Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

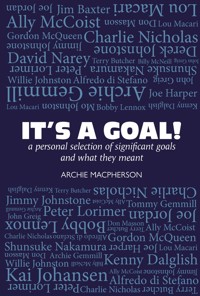

The scoring of a goal in football unleashes emotions for the scorer, teammates, opponents and onlookers on terracing and living-room couches, that can play havoc with our anticipation of what constitutes an ordinary day. Legendary commentator Archie Macpherson delves into the heart of the beautiful game, where the simple act of scoring a goal becomes a profound moment of human connection. From the roar of victory to the sting of defeat, Macpherson captures the essence of football's emotional rollercoaster through a curated personal selection of significant goals – some spectacular, some less-so, some not-at-all, but all significant – together with the fascinating backstory to each goal and the match in which it was scored. With unparalleled insight and passion, Macpherson invites readers to experience the highs and lows of football, a game where so often a goal transcends the boundaries of the pitch to touch the hearts of fans worldwide. It's a Goal! is a testament to the enduring power of football to unite, inspire and move us all – whoever our team, wherever we are.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 322

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ARCHIE MACPHERSON was born and raised in Shettleston in the eastend of Glasgow. He was headteacher of Swinton School, Lanarkshire, before he began his broadcasting career at the BBC in 1962. It was here that he became the principal commentator and presenter on Sportscene. He has since worked with STV, Eurosport, Talksport, Radio Clyde and Setanta. He has commentated on various key sporting events including three Olympic Games and six FIFA World Cups. In 2005 he received a Scottish BAFTA for special contribution to Scottish broadcasting and was inducted into Scottish football’s Hall of Fame in 2017.

By the same author:

Touching the Heights: Personal Portraits of Scottish Sporting Greats, Luath Press, 2022

More Than A Game: Living with the Old Firm 2020 Luath Press

Adventures in the Golden Age: Scotland in the World Cup Finals 1974–1998, Black and White Publishing, 2018

Silent Thunder, Ringwood Publishing, 2014

Jock Stein: The Definitive Biography, Racing Post Books, 2014

Undefeated: The Life and Times of Jimmy Johnstone, Celtic FC, 2010

A Game of Two Halves: The Autobiography, Black and White Publishing, 2009

Flower of Scotland?: A Scottish Football Odyssey, Highdown, 2005

Action Replays, Chapmans Publishers, 1991

The Great Derbies: Blue and Green, Rangers Versus Celtic, BBC Books, 1989

First published 2024

ISBN: 978-1-804251-39-3

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

Typeset in 11.5 point Sabon by

Main Point Books, Edinburgh

© Archie Macpherson 2024

Dedicated to Pat Woods

Contents

Introduction

1. The First Hurrah

2. Local Hero

3. Tribalism

4. Starstruck

5. Pars for the Course

6. Auditioning

7. In at the Death

8. Nobody Does It Better

9. A Winning Head

10. End of an Era

11. Decimal Points

12. An Italian Dessert

13. Camera Chaos

14. A Foreign Foot

15. The Narrow Margin

16. The Breakthrough

17. World Beaters

18. Guid Gear

19. The Peak

20. Granite Approach

21. Full House

22. The Miscalculation

23. Teenage Debut

24. How to Burst a Coupon

25. One Crowded Spanish Evening

26. Studs to the Fore

27. Arthur’s Warning

28. Drawing a Line

29. Sassenach Intervention

30. The First Hiccup

31. The Odd Couple

32. Raising the Temperature

33. A New Kind of Pain

34. Breaking the Mould

35. The Finest Touch

36. A Political Stew

37. Delusion

38. Hanging by a Thread

39. Breakdown

40. The Immortal Touch

41. Stunning Finale

42. Sipping Success

43. Crowded Out

44. A Likely Lad

45. The Tartan Rebirth

46. That Memorable Hug

47. Withering Words

48. The Saddest Night

49. Heartache

50. The Crumb of Comfort

51. The English Accent

52. The Pyrrhic Victory

53. Topsy Turvy

54. A Sending Off

55. Mishap

56. Sayonara Spectacle

57. The End of the Affair

Acknowledgements

Introduction

GOALS SEEMED TO choreograph my life. Charged with the duty of commentating on football matches for nearly half a century, they seemed to route me through the passage of time. The significant ones stand erect like landmarks without which I could not look back on life with as much sense of order and the appreciation of one age merging into another. These included startling expulsions of my breath in World and European Cups as well as domestic football back to the days when I would stand and watch junior football as a boy readily infatuated with this marvellous sport on my doorstep. Not all the goals that lodged in the mind, never to be cast asunder, were spectacular. And some may even think my selection eccentric given that it is a very personal reflection of how I was affected by specific goals that may not have raised an eyebrow for others. They are MY goals, lodged within me for one reason or the other, lending a particular interpretation to a game that would particularly separate it from others. They also revive my recollections of the personality clashes and the political infighting that characterised so much of my time in this business. So, in every reminiscence there is a goal and scorer whom I list singly, and who makes me appreciate how privileged I was, not only to be a witness to these events but as a voice harmonising with them to perpetuate their significance.

Of course, I had the utmost admiration for the creative geniuses of football without whom goals would never have been scored. But a goalless game, whatever elegance and skill might have abounded throughout, I treated like a tasteless meal lacking these imperative condiments of flavour that separated victor from vanquished. I was also fortunate to have worked throughout a period which saw me experience six World Cups and was present when three Scottish clubs returned to these shores with European trophies. In all of this time I experienced different emotions recording these goals. They ranged from exultation, taking me from a seated position into an occasional leap of triumph that came with the automatic appreciation of excellence. Then there were the others that burdened you with obvious disappointment but which had to be pronounced like you were devoid of partiality. Of course, I was accused of bias from time to time but accepted that as an inevitable part of speaking into a microphone to a sensitive Scottish public which often pulled no punches as adjudicators of football broadcasters. They were skilled at that.

So the goals that clung on to me are here to be read as evidence of a man lucky enough to have had pre-broadcasting memories that indicated how stirred I was by goal-scoring from well before puberty. It was embedded in my nature as I try to show initially here. And of how, eventually, a microphone turned into a magnet that attracted irreplaceable memories of certain balls nestling in nets that also uncannily reflected the ups and downs of an unpredictable football life.

1

The First Hurrah

Scotland v England

13 April 1946

1–0

Goal: Jimmy Delaney

TO ACKNOWLEDGE THE ending of the Second World War and the return to what might pass as normality, my father took me to a football match. Many others had the same idea. Indeed, I always look back with pride that I helped create a statistic that stands out like a testament to survival after the ravages that the Luftwaffe heaped upon my part of the world. For 138,468 were inside Hampden Park on that special day, 13 April 1946. The Scotland–England game had been advertised as a Victory International that proposed a sense of collective celebration and a unity that had brought us through the war together. Except as I climbed up the steep stairs of the east end of Hampden I could sense the tribal anticipation amongst the Scots of wishing to deprive the English of the mantle of invincibility that had been worn since they had defeated us in the last match before the war, 15 April 1939, 2–1 at this very stadium. And hadn’t they trounced us 6–1 in an ‘unofficial’ game in 1945 when we could hardly put a team together? This was the Auld Enemy no less. The bonding uniforms were out. Civvies were in.

So I was to view the Auld Enemy for the first time from a posture that was far from comfortable. I was wee. Everybody else was big. Then there was the squeeze half-way up that vast east terracing slope which was like being put alongside Hogmanay revellers in the last tram to Auchenshuggle. But help was on hand. In those days, small kids like me, would be passed over the heads of the crowds like ‘pass-the-parcel’, to comparative safety nearer the front, to the cries of, ‘Watch the wean!’ So, unknown to my mother I parted company with my father as I was transported over the heads of the crowd to just behind the perimeter wall from where I was to see a goal that lives with me to this day.

The players seemed gigantic to me down there, the English particularly so. They seemed like rough hooligans, bullying sergeant-majors, uncouth. Ours were cavaliers fighting a just cause. The blonde-haired Bobby Brown in the Scotland goal seem to exemplify for me the purity of their makeup as he gracefully pulled crosses out of the air despite the constant aggravation of the great England striker Tommy Lawton, the man they were to call ‘The Hammer of the Scots’, backed up as he was by talented midfield players Denis Compton and Len Shackleton. But the core of the Scottish defence, the two Shaw brothers and Frank Brennan at centre-half, all of whom came from the one small mining village in Lanarkshire, Annathill, never flinched.

Peering from the low position with no conception of time passing in the match but feeling growing frustration, the world suddenly exploded. There had only been two minutes of the game left in fact. Two great wingers who could cause an argument in an empty house about who was the superior, Willie Waddell of Rangers and Jimmy Delaney of Celtic, combined to convert 139,468 into a seething cauldron.

Jackie Husband takes a free kick. Waddell gets his head to a ball in the air, deflecting it into the path of Delaney who crashes it (as I can recollect) into the net. The game has been won, snatched from the deadening clutches of a no-scoring draw. In the madness around me I experience a personal feeling that I still think ranks with any sensuality I was ever to feel in adult life. But, from that moment, in a sense I never did grow up.

For that small Hampden boy was with me every time I raised a mike to my mouth with the Auld Enemy in sight. He was inside me, kicking every ball for Scotland as I tried to retain professional objectivity, although both of us nakedly desperate to relive another tumultuous Delaney moment.

2

Local Hero

Shettleston Juniors v Vale of Clyde

Late 1940s

Cup game (but which tournament I can’t really recall although being a kind of local derby it felt of global significance)

Goal: ‘Doc’ McManus

THE FIRST STOP after getting out of the cradle was Shettleston Juniors or the ‘Town’ as they were called. Now ludicrously renamed Glasgow United FC, thus deprived of its special identity. They wore the white shirts of neutrality in an area that was self-consciously sectarian and because of which much time was devoted to determining which foot you kicked with. ‘Doc’ McManus united both persuasions because he seemed to represent the honest endeavour of those men in dungarees who would come straight from their work on a Saturday, visit the bookie, have a snort in the pub and then to the game, bawling threats to certain players that they would have liked to have made at their gaffers the other six days of the week.

The Doc amused them, made them more genial for some reason. His appearance seemed to help, coming as he did from the tradition of Scottish junior football inside-forwards, owing a great deal to stunted growth, a fondness for the bevvy, a disdain of sprinting more than six-yards and a body-swerve in which the heavily endowed backside and torso seemed to part company for a fraction of a second.

But he could play. He had deft touches which belied his appearance and that made him distinctive, set him apart.

Came the day of the cup-tie. The Vale were a club that folk talked about in Shettleston as if they were toffs because their name suggested something sylvan as opposed to us who had only wally-closes to brag about. And they had won the Scottish Junior Cup in the past, something that was never to be paraded up Shettleston main street.

It was windy. And I recall the pitch, after days without rain, was blowing ‘stoor’ into my face where I used to stand low down next to the perimeter railing, because in comparison to being in one of the larger Glasgow stadiums, this was like being at the coal-face where you could actually hear the grunts, the screams, the tirades, the obscenities as men hewed away at each to get something out of a game. I look back on junior football with genuine affection even though I realise that the passing of time has its romanticising effect. And, of course, I only have sketchy memories of that particular game. Although, Doc McManus’s goal is in the mind as if it had been filmed and placed in my memory by Spielberg himself. It won the match after Shettleston had equalised a Vale lead and it came somewhere near the end of the game. The stats are shaky, the goal is not.

McManus was enduring the kind of game that was provoking some mirth among the Town support I recall. But they were tolerant of his lapses because as an eccentric, compared to his hardworking but mundane teammates he always carried the possibility of the unexpected even though at times he looked as threatening as the man who lined the pitch. The Town were playing towards the bottle-works end where many of the fans actually worked. Efforts were sailing over that bar as if the ball was volunteering to act as a plug for one of the bottles there. Then McManus struck.

The penalty area was packed and on the hard pitch the ball was frisky and awkwardly bouncing. It was about hip high when it came within his reach. As it fell he half-volleyed it. Yes, this rotund figure hit one of the most difficult of shots to control, as if he were of leonine stature, and the net obligingly stopped the ball from reaching the bottle-works. The game was won and the men behind me reacted as if the bookie had laid odds of 100–1 against him scoring at all.

I have no idea what the rest of life had in store for Doc. But although the name Shettleston Juniors is now defunct Doc is still an image that pops up occasionally to remind me of halcyon days when junior football seemed like one of the essential building blocks of nature.

3

Tribalism

Celtic v Rangers

3–1

League Cup

25 September 1948

Goal: Jackie Gallacher

PARTICULARLY ON SATURDAY nights a couple of us used to frequent the pavements in front of pubs along Shettleston Road to exploit the inebriated shapes that would emerge from the interiors, and fully aware of the basic good nature of Glasgow’s East Enders, inflated by copious amounts of booze, knew they would often slip us a few pence, given the ‘Buddy can you spare a dime’ look on our faces of the underprivileged. That naked exploitation had another dimension to it because we would also hear gossip from men who seemed to miss nothing that mattered in life. We would choose either a Rangers or Celtic pub depending on recent results to exploit the mood of the denizens and so picked up the special lingo of the opposing affections. ‘Which foot does he kick with?’ seemed to be a prime sociological query. At that short-trousered age the two names that we heard talked about almost with reverence were ‘Tully’ and ‘Thornton’. They were spoken of as disciples of contrasting faiths which we were never to take lightly. Thus, I consider myself fortunate enough to have seen them play against each other in a match at Celtic Park one clamorous day. I recall it also because I didn’t pay to get in to my first Old Firm match. I was lifted over the turnstile by a complete stranger. Yes, this actually could happen in those days when welfare did not seem to emerge from legislation but came from the goodness of the heart. So Charles Patrick Tully of Celtic and Willie Thornton of Rangers faced off against each other as specimens of Shettleston Road’s split affiliations that made life worth living for so many. But, frankly, it was Tully’s day. I had heard the chat about him like he had supernatural qualities as a player. The Belfast man I had only seen in photographs up till then looked more like the tousle-haired gasman who used to come to light up our tenement closes, and as menacing-looking as Bo Peep.

In Celtic Park that day though we learned a simple lesson for the growing-up process, that appearances can be deceptive. He glided through the game, audacity blending with skill. Upon such a balletic performance the Celtic recovery was based. For they were a goal down in only 11 mins from the foot of the high-scoring Willie Findlay of Rangers. Frequently Celtic teams in those times would wilt and succumb after such a set-back. But it was noticeable that, even then, they seemed to be having much of the play. And I do recall that stemmed principally because that tousled figure from Northern Ireland seemed to be everywhere. He was one of those players who the more he was able to slip past two or even three players could evoke admiration from his supporters although never really being in the hunt to score himself. Essentially that would not matter if he could prop up the others – which he did. He was the ultimate provider. In 39 minutes came the goal that changed the game and bolstered the Tully adulation. In a typical solo weaving movement he deceived a highly respected Rangers defence comprising of hardened players like George Young, ‘Tiger’ Shaw, Sammy Cox. Wrong footed and with a pass that his winger Johnny Paton accepted eagerly, that defence could not stop the ball being slipped to John Gallacher, in front of goal who had a relatively easy task of netting. 1–1.

Yes, Celtic would go on and score another two in their ultimate 3–1 victory. But that first goal, the equaliser, was a huge psychological boost for Celtic and I could sense it as a prelude to victory. For Rangers had never come across the likes of Tully before. The Glasgow Herald did not sell particularly well in my part of the world then. But those who did pick it up would have read this of that afternoon’s result, ‘The player who must take most of the blame or credit for that was Tully, undoubtedly the cleverest forward in the last 10 years of Scottish football.’ The Sunday Post which most people read for the pictorial ‘Broons’ page, wrote this of the game, ‘…no matter what the records may show, this must always be remembered as Tully’s match.’

Joe Mercer, who played against him as Arsenal’s captain in the Coronation Cup final of 1953 and lost, once said, ‘Who could forget Charlie? Marking him was an education.’ And having put two corner kicks directly into the net at Brockville in 1953, after the first one had been disallowed, added further to his legend. Willie Thornton? Great players have ‘off days’ and this was one of them. I did recollect him hitting the post on one occasion but no more than that. Although, our takings outside the Rangers pub swelled later in the year as they were to go on and win the treble, with Willie Thornton their top-scorer with 34. But it was that Tully-inspired goal which inescapably reminds me of the day I was lifted over a turnstile.

4

Starstruck

Real Madrid v Eintracht Frankfurt

7–3

European Cup Final

18 May 1960 Hampden Park

Goal: Alfredo Di Stéfano

RIGHTLY OR WRONGLY this was the evening that encouraged me to think I could at least write something about football. How could I become entranced with what I watched in that game without wishing to register something about such a spectacle? Of course, I only toyed with the notion, as many others might have done as well. This game I relate, perhaps fancifully, to brotherhood. Now you become a naturalised Scottish citizen after five years lawful residence in the country. Ferenc Puskás, born in Budapest 1 April 1927, and Alfredo Di Stéfano, born in Buenos Aires in 1926, achieved it in exactly 90 minutes at the National Stadium in front of 127,621 witnesses who initially embraced the entire Real team as if they were relatives. Nature had helped. On a brilliantly sunny evening their white shirts looked as if they had been laundered by the gods. Indeed, in the years following, the Real players would look fondly back and admit that it was their finest performance in a match that some would claim was the greatest final ever played at that ground. But uniquely we all experienced something new in the crowd. We were simply spellbound. My good friend and superb journalist Hugh McIlvanney was to write in the Observer of ‘the strong emotionalism that came over the crowd’. That was it. Although we were in awe of Real to an extent, because of their attempt to win this trophy for the fifth time in a row, the Germans had impressed us with the quality of their play in demolishing Rangers in the semi-finals, and actually scored first on the night. But, basically, at kick-off, there was no strong ‘home’ crowd sentiment for one or the other.

But there was contrast. Watching the Germans play before this game you could tell why the trains ran on time in their country. They were organised, strong and resolute. Real, on the other hand, offered the appearance of revellers who couldn’t tell what time of day it was and cared less, but had boundless compensatory skills that were unleashed that night after being angered at losing the first goal. Now Ferenc Puskás was the only man ever to score four goals in a European final, as he did that night, encouraging the belief that the game ‘belonged’ to him. It was shared. The two goalscorers soared above the rest.

Real were already two goals up through Di Stéfano when just on the half-time whistle the ball was picked up on the left side of the penalty area by Puskás who, with his left foot, from the narrowest of angles, drove it high into the net with such ferocity I felt the crowd around me were almost gasping. That was 3–1. It cemented itself in my mind that a man with a right foot only for standing on could be so lethal.

In the 73rd minute Di Stéfano, the number 9 prominently on his shirt, but playing in a ‘withdrawn’ striker role and thus greatly influencing play all over the field, was to score a goal that effectively killed off the Germans, for it came only 60 seconds after Eintracht had reduced the margin to 6–2. The Germans had only the briefest of time to congratulate themselves before the Argentine punished them for such impudence. For me it stands out above the rest because of its single-mindedness, its calculated act of retribution for the Germans having the gall to score at all.

For the centre is taken with hasty indignation. Di Stéfano begins a run out of the centre-circle, head over the ball, touches it to Puskás who slips it back. And on the edge of the penalty area the ball leaves his right foot. It is so low it looks like it could scarify the pitch and, as it makes the net, the static goalkeeper looks as if he had simply been blinded by brilliance. The ecstatic crowd react for the first time like they are the ‘home’ pack right behind Real. The fact that Eintracht pulled one back to make the final score 7–3 was merely a statistical irrelevance. For that night, we as Scots, ought to have been reminded of our heritage. For we had invented the ‘passing’ game and exported it around the world, particularly to South America. Real were now playing it with such elegance that it seemed so alien to our standards. So we poured out of Hampden on that gloriously sunny evening so dazzled by the brilliance of it all that we little realised that Scottish football could rightly claim to have set the world on the creative footballing path we had just witnessed. And as educators we could rightly claim Alfredo Di Stéfano as one of our honorary graduates.

5

Pars for the Course

Scottish Cup Final Replay

26 April 1961

Celtic 0 v Dunfermline 2

Goal: Charlie Dickson

I WAS ATTRACTED to this game because I had started to write reports on football matches like a kind of hobby set apart from teaching the rudiments of the English language to kids, and admittedly with an arrogance that stemmed from disliking some of the reflections I was reading in the main Scottish newspapers at the time. And this game was a replay, with all of the intrigue associated with a provincial club, the ‘Pars’, taking on the favourites. It turned out to be something special. I definitely recall the word ‘siege’ being written in my unpublished account of the game. But, paradoxically, it was many years later in San Francisco in 1982 that I learned more about that renowned Celtic siege which had lent distinction to this final. I was enroute to New Zealand with the Scotland manager Jock Stein to assess our opposition in the forthcoming World Cup in Spain. We were met by a Celtic supporter who adored the former Celtic manager and had learned we were in town and offered to take us to see the renowned sights. In a café within sight of the Golden Gate Bridge he asked Stein a direct question. ‘How did you feel about beating the club you loved in that final when you were in charge at Dunfermline?’ To which a bemused Stein replied, ‘I would have felt worse if I had lost!’ Which was a kinder way of saying, ‘I was always in this business to win things. For God’s sake, what else is there?’ And then he went on to talk about one man, Eddie Connachan. He was the Dunfermline goalkeeper on that rain-sodden pitch when the ball was like the proverbial bar of wet-soap. The Fifers had gone one up against the run of play in the second half when in the 67th minute Dave Thomson bent low to head a cross from the left by George Peebles past Frank Haffey in the Celtic goal.

Then followed the siege. Celtic armed with men like Paddy Crerand, Willie Fernie, John Hughes, Stevie Chalmers were barely ever out of the Dunfermline half. In circumstances like these the media along with the vast majority in the 87,866 crowd felt the equaliser was inevitable. However, those of us who were there can still recall the amazing series of saves that Connachan made that day. He was an ex-miner like the Dunfermline manager himself and that might have created a special affinity, for by and large Stein was allergic to goalkeepers throughout his career as they seemed to bring rushes of contrasting emotions to his head. That day Connachan stood up to the battering like he was facing a dam bursting. He threw himself around the goal-line, he clutched, he palmed, he tipped, he smothered, and in one particular instance he miraculously blocked a 25-yard Crerand shot through a ruck of players that had looked bound for the net.

William Shakespeare in penning his plays would, to great effect, use a device called tragicomedy. He would have been in his element that day in describing the ending which evoked tears and laughter all in the one, depending on your point of view. It is what made the goal so memorable. A long innocuous ball is played towards the Celtic goal in the 88th minute. It was straightforwardly a goalkeeper’s ball. Except it wasn’t. Frank Haffey was in the Celtic goal. He fumbled the ball, and when it dropped to his feet, for some unaccountable reason he seemed to walk past it like it was contaminated. Charlie Dickson, an honest-to-God kind of striker was left to walk the ball into the empty net adopting the casual demeanour of an owner escorting his dog for a pee. 2–0. Close to time up, some disillusioned Celtic supporters vented their fury at the outcome by throwing bottles aimlessly but dangerously into space. My researcher Pat Woods and father at the bottom of the terracing were paralysed by the terror of it all. Dunfermline had won the 76th final in their 76th year.

A man in a white coat rushed on to the field to hug his players with a special embrace. It was Stein. I now recall that manoeuvre as merely a dress-rehearsal for other triumphs to come, and of which my reports of such would then be in the public domain.

6

Auditioning

Celtic v Rangers

0–1

Scottish First Division

8 September 1962

Goal: Willie Henderson

IT WAS WRITING a short story for the BBC which had nothing to do with football that introduced me to sports broadcasting. Liking what they heard of my reading it on the air they asked me if I would be interested in reporting on football. However, they would have to audition me and could I pick a game and come back in so they could listen to how I could cope with such reporting? I chose the Old Firm game. There was also Shettleston Juniors versus the Bens I could have provided for their delectation, and how I could cleverly make a silk-purse out of a pig’s ear, sort of thing. But this was an audition I was heading for, and doesn’t an Old Firm match speak for itself? Yes, in crude terms admittedly, and with unique choral accompaniments, but it would be all too easy. The game would do the job for me.

I got more than I had bargained for. Would they allow me to exceed the two minutes they asked for? Like, half an hour? I would have needed it.

Firstly, how do you describe being part of a crowd of 72,000 rooted in visceral hatred. Would I need to reflect on that in some way and make some philosophical reference to knee-deep sectarianism? But, this was the BBC I was auditioning for, who certainly at that time had nothing more provocative on the air than the blessed voice of Kathleen Garscadden introducing Children’s Hour. Play safe, was my uppermost thought. Although, the crowd itself gave me another story because 19 fans were injured that day when they stormed the Janefield Street entrance in their anxiety to gain entry before kick-off. Another two ended up in hospital having ribs crushed against a barrier inside the ground.

The two incidents which made my biro skid along the surface of the notebook and put me in Hemingway mode, was, of course, the goal. And certainly the penalty award. It came on the half-hour after inconclusive and reasonably balanced play. Paddy Crerand in midfield for Celtic and frustrated by the inept play in front of him, strode into Rangers penalty area, where he was clearly tripped by Ralph Brand. The penalty awarded was incontestable. But the Rangers players began to complain about how Crerand was placing the ball on the spot, apparently generously, to his advantage and kept pestering him about it until he lost the rag and threw the ball at his opponents as if offering them to spot it. After that furore it was no surprise that Ritchie in goal saved his eventual shot.

Such an event, unsurprisingly, gives enormous boost to one obvious side and although Celtic had much of the play in the second half, they never really convinced me they were going to score, and definitely Rangers looked the more dangerous on the counter. Then it came. Willie Henderson was a figure the Ibrox fans held in high regard. Small, wiry, tricky and with excellent judgement of pace he had been quietish but still potentially threatening until near seven minutes from the end. For some reason he had switched to the unaccustomed left-wing of Rangers attack and in one thrust beat Duncan MacKay at right-back, made towards goal and shot. Now, my recollection is that it was not a cannonball Haffey had to deal with but merely let it slip through his grasp, and although defender Kennedy tried to stop its gentle roll towards the line he could only succeed in helping it on his way. The winner. 1–0. I was so pleased to have a goal to describe I decorated it with language fit for a World Cup final. At the end of the audition the anonymous BBC man said, ‘We’ll let you know!’

7

In at the Death

Third Lanark v Hibernian

1–4

Scottish First Division

Cathkin Park

3 November 1962

Goal: Jim Scott

THE BBC SET me free to do my first ever television commentary that day. I was too nervous to have any great expectations but I was travelling to a stadium that I greatly loved. When I was a boy my grandfather would take me on a long bus trip nearly every Saturday from the other side of Glasgow to see the Hi-Hi at Cathkin, because he thought Jimmy Mason, their dapper inside-forward, who was part of our conquering post-war Wembley side at Wembley on April 9 1949 and scored the opening goal in our 3–1 victory, was the greatest player on the planet. Mason was on my mind as I climbed onto a television platform for the first time, at the top of their long sloping terracing opposite their stand, for Thirds were on a slippy financial slope at the time and it was difficult to relate quality such as Mason to a club whom many thought were doomed. They had an owner in Bill Hiddleston who turned out to have run this respected institution in the south-side of the city like a speakeasy in south-side Chicago. He was a fraudster with astonishing nerve.

So rumours abounded about financial problems for the home club as Thirds and Hibs took to the field and my mike felt like I was lifting the weighty Stone of Destiny.

You could not see the Hibs jerseys without thinking of their Famous Five, and football people from the east in particular kept their memory rightfully alive. History, though, can sometimes weigh contemporary players down in the constant refrains that can be heard about the past records and any subsequent Hibs side simply had to live with that paradoxical factor. But, thankfully for the Hibs supporters, later that night, they had a glimpse of their great past. For on the film shown on Sportsreel (as our programme was entitled then), they heard me for the first time, as I raised the decibels by describing a goal that any Hibs player of any generation would have considered one of the best.

The odd aspect is that Thirds seemed the better side for much of the game but even in my rookie state I never felt they could capitalise on their midfield superiority. Then came the moment a goal was scored that made me feel I had arrived as a commentator. So, unsurprisingly, I gave it, as we would say in the trade, ‘laldy’.

Jim Scott finds the ball at his feet close to the centre-circle and takes off as if he has decided that any useful help was not going to be forthcoming. Now I can’t recall how many men he swayed and tricked past. Perhaps, three or four. By the time he had completed his mini-tour of the pitch all he had remaining to do was the easy part. He slipped it past the keeper nonchalantly. His big brother Alex Scott who was still playing for Rangers at the time would have been envious of one of the goals of the year. Despite that clear win, Hibs were only able to finish in 16th place in the league by the end of the season.

What I could not have known at the time was that it would be the last time I commentated at Cathkin. And that I had a goal to treasure that would always remind me of a great ground. It effectively closed down after Drew Busby scored their last ever goal in their heavy 5–1 defeat against Dumbarton at Boghead on Friday 28 April 1967. The Scott goal though was the first that put my exaggerated voice into the public domain which on reflection must have sounded like a hammy actor trying to recite Shakespeare. That’s how it felt as I walked away from a commentating platform for the first time. But I had at least laid my voice down there before they had put up the shutters on treasured space that I had always associated with growing pains and highly expectant bus-trips around the city.

8

Nobody Does It Better

England v Scotland

1–2

Home International

6 April 1963

Goal: Jim Baxter

IT WAS NOTICEABLE that Jim Baxter only put water to his lips as he and his partner sat beside my wife and I at the Variety Club Ball in Glasgow in the winter of 2000. We had been warned in advance that he was a ‘changed man’ by several people. Nevertheless, that did not prepare us for encountering a mere husk of the man I had known in the previous years when he could make a football seem like a serf in his continual acts of mesmeric control of opponents. Of course like many others we had known of his reputation for putting away booze with the same kind of determination that took Edmund Hillary to the top of Everest. And now he was paying the price for lavish self-indulgence having had to end his career at the age of 31. So in terms of conversation I felt like I was handling a delicate piece of porcelain and that by saying the wrong word I might end up with fragments on my hands.

I took the safe route by reminding him of the first time I saw him in a Scotland jersey when I was a fledgling broadcaster. It was Wembley in 1963, in front of a crowd of 98,606. Although I had little to do that day in radio I admitted to him that I was nevertheless suffering a little from stage fright and that what he achieved that afternoon was like turning my frayed nerves into sinews of steel. I could see that he was interested because I had picked, unwittingly, a game that he believed had been overshadowed