0,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: inDrive

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

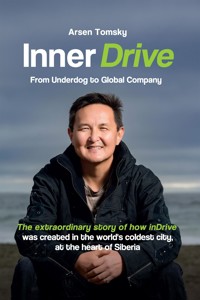

The extraordinary story of how inDrive was created in the world’s coldest city, at the heart of Siberia

“A compelling and moving account of what can be accomplished when someone focuses on the opportunities, not the obstacles.” -JESPER B. SORENSEN, SENIOR ASSOCIATE DEAN FOR ACADEMIC AFFAIRS, STANFORD UNIVERSITY

Embark on an extraordinary journey with Arsen Tomsky's

Inner Drive: From Underdog to Global Company, a captivating tech entrepreneurship memoir that chronicles the rise of a startup success story against all odds. From the frozen landscapes of Siberia to the competitive arenas of Silicon Valley, Tomsky's narrative reveals how a small team with limited resources challenged industry giants in the global ride-hailing market. This business memoir offers invaluable insights into ethical business leadership, overcoming adversity, and the power of purpose-driven companies. Tomsky's candid account of building inDrive demonstrates how embracing a mission to fight injustice can fuel organic business growth and create social impact at scale.

Readers will discover a new approach to blitzscaling that prioritizes positive change alongside profit, challenging traditional capitalist models. The book delves into the complexities of developing markets, international economics, and the unique challenges faced by Russian tech entrepreneurs. Tomsky's journey, filled with triumphs over corrupt officials and navigation through global crises, illustrates the transformative power of resilience and ethical decision-making in business culture.

Inner Drive is more than just a story of startup success; it's a blueprint for aspiring entrepreneurs and established leaders in business management. It explores the intersection of technology, transportation industries, and social good, offering a fresh perspective on business growth and development. Tomsky's commitment to nonprofit initiatives and philanthropy showcases how companies can thrive while contributing to social sciences and charity. This inspiring tale of personal transformation and professional achievement will resonate with anyone seeking to make their mark in the world of international business and beyond.

What people are saying about this book:

Entrepreneurs are heroes, especially those who break molds, create new businesses, and help provide for the livelihood of their teammates and partners. Arsen and his story are extraordinary. A super smart guy from the coldest place on earth - Siberia - is bound to see the world differently when he sets out to explore it. 'Inner Drive' is filled with inspiration and 'you must be kidding me' moments but the proof of success is in the rapidly growing company he continues to build in emerging markets around the world. MARY MEEKER, GENERAL PARTNER AT BOND CAPITAL

A compelling and moving account of what can be accomplished when someone focuses on the opportunities, not the obstacles. Arsen Tomsky's relentlessly creative and curious mind is coupled with a positive spirit motivated to drive positive change in the world, from Siberia to Latin America and Africa. JESPER B. SORENSEN, SENIOR ASSOCIATE DEAN FOR ACADEMIC AFFAIRS, STANFORD UNIVERSITY

Arsen Tomsky - serves as a true model for anyone living with stuttering. His personal and powerful message provides inspiration to those of us facing adversity and challenges. GERALD MAGUIRE, MD, FORMER BOARD CHAIR OF THE US NATIONAL STUTTERING ASSOCIATION

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Inner Drive. From Underdog to Global Company

Copyright © 2024 by Arsen Tomsky

All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

Published by inDrive

[Contact for publishing if applicable]

Table of contents

Cover

Dedication

Foreword

Part One

Part Two

Part Three

Part Four

Part Five

Epilog

Acknowledgments

Copyright

Back Cover

Cover

Dedication

Foreword

A sea of clouds stretched out far beneath me in an endless expanse, concealing the Tanzanian savannah below. Mawenzi Peak rose through the cloud cover to a height of 16,890 feet, and I was 1,600 feet higher than that. I was on my way to Gilman’s Point, at the rim of the crater on top of Kilimanjaro, the tallest mountain on the African continent. Above everything, the sun rose, gradually painting warm, gentle colors across the early morning sky. My two climbing companions stood silently beside me, awed and entranced by the intense beauty before us.

I thought about the summit, which was still two hours away. Only two hours remaining of a six-day climb. I was exhausted; we’d been climbing eight hours already through the night, and I was battling intense nausea and a splitting headache—the effects of mountain sickness. I knew that I would make it to the top, but I couldn’t help thinking how terrible it would be if I didn’t. I started thinking about how a moment like this would be a powerful gestalt, something that could consume a person entirely, take them over, dictating their subsequent actions and manipulating their mind. Not so different from the path of an entrepreneur, I thought, or life in general, where we mark out our own summits, and the failure to reach them leaves wounds that can damage or even destroy our very sense of self. As we strive toward our peaks, the fear of failure, of not making it all the way, saps our confidence and our strength, preventing us from enjoying our lives and work, as well as the journey itself.

At that moment, I was struck by an insight, consumed by it and held captive in its grip. The mountain sickness, fatigue, the natural beauty—it all faded into the background. It all had to do with the goal! If you make your goal to “conquer the mountain” (sounds funny, doesn’t it? The mountain is, after all, entirely indifferent to whoever might be tramping around on it), if you decide on a single, specific objective, where the possible outcomes are only victory or defeat, 0 or 1, where it doesn’t matter if you missed your landing jumping over a chasm by just a hair or never had a chance—well, that’s a weak position, one in which you’re vulnerable to manipulation.

But if you flip the coin over and make your goal new experiences, new impressions, self-realization, and, most importantly, development, you’re in an entirely different situation. You’re not conquering a summit—you’re climbing upwards to grow stronger and better, to attain something of value in order to share it with others. Here, even if you don’t reach the top, but do everything you can; if you act with intelligence, energy, and talent, then, although it might not be victory, it certainly won’t be defeat. What you will have achieved can’t be taken away, and you’ll avoid that trap of fearing failure, fear of the 0. This new goal positioning will give you strength and confidence, freedom from fear, and you’ll be more likely to reach the top than if you’d been focusing on “conquering” it. What’s more, you’ll enjoy the process of the climb.

I took a picture of the panorama, and then we set off again. A few hours later, we stood on the summit, holding each other, tears of joy in our eyes. We’d become happier, stronger, and better on this trip—taking one more step along the path of development.

The inDriver story begins in Yakutsk, the coldest city in the world if we’re counting population centers with 10,000 inhabitants or more. The city is in southeastern Siberia, barricaded to the south by mountains, with its northerly flank exposed to the cold air masses that blow down from the Arctic. It’s in something of a frost pocket in the continental interior, far from the coast. The result is winter temperatures that fall to -50 or -60 °F, and can even reach -75 °F or lower. In parts of Yakutia, the vast, wild, and pristinely beautiful region of which Yakutsk is the capital, temperatures can fall as far as -90 °F. Winter lasts for much of the year, from around mid-October to early April. Summers are short and hot, populated by gnats and mosquitoes.

This was the land settled many centuries ago by my people—the Sakha, or, as the Russians call us, Yakuts. Research tells us that our ancestors came from one of the Turkic steppe groups who had settled to the east of Lake Baikal by the early Middle Ages. They were later forced to migrate northwards, mostly to escape hostile Mongolian tribes. Their choice must have been to either head north or risk the loss of life and liberty. Why else would horsemen from the southern steppes resettle in the coldest inhabited place on earth? Curiously, the language of the Sakha still contains the words for “camel” and “lion” despite the fact that no such creatures exist in Yakutia.

These are difficult conditions to survive in, but our ancestors managed it. Perhaps it is this harsh landscape that gave rise to some of the distinguishing qualities of the Sakha people: ingenuity, perseverance, skill in commerce, and excellence in the hard sciences and visual arts.

Building an IT company in Yakutsk is far from easy, yet still I chose the path of a tech entrepreneur. We’ve had our ups and downs, and there were challenges to overcome along the way, but step by step we’ve succeeded in launching and developing several successful IT businesses and nonprofit initiatives.

In this book, I tell the fascinating story of inDriver, which began more than 10 years ago and continues to this day. In order to understand the whole story, we start from the very beginning: I recount episodes from my life that illustrate how I developed as an individual and a leader, how our team was born, and how our culture and supermission took shape. As we go along, I will share the ideas and resources that have enabled me and my team to create, against all odds, a unique and compelling story. It is a story almost without parallel in the entire history of the startup movement—a major global company founded in a small, remote city, under the most difficult conditions imaginable and without any support. Based on the values of personal, professional, and community development, and giving back to the world in which it operates, this company is now impacting the lives of people everywhere, from the steppes of Central Asia to the villages of the Maasai in Africa, from the volcanoes of Kamchatka in the Russian Far East to the peaks of the Andes in South America, from the Florida Keys to the Egyptian pyramids.

My primary goal is to motivate people to seek personal development and find a way to contribute to others, no matter the circumstances of their lives. I intend to do this by revealing sources of strength and resources for growth that are far more profound than anything you will get by using the practical business techniques and methods typically found in books, seminars, and business school.

Our adventure with inDrive is at its height, which will make it all the more interesting for the reader to find out what happens next. So, let’s begin.

Part One

Programmer

“Everything that touches your life is an opportunity if you discover its proper use.” - William Wattles

Yakutsk in the late ’80s wasn’t an easy place to live. The country was falling apart, accompanied by a massive deficit and grinding poverty; people were disoriented and at a loss. The ideals of communism and socialism had been tossed onto the garbage heap, and nothing had come to take their place.

I was an ordinary kid, maybe a little nerdier than the rest, coming as I did from a family of scientists. My family worshiped at the altar of science, so our home was full of academic literature, books, and journals. By the age of 12, I had read through most of the classics of children’s literature, from Alexander Dumas and Jules Verne to Charles Dickens and Francois Rabelais.

I didn’t display any particular entrepreneurial inclinations or aspirations, didn’t have a lemonade stand or sell stickers to my classmates and neighbors like many famous businessmen did in childhood. I was, in fact, fairly indifferent to money. Once, when I found a few rubles on the sidewalk (a not-insignificant amount at the time), I just took my entire class to the shop and treated everyone to poppy-seed rolls and milk. Another time, the boy I shared a desk with at school showed me a wad of cash, 40 rubles, that he’d taken from his mother’s nightstand. I immediately demanded, and received, half the money as the price of my silence. But at the start of the next lesson, the teacher announced a fundraiser for the children of Nicaragua, a frequent occurrence in those years. Without thinking, I donated the 20 rubles I’d just extorted, which led to a quick investigation on the part of the teacher and the return of the entire sum to my classmate’s mother.

It was around that time that my father left. I remember him squatting down, taking me by the shoulders, and telling me this was for the best—that it would be hard, but it would toughen me up. And then he was gone, and that was the last I saw of him for 15 years. But this wasn’t a traumatic episode for me; in fact, it was one of the best things to happen in my childhood. He treated me quite harshly, sometimes even cruelly, especially when he and my mother weren’t getting along. Perhaps the most important thing my father, a famous mathematician and professor, gave to me was his genes, particularly in terms of scientific ability and logical and algorithmic thinking.

For my birthday, during the year we lived in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), my parents gave me a programmable ATV. It was a buzzing, self-propelled toy vehicle; you could enter in simple commands like “one meter forward, make a ninety-degree right turn, go a half-meter backward, shoot twice.” It was probably this moment of discovery, the first time I felt like the architect of an intelligent force, that gave rise to my interest in programming. I gradually began to read everything I could find on computers (without ever having seen one and having no way to get access to one) and programming. This was mostly in journals like Science and Life that our family had subscribed to for many years. It’s amazing how little it can take to spark a child’s interest and turn him or her toward a future path in life.

My mother was one of the most highly educated women of her generation. Her brilliant mind, erudition, sense of humor, and kindness were matched by her beauty and charm. I loved my mother very much, and still do. Several years after my father left, she fell seriously ill and was in and out of the hospital for some years after that. The only person we had to help us was my elderly grandmother, a person of great wisdom and kindness. Most of our other relatives left us to our own devices; they had enough problems of their own. It was then, at age 12, that my childhood ended and the struggle for survival began.

When I was in fifth grade, our school in the city center was merged with a different school from the working-class city limits. The school culture changed and grew violent, aided by the chaos engulfing the country as the state weakened. Studying was looked down on, and the delinquents were in charge; many of them later ended up in prison or dead. The teenagers split off into gangs and feuded with one another. The teachers did little to help, and I had a tougher time at school with each passing year. My speech problems made it worse: I’ve had a pretty bad stutter since childhood. It was so bad I even had trouble making a simple purchase in a store. But I tried to adapt and fit in—I went around with other guys ransacking houses when the owners were away, stealing little things, or taking money off strangers who came into our area, sometimes with a beating. One thing we didn’t get into, though, was alcohol, let alone drugs, probably because of the massive deficits throughout the country.

A couple of years of being almost an orphan in that aggressive environment made me a hard, completely independent, and capable person, prepared to withstand anything life could throw at me. I’ve wondered since then which is better in the end—a happy childhood, with everyone loving and indulging you, leaving you (it seems to me) a happier person for the rest of your life, or a childhood full of trials that builds a strong character with a solid inner foundation, one that readies you for constant struggle. Interestingly, a life full of challenges often produces, along with strength and resilience, a certain inferiority complex that can serve for the rest of your life as a powerful drive to prove to the rest of the world that you deserve recognition.

Care and love from childhood or trials and toughening up? I had the latter, but I have to note as well that I came right up to the precipice of destroying my chances in life.

I’ll give you an example.

Just after midsummer at the 62nd parallel north, the white nights begin to grow darker. On one July night, four small figures crept silently in the dim light through a courtyard in the center of Yakutsk. The teenagers reached one of the parked cars and began to push it away from the curb. There was no other sound except the wheels rubbing against the pavement, and it felt like the whole world could hear the wild beating of our hearts. We were only 13, and we’d decided that we couldn’t call ourselves really bad boys if we’d never boosted even a single car. The car was parked right downtown, and it belonged to one of our uncles. This model was known for its small size and incongruously loud engine. The muffler had also been removed from this particular car, which made its operation truly record-breaking in volume. So, to avoid waking anyone up, we quietly rolled the car 1,000 feet away from the courtyard before we jump-started it.

We drove around the sleeping city victoriously revving the one-liter engine. Riding high on the adrenaline rush from our successful crime, we, like any bunch of criminals, naturally decided to acquire some weapons. One of us remembered that his friend had an air rifle, the kind that shoots tin pellets at metal rabbits in shooting ranges. On our way to the friend’s house, we passed a police SUV out on patrol. Seeing a car full of teenagers, they did a quick U-turn and signaled us to pull over. Our driver responded by jamming the gas pedal to the floor, starting off a wild chase through the entire city. On the outskirts, we skidded into a ditch on a hard turn, and our escape attempt was cut short by a huge barbed-wire fence 500 feet ahead, the perimeter of some guarded facility. The police caught up to us and gave us a brutal beating right there, handcuffed us, and took us to the station. Only the smallest member of our group escaped this fate—he managed to hide in the tire from a large truck lying nearby, and they didn’t notice him.

At the police station, they took our pictures, and were getting ready to start case files on all of us. But the owner of the car showed up shortly after dawn. Fortunately for us, he said that he wasn’t going to file a report, and he talked them into letting us go. We were lucky that one of us was his nephew. Otherwise, best-case scenario, we would have had court records, and worst case, we could have ended up in juvenile detention. I doubt I’d be writing this book today if things had gone that way.

My stutter first appeared when I was about four. I got it from my father; I’m not sure how that works, but apparently children can start subconsciously imitating the behavior of the strongest personality in their life. They said my speech could also have been affected by the strong fright I got when a sheepdog jumped down on me from the top of our shed and bit me. In any event, I don’t have a genetic, physiological, or untreatable defect, but an acquired stutter. It was barely noticeable at times, but sometimes it got so bad I didn’t even want to leave the house.

People who can speak without difficulty have trouble understanding just how humiliating and painful it can be for a child or teenager to stand in front of another person, or worse, a group of people, straining and pale, trying to produce a few simple words.

The stuttering worsened my social isolation from my peers and damaged my self-esteem. It’s a terrible thing for any child, and if you encounter these children or adults, please treat them with tact and kindness. Teach your own children to be kind to anyone dealing with any type of physical disability. It’s not anyone’s fault. It’s just the way things are, the cards dealt by nature, and nothing to be ashamed of. Stuttering is difficult to treat, and I’ve put a great deal of effort into improving my communication skills over the years—more on that later. I’ve yet to completely rid myself of it, but I rarely think about it these days, and I consider it just another interesting feature making up my personality. Truly, in life as in athletics, if you go the distance wearing weights around your ankles and win anyway, your success is that much more significant than if you ran weightless. Stuttering did, in fact, prevent me from engaging in unnecessary chatter and communication, kept me at a distance from politics, and forced me to focus on work. Also, as I will describe later in the book, stuttering gave me an additional source of motivation and inner strength. Viewed through this lens, it was a defect that turned out to be a valuable gift.

Starting from age 12, I spent my summers working in a village. My first summer, they had us weeding cabbages in the fields of the local sovkhoz, the state-run farm, or hunting the gophers eating the crops. But mostly I worked on construction teams of students from the nearby schools and university to build wooden fences along the edge of the forest to keep cows and horses from wandering off into the taiga, where they could die from starvation after getting lost—or from an encounter with a hungry bear. We put up about 10-20 miles of fence that summer, and it was difficult work for a city kid, but it was also the first time I experienced what real, hard work was like, and what it felt like to earn money doing it. I learned how to use an ax, a saw, and other tools. What a time—the romance of working together with other young guys and girls; the incredible sunsets; the way a simple dish of pasta with meat sauce tastes when you eat it on the stump of a tree you just cut down, in the shade of the northern forest; swimming and volleyball after a day of hard work; or trips to the dance club in the next town over, and all the adventures that went with it. I think that experience of physical work is an important one, but I don’t know how kids growing up in the city today can get it.

At the start of the school year in ninth grade, I was surprised to find two of my friends missing. They always had the top grades in their class, which earned them more humiliations and beatings than the rest of us. I called them, and heard the amazing news that they had moved to the physics and mathematics high school run by the local state university. But I was even more stunned to learn they had actual computers in their school, and students were allowed to work and play on them! It was practically the only place in Yakutsk where people my age had access to computers. After that, with the support of my mother, I did everything I could to transfer to that school, where they had what I’d been dreaming of for so long: computers.

The admissions period was already over for the year, and I had ended eighth grade with Cs in many of my subjects, but I was accepted into the new school nonetheless. My good grades in math and geometry had something to do with it, as well as the teachers’ belief that I must have inherited some of my father’s abilities. By that point, he was recognized as the top mathematician in Yakutia, the first Sakha to earn an advanced doctorate in the field.

I proved them right almost immediately, although perhaps not in the manner they expected. A few weeks after I enrolled there, the school was holding a math Olympiad. I’d never heard of these competitions, and thought it was just another boring test. I solved four out of the five problems, but couldn’t figure out the fifth. I saw that my neighbor had solved it, and, since everyone in this school looked like helpless nerds in comparison to my former classmates, I demanded that he let me copy off him, under threat of physical violence after school. I got the best score in the class, and the second-best in the entire school.

The next day, our math teacher, who happened to also be the vice-principal, called me, the newly discovered child prodigy, to the blackboard to explain how I had solved all the problems. When I got to the problem I had copied, I fell silent. The vice-principal and the entire class gazed at me expectantly. There was nothing for it but to confess that I’d copied the answer from my classmate. I hunched forward, waiting for the ax to fall. In my old school, the teacher would have yelled at me, given me a D, called my parents in, and so on, but this teacher just burst out laughing, and then announced she was putting me on the team for the republic-wide Olympiad. A month later, we came in first in both individual and team scores and won the Yakutia championship.

After that, it was clear that this was an entirely different kind of place—and it was my place! I delighted in my studies in this fantastic school, surrounded by smart, motivated students, and I made some great friends there. I also discovered another fact that was of no small importance to me at the time. One day, just after the Olympiad, I was in the hallway between classes, just leaning against the wall, hanging out. The prettiest girl in our year walked past me, a vision of perfection, and then she turned her head and shot me a look filled with intrigue and intoxicating promise. She was flirting with me! In my old school, all the attention of the fair sex was directed at the worst delinquents. But now, to my surprise, it turned out that girls were attracted to me (the same thing happened later in university, after I won a programming competition).

This was a momentous and gratifying discovery for a 15-year-old, as you can imagine.

After graduation, almost all of us got into universities—even the most prestigious and highly competitive ones—without any trouble. In school, as in any group, it’s important that the right values are being taught by teachers who care (the same in companies, but by leaders), who support the development of their students and cheer for their successes, instead of looking for who to blame and ways to punish them for unavoidable mistakes.

Computers! The first time I saw them in my new school, touched them, heard the magical whirring sound of disk drives, tapped on keyboards, smelled electrical static and plastic, it was a shock to my system. (It’s still one of the best moments of my life, along with the first time I saw the internet, or when, many years later, I had children.) These were the latest DVK-3 black-and-white computers, with RT-11 operating systems, developed in 1970 by DEC, long before MS-DOS. They had 5-inch floppy disk drives (the disks didn’t last long in them), and they supported BASIC and other high-level programming languages. This was a big step forward in comparison with the previous generation of computers, which used the inconvenient punch-card and binary programming languages. We could also play on the computers. For us, children of the USSR who had never seen computers, smartphones, or tablets, the coolest game was a simple black-and-white game for digital clocks, where a wolf caught falling eggs. These DVK-3 games impressed us way more than the most high-tech modern VR/AR Full HD game you could dream up. We spent hours playing Stalker, Tetris, and other text-based games. The administrator of the computer class, who was responsible for giving or withholding access, was a god to us.

I immediately learned BASIC and started writing programs—and understood at once that this was it for me, the one thing I wanted to do more than anything else. Programming isn’t the simplest undertaking, as a rule, but it came easily to me, probably due to the naturally algorithmic way my mind worked. It’s really an amazing thing—you turn your idea into code, and the computer obediently carries out your idea, whether it’s a simple text-based game or a complicated mathematical calculation that can’t be solved any other way. Programming, like design, engineering, and many other IT professions, is incredibly creative work, and it produces clearly visible results that can be utilized by thousands or millions all over the world. Sometimes it seems almost miraculous. I think the whole IT sphere and the internet is one of the greatest wonders in the entire history of humanity.

After graduation, I went on to the Riga Aviation Institute, in the Programming Department. The institute was situated in Riga, the capital of Latvia, on the Baltic Sea. In the latter years of the USSR (which Latvia was then a part of), the institute was the dream school for programmers, and famous for the quality of its teaching. Admissions were intensely competitive, but I was accepted after my first mathematics exam—my preparation in a specialized high school paying off.

After sunny, dusty Yakutsk, walking the tidy, old streets of Riga under a cloudy sky felt like going abroad. The first time I went shopping there, I saw well-lit shelves filled with numerous varieties of cheese and sour cream, among many other grocery items. Residents of Yakutsk had entirely forgotten what cheese looked like by that point. For the first time in my life, at age 17, I saw yogurt. The only thing you could buy without any trouble in Yakutsk then was canned sardines in tomato sauce. For everything else, you had to stand in line. The line for sour cream and sausage started forming at 5 a.m., despite temperatures of -40 to -50 °C (that’s -50 °F). Fights would break out. People got into MMA-level brawls to defend their spots in line. Say what you like, but socialism or communism, however appealing in theory, don’t suit the reality of people’s egocentric natures. They proved to be less effective than other systems not founded on ideals, but based on competition and a consumer society. The USSR’s 70-year a/b test, if we can call it that, demonstrated that clearly enough.

In the winter of 1991, Latvia, along with the rest of the Baltics, was buzzing, preparing to withdraw from the USSR, peacefully or not. There were barricades up in the old town next to the Riga Cathedral, and people gathering around bonfires on the cobblestone streets, casting long shadows on the walls of the buildings while military helicopters with machine guns flew over the city. Meanwhile, the local attitude toward us, students from the “occupying country,” deteriorated even further. There’s no trace of that nationalism now in Latvia or Estonia, interestingly enough. People are friendly, or, at the very least, neutral—we’re not occupiers now, but tourists.

A year later, when I was a sophomore, Latvia announced its independence, and it stopped paying our stipends. I remember having only dry bouillon cubes to eat all day and setting a trap outside our dorm room windows to catch a pigeon we could fry up. Our attempts were unsuccessful: the pigeons in the former USSR in the ’90s knew quite well what a tasty morsel they were, and they took the necessary precautions to avoid capture.

I had to survive somehow, and so I tried my hand at commerce for the first time: I bought a carton of cigarettes and went out onto the main street of Riga that evening to sell them. But I was soon approached by a group of black marketeers who told me this was their territory, and I had to clear out. When I categorically refused to do so, the police showed up and brought me to the nearest station. They confiscated all my cigarettes and said that, next time, they’d write to the institute, which would mean my immediate expulsion. And so ended my first entrepreneurial efforts.

In Russia, President Yeltsin’s team began their policy of price liberalization, and inflation quickly climbed into the triple digits. My family—my sick mother and my elderly grandmother—were left without anything to live on. My situation wasn’t much better and I then decided to return home to Yakutsk.

Anyone complaining now about the low standard of living on social media from their smartphones while drinking smoothies in trendy cafes and coworking spaces has not lived in the early ’90s in Russia. I distinctly remember sitting in the hallway just after I returned, my head in my hands in despair, wondering how I was going to get money for groceries, how I would be able to feed my family, and coming up with nothing. I remember how happy we were to get the American humanitarian aid my grandmother was issued once: pink canned ham, biscuits, and some other dried rations.

When I finally found work as a programmer in a bank, we joked in the smoking room that the president was so rich he bought a Snickers bar every day. It’s hard to imagine a candy bar being a luxury for even the poorest person today, isn’t it?

At any rate, after my return, I was able to transfer into the math department of Yakutsk University as a full-time student, and get a full-time job at a bank as a programmer, and another part-time job as a programmer in the university’s computer center. I had to do a lot of juggling, but after a month of that, I had resolved our main financial difficulties, and everything gradually went back to normal.

I didn’t find my academic life in this department as engaging as in Riga; the focus here was on higher mathematics, something like functional analysis and differential equations, and very little programming. Moreover, I was already more qualified than my programming instructors, which, in combination with the arrogance of youth, led to a somewhat strained relationship. But mathematics has proven useful to me in work and life, and I don’t regret the time I spent on it. It’s a beautiful discipline, mathematics; the true queen of the sciences, as it is sometimes called. Furthermore, I believe my time in the math department helped me focus on the numbers later, when I was developing my business, and gave me the skills to easily process data, and to see key trends and correlations.

While I was working at the bank, I created a system using the Quattro Pro script language, in the spreadsheet program popular in those years, which analyzed the distribution of the bank’s finances, created nice-looking graphics, and gave recommendations on optimization. The advice was fairly simple; for example, deposits should be made for 91 days instead of 90. This would reduce the Central Bank reserve requirements, which would free up a significant amount of funds for the bank to use. But this was in the early ’90s, when the chaos of newly formed capitalism reigned everywhere, including bank finances, and bankers were in need of even the simplest organizing system. When I realized the potential demand for my system, I left the bank after about a year and a half—everything was set up there and in good working order. Then I began to offer my services as a private consultant to other banks in Yakutsk. Happily for me, there were nearly 30 for a small city with a population of 300,000.

This was how it went. The bored secretary manning the desk in front of the president’s office sees a young man approach: He’s got the look of an intellectual—glasses, wearing a bright green jacket, the latest fashion in the business world. He’s casually carrying a mobile phone the size of a brick, practically unheard of at the time, and the coolest Toshiba laptop. Stammering slightly, he says, “I’m here to see the president regarding the optimization of bank finances using cutting-edge mathematical and computer algorithms.” The secretary, accustomed to the uneducated, rough manners of the local shopkeepers, dreaming of a loan to pay for the next delivery of imported jeans from Turkey or China, would usually get excited and pass on my message right then. The bank president, intrigued, would let this bold young man in and listen to a stream of words consisting of familiar financial terms and unfamiliar computer ones. I’d turn my laptop on (which some of them had never seen before), show them a series of figures, multicolored graphics, and reports. The conversation would end with promises of freeing up additional resources for loans to clients, healthier finances on the whole, and payment only after a positive result. Half of them tossed the young man out on his ear, while the other half decided that, since they had a computer genius in front of them, they might as well give it a try.

I quickly accumulated a portfolio of orders and achieved good results for some of them. They paid me generously in cash. That was the end of my financial difficulties, and I may well have been the wealthiest student in Yakutsk. I graduated from the math department a few years later—the only one in my year to pay for his own education, by the way. The other students presented employment agreements with other institutions, which exempted them from payment.