as tiny and old, nothing like the white, luxurious creatures that the term ‘yacht’ had always brought to my mind.

I got out of the car with great reticence. It was, unbelievably, snowing very lightly, a phenomenon almost unknown in Southampton. It was one of the coldest Februaries I had ever known and it didn’t exactly shine a light on my first impressions of our new yacht.

With white, numb hands I climbed the ladder and found myself in the cockpit of this 1974 Nicholson 32 Mark X. I didn’t know what to do. I sat on a moulding, peeling cockpit locker lid and grimaced unintentionally at my surroundings.

There was algae and mildew everywhere, the once-off-white vinyl inside had long since slipped onto another Dulux colour chart and a gimballed microwave sat forlornly on its studs. The whole boat smelt of damp, homesick teak.

I suppose I was mainly surprised about the size of the interior. With a beam of only 2.8 m at the widest part, the inside consisted of a narrow saloon, a tiny bathroom and long forepeak, open all the way to the very bow. Three ‘rooms’. That was it. My confidence had been dulled and I simply couldn’t imagine living aboard. There was nothing inside but dust, nothing to make it look like a home.

And yet, as I stood in ski socks and four layers of clothing in the middle of the saloon floor, a tremor of excitement tapped out a melody on my bones. Like a newlywed couple with the blueprints of the house they’d build, I felt as though something was starting here, something

with a force all of its own.

Within weeks it was clear that living three hours apart was simply not working and so I handed my resignation in at my office and began working my month’s notice.

I wasn’t exactly shouting our pelagic plans from the rooftops but I was close to the colleagues in my team and they were aware that I planned to sail to the tropics.

One of the more irritating aspects of my job was to collect paperwork and cheques from the accounts department and deliver them to the desks of the lawyers they belonged to. It was in these instances, three times a day, that I could really see the thousands I’d spent on university tuition paying off. I still thought then that a piece of paper somehow made me more deserving of respect.

I leafed through a small mountain of papers slumped over my arm and extracted a handful to pass to a lawyer not on my team but situated a few desks over. At that moment a secretary I worked closely with bustled over with something for him to sign.

I don’t use the term ‘bustled’ as a cliché, she literally did bustle, she was a bustler. She was also the kind of person you’d describe as having a ‘heart of gold’ and was the most shocked by my ocean-going ambitions.

“Did you hear Kit’s going to sail to Australia?” she said to the lawyer as he scrawled on a dotted line. He sniggered.

“Seriously?” he asked me.

“Well not Australia necessarily but hopefully to the Caribbean,” I said, my stomach tightening.

He looked at me and laughed a short, ugly laugh, “I bet you haven’t even sailed across the Channel,” he said.

I felt liked I’d been slapped across the face; the derision that sat heavy in his words was not only unexpected but downright rude from someone I considered only one degree short of being a stranger.

But mainly I felt humiliated because he was right. I raised an eyebrow and returned to my desk as though I considered it so obvious I’d sailed across the Channel that I didn’t feel it necessary to defend myself. I stared at my screen and the text swam in front of my eyes. Is that what everyone thought of me? That I was just some naïve 20-something with big, stupid dreams?

I hadn’t ‘even’ sailed across the Channel; I hadn’t sailed at all. I hadn’t exactly made this known because I didn’t want to be met with any more scepticism than I already was but this guy just came right out with it, laughing and shaking his head like I was a fool. The worst part was that he was merely saying exactly what I felt. I couldn’t do it, I hadn’t done anything like it, what on earth was I doing continuing with this outlandish and crazy ruse? I wasn’t a sailor and only sailors sailed across the Atlantic.

I rattled my nails on my desk and tried to remember that he was always the grumpiest solicitor on the floor and clearly hated his job in construction law. It fired me up as I looked over my shoulder at him, sat in his window desk doing endless paperwork and helping development companies sue each other.

If I stayed and got the promotion I’d been going for, I would end up living a life of what-if. Maybe I’d even end up like him, laughing at the aims of strangers. Well, I wasn’t going to be swayed by his negativity, no way.

Suddenly I was more dedicated to sailing to the tropics than I ever had been before. For everyone who rolled their eyes, laughed at me or said in a chandlery that I’d ‘never leave the Solent’, I was going to get on that boat and go south until the butter melted. I looked around at the desk debris I’d collected over the last year and wondered if this was all I thought I was capable of, a job that didn’t even require you to finish school. Sod solicitors, I thought, I’m going to go sailing for me.

By April I had left my job in Exeter and moved into Alex’s house, which he was housesitting for his retired parents who were themselves away cruising for a few years.

I installed myself at the kitchen table and worked as a freelance copywriter while Alex spent all of his time at the new boatyard in Portsmouth, refitting the boat.

I went down there often to wiggle into small spaces, swing about at the top of the mast to change the rigging two stays at a time or manhandle a paint brush but, as anyone who has renovated anything will know, you have to make it much worse before you make it better.

I had no idea what I was doing, taking instruction from Alex and trusting him when he said, ‘you can remove two stays easily and the mast won’t fall down’. He’d never refitted a boat before but his attitude that one can learn anything meant that no task was too difficult, too complex. With a keel-stepped mast, it indeed didn’t fall down as I changed the rigging, two by two.

The boat had been originally fitted out for day sailing only and, aside from a very occasional cross-Channel trip, had spent its life dawdling about the Solent. Thus its fittings weren’t suitable for us and Alex stripped out everything… everything… and started from scratch.

He built lockers into cavernous spaces, added another bookshelf to stop me weeping over the lack of book space, turned the forepeak into a double bed with storage underneath, removed the microwave and installed a gas system and stove and rebuilt the entire interior piece by piece.

Every afternoon he’d park on the drive, our estate car packed full of teak in need of restoration and disappear into the workshop in the garden well into the evening.

When it became obvious that the rudder was dangerously weak and saturated with water, he removed it, cut it open and rebuilt it. He replaced every inch of wiring and created a whole new switch panel. He sat drawing diagrams for me after dinner, teaching me things that I struggled to understand.

“Wait, so the buses go to the bus station from the city and then they all split up and go to different suburbs?” I asked, searching for a metaphor that would transform my understanding of the electrical system.

“Sure,” he said, “like the lighting suburb or the AIS suburb or the navigation light suburb.”

“And the bus station is the switch panel?” I found it amazing that I’d ever got a B in physics.

The refit wasn’t just rebuilding and adding new shelves and lockers though, there was so much else. Lacking an autopilot, we researched for months before concluding that every sailor in the books we’d read had troubles with their autopilots, so we needed something that was not only as reliable as possible, but also fixable mid-ocean.

We settled on an Aries wind vane, accepting that whenever we motored we’d have to hand-steer. The fuel tank, built into the depths of the bilge, only had a 60-litre capacity anyway and we weren’t intending to use the engine much. It was only when we started talking about autopilots that I even learnt we wouldn’t be hand-steering 24/7 anyway. I had never realised that you allowed something else to steer offshore – it was immensely relieving but also highlighted again how little I knew. In fact, the entire refit showed me how little I knew.

As I typed madly for ten hours a day, writing all sorts of copy for various companies, I would be answering the doorbell every hour or two and signing for parcels.

At first I felt a little sheepish, seeing the same UPS man for three days in a row, but then it became ridiculous. With almost all of our boat bits, everything from nuts and bolts to a liferaft and aluminium poles coming from eBay, Amazon and online chandleries, I began seeing the delivery men more and more often.

I was only 24 at this point but regularly got asked if I was 17 and could only imagine what the line of UPS, DHL, FedEx and other couriers thought I was buying. ‘Poor girl, she’ll be bankrupting her parents with that shopping addiction, shouldn’t she be in college or something?’

This was compounded by the fact that the house was at the end of a cul-de-sac almost exclusively inhabited by retirees. Huge delivery vans and even small lorries would find themselves having to do ten-point turns just to get out again and the amount of noise they made alerted everyone on the road that I had a delivery. Chandleries, it turned out, do not send small vehicles.

It became a game of time and curtain-twitching; the UPS man always showed up around 11am and was usually the first of the day. That meant I could safely shower in the morning but when a spate of work came in with extraordinarily tight deadlines, I would shower after 2pm instead. This lead to a series of embarrassing towel related incidents I’d rather not go into. Suffice to say, taking parcels and having to sign for them while wearing a towel requires more hands than I possessed.

The liferaft was actually delivered to a neighbour as I had chanced a mere thirty minutes out to go to the supermarket. But delivery men have a knack of turning up at inopportune moments and I returned home to find a ‘we missed you…’ note on the doormat.

I took a deep breath and headed over to number 14, ready to profusely apologise for dragging them into my Cirque de Delivery, especially since I was aware that the raft would weigh upwards of 20 kilos.

The neighbour was pruning her hedges around the back and it took a few doorbell rings for her to hear me. She was tiny and smiley, batting away my apologies with her secateurs. The liferaft had been left just round the side and it was soon apparent that I would seriously struggle carrying it back across the road and up the slope to the house.

I considered asking her if I could leave it there until Alex returned home but I already felt bad about troubling her with it. She had other ideas though and said she’d help me carry it across. Now I was in trouble, I thought. Not only had some FedEx guy got her to sign for a 23 kg liferaft, but she would have to somehow help me carry it up a hill.

She wouldn’t have me refuse though and we took a strap each and lifted. Now I consider myself reasonably strong, I’m a rock climber and have little trouble hefting around boxes. But the liferaft was an awkward and dense object to carry and it would’ve taken me stop-starting it across the road. My small, retired neighbour, however, picked up the strap with one hand and lifted.

“Ready?” she said. I nodded, wide eyed.

Out of the two of us, I’d freely admit that she carried it with greater ease than I and she merely dusted herself off when we reach my patio and said no trouble, she’d sign for anything if I was out again.

She went off down the drive, back to her hedges and I wondered if she had a secret weights room out the back. Never underestimate the strength of your elders. We still send her postcards.

It took a year for us to complete the refit as far as completion was possible anyway. Boatyards and marinas are full of yachts that just need a ‘few more jobs’ doing before they are ‘ready’. But then you’ve worked on through the season and maybe you’ll be ready next year instead.

We did not want that to be us for several reasons. Firstly, we wanted to be sailing south, not working away through another British winter and secondly, boats are expensive things and we could only afford to have one if we lived on it. No more car, no more bills, no more excess that life in a house encourages. We had to move onto the boat ASAP and be on our way to places where we could anchor for free.

This was the party line, we were sticking to it. But in my head the constant worries repeated themselves and the bizarre double-crosses of my thoughts created an on-going internal battle. Maybe there’d be a huge storm, the boat would fall over and this whole thing would be abandoned. Maybe Alex would get sick of the relentless fiddly jobs to do and we’d just sell her. Maybe I wouldn’t have to go to sea, something I still couldn’t even comprehend. No one was holding a gun to my head except me though. At any time I could’ve stepped in and said, ‘I don’t think I want to do this’, but I didn’t.

I didn’t say it not only because I was deeply afraid of what it would mean for us as a couple, but also because it wasn’t even true. It was a sentence that in some way described how I was feeling but it wasn’t complete. I did want to sail around exotic islands and swim in warm waters. I did want to experience the pure adventure of being out on the ocean thousands of miles from land. What the real sentence should’ve read was, ‘I don’t think I can do this’.

But saying you don’t want to do something implies integrity, decision-making and strength; no one can argue with that. However, saying you don’t think you’re capable of doing something is much more easily countered because it’s a weak statement easily batted away with, ‘why not?’

While I tend to live my life with as much organisation as group of drunken students, Alex is the sort of person who knows what a Gant chart is. Every month he’d tick off his boat projects and tasks and be more on less bang-on schedule. I would watch over his shoulder with my jaw on the floor; I knew you could plan things, but I didn’t realise that it actually worked.

If I write a to-do list I’ll populate it with things I know are within easy reach; buy bread, reply to editor, text Sophie. Alex creates a time estimate and difficulty rating for each task and performs it with rationality and enthusiasm. He’ll even break down tasks into smaller ones.

It was this attitude and drive that allowed us to put the yacht into the water just two weeks later than had been planned a year before. She’d been in the water for three months the previous summer and we’d ventured on brief day sails around the Solent, but this was it, this was the launch.

When people go off on gap years or leave to move to another country, there are parties and farewells. After all, it’s an easily categorisable event. You are getting on a plane in a week and won’t return for a year or two, let’s throw a goodbye party on the Friday before!

But sailing isn’t like that, not our kind of sailing. For all of Alex’s enthusiasm, he knew perfectly well that something might go wrong and we’d be back in a month. Or perhaps we wouldn’t end up leaving Britain’s shores at all. Maybe we’d only get to Falmouth. And from my point of view, I just didn’t believe we’d get any further than France. I couldn’t imagine it, besides, I’d always lived in the UK, how did it even work, to be nomadic?

Neither of us knew how long we would be gone for or where we would end up. We reassured each other that simply spending a summer sailing to Portugal and back would be fun. If we made it to the Canaries then the Atlantic might beckon but I wasn’t so sure. Either way, we made no official date for ‘leaving’ and were purposefully vague about our departure. If for no other reason than a cruising departure isn’t really a departure anyway, we might launch from Portsmouth only to spend several days in an anchorage a few miles away and then we’d spend a month or so pottering along the English coastline before even attempting a channel crossing. We didn’t know when we would leave leave. So we didn’t really tell anybody.

We stayed on the mooring for just three days until we left in a force six that Alex optimistically said would only be a nice force five once we got out of the harbour. We were heading for Newtown Creek, it was Wednesday the 7th May 2014 and it was our three-year anniversary.

“Something’s wrong,” I said a few miles into tacking to windward. “The wheel feels loose.”

We swapped places and Alex told me to get ‘the number thirteen spanner’ and fast. The boat was speeding towards Gilkicker Point at 6 knots but at least the boat was balanced, an important quality in a boat without steering.

Alex knew exactly what the problem was instantly, mainly because it was something that he’d sort of caused. The wheel and the rudder had disconnected, the rudder stock having slipped after being altered slightly in the course of the rudder being re-built.

Alex fixed it quickly as my heart was hammering in my ears, audible against the howl of the wind and we tacked at the last second, a dog walker on the beach looking at us, probably with the kind of expression people get when they’re about to see something they should film and put on YouTube. A yacht hurtling towards the beach, improbably close.

The wind was a steady force seven and we were the only yacht out in the Solent, which was refreshing. The busiest shipping channel in the world, the Solent is normally chock-a-block with people on every waterborne object imaginable with a few container ships and cruise liners thrown in for good measure. It’s not even unknown for clusters of people to swim across it (I should know, my mother’s done it) with a kayaker or two as escorts.

While this was only day one of our adventure, I’d already had many sailors nod appreciatively at our little boat on the pontoon and say, ‘real round-the-world boat you got there.’ This day of ploughing head first into a 27 knot south-westerly certainly did incline me to agree. Sure there was no ocean swell but the yacht didn’t seem to mind about the nasty chop or the raging wind, if nothing else, she seemed to relish it.

I huddled in the corner under the spray hood as Alex helmed in his genuine Guy Coton yellow jacket, fresh from France, making him look like a traditional fisherman. I unfolded my cold body only to tack and each time Alex talked me through it – I still had almost no idea how to sail.

Portsmouth Harbour to Newtown Creek is 11 nautical miles on a good day but, when we finally dropped our anchor in the soft, black mud, we’d done 45. The harbour master appeared in his RIB, gobsmacked to find a yacht in his midst when it was gusting force 7.

He repeatedly reassured us that we could pick up a buoy for free any time we felt the wind was too strong and were we quite sure that we were alright? I felt bad that he’d come all the way out in such weather but I was so happy to finally be stopped that I was almost swinging from the rigging.

In those early sails, arriving at anchor made me giddy with achievement and filled with the happiness that you only get from coming in from the cold to warm your hands on the fire or, in my case, the engine bay.

We stayed in Newtown Creek for a wild and windy week, trapped by a gale that made us thankful for thick Isle of Wight mud. We escaped once by dinghy and walked to the local pub. We were only a few miles from where I grew up across the water, but the sense of adventure I felt merely from having sailed there myself was overwhelming.

There was very little that had previously excited me about the Isle of Wight, it being an ever-present sight throughout my childhood. I’d been there plenty of times before but now that’d I’d battled wind and waves to get there, it became a Blyton-esque treasure island where every footpath lead past Kirrin cottage and every shore could hide adventure. In short, sailing reverted me to an excitable form of childhood.

While this was supposed to be the start of our ‘shakedown’ cruise, we realised that an adjustment needed to be made to the rudder stock to prevent it slipping ever again and plunging us suddenly into danger. That would require finding a welder and so, when the wind chilled out, we sailed across the water to Hythe, a town in Southampton Water.

After the previous year of refitting, Alex had got a feel for the industrial parks around southern Hampshire and within a week we were off for shakedown cruise part deux with the rudder stock altered.

This time we were to attempt a journey that had been weighing on my mind for months. A Channel crossing.

By this point I’d still never left the Solent. We’d practised picking up buoys in Portsmouth Harbour, I’d raised the mainsail a few times and I could reef the genoa. But that was about it. I believed even the slightest wash would threaten us with capsize (even after Alex explained that it was incomprehensibly difficult to capsize a boat like ours and basically impossible to do so in sheltered water. Not to mention that our righting angle was 160° so ‘if we did capsize, which we never will, we’d pop right back up anyway’).

We anchored in Totland Bay on the western end of the Isle of Wight and set sail at 6:30am with a friendly westerly wind. I’d been diligently making passage plans for every tiny sail we’d done so far, mainly because Solent and Channel tides are a force to be reckoned with, and was pleased with the apparent simplicity of the crossing.

It would take around twelve hours and the Channel tides are semi-diurnal, meaning that for half the journey you’d be swept to the side in one direction and the next half you’d be swept to the side in the other direction. Thus the tides politely cancelled each other out. A unique attribute to the Channel, it seemed as though the tides had created themselves purely for the pleasure of English and French sailors. The crossing was north to south, the tides east to west.

We hopped on the ebb tide that rushed between Hurst Narrows where the Isle of Wight and the mainland sit closest to each other. A few miles offshore Alex taught me how to hove-to, something which I promptly forgot mainly because I really needed to pee and we’d been on an uncomfortable tack for the toilet.

Beam reaching the whole way, I was surprisingly not nauseous at all even though I often had been when rolling about in the chop off Portsmouth Harbour on previous trips out. I slept on the leeward cockpit seat for a couple of hours, lulled by the soporific motion of the sea and Freya, our wind vane, steered us with ease.

As we closed in on the island of Alderney, heavy clouds crept up from the south and lightning began to appear. Of all the things that freaked me out about sailing, the idea of being struck by lightning was one of the main ones. Wind and waves were manageable to an extent but lightning was nature set to random and it made me nervous.

The current around Alderney is a determined thing and while Alex was concentrating on directing me so that we wouldn’t be set down too far east, I was busy praying to a God that I didn’t believe in that we wouldn’t be struck by lightning. After all, out there you can’t help feeling that you’re a ten-metre lightning rod in an empty sea.

We arrived in Alderney Harbour at 8pm and anchored, avoiding the mooring buoys and their charges. The water taxi came out to us, following a downpour and the woman cheerfully welcomed us to the island and gave us a couple of leaflets, one detailing the protocols for ordering duty-free alcohol. It was obvious why most British sailors hopped over to Alderney for the weekend.

I was salty and windblown but drumming my hands on the walls in excitement; this was more than sailing to the Isle of Wight, this was a new country! Well, not a new country exactly as Alderney exists in the strange, semi-autonomous archipelago of the Channel Islands and uses the pound but still, it wasn’t England per se. It wasn’t even EU.

The magic of Enid Blyton had followed me well and truly to the Channel Islands, especially as Alderney was riddled with wartime fortifications that were either abandoned or seriously eerie. With hidden tunnels and wild, overgrown fields, it was a windswept place with a beauty all of its own.

We sailed to Sark a week later and the feeling was compounded. Sark was still based on a feudal system and seemed to exist wholly outside of the world as we knew it. Relying on supply ships from the larger islands, Sark had a tiny population and no motorised vehicles. We stayed for a lumpy two nights before catching a weather forecast while paying exorbitant 3G roaming fees and prepared to flee for Guernsey.

Because of an increase in swell the night before, Alex had rowed out a kedge anchor to keep us bows-to the incoming swell. The bottom was thick, heavy kelp and we had a significantly more comfortable night than we would otherwise have had.

I stowed things for sea while Alex rowed back out to retrieve it. He returned quickly with a whole load of chain but no anchor.

“I forgot to cable-tie the shackle,” he said dumping the chain into the cockpit, “I’m going to have to dive for it.”

I did not envy him the task of getting into Sark water and he donned his ancient winter wetsuit, complete with its holes, and jumped overboard with a dive torch. He swam until he was numb but the kelp had long since absorbed the anchor into its dense, oceanic meadow.

We figured the swell must have steadily rocked the shackle pin loose as we slept but kept repeating ‘what are the chances’. It wasn’t a mistake we ever made again.

We set off into the increasing swell for the shelter of Guernsey and were only mildly comforted by the fact that the anchor had been free from a friend. Still, it would be expensive to replace.

Within a couple of hours we were nestled in Fermain Bay, a shallow cove with a small and pretty beach just to the south of St Peter Port. We were the only yacht there and we’d arrived early evening when Sark became untenable.

I was in bed by 10pm and the night was still and moonlit in the shelter of the bay. We’d tucked close into the shore and checked the tidal range but a while later Alex poked his head into the forepeak and told me he thought we might ground – he’d miscalculated.

He said he’d re-anchor himself, the water was smooth and there wasn’t even the smallest hint of wind. I closed my eyes again and kept an ear out for the activity on deck.

By the sounds the engine was making, it was clear that all was not going to plan. I hopped out of bed as Alex called to me and went to investigate.

The anchor was stuck on something on the seabed and the tide had dropped, fast. We were minutes from grounding and after one last attempt to free it from the surface, we were forced to tie a fender onto the end of the chain and throw it overboard. Anchorless, we retreated to an unused fishing boat mooring buoy and tied the boat on.

The moon was almost full and lit up the still water. The white fender looked grey in the half-light, a ghost sitting firmly on the surface. We decided that we couldn’t stay on the buoy all night; we had no idea what sized boat it was designed for but probably not an 8-ton yacht.

“I’ll have to dive for it,” said Alex, heading for the wetsuit cupboard for the second time that day. I pulled a face, I wanted to help but there wasn’t a chance I was going to get into that temperature water. Just thinking about it, I could feel the freezing water leaking into my wetsuit around the neck. I shivered.

We pumped up the dinghy and left Berwick Maid silently sat on the buoy, her halogen deck light creating an almost biblical beam of light onto the foredeck.

We hauled the fender into the dinghy and Alex went over the side. I pulled the chain into the dinghy, just a few metres to keep the dinghy in one place, and watched as Alex tracked the chain back to the anchor with his dive torch.

I hauled in a couple more metres, the chain lying across the width of the dinghy. A link pushed against the air bung and knocked it out as I squealed with surprise. A precarious thing at best, the bung could be knocked out with a fierce look and the inner mechanism had long been broken, allowing air to whoosh out. I scrambled for the bung, now somewhere in the bottom of the dinghy and felt the tubes begin to soften. I grabbed it, dropped it and grabbed it again, ramming it back into the hole. What else could possibly go wrong?

“It’s caught through some kind of iron loop,” he said as he swam back to the dinghy. “I’ll detach the anchor and pull the chain through one side and the anchor out the other.” I passed him a pair of pliers to cut the cable tie around the anchor shackle and he disappeared again.

For some reason, we loaded most of the chain into the dinghy before he went to retrieve the anchor and the dinghy started drifting, ever so slightly back towards the boat.

His huge free diving fins were kicking up billowing clouds of sand as he tried to stay above the water helping me with the chain and by the time he turned to get the anchor, it was obscured in a pale and opaque mist.

There was a few metres of chain out, anchoring the dinghy, but our movement had still allowed it to drift. He swam frantically with his torch trying to locate the anchor but each kick sent more sediment into the water.

I sat in the dinghy with wide eyes, running through the consequences of losing our anchor again. This time we didn’t have a spare. We’d have to motor up to St Peter Port and tie up to a pontoon. How much did new anchors cost?

The was a splash and a shout and I realised that I was still drifting slowly, the weight of the chain in the dinghy too heavy for the remaining chain to hold still.

“I found it!” he called. He swam the 15 kg anchor back to the dinghy and loaded it in, I was overwhelmed with relief. We rowed a slightly soggy dinghy back to the boat and re-anchored in deeper water.

When we arrived in the Solent after two weeks exploring the Channel Islands, I finally felt like this was something I could see myself doing. By this point I had yet to experience any ocean swell but at least I had made peace with the idea of living on a boat. Besides, if I’d known what how hard it was going to be, then I probably would’ve needed a lot more convincing.

We spent a further two weeks in Hythe Marina, seeing friends and tying up the last loose ends. By this point we had no idea how long we’d be away –I think I thought it was going to be more like a few months than a few years. But we had no real reference points because we didn’t really know where we’d end up going. This made saying goodbye or explaining the situation to banks all the more difficult.

We made no fuss of actually leaving. Leaving, leaving. In the back of my mind was the very real possibility that we’d get to Cornwall and think, ‘screw this’ and just go for a nice summer trip to the Scillies before coming home. I liked the idea of living on the boat now, but I still wasn’t all that sure it was a long-term situation.

The boat was full of food, tinned and fresh. The water tank was full, as was the fuel. We’d closed up the house and said goodbye to friends and family. We slipped our mooring, negotiated the lock out of Hythe Marina and headed out down Southampton Water.