20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

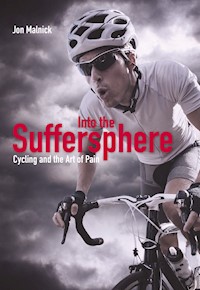

According to the website of The Velominati, the self-professed Keepers of the Cog, the optimal number of bikes owned is n + 1, where n is the number of bikes owned. But there's also an important corollary, s-1, where s is the number of bikes that will cause your wife or partner to leave you.' Into the Suffersphere: Cycling and the Art of Pain is a brilliantly witty account of one former racer's exploration of whether cycling is the one sport that pushes its participants to the very limits of human endurance, and delves painfully into the role that physical and mental suffering can play in this elite endurance sport. Drawing together sporting history and pro-cycling interviews, and investigating current medical, business and psychological theories, this is the story of the extraordinary lengths to which minds and bodies can be pushed. Peppered with recollections from the author's own racing experiences and offering a fascinating insight into the unique allure of pain in a sporting context, Into the Suffersphere explores a side of cycling that you would never have dreamed of - not even in your worst nightmare. An essential read for all MAMILs (middle-aged men in Lycra) and fans of sports writing and smart thinking.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 482

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

In Loving Memory of Richard Malnick,

1937–2015.

Into the

Suffersphere

Cycling and the Art of Pain

Jon Malnick

ROBERT HALE

First published in 2016 by Robert Hale,

an imprint of The Crowood Press Ltd,

Ramsbury, Marlborough Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

www.halebooks.com

This e-book first published in 2016

© Jon Malnick 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7198 2052 6

The right of Jon Malnick to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Contents

1From Marx to Merckx

2The Wheel of Life

3Talent, Transcendence and the Suffersphere

4Passion and Flogging

5Blood, Sweat and Fears

6The Beige Jersey

7Brits and the Four-Year Itch

8Rough Ride

9Mountain Men

10‘If Your Thing Is Gone …’

11Peloton Mindfulness and the Zen of Jens

12Race Hardness

13Race Face and the God of Safety Pins

14Veterans’ Day

15Young at Heart

16Too Close to the Sun

17Bahamontes’ Ghost

18Hamster’s High

19The Middle Way

20Damage and Divinity

Notes

Index

CHAPTER 1

From Marx to Merckx

‘The only antidote to mental suffering is physical pain.’

Karl Marx

I rolled to a halt and staggered off my bike, letting it clatter expensively on to the road. A race vehicle pulled up behind me, headlights ablaze. As I first kneeled, then prostrated myself on the slick cobblestones, I noticed the rain finally had stopped. Then everything faded softly, soundlessly, to black.

I came around a while later, this time laid out in the back of the race ambulance, foggy headed, wondering how long I’d been there and why I wasn’t still on my bike. From the front passenger seat, a uniformed young woman asked me, in what I guessed was Flemish – and, after getting no response, once more in perfect English – how I was feeling. As it happened, I wasn’t feeling too terrible and probably more chipper than anyone who’d just collapsed sideways off his bike in a rain-sodden, Belgian kermesse had any right to feel. Suffering in a bike race was not a big deal. Daily doses of pain and discomfort were par for the course, business as usual. I’d lost count of the times I’d crossed a finish line on the verge of throwing up. If I instead climbed off the bike with a few breaths to spare, with my heart not about to explode out of my chest, I’d berate myself for not having suffered enough. During training rides I often hammered up hills so hard that upon reaching the top my vision tunnelled and I came close to passing out. But this was the first time I’d succeeded in rendering myself completely out for the count.

The longest and toughest bike race in the world, the Tour de France, was founded in 1903 by Henri Desgrange, a bicycle racer turned newspaper editor, who, during his racing career, had claimed a dozen track cycling world records, including the world hour record in 1893. In Desgrange’s estimation, ‘The ideal Tour was a Tour which only one rider would have the necessary power and endeavour to complete.’ For him, simple metrics such as speed or power were not the main concern. Exploring the limits of the human body and pitting man against man and against nature were what got his competitive juices flowing.

Desgrange, a lifelong advocate of strenuous exertion to the point of exhaustion, had witnessed France’s humiliation in the Franco-Prussian war, and believed that his countrymen were ‘tired, without muscle, without character and without willpower’. In the words of a more recent Tour directeur, Jacques Goddet, ‘Desgrange imposed on himself a life of submitting to daily physical exercises. They had to demand, according to his draconian theories, a violent effort, prolonged, repeated, sometimes going as far as pain, demanding tenacity and even a certain stoicism.’ American historian Eugen Weber, the author of a number of wellacclaimed articles on the cultural impact of French sport, believed that the Tour de France played a significant role in early twentieth-century French society. ‘It put flesh on the dry bones of values taught in school but seldom internalized: effort, courage, determination, stoic endurance of pain and even fair play,’ he wrote.1 But if most of the above should be self-evident to anyone with a passing interest in the race, then the issue of fair play has always been more contentious.

Renowned French journalist Albert Londres covered the 1924 Tour for his newspaper Le Petit Parisien, dubbing the fifteen-day race ‘Le Tour de Souffrance’. During the 371km (230-mile) second stage, the previous year’s champion, Henri Pélissier, was penalized for a jersey infraction. Pélissier had ridden off in the pre-dawn chill wearing an extra layer or two, but at some point during the fourteen-hour stage, he discarded a jersey. This contravened race rule no.48, which stated that a rider must finish each stage with everything he had with him at the start. During the next day’s stage, a fraction longer at 405km (252 miles), Pélissier, already not in the sunniest of moods, was accosted by a race official who demanded to know how many jerseys he was wearing. A furious Pélissier then abandoned the Tour as it passed through the town of Coutances, with his brother Francis and another teammate, Maurice Ville, also withdrawing in support. Reporter Albert Londres, himself a keen cyclist and writing for Le Petit Parisien, later tracked down the three riders in a Coutances café, huddled over mugs of hot chocolate. He asked them what had happened.

‘It’s the rules. We not only have to ride like animals, we either freeze or suffocate,’ Pélissier told him. ‘You have no conception what this Tour de France is.’ He went on:

It’s a Calvary. Worse. The road to The Cross has only fourteen stations; ours has fifteen. We suffer from start to finish. You haven’t seen us in the bath after the finish … when we’ve got the mud off, we’re white as a funeral shroud, drained empty by diarrhoea; we pass out in the water. At night, in the bedroom, we can’t sleep, we twitch and dance and jig about like St Vitus.

‘There’s less flesh on our bodies than you’d see on a skeleton,’ offered Francis Pélissier.

‘And our toenails,’ said Henri. ‘I’ve lost six out of ten, they get worn away bit by bit every stage.’

In recounting the suffering of the 1924 Tour de France, Albert Londres coined the phrase ‘Les Forçats de la Route’ (The Convicts of the Road), his choice of words most likely influenced by his visit to the French penal colony in Guyana the previous year – a place he had denounced as a ‘factory churning out misery without rhyme or reason’. A true pioneer of investigative journalism, he also exposed systematic abuse in French lunatic asylums and exploitation of African workers in the colonies of Senegal and the French Congo. For Albert Londres, a man committed to unearthing injustice and suffering wherever he found it, the 1924 Tour offered up a rich vein of opportunity and in the two Pélissier brothers he found himself a pair of willing accomplices. Indeed, Londres’ field reports on the suffering of the Pélissiers, framed in the language of workers’ rights and amplified by France’s communist press, sparked a national debate about the harrowing nature of the race that went on for many years.

‘The day will come when they’ll put lead in our pockets because someone reckons that God made men too light,’ Henri Pélissier told Londres. ‘It’s all going down the chute – soon there’ll only be tramps left, no more artists. The sport has gone haywire, out of control.’

Italian Ottavio Bottecchia eventually prevailed in the 1924 Tour, completing the 5,425km (3,370 miles) wearing an approved number of jerseys and taking over 226 hours to complete the anti-clockwise lap of Western Europe’s largest nation. Most likely to Desgrange’s dismay, another 59 of the 157 starters also managed to finish the race. The 2013 edition of the Tour, one week longer in duration but shorter by 2,000km (1,240 miles), was won by Chris Froome in a fraction under 84 hours.

The modern day Tour de Souffrance may be a somewhat truncated version of its pre-war incarnation, but that’s no guarantee that it’s any less painful. In the 1970 Tour, the great Eddy Merckx briefly lost consciousness after pulverizing his rivals on the torturous climb of Mont Ventoux. Three years prior, Tom Simpson had spent the last agonizing moments of his life grinding his way up the same barren slopes before sliding off his bike and tragically expiring in an amphetamine-fuelled stupor. Irishman Stephen Roche, the 1987 Tour winner, needed emergency oxygen after his legendary fight back against Pedro Delgado on the steep ramps up to La Plagne. As Roche later explained: ‘The doctor puts the oxygen mask on me straight away. “Stephen, move your legs in …” and I can’t move my legs. I can move nothing. He’s trying to put a survival blanket on me, and I can’t move my arms.’2 Television commentator Phil Liggett, for reasons that remain unclear, informs us that ‘Steven Roche is sitting calmly on the floor, he’s okay.’3 At this point, the TV camera zooms in on a fully horizontal, ashen-faced Roche, who appears some way off any generally accepted definition of okay.

At the most rarified levels of cycling, it is this uncommon ability to push beyond run of the mill, race-day suffering, past the quotidian aches, pains and twinges – and occasionally into a state of hypoxic near-oblivion – that suggests winning something like the Tour de France might require not only vastly superior physical attributes, but also an almost superhuman capacity for hurting oneself. It is these world champions and Grand Tour winners, the likes of Merckx and Roche, those who continue to hammer mercilessly where others might ease off the pace, who constitute the revered inner circle of The Great Pantheon of Sufferers.

By definition, only a select few sufferers ever make it into The Great Pantheon. My own less than epic blackout had taken place in light drizzle on top of a smallish bump in Flanders, not at the top of a windswept Alpine peak. And, unlike a Merckx or a Roche, I had not displayed any monumental ability to withstand extreme suffering. Instead, I’d shown the typically wilful stupidity of a nineteen-year-old – a skinny nineteen-year-old attempting to race while under the effects of a chest infection. And attempting to race, it should be said, against the express wishes of my coach, a former national team adviser who had coached top 1980s British professionals such as Paul Sherwen and John Herety. It is by no means easy to fathom the thought processes of my younger self, this aspiring two-wheeled genius, who, upon finding himself fortunate enough to work with a top-tier cycling coach, then proceeded to ignore more or less everything he was told. In hindsight, I’m surprised I ever managed to ride to my local bike shop and back without undergoing a serious health mishap, let alone finish any races.

Yet, week after week, in the glossy pages of the cycling magazines, in the sharply etched details of this or that rider’s pain-wracked raceface, I saw that hurting was part of the game, that there was no glory without suffering and so more suffering surely meant I was more in the game. If I did not return from a ride bedevilled by a certain degree of physical malaise, then I obviously had not trained. Of course, training techniques were much less advanced in those days: no power meters on offer, nor any heart-rate monitors to gauge and record one’s efforts. A simple odometer on the handlebars was considered fairly cutting edge at the time. My taciturn bike coach, Harold ‘H’ Nelson, who had been the Great Britain team masseur at a handful of Olympics and World Championships, and was later awarded the British Empire Medal for services to the sport, would offer the same gruff words of advice after each twenty-minute session on the indoor rollers: ‘Don’t ride home without your hat on.’ By which of course he meant something woolly to keep my head warm. Hard-shell cycling helmets had not been invented yet and the traditional, padded ‘hairnet’ models were rightly viewed with derision. In any case, this woolly hat counsel made excellent sense for anyone braving a wintry Manchester evening and would probably merit inclusion in a modern coaching tome under the heading of ‘marginal gains’, and yet a little more in-depth guidance would not have gone amiss. Perhaps there was, after all, a subtly coded message from ‘H’, one that at least hinted at the importance of measured efforts, at a controlled build-up of intensity, because during the regular roller sessions at his Wythenshawe house, none of his protégés was ever allowed to ride above a steady, midtempo pace. But since training over at H’s place never felt much like what I’d convinced myself was proper training, I compensated by thrashing myself like a lunatic for the remainder of the time I was on my bike.

Michael Hutchinson is Britain’s most successful time-trial racer to date, amassing an astonishing fifty-six national titles over two decades of riding extremely fast. He’s also held competition records at every distance between 10 and 100 miles. In his book Faster, Hutchinson writes: ‘The instinct of most athletes is to train, and train, and train. The single most important job a coach has is to tell you to stop, to take a rest, to recover.’4 Which, in hindsight, and in so many words, is exactly what my coach was telling me, but for some unknown reason I believed I already knew what I was doing. As in fact did the younger Hutchinson, who recalls that before becoming a world-class cyclist, his self-designed training sessions ‘were selected primarily for their unpleasantness and stuffed into an unrelenting weekly schedule until the days bulged at the seams. It may as well have been deliberately designed to blunt as effectively as possible whatever natural ability I’d started with.’5

All of which sounds strangely familiar. After several months of barely registering my coach’s understated yet solid training advice, I finished third in my first race of the season, a hilly circuit race around the Peak District. I was fairly beside myself with this unexpected result. But ‘H’, with typical Mancunian bluntness, seemed less than impressed by my race report. ‘Of course you made it into the breakaway,’ he grunted. ‘But you were in a break of three, and yet you only finished third. Explain what went wrong.’ ‘H’, of course, had reason enough to question my less than stellar tactical nous, to wonder why I’d led my two breakaway companions all the way up the final hill, only for both of them to sprint past me just metres from the line. On reflection I saw how I might have played it better. How I could have played my hand a little closer, instead of excitedly waving my cards at my opponents like a blind-drunk poker player. But developing a decent tactical brain, an ability to read the cat and mouse endgame of a race: this would surely require more experience.

In 1972, the superlative career of Edouard Louis Joseph Merckx reached its glorious zenith. He won the Tour de France, the Giro d’Italia, Milan–San Remo, Liège–Bastogne–Liège, the Giro di Lombardia and a handful of other major events. In August that year he told a journalist he would try to beat the world hour record the following winter. At the Giro del Piemonte in early September, he made a solo attack 60km (37 miles) from the finish; his aim not to win the race, but to practise riding at full power in the same low-profile riding position he would use for the hour record attempt. (But in doing so, he also won the race.) Merckx then embarked on a specific training programme for his record attempt, under the guidance of Dr Ceretelli, an Italian academic considered a leading expert on the body’s adaptation to altitude – where air resistance is lower and straight-line speed is higher. Mexico City was eventually chosen as the preferred location, but the great champion was forced to train at home, in his garage, for the six-week build-up, using a facemask to replicate the effects of Mexico City’s rarified air. As William Fotheringham detailed in Half Man, Half Bike, Merckx took delivery of:

thirty canisters of air with a reduced oxygen content and trained six times a day on static rollers while breathing in the thin air, and with four doctors looking on as he rode. The only glitch came when one of the canisters exploded, injuring one of the doctors and making Merckx believe, for a moment, that his house had blown up.6

Six times a day? I typically managed five or six training sessions per week, all entirely unmonitored by doctors, and I had no idea where I could find oxygen canisters. In my student halls of residence there was a drugged-out first-year student doctor living downstairs from me, who would complain vociferously about the noise whenever I took a spin on my indoor rollers. But in the meantime, with my tactical skills evidently in serious deficit, there was nothing to stop me ramping up my training in preparation for the next race. More suffering surely meant that I was more in the game.

More recently, and during a rare hiatus from road cycling, I would occasionally join a regular weekend mountain-bike ride. A handful of us would flag down a pickup truck taxi to ferry us to the trailhead at the summit of Doi Suthep, the densely forested peak that overlooks my adopted home city of Chiang Mai in northern Thailand. The motorized assistance seemed reasonable enough. Pedalling a heavy mountain bike uphill for well over an hour, along an ever-ascending tarmac ribbon, holds little appeal for the average, sensible cyclist. After quaffing an energizing, locally brewed espresso near the summit, we’d be well primed to plunge back down to the valley floor 1,220m (4,000ft) below, weaving a precarious path through all the rocks, ruts and other obstacles the Trail Gods could throw at us.

All good, dirty fun for this group of certified adrenalin junkies, but there was one small problem. As we stopped to refuel afterwards at a café, my legs would feel absolutely fine. No aching, no soreness; no sense even that the legs had been used and this disquieting sensation, this itch, would linger for the rest of the day. Eventually, I worked out a solution, which was to tackle the route back to front. In my lowest gear, a gear that was never quite low enough, and this time riding solo, I would grind my way methodically up the steep dirt trails, pause briefly at the mountain top for some minor resuscitation, then freewheel down along the graded road back into town. Less fun, more pain, a little lonely and yet somehow more satisfying.

I rarely had any takers to join me on my back to front ride. Which was fair enough, I suppose. Most would prefer that their weekend mornings fit loosely into the general category of ‘recreation’, which for the Oxford Dictionary is an ‘activity done for enjoyment when one is not working’. Yet at some point – and it remains a little unclear at exactly which point – some of us seem to foment within ourselves a curious, nagging need for precisely this kind of painful work. We start coveting it, craving it, almost as if a hospital X-ray exam might reveal the existence of a suffer-shaped hole somewhere deep inside. We try to assure ourselves that there’s nothing inherently wrong with this, with seeking out bodily suffering for the calming sense of spiritual purification that follows. It all has much in common with scratching a stubborn itch. The more you scratch, the more you itch.

CHAPTER 2

The Wheel of Life

‘There are times when I wish I hadn’t won the Tour de France.’

Bradley Wiggins7

During the final mountain stage of the 1956 Tour de France, Federico Bahamontes, the Spanish rider recently voted the best climber in the race’s history, found himself dropped early on by his great rival, Charly Gaul. ‘The Angel’ had got one over on ‘The Eagle’, as cycling archivists might have it. During the climb of the Col de Luitel, ‘The Eagle’ Bahamontes was reportedly ‘overcome by bad morale’. Grinding to a halt halfway up the mountain, Bahamontes duly stepped off his bike and tossed it into a handily situated ravine. But the mental fog resulting from Bahamontes’ swift onset of anguish evidently prompted him to make a poor choice of ravine, as his team helpers were able to scramble down and retrieve his bike. Bahamontes remounted and finished the stage in fourth place.

Bike racers clearly know a thing or two about the art of suffering. But history reveals that a longish list of non-bike racers, those everyday folk otherwise known as the general public, have also staked claims to authentic experiences of suffering. Many have insisted on having their own say on the matter, all too often with mind-numbing prolixity. The nineteenth-century German philosophers made a decent name for themselves writing impassioned and largely unreadable analyses of suffering and the meaning of existence. As one Friedrich Nietzsche liked to say to his friends, ‘To live is to suffer’. But the Germans, despite a laudable collective effort, were by no means the first to get serious on the thorny topic of suffering. The Buddhists got there first.

Their story begins a little over 2,500 years ago with a young Siddhartha Gautama, who whiled away a quiet month or two lounging under a Bodhi tree – a large and sacred fig tree – in northern India. In a possible attempt to justify his anti-social, work-shy behaviour, he then claimed to have become enlightened as to the true causes of existential suffering. Remarkably, his observations were entirely focused on the universal human condition and not on remedies for insect bites or a stiff lower back. These discoveries later became enshrined as the so-called Four Noble Truths, upon which the founding principles of Buddhism are based.

The Noble Truths attempt to explain the essence of our earthly suffering, the various causes of such suffering and how we may ultimately overcome them. The language used in many of the early texts was Pali, a direct descendant of Sanskrit and believed to be a lingua franca for the many Indo-Aryan dialects spoken at the time in the Indian subcontinent. While the word ‘suffering’ is probably the closest English translation to describe what was vexing the Buddha in his pre-enlightened mode, it’s actually a little too restrictive. While our prototypical Buddhists also gave serious thought to related themes such as anxiety, frustration and stress, our modern understanding of these all too human conditions inevitably skims over the deeper, essentially metaphysical meaning of the Noble Truths. In illustrating the painful and mostly unreliable nature of wide swathes of human existence, the early Pali transcripts make frequent reference to a state known as dukkha, a concept that encompasses not only plain old physical and mental suffering, but also what might be termed the ‘basic unsatisfactoriness of all things’.

This gives us a useful reference point, namely that in the approximate period between birth and death, there is considerable scope for disappointment and disaster – which handily sums up our First Noble Truth. Of course, this might all come across as rather gloomy: universal suffering is to be our lot in life, now go away and deal with it. Yet your average Buddhist still prefers to believe that his or her take on existence is one of realism and objectivity, not abject pessimism. Herein lies the Second Truth, which tells us that dissatisfaction is largely a choice, merely the result of an enfeebled state of mind; that our constant craving for satisfaction every step of the way amounts to a base ignorance of the true nature of things. A little more cheerily, the Third Truth explains that only after we fully grasp the complete folly of our human condition, our foolish cravings and aversions, can we then free ourselves from the torment of endless suffering, the repeating cycle of birth, life and death known as samsara.

Sir Bradley Wiggins may well look back upon 2013 as the year of his descent into dukkha. Certainly it was an annus horribilis. Perhaps the loquacious Londoner would more typically sum it up as a ‘pile of crap’ – which, as any enlightened soul knows, amounts to more or less the same thing. This would have been nigh on impossible to predict a year earlier when Wiggins won the Tour de France – the first Briton ever to do so – and then claimed Olympic time-trial gold, all within the space of a few weeks. With many commentators hailing him as the best British sportsman of all time, Wiggins said: ‘I don’t think my sporting career will ever top this. That’s it. It will never, never get better than that.’8

Ah, Bradley. Although not to my knowledge a practising Buddhist, Wiggo here does seem au fait with the vicissitudes of life, the suffering of impermanence, of what Buddhists call viparinama-dukkha. As regal and imposing as he’d looked on his Hampton Court throne following his 2012 Olympic time-trial victory, Wiggins’ annus mirabilis had come dangerously close to collapse just a few weeks earlier. On stage eleven of the Tour de France, Wiggins, already resplendent in yellow and with a two-minute lead overall, was so incensed by an unscripted mountain-top attack from his teammate, Chris Froome, that he later sent the Team Sky managers a text message that read: ‘I think it would be better for everyone if I went home.’9

When even the triumph of a Grand Tour win comes bundled with frustration and irritation, it’s then not hard to understand the appeal of the Buddhists’ all-revealing Fourth Truth, ‘The Path to the Cessation of Dukkha’. Imagine if you will a set of detailed instructions on how best to achieve a more suffer-free existence, a kind of antiquarian self-help manual. This prescriptive tonic, more properly known as ‘The Noble Eightfold Path’, and which forms the foundation of all Buddhist philosophy, might have even become an early bestseller had it not made its appearance well over a thousand years before the world’s first printing press. Buddha & Co. therefore had to make do with word of mouth, offering up their newly found wisdom to all as they strolled around the Indian countryside on what amounted to an ongoing national tour. Tough work for sure, even if the annual monsoon season, which made travel virtually impossible, allowed the monks some well-deserved downtime each year.

Early Buddhists did not have bicycles. After all, the velocipede, the shortlived precursor to the bicycle, did not make its first appearance until the early nineteenth century – an oddly late arrival in evolutionary terms, considering that more complex machines such as steam engines were by then widely in use. But Buddhists certainly had wheels. The Iron Age was in full swing by the time Lord Buddha was wandering around lecturing the public on his Truths. Iron smelting was widespread in India as early as 1,000bc and so during the Buddha’s lifetime several centuries later, the Iron Age would have been well into its high-tech phase. Wrought-iron wheels were hammered into shape for all manner of carts, wagons and chariots. The idea of fitting spokes to wheels, usually made from wood to produce lighter and faster vehicles, had been around since as early as 2,000bc. Basic wheel design in fact did not change much over the next couple of millennia, not until the advent of the rubber tyre opened up a new realm of possibilities.

The ancient Aryans who brought the Sanskrit language to India were a nomadic tribe who did most of their travelling in ox-drawn vehicles. In classical Sanskrit, du is a prefix that denotes ‘bad’, while kha was originally the term for an aperture, or a hole, and specifically an axle hole for a vehicle. Many scholars believe the correct etymology of dukkha is that of a poor-fitting axle hole, one that causes discomfort for the vehicle’s occupants. Another variant of dukkha in Sanskrit was that of a potter’s wheel that would not turn smoothly. Various other Buddhist cultures have used similar terminology; in China, dukkha goes by the name of k, signifying a broken or irregular wheel that gives the rider a jolt on each revolution – a sensation not unfamiliar to many amateur racers who have unwisely splashed their hard-earned cash on a pair of cut-price carbon wheels, most probably made in China, and probably not built to last. Similarly, we have ku in Japanese, ko in Korean and kh in Vietnamese.

On a winter training ride in early 2013, the newly knighted Sir Wiggins sustained a nasty jolt in the form of several broken ribs when possibly the UK’s most hapless van driver unwittingly knocked him off his bike. Wiggins recovered well enough to start the 2013 Giro d’Italia as the pre-race favorite, but then came down with a heavy head cold, a chest infection, and – following a crash early in the race – a serious loss of confidence on the descents, admittedly on roads that were often slick from atrocious, unseasonal weather. To add insult to dukkha, Wiggins suffered a slow puncture during the Giro’s individual time trial, a stage he was under some pressure to win. Television coverage showed him hurling his Pinarello time-trial machine off the road (no handy ravine this time), his frustration all too evident as he awaited a spare bike.

After abandoning the Giro on stage twelve, Wiggins then pulled out of the 2013 Tour de France a week before the start in Corsica. Whatever narratives were offered up to explain Wiggins’ non-participation, the plain truth was that Chris Froome, teammate if not exactly best mate, was a stronger candidate to challenge for the 2013 Tour. Froome duly obliged by reaching Paris in yellow and with the biggest winning margin for sixteen years. After Froome’s triumph, Wiggins explained to reporters: ‘I didn’t watch it – I couldn’t watch it.… I followed it from afar, but it was too painful to watch.’10

A year earlier, Wiggins had spoken at length about the extreme sacrifices involved in preparing for the Tour de France – the six-hour training rides each day, then bedding down for the night in a hermetically sealed oxygen tent; the monotony of living on top of a volcano in the middle of nowhere and the long months away from his wife and kids. Training for the Tour involves suffering. Winning the Tour calls for more of the same. But despite putting in the graft, all the pre-suffering, Wiggins then found himself, at the eleventh hour, demoted to the role of race spectator for the 2013 Tour. While he could have followed the race from the comfort of home, he chose not to, admitting he would have become ‘depressed’ if he had. The last time Wiggins had watched the race from the sidelines had been back in 2011, after he’d crashed out on stage seven with a broken collarbone. But was Wiggins’ devastation at missing out on the 2013 Tour a still more painful experience, an unwelcome, supersize serving of dukkha?

Bradley’s calamitous 2013 might have taken him by surprise, but it’s worth noting that in the Eastern Hemisphere at least, this powerful association between wheels and suffering, between rotational mass and dissatisfaction, dates back more than two millennia. Buddhist philosophy likewise attaches strong symbolism to the simple wheel. The Dharmachakra, or ‘Wheel of Life’, is recognized globally as a symbol of Buddhism. It also happens to be the emblem at the centre of the Indian flag. In 1921, Mahatma Gandhi proposed a flag with a traditional spinning wheel at its centre, to symbolize his desire that Indians become self-sufficient by making their own clothing. But only days before the country’s independence in 1947, India’s National Assembly instead decided that the flag’s emblem should be the Ashoka Chakra, a variant of the Dharmachakra.

The Wheel of Life is widely depicted in Buddhist art and iconography. It appears in many sizes and with different spoke options, as of course do bicycle wheels. Typically, the Dharmachakra’s hub denotes discipline, the essential core of meditation practice. The wheel’s rim, holding all the laws (spokes) together, signifies mindfulness. Dharma wheels variously appear with twelve spokes or twenty-four spokes. There’s even an asymmetric option consisting of thirty-one spokes. But the eight-spoke wheel representing The Noble Eightfold Path is the most common configuration. Whereas an eight-spoke bicycle wheel would be a fairly specialized, race-specific affair and certainly not one recommended for everyday use, the wheel denoting The Noble Eightfold Path – the path to self-awakening and liberation from endless dukkha – is a must-have item in any Buddhist kitbag.

For those of us who like to believe we’ve achieved at least a modicum of self-awakening, there is always the possibility that bike rides can be enjoyable on occasion, not merely a litany of disappointment and disaster – or nothing but unadulterated dukkha, in short. Riding a bike can be fun. Should be fun. While many have made a decent living out of despairing of the future of the human race, it’s the Buddhists, with their time-honoured formulae for micro-managing despair, for minimizing suffering, who will tell you that most aspects of life can in fact be joyful if approached with the right mindset. That once we’ve accepted the general unsatisfactoriness of just about everything, there is plenty of satisfaction to be found, if only we knew where to look. Of course, the Buddhists’ deadly simple solution to this exhausting quest for satisfaction, or happiness, or joy, or call it what you will, is to not go looking for it in the first place. ‘Ask yourself whether you are happy, and you cease to be so,’ John Stuart Mill concluded some years ago.11 He was surely barking up the right tree, even barking up a Bodhi tree, but for us blithely to avoid asking the question altogether seems a pretty big ask in itself.

Buddhist gurus also stress the critical importance of a healthy sense of humour as we fumble our way through life and three-week bicycle races. The Dalai Lama himself has an infectious giggle and a well-documented fondness for practical jokes. But the biggest Buddhist joke of all is that most of us seem trapped in endless pursuit of something that’s right in front us of. It’s like ransacking the entire house in search of the car keys already stuffed inside your pocket. ‘Our state of mind is crucial in determining whether or not we gain joy and happiness,’ the Dalai Lama says. ‘So leaving aside the perspective of Dharma practice, even in worldly terms, in terms of our enjoying a happy day-to-day existence, the greater the level of calmness of our mind, the greater our peace of mind, and the greater our ability to enjoy a happy and joyful life.’12

The quest for a happy and joyful life is a task perhaps best left to the professionals. But a happy and joyful hour or two on a bicycle: this is surely something well within our grasp. ‘Just mount a bicycle and go out for a spin down the road, without thought on anything but the ride you are taking,’ as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle waxed. Yes indeed. Surely that’s why any of us hop on a bike in the first instance? We learn to ride as kids. It’s the uncomplicated, unalloyed joy of trundling around the garden or the local park on your first toddler tricycle. And, really, what a life it is, to be three years old and on the move, travelling under your own steam. Here’s yet another liberating, enfranchising form of self-propelled forward motion, and coming so soon after the frankly miraculous discovery that you can use your wobbly little legs for walking around. True, your miniature contraption probably doesn’t have pedals, or a chain, and certainly no gears. In technical terms it’s actually not even a bike, it’s merely a stripped-down imitation of a bicycle. But over time we graduate to a bike proper and to the challenge of learning to stay upright on only two wheels – which as anyone who’s ever spent time in the middle of a peloton will be well aware, is a technique that some never quite master.

George Hincapie, Lance Armstrong’s most trusted lieutenant over the years, had his signature way of announcing when feeling especially happy and joyful on the bike. He’d ride up alongside a teammate, a wide grin on his face, and declare: ‘I don’t feel a chain. Is there a chain on my bike?’ Hincapie was alluding to the sense of sublime ease and serenity we feel on those days when bike and body are in perfect sync: when both are well tuned and oiled, when the cranks spin freely and the legs are supple. In French, la souplesse refers to the act of executing any physical movement as smoothly as possible. In cycle sport, it remains the gold standard, a means of judging whether riders exhibit a decent style, if their form on the bike is pleasing to the eye. Some appear to be blessed with natural souplesse: the likes of present-day champions Alberto Contador and Vincenzo Nibali, for example. Other professionals habitually come across as if they’re trying to strangle their handlebars: Tommy Voeckler and Chris Anker Sørenson spring to mind here. What Mr Hincapie was not alluding to of course was the fact that much of his apparent chainlessness, his low-friction aura of feel-good, might have had to do with a few ‘supplements’ administered earlier by his team doctor, but at this point that’s neither here nor there.

The point is that those splendid, gently backlit, tail-winded days on the bike do occur from time to time – interspersed of course between extended spells of dukkha – and whenever they do, there’s really nowhere else you’d rather be. The Buddhists have long recognized this. For as much as we are unable to escape the general pervasiveness of dukkha, when the alternative does present itself, why indeed not bask and wallow – like a hippo in a low veldt mud pool – in some joy, in pleasure, in a sense of satisfaction and ease? In the ancient Pali language, the antonym of dukkha is sukha. The etymology is essentially the same: by simply changing the prefix from du to su – by substituting ‘good’ for ‘bad’ – our previously stiff, jammed-up wheel axle changes into one that ‘runs easily or swiftly’, according to the Rig Veda, one of the canonical texts of Hinduism. In the Pali literature, the term sukha denotes the idea of ease and flow and, by association, a sense of pleasure, happiness or bliss.

Cycle-specific sukha may lack a precise dictionary definition, but we know it well enough when we feel it. When wheel rims run smooth and true. Saddles and backsides remain in good accord, in an entente cordiale. Brakes engage without squeak or squeal. Gear shifts become effortless and precise. The recent introduction of electronic gear shifting has been even hailed as a step towards cycling nirvana. And it can be, most of the time, at least until you forget to charge the shifters’ onboard battery. In this instance, you will find yourself stuck in a horribly over-geared samsara all the way home. A rebirth as a more enlightened being that better appreciates the importance of battery charging is, however, always possible.

A chain is indeed present on these sukha-filled halcyon days, but it remains unsung and unassuming. Bicycle chains, like small children, are best seen and not heard. Cranks and pedals spin away merrily with no creak or click. It turns out this last point is actually fairly crucial. Because however wonderful a time you’re having on the bike, however joyful your ride may be, the first hint of any irregularity, of the slightest commotion or disturbance from the vicinity of the drivetrain, and it’s basically all over. Nothing deflates a sense of bike-bound bliss faster than the sound of components feuding with each other – especially a sound that repeats itself on each pedal stroke. It is the bicycling equivalent of Chinese water torture. And here I could outpour an entire chapter on the unadulterated, misery-inducing dukkha of the new press-fit bottom bracket assemblies, but I’ll restrain myself.

For Bradley Wiggins, as 2014 rolled around, it seemed that his unbidden bout of dukkha had not quite run its course. He appeared somehow adrift, in a curious state of limbo. He had a crack at the Paris–Roubaix classic, finishing a creditable ninth. But Christopher Froome was by now established as Sky’s preferred leader for stage races, with team boss Dave Brailsford clearly intent on scheduling separate race programmes for his two feuding team members. Wiggins took a comfortable victory at the Tour of California, but despite stating his willingness to ride in support of Froome at the 2014 Tour, he was omitted from the ten-man selection and consigned to once again spending much of the month of July on his sofa, semi-submerged under a stack of cushions and stealing sidelong glances at the television.

As sporting dethronements go, this was fairly grim. While British cyclists such as Chris Hoy or Mark Cavendish have garnered more outright race wins, the breadth of Wiggins’ achievements on the bike is unparalleled. To win a Tour de France, on top of Olympic gold in the individual pursuit and the road time trial, requires dominance at events lasting variously four minutes, one hour and three weeks. Not even Merckx managed this. An equivalent achievement in athletics might be to win the 100m, the 1,500m and the marathon. When double Olympic champion Mo Farah recently switched to the marathon after proving almost unbeatable at 5,000m and 10,000m, many felt it was a risky move and Farah has struggled thus far at the longer distance.

But here was brave Sir Wiggo, one of the world’s most accomplished bike riders, and yet all of a sudden only semi-employed – certainly a highly lucrative form of part-time employment, one that the rest of us would jump at, but still. Further Grand Tour exploits appeared unlikely. A return to his track roots seemed probable and a move to a new team was even mooted, preferably one without a gangly, balding Anglo-Kenyan at the helm. But this is dukkha. This is the naked truth of impermanence. This is exactly what the Buddhists are on about. One minute you’re on top of the world, perched splendidly upon your Olympic throne, or at the very least on a swivel chair in a large corner office, then before you’ve even had a chance to take it all in, the viparinama viper rears up and nips you on the backside.

And for a wistful Sir Wiggo, it was not simply a case of grappling with the truth of impermanence, but also with the inevitable dissatisfaction of things – even those things we’d thought would most satisfy us:

You can plan physically to try to win the Tour but I could never plan for what was going to happen after it. It just went mad for a bit. Looking back now you don’t fully appreciate it at the time, you just try to take it in your stride … and drinking and stuff to try to ease your way through it. It was massive really. I can’t really put it into words how much it changed everything.13

To Wiggins’ credit, he managed to refocus his efforts back on to the track – the source of his early success – and within weeks had grabbed a silver medal in the 2014 Commonwealth Games team pursuit. He confirmed that further Grand Tour exploits were off the agenda, with the 2016 Rio Olympics now the principal target. ‘The last six or seven weeks since I’ve been back on the track have just been really refreshing and a good distraction from all of that Tour de France nonsense,’ a newly bearded and bulkier Wiggins told the Guardian. In early 2015, he confirmed his forthcoming retirement from the road scene, targeting one final attempt at Paris–Roubaix. With Rio 2016 locked in the sights, the former Tour winner will be the spearhead for the eponymous ‘Team Wiggins’, a new, Sky-funded elite squad. ‘It’s given me another focus rather than just lolling about at home feeling miserable.’14

Of course, had sofa-bound Bradley peered above his cushions for long enough to catch the early stages of the 2014 Tour, he would have watched an upended Chris Froome crash painfully on various sections of France’s northernmost highways – not once, not twice, but three times, all within a 24-hour period. If the first cut wasn’t the deepest, it still shredded the left side of Froome’s shorts and stripped away several layers of his skin. Froome at least managed to fall to his right for the second chute, but after sliding off his bike a third time barely an hour later – and this before even reaching the stage’s treacherous cobbled sections – enough was clearly enough. A soggy Froome, face set to impassive, handed over his bike to a Sky helper and folded his lacerated limbs into the backseat of the team Jaguar. A hospital X-ray scan found he’d broken bones in his left wrist and right hand.

Only hours before Froome abandoned the 2014 Tour somewhere outside of a rain-sodden Ypres, his much anticipated title defence over before even turning a pedal in anger, millions – or more accurately billions – had watched Germany trounce Brazil 7–1 in the FIFA World Cup semi-final. This amounted to a truly shocking fall from grace for the Seleção Brasileira, a collapse that had journalists worldwide scratching their heads, wondering if we’d witnessed the greatest single sporting surrender of all time. It felt entirely reasonable to believe that whichever karmic deity was on duty that week for major sports events, cranking those weighty, cast-iron levers of fate and fortune, he was certainly having great fun on the job.

CHAPTER 3

Talent, Transcendence and the Suffersphere

‘What is talent, really? Is it the fact that your heart pumps more volume than the average person’s or that your blood turns less acidic when exercising? No, talent has to do with your capacity for suffering.’

Eddy Merckx

A twelve-year-old Bradley Wiggins informed his art teacher that he planned to win the Tour de France one day. ‘My art teacher at school, St Augustine’s in Kilburn, dragged me to one side and asked me: “What are you going to do with the rest of your life Bradley? You can’t go through it like this,’” Wiggins told the BBC. ‘I said “I want to wear the yellow jersey and win an Olympic gold medal” and she said “that’s crazy”, because how many kids from Kilburn did that?’15

At the age of fifteen – around the same time that a two-year-old Bradley was learning to walk – I’d certainly heard of the Tour de France, but had no great desire to take part in it, or any other bicycle race for that matter. I had though just completed my first ever long-distance ride, 60 miles from London to Brighton, aboard my new twelve-speed Raleigh. For reasons I can no longer recall, I’d convinced myself that tennis shoes and a pair of bootleg Levi jeans were perfectly functional items of cycle wear and that a packet of crisps every 5 miles or so represented optimal nutrition for endurance events.

My pale green Raleigh Rapide was much admired and ogled; she was for a short while the pouting starlet of the school bike shed. But almost overnight there appeared a usurper, a thoroughbred race machine with far more sumptuous lines and curves: Columbus superlight tubing; metallic blue with chromed forks and stays; full Campagnolo accoutrements; and dark grey anodized Mavic rims. This was ultimate bike porn, circa 1983. The bike’s owner, a pint-sized, bespectacled Singaporean called Andrew Lim, was even a member of a local cycling club. There’s a scene in many a Hollywood movie where decent but average kid first espies the shimmering beauty of the leader of the school cheerleading squad: aching, unconsummated desire. But at our school there were sadly no girls to espy, let alone cheerleaders. Andrew’s bike was by far the loveliest thing I’d ever seen. It left me weak at the knees. In comparison, my bike was just a heap of metal.

With somewhat Machiavellian motives I befriended Andrew and soon became privy to his major plans for the coming season. ‘Must train. Train hard every day,’ said Andrew. Would it be possible, I asked, to maybe join him on a ride? Andrew cautioned that not all of us were cut out for hard training, but he nodded his assent and on a wintry morning, both of us wrapped in several layers of wool and lycra, we threaded our way through the high streets of suburban North London towards the quieter lanes of Hertfordshire. But barely 5 miles into the ride, at the foot of Barnet Hill, Andrew was wavering. ‘Actually is quite cold today,’ he said. ‘And windy.’ I signalled my agreement. ‘Actually not good to ride in condition such like this one. We must turn back.’ Turn back we did. Follow-up training rides with Andrew never quite materialized: it wasn’t always the weather, but it was always something. I soon worked out it was feasible to train alone and that it might be worth searching for a new mentor. Andrew later agreed to sell me his gorgeous bike, but then mysteriously returned to Singapore before a deal could be struck.

With his homewards U-turn, the owner of north London’s sexiest bike was ignoring the plain fact that the current incumbents over at The Great Pantheon – Hinault, Fignon, Kelly – were out on their bikes in all conditions, even cold, windy ones. Irishman Kelly typically thrived in atrocious weather. And besides which, training – hard training in single-digit temperatures – while a prerequisite for success, is not in itself sufficient. Had the diminutive Lim managed to train as hard on the road as he’d planned inside his own head, he was still never going to win the Tour de France, nor even gain selection to carry water bottles for a Tour de France winner. Nor was I of course. Barring the way stands the minor issue of exceptionality.

Only a very small percentage of athletes, by definition, can be considered exceptional. In bike racing as with many other sports, it is not always obvious just how much exceptionality is required at the uppermost levels. As an example, a decent club cyclist might be able to average 40km/h (25mph) over a one-hour time trial. At first glance, that might look within acceptable range of world time-trial champion Wiggins, who typically averages 48km/h (30mph) or so on a flat course. After all, what’s a mere 8km/h (5mph)? That’s barely the pace of a leisurely weekend jogger, shuffling his way around the local park. But an alarmingly non-linear relationship between speed and power output means that travelling at warp factor, Wiggins requires around 80 per cent more lung and leg power than even a reasonably well-conditioned club rider puts out. Or suppose instead that three untrained but otherwise able-bodied blokes turn up on a triple tandem for a head(s)-to-head against Sir Wiggo. Their combined power output might just about match that of Wiggins, but due to all the extra weight and wind resistance, they still won’t go as fast. Put another way, an amateur who improves his power output by only 10 per cent can transform himself from mid-peloton finisher to outright winner. Any pro rider who conjures up a similar improvement in performance will find himself fielding tricky questions from the doping agencies.

How you get to be exceptional is an area of endless debate. There’s author Malcolm Gladwell’s popular 10,000-hour maxim, 10,000 being the approximate hours of practice believed necessary to become world class in almost any discipline, whether it’s pro sports, brain surgery or the performing arts. In a similar vein, Matthew Syed’s recent book Bounce espouses the power of practice over the ‘myth’ of talent.16 Syed argues that with enough determination and dedication, almost anyone can reach the top of their chosen field. But this theory works better for, say, table tennis – Syed is an ex-England international – than for an endurance sport like cycling. For table tennis players, the critical skill of hand–eye coordination is honed through years of daily practice. And while they undoubtedly need to be in decent physical shape, few, if any, table tennis champs have ever needed extra oxygen in the aftermath of a gruelling finale.

In contrast, cycling performance from a purely physiological standpoint is highly dependent upon a few key markers. Five times Tour de France winner Miguel Indurain had a reported maximal oxygen uptake (VO2 max) of 88ml/kg. More simply, his lung capacity was about double that of an average, non-athletic male. While training can increase VO2 max to a limited extent, a less naturally gifted rider might train diligently for years and still not score a VO2 max much above 60ml/kg. Another important metric is that of lactate threshold, the point at which lactic acid and other waste products start to accumulate in the bloodstream during intense exercise. Two of the highest lactate thresholds ever recorded in up and coming riders? Lance Armstrong and Alberto Contador.

Raw talent, however defined, may not be the only component for success, but it certainly helps. Two times Tour de France winner Laurent Fignon switched from football to cycling at the age of fifteen and was promptly told that he had left it too late to succeed on the bike. His parents also disapproved of cycling, so he would sneak out of the house to go for training rides. All of which mattered little: talent will out. In Fignon’s first race, he attacked alone from a field of sixty or so and won by almost a minute. Indeed, most pros can recount similarly gilded tales of their initiation into racing. George Hincapie, who completed seventeen Tours de France, was wiping the floor at his local under-sixteen races at the tender age of twelve.

At roughly the same age as Fignon, I finished ninety-eighth in my first bicycle race, over ten minutes behind the winner. My parents did not exactly disapprove of bike racing; I think they assumed that wearing colourful lycra was a strange form of teenage rebellion. My mother’s puzzled indifference to my chosen sport switched to mild concern when, a few months later, I started shaving my legs. The cool factor, the overall hip quotient of cycling, may have increased exponentially in recent years, but in early 1980s Britain, it barely even registered as a recognized sporting activity. I would have been no further from the mainstream if I’d taken up curling or clay pigeon shooting. As one of my mother’s friends told me recently: ‘We always wondered if there was something wrong with you.’

Since claiming that coveted top 100 spot in my first event, I’ve raced bikes on and off over several decades across several different continents. I’ve won my fair share of races, have come within a shout of winning a few more and finished well down the field in countless others – almost always with a sense that I could have, should have, done better. And yet, as a neophyte rider with a few decent results tucked away, it’s all too easy to start entertaining delusions of cycling grandeur. But it is a fragile, precarious delusion and one that is unlikely to withstand a close encounter with genuine talent. I can recall my slack-jawed astonishment as a junior rider when the existing national champion came thundering past me in a time trial – astonishment not so much that I was being overtaken, but that any human being could propel a bike forwards with such violent force and intensity. But if natural talent on a bike is a slippery concept to define, identifying talent is comparatively straightforward, particularly when it comes hurtling past you at full tilt, or, in a marginally less humbling scenario, when you’re busting a lung trying to hang on to its back wheel.

These days, I occasionally join a weekend group ride comprised mainly of other middle-aged men in Lycra, also known affectionately by their acronym, MAMIL. Market-research company Mintel coined the now ubiquitous phrase back in 2010. Its report found that the MAMIL demographic was mostly comprised of socioeconomic groups A and B, earned decent incomes and read broadsheet newspapers. Said purchasing power would buy them their choice of high-end bicycle (or bicycles), prolevel machines typically priced at several thousand pounds apiece. And MAMILs are, by definition, exclusively male. As a BBC report noted: ‘Flashy sports cars are out, now no mid-life crisis is complete without a souped-up road bike.’17